Allan Kelly's Blog, page 7

February 1, 2024

Big and small, resolving contradition

Have I been confusing you? Have I been contradictory? Remember my blog from two weeks back – Fixing agile failure: collaboration over micro-management? Where I talked about the evils of micro-management and working towards “the bigger thing.” Then, last week, I republished my classic Diseconomies of Scale where I argue for working in the small. Small or big?

Actually, my contradiction goes back further than that. It is actually lurking in Continuous Digital were I also discuss “higher purpose” and also argue for diseconomies of scale a few chapters later. There is a logic here, let me explain.

When it comes to work, work flow, and especially software development there is merit in working in the small and optimising processes to do lots of small: small stories, small tasks, small updates, small releases, and so on. Not only can this be very efficient – because of diseconomies – but it is also a good way to debug a process. In the first instance it is easier to see problems and then it is easier to fix them.

However, if you are on the receiving end of this it can be very dispiriting. It becomes what people call “micro management” and that is what I was railing against two weeks ago. To counter this it is important to include everyone doing the work in deciding what the work is, give everyone a voice and together work to make things better.

Yet, the opposite is also true: for every micro-manager out there taking far too much interest in work there is another manager who is not interested in the work enough to consider priorities, give feedback or help remove obstacles. For these people all those small pieces of work seem like trivia and they wonder why anyone thinks they are worth their time?

When working in the small its too easy to get lost in the small – think of all those backlogs stuffed with hundreds of small stories which nobody seems to be interested in. What is needed is something bigger: a goal, an objective, a mission, a BHAG, MTP… what I like to call a Higher Purpose.

Put the three ideas together now: work in the small, higher purpose and teams.

There is a higher purpose, some kind of goal your team is working towards, perhaps there is more than one goal, they may be nested inside one another. The team move towards that goal in very small steps by operating a machine which is very effective at doing small things: do something, test, confirm, advance and repeat. These two opposites are reconciled by the team in the middle: it is the team which shares the goal, decides what to do next and moves towards it. The team has authority to pursue the goal in the best way they can.

In this model there is even space for managers: helping set the largest goals, working as the unblocker on the team, giving feedback in the team and outside, working to improve the machine’s efficiency, etc. Distributing authority and pushing it down to the lowest level doesn’t remove managers, like so much else it does make problems with it more visible.

Working in the small is only possible if there is some larger, overarching, goal to be worked towards. So although it can seem these ideas are contradictory the two ideas are ultimately one.

The post Big and small, resolving contradition first appeared on Allan Kelly.

January 24, 2024

Software has diseconomies of scale – not economies of scale

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

John Maynard Keynes

Most of you are not only familiar with the idea of economies of scale but you expect economies of scale even if you don’t know any ecoomics. Much of our market economy operates on the assumption that when you buy/spend more you get more per unit of spending.

At some stage in our education — even if you never studied economics or operational research — you have assimilated the idea that if Henry Ford builds 1,000,000 identical, black, cars and sells 1 million cars, than each car will cost less than if Henry Ford manufactures one car, sells one car, builds another very similar car, sells that car and thus continues. The net result is that Henry Ford produces cars more cheaply and sells more cars more cheaply, so buyers benefit.

(Indeed the idea and history of mass production and economies of scale are intertwined. Today I’m not discussing mass production, I’m talking Economies of Scale.)

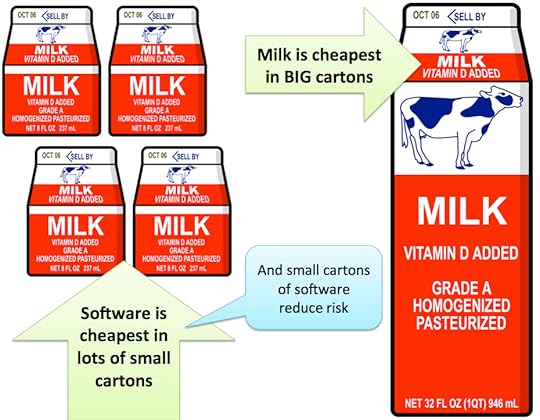

Software is cheaper in small cartons, and less risky too

Software is cheaper in small cartons, and less risky tooYou expect that if you go to your local supermarket to buy milk then buying one large carton of milk — say 4 pints in one go — will be cheaper than buying 4 cartons of milk each holding one pint of milk.

