Laurie Dennis's Blog, page 2

November 18, 2020

Why write Ming fiction?

“What’s a nice Jewish girl like you doing writing about the Ming founding?”

[image error]1944 book on Zhu Yuanzhang, “From Monk’s Bowl to Imperial Power.”

A California-based literary agent once asked me this after I proposed a novel about the story of the fourteenth-century Ming Dynasty founder, Zhu Yuanzhang.

How to reply?

I mentioned that I’m not actually Jewish, but I knew that was not the point of the question. The agent was trying to tell me that he thought it strange to hear the idea for such a book coming from someone who is not Chinese.

Maybe it is strange. And, needless to say, that agent didn’t bite.

But what I found stranger, as I was researching the Ming, is the fact that this incredible story is missing from the category of historical fiction written in English. Genghis Khan yes. Empress Dowager Cixi yes. Liu Bei and Cao Cao yes and yes. Empress Wu yes. Zhu Yuanzhang no.

Now, China has had a lot of dynasties, and each one of them had a founder with a strong personality. But even among the lists of all Chinese rulers, to say nothing of founders, Zhu Yuanzhang stands out. He rose from impoverished goat herder to the Dragon Throne. He survived the pox and the plague. He welcomed military innovations and launched what one modern scholar has heralded as “the world’s first gunpowder empire.” He defeated the Mongols and all other contenders during an era of warlords. He reigned from 1368-98, sired 26 sons, and his dynasty lasted for 276 years.

Americans know about Ming vases and Ming furniture. Why haven’t they heard of the Ming founder?

[image error]One of many multi-part TV shows about the Ming founder.

It’s not like Chinese writers and historians and filmmakers have not done their part for this guy. I know of 35 television series that focus on Zhu Yuanzhang. I have a bookshelf of stories, sayings, comic books and scholarship about him. He wrote his own autobiographical essay. A work of historical fiction set in the Ming founding is listed among the (minor) classics of Chinese literature.

The problem is that all the items I just cited are 用中文寫的. Zhu Yuanzhang, powerful emperor and barrier breaker, has not found a way over the language hurdle.

Maybe it’s all the Z’s in his name. Maybe it’s a curse that scholars placed on his head for destroying so many of their ranks once he became emperor. Whatever the reason, I decided to offer my own version of the stranger-than-fiction Ming founding story. I could never write it in Chinese, which is not my native tongue. However, after decades of studying the rich language (a shout-out to all my inspiring teachers, starting with Wang Laoshi way back in high school) that is Chinese, in its modern and classical forms, I have finally gotten to the point of being able to read and admire – and even gain insights and perspectives from – some of the amazing tales and epic histories that are only available in Chinese. The Ming founding is one example.

[image error]

The Lacquered Talisman, the first in my planned series, is based primarily on Zhu Yuanzhang’s 96-line rhymed life story, written in 1378, and annotated in 1988 by a scholar from his hometown, Wang Jianying. I also relied heavily on the scholarship of Romeyn Taylor and Hok-lam Chan in the U.S., along with selections from the vast supply of Ming primary sources, and the interpretation of Zhu’s life presented recently by Anhui local historian Xia Yurun. Another key source for me was the biography penned over decades of the tumultuous 20th century by Chinese historian/politician Wu Han.

The rhymed life story, titled the Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming 大明皇陵之碑, is a fascinating piece of literature that I think should be required reading for all students of world history. Zhu Yuanzhang was busy when he founded his dynasty in 1368, so he asked a respected scholar to ghost write his autobiography, which the new emperor wanted carved into stone and mounted in front of his parents’ graves for all eternity to read. But when the emperor went to see the finished product, he was not impressed. As he put it, “I realized the original text for the Imperial Tomb Tablet had been embellished by the Confucians ministers to the point that I feared it would not sufficiently admonish later generations and descendants.”

Take it down, the emperor ordered. He picked up his own brush and wrote out the version that still stands today in northern Anhui Province.

[image error]The Imperial Tomb Tablet stands outside the town of Fengyang, in northern Anhui Province.

I have gazed in awe at this enormous, cracked piece of rock, with its worn columns of characters. Poring over the text, I realized that Zhu Yuanzhang did not call himself a rebel or use the phrase “Ming Dynasty.” He didn’t get around to the glories of his rise until line 60. Instead, his focus was on his family’s suffering. He wanted the world to understand the sacrifices his parents made and the hardship of having his family torn apart by poverty and pestilence. He wanted his descendants, who he knew would live in palaces, to remember that he and his fellow villagers were reduced to eating bark to survive the drought years. He wanted to make clear that when his family had no place to bury their dead in the midst of an epidemic, an evil landlord turned him away, but then that landlord’s brother took pity “and kindly offered some yellow earth.” Where’s the grave of that evil landlord today? His name is only known to history because Zhu Yuanzhang exposed it.

