Roger W. Lowther's Blog, page 5

December 10, 2022

39. A Thread x A Thread — Art of Chiyoko Myose

Welcome to the Art Life Faith podcast. This is the show where we talk about art, what it has to do with your life, and what it has to do with the Christian faith. And I’m your host, Roger Lowther.

For over a decade now, we’ve been hosting “Art Life Faith” gatherings around Tokyo where we share a meal together and then an artist, a different artist each time, shares a little bit about their work and then we discuss it together. What does their art have to do with our lives? What does it have to do with our faith? The themes are always different, given by artists who are experts in their fields: musicians, dancers, painters, photographers, and the like.

These “Art Life Faith” conversations have been a great space for everyone involved, as we struggle together with what our faith has to do with our art. We teach and encourage each other in ways impossible outside of community, and no one is more rewarded by these relationships than I am. I’m always excited to learn more about God embedded in Japanese culture in ways I never imagined possible.

And there are so many other good things that come from these discussions as well. Let me just share a quick story with you. Just the other day I was visiting a gallery to encourage an artist showing her work here in the city. She was doing an artist talk and interacting with people about her work. I met another artist there who had spoken at a previous event with us. So I introduced myself and said, “I remember you.”

She asked, “Where? Where did we meet?”

“Oh, at that art life event at so-and-so’s house,” I told her.

“That event changed everything for me. I can’t tell you how wonderful it was. After I tried to express my faith in words for the first time, connected to my art, everything took off from there. I started to try to make all these different kinds of artwork to express my faith, and I started telling more and more people about it, and I was able to bring in people and talk about the artwork and talk about my faith. And that was just an amazing opportunity for me.”

I thought, “That is exactly why we’re doing events like this.”

But unfortunately, during these discussions, only a small group of people are ever actually able to be there in person. And then during COVID, well as you know, no one was able to be there at all. We had to move the discussions online. Now thankfully, things have opened up a little bit, but during COVID it really was helpful to look into how we could get these discussions out to more people. How can we involve them in these discussions?

Well, one way was by writing books. My book, The Broken Leaf, is a good example of that. It has ten meditations of the gospel through Japanese art and culture. In one sense it’s a work of journalism, a reporting on our “Art Life Faith” discussions in print form so that people can see what we’re talking about and be drawn into the discussions.

More recently, we started this podcast. Thank you so much for your support of it! We’ve had thousands of downloads since we started, and recently I received an email recognizing us as one of the top listened-to Christian podcasts in Japan. Now, I’m not sure if there are any other Christian podcasts in Japan, so it probably doesn’t mean very much. And, of course, this show is only in English, but we’ve always wanted to get a Japanese version going. So that’s something to look forward to in the future too, as we keep trying to get the message out there to more people.

So, anyway, in today’s episode, I want to bring you into conversations we had about the artwork of Chiyoko Myose, a Japanese artist who now lives in Wichita, Kansas. She came to Japan to exhibit at a gallery in Asuka, Nara, a city that’s south of us, but while she was here we also invited her to exhibit in at Minami Terrace, or “Mina Tera” as we like to call it, a gallery/event space run by our very own Mayuko Shono, an intern working with us here in Tokyo. And then the work was moved to the lobby outside where we meet for worship on Sundays, and we had the privilege of the artist sharing her faith through the artwork in the worship service itself.

Chiyoko moved to the U.S. about 25 years ago, which led her to think about themes of being a traveler and a sojourner, with a longing for a place that she could call home. And she invites all of us to think about those themes along with her through her artwork.

Here is a short clip from the opening to our “Art Life Faith” event with our intern, Mayuko, introducing it and my wife, Abi, translating.

[Sound clip from exhibit]

As you can tell from this, it’s a pretty fun and informal event. Chiyoko began by sharing a little bit about her mother, who apparently was really good at talking to people and could become friends with anyone. In the train, in the bus, she would just talk to people. And when she visited Chiyoko in America, even though she didn’t know English very well, she would talk to anyone in her broken English and made friends with so many. She clearly loved meeting people and treasured memories of meeting with each person. Unfortunately, her mother became very sick, and during that time someone gave her a lot of thread and asked if she could make something with it. Chiyoko thought about it and realized that thread really is a very good metaphor for human relationships. She thought of Japanese phrases like 縁を結ぶ (en o musubu), weaving a relationship together, and 縁が切る (en ga kiru), “cutting off a relationship. In fact, the character for “thread” 糸 (ito) is found in many other Japanese characters.

Are you ready for a Japanese lesson? Okay, let’s go. For example, 結ぶ (musubu) “to tie,” 編む (amu) “to knit,” 織る (oru) “to weave,” 縫う(nuu) “to sew,” 紡ぐ (tsumugu) “to spin yarn,” and others. If you look in the show notes, you can see that the left side of each of these characters has a part that looks like the character for “thread.” This is called the ito hen or thread radical.

But, you know, this radical for “thread” is not just found in words that have to do with an actual working with thread. It’s also found throughout the Japanese language in characters having to do with relationships. Besides the two mentioned before, here are two more: 繋ぐ (tsunagu) “to tie together or connect in relationship” and 絆 (kizuna) “bond between people.” In the time leading up to Tokyo Olympics, I saw these two characters everywhere. They were on posters. They were on T-shirts and all kinds of paraphernalia. “絆を繋げよう” (kizuna o tsunageyou). A good translation of that might be something like “Let’s connect in bonds together!” This “thread” radical is in both of those words, “bonds” and “connecting.” And I also saw both of these characters everywhere after the 2011 earthquake where we were coming together as a nation to meet the challenges of that terrible time.

Another word with the thread radical is 組む (kumu) “to organize.” My youngest son is in the second “kumi” of his fourth grade class. There are four groups in the fourth grade, and he is in the second one. So he’s in the “second kumi.” Another could be紹介 (shoukai) “an introduction, the start of a new relationship and perhaps 契約 (keiyaku) “a contract or binding agreement.” When parties tie themselves together in some mutually agreed upon terms, it’s called a keiyaku. And what about 結婚 (kekkon), the marriage between two people.There are so many words like this that have the thread radical in those characters.

And this “thread” radical is also found in verbs for the end of relationships: 終わる (owaru) “to end,” 絶える (taeru) “to break off,” 絡まる (karamaru) and 絡れる (motsureru) “to get tangled up.”

So in all these different ways, the Japanese language itself expresses relationships based on thread. And Chiyoko does a wonderful job of expressing this through her art. Sewing, tying, braiding, and stringing thread together—through all these methods she’s able to give us different perspectives on relationships.

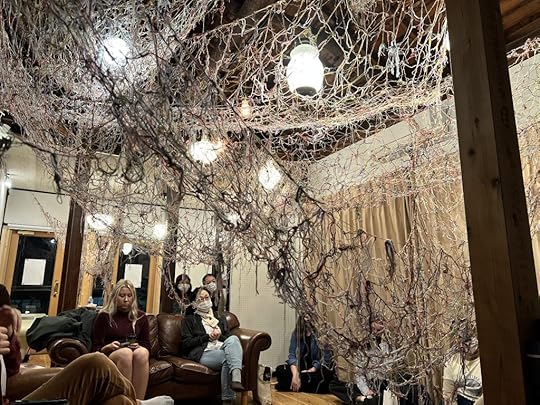

There were two main works Chiyoko exhibited when she was with us. One was called A Thread x A Thread. Each thread is only about 10 inches long, but in the whole work, there’s miles and miles of it. Each thread represents a person. Each knot represents the meeting of people. She started this work in 2013 but ever since, people have been adding to it. And it has grown and will always continue to grow.