Back in October 2015 I put this theory to a test in my local Sainsbury’s, here is the proof:

Milk is cheaper in larger cartons1 pint of milk costs 49p (marginal cost of one more pint 49p)2 pints of milk cost 85p, or 42.5p per pint (marginal cost of one more pint 36p)4 pints of milk cost £1, or 25p per pint (marginal cost of one more pint 7.5p) (January 2024: the same quantity of milk in the same store now sells for £1.50)

Milk is cheaper in larger cartons1 pint of milk costs 49p (marginal cost of one more pint 49p)2 pints of milk cost 85p, or 42.5p per pint (marginal cost of one more pint 36p)4 pints of milk cost £1, or 25p per pint (marginal cost of one more pint 7.5p) (January 2024: the same quantity of milk in the same store now sells for £1.50)(The UK is a proudly bi-measurement country. Countries like Canada and Switzerland teach their people to speak two languages. In the UK we teach our people to use two systems of measurement!)

So ingrained is this idea that when it supermarkets don’t charge less for buying more complaints are made (see The Guardian.)

Buying milk from Sainsbury’s isn’t just about the milk: Sainsbury’s needs the store, the store needs staffing, it needs products to sell, and they need to get me into the store. All that costs the same for one pint as for four. Thats why the marginal costs fall.

Economies of scale are often cited as the reason for corporate mergers: to extract concessions from suppliers, to manufacture more items for lower overall costs. Purchasing departments expect economies of scale.

But…. and this is a big BUT…. get ready….

Software development does not have economies of scale.

In all sorts of ways software development has diseconomies of scale.

If software was sold by the pint then a four pint carton of software would not just cost four times the price of a one pint carton it would cost far far more.

The diseconomies are all around us:

Small teams frequently outperform large teams, five people working as a tight team will be far more productive per person than a team of 50, or even 15. (The Quattro Pro development team in the early 1990s is probably the best documented example of this.)

The more lines of code a piece of software has the more difficult it is to add an enhancement or fix a bug. Putting is fix into a system with 1 million lines can easily be more than 10 times harder than fixing a system with 100,000 lines.

Projects which set out to be BIG have far higher costs and lower productivity (per unit of deliverable) than small systems. (Capers Jones’ 2008 book contains some tables of productivity per function point which illustrate this. It is worth noting that the biggest systems are usually military and they have an atrocious productivity rate — an F35 or A400 anyone?)

Waiting longer — and probably writing more code — before you ask for feedback or user validation causes more problems than asking for it sooner when the product is smaller.

The examples could go on.

But the other thing is: working in the large increases risk.

Suppose 100ml of milk is off. If the 100ml is in one small carton then you have lost 1 pint of milk. If the 100ml is in a 4 pint carton you have lost 4 pints.

Suppose your developers write one bug a year which will slip through test and crash users’ machines. Suppose you know this, so in an effort to catch the bug you do more testing. In order to keep costs low on testing you need to test more software, so you do a bigger release with more changes — economies of scale thinking. That actually makes the testing harder but…

Suppose you do one release a year. That release blue screens the machine. The user now sees every release you do crashes their machine. 100% of your releases screw up.

If instead you release weekly, one release a year still crashes the machine but the user sees 51 releases a year which don’t. Less than 2% of your releases screw up.

Yes I’m talking about batch size. Software development works best in small batch sizes. (Don Reinertsen has some figures on batch size in The Principles of Product Development Flow which also support the diseconomies of scale argument.)

Ok, there are a few places where software development does exhibit economies of scale but on most occasions diseconomies of scale are the norm.

This happens because each time you add to software work the marginal cost per unit increases:

Add a fourth team member to a team of three and the communication paths increase from 3 to 6.

Add one feature to a release and you have one feature to test, add two features and you have 3 tests to run: two features to test plus the interaction between the two.

In part this is because human minds can only hold so much complexity. As the complexity increases (more changes, more code) our cognitive load increases, we slow down, we make mistakes, we take longer.

(Economies of scope and specialisation are also closely related to economies of scale and again on the whole, software development has diseconomies of scope (be more specific).)

However be careful: once the software is developed then economies of scale are rampant. The world switches. Software which has been built probably exhibits more economies of scale than any other product known to man. (In economic terms the marginal cost of producing the first instance are extremely high but the marginal costs of producing an identical copy (production) is so close to zero as to be zero, Ctrl-C Ctrl-V.)

