Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 51

January 8, 2020

A video teaching on "in-between" times and spiritual practice

When we were in Cuba, the rabbis on the trip asked Cuban Jewish communities what they most needed from us. They asked for regular video teachings. That led to Bayit's latest initiative: monthly video teachings, translated into Spanish, for the Jewish communities of Cuba and anyone else who's interested.

Our first Spanish-language teaching went live in December, featuring Rabbi Sunny Schnitzer of Cuba America Jewish Mission teaching about Chanukah. You can find that teaching on Builder's Blog here. Our second teaching is now live; this one features me, talking about in-between times, spiritual life, and spiritual practice. Unlike R' Sunny I'm not fluent in Spanish, so my "vort" is recorded in English. Rabbi Juan Mejia is graciously translating our work into Spanish, so my video has Spanish subtitles!

If you're interested, you can watch the video here:

Palabras del Torá / a "vort" of Torah - R' Rachel Barenblat from Bayit: Building Jewish on Vimeo.

Or, if you'd prefer to read the teaching, the text is available online in Spanish and in English -- just click through to Builders Blog.

January 7, 2020

A year ago

A year ago you kept falling. Bloodied from landing,

bruised as though beaten. Dad couldn't lift you, so one

night you slept on the carpet until morning. Did you know

your children were scheduling frantic conference calls?

There was no knowing how much worse it might get.

When you consented to hospice, you texted us, "if my decline

troubles you, have your doctor prescribe a happy pill."

I laughed until I cried. A year ago you were still alive.

This month I keep saying that, like a mantra.

Soon I'll never be able to say it again.

January 3, 2020

Vayigash: choosing again

In this week's Torah portion, Vayigash, there's a poignant moment when Joseph reveals himself to his brothers.

In this week's Torah portion, Vayigash, there's a poignant moment when Joseph reveals himself to his brothers.

Last year I was struck by the beautiful Hebrew word להתודע, "to make oneself known" or "to reveal oneself." This year what leapt out at me is the precursor to Joseph's revelation of self. Before he could make himself known to his brothers, he needed to know that they had changed. He needed proof of their genuine teshuvah, their repentance, their turning-themselves-around.

But how could he get that proof? He couldn't exactly ask. So he demanded that they abandon their youngest brother Benjamin in Egypt. Judah's response -- "I promised our father that we would keep him safe. He's already lost one beloved son; if he lost this one too, it would kill him; take me instead" -- proves to Joseph that Judah, at least, is different than he once was.

Judah has learned from the brothers' mis-steps. He understands now that their scheme to get rid of Joseph caused incredible harm to their father... and presumably also to Joseph, though he doesn't yet know that he's speaking with the brother they sold down the river. Presented with the opportunity to make a similarly damaging choice a second time, Judah chooses differently.