Ted Newell's Blog, page 3

May 2, 2014

Big theologians predict hard future for congregational churches

Caught my eye when Al Mohler, head of the rather right wing Southern Baptist seminary in Louisville, KY, talked to Episcopalian or mainstream evangelical but separatist (Amish, Mennonite inclined) theologian Stanley Hauerwas this week. Wouldn’t have thought they could be polite. But they are! Being face to face does good things. Here is a snip from the conversation. Sorry if it’s a bit technical sounding.

Mohler: ..when liberals made the Christian faith rational, they made the Christian faith irrelevant and unnecessary.

Hauerwas: Right. Well, I want to be careful with that word rational because I think nothing is more rational than Christian Orthodoxy. I think the Nicaea account of Trinity is an extraordinary development that is a tradition thinking through its fundamental commitment in a manner that is intellectually compelling. So the rationality that I was criticizing was the kind of rationalizing that presupposed that there was some kind of reason that didn’t reflect a tradition-determined mode of investigation. So I want to say that the problem with the response to the Enlightenment was it accepted the Enlightenment’s account of reason as reasonable, which was a deep mistake.

Mohler: Well, I appreciate that clarification because I certainly emphatically agree that there is nothing more rational than Christian Orthodoxy in terms of the right exercise of reason. But the attempt to make Christianity rational in Enlightenment terms with the autonomous reason, I just have to say, I think you make that point very compellingly, and it leads me to wonder sometimes if evangelicals aren’t methodologically sometimes following the same kind of trajectory that the mainline Protestants did, but just a century late. You know, perhaps many evangelicals are arriving at a new form of liberalism just about a century late.

My editorial: When a congregation operates out there as one little branch of a tree, no, as a branch that thinks of itself as an island of right thinking — as we all do in congregationally-governed churches with weak denominations — the way we know right and wrong is just what we think the Bible tells us, directly, personally. We don’t let the experience of 2000 years (AD) plus 2000 years (BC) correct our thinking. We won’t be subject to all that. But the price of that island mentality is that what seems right at the time can be confirmed as right, very easily, by a congregational vote.

H says that when Christians took Enlightenment reason as more or less right, they made a mistake. Of course! Enlightenment thinking is scientific thinking that imagines it is timeless, always true, not dependent on any assumptions. Cornelius Van Til’s big mission in apologetics was nothing other than saying, you have to ask about the assumptions. If you don’t surface the presuppositions you talk around in circles for ever. There will always be one more objection to your supposedly iron-clad “evidence.” Because evidence only counts in a tradition, a story, a worldview. Supposedly neutral evidence is not convincing in a Christian confessional worldview, perhaps, and vice-versa. (Of course lots more can be said here.)

So: In view of the way that we all tend to think the way the rest of the world thinks, the way most of us are schooled to think, congregational and orthodox minded churches need resources to help them (us) think more in line with historic Christianity.

All this to say: H says that the free-form evangelical church has weak grounding. Congregational, orthodox-minded churches could change rapidly to look more or less like our sainted predecessors. Think how the mainstream evangelical denominations of 1880 or 1890 looked by 1930. Wow. This interview is coded and takes some working away to see it, but wow.

Here’s the whole thing: http://www.albertmohler.com/?p=31352

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: Al Mohler, Christian faith, Christian Orthodoxy, Stanley Hauerwas

July 28, 2013

Agony, and Confidence

Man and son at the Wailing Wall, remains of Second Temple, Jerusalem. Courtesy Robert Chroma by Creative Commons licence.

Romans 9-11 is my nominee for The Most Difficult Passage in either Hebrew Bible or Greek Testament. Take a look at this opening.

“This is the truth and I am speaking in Christ, without pretence, as my conscience testifies for me in the Holy Spirit; there is great sorrow and unremitting agony in my heart: I could pray that I myself might be accursed and cut off from Christ, if this could benefit the brothers who are my own flesh and blood. They are Israelites; it was they who were adopted as children, the glory was theirs and the covenants; to them were given the Law and the worship of God and the promises.

Paul loves his own people dearly. He are one! Jesus also is Jewish, of course. I struggle with the idea that the NT can be anti Jewish, or anti Semitic when racially the supposed culprits are exactly that. Do they hate themselves, then? How could they, in a majority Jewish culture or even in a confident diaspora?

Paul goes on to say what seems clear to me — regular enough reader of Augustine — that God has his own internal “election,” that is, his own internal choice, and if you are in it, you receive mercy. God gives mercy to whom he chooses. Simple. Too simple:

“So it is not a matter of what any person wants or what any person does, but only of God having mercy.Scripture says to Pharaoh: I raised you up for this reason, to display my power in you and to have my name talked of throughout the world.”

Kolakowski the philosopher has a book entitled, “God owes us nothing.” The book is about Pascal’s group of Augustinian Catholics (Jansenists) who said just that, God owes humanity nothing.

The point is that collectively humanity has no claim on God. Our first parents forfeited God’s kindness. His descendants all ratify that stance individually, without exception — well, one exception, which is the God-man Jesus Christ. Those who belong to Christ regain the favor of God through the Beloved. Sounds good. But what to make of Pharaoh’s fatal appointed destiny?

Romans 9-11 has been discussed by far more able minds than mine. Let me say so up front. Barth the Swiss theologian has an interesting take. Calvin’s take is known at a folk level as reprehensible. Arminius, a Calvinistic Dutch theologian, could not stomach Calvin and came up with his semi-version, sort of God, sort of your human choice. But let’s bypass the polemic. Let’s go back to Augustine who had double predestination — in spades. Augustine said God chooses some for salvation and some for damnation. God elects, and God disposes! Never mind John Calvin versus Jacob Arminius, circa 1600s. From the beginning of the Western Christian tradition!