First, you have to realize how large this work is. It completely filled the space at Mina Tera and completely changed the atmosphere of the room. That’s one of the gifts of installation art, right? To create a certain atmosphere that people can be drawn into. And we definitely saw that in this case. As we talked to people, we had to shimmy around and through and under the work. But rather than hindering the building of community, it added to the experience. Usually when you walk into a gallery, you’re not allowed to touch the artwork. Your supposed to just look at it. But in this case, it was okay to brush against it and touch it, but you were encouraged to do so. You didn’t have to be afraid of breaking it or hurting it, because you were completely immersed in it. And that was the intent, to envelope the viewers with love as represented by these threads and also with the message of hope and healing. And through the art, different people were connected to each other.

As we added to the work, it became more and more complicated and messy. There were pieces hanging out everywhere. But in the hands of the artist, this was all brought together into one beautiful tapestry. Threads that hung by themselves were tied to others. They were physically brought into the work.

After the gallery showing, the work was transported to the lobby outside our worship space for Grace City Church Tokyo. One couple who came to the gallery had carefully tied their threads together but were disappointed that they couldn’t find their thread again in the new space. It was so clear how their lives, their relationship together, were all connected and part of something bigger, to this bigger community that was around them and with them and encouraging them. And how they too gave back to the community. It was just such a wonderful picture of being church.

I also really appreciated the way it brought in people from the congregation who don’t usually say much and may be a little bit shy. But they were willing to quietly grab a piece of thread and tie it on somewhere. And it gave me a chance to tie on a thread next to them and talk quietly with them. Just through the artwork itself it gave and built a sense of community, exactly what we are trying to be as a church.

Another work that Chiyoko displayed at the gallery and also outside the worship space was a painting series called Iridescence. Iridescence is a phenomenon where surfaces appear to change color depending on what angle you view it from. And it’s meant to be a picture of our lives. By being in community, we’re able to see our life through the different perspectives of different people and how we interact with one another.

In this work, Chiyoko made alternating layers of dry and wet in order to show this. She first would lay down a drawing with pastels, crayons, color pencils, and pens, and also of course thread, she always used thread, and then she would put a wet layer of paint. Sometimes she mixed in gold and silver to give it that iridescent effect. The wet paint would flow up against the thread and along it. Then another layer dry layer is put down. And then again another layer of wet paint. So the finished artwork is a beautiful combination of these three, wet mediums, dry mediums, and thread, interacting and responding to each other. I might even add learning from one another.

Fortunately, we now have two paintings from the Iridescence series hanging in our living room. Our living room is one of the main meeting locations for church gatherings. So many meetings, parties, Bible studies, and training happens here. A lot of community building happens in our living room. So it seemed especially appropriate to have artwork about relationships displayed there, and we look forward to the time when you can see them in person, joining in the church activities and building community with us.

It was really cool to see how Chiyoko brought all this together—her own experiences, her wonderful memories of her mother, and this theme of relationships brought out in the Japanese language as represented with thread. Through her work, we saw a new perspective of the way that God works with us. We’re cut off. We’re separated from one another and lonely. Our threads are fraying and falling apart. We’re unraveling. And yet, through her craft, Chiyoko showed us how the Great Artist takes our tangled and frayed and unraveling lives, and brings us in and ties us to one another and to him. He builds our community and makes unity in him possible through his love. As it says in Colossians 3:14, “love…binds everything together in perfect harmony.” God has fearfully and wonderfully knitted us together in our mother’s womb. He has weaved us together in the depths of the earth, as it says in Psalm 139.

All of this happened for the first Sunday of Advent. What better way to celebrate the true meaning of Christmas? In a profound and mysterious way, God saved the world by coming into the world. He came as a little “thread” to 結ぶ (musubu), “to tie” onto our tangled and fraying lives and communities. Jesus was cut off on the cross that we might be tied to God. He became the isolated and broken strand so that we could be gathered into community with him. In a world quickly unraveling in sin, he binds us together with his love into a big and beautiful tapestry in the peace and harmony of the kingdom of God.

This is Roger Lowther, and you’ve been listening to the “Art Life Faith” podcast. Check out my website, rogerwlowther.com for a transcription of this podcast and links and pictures to Chiyoko’s works. As we say in Japan, “Ja, mata ne! See you next time.”

The post 39. A Thread x A Thread — Art of Chiyoko Myose appeared first on Roger W. Lowther.

November 26, 2022

38. Bach and the Navajo – A Conversation with Samuel Metzger

Welcome to the Art Life Faith Podcast. This is the show where we talk about art, what it has to do with your life, and what has to do with the Christian faith. And I’m your host, Roger Lowther.

In previous podcasts, we’ve talked about the challenges of working as a Western classical musician in a global and missional context. In my first month in Japan, I was helping to lead worship on a pipe organ, which I was asked to do, when an older missionary came up and started to berate me. “You can’t play that kind of music here. It’s completely against everything we’re trying to do for the Japanese church.” In other words, he was not very encouraging!

I was a bit shocked, but I could see his point. As Christians, we want to see the nations of the world worship God in their heart languages…their spoken language, but also their musical language and their cultural language. The music of Messiaen, Vierne, Widor, and all the other Western composers who’ve written for the organ are not part of their heart language…so, doesn’t that mean I shouldn’t play that music while church planting in Japan? I mean, what role do I have, someone trained in distinctly Western styles of music, in bringing the gospel to the people of Japan? How can I justify playing the pipe organ for people in Japan?

Well…this is, of course, one of the key issues we’ve been addressing in many podcasts. The fact that we’ve seen many Japanese become Christians, not by adopting Western cultural forms, but by embracing creative expressions of the gospel in their own culture proves we need to rethink the dilemma. Church planting around the world builds the kingdom of heaven, where all the nations worship God of course through their heart languages. But also, they are led in worship through the heart languages of all other people as well. Just as in Isaiah 6:3 where the angels call, “Holy, holy, holy,” to one another, our worship is enhanced by calling out and sharing the praises of God through our own languages and cultures, our own perspectives and insights and experiences. God is most certainly glorified through it.

When I play the pipe organ in Japan, I build relationships with people that lead to experiencing the gospel. I share myself, and they in turn share themselves with me. And through it, we see Japanese become Christians. Not Western Christians, but Japanese Christians who praise God through their perspectives and lead me in worship through them as well.

So, being an artist and a missionary is not only okay, but it’s helpful. It’s effective. It’s strategic. And we’re going to investigate this a little bit more fully in today’s podcast.

This week I’ll be talking with Samuel Metzger. Samuel and I have a lot of overlapping circles. He is currently the organist at Covenant Presbyterian Church in Nashville, TN, which is a church that has supported me and my family generously as missionaries for many years now. And it’s also where my latest organ album, called COVENANT, was recorded. (You can check out that album and its music in the show notes!) Before that, Samuel was the music director and organist at Second Presbyterian Church in Memphis, TN, another church that supports us very generously. I was also the organist there for a number of years before coming to Japan as a missionary. Before that, he was the organist at Coral Ridge Presbyterian in Florida, a huge TV church with services broadcast around the world. I actually auditioned to be organist at that church but didn’t get the job. When Samuel auditioned, he did get the job! So, obviously, he’s a phenomenal organist. He’s active as a concert artist and was a Fulbright Scholar in Germany. The list goes on. Anyway, I feel privileged to know him and to be able to call him a friend.

The reason I’m bringing Samuel on the show today is because, besides being a stellar musician, he also grew up as a missionary kid working with the Navajo. And so he has something to offer as we seek to understand what does it mean to work as a Western classical musician in a missional context.

Samuel, thank you so much for being here today.

SamuelThank you. It’s great to be here. Thanks for having me.

RogerSo you are a musician and you’ve been a musician your whole life and you are a missionary kid. We’ve had a number of conversations in the past in this podcast about how the two connect, missions and arts. And so I’d like to talk with you a little bit about that and hear some of your history. So let me go back to the beginning, your growing up. Tell me about what it was like being the son of a missionary family.