What does this all mean?

Firstly you need to rewire your brain, almost everyone in the advanced world has been brought up with economies of scale since school. You need to start thinking diseconomies of scale.

Second, whenever faced with a problem where you feel the urge to go bigger run in the opposite direction, go smaller.

Third, take each and every opportunity to go small.

Four, get good at working in the small, optimise your processes, tools, approaches to do lots of small things rather than a few big things.

Fifth, and this is the killer: know that most people don’t get this at all. In fact it’s worse…

In any existing organization, particularly a large corporation, the majority of people who make decisions are out and out economies of scale believers. They expect that going big is cheaper than going small and they force this view on others — especially software technology people. (Hence Large companies trying to be Agile remind me of middle aged men buying sports cars.)

Many of these people got to where they are today because of economies of scale, many of these companies exist because of economies of scale; if they are good at economies of scale they are good at doing what they do.

But in the world of software development this mindset is a recipe for failure and under performance. The conflict between economies of scale thinking and diseconomies of scale working will create tension and conflict.

Originally posted in October 2015 and can also be found in Continuous Digital.

To be the first to know of updates and special offers subscribe — and get Continuous Digital for free.

The post Software has diseconomies of scale – not economies of scale first appeared on Allan Kelly.

January 15, 2024

Fixing agile failure: collaboration over micro-management

I’ve said it before, and I’m sure I’ll say it again: “the agile toolset can be used for good or evil”. Tools such as visual work tracking, work breakdown cards and stand-ups are great for helping teams take more control over their own work (self-organization). But in the hands of someone who doesn’t respect the team, or has micro-management tendencies, those same tools can be weaponised against the team.

Put it this way, what evil pointed-headed boss wouldn’t want the whole team standing up at 9am explaining why they should still be employed?

In fact, I’m starting to suspect that the toolset is being used more often as a team disabler than a team enabler. Why do I suspect this?

Reason 1: the increasing number of voices I hear criticising agile working. Look more closely and you find people don’t like being asked to do micro-tasks, or being asked to detail their work at a really fine-grained level, then having it pinned up on a visual board where their work, or lack of, is public.

Reason 2: someone I know well is pulling their hair out because at their office, far away from software development, one of the managers writes new task cards and inserts them on to the tracking board for others to do, hourly. Those on the receiving end know nothing about these cards until they appear with their name on them.

I think this is another case of “we shape our tools and then our tools shape us.” Many of the electronic work management tools originally built for agile are being marketed and deployed more widely now. The managers buying these tools don’t appreciate the philosophy behind agile and see these tools as simply work assignment and tracking mechanisms. Not only do such people not understand how agile meant these tools to be used they don’t even know the word agile or have a very superficial understanding.

When work happens like this I’m not surprised that workers are upset and demoralised. It isn’t meant to be this way. If I was told this was the way we should work, and then told it was called “agile” I would hate agile too.

So whats missing? How do we fix this?

First, simply looking at small tasks is wrong: there needs to be a sense of the bigger thing. Understand the overall objective and the you might come up with a different set of tasks.

Traditionally in agile we want lots of small work items because a) detailed break down shows we understand what needs to be done, b) creating a breakdown with others harnesses many people’s thinking while building shared understanding, c) we can see work flowing through the system and when it gets stuck collectively help.

So having lots of small work items is a good thing, except, when the bigger thing they are building towards is missing and…

Second, it is essential teams members are involved with creating the work items. Having one superior brain create all the small work items for others to do (and then assign them out) might be efficient in terms of creating all the small work items but it undermines collaboration, it demotivates workers and, worst of all, misses the opportunity to bring many minds to bear on the problem and solution.

The third thing which cuts through both of these is simple collaboration. When workers are given small work items, and not given a say in what those items are, then collaboration is undermined. When all workers are involved in designing the work, and understanding the bigger goals, then everyone is enrolled and collaboration is powerful.

Fixing this is relatively easy but it means making time to do it: get everyone together, talk about the goals for the next period (day, week, sprint, whatever) and collectively decide what needs doing and share these work items. Call it a planning meeting.

The problem is: such a meeting takes time, it might also require you to physically get people together. The payback is that your workers will be more motivated, they will understand the work better and are ready to work, they will be primed to collaborate and ready to help unblock one another. It is another case of a taking time upfront to make later work better.