Note a deep mystery here. Scripture Old or New nowhere forces a choice between God or humanity making things happen. Humans do wrong and they act accountably. They act against the light of nature. They murder, choose war, practice idolatry or adultery, go in for witchcraft or drug-taking. The choices are wrong. In some sense the choosers could have done other, and should have done other. God did not sin. He did not force sin. He may have allowed the situation to be set up: that is why Christians pray, Lead us not into temptation. If God puts me in a hard place I may fail, and God have mercy and help me. If I do sin, I did it. Not the Devil. Not God. Not my mom. Me. (Psalm 51)

Paul writing about his own race, not about individuals, concludes that God will surely have mercy at the end — see Romans 11. God promised mercy to Israel and he will surely deliver.

Within Israel, not all individuals of Israel are elect — some are his people, some are not. Being circumcised, or baptised, will not place you in or out by itself. God knows the individuals who are his (2Tim). He made them alive. He made them alert. He worked through their life circumstances to bring them to himself.

“Long my imprisoned spirit lay/Fast bound in chains and nature’s night/Thine eye diffused a quickening ray/I woke, the dungeon flamed with light/My chains fell off, my heart was free/I rose, went forth and followed thee.” (C. Wesley’s famous hymn, “And Can It Be.”)

Romans 9-11 reminded me of two things.

(1) Those who focus on the details of whether BC believers, who never heard, are in or out, are focussing in the wrong area. The big picture is that there are damned (Pharoah) and there are elect. The fzzzzy middle is not the place for focus; rather look at the massive ends of God’s people and non-Gods-people. As offensive as salvation of some not all is, the fact that the Son of God was predestined to die affirms the seriousness of the issue. I had a Book of Revelation moment as I read. I was renewed in my understanding of the seriousness of life and death and God’s amazing intervention.

(2) The second reminder is the urgency of prayer. God moves, and no one can stop his hand. God does not move, and nothing can stop our decline. “Our” can include apparent Christians, also our society, also the world. Prayer is the space God has made for changing world history. No accident that at the cracking of the seventh seal “there was silence in heaven for about half an hour. Next I saw seven trumpets being given to the seven angels who stand in the presence of God. Another angel, who had a golden censer, came and stood at the altar. A large quantity of incense was given to him to offer with the prayers of all the saints on the golden altar that stood in front of the throne; and so from the angel’s hand the smoke of the incense went up in the presence of God and with it the prayers of the saints” (Revelation 8). The prayers of God’s people make a hinge of history. What an encouragement to be about God’s gracious work.

As a footnote, I had a great supper last month with a Serbian Orthodox nonbeliever who told me the difference between Serbs and Croats, that is, Slav Orthodox Christians and Slav Catholic Christians (same race, different theologies). The Orthodox say, Ah, don’t worry, Jesus took care of it. The Catholics say, We better stay clean. Jesus took care of it but we better do right. The Croats are more rigorous. Maybe the Orthodox are onto something; maybe they “get” the cosmic effects of the death of the Son of God. On the other hand, er, isn’t there supposed to be some life change if you really “get” it? The Bible looks for “fruit.” But the issue we did over supper is the issue we are talking about here. God chooses. God disposes. God hears prayer.

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: Apostle Paul, Augustine, Bible, Christian life, civilization, culture, gospel, history, Jesus Christ, New Testament, prayer, predestination, responsibility, Romans 10, Romans 11, Romans 9

July 13, 2013

What is a “good” pastor? What is pastoral leadership about?

Here’s a short, short, story. In the later 1980’s I was a small cog in a big corporation. I was a District Manager for the inventory-financing arm of an insurance corporation. Though customer happiness was an aim, the job was to maintain the corporation’s financial security. We (three) twenty-somethings were watchmen, and had credit authority at a non-dangerous level.

At Branch Manager level and up – beyond us – one got ahead by paying attention to routines of management and by influencing others. A manager could rely on numbers to assess good and weak employees. To assess the value of our branch, head office used financial statements. Eventually, head office decided that functions except risk management could be done best from the central office. The local processing staff, whose work did not pay the company well enough, was let go.

A single executive can manage a huge corporation easily because all employees follow a shared culture. Managers watch employee performances on any number of criteria – daily, weekly, yearly as appropriate. They alter performances by interventions based on numbers. But don’t miss this: Employees know that they must “produce.” All corporate for-profit cultures demand it. Good people produce. Performance is being tracked. The corporate theory of human nature supports it. The results can be sweet V.P. or higher, or they can be dire. The key factor in managing a company is the utilitarian code.

Shared culture is how capitalism works. Capitalism depends on assumed infinite resources, processed by most efficient methods, for output of maximum goods and services. The global reach of capitalism has carried the “modern” mindset – especially utilitarianism applied to people – to the ends of the earth. Any person who shares the utility-maximizing mindset has the primary qualification to work in the office of a multinational in Mumbai, India, or in Canada, or wherever. Capitalism, one of the two major ideologies of human material progress (socialism being the other one; see e.g. author Goudzwaard), is a time- and money-maximizing system.

In a church, however, producing criteria do not apply. Production criteria would be ungodly. No human being can accept personal responsibility for the faith of another person. You cannot program spiritual growth in others as a computer is programmed.

But producing criteria can be made to apply.

Story Two: An executive pastor of a large (“mega”) church talks about how to manage a church staff. Pastors on staff were to be managed by mutually agreed external, verifiable, goals. Staff pastors were accountable to agreed external goals at the risk of their jobs (my typo was goads).

Story Three: A pastor went on the staff of a church-growth minded local church. His performance targets were set at a special meeting, not with the senior pastor but with the senior administrator. The administrator lacked theological background. The question was no longer whether the assistant pastor prompts faith – no longer his role!

Theology is marginal in the now-routinized churches of Stories Two and Three – as, it seems, is faith. In utility church thinking, current adherents have become the means to production of a larger congregation. If you step forward to lead a small group, you are helping the cause; you have become a means to the end. What is wrong with that? Nothing, except that members can begin to feel that they are valued not as persons but as (unpaid) employees. You might have been manipulated into serving. No matter. The end is being served and the end is justified as overwhelmingly valuable.

If some members begin to feel that the thing is a machine, they would be correct.