SamuelWell, I think it’s probably the case for all missionary kids, it is a bit of a unique circumstance because you’re in a foreign place. And even though I grew up in the United States, but being on the mission field, being truly a minority, and for a lot of the time, being home-schooled, the family is very important.

My love of music really came through my father. My father, who is a German immigrant, he’s now passed, loved classical music, loved the music of Bach, loved the organ in particular. Had studied organ privately in his late 20s. So when we went to the mission field, he had this wonderful record collection and conversations, and he would reminisce about programs that he’d gone to at the Eastman School of Music when he lived in Rochester. And I would hear about all of these famous organists and of course, we had the recordings.

RogerSo was he a musician himself or just a music lover?

SamuelMusic lover. He had played for a little bit, but when you start playing an instrument at age 27, regardless of how hard you work, you can’t do it. And then he felt called into ministry.

RogerRight.

SamuelSo I grew up hearing music constantly in the home, even though we were at a place culturally that might have seemed a bit removed from that. But when I was eleven is when I was able to start taking some private lessons at the University in Flagstaff, which was an hour drive from where we were. They had a preparatory school for young kids. So I studied with a student teacher there and actually began on the organ, because we didn’t have a piano, we were given a little electronic organ. And so that was at eleven.

RogerThat’s the way I started as well, on the organ, not on the piano.

SamuelYeah. I think it has definite benefits and definite disadvantages technically as keyboard players will know. Give me counterpoint, I can play that all day. Arpeggios, that’s always not quite as comfortable.

RogerSo what was the ministry that your dad was involved in?

SamuelSo my father was a missionary to the Navajo Indians, and the Navajo Indian Reservation is the largest Native American nation in the country. And it’s all around what’s called the Four Corners there of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. And we were in the portion of the mission field, which is near the Grand Canyon. We were about a 40-minutes drive from the Grand Canyon where we lived. So we had a mission church, which actually was in a mobile home right next to the reservation. You could not be on it as a non-Native American. So we lived right next to the reservation. We would go out in my dad’s old World War II jeep out into the sheep camps and would visit people. Some of the ministry was people coming to the mission church. Others were just people that my dad would visit. The Navajos did not speak English. He had an old-fashioned wind-up record player with sermons on it spoken in their native language. It was kind of funny. After listening to them over and over again, you could predict where the pops and the clicks were in the LP.

Yeah, we’d be out there in the sheep camps, and we’d have fried bread cooked there and lard on an open fire and mutton stew and all those things. And then we’d go back to my home and we’d be hearing a Bach Cantata at night.

RogerWell, yeah, that makes me wonder if he’s carrying this record player to the reservation. Was music a part of this ministry? Was he playing music as well?

SamuelNo, it was not. It was not the kind of record player, I don’t remember why, but it was not the kind that would use the normal magnetic electrical pickup. It was totally acoustical. It was a non-electric system. I don’t know what that particular technology was, but no, it did not play regular LPs.

RogerDid he then do music as a ministry at his house or off the reservation?

SamuelYes. When we were first on the mission field, we actually did meet in our living room and we had the regular mission church. He would refer to classical music and later on, as I was able to play more, for example, I learned all of the Bach Schubler Chorals, and I was able to play them and he would use scripture to talk about the text and he would give a translation. Sometimes my dad would do his own translation that would be more literal, rather than the, what’s it called, versified or has to be rhyming. Right? The Catherine Winkworth translations are beautiful, but they’re not always literal.

RogerSo how did that go? What was the reception? Were there a lot of people there?

SamuelYeah, I think it was well received. It was just sort of part of my dad’s ministry. He loved music and referred to it. And then, we would often at Christmas time, we would have a listening time to listen to the Messiah, the Christmas section, and we would print out the lyrics. And so, the congregation would hear this wonderful music, but then also the gospel story. We did that. And then he would, on occasion, this would be for the more adventurous listeners, he would maybe do a Bach Cantata and then give a translation in English or something like that. But that was probably becoming more of a reach. Handel’s Messiah is probably an easier lift.

RogerWell, I would have enjoyed that.

That’s interesting, though. One of the things that we struggle with in Japan is that whole thing about trying to make sure that Christianity doesn’t look like a Western religion, and so bringing in Bach’s cantatas or Handel’s Messiah or things like that. Do you think there was any of that conflict there? Or how do people…

SamuelI’m not sure that the Navajo people, at least, certainly 30 years ago, would have thought of it that way. I think in our more modern times, people are more and more sensitive to those thoughts. Now, maybe we were just oblivious to it, but I guess in a way, even for the few white people who came to my dad’s church, that was practically just as foreign to them as well.

RogerRight. That’s true.

SamuelThe whole thing was a novelty. It was a novelty that people thought was kind of interesting. You present it without trying to make excuses for it. You just present it, “This is wonderful.” You know, you just present it with the assumption that people are going to like it. My dad always would say, “You have to get the hay out of the hayloft down on the floor where the cows can eat it.” I don’t know if that’s an old German saying or what, but his attitude was, I take that even when I do concerts in church settings, if you tell somebody about a piece of music, give them a hook and you present it in such a way that assumes they’re going to like it, they will, of course, like it. And so I think being not so self-conscious about that, but choosing carefully, you know?

RogerYeah. And I mean, kind of I asked as a devil’s advocate because obviously I’m an organist as well, and I’m playing Bach all the time in Japan, which seems like this Western thing, but it seems too that it’s a chance to say, this is what I have to offer, this is who I am. It’s a way for relationship building rather than some kind of Western domination of culture thing. Just like a sharing time.

SamuelYeah. And I think that it’s being less self-conscious about it. But whatever we present, and particularly those of us as performers, if we do it with passion and excitement, I think that ultimately music is just music and you have to know your congregation. I do remember I come back from Germany having studied all of this high art, and then I end up in a church in South Florida, which was a TV church and really appreciated just the old hymns. So I kind of got a little bit off of my pedestal and realized I could play my Bach and my Vierne and all that. But then if I worked in a nice arrangement of a hymn setting or something that people related to, that bought a lot of buy-in. And in the end, after being there for several years, my solo concerts would get a huge audience. And it wasn’t because they were organ lovers. It’s just they kind of knew that whatever I presented they would like. And so I think it’s presenting things with passion, and I think that’s the key.

RogerThat’s cool. So what about in case of Navajo music? I know they do have a rich heritage, which has really been commercialized when I’ve been out West and seen the dances and various things going on. Were you ever able to sing together in Navajo various songs or hymns that were Christian?

SamuelYeah, there were some songs, particularly with…Well, first of all, most of the Navajos, the young, like young parents and children, a lot of them were already starting to lose their native language. They had become very Westernized, as in language-wise. But there were some songs that we were seeing in our Good News Club with the kids that there were some verses in Navajo that we kind of, my dad and us, as a family learned kind of by rote. So we did have a little bit of that. But they would be Christian songs, but Christian songs that had originally been in English and then been translated. So there was a little bit of a tradition of that. In the actual Navajo music itself, it’s not completely tonal in the sense of what we would think. It was more chanting. And a lot of that had to do with the Navajo religion. So some of that didn’t naturally translate over into the mission. But doing a verse or two of a song in Navajo, that did happen.

RogerAnd how the Navajo react to that? Did they respond well to it?

SamuelYeah, absolutely. And we did a lot of things like, for example, instead of just putting a cross on the wall, we had a Navajo rug made that had a cross. And the offering plate was a Navajo basket. And so we did things to try to incorporate the culture into the services, I think because my father, being an immigrant, understood what it was like to not be a part of the majority culture, he was sensitive to that. He came to this country when he was 16, after World War II, and throughout his whole life never felt truly American, so he was sensitive to other cultures not feeling that way. So I think he related well to it. So he did what he could, I think, to create those bridges.