The first 53 lines of the Imperial Tomb Tablet provide the framework for my novel, The Lacquered Talisman. I have translated all 96 into English, with annotations for each line, and made this translation available as a free PDF download. Mine is the only complete English translation available, which I find strange.

[image error]The final 1965 version of Wu Han’s masterpiece.

Wu Han’s Biography of Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋传, is another fascinating source. Like Zhu Yuanzhang in the early 1300s, Wu Han lived in tumultuous times. He finished the first version of his biography in 1944, writing without access to his own library in Beijing, since he was living with scholar refugees who had fled the Japanese occupation and landed far to the south in Kunming. Wu intended from the beginning to write a popular book, and when he was able to get back to Beijing, he added notes and citations and made various changes, but held on throughout to the vivid, page-turning feel of this life story. Here’s how he described his subject in the opening chapter on the founder’s youth: “Yuanzhang had grown into a boy of large stature, with a dark visage, and a jaw that jutted out well beyond his upper lip. He had high cheekbones, and his nose and ears were quite large. When taking in his entire face, it resembled a three-dimensional version of the character for ‘mountain (山)’ set sideways, with a bony lump in his forehead like a hillock. His eyebrows were thick and his eyes protruded. His appearance, while unappealing, nonetheless had a strange kind of balance; it was quite awe-inspiring and composed.”

Wu Han consulted with such experts in uprisings as Chairman Mao Zedong as he perfected his manuscript. The published book remains an authoritative text and indeed has been hailed as among the best biographies written by a modern Chinese author. It required a few years for me to digest, dictionaries in hand, because — alas — no translation is available in English.

[image error]Wu Han 吴晗

Wu Han published his book in 1965, as the Cultural Revolution was breaking out. Some thought his book on Zhu was actually about Mao. The infamous “Gang of Four” charged him with denying “the great function of the peasant uprising.” This in a story about a goat-herder who rose through the ranks of the Red Turbans to storm the throne. Truth then, as now, could be twisted to serve the purposes of those in power. Wu Han died in prison in 1969, one of the first victims of the Cultural Revolution.

Why would he publish a biography of one of China’s most powerful emperors at such a politically sensitive moment? Scholars have asked this question, and I personally would assume he could not stop himself. As historian Mary Mazur has pointed out, Wu Han was fascinated with how the past shaped the present, and both he and Mao Zedong “understood that Zhu Yuanzhang was key figure in China’s past who had great relevance to the present goal of formation of the new revolutionary Chinese state.”

It is no small irony that Wu Han’s life work — which described an emperor known for his own purges and which destroyed its author in a purge — survived the Red Guards. Today, Wu Han’s biography is widely available across China in reprint after reprint. The story of Zhu Yuanzhang is popular there, in no small part, because Wu Han told it so well.

[image error]

So why did a person like me decide to write a novel about a topic like the Ming founding? Because I learned from Wu Han the power of storytelling for talking about Zhu Yuanzhang, and I learned from the founder himself that it’s not in the glories but the despair that his story can best be understood. That’s a task well suited for fiction.

It’s been my strange fate to become engrossed in this life story. The more I learn about Zhu Yuanzhang, the more relevant his life seems to my modern world. I wish his name was easier to pronounce in English. I hope my work is worthy of his legacy. Meanwhile, I’m two-thirds through Book Two.

October 19, 2020

Great Ming B-day Giveaway!

October 21 on our modern calendar corresponds in 2020 with the 692nd birthday of Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, the subject of my book on the founding of China’s Ming Dynasty, The Lacquered Talisman.

I am celebrating with a series of Ming Founding Fun Facts and a Birthday Book Giveaway through my Instagram account, @lauriedennis1368.

Hope you can join the fun!

August 23, 2020

My son, my book cover artist

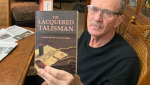

[image error]Structuring a novel is a murky process, but one moment stands out in my mind as key to both my novel, The Lacquered Talisman, and its cover, which was created by my son.