Is church growth other than a way of rationalizing the life of a body of believers? Is it more than application of utilitarian principles to church life?

This method of operation is Leadership Magazine incarnated. Leadership Magazine knows nothing of special theological commitments. A leader in any church can read Leadership Magazine, as can leaders in a synagogue, a mosque, or Mormons, or Jehovah’s Witnesses. Possibly even a Buddhist sangha might benefit. (Why not.)

The insight of this piece is this: In assessing any pastor, the nature of the church becomes the crucial question.

What is valued as good pastoral leadership depends on a church’s self-understanding and her context – at least to some extent.

For examples:

For a utility-maximizing church, seeking a pastor means seeking a rationalizer, an effective manager.

The pastor in some South American settings would be expected to have planted six or more sister churches. In a setting of relatively easy evangelism – of fields white to harvest – this is a reasonable requirement. Mandatory evangelism applied to North American church leaders after four centuries of Christianity – less reasonable. A pastor who plants one church in a lifetime has an achievement worth noting.

Under persecution such as in Pakistan, insisting that the pastor generate church growth is laughable. Merely maintaining a witness in such conditions is paramount.

Maintaining the faith is paramount also in France, where the secular landscape renders historically-orthodox Christianity nearly invisible.

In a mainstream church dominated by the progressive-liberal mindset, a pastor active in social redemption ministries or initiatives might be highly prized.

In Catholic circles, anyone qualified to administer sacraments is sought after.

In Anglican circles with inactive homes in a majority, an ability to activate passive members and families by parish missions would be appealing. Alternatively, for liberal-progressive minded congregations again, a social worker, might be appealing.

Does “good” pastoral leadership depend on the church’s self-understanding and context?

Can there be a middle ground between making sure the nursery is well-staffed, and building up the faith of the faithful? Open to hear.

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: assessment, church growth, Donald McGavran, economics, evaluation, local church, market, marketing, mission, missional, missionary, pastor, philosophy, practical theology, strategy, theology, utilitarianism

July 11, 2013

What Could This Church Leader Do?

Case learning about church leadership can help deacons, elders, or seminarians, to develop a strategic ministry mindset. Many boards want to initiate a phase of imagining their church’s future – by looking into identity, by wondering about ministry priorities, or even in the process of searching for a pastor.

The case below is inspired by a seminary experience. As part of seminary training, I attended a church not of my denomination for a semester. With a partner, I turned in a report to both pastor and professor. As one of a series of presentations, we presented the report as part of “Introduction to Pastoral Ministry.” The pastor came and talked to the class about the church’s potential. The presentations enabled seminarians to think about pastoral strategies in a variety of settings, with varying congregational compositions, sociological constraints, and, not least, theological beliefs.

Church leaders need to think about issues facing churches, to see contexts and the nature of pastoral leadership. To develop a strategic mind, case studies as used in management training will be as helpful as presentations of church visits. In discussions of case problems, seminarians, deacons, and elders can learn to think through church problems and issues together by close examination of real-life snapshots. They learn to think of churches as having varying potentials constrained by their social setting, appealing to a certain sociological grouping of possible attenders, etc.

This case, and others to follow, asks you to consider: What is possible for a pastoral agent in this setting? How could a board be creative in this church/social setting? This case is a draft, and if interest develops, it could be one of a series of at least five cases that a board or seminary class could consider together to build understanding of church strategy.

Case 1: Building Bridges of Hope

Phase I

John was the 38-year-old solo pastor of Jared Evangelical Church, a rural congregation in a less-developed but deeply traditional area in North America. The church included 120 adherents, mainly middle-aged or older, few young adults, a dozen or more children. Sixty to eighty persons attended on any given Sunday morning. Young people tended to leave the area for work opportunities, and church attenders were those who had stayed and loved the area. The economic base had not developed in the two centuries that the area was settled. Agriculture remained the direct or indirect source of livelihoods, and pensions were an even larger source. Members tended to be related to other members. With the completion of a new highway, however, people not born in the area were buying property and moving in. The new residents were visible at farmer’s markets and community socials. Though they tended to remain in their work and social circles, as often as not they had children or teens who attended the local all-grades school and who might be directed toward church programming.

Potential new attenders and members of the church were in a ten-kilometer (six mile) half-circle, bounded by a wide river on the west and extending inland. The potential field had a population of 13,000 persons in the early 2000’s, including active and inactive adherents of three other churches. Active church participants who attended at least one time per month, including children, totaled about 2,000 persons. The potential field also included non-attenders for whom any church – especially a long-established church like Jared – was loaded with historical meanings and significances, either unfortunate experiences of disruption with a relative or friend in a past generation or just a negative association with the sometimes rigid Christians of years past.

Jared Church was the first church to which John had given leadership after five years as minister for church education at a medium-sized city church. The city church had members who were evangelical or soft charismatic as well as liberal. At Jared Church, John enjoyed a supportive group of deacons who looked to him for guidance and initiatives and to whom John listened carefully in their monthly meetings. The deacons were four middle-aged family men – sons of the area – plus a retired banker who had passed his career in another province. Church programming was not extensive – perhaps a little less than a neighboring church of the same denomination. However, it included a Sunday morning child-care scheme; Sunday School; a Junior Church program for young children during the service; a midweek program for youth that ran during the school year; and a week-long Vacation Bible School. The church always represented itself in frequent community fundraisers for a neighbor’s illness or anniversary. In times past, when more vacationers attended, the church hosted an outdoor Sunday evangelistic service.

John had been the pastor for three good years. Attenders disaffected after a previous pastorate had returned. Much of his time still went to house visits, plus organization for Sunday morning worship, regular hospital visitation in a distant city, and a midweek prayer-study meeting. Now, from two to five visiting worshippers could be expected on any Sunday.

As John sat down to plan for the next year, what should he be considering?

Would this church be able to welcome all newco?