RogerSo let me jump ahead to modern time and this spread of COVID and this has been hard for a lot of people. I’d love to hear your thoughts about how music had a role to play in healing during this time.

SamuelAbsolutely. Well, for all of us, people in general, but certainly those of us in the arts and those of us who serve in church, it’s been even for us creative people, has taxed us in different ways. We, unfortunately, at the very beginning of the COVID season, we had a pastor catch COVID and die. And so that kind of probably launched us a little bit more quickly into the various measures. We actually went into having to do everything virtual for a couple of weeks while we were waiting to see if any of us had COVID because we’d been in the same room with this pastor. We even recorded things separately in our homes. So I would say it took a lot of flexibility, but the congregation was so appreciative to have some normalcy and we’re blessed, of course, to have had an AV team that could help us make the quality of the audio as good as possible and cameras and all of those things. So we were blessed to have that. But the congregation is really appreciated all that we’ve done and really have reached out. For me as an organist, where I sit normally on Sunday morning, I’m kind of up there doing my thing up there very privately with my back to everybody. But it was interesting that during COVID because of them needing to put something on the screen, they had a camera pointed kind of down at the organ. And so for the first time, a lot of people saw what an organist does and that was interesting. So in a kind of curious way, it raised the people’s appreciation of the organ, which I thought was interesting.

RogerI remembered during COVID, I sometimes watch NBC News from Japan because it’s one of the few that I’m able to watch what’s happening with American news. And Second Pres., your choir, was on the news.

SamuelYes. That was really a wonderful thing that came out of a tragic situation. This pastor who died really loved music, was so supportive of the music. Loved Handel. So he passed away of COVID and the choir, led by our choir director Calvin Ellis, decided to go to his widow’s house and sing a hymn, a cappella. It was a moment when this group of choir members, many who have sung in this choir for 30 years or longer, they’re a group of music lovers, lay musicians, some even have music degrees, but maybe didn’t end up going into music as a full-time career. They took their love of music and then used it to serve the higher purpose of ministering to this widow. And it was posted, I believe, on Instagram or Twitter, and then somehow picked up by NBC News. So that was a really sweet thing that came out of a very sad situation.

RogerYeah, I’m sure it was healing for the choir too, just to have a way to do something that brought light in a dark situation.

SamuelYeah, absolutely. As we know, arts and music and all of these things that we have are what sustain people through difficult times. You can look throughout history…I think of how in my dad’s home country, Germany, how quickly after the war they rebuilt the concert halls or would put on the radio broadcasts of orchestras performing even in rubble, the importance of the arts and what that means for our culture and for those of us who serve and use our music in the church setting. It relates, in some ways, not only musically but then the whole fellowship, the church family, and the spiritual higher purpose of that. So that came together in a wonderful way.

RogerThat’s a great story to end with. Thank you so much for your time, and God bless your ministry and everything you’re doing here.

SamuelWell, thank you. I appreciate it.

RogerThis is Roger Lowther, and you’ve been listening to the Art, Life, Faith Podcast. Check out my website, rogerwlowther.com, for a transcription of this podcast and various links. As we say in Japan, “Ja, mata ne! See you next time!”

The post 38. Bach and the Navajo – A Conversation with Samuel Metzger appeared first on Roger W. Lowther.

Bach and the Navajo – A Conversation with Samuel Metzger

Welcome to the Art Life Faith Podcast. This is the show where we talk about art, what it has to do with your life, and what has to do with the Christian faith. And I’m your host, Roger Lowther.

In previous podcasts, we’ve talked about the challenges of working as a Western classical musician in a global and missional context. In my first month in Japan, I was helping to lead worship on a pipe organ, which I was asked to do, when an older missionary came up and started to berate me. “You can’t play that kind of music here. It’s completely against everything we’re trying to do for the Japanese church.” In other words, he was not very encouraging!

I was a bit shocked, but I could see his point. As Christians, we want to see the nations of the world worship God in their heart languages…their spoken language, but also their musical language and their cultural language. The music of Messiaen, Vierne, Widor, and all the other Western composers who’ve written for the organ are not part of their heart language…so, doesn’t that mean I shouldn’t play that music while church planting in Japan? I mean, what role do I have, someone trained in distinctly Western styles of music, in bringing the gospel to the people of Japan? How can I justify playing the pipe organ for people in Japan?

Well…this is, of course, one of the key issues we’ve been addressing in many podcasts. The fact that we’ve seen many Japanese become Christians, not by adopting Western cultural forms, but by embracing creative expressions of the gospel in their own culture proves we need to rethink the dilemma. Church planting around the world builds the kingdom of heaven, where all the nations worship God of course through their heart languages. But also, they are led in worship through the heart languages of all other people as well. Just as in Isaiah 6:3 where the angels call, “Holy, holy, holy,” to one another, our worship is enhanced by calling out and sharing the praises of God through our own languages and cultures, our own perspectives and insights and experiences. God is most certainly glorified through it.

When I play the pipe organ in Japan, I build relationships with people that lead to experiencing the gospel. I share myself, and they in turn share themselves with me. And through it, we see Japanese become Christians. Not Western Christians, but Japanese Christians who praise God through their perspectives and lead me in worship through them as well.

So, being an artist and a missionary is not only okay, but it’s helpful. It’s effective. It’s strategic. And we’re going to investigate this a little bit more fully in today’s podcast.

This week I’ll be talking with Samuel Metzger. Samuel and I have a lot of overlapping circles. He is currently the organist at Covenant Presbyterian Church in Nashville, TN, which is a church that has supported me and my family generously as missionaries for many years now. And it’s also where my latest organ album, called COVENANT, was recorded. (You can check out that album and its music in the show notes!) Before that, Samuel was the music director and organist at Second Presbyterian Church in Memphis, TN, another church that supports us very generously. I was also the organist there for a number of years before coming to Japan as a missionary. Before that, he was the organist at Coral Ridge Presbyterian in Florida, a huge TV church with services broadcast around the world. I actually auditioned to be organist at that church but didn’t get the job. When Samuel auditioned, he did get the job! So, obviously, he’s a phenomenal organist. He’s active as a concert artist and was a Fulbright Scholar in Germany. The list goes on. Anyway, I feel privileged to know him and to be able to call him a friend.

The reason I’m bringing Samuel on the show today is because, besides being a stellar musician, he also grew up as a missionary kid working with the Navajo. And so he has something to offer as we seek to understand what does it mean to work as a Western classical musician in a missional context.

Samuel, thank you so much for being here today.

SamuelThank you. It’s great to be here. Thanks for having me.

RogerSo you are a musician and you’ve been a musician your whole life and you are a missionary kid. We’ve had a number of conversations in the past in this podcast about how the two connect, missions and arts. And so I’d like to talk with you a little bit about that and hear some of your history. So let me go back to the beginning, your growing up. Tell me about what it was like being the son of a missionary family.

SamuelWell, I think it’s probably the case for all missionary kids, it is a bit of a unique circumstance because you’re in a foreign place. And even though I grew up in the United States, but being on the mission field, being truly a minority, and for a lot of the time, being home-schooled, the family is very important.

My love of music really came through my father. My father, who is a German immigrant, he’s now passed, loved classical music, loved the music of Bach, loved the organ in particular. Had studied organ privately in his late 20s. So when we went to the mission field, he had this wonderful record collection and conversations, and he would reminisce about programs that he’d gone to at the Eastman School of Music when he lived in Rochester. And I would hear about all of these famous organists and of course, we had the recordings.

RogerSo was he a musician himself or just a music lover?

SamuelMusic lover. He had played for a little bit, but when you start playing an instrument at age 27, regardless of how hard you work, you can’t do it. And then he felt called into ministry.

RogerRight.

