Eve Smith's Blog, page 3

March 25, 2020

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM LIFE IN LOCKDOWN?

With the UK government introducing the most stringent social distancing measures in this country’s history in an attempt to curb the spread of COVID-19, we are embarking on an unprecedented social experiment as not only the UK, but multiple countries around the world, adapt to life in lockdown.

The vast majority of us will have to stay at home, either on our own, or with immediate family, for an indefinite period. Current UK restrictions mean our isolation will last between three and twelve weeks, depending on whether we are one of the 8.8 million over-seventies, or whether we are pregnant or have an underlying health condition, which accounts for another 21 million people at least.

What’s more, it is highly likely that three weeks will turn into six, and twelve into twenty-four.

So how will we fare as a society, distancing ourselves from our neighbours, our extended family and friends? How will we cope without going to work or the pub, unable to meet up with mates or parents, forbidden to go for a coffee or work out at the gym?

No one really knows what the impact of enforced quarantine with family members over a prolonged period might be. Just imagine Xmas, but three or twelve times as long.

After the festive period, the relationship counselling charity Relate get around a 40% spike in calls. The New Year brings a higher number of divorce petitions than at any other time of year. So add to that financial uncertainty, sickness, restricted availability of basic household items and food and you have a powerful recipe for the worst kind of cabin fever. Families will be under huge emotional strain.

It may sound trite, but we really will have to dig deep to find a touch more tolerance for each other. Amidst the upturned routines, the mounting uncertainties and the enforced ‘togetherness’, we’ll need to take a collective deep breath, slow down a little and try to stay calm.

Even when the wine’s run out and your teenager’s still raging about how slow the WiFi is, the dog’s barfed on the carpet because someone spilled chilli nuts on the sofa, and your toddler’s just wedged a spoon in the toaster, spare a thought for those that have no family to rail against.

For those that are sitting out their twelve or twenty weeks all on their own.

If there is one good thing that may come out of this experience (and I hope there will be many), it is a better understanding of the effects of loneliness and social isolation on our wellbeing, and a greater empathy for those who have to deal with these feelings every day.

For the first time, all of us no longer have a choice when it comes to socialising, beyond our immediate family. Direct contact with others is prohibited, whether it be through work, leisure or sport. Many of us will be self-isolating, or separated from relatives and loved ones who are self-isolating. But at least this isolation is temporary.

The most terrible poverty is loneliness, and the feeling of being unloved.

— Mother Teresa

Age UK conduct a lot of research into the impacts of social isolation and loneliness, both of which can affect anyone at any point in their lives. They define social isolation as an objective measure of the number of contacts that people have. It is the quantity of connections that counts, the physical connection or separation, and what people are comfortable with can vary significantly.

Loneliness, on the other hand, is a subjective feeling about the gap between a person’s desired levels of social contact and their actual level of social contact. Loneliness is about the perceived quality, not quantity of relationships. It is an emotional state of feeling separated or alone.

Social isolation can be remedied by increasing the number of people a person is in contact with. Loneliness, on the other hand, is much harder to overcome, and takes time.

It is not simply a matter of choice. Or law. And it can have significant effects on our physical and mental health, with strong links to anxiety and depression.

It will come as no surprise that the elderly are amongst the worst affected. Age UK estimates there are 1.2 million chronically lonely people in the UK. More than a third of elderly people reported being overwhelmed by loneliness. But it is not just older people who are lonely.

The findings of the Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness reported that 9 million Britons suffer from loneliness—14% of the population.

Amongst people living with disabilities, half reported feelings of loneliness at least once a day. Fifty-eight per cent of refugees and migrants in London said that loneliness and isolation presented their biggest challenges. Eight out of ten caregivers reported feelings of isolation as a result of looking after a loved one and, incredibly, 52% of parents.

This is before the lockdown.

For many, technology will come to the rescue and keep people in touch with their friends and loved ones, via smartphones and apps. But for others, often the most vulnerable, they have neither the resources, the contacts nor the expertise to use such devices.

Nearly 4 million people over sixty-five have never used the internet. Technology will not help them.

According to Age UK, 3.9 million over-sixty-five’s rely on television as their main form of company and over half of all people aged seventy-five plus live alone.

Amongst these already isolated people, the social habits they may have cultivated around shopping or church visits, community allotments or U3A meetings can now no longer take place.

The closure of libraries, churches and community centres, the cancellation of drop in sessions and membership events, exacerbate their isolation. No more congregations or coffee, no more WI or garden club, no more chats in the line for the till.