Phase II

In his previous pastoral experience John had developed resistance to church growth approaches. These approaches generally emphasized removing roadblocks to church attendance such as inadequate nursery facilities. They boosted community contacts. However, they said relatively little about the beliefs of the faith. John took two deacons to a Sonlife seminar at the two-year mark. The seminar first advocated deep discipleship and then, in a sudden move, equated deep discipleship with evangelism, especially having members work together to fill the pews. John was disappointed. He looked around for other approaches and was also unhappy with Christian Schwartz’s Natural Church Development. NCD was based on empirical assessment of a dozen key aspects of church life, so that churches could try to improve their lowest performing aspects. John knew that value assessments underlie all charts full of numbers. Why did Mr. Schwartz think the churches of the empirical study that founded NCD were healthy? The church John had served as associate was written up nationally for its ministry effectiveness, yet a survey of church members which formed part of the research, available to pastoral staff, told him that 47% of attenders disagreed or were not sure that Jesus is the only way to God. It seemed that theological (or Christological) beliefs are separate from church effectiveness to some analysts. But could a church be called “effective” if the manifestations were disconnected from their shared faith? Would active social work warrant the label “effective”? Lively worship? Being a welcoming congregation? Similar criteria could be applied to a variety of social groups. A church’s life must show the virtues of its beliefs, John thought.

After some digging, John found a program from a group in England called “Building Bridges of Hope.” “BBH” looked for church renewal and effectiveness but did not ignore the theological or faith of the churches. For implementation, BBH required a partnership with a church of another denomination. A team from each partnering church would visit, observe, and report on the other’s church. With fresh eyes, the team would take into account the kind of church they were visiting; if visiting a Pentecostal church, then distinctives of Pentecostalism would be factored into their assessment and recommendations. If Anglican, the same sensitivity would come into play. John does not remember if he presented the BBH method and his intentions to the deacons.

As a way to launch a vision-casting phase early in his third year, John arranged for a denominational leader to lead a generic vision-casting workshop on a Saturday morning. The workshop asked general questions and raised awareness of the future of a church that were not connected to BBH specifically. John needed attenders and members to attend so that a genuine sense of need would propel vision-casting phase in the new year. From the pulpit, he asked all members and attenders to make the particular Saturday morning a high priority. He placed the snappy graphic of “BBH” in the bulletin – especially appropriate because the church was located next to a huge new bridge over a wide river. The bridge had been in construction all the time John pastored there and was then nearing completion.

On the day, only the long-term members of the church appeared, with no exception. John felt he had failed. He was so discouraged that further initiatives were held in abeyance until assessment could be made. John left the church eighteen months later, and new leadership pursued new priorities.

Possibly no one else knew how much John believed was riding on the initiative. No area minister or friend coached John in the lead-up or debriefed me him on the failure. It is striking that in the ten years since that initiative, John has never thought about what went wrong – other than that he should have phoned and buttonholed attenders and members more persistently.

Can you suggest advantages and disadvantages of any “packaged” approach to church development such as NCD, Sonlife, or BBH?

Do you agree that theology needs to be connected to church effectiveness?

Is “growing” always a sign of a church doing what a church should do? From what you read here, is Jared Church living out the Good News as well as it can?

Is the Good News sufficient for a church to grow?

Why did John think he had failed? Were any oversights due to lack of experience? What could he have done to resume the visioning process?

Were board members able to see what was going on, do you think?

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: case study, church leadership, deacon, elder, minister, missional church, pastor, practical theology

July 10, 2013

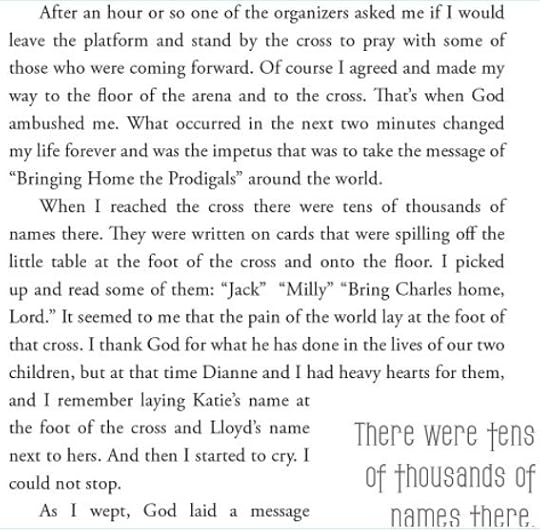

Rob Parsons and the prodigals

Rob is a lawyer, organization starter, and church leader in the UK. What he describes started a series of conference centre events at which 50,000 people came to pray for their very varied prodigals.

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: elder brother, family, father, mother, parenting, prayer, prodigals

July 1, 2013

Can Christian faith stand up to intense unfair suffering?

I’ve been writing an article about the human tendency to suppress uncomfortable truth, and how that suppression affects teaching situations.

Shoshana Felman wrote two decades ago that two aspects mark every educational situation: things we want to know, and that which we absolutely cannot let ourselves know.

As research, I watched the nine-and-a-half hours of Claude Lanzmann’s Holocaust film.

This blog entry is me trying to figure out how God could be fair.

The film centers on interviews with survivors and perpetrators of the Polish Nazi 1942-45 death camps, with contemporary on-site footage. The viewer is led to imagine the scenes that the witnesses describe.

Lanzmann’s Shoah is definitely not a mini-series. The filmmaker gives one break at the half-way mark. No photographs or 1940s film footage appears. Shoah is all testimony.

Holocaust deniers point out that the film’s philosophy allows that strictly literal truth is not its only concern.

Myself, I found the testimony compelling from beginning to end.

Self-deception by culprits to bystanders – even most victims – is in the film in every nook and cranny.

Then I went ahead and read Isaac Bashevis Singer’s novel, Shadows on the Hudson.

Singer tells the story of the grown children of Eastern European Hasidic Jews who are somehow in America.

Their strictly-observant mothers, fathers, siblings, cousins, grandparents, were reduced to ash by the Nazi murderers.

Can the children still believe in their parents’ God?

How can the God of Abraham be worshipped with integrity?