SamuelSo I grew up hearing music constantly in the home, even though we were at a place culturally that might have seemed a bit removed from that. But when I was eleven is when I was able to start taking some private lessons at the University in Flagstaff, which was an hour drive from where we were. They had a preparatory school for young kids. So I studied with a student teacher there and actually began on the organ, because we didn’t have a piano, we were given a little electronic organ. And so that was at eleven.

RogerThat’s the way I started as well, on the organ, not on the piano.

SamuelYeah. I think it has definite benefits and definite disadvantages technically as keyboard players will know. Give me counterpoint, I can play that all day. Arpeggios, that’s always not quite as comfortable.

RogerSo what was the ministry that your dad was involved in?

SamuelSo my father was a missionary to the Navajo Indians, and the Navajo Indian Reservation is the largest Native American nation in the country. And it’s all around what’s called the Four Corners there of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. And we were in the portion of the mission field, which is near the Grand Canyon. We were about a 40-minutes drive from the Grand Canyon where we lived. So we had a mission church, which actually was in a mobile home right next to the reservation. You could not be on it as a non-Native American. So we lived right next to the reservation. We would go out in my dad’s old World War II jeep out into the sheep camps and would visit people. Some of the ministry was people coming to the mission church. Others were just people that my dad would visit. The Navajos did not speak English. He had an old-fashioned wind-up record player with sermons on it spoken in their native language. It was kind of funny. After listening to them over and over again, you could predict where the pops and the clicks were in the LP.

Yeah, we’d be out there in the sheep camps, and we’d have fried bread cooked there and lard on an open fire and mutton stew and all those things. And then we’d go back to my home and we’d be hearing a Bach Cantata at night.

RogerWell, yeah, that makes me wonder if he’s carrying this record player to the reservation. Was music a part of this ministry? Was he playing music as well?

SamuelNo, it was not. It was not the kind of record player, I don’t remember why, but it was not the kind that would use the normal magnetic electrical pickup. It was totally acoustical. It was a non-electric system. I don’t know what that particular technology was, but no, it did not play regular LPs.

RogerDid he then do music as a ministry at his house or off the reservation?

SamuelYes. When we were first on the mission field, we actually did meet in our living room and we had the regular mission church. He would refer to classical music and later on, as I was able to play more, for example, I learned all of the Bach Schubler Chorals, and I was able to play them and he would use scripture to talk about the text and he would give a translation. Sometimes my dad would do his own translation that would be more literal, rather than the, what’s it called, versified or has to be rhyming. Right? The Catherine Winkworth translations are beautiful, but they’re not always literal.

RogerSo how did that go? What was the reception? Were there a lot of people there?

SamuelYeah, I think it was well received. It was just sort of part of my dad’s ministry. He loved music and referred to it. And then, we would often at Christmas time, we would have a listening time to listen to the Messiah, the Christmas section, and we would print out the lyrics. And so, the congregation would hear this wonderful music, but then also the gospel story. We did that. And then he would, on occasion, this would be for the more adventurous listeners, he would maybe do a Bach Cantata and then give a translation in English or something like that. But that was probably becoming more of a reach. Handel’s Messiah is probably an easier lift.

RogerWell, I would have enjoyed that.

That’s interesting, though. One of the things that we struggle with in Japan is that whole thing about trying to make sure that Christianity doesn’t look like a Western religion, and so bringing in Bach’s cantatas or Handel’s Messiah or things like that. Do you think there was any of that conflict there? Or how do people…

SamuelI’m not sure that the Navajo people, at least, certainly 30 years ago, would have thought of it that way. I think in our more modern times, people are more and more sensitive to those thoughts. Now, maybe we were just oblivious to it, but I guess in a way, even for the few white people who came to my dad’s church, that was practically just as foreign to them as well.

RogerRight. That’s true.

SamuelThe whole thing was a novelty. It was a novelty that people thought was kind of interesting. You present it without trying to make excuses for it. You just present it, “This is wonderful.” You know, you just present it with the assumption that people are going to like it. My dad always would say, “You have to get the hay out of the hayloft down on the floor where the cows can eat it.” I don’t know if that’s an old German saying or what, but his attitude was, I take that even when I do concerts in church settings, if you tell somebody about a piece of music, give them a hook and you present it in such a way that assumes they’re going to like it, they will, of course, like it. And so I think being not so self-conscious about that, but choosing carefully, you know?

RogerYeah. And I mean, kind of I asked as a devil’s advocate because obviously I’m an organist as well, and I’m playing Bach all the time in Japan, which seems like this Western thing, but it seems too that it’s a chance to say, this is what I have to offer, this is who I am. It’s a way for relationship building rather than some kind of Western domination of culture thing. Just like a sharing time.

SamuelYeah. And I think that it’s being less self-conscious about it. But whatever we present, and particularly those of us as performers, if we do it with passion and excitement, I think that ultimately music is just music and you have to know your congregation. I do remember I come back from Germany having studied all of this high art, and then I end up in a church in South Florida, which was a TV church and really appreciated just the old hymns. So I kind of got a little bit off of my pedestal and realized I could play my Bach and my Vierne and all that. But then if I worked in a nice arrangement of a hymn setting or something that people related to, that bought a lot of buy-in. And in the end, after being there for several years, my solo concerts would get a huge audience. And it wasn’t because they were organ lovers. It’s just they kind of knew that whatever I presented they would like. And so I think it’s presenting things with passion, and I think that’s the key.

RogerThat’s cool. So what about in case of Navajo music? I know they do have a rich heritage, which has really been commercialized when I’ve been out West and seen the dances and various things going on. Were you ever able to sing together in Navajo various songs or hymns that were Christian?

SamuelYeah, there were some songs, particularly with…Well, first of all, most of the Navajos, the young, like young parents and children, a lot of them were already starting to lose their native language. They had become very Westernized, as in language-wise. But there were some songs that we were seeing in our Good News Club with the kids that there were some verses in Navajo that we kind of, my dad and us, as a family learned kind of by rote. So we did have a little bit of that. But they would be Christian songs, but Christian songs that had originally been in English and then been translated. So there was a little bit of a tradition of that. In the actual Navajo music itself, it’s not completely tonal in the sense of what we would think. It was more chanting. And a lot of that had to do with the Navajo religion. So some of that didn’t naturally translate over into the mission. But doing a verse or two of a song in Navajo, that did happen.

RogerAnd how the Navajo react to that? Did they respond well to it?

SamuelYeah, absolutely. And we did a lot of things like, for example, instead of just putting a cross on the wall, we had a Navajo rug made that had a cross. And the offering plate was a Navajo basket. And so we did things to try to incorporate the culture into the services, I think because my father, being an immigrant, understood what it was like to not be a part of the majority culture, he was sensitive to that. He came to this country when he was 16, after World War II, and throughout his whole life never felt truly American, so he was sensitive to other cultures not feeling that way. So I think he related well to it. So he did what he could, I think, to create those bridges.

RogerSo let me jump ahead to modern time and this spread of COVID and this has been hard for a lot of people. I’d love to hear your thoughts about how music had a role to play in healing during this time.

SamuelAbsolutely. Well, for all of us, people in general, but certainly those of us in the arts and those of us who serve in church, it’s been even for us creative people, has taxed us in different ways. We, unfortunately, at the very beginning of the COVID season, we had a pastor catch COVID and die. And so that kind of probably launched us a little bit more quickly into the various measures. We actually went into having to do everything virtual for a couple of weeks while we were waiting to see if any of us had COVID because we’d been in the same room with this pastor. We even recorded things separately in our homes. So I would say it took a lot of flexibility, but the congregation was so appreciative to have some normalcy and we’re blessed, of course, to have had an AV team that could help us make the quality of the audio as good as possible and cameras and all of those things. So we were blessed to have that. But the congregation is really appreciated all that we’ve done and really have reached out. For me as an organist, where I sit normally on Sunday morning, I’m kind of up there doing my thing up there very privately with my back to everybody. But it was interesting that during COVID because of them needing to put something on the screen, they had a camera pointed kind of down at the organ. And so for the first time, a lot of people saw what an organist does and that was interesting. So in a kind of curious way, it raised the people’s appreciation of the organ, which I thought was interesting.