I was sitting on the floor of a bookstore in Boston, flipping through art books about China, when suddenly it hit me: What I needed for my main character was a talisman. And this talisman would be a seal chop. The Lacquered Talisman is about the Zhu family, whose youngest son founded the Ming Dynasty in 1368. I needed a tangible item that could symbolize family for my protagonist. Thus the talisman.

Th[image error]is literary device in my novel became a stylized version of an actual item that sits on my writing desk. It’s a polished black plastic box that a friend gave me years ago, when I was living in Jiangxi Province and working as an English teacher. The finger-sized box has a sliding lid that opens to reveal two compartments, one holding red ink, and the other a small chop, carved at one end with my Chinese name. For The Lacquered Talisman, the chop would be modified in various ways that became my job as a writer to convey so that the reader could understand and relate to the item. As I was writing, I often picked up my chop box and held it in my hand, gazing at this small oval object as I imagined its mystical counterpart hanging on a leather string around my protagonist’s neck and making its way through my novel.

When it came time to think about book covers, I knew that I needed to feature the talisman. But how to do this? I can’t draw, and as a first-time author, I wondered how much control I would have over my cover, that critical image and first connection of a reader with my story. How would I explain my chop box to an illustrator?

Luckily, my son is an artist. And luckily my publisher was willing to humor a mom who wanted her son to design her book cover.[image error]

My son, Kerry, is a student in the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Peck School of the Arts. And to my everlasting good luck, he was taking a class in digital arts the very semester when I was needing a book cover. It became his midterm.

I’m not sure how a writer is supposed to interact with a book cover designer, but as a mom talking to her son, I was able to be very specific. Maybe even bossy. And I could pester the artist as much as I wanted.

Kerry got to learn about Chinese talismanic writing, and try it out for himself. This is an esoteric and magical form of writing used on Daoist charms and intended as a way to summon the gods.

“Make it wavier.”

“Now it looks too much like an insect.”

“Make it red.”

“No, make it black.”

[image error]

Kerry worked patiently through all my requests, and then started to ignore them, turning the cover into his own piece of art, which is what artists do. So I stepped back and let the cover proceed until we had something that we could both admire. Like the talisman itself, the book cover evolved into a motif for our family’s investment in this story, which has taken me years to write, a story about families that has been immersed in my own family and benefited from that synthesis.

The book cover was eventually turned in – to both Kerry’s teacher and my publisher. And now my published novel sits on my desk, right next to my little black chop box. I consider these my good luck charms for Book 2, cover yet to be determined.

August 16, 2020

Five-star review of THE LACQUERED TALISMAN

Here’s a five-star review of my debut novel published August 12, 2020 on IndieReader.com, a website devoted to self, hybrid and small press published authors:

THE LACQUERED TALISMAN leads readers from the marriage of the first Ming Emperor’s parents, through his young life, and his years of devotion as a Buddhist monk, to the beginnings of the rebellion that would overturn a dynasty and set him on the throne of one of the greatest empires the world has ever known.

Source: THE LACQUERED TALISMAN

July 2, 2020

Re-opening for business…a ‘Call to Commerce’ Tower in 1100s China

The city leader was concerned that all the businesses in his town were shuttered. People were afraid to go out. He asked the central government for tax relief, and then embarked on a major project to get people shopping again.

Sound familiar? The concerns are the same type that officials today are dealing with in the face of COVID-19, but the city leader I am referring to is Xin Qiji 辛弃疾, one the Song Dynasty’s military prefects in Chuzhou 滁州, a city across the Yangtze River from Nanjing in China’s heartland. And the danger Xin Qiqi faced in the 12th Century was not a pandemic, it was the Jin cavalry poised for yet another invasion from the north. Xin Qiji’s signature solution was also not something mayors or governors in the U.S. are currently considering: he built a soaring pavilion, the tallest structure in Chuzhou, located in today’s Anhui Province.

“Literary types love towers, this has been true since ancient times,” wrote Qian Niansun 钱念孙 in a recent travel book about Anhui. “Most climb or build them either to visit scenic spots or wax poetic, but Xin Qiji established Pillow Pavilion 奠枕楼 in Chuzhou for quite another reason…Pillow Pavilion was actually an 800-year-old ‘Call to Commerce Tower.’”

The pavilion was designed with flashy style and set in a prominent place above a shopping district.

[image error]Chuzhou, in today’s Anhui Province, is across the Yangtze from Nanjing.