In dramatic form, Singer’s book does the metaphysics. Five-hundred-plus page-turner pages work out the possible character of God in the lives of the characters.

.

Why is America and Europe fascinated by the Holocaust? After all, there is a Holocaust industry.

What accounts for the Holocaust’s continuing reception by media outlets and in the public?

How weird was the Holocaust really?

Is German racism more or less horrific than Rwandan racism or Serbian racism? Is it the cruelty of Nazis who play with infant skulls? Is it the Nazi practice of having fathers dig graves for their families? Shooting one in three in a lineup?

What happened in the Holocaust has happened since.

In Europe, Serbs, Croats and Romanians outdid German cruelty in the same period – check it out.

Westerners expect African and Balkan barbarity.

Is it a reverse racism that advanced white European Germans should never have been capable of such viciousness?

They were so advanced: Look at their Goethe, Beethoven, Schiller.

As Singer’s characters say, there have been Nazis since forever. Look at Genghis Khan.

Is the Holocaust fascinating because the modern German industrial approach made huge-scale killing possible?

Left-wing progressives planned and carried out catastrophes. In China, Russia, Cambodia – and not against others, but against their own people who thought or lived in “non-revolutionary” ways.

Any of us discover irrationality in ourselves at the highest level of refinement. Ask Woody Allen.

But recognizing that any human is a potential barbarian does not vindicate God.

Could a good God allow horrors to happen?

Maybe, as Singer’s characters sometimes say, he allowed human free will and this means the possibility of catastrophes.

The Hebrew Bible already shows the faithful recognizing, “We were like sheep to be slaughtered.”

There is no shortage of Hebrew psalms anticipating or working through some horror or other.

“Sing us the songs of Zion,” say the Babylonian captors, against the backdrop of a God who has ripped his people from the land of promise.

Yet monotheism means that the one true God controls time and space.

In the final analysis, he at least allows all that happens.

If God is good, could he allow a Holocaust horror?

Maybe he is not good. Maybe he is not all-powerful.

Apologists could reply that life on Earth is nowhere near as bad as it could be. Human life is sustained all the time and we are mostly unaware. Disasters are aberrations.

I flew onto a runway recently. The plane made it from 35,000 feet at 600 miles an hour, with all tires intact. A miracle! To one passenger, anyway.

That there might be even more disasters is an abstract thought, not gripping.

A Holocaust is big enough to raise the question about God.

The walking dead of Singer’s books and short stories must have it right.

Post-Shoah, his characters cannot without such a god, and cannot live with him either.

If God is good, could he allow a Holocaust horror?

If an irrational, unbelievable, literally incredible return to a traditional Judaism is impossible for Singer’s characters, the answer must be a flat “No.”

The Holocaust was so massive and so vicious that the only right response seems to be silence.

The injustice to his own people does in worship of a god uninvolved in such suffering.

Without a God who enters into suffering – somehow – his chosen people bear the pain.

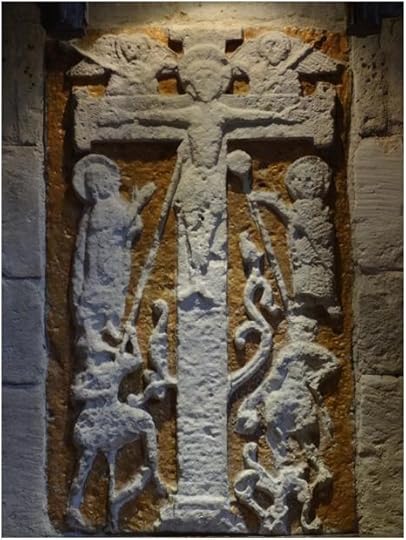

Does a crucified Son of God somehow vindicate God’s silence?

Isn’t the resurrection –a space-time historical event – God’s once-and-for-all hopeful answer?

The skeptic says that the Christian answer has not proven more livable over the centuries. Christian horrors are on display: Crusades, residential schools. From the beginning forced conversions were acceptable.

A skeptic could say that violence is in Christian faith at the very root. Take the Joshua/Judges command to annihilate the Canaanites, always taken as part of the Christian Bible.

Another skeptic might add: A millennium-and-a-half of European Christian anti-Semitism made the Nazi work possible.

Most of occupied Europe was complicit – even after one grants heroic exceptions.

The recent Kristen Scott Thomas film “Sarah’s Key” nails this, not to mention Ophuls’ “The Sorrow and the Pity” from 1969.

Claude Lanzmann’s documentary – and Raul Hilberg’s research on which it was built – make complicity crystal clear. In the Polish interviewees the anti-Semitism is barely concealed.

A believer in Christ can only affirm: Christianity too stands under the cross.

Perhaps Christianity stands under the cross most of all.

Christians should start by admitting abject failures in all branches of the faith as our own failures, from the get-go.

Christian life must be a repenting life. Now, more than ever.

If repenting tends to go to seed in the second generation, that is a call for strenuous catechesis and evangelism – at least.

The unfair suffering of others – and our complicity – is a call to admit again that Christian morality is only worth the living faith it draws on.

Anyone’s righteousness is only filthy rags.

God is not unfaithful.

Singer’s characters see the options to be mysticism or nihilism. “We don’t know what’s out there,” or, “Life has no meaning.”

Renewal at the foot of the cross is an option considered once, in mockery of a born-again character.

The only way to reconcile the justice of God with his complete final power is this: Only a crucified God as enough.

The theologian Jurgen Moltmann wrote as much. Bonhoeffer’s tortured reflections that led to a religionless or churchless Christianity must have pivoted on the vindication of God.

The triune God is just – despite what we see in our own lives, in current affairs, in history.

That’s why the Cross is a deep enough symbol to sum up the whole faith.

The alternatives are bleak.

God came. Suffered. Rose again.

Hold onto it.

June 5/July 1, 2013

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: education, faith, Holocaust, mission, repentance, theodicy, theology, Trinity, worldview

April 9, 2013

Prayer: Why Bother?

“Why Bother Praying?” is a new title from Paulist Press.