The post Fixing agile failure: collaboration over micro-management first appeared on Allan Kelly.

December 12, 2023

Why I don’t like pre-work (planning, designing, budgetting)

You might have noticed in my writing that I have a tendency to rubbish the “Before you do Z you must do Y” type argument. Pre-work. Work you should do before you do the actual work. Planning, designing, budgeting, that sort of thing.

Why am I such a naysayer?

Partly this comes from a feeling that given any challenge it is always possible to say “You should have done something before now” – “You missed a step” – “If you had done what you were supposed to do you wouldn’t have this problem.” Most problems would be solve already, or would never have occurred, if someone had done the necessary pre-work.

There is always something you should have done sooner but, without a time machine, that isn’t very useful advice. Follow this line of reasoning and before you know it there is a great big process of steps to be done. Most people don’t have the discipline, or training, to follow such processes and mistakes get made. The bigger the process you have the more likely it is to go wrong.

However, quite often, the thing you should have done can still be done. Maybe you didn’t take time to ask customers what they actually wanted before you started building but you could still go and ask. Sure it might mean you have to undo something (worst case: throw it away) but at least you stop making the wrong thing bigger. Doing things out of order may well make for more work, and more cost, but it is still better than not doing it at all.

Some of my dislike simply comes from my preference. Like so many other people, I like to get on and do something: why sit around talking about something when we should be doing! I’m not alone in that. While I might be wrong to rush to action it is also wrong to spend so long talking that you never do it, “paralysis by analysis.” Add to that, when someone is motivated to do something its good to get on and do something, build on the motivation. Saying “Hold on, before you …” may mean the moment is missed, the enthusiasm and motivation is lost.

So, although there is a risk in charging in there is also a risk in not acting.

Of all the things that you might do to make work easier once you start “properly” some will be essential and some till not. Some pre-work just seems like a good idea. One way to determine what is essential is to get on with the work and do the essentially when get to them. Just-in-time.

For example, before you begin a piece of work, it is a really good idea to talk about the acceptance criteria – “what does success look like?” If you pick up a piece of work and find that there are no acceptance criteria you could say “Sorry, I can’t do this, someone needs to set criteria and then I’ll do it” or you could go and find the right person and have the conversation there and then. When some essential pre-work is missing it becomes job number 1 to do when you do do the work.

Finally, another reason I dislike pre-work is the way it interacts with money.

There are those who consider pre-work unnecessary and will not allocate money to do it (“Software design costs time and money, just code.”) If instead of seeing pre-work as distinct from simply doing the work then it is all part of the same thing: rather than allocate a few hours for design weeks before you code simply do the design for the first few hours of the work. That way, making the pre-work into a just-in-time activity you remove the possibility the work is cancelled or that it changes.

My other gripe with money is the way, particularly in a project setting, pre-work is accounted for differently. You see this in project organizations where nobody is allowed to do anything practical until the budget (and a budget code) is created for the work. But the work that happens before then seems to be done for free: there is an unlimited budget for planning work which might be done.

Again, rather than see the pre-work – planning, budgeting, designing, etc. – as something distinct that happens before the work itself just make it part of the work, and preferably do it first.

Ultimately, I’m not out to bad pre-work, I can see that it is valuable and I can see that done in advance it can add more value. Its just that you can’t guarantee it is done, if we build a system that doesn’t depend on pre-work being done first, then the system is more robust.

The post Why I don’t like pre-work (planning, designing, budgetting) first appeared on Allan Kelly.

July 18, 2023

3 ideas until you nuke the backlog

Read the full post over on Medium.

The post 3 ideas until you nuke the backlog first appeared on Allan Kelly.

The post 3 ideas until you nuke the backlog appeared first on Allan Kelly.

July 13, 2023

Nuke your backlog?

I’ve written a post to accompany “Honey, I shrunk the backlog” over on Medium, Nuke the backlog.

The post Nuke your backlog? first appeared on Allan Kelly.

The post Nuke your backlog? appeared first on Allan Kelly.

July 11, 2023

Comments, off, sorry

I’ve always enjoyed the comments people leave on this blog – even when people disagree.

Unfortunately, for the last few months the vast majority of comments I am receiving are spam – people trying to add links to their own websites and such. The same comments are made again and again, sometimes a dozen in a day.

So, with a heavy heart I’ve switched comments off for now. I’m happy to receive your comments, please e-mail me allan AT allankelly.net.