Which is why the community help initiatives being set up all over the country are so vital. Neighbours looking out for each other, dropping leaflets offering help, fetching shopping or medication, ringing up to check they’re OK.

In my speculative thriller, The Waiting Rooms, the over-seventies are permanently isolated. Set after an antibiotic crisis, in a world where multiple pandemics raged, emergency legislation prohibits the prescription of new antibiotics to anyone over seventy, in a last ditch attempt to keep resistance at bay. Society sacrifices the elderly for the health of the young.

This legislation results in a permanent state of vulnerability for the elderly which not only threatens their lives but which also, inevitably, leads to social exclusion. As one of the characters, Lily, says: ‘It’s like we’re living in some kind of ageist apartheid.’

I am very pleased to see that in real life, when put to the test, our society has not made such an abhorrent choice, and that we are doing the exact opposite. The whole purpose of our enforced isolation is to protect the vulnerable and the elderly. We are sacrificing our social contact to keep them safe.

But, when we come out the other side, we need to remember what social isolation felt like.

The community initiatives and renewed neighbourliness that COVID-19 inspired do not need to fade. This could be a positive legacy of these extraordinary times: to ensure that what was a temporary lockdown for us does not remain a permanent lockdown for the lonely.

E-book out 9th May: Pre-Order

Subscribe

Sign up with your email address to receive news and updates.

Email Address

Sign Up

We respect your privacy.

Thank you!

What's New? RSS

March 3, 2020

CORONAVIRUS AND “THE SILENT PANDEMIC”

COVID-19 is bothering me a lot, right now. It’s not just the fact that we are teetering on the edge of a worldwide pandemic, with case numbers exceeding 90,000, deaths escalating above 3000, and WHO moving the global threat level to “very high” for both spread and impact.

Or that, according to the OECD, coronavirus will present the global economy with its greatest danger since the 2008 financial crisis.

It’s the realisation that an alarming number of scenes from a speculative thriller I finished writing several months ago appear to be coming true.

Obsessive handwashing and hygiene; masks worn in public places. Handshaking being a thing of the past. Emergency hospitals and quarantine. Restrictions on travel and large gatherings. Stockpiling. Isolation of the elderly, as ‘social distancing’ and ageism take hold. Political ‘scapegoating’ by the far right.

My novel, The Waiting Rooms, isn’t about a viral pandemic. It dramatises what Mariangela Simao from the World Health Organisation calls “the silent pandemic”, because it spreads largely unnoticed: antimicrobial resistance. Whilst my book is set in a fictional world, in the advent and aftermath of an antibiotic crisis, the links between these real public health emergencies are unsettling.

Let’s look at some numbers. Deaths from COVID-19, as of 3rd March are 3,110. The lowest global death rate estimated was about 1% of cases, which doesn’t sound much, but is actually ten times the rate of seasonal flu. And WHO just updated their global mortality estimate to 3.4%.

Deaths from flu vary widely each year depending on the influenza strain, but global numbers, according to WHO, range from 290,000 to 650,000.

We don’t know the exact number of deaths from antibiotic-resistant infections, because they are not consistently reported, but WHO estimates there are at least 700,000 deaths each year. “At least” suggests it is a conservative projection. Resistant strains of tuberculosis alone account for almost a quarter of a million fatalities.

So why isn’t antibiotic resistance making the headlines?

The truth is, sometimes it does. And the fact that people are more concerned about COVID-19 than the flu or antibiotic resistance is no surprise. This coronavirus is new and spreads fast, it has no vaccine or cure. There are still a lot of unknowns.

Flu is an annual event; we’ve become accustomed to it even though its numbers dwarf COVID-19. And antimicrobial resistance? Well, it has many faces, depending on which resistant infection presents: TB, MRSA, C-Diff, pneumonia: take your pick. So it slips under the radar.

Which is why WHO have dubbed it “the silent pandemic”.

So how does all this relate to COVID-19?

A World Bank report called Pandemics: Risks, Impacts, Mitigation says antibiotic resistance is a threat that "could amplify mortality during pandemics of bacterial diseases such as tuberculosis and cholera and even viral diseases, especially for influenza, in which a significant proportion of deaths is often the result of bacterial pneumonia coinfections."