That stark question – by itself – raises interesting rock-bottom issues.

“Why bother” hints at a great reason to bypass prayer:

“Why bother, because what God will do, God will do”?

For a minute, put on the why-bother point of view:

The Christian God is the sovereign ruler of the universe.

He controls the atoms, the cells, the neutrons.

He knows how history will end, already, and knew it from (before) the beginning.

Jesus, after all, is the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world. (Revelation )

So: why pray?

Whatever will be, will be. The future’s not ours to see. Que sera, sera.

He even knows our prayers before we make them.

Why ask him? He already knows what you need. Why clog up communication with needless information?

And, prayers that are in line with the will of God are the only ones that are heard.

Translated: Ask him to do what he is going to do already, and he will do it.

Doesn’t that make praying seem pointless?

Why take time to pray?

The effect of any prayer is already included in the divine plan.

Wait a minute: If the effect of your prayer is already factored into the divine plan, then, suppose you did not pray.

Your non-prayer is part of the divine plan also.

Nobody prayed, so God did nothing!

Here is a confirmation of this line of thinking. Jesus went back to Nazareth, and he could not do much there, because the townspeople did not believe in him.

They did not have faith in him. Maybe they did not have much faith in their God, either, besides doubting Jesus’ credentials; maybe their turning away from God was radical. The account is not specific, perhaps because those who had faith in God were looking for his Messiah, like Simeon or Anna (Luke’s gospel).

Basic point: Your prayers in time make a difference for eternity.

We humans cannot know how God will use our prayer. The book says that the prayer of a righteous person makes a big difference.

The book assures us: God’s people can pray and change the course of history.

God hears. Passages even affirm that he “repented” of some promised judgment.

Looks like good reasons for not praying are theological reasons somehow understood in the wrong light:

The foreknowledge of God.

The nature of faith.

Trust in God as central to the Christian life.

God in time and beyond time, transcendent, and also immanent. Beyond us and with us.

Trusting God in disasters like Habakkuk’s catastrophe.

Believing that the Cross is God’s paradoxical decisive intervention in history.

Jesus prayed!

Why on earth did Jesus have to pray?

If Jesus is the second person of the Trinity, the fact that he prayed is as much mystery as one could imagine.

He even said that the Father knows some things not known by the Son, at least while on Earth. –More mystery.

Then again, Jesus is still praying, Hebrews tells us.

Prayer might be the most central aspect – the defining aspect – of the Christian life, the sign of one’s faith, humility, love, hope, compassion. Maybe.

I’m in Oxford where colleges were founded to pray for the souls of the wealthy departed.

Could one write about great ages of prayer? Great places of prayer?

I hear that Korea knows how to pray.

Could an age of prayer give way to an age of advance for the gospel?

Korea sends many missionaries. The country has changed dramatically. Are these changes from prayers?

“Jesus taught them that they should always pray and never give up.”

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: action, apologetics, faith, pain, paradox, prayer, Scripture, suffering, theodicy, wisdom, witness, work

March 29, 2013

How come Christians mostly talk to similar-minded folks?

When I was training to be a preacher in the early 90s, the most attuned preaching prof advised that we preach as if unbelieving visitors were present.

When I was training to be a preacher in the early 90s, the most attuned preaching prof advised that we preach as if unbelieving visitors were present.

The basis of this advice was a conception that if Jesus Christ brings any difference to, say, your money management, that same ability to bring faith to bear would apply to people who don’t come with faith, as it would apply to people who don’t see how the good news might apply to money management.

Translation: Advice to unbelievers could benefit believers too.

Believers live in the world too, not always relying on a faith approach (surprise!), talking a secular language should work for both kinds of hearers.

The radical idea under the advice is that hearers don’t have to have crossed the threshold into believerdom before they can benefit from a church message.

Contradicting many people, that’s saying: There is not a salvation message, and then a second step, a holiness message.

There is one message of faith in the risen Messiah of Israel, Jesus.

The message is for believers who need to put it into practice, also for unbelievers who need to put it into practice.

So: Preach as if unbelieving visitors are present. The believers will hear you better too.

But:

When I actually got into a church and had to deliver each Sunday, the advice proved hard to implement.

I don’t know exactly why it was so hard to speak as if pre-faith folks were present.

Many messages I developed seemed likely to matter only to church folks.

I’d take a verse, think it through, develop a pile of possible implications, make it as practical as I could.

But as soon as you yield to the temptation to talk in-house on just one day, you are sunk because the members will not know for sure if you are in-house or whole city on any given day. So your Sunday morning space will not be automatically safe for pre-faith people. They might be subject to something that does not concern them.

I was somewhat successful in a wide audience message when I knew for sure that there would be mainly non-church folks present.

The mighty focusing reality forced me to think through the language and thought forms.

I read over my messages now, ten years later, and here is what I think.

These talks might be OK if only church folks were there, but for anyone else they are so dusty. They probably talk past people.

Why, for example, is a post I just made about death so out of it? It seems very Sixties as I read it.

The post tries to get “under” death as a taken-for-granted reality by acknowledging secular ways of dealing with death (that’s the Kubler Ross introduction).

Then I use literature (a Tolstoy story from the late 1800s) to show the horror of death when you are in a process that we tend to ignore during life. Just as Illich ignored the coming reality until struck down.

But, here’s a problem.

People today display no fear of death.

They might even shrug if you talked about it.

“No one knows what happens.”

The conception of sin that drove the fear has evaporated in the era of Freud and more recent therapies.

The pursuit of personal authenticity is much more pressing than moral failure.

Tolstoy is labeled a moralist, after all. His psychology is a moral or religious psychology.

Few people are primarily moralistic now.

Tolstoy’s story is still interesting (I think). Charles Taylor the current philosopher has a piece or two that jigsaws with it – still, even now.

But it is not quite on the track with late-moderns or post-moderns who have been psychologized.

Counselling prof David Powlison once asked a seminary class: How do you intend to do ministry with psychologized people?

Powlison’s question is still a great one. I wish he had said more about it.