Of course, as I’m experimenting with Medium at the moment most of my content is appearing there and you can comment there. So please follow me over there.

The post Comments, off, sorry first appeared on Allan Kelly.

The post Comments, off, sorry appeared first on Allan Kelly.

July 5, 2023

OKRs create strategy alignment but not in the way you think they do

Flat 3d isometric business people came from different way but have same target. Business team and target concept.

Flat 3d isometric business people came from different way but have same target. Business team and target concept.One of the claims made of OKRs is they solve the problem of alignment, strategic alignment specifically. So, anyone reading Pull don’t push OKRs post might be wondering how this can be. I’m sure many people will ask how alignment can be achieved without some master plan and planner?

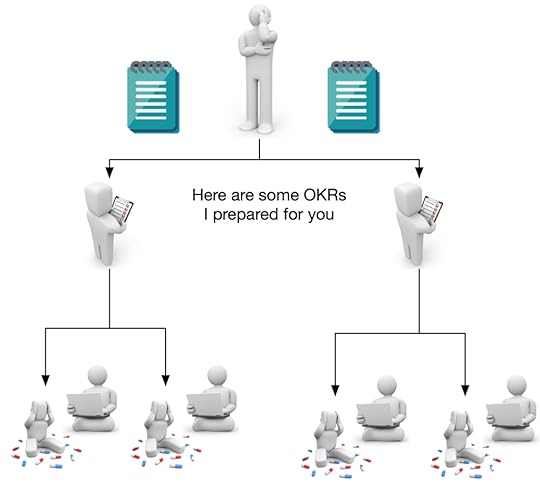

The obvious way to ensure teams are aligned with company strategy is clearly to tell them what to do. Obviously, if we have some master planner sitting at the centre they can look at the strategy, decide what needs doing and issue command, using OKRs, to teams.

Think of this like programming: there is a core controller and each team is a sub-routine which is called to do a bit. Alignment can be programmed through step-wise refinement with each layer elaborating on the ask and passing instructions down.

Obvious really. Why did even bother describing it?

Obvious and wrongObvious too is that this is not Agile. But heck, we’re all “pragmatic” and obviously achieving this kind of co-ordination requires some compromise and in this case commands must be passed around.

Personally, I have an aversion to any scheme that involves telling others what to do. There are just so many things that could go wrong, far better that to come up with a scheme that is failure tolerant.

Rather than spend my time explaining why this approach is wrong let us try a thought experiment: for the next few minutes accept I am right and we can’t tell others what to do. (Leave me a comment if you want me to set out the reasons why.)

Now the question is: what does work does?

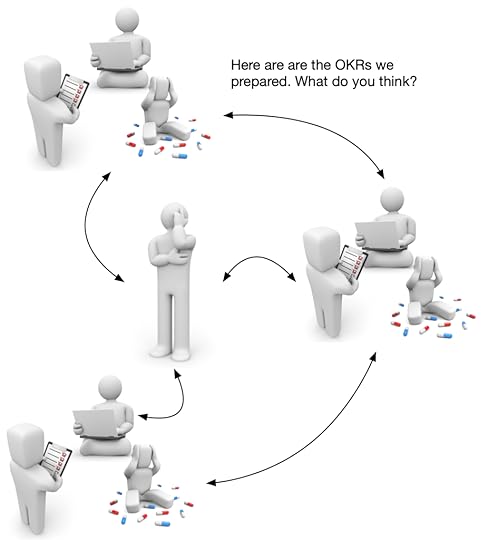

Emergent alignment.This is a design problem (“how do we are design work so disparate teams work harmoniously to a common goal?”) so the principle of emergent design should work too. We want to create a mechanism which allows design to emerge.

Now OKRs have a role to play.

By setting out what a team intend to achieve in a short, standardised, format OKRs allow intentions to be communicated and shared. Thus OKRs can be placed next to other OKRs and compared. Sharing in a standardised format allows misalignment to become clear. Once the problem can be seen action can be take to realign: OKRs build a feedback loop.

OKRs are another example an agile tool which allows problems to be seen more clearly. Someone once said “Agile is a problem detector”, for me OKRs are a strategy debugger. Simply using OKRs does not automatically solve the problem, but it makes the problem to be solved clearer.