RogerI remembered during COVID, I sometimes watch NBC News from Japan because it’s one of the few that I’m able to watch what’s happening with American news. And Second Pres., your choir, was on the news.

SamuelYes. That was really a wonderful thing that came out of a tragic situation. This pastor who died really loved music, was so supportive of the music. Loved Handel. So he passed away of COVID and the choir, led by our choir director Calvin Ellis, decided to go to his widow’s house and sing a hymn, a cappella. It was a moment when this group of choir members, many who have sung in this choir for 30 years or longer, they’re a group of music lovers, lay musicians, some even have music degrees, but maybe didn’t end up going into music as a full-time career. They took their love of music and then used it to serve the higher purpose of ministering to this widow. And it was posted, I believe, on Instagram or Twitter, and then somehow picked up by NBC News. So that was a really sweet thing that came out of a very sad situation.

RogerYeah, I’m sure it was healing for the choir too, just to have a way to do something that brought light in a dark situation.

SamuelYeah, absolutely. As we know, arts and music and all of these things that we have are what sustain people through difficult times. You can look throughout history…I think of how in my dad’s home country, Germany, how quickly after the war they rebuilt the concert halls or would put on the radio broadcasts of orchestras performing even in rubble, the importance of the arts and what that means for our culture and for those of us who serve and use our music in the church setting. It relates, in some ways, not only musically but then the whole fellowship, the church family, and the spiritual higher purpose of that. So that came together in a wonderful way.

RogerThat’s a great story to end with. Thank you so much for your time, and God bless your ministry and everything you’re doing here.

SamuelWell, thank you. I appreciate it.

RogerThis is Roger Lowther, and you’ve been listening to the Art, Life, Faith Podcast. Check out my website, rogerwlowther.com, for a transcription of this podcast and various links. As we say in Japan, “Ja, mata ne! See you next time!”

The post Bach and the Navajo – A Conversation with Samuel Metzger appeared first on Roger W. Lowther.

November 12, 2022

37. Imaginative Expression Specialists — A Conversation with Byron Spradlin

Welcome to the Art Life Faith Podcast. This is the show where we talk about art, what it has to do with your life, and what has to do with the Christian faith. And I’m your host, Roger Lowther.

In the previous episode, I interviewed author Bruce Young and his wife Susan about his latest book, Living in Full View of the God of Grace. Thank you so much for your support of that book. We hit number one on Amazon in a number of categories, and it’s our hope that this book will be a blessing to many as it helps all of us see more and more clearly the God of grace.

I’m also excited to announce that my latest album, Covenant, has just been released. It’s available wherever you buy music, Apple Music or Amazon. You can also listen to it on Spotify and YouTube, so I encourage you to check it out. It was definitely a labor of love with some pieces I’ve been wanting to record for a really long time. On one of my trips to the US, I started by flying to Nashville, where I stayed on the Japan time zone for a few days so I could record all night long when the building was quiet and sleep all day. At the end of the week, I gave a concert. It was a pretty cool experience, and I’m really happy with how the project turned out.

I’ve been playing music my whole life. It’s not just something I do. It’s part of who I am. And like a lot of artists, the lines are a bit blurred between this “being” and “doing.” When you spend every waking moment focused on one thing, you kind of get rewired that way. But it’s also one more way that COVID hit particularly hard. As an organist, I depend on other spaces to play music and on people to gather to hear it. And here in Japan, things were shut down a lot harder and a lot longer than in the US. But even in the US, it was difficult. I had a terrible time finding places to practice because of COVID concerns, and concerts were basically out of the question during that time. But of course, some of my friends had it a lot worse than me. At least I still received a salary as a missionary. They, on the other hand, still depended on every single gig for a paycheck. And there weren’t many gigs. I know musicians who had to entirely give up their performing careers.

Yet, some of us could turn to other ways to share their creativity, and today I’d like to share one of those stories, about a dance company here in Tokyo, the Minato City Ballet Company. Because of COVID, they were forced to move online. Prices for cameras and livestreaming equipment skyrocketed, and for a really long time, a lot of things are actually sold out, not available anywhere. So they invested in what they could find and managed as best they could. The biggest challenge of all, though, was continuing to teach, which is the bulk of their income. And they didn’t give up. They figured out which platforms to use, how to collect payments, and all the rest.

The assistant director of the company, Natsko Goto, an award-winning ballerina, also took up photography. And then, she started entering those photographs into competitions and won numerous awards, especially for the picture titled How Beautiful are the Feet. It’s based on the scripture verse from Romans 10, “How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news.” It’s a pretty popular verse at foreign missions conferences. The Apostle Paul says that people around the world will not know the gospel unless they’re told, and that they’re being told through all things that are made by God and by man. And this includes the work of dancers and every other artist from every nation and culture.

How Beautiful are the Feet

How Beautiful are the FeetThe message of the gospel is beautiful, but so are the feet of the messengers, the means by which that message is communicated. And so this ballet company, run by Christians, actively seeks to communicate the message of the gospel through their art, through their dance. In the photograph, How Beautiful are the Feet, we see a circle showing only the feet of the dancers. On one foot, they wear a point shoe. On the other, the foot is completely bare. One foot is dressed for being on stage, beautifully presentable. The other, not so much. It shows evidence of the blood, sweat, and tears—the bruises, pain, and injury. Feet are the means by which the Minato City Ballet Company brings the good news of the gospel to people. We pray that God continues to bless their efforts.

If you want to learn more about this company, I wrote a blog post about them on website for The MAKE Collective, a network of missionary artists I lead. If you’d like to hear more stories like this, please subscribe to our newsletter. You can send an email to info [at] communityarts.jp.

This week I sat down with Byron Spradlin, president and CEO of Artist in Christian Testimony International. He heads almost 700 missionary artists serving around the world, what he calls “imaginative expression specialists,” people unusually wise at imaginative design and expression. He also leads the Lausanne Arts Movement, which is all about connecting artists around the world to encourage us in the role of artists and the arts for global missions.

He has been a huge encouragement and influence on me over the years, really a lot more than I can say. I first met Byron during my first few months in Japan when he was a keynote speaker for a conference, and I remember some of the things he talked about that day, even now. That began a friendship which has lasted all these years. Since then, we keep meeting up at different conferences and gatherings all over the world. I’ve been following him all these years as Artists in Christian Testimony has grown tremendously under his leadership, and the various talks he’s given and the things he’s written. So I asked him to sit down for this podcast and share some of these with you.

So, Byron, thank you so much for being here today.

ByronYou’re welcome. And I have been actually following you because I think you are one of the great imaginators and innovators of church planting and church effort on the planet today, particularly as an artistic kingdom servant. So deal with that, my friend.

RogerThank you. I mean, it is so exciting what God is doing around the world, and I feel privileged to be part of it.

But yeah, there’s so many things that I want to talk with you about today. And let’s go back to the first time that I heard you speak. You were talking about why is it that missionaries can be artists and why artists can be missionaries, that’s probably a better way to put it. What is the foundation that we find in the Bible for this kind of ministry?

ByronWell, you know, Roger, that’s a big question, and you got to keep me disciplined to make short answers here. But really the question would be, can we actually do God’s mission without artistically inclined people, without imaginative expression specialists?

RogerA lot of people would say we can.