It was part of Xin Qiji’s three-part strategy in 1171-72 to stabilize Chuzhou, which he considered the last stronghold before the river, the teeth to Nanjing’s mouth – because if Nanjing were to fall, then the capital of Hangzhou would be next.

If everyone was fleeing Chuzhou, and the businesses and hotels were all closed, so that the traveling merchants were not feeling safe keeping Chuzhou on their routes, then Xin Qiji knew he could not rebuild the city. So Xin Qiji asked the court for funding to help with tax relief, defense, and a big fancy tower. Xin Qiji was a military statesman, but he was also considered a first-rate lyricist, so of course he wrote a poem about his Call to Commerce Tower, which begins like this:

Travel weary and dusty, guests meet on the road

and exclaim over the tower emerging like an illusion.

They point to the soaring eaves

that ride the clouds like waves.

I came across this story while researching my second novel in a historical fiction series about the founding of China’s Ming Dynasty in 1368.

In the 1350s, the first city that the future Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang 朱元璋 claimed as a base was Chuzhou, which he captured for the Red Turbans in the summer of 1354. For Zhu Yuanzhang, Chuzhou was a place where he could establish himself as a new kind of leader in the rebellions sweeping across the Yangtze River Valley. It was the city where his name first started to resonate, which meant that the nieces and nephews and in-laws Zhu thought he had lost forever started to turn up at the Chuzhou gate, seeking his protection. This resulted in one of my favorite passages in the autobiographical essay Zhu later wrote, “To be able to gather together was like being born again. We grabbed at each other’s clothes and remembered old times for as long as we could.”

Today’s Chuzhou is a provincial city on the outskirts of the thriving Yangtze River Delta region, but for much of its history, Chuzhou was a border town, and so flared in importance whenever battles raged. It’s known as “the tail of Chu and the head of Wu 楚尾无头,” because it sits on the edge of both of those ancient kingdoms. The Jurchens, the Mongols, the Manchus – their armies all came down from the north to rip through Chuzhou in successive invasions of China. Xin Qiji’s poem continues:

This year peace extends across the land,

Enemy troops have been pushed back from the river,

Though their cavalry may threaten again come autumn.

I lean from the tower railing, and notice the fine breeze from the southeast,

Moving northwest across the Divine Land.

[image error]Today’s Pillow Pavilion 奠枕楼 in Chuzhou.

That was the history that drew me into the city, but I was surprised at the tower story. The original Pillow Pavilion is long gone and people aren’t even sure where exactly it stood, but in 2017 the city of Chuzhou “rebuilt” it, no doubt in a location that would serve as a current call to commerce.

It is a kind of bittersweet consolation to know that people in distant eras suffered through the kinds of problems we consider modern and novel. Will the businesses ever reopen? Will the current catastrophe ever come to an end? Maybe recreating an 800-year-old Call to Commerce Tower is a sign that we will prevail; or maybe that we will never learn from our mistakes.

Here is how Xin Qiji ended his poem on Pillow Pavilion:

For now I focus on the happy mood,

Turning my attention to a game of matching verse, enhanced by wine.

My dream for aiding my country,

Is that in all years the people here can, as in the past, roam free.

Here’s the text for the entire poem:

征埃成陣,行客相逢,都道幻出層樓。指點檐牙高處,浪涌雲浮。今年太平萬里,罷長淮、千騎臨秋。憑欄望:有東南佳氣,西北神州。

千古懷嵩人去,還笑我、身在楚尾吳頭。看取弓刀陌上,車馬如流。從今賞心悅事,剩安排、酒令詩籌。華胥夢,願年年、人似舊遊。

辛棄疾,《聲聲慢(滁州旅次登奠枕樓作,和李清宇韻)》

May 25, 2020

Hok-lam Chan, frenzied fictions, and the meaning of Zhu Yuanzhang’s name

Photo: The author with Professor Chan at a 2006 conference in Hong Kong

Since today is Memorial Day, a time to keep alive the memory of heroes in our lives, I would like to write about a historian who took me under his wing: Hok-lam Chan 陳學霖, 1938–2011.

Professor Chan was a prolific scholar who fought against viewing fiction as fact. He also spoke the bold truth about the transition from the Mongol Yuan to the Chinese Ming Dynasty in the 1300s, a period shrouded in mythmaking and politics and the rewriting of slander as truths – in short a period not unlike our own.

To my great fortune, I stumbled upon one of Professor Chan’s articles at the beginning of the research that led to my first novel, The Lacquered Talisman, which is about the Ming founder. Since I was writing historical fiction, I needed to be clear about fictions and facts before trying to blend them into a novel. I needed a scholar devoted to factual knowledge and to that which is concrete and observable in the Ming founding.