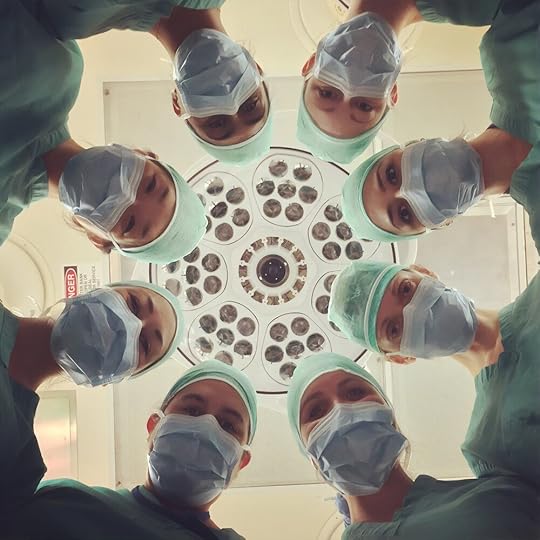

This is exactly the case for the current coronavirus. Most of the people who have died either had pre-existing conditions, like autoimmune diseases, or they developed secondary infections, such as severe pneumonia. These secondary infections can become much more prevalent once our immune systems are busy fighting a virus. As virologist Christine Tait-Burkard of the University of Edinburgh says: “That’s why the important thing is to treat people for comorbidities and give them antibiotics to stop bacterial infections taking hold.”

But what if there aren’t any effective antibiotics to stop them taking hold?

The Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy reported last year that, in the event of a significant influenza pandemic, secondary infections caused by prevalent pan-drug resistant bacteria could be catastrophic. But their report doesn’t seem to be having much impact on America’s farming methods, which still use vast quantities of antibiotics. 80% of antibiotics in the US are used on animals.

The uncomfortable fact is that antimicrobial resistance will increase both the frequency and the severity of pandemics.

So where do we go from here?

The good news about coronavirus (and there is, at least, some good news) is that many of the precautionary measures being adopted, such as washing our hands and good hygiene in the home and workplace, will help in the battle against antibiotic resistance, too.

But here’s the thing: even on handwashing, people are still confused. Shops have been running out of antibacterial hand gel as people rush out to stockpile it, despite the fact it is totally ineffective against COVID-19 because coronavirus is, guess what? A virus. Not a bacterial strain. A distinction which still appears to be largely misunderstood.

Such behaviour is underpinned by research that states two out of three Europeans are unaware that antibiotics are ineffective against viruses. When it comes to educating people about the appropriate use of antibiotics as a precious resource, we still have a long way to go.

So please, stick to the alcohol-based gels and good old-fashioned soap! And keep washing those hands, even when all this is over.

I’ve seen enough scenes from The Waiting Rooms become our new reality. I don’t want to see any more.

January 24, 2020

PROOFS, PANDEMICS, AND POSITIVES

Today, for the first time, I will actually get my hands around a printed copy of The Waiting Rooms.

I can’t tell you how exciting that is, for a debut author. It is the ultimate evidence that what you have written is actually going to make it into the hands of readers. It’s no coincidence that it’s called a proof.

This early print run will now find its way onto the desks of bloggers, authors, overseas publishers and members of the press. If I’m lucky, they will like it. The subject of antibiotic resistance is certainly timely. Then the next stage of this book’s journey will begin.

With the advent of the latest coronavirus, many of us are contemplating medical disasters and disease closer to home. While China locks down its cities and attempts to build a new hospital in five days, the US has already confirmed its first two cases, and Public Health England says that cases in the UK are ‘highly likely’. The international community are now agonising over lockdowns of their own.

I went to two rather terrifying talks by epidemiologists last year. (Yes, I do have an unhealthy interest in death and disease.) They made it clear that it was only a matter of time before the next SARS or MERS would emerge: both were coronaviruses and neither had a vaccine or a cure. Fortunately, the Wuhan coronavirus, as it’s being dubbed, appears to have a much lower mortality rate than SARS. So far.

While this outbreak was gathering pace, important discussions were taking place at the World Economic Forum this week. In between the political and trade wranglings, leaders convened on critical global issues, like climate change. And antimicrobial resistance.

In one such panel, industry leaders, government officials, academics and foundations discussed the broken business model for antibiotics. Which is just as well, as two reports, just released by the World Health Organisation on the number of viable new antibiotics currently in development, make grim reading.

Imagine if infections we regard as commonplace became untreatable: skin infections, gut infections, respiratory infections. It would be the equivalent of multiple SARS pandemics breaking out in every country in the world.

Never has the threat of antimicrobial resistance been more immediate and the need for solutions more urgent.

— Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of WHO

The WHO director general went on to say that efforts to discover new antibiotics were “insufficient to tackle the challenge of increasing emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance”.

The Davos panel made no bones about it: antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the biggest public health threats the world is facing, and drug-resistant infections have the potential to undermine all that has been achieved in modern medicine. And yet, no new classes of antibiotics have been developed since the 1980s.

But amongst this bleak assessment is hope. I was struck by one of the panellist’s comments:

The climate crisis is a huge problem that we don’t really know how to solve. Antimicrobial resistance is a huge problem that we know how to solve, the only problem is that the market model is broken.

— Lars Sorensen, Chairman of the Novo Nordisk Foundation

And these experts know how to crack it. There are innovative funding models for research and development being trialled in different markets right now, including in the UK. The issue is, persuading other governments and corporations to come on board, when they have a host of short term priorities that they consider more pressing.

As we have seen with climate change, the complexity and long-term nature of these challenges often lead to inertia. And that’s where we come in. If voters care about an issue enough, politicians will care, too. AMR needs public engagement. It needs a Greta. So we can push this one right to the top of the to-do list, where it belongs.

November 22, 2019

FROM SNOWSTORMS TO DYSTOPIA

Well, it’s finally happened. I can hardly believe it. My debut novel, The Waiting Rooms, will be published next July.

Woohoo! It still feels a little unreal. As if I’ve just been notified that I’ve won the lottery: I’m not sure if it’s some kind of phishing scam or joke. Like most new writers, the journey to publication has not been straightforward. But it has trained me well in the art of resilience.

You could say I’ve come full circle. As a child I loved writing stories and boy, did I write a lot. I remember one about a rather fierce talking dog from another planet. Even back then, I favoured the dystopian. My mother would tidy up the pages I’d left scattered around the house and post a few off to unsuspecting relatives, softening the blow with a painting or two. The rest mysteriously disappeared.

My viewing habits as an early teen cultivated my love for the darker genres. Unbeknownst to my parents, every Friday I’d sneak into my sister’s bedroom to watch the Hammer House of Horror late-night double bill. These black-and-white classics were barely visible on the portable TV’s twelve inch display, compounded by the aerial, which looked like a circular coat hanger and was about as effective. You had to twiddle with it constantly to dispel the snowstorm fuzzing up the screen.

Another weekly ritual was Anglia TV’s adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected. My sister and I were hooked from the opening titles: flashes of tarot cards and roulette wheels with an alluring Bond-like silhouette of a woman dancing in flames to music from a fairground carousel. That’s when I realised the difference between those early horror films and these stories. Horror films frightened me. Tales of the Unexpected terrified me. With horror, I had a mental fire exit: such things could never happen. There was no such escape from Roald Dahl. He planted his stories firmly in the familiar, lulling you into a false sense of security before delivering his macabre twists. No need for blood or gore. Those tales haunted me.

Author Eve Smith with her faithful writing companion, Lola.

So, a few decades later, when I took to the page once more, it was those kinds of stories I wanted to write: the ones that stay with you long after you finish them. Mine may feel a touch more dystopian than Tales of the Unexpected, but, these days, you don’t have to wander far to find nightmarish worlds very close to our own. Like the excellent series Black Mirror, my alternative realities deal in the familiar, the all-too possible. As Margaret Atwood said of her prophetic fiction, I truly hope they never happen. But I do hope the discomfort and dilemmas they foment survive long after the tweets and the headlines have faded. Because that is the power of storytelling.

ALL ABOUT EVE

Author Eve Smith with her faithful writing companion, Lola

I write speculative fiction, which basically means ‘what if …?’ stories: curious slants on the familiar, mainly about the things that scare me. I attribute this love of all things dark and dystopian to a childhood watching Tales of the Unexpected and black-and-white Edgar Allen Poe double bills.

In this world of questionable facts, stats and news, I believe storytelling is more important than ever to engage people in real life issues, in meaningful ways.

Set twenty years after an antibiotic crisis, my debut novel The Waiting Rooms was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize First Novel Award. My flash fiction has been shortlisted for the Bath Flash Fiction Award and highly commended for The Brighton Prize.

My previous job as COO of an environmental charity took me to research projects across Asia, Africa and the Americas, and I have an ongoing passion for wild creatures, wild science and far-flung places. A Modern Languages graduate from Oxford, I returned to Oxfordshire fifteen years ago to set up home with my husband.

When I’m not writing I’m chasing across fields after my dog, attempting to organise myself and my family or off exploring somewhere new.