The organisation sets out its goal(s) and strategy. Teams are asked to produce OKRs to advance on that goal. If the strategy incorporates all necessary information, is communicated clearly and teams are completely focused on the strategy then everything will work.

But, if strategy is absent, if the strategy has overlooked some key piece of information, if the strategy is miscommunicated (or not communicated at all) or teams have other demands then things will not align. When this happens there is work to do, now we want to correct problems and create OKR-Strategy alignment.

Step 1: the centre, the senior leaders set out the strategy and goals – which should themselves align with the purpose and history of the organization.

Step 2: teams look at these goals, look at the other demands on them and the resources they have, and ask themselves: what outcomes do we need to bring about to move towards those goals while following the strategy?

They write OKRs for the next period based on their understanding.

Step 3: members of the centre look at those OKRs and talk to the team. Everyone seeks to understand how the OKRs will advance the overall goal. If everything aligns then great, start work!

If alignment is missing then work is required: perhaps work on the OKRs, or perhaps the strategy needs clarifying or the goals adjusting.

Because this approach is feedback based it is self-correcting. The catch is, for the feedback loop to work people need to invest time in reading OKRs and looking for alignment, and misalignment, and correcting.

In the “obvious solution” you don’t need these time consuming steps because the centre assumes it is right and anything which goes wrong is someone else’s fault.

By the way, a smaller version of the alignment problem is sometimes called “co-ordination.” This is where two, or more teams, need to align/co-ordinate their work to create an outcome, e.g. Team A needs Team B to do something for them. The same principles apply as before, only here it is the team members which need to compare the OKRs.

So there you have it. OKRs are a strategy debugger and they create alignment by building a feedback loop to promote emergent alignment.

The post OKRs create strategy alignment but not in the way you think they do first appeared on Allan Kelly.

OKRs create strategy alignment but not in the way you think they do

One of the claims made of OKRs is they solve the problem of alignment, strategic alignment specifically. So, anyone reading my last post – Pull don’t push OKRs – might be wondering how this can be. I’m sure many people will ask how alignment can be achieved without some master plan and planner?

I’m continuing my experiment wirth Medium – let me know what you think. One of the problems I’ve been having with this blog recently is the volume of spam/scam comments that it is attracting. Switching to Medium isn’t a complete solution and I might have to switch comments off soon. Sorry about that.

The post OKRs create strategy alignment but not in the way you think they do first appeared on Allan Kelly.

The post OKRs create strategy alignment but not in the way you think they do appeared first on Allan Kelly.

June 26, 2023

Pull, don’t push: Why you should let your teams set their own OKRs

There is a divide in the way Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) are practiced. A big divide, a divide between the way some of the original authors describe OKRs and the way successful agile teams implement them. If you haven’t spotted it yet it might explain some of your problems, if you have spotted it you might be feeling guilty.

The first school of thought believes OKRs should be set by a central figure. Be it the CEO, division leadership or central planning department, the OKRs are set and then cascaded, waterfall style, out to departments and teams.

Some go as far as to say “the key results of one level are the objectives of the lower levels.” So a team receiving an OKR from on high take peels of the key results, promotes each to Objective status. Next they add some new key results to each objective and hand the newly formed OKR to a subordinate team. The game of pass the parcel stops when OKRs reach the lowest tier and there is no-one to subordinate.

The second school of thought, the one this author aligns with, notes that cascading OKRs in this fashion goes again agile principle: “The best architectures, requirements, and designs

emerge from self-organizing teams.” In fact, this approach might also reduce motivation and entrench the “business v. engineer” divide.

Even more worryingly, cascading OKRs down could reduces business agility, and eschew the ability to use feedback as a source of competitive advantage and feedback.

Cascading OKRs Cascading OKRs are handed down from above

Cascading OKRs are handed down from aboveWe can imagine an organization as a network with nodes and connecting edges. In the cascading model information is passed from the edge nodes to the centre. The centre may also be privy to privileged information not known to the edge teams. Once the information has been collected the centre can issue communicate OKRs back out to the nodes.

One of the arguments given for this approach is that central planning allows co-ordination and alignment because the centre is privy to the maximum amount of information.

A company using this model is making a number of implicit assumptions and polices:

Staff at the centre have both the skills to collect and assimilate information.That information is received, decisions made and plans issued back in a timely fashion. Cost of delay is negligible.However, in a more volatile environment each of these assumptions falls. Rapidly changing information may only be known to the node simply because the time it takes to codify the information — write it down or give a presentation — may mean the information is out of date before it is communicated. In fact the nodes may not even know they know something that should be communicated. Much knowledge is tacit knowledge and is difficult to capture, codify and communicate. Consequently it is excluded from formal decision making processes.