If sin-sense seems to be gone, you have to find where the consciousness of sin is hiding out. how the anxieties also manifest themselves today.

The filmmaker Kieslowski did a 1980s film search expedition of just this question. In his series “The Ten Commandments,” each segment works out the persistent effects of disregard of the commandments.

Even though no character has much or any faith.

After all, psychologized or not, we are created in the image of God. We have all done something with God. We all live in his world. He is inescapable.

For the old time preacher, how to find where they’ve hidden him?

Filed under: Uncategorized

Why ever should Jesus on the cross prompt you to trust him for your life?

“Today, you will be with me in Paradise.” (Luke’s gospel chapter 23)

Some of us know about five stages of death.

The first is denial and isolation.

The second is anger.

The third is bargaining.

The fourth, when things are definitely not going to get better, is depression.

And then, supposedly, the fifth stage is acceptance.

Eighty years before Elizabeth Kubler-Ross thought up this five stage scheme, the very realistic Russian writer Tolstoy showed us the death of Ivan Illich.

Tolstoy’s Illich has been a lawyer and judge.

Illich has gone from position to higher position with hardly a hitch. He lived for getting honour in his good job at his career and for recognition in society, for his own pleasure.

Suddenly at age 45 he comes down with a pain in his side. The mysterious pain grows worse and worse.

Over weeks it becomes clear to everyone around that Judge Illich is dying.

For everyone else death is outside them. Like Illich himself until now, death happens to other people.

He has become just an invalid, a burden.

He is an inconvenience to all whose lives go on.

No one will tell him that he is dying.

His life has been a self seeking lie but he cannot quite see through it. And the pain will not go away.

Now, shift the scene:

In the year 33 on this hill outside Jerusalem – two executions are going on, besides Jesus.

Jesus the rabbi from Galilee. Jesus is crucified with a couple of criminals.

Three executions. Three naked human beings. Three humiliations. Three failures.

The criminals react to Jesus in two different ways. One mocked Jesus and would not believe.

The other repented and trusted him.

Luke 23:39-44 reads, (NIV) One of the criminals who hung there hurled insults at him: “Aren’t you the Messiah? Save yourself and us!”

But the other criminal rebuked him. “Don’t you fear God,” he said, “since you are under the same sentence? We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve. But this man has done nothing wrong.”

Then he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

Jesus answered him, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise.”

Isn’t this scene exactly what we find in regular life? Just like the mocking criminal, there are people who just make fun of believers.

Many see no difference in living for Jesus.

Others see their need and believe.

Something in the situation led criminal Two to see himself. For what he was. To see Jesus. For who he really is.

Criminal One mocks. Aren’t you the Christ? -the Messiah we expected? -the savior?

But see it makes no difference, Christ, Messiah, savior, you end up here just like the rest of us. There is no hope from you.

But he missed himself. He missed his own situation. He is dying.

Why are there not more deathbed repentances? We are hardened. We fail to understand the horror of dying. The flow of life hides it. We have to stop and think and that sometimes takes quite a knock.

Sometimes even being on the edge of death doesn’t do it.

Criminal Two saw it clearer. Don’t you fear God? You are under the same sentence. In fact, WE ALL DIE.

Jesus should prompt you to repent. Criminal Two said: he has done nothing wrong. But you have. All of us have.

No one has done no shameful things.

No one has failed to forgive.

No one has not had deep desires for this or that which God has not given as yours.

No one has not committed character assassination.

But Jesus is innocent. He did nothing wrong. He did nothing to deserve death.

He makes the horror of dying clear. We deserve death. He did not. Our sin put him there.

Jesus should prompt you to repent because he is able to save you.

Criminal Two said, Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.

Jesus accepted many unacceptable people. Jesus’ care was evident. Criminal Two does not mock Jesus the savior king. He confesses his faith.

“You are going to get a kingdom. You are the Messiah. At the end of time, think of me. That will be enough for me to be OK. Remember me. Rescue me. I think I may be some place suffering torment, but remember me when you win. God is with you. I trust you. You can get me out of there. Save me.”

Jesus said: I say to you, not sometime down the road, but TODAY you will be with me in Paradise.

Here is the word of the king. I say to you — verily verily — you can count on it — Amen, amen — my word is as reliable as the fact that the sun comes up every day.

Today you will be with me. I speak and it happens. My word goes out and accomplishes what it is sent for. Even on the seeming failure of the cross Jesus is Lord.

Today. Go in peace, your faith has saved you.

If there was ever a clear show of the fact that Jesus saves, not our efforts, not what we do for the Lord — or don’t do — it is here.

At the end of a wretched life, totally misspent, God gives this criminal the grace, the smarts, the courage to cry out for mercy. A misspent life but an eternity with Christ.

Today. You can die in peace. You can face it. You have Jesus’ word: today. Absent from the body is present with the Lord.

And this is what Ivan Illich finally came to in Tolstoy’s account.

By the grace of God, through the pain, he asks the impossible question: did I live my whole life wrong? After he receives the formal communion something clicks for him, something he has overlooked, something that takes away all the falsity and lying of his family and friends.

Do you need a fresh view of the cross? Paul says to the Galatian Christians: I made you see Jesus Christ Messiah Savior clearly pictured: crucified.

Have you forgotten that Jesus takes away sin by his cross — for you? Have you forgotten to keep repenting in the light of the cross — to live out your faith by putting off the old and putting on the new person?

The cross is the word of mercy.

There is a right reaction to Jesus on the cross. Jesus on the cross should prompt you to repent.

He should prompt you to repent because you will die too.

He should prompt you to repent because you are guilty.

He should prompt you to repent because he can save you when you trust him.

TODAY you will be with me in Paradise.

Filed under: Uncategorized

Did Jesus Die for Hitler’s Sins?

Thinking out loud.

Today is Good Friday.

A friend of mine said that Jesus died for everyone’s sins, for the world – for Hitler’s sins.

I’ve been reading journalist Peter Maas’s 1996 book on the Bosnian war, Love Thy Neighbour.