At that point in my book project, I was susceptible to some of the fabulous stories told about the Ming founder, Zhu Yuanzhang, who led an undeniably remarkable life. His story encompassed such extremes – the patient military genius who became a merciless emperor, the impoverished peasant who rose to the dragon throne, the devoted husband of Empress Ma who fathered countless children by many courtesans – that it becomes seductive to accept obvious fantasies as historical record. It takes someone like Professor Chan to throw cold water on that tendency.

“The more dramatic the dynastic founding, the greater the degree and intensity has been the mythologization,” Professor Chan wrote.

I had no problem setting aside stories about brilliant red lights and fragrant perfume issuing from the house where the founder was born (which Professor Chan called “bizarre episodes”). However I was chagrined to learn that when the Ming founder wrote so convincingly about praying to the gods over whether to join the Red Turban rebellion and receiving a thrillingly decisive answer, he was in fact repeating an anecdote told about a previous dynastic founder. As Prof. Chan explained, Zhu’s fateful prayer story “transformed a well publicized anecdote about the rise of the rebel leader into a mystical manifestation indicating the decent of a son of Heaven in official historiography.” Yes, but this manifestation was a fiction I preferred as a fact! However, falling for such mythmaking made me no better than those who saw five-colored clouds and other omens wherever their preferred prince appeared, an act Prof. Chan dismissed as falling for “frenzied fictions.”

Prof. Chan was equally dismissive of the Ming founder’s haters. Yes, the Ming founder became paranoid and ruthless, but no he was not illiterate. Prof. Chan had no patience for scholars who tried to portray Zhu Yuanzhang as a despot who persecuted and killed Confucians because he couldn’t read their writing.

“The fact is that (the Ming founder), despite his humble origins and lack of formal schooling in his early years, had acquired a rudimentary classical education through self-education and tutelage from the Confucian scholars during his rise to power… (His writings), though not very elegant and ornate by classical standards, are highly intelligent and readable; the style is direct and forceful, and the language, despite frequent occurrences of colloquialism, is plain and expressive.”

Prof. Chan was born in Hong Kong, received his PhD in history from Princeton, and taught at Columbia University, the University of Washington, and at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. It was at the beautifully tropical and hilly campus of the latter that I first met him, at a 2006 conference, “Ming Taizu and His Times.” (“Taizu” is the posthumous temple name for the Ming founder.)

I was an unaffiliated writer at that point, but I had been peppering my old friend, the historian Edward L. Farmer of the University of Minnesota, with questions about Zhu Yuanzhang. Prof. Farmer was a co-organizer of the Hong Kong conference, and invited me to present a paper on my research into the women in the Ming founder’s world. I was assigned to a two-person panel titled “Imperial Family Relations,” that consisted of me and…Hok-lam Chan.

I had no idea how to greet the professor who was the leading authority on the field I was immersed in, so I think I just slid meekly into my seat and waited for my turn to present my findings. I wasn’t sure if it was even appropriate for me, a writer of fiction, to be sitting next to him, an advocate for facts. My unease was alleviated by Professor Chan’s interest in my paper. He was the kind of scholar who possessed a vast amount of knowledge, and could assemble it and filter through it to make his points, but did not use his expertise to dominate. His focus was on keeping scholarship attuned to the best available evidence. He listened to my points, considered them, and then offered helpful insights. He confirmed my suspicion that it was slander to suggest that Empress Ma had no sons. After the conference, in response to my suggestions about the parentage of the son that mattered – the one who followed Taizu to the throne as the Yongle Emperor – Prof. Chan sent me one of his articles on the subject, which explained in detail why Empress Ma was likely not that son’s mother.

Thus began our correspondence, culminating in our joint publication of an essay in historian Sarah Schneewind’s edited volume, Long Live the Emperor! Our essay is titled, “Frenzied Fictions.”

Professor Chan died nine years ago – on June 1, 2011 – a few days before surgery scheduled to fix his chronic heart condition. I wish more than anything that I could give him a copy of my novel, which came out this spring and benefited so much from his scholarship.

I am currently working on Book 2 (it won’t take as long as the first!), which includes a scene about the moment when Zhu Yuanzhang receives his formal name. For that scene, I pulled out one of my notes from Professor Chan. I had asked him if the character Yuan 元 was a reference to the Mongol “Yuan” dynasty, so that the word Zhang 璋, which means “jade scepter” could make the full name mean something like “the jade scepter that will destroy the Yuan”???