BryonWell, they’re wrong. And having been a church planter and a senior pastor, a worship pastor, a youth pastor over many years, and been to 50 countries, and then studied it three or four times in seminary on different degrees and such. It is clear when we think about the purpose of the expansion of Christianity, we have to take into consideration the fact that God is the one who’s created the various cultures in the world. And these cultures are not the same. And therefore, we know that we need to have what I call indigenous Christian community formation in every tongue, tribe, and nation. And so the church will not look the same in Japan as it looks like in Fiji and such.

RogerYeah, but why do we need missionaries for that? I mean, there are nationals around the world who are artists, and they can be involved in church planting.

BryonEvery nation, tongue, and tribe is supposed to be sending missionaries. So the Fijians are supposed to be sending them, and the Japanese are supposed to be sending them, and the Israelis are supposed to be sending them and such. So that’s part of our ethnocentrism, our self-focus, as if Europe and the United States are the only ones who actually send missionaries. In 2021, you know that there are more Christians in the global south who are not white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. We are the minority, and that’s a good thing, to tell you the truth. And remember, Christianity is not a white European and North American faith. It’s a Middle Eastern Asian faith. So all that said, Christian ministry must reflect God’s image to be fully and truly Christian. And one dynamic of God’s image is creative. He is extremely creative. We fight about denominations, but denominations really are the creativity of God, where different folks are bringing different correctives to the worldwide body of Christ.

RogerWell, he made the heavens and earth in Genesis 1. But is there more to it than that?

ByronAbsolutely! Frankly, when we take a good look at, for example, the Hebrew expressions related to imaginal creativity and understand that the Hebrew culture was far more holistic than the modern, Western linear kinds of thinking, we realize that imaginal I almost like to call it not artistic expression, but imaginal expression. These kinds of expressions take what is observable and also take the revealed propositional word of God…remember, it was God’s idea to put the Bible into print media. Okay? He told Moses, write it down…

Roger“Print media.” Interesting.

ByronYeah. Why is that? Well, even though the Bible is not primarily prose and intellectual dialogue, it’s mostly narrative and wisdom literature, story, poetry, song, narrative. And there are parts that are instructional, but not the majority we draw from the revelation of God. I mean, we do have the Ten Commandments, but you can’t understand, for example, the Ten Commandments without imagining into the realities that the Ten Commandments explain. It’s not just don’t murder, don’t commit adultery. You have to imagine into the sanctity of life. And that’s not something that you’re making up. That’s a reality of the way God made human beings the sanctity of life and for the whole creation, for that matter. But he’s placed human beings at the pinnacle of that.

RogerOkay, but some examples of that would be what? Like, what were the prophets? Like, for example, I remember you talking about the most powerful one was Moses and the plagues that hit Egypt. And what is that? Well, that was a multimedia presentation. I’m like, what? And you went through a whole list.

ByronSure. Matter of fact, part of that list is, “In the beginning, God created.” We have the creation or creativity as the initial dynamic of God speaking out creation. And at the end, God will create a new heaven and a new earth, Revelation 21. Then we see immediately he sets up a garden. In creation, there was gardening. Adam and Eve didn’t just sit around. They tended the garden. I think they delighted in it. I’m sure they worked hard and all, but there was no negative dynamic to that. In Genesis Chapter 6 with Noah, we see carpentry. People may not have known what a boat was. I don’t think there had been rain exactly before that time. We get symbolic expression in Genesis 17, for example, circumcision. What was that all about? I can make jokes, but I won’t.

RogerThat’s probably best.

ByronIt was a symbol of God’s covenant with his people, right?

RogerVisual reminders of this covenant.

ByronBig time. We have culinary ministry in Genesis 18. Abraham entertained his three visitors to Sodom and Gomorrah, and they interacted over a meal. Well, some people would say, that’s just sort of like going out to lunch with each other. Stop. There is something deeply creative that expresses the transcendent reality of community, hospitality, sacrifice, honor, all of these kinds of dynamics that go on in presenting a meal to someone. It’s not just eating food. It is utilitarian. We got to eat food to live, but there’s something aesthetic about that. And there’s something deeply human, which is more than, “Here is hot dog. Eat hot dog. Put ketchup on it.” No, there’s all kinds of creativity that goes into it.

And isn’t it interesting. Dogs have instinct. Mooses have instinct. People have imagination. Whales don’t have imagination from what we can tell. They get from Alaska to Lahaina Maui in some phenomenal dynamic of instinct. It’s really amazing. But when we see it, we paint pictures and sing songs and develop sonar to trace their way and hopefully enter into creation care because we are the stewards of all of creation and need to take care of these beautiful mammals in the deep.

That’s a human phenomenon. Sometimes I’ve said human beings have never been satisfied to make a pot to carry their water. They have made the pot to carry their water, but then they’ve made it beautifully. They’ve painted it. That is a human dynamic, even in a fallen world. How about that? Amazing.

RogerAll right, so you’re talking about imagination. Yes, humans have that. Animals don’t. But how does that help us with the way that God has spoken to us?

ByronWell, I know you’re being the devil’s advocate here, but you’re being that because you and I have come out of a modernist, Western, Protestant, actually Christian community which has been so focused on rational intelligence and intellectual discourse as the two dynamics or the two things that are that are prime. I submit to you that though there are historical reasons why we have done that, moving to let the pendulum swing to those emphases is incomplete and ineffective, inadequately biblically communicating to human beings. And secondly, seeing created or nurtured human community in intimate involvement with the community of the Trinity. We’re not just setting up a philosophy here with a set of didactic or dogmatic principles. We’re dealing with life, life with God. So we need to understand that there are two other dynamics of intellect. There certainly is rational intellect, but there’s also imaginal intellect and emotional intellect. Right there, I’m sure some of your listeners are going, oh, man, this guy’s really a heretic. Well that’s because all of our life…in my background I’m an ordained Baptist minister. I’ve heard as you think, so you are. Well, I’ve known a lot of biblical Christians who think one way and then are disobedient another way.

It’s really what we love is who we are. Who we love. Matter of fact, James K. A. Smith and younger philosopher now at Calvin College, he’s been pointing out that what we worship really is what we love. So you figure out what you love and I often say what you admire, desire, pursue, and serve, and that will tell you what you really love and what you really worship. Now in that C.S. Lewis even says imagination is the organ of meaning. That is, you can be told something but you don’t know what it means unless you imagine into the realities that it is explaining. I mean we know this from scripture. “As the deer pants after the water so my heart pants after you.” That’s an age-old way of comparing something that is less understood or more difficult to understand with something that’s more familiar to understand. It’s a metaphor, and we have seen that you can’t understand facts without an imaginal dimension. Now, part of the problem is, I know I got to be careful not doing a lecture, but part of the problem that we see is that we think if we say something, if I explain A plus B equals C that we understand it, but we don’t.

RogerOkay, so let me stop you there. I want to ask you to give more examples of prophets using the arts to convey their message. You just mentioned poetry and song, all these different things, but the things that come to mind is that part in Isaiah where he walked through town with “buttocks bared.” I still can’t imagine. I’m not sure missionaries should do that nowadays…

ByronBut there are cultural ways of doing that same kind of outlandish thing to help people wrestle and be jolted into the realities of what God is speaking into their lives. Remember drama and theater? Jeremiah 13, the linen belt. Jeremiah 19, the clay jar incident. Jeremiah 27, making a yoke and wearing it around. Poor Jeremiah. Yeah, it was Jeremiah. He lay on his side…

RogerI think that’s Ezekiel.

ByronEzekiel, he had to lay on his side for, like, an incredible amount of time.

RogerYeah, he was going to use his own excrement to cook his food, and he’s like, no, let me use cow dung instead.

ByronYeah, that’s right.

RogerI’m just imagining missionaries doing this nowadays. It’s hard to imagine, but this is in the Old Testament. This is in the Scriptures of how prophets actually communicated God’s word.