Human sin goes very wide in the book. The criminal averted eyes of Western leaders come off as hardly less heinous than the concentration camp guard who roped a Muslim’s genitals to a motorcycle and accelerated away.

Maas has sensitive insight because he doesn’t demonize the Serbs; he makes the potential demonic to be as wide as the human race, including a good selection of his own self-protective actions.

Do anyone’s sins, say, those of pedophile rapist Major Michael Pepe, keep one from God’s kind presence?

If Jesus died for Hitler’s sins, is Hitler to enjoy eternal life?

Universalism is the belief that every single human being, good, bad, and mediocre, will be saved at the end.

Probably universalism is not usually meant when Christians affirm, “Jesus died for all.”

But if a sufficient sacrifice exists for my sins, then how can God be so unjust as not to accept it?

The whole point of Jesus’ death on the cross is that his sacrifice avails for my past deeds, my present deeds, even, when they come, my future deeds.

If I keep faith with the Son of God, he will justify me finally as he has already done incipiently (Romans 3).

And he knows those who are his, so he knows already whether I will hit some event in future which is just too big for my puny faith, and when I will turn away from him saying, Impossible.

Many must have lost their faith in the Holocaust, in Bosnia, in Rwanda, perhaps after 9-11.

Many must have lost their faith in the Holocaust, in Bosnia, in Rwanda, perhaps after 9-11.

To the contrary, many realized that these horror show events just put the theodicy question in the starkest possible form: “Is the monotheist’s God really just? Is he fair?” And they may have decided to believe, no matter what.

Maas met a faithful Catholic who gave the affirmative answer, and says that he has been wondering about her ever since. Was she naïve? Or was she exactly correct?

Maybe one could say that God is good to us so that the horror shows are repeated relatively rarely – though, again, someone else could beg to differ.

If God saw the need for a sacrifice for sin to the amazing, awful extent of his own Son, you could say that he is not naïve about human negative potentials.

God on the cross is the only God worth worshipping, as many have observed, and from which many have turned away. The event is an interpretive crux, so to speak. “Who is God? Can I believe in him in this evident hell?”

Were Hitler’s sins forgiven? If Hitler died repentant, the answer would be yes. So we do not know.

If we take the evidence of those in the May 1945 bunker and the fact of his suicide, again, not conclusive evidence, we say: Probably he died unrepentant. The sacrifice which my friend attributed to Herr Hitler remained, er, inert, unactivated, unactualized.

I prefer to say that Hitler had no sacrifice, but maybe it seems like splitting hairs. Hitler had a potential sacrifice, but in fact, that is, most likely, Hitler had no sacrifice because he had not picked it up and presented it to God.

So Jesus did not die for Hitler’s sins, that is, most likely not.

Jesus died for the sins of those who would repent and believe.

If we believe that God knows everything – indeed, works everything out for good – then he also knows who will believe, who will take for themselves that sacrifice.

God knows the names of the metaphorical 144,000 who stand before his throne.

God knows the names of the uncountable multitude, both of the stars in the sky and of his people in the Book of Revelation chapter 7.

Just read a genealogy in, say, Genesis. God knows his people. This foundation stands, sure and certain: The Lord knows who are his.

Perhaps you are familiar enough with theology to know that what you are reading is partly canned and partly fresh.

You may know that there is such a theology as Calvinism. You might know that it is said that “five points” sum up Calvinism.

In fact, the five points are not a summary of Calvinism.

The five points really only disagree with five other points, from a dissident theologian named Arminius.

Arminius’s five points basically say that humans make up our own minds or else God is not fair.

The supposed ability to decide is the essence of free-will theology. If God ordains or God allows (how much difference is there, really?) then God is not fair. He is a despot.

Okay, I can hear howls of protest.

But if God withholds some power or some favour that is needed for satisfactory performance, then how different is that than God acting to bring X about?

The basic thing is, if good happens, thank God. You did not make it happen.

If bad happens, put your hand over your mouth and do not blame God.

Either good or bad, one must revere and be in awe of God.

Isn’t respect the message of Job’s book of wisdom?

The God who makes things happen is the Big God. That is Augustine’s God, controversial from Day One, but the only God who can hold the water we need him to hold.

The five points of Calvinism are not divisible. They go together. They make sense together. They form the acrostic T.U.L.I.P.

The five points are:

Total Depravity. Humans, not as bad as could be, are infected by sin in every capacity, every thought, every action. Nothing is unstained.

Unconditional Election: you did nothing to make you right with God before he chose you. This is cause for humility, big-time.

Limited Atonement: Jesus died for the elect, not indiscriminately for the whole world, though potentially (all these words are tricky) potentially for the whole world should the whole world (have) repent(ed). Jesus died for the true church, that is, the elect within the large number of outward, professing, Christians.

Irresistible Grace. Human will is bent away from God from conception onwards. God makes your will truly free at the point you accept Christ. It was never free before. Christ looked like stupid humiliation to you before. When God changes your way of thinking, you think Jesus looks so amazingly good, because God freed your will: “Long my imprisoned spirit lay, fast bound in sin and nature’s night. Thine eye diffused a quickening ray. I woke, the dungeon flamed with light.” Funny to quote a Wesley on this, since John and Charles were not five-pointers at all, but he has this exactly right.

Perseveance of the saints. If you are his, you will keep going, right to the end. The challenges to faith will not fell you, though you can be practically wrecked by them. Look at Job. But he still kept believing, like the Catholic woman in Bosnia. He belonged. She belongs.

The Lord Knows Who are His. TULIP.

OKAY! you say. Enough. Yes, it is Good Friday so some soul searching is in order. This stuff is deep enough – though not likely precise enough.

If you believe, you are not your own; you were bought with a (steep) price.

Let’s honour God and rely on him the way we really are relying on him. Faith is a victory, and that’s apparent in Tulip.

And the human action prayer starts to look like the most amazing thing in human experience period. God is at work in you to will and to do. Wow. Awe.

Your comment is totally welcome.

Filed under: Uncategorized