The loss of local knowledge represents a loss of business agility as it restricts team’s ability to act on changing circumstances. Inevitably there will be delays both gathering information and issuing out OKRs. As an organization scales these delays will only grow as more information must be gathered, interpreted and decisions transmitted out. Connecting the dots becomes more difficult when there are more dots, and exponentially more connection, to connect.

This approach devalues local knowledge, including capacity and ambition. Teams which have no say in their own OKRs lack the ability to say “Too much”, they goals are set based upon what other people think — or want to think — they are capable of.

Similarly, the idea of ambition, present in much OKR thinking, moves from being “I want to strive for something difficult” to “I want you to try doing this difficult thing.” Let me suggest, people are more motivated by difficult goals that they have set themselves more than difficult goals which are given to them.

Finally, the teams receiving the centrally planned OKRs are likely to experience some degree of disempowerment. Rather than being included and trusted in the decision making process team members are reduced to mere executers. Teams members may experience goal displacement and satisficing. Hence, this is unlikely to lead either to high performing teams or consciences, responsible employees.

Any failure in this mode can be attributed to the planners who failed to anticipate the response of employees, customers or competitors. Of course this means that the planners need more information, but then, any self-respecting planner will have factored their own lack of information into the plan.

Distributed OKRs Distributed OKR setting

Distributed OKR settingIn the alternative model, distributed OKRs, teams to set their own OKRs and feed these into any central node and to leaders. This allows teams to factor in local knowledge, explicit and tacit, set OKRs in a timely fashion and determine their own capacity and ambitions.

One example of using local knowledge is how teams managing their own work load, for example balancing business as usual (or DevOps) work with new product development. As technology has become more common fewer teams are able to focus purely on new product development and leave others to maintain existing systems.

Now those who advocate cascading OKRs will say: “How can teams be co-ordinated and aligned if they do not have a common planning node?” But having a common planner is not the only way of achieving alignment.

In this model teams have a duty to co-ordinate with both teams they supply and teams which supply them. For example, a team building a digital dashboard would need to work with teams responsible for incoming data feeds and those administering the display systems. Consequently, teams do no need to information from every node in the organization — as a central planning group would — but rather only those nodes which they expect to interact with.

This responsibility extends further, beyond peer teams. Teams need to ensure that their OKRs align with other stakeholders in the organization, specifically senior managers. In the same way that teams will show draft OKRs to peer teams they should show managers what they plan to work on, and they should be open to feedback. That does not mean a manager can dictate an OKR to a team but it does mean they can ask, “You prioritising the French market in this OKRs, our company strategy is to prioritising Australia. Is there a reason?”

A common planner is but one means of co-ordination, there are other mechanisms. Allowing teams the freedom to set OKRs means trusting them to gather and interpret all relevant information. When teams create OKRs which do not align it is an opportunity not a failure.

When two teams have OKRs which contradict, or when team OKRs do not align with executive expectations there is a conversation to be had. Did one side know something the other did not? Was a communication misinterpreted? Maybe communication failed?

Viewed like this OKRs are a strategy debugger. Alignment is not mandated but rather emerged over time. In effect alignment is achieved through continual improvement.

These factors — local knowledge and decision making, direct interaction with a limited number of other nodes and continual improvement — are the basis for local agility.

Pull don’t pushThose of you versed in the benefits of pull systems over push systems might like toes this argument in pull-push terms. In the top down approach each manager, node, pushes OKRs to the nodes below them. As with push manufacturing the receivers have little say in what comes their way, they do their bit and push to the next in lucky recipient in the chain.

In the distributed models teams pull their OKRs from their stakeholders. Teams ask stakeholders what they want from the team and they agree only enough OKRs to do in the coming cycle.

This may well mean that some stakeholders don’t get what they wanted. Teams only have so much capacity and the more OKRs they accept the fewer they will achieve. Saying No is a strategic necessity, it is also an opportunity to explore different options.

The post Pull, don’t push: Why you should let your teams set their own OKRs first appeared on Allan Kelly.

Allan Kelly's Blog

- Allan Kelly's profile

- 16 followers