ByronA lot of the missionaries who have broken into the preliterate societies have done exactly this. Look, we are not talking just about artsy fartsy strategy here. We are talking about the need to encourage nationals to have the validation of or the permission to create indigenous liturgy, indigenous expressions. What is liturgy anyway? It is metaphors and symbols and various kinds of activities, when infused in faith and arranged in a human engageable manner, somehow human beings step into the presence of God and touch his transcendent reality, which is a dynamic of mystery. It’s not just an intellectual exercise.

And we need artistic expressions. Everything in a worship service is an artistic expression, except maybe a dull sermon.

RogerYes, I agree with you. But also, why the role of missionaries? Why is it so important to send people over—all the money, support raising from the United States and from every country to every other country as you said before—

ByronSure.

RogerWon’t it just happen naturally? Why…

ByronApparently not. Number one, Jesus commanded it as you’re going, wherever you’re going, be making disciples. And then he said, this gospel shall be proclaimed to all of the nations, and then the end will come.

RogerSo that includes artists? We have to make disciples?

ByronYes, it does, quite frankly. We see that with Bezalel and Oholiab, first time the Holy Spirit actually filled individuals and gave them the ability to teach or we could put that “disciple.” Any teacher, particularly teachers of kindergarten through sixth grade, know that if you’re going to teach real understanding, you cannot just say it. These kids have to participate in it. You have to capture their imagination.

RogerAre you saying that that’s what God did with Israel and us?

ByronI teach worship in the Old Testament and one of the key things that I press in this deal is what in the world has got up to with the sacrificial system, 1500 years of a whole lot of life liturgies that just touch every aspect of life. Well, in that for 1500 years, he was trying to help people understand. Number one, he is in the middle of everything in life, every process of life. The way we use the bathroom, the way we have involvement with our spouse, the way we deal with our family, the way we wash our hands. These were not just religious things. These were how humans ought to live in a fallen system.

RogerWell, just the way you’re talking about this too. It’s so clear that God is Lord of culture, that he is intimately involved in how we interact with each other. So arts and culture, the way and the why it looks different in every single culture around the world is so exciting that God is intimately involved in that and how we interact with each other.

ByronAbsolutely. And maybe that might help in Japan. I mean, I’ve been going to Japan since 1966. I’ve been there maybe 15 times. And I’ve had the great privilege and honor of actually learning from many Japanese Christian leaders and have had the joy of explaining the role of worship in church growth and how if we can make that more indigenous, we will literally see God touch the hearts of people outside the church. Well, now, if that’s the case, and if worship is more than singing songs, God forbid that that’s your dull definition of what worship is. Worship is reverencing and responding to the person and the work of God 24/7. Worship is always personal. Sometimes it’s public in a gathered setting. And all the time it’s personal. And even when you’re in a gathered worshiping thing, you have come there to together with the body of Christ, reverence him and revere him and acknowledge who he is and rehearse his sovereignty and his supremacy and his primacy and his beauty and his love and slowness to anger and compassion and all of those things. And that’s why we celebrate communion oftentimes.

The Lord told us when we gathered together to rehearse the story of the gospel, not just to remember it in one sense, but to interact with the life-saving, soul-saving work of Jesus. We are not just satisfied because of God’s desire for us to go, oh, that’s nice. No, we need to write music like the Hallelujah Chorus. We need to write the greatest music in the world. We have the greatest paintings in the world, the greatest celebration in the world. Matter of fact, human community when it breaks out in song, whether they’re specialists or not. So part of the reason that we need artistically gifted people, people who are as the Hebrew words for craftsmen and artisans mean, people who are unusually wise at imaginative design or expression is wise.

Roger“Wise.” That’s an interesting word to use there. Not gifted, but wise.

ByronThat’s right. A matter of fact, you’ll see, whether it’s in the artisan and craftsman—there are 19 craft industries that we see in the scripture, in the Hebrew scriptures, the Old Testament and such, we see those plus musicians and singers. And if you look, these guys aren’t entertainers. These are part of the fabric of the community. Worshiping God and leading the community into the life of community, which is supposed to be in Israel’s history, centered around the reality of God’s love and faithfulness and compassion and restoration and such. That’s the meta-narrative. I mean, the Exodus and Passover and the Day of Atonement and all of these feasts, they demonstrate that God is in the middle of the community. They demonstrate that sacrifice is important and that sacrifice, where is it culminated? In Messiah. He is the Passover Lamb. He is the Great High Priest. That’s what the letter to the Hebrews in the New Testament is all about, trying to explain this and such, but who is best capable? I submit to you that God has given not a special class of people, but he’s given a specialized class of people, imagination specialists who are wise at imaginative design and expression, so that we take metaphors and symbols and human expressions or there are twelve human signal systems that every culture has, but they each have different meaning in that particular culture. So it’s not one size fits all, right? And we rearrange those in ways that provide environments like a celebration or a worship service or a pageant or a circumcision celebration or…

RogerAnd before we started this recording, you were telling me about “yatsar,” that Hebrew verb, because you were just talking about imagination quite a few times there, but what that means in the Hebrew scriptures I thought was fascinating.

ByronSure, now, the term “to imagine” is “yatsar.” The term, as I understand it’s pronunciation for “imagination” is “yetser.” You see these terms used 79 times in the scriptures, maybe six, seven, eight times…I’ve got to count it again, so I could be wrong…but seven, eight, nine times it’s translated “vain imaginations.” And we think of imagination as this dynamic where we think of something that isn’t true and pretend that it is true. So idolatry, for example. That is a vain imagination. That’s a good example of it. We have thought something up that isn’t true, and we have placed faith in it as if it were true. But most of the usages of imagination or to imagine are in the context of reality, that is, it means to form in your mind before you fashion it in time and place.

Protestant Christians particularly haven’t liked that idea since the 1500s when the Reformation began. And these Protestants wanted the word of God in the vernacular, which is good. It’s essential to say we want that today. And they were sick and tired of religious humanism, religion without Jesus. And so they wanted to expound the word of God and understand it more deeply. And that is very good. We should not back off on that at all. But to understand how human beings actually learn and embrace, inculcate, digest, assimilate, that psychomotor reality of interaction with life and with others. That’s not just a formula, there’s a mystery in there. And part of it is we have to imagine it.

RogerBut what you were saying before, too, is that imagination is not something that’s just unique to humans, but that has come from something. It’s part of the image of God. And you were even referring to a scripture passage that said…

ByronFor example, Isaiah 26:3. In the King James it says, “He is kept in perfect peace whose mind is staid on thee.” It’s not the Hebrew word for mind. It’s the Hebrew word for imagination. But we don’t like that word in English, so we don’t translate it that way. Actually, I checked it in Japanese too…

Anyway, we generally translate imagination in scripture as mind, form, or fashion. But those three words do not catch the fullness of the edgelessness, the bigness of what God has given human beings to enter into interaction with the infinite realities of his nature. As J.I. Packer said, the infinite perfections of who he is, his attributes. We have to have a design feature that allows us to move into the bigness and the greatness, which we will never exhaust. Paul said, “Oh, the depths of the riches, both of the knowledge and the wisdom of God. How unsearchable they are. How unfathomable they are.” And then he goes on, “Who has known his mind? Who’s become his counselor? Who has done anything to obligate him to pay that person back? No, all things are from him and through him, and go back to him, to him be the glory forever.” That doxology, which happens to be a first-century hymn, by the way, that he just lifted out of the culture, he didn’t make that up. It was a hymn that was being sung. It’s a didactic hymn that he plunked in the middle of this letter to the Roman Church and to others. He’s coming off of having explained this phenomenal reality of the atoning work of Christ.

RogerLet me just go back to the scripture passage you just quoted. It says that God basically had imagination. So it can’t be a bad thing.