“Wishful thinking!” Professor Chan replied.

Should the “Zhang” character be read to have a meaning of “brightness” in a way that was tied to the “Ming” of the Ming Dynasty, which also has this meaning?

“No!”

He was clear that I should not associate Zhu Yuanzhang’s name with either the Yuan or the Ming dynasty names.

“It probably means the ‘original bright jade,’” Professor Chan wrote. “It’s quite a proper name, from the Confucian classical point of view.”

He followed this with another one of his articles, about symbolism in the Ming dynasty, an article which he inscribed to me and to which I refer frequently.

As someone who spends as much time as possible immersed in historical records, I have tremendous admiration for a scholar like Hok-lam Chan, who devoted his life to understanding a complex and important transition era: the fall of the Mongol conquest dynasty and the concomitant rise of the Ming. I admire him not only for his expertise, not only for his strong writing, but also for his willingness to take seriously a person like me, a writer of fiction. I feel so lucky to have been able to talk over the Ming founding with Hok-lam Chan. I wish I could talk with him still, especially because I know his eyebrows would rise with disapproval over some of my fictional anecdotes. I wish I could explain to him some of the choices I made. I wish I could get his review, which I know would be honest and unreserved.

Instead I can only pull out his notes and bring them with me into my stories, hoping he would not cross out my fictions as too frenzied.

[image error]My correspondence with Professor Chan.

[image error]The 2006 conference at which I met Prof. Chan. I am in bright blue in the middle. He is in the row in front of me, in a dark suit and dark tie, looking over the shoulder of Professor Edward Farmer, who is wearing a corsage as a conference organizer.

May 2, 2020

The impact of the Black Death on 1300s China: No plague = no Ming

If not for the plague, China wouldn’t have a Ming Dynasty.

This startling thought has been on my mind as I sit at home in quarantine, enduring the epidemic of my era: COVID19.

Of course, if the Ming had not been founded in 1368, some other dynasty would have followed Kublai Khan’s Mongol Yuan. Perhaps the salt smuggler Zhang Shicheng would have prevailed with his Great Zhou Dynasty based in the city of Hangzhou (which the Ming founder squashed in 1367). My point is that the plague is what propelled the Ming founder onto the path that led to the founding. It is the single incident that pushed him off his expected trajectory of farming alongside his brothers in the fields along the Huai River. Zhu Yuanzhang was the youngest of four sons. If not for the plague, he would never have left his large family, which needed him in the fields. He death would have been unremarkable and we would know nothing about him.

But the plague did strike. It wiped out Zhu Yuanzhang’s family. It left him alone surrounded by nothing but corpses.

As he put it: “俄爾天災流行,眷屬罹殃. All at once, calamities gripped the land and my family met with disaster.” In a matter of days, his father, then his elder brother, then his nephew, then his mother all died. His elder brother’s wife snatched up her two young children and left. His second brother went mad with grief and wandered away, never to be seen again.

It was the worst moment in Zhu Yuanzhang’s long life.

This was in 1344, when Zhu was 16 years old. It took another 24 years for the Ming to get founded, any many things happened in between – Zhu became a Buddhist monk, then joined the Red Turban rebellion, then became one of its leaders. And in the end he defeated all contenders. But the event that launched Zhu Yuanzhang toward fame and glory was the decimation of a plague strike. He would not have been dispatched to the local Buddhist temple if he had not lost his entire family. Maybe the Red Turban movement would have tempted him and his brothers, but the cost of leaving his family would have been a barrier. He wrote about this after becoming emperor:

“I personally saw rich people, middle people, and destitute people happily joining the rebellion…they cast away their fields, gardens and houses…Many families were totally annihilated. This is the bitter disaster faced by those who love rebellion.” (excerpts from translation by the late John W. Dardess, Confucianism and Autocracy, page 189)

Zhu Yuanzhang despised those who deserted their families to join the rebellions, maybe all the more so because he landed in the midst of a rebellion after having lost his own family. To the plague.

Knowing this history has caused me no small amount of exasperation when I read accounts of the Black Death that act like this pandemic had no impact on China and is only relevant to Europe.

A 2011 article titled “Was the Black Death in India and China?” cites “the absence of any firsthand description of plague or its symptoms in Mongol sources or in the writings of merchants and travelers on the Silk Road anywhere to the east of the Caucasus and the northern shore of the Black Sea in the years leading up to the Crimean outbreak of 1346.”

This is typical.

My April 20 issue of the New Yorker has a nice feature on Anthony Fauci that says, “And, in the fourteenth century, the Black Death swept through Europe, killing more than half the population.” And what else did this pandemic do?

I remember once standing in the Boston Public Library going through a whole shelf of plague books and suddenly realizing they all assumed the Black Death only had an impact on Europe. I started to get mad and may have treated a book or two rather roughly and even snorted aloud as I started paging through indexes and not finding “China.” Or even “Asia.”

And yet, A 19th-century Russian scholar (D.A. Chwolson) deciphered tombstones written in Syriac from a Nestorian Christian community along Lake Issyk Kol, located in today’s Kyrgystan, a few miles from China’s border. The grave stones say things like, “This is the grave of Kutlik. He died of plague with his wife Mangu-Kelka,” and give the year as 1339. The graveyard reveals a high death rate that year. It was located on Mongol trade routes linking Central Asia with China.

Xia Yurun, a historian based in Fengyang, Anhui Province, the birthplace of the Ming founder, has studied the local accounts of the epidemic that struck that region in 1344, and notes that some think the disease that wiped out the Ming founder’s family may have been cholera, or some unknown disease. But Mr. Xia concludes, “clearly the origin of this ‘heavenly disaster’ is the earthshaking historical event known as the Black Death.” (Zhu Yuanzhang and Fengyang, page 91.)

I agree. And to those who think the Black Death had no impact on China, I would suggest that this epidemic shook loose a young peasant in a rural area of northern Anhui Province. It hardened and tempered this young farmer, imbued him with a fear and awe of the great impermanence of our existence, and propelled him onto the world stage.

“予亦何有,心驚若狂. As for myself, what did I have but fear to the point of madness?” said Zhu Yuanzhang, in his description of the aftermath of the plague.

But he prevailed. He became known as “a hero, a bandit and a sage – all at once.” His dynasty ruled China for 268 years.

No plague, no Ming. You never know what kind of change a pandemic will bring.

April 16, 2020

The never ending story of translating Chinese texts

It took the founder of China’s Ming Dynasty ten years to get his life story published – as a text carved into a stone tablet still standing in northern Anhui Province.

It took another 639 years to get that story translated into English – as a PDF on my blog.

The original text was finalized back in 1378 when the carving was complete and the tablet was placed on the back of a huge stone turtle. The English final draft will probably never stop getting tweaked, most recently today, when I took the suggestion of a student at UC, San Diego and revised the concluding line. That’s the nature of translation: an imperfect but necessary process that can always be improved.

When I first became aware of the Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming 大明皇陵之碑 (the title of Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang’s autobiographical essay, written to be placed before the graves of his parents), I was surprised to realize it hadn’t been fully translated.

It’s an amazing text, a concise account of a legendary life, and a unique story of a peasant who rose to become one of China’s most powerful emperors. It’s widely quoted in historical work in English, but is among the many important Chinese documents that simply hadn’t been published in a complete form in English.

Translation of old Chinese texts is time-consuming and is best done in consultation with native speakers of both Chinese and the translation language. The resulting product is not necessarily going to be of interest to publishers, which makes it a thankless effort for many scholars. (Though the Ming History English Translation Project is an important new web resource.) Also, classical Chinese is terse to a degree that makes putting it into English a daunting task. It’s usually much easier to just quote the relevant passage and move on.

However, since I was working on a novel about the Ming founder’s family background, I needed to understand this text in its entirety. And I had the notes (in Chinese) of a scholar, the late Wang Jianying, who studied the Chinese original and examined the tablet in Anhui. Thus began the translation project that resulted in a free downloadable PDF first posted to this website in 2017.

As I have mentioned elsewhere, one fascinating aspect of this text is that it does not focus on the glory of founding a Chinese dynasty. Zhu Yuanzhang spends the entire first third of his story on a single incident: the plague deaths of spring 1344. The second third depicts how the survivors reeled from those losses, and how Zhu ended up a Buddhist monk, wandering the Huai River valley until the gods instruct him that he must set aside his monastic life to become a soldier.

My novel, the Lacquered Talisman, is a fictional version of the first two thirds of Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming.

Also of interest is that the tablet standing today in Anhui is a revision. Zhu Yuanzhang did not like the first draft, which was commissioned shortly after the founding of the Ming in 1368. That version was crafted by a Confucian scholar, and Zhu decided it had been embellished “to the point that I feared it would not sufficiently admonish later generations and descendants.” So he had the original taken down and he wrote the final text himself.

My translation is based on my own understanding of Zhu Yuanzhang’s words, but I have benefited from suggestions by history students at UW-Madison and elsewhere. Most recently Qiupeng Guan, a sophomore in international business at UCSD, pointed out that my final line had Zhu offering “this text” for time everlasting, when in fact he was wanting to see “ritual offerings” for time everlasting. So I tweaked that line.

This is one benefit of translation in the age of the internet. Imagine trying to explain to Zhu Yuanzhang that a Zoom chat with a history class resulted in an improved PDF of his life story for upload to my blog.

Of course, the Ming founder would not have seen any need to put his story into English, a language irrelevant to his world. But I think he would have smiled at the thought of his text being transmitted to other languages as a kind of “ritual offering” in words to his parents. And so he would have thanked the UCSD student for the correction, and ordered that the revision be carved into my PDF tablet at once.

Translations, even ones carved into stone for time everlasting, are living texts. The words can be written down in a final form and posted for all to see, but will always be one click away from refinement.

April 11, 2020

Publishing in a pandemic…

I am starting to feel like a case study in how not to time your book release.

First, I stretched out the manuscript editing process so that my debut novel release date planned for late 2019 was postponed to February 1, 2020. It’s a nice date, except that my publisher is located in China, with a printing press in Hong Kong that closed down right about then to combat COVID-19.

Next, I held off on book promotion in the U.S., where I live, to allow time for getting the book printed. “Let’s give it six weeks,” I decided. That timed my first mid-March book promotion gig for the exact moment when things started to shut down around me in Wisconsin.

What incredibly bad timing! Or rather, what an inescapable virus. I am thankful to be able to safely quarantine with my family, but stunned at this pandemic’s reach into all aspects of all of our lives. The comparatively small matter of my personal book release plans made me more attuned to news stories of all the artists and actors and writers who had been planning to debut their creations and talents when this virus slammed doors shut around the globe.

Now that the coronavirus crisis in Hong Kong and China has thankfully started to lift – maybe? – my books have managed to get printed. Friends and family report being able to order copies on-line. They have sent me pictures, snapshots that I am collecting and savoring.

I have a pile of my darlings sitting in the middle of my living room floor and I hate to see them gathering dust. I put on a mask and went to the post office to mail a few copies, but then felt guilty about putting mail carriers through the non-essential duty of debuting my novel.

So I’ll wait.

I know I have the luxury to be able to wait, when others don’t. Nonetheles, it’s easy to get lost in the despair of this moment because so much is going wrong. When I feel frustrated about my own situation, I try to focus on continuing to write, because that is something positive. I also give thanks to my community of writers, because they are so supportive and their various projects are inspiring and motivating. And I especially give thanks for readers everywhere, because novels are meant to be read.

February 13, 2020

So my book about the plague is a victim of coronavirus…

According to my publisher, my first novel is now waiting in some printing queue in China, one small item lost in the general shutdown resulting from the coronavirus. Ironically, “The Lacquered Talisman” focuses on how the Zhu family dealt with the contagion of their era: the plague. When the day comes that I am able to hold a copy of my book in my own hands, I will feel a measure of relief that the current contagion is subsiding. Until then, my thoughts are with all those in China dealing with this crisis.

Here is how Zhu Yuanzhang wrote about the impact of contagion on his family:

俄爾天災流行,眷屬罹殃. All at once, calamities gripped the land and my family met with disaster.

皇考終於六十有四,皇妣五十有九而亡. My imperial father had reached the age of 64, and my imperial mother 59, when they perished;

孟兄先死,合家守喪. My eldest brother was keeping vigil with the family before he died.

殯無棺槨,被體惡裳. Carried to the grave with no coffins, the bodies were shrouded in rags;

既葬之後,家道惶惶. After the burial, the path before us was fraught with suffering and worries.

里人缺食,草木為糧. In my village, food was scarce, with grasses and bark serving as nourishment.

予亦何有,心驚若狂. As for myself, what did I have but fear to the point of madness?

This is an excerpt from my translation of Zhu’s autobiographical essay, known as the Imperial Tomb Tablet of the Great Ming because it was carved into stone and mounted before the graves of Zhu’s parents after he founded the Ming Dynasty. You can read my annotated translation of the entire text by clicking on the PDF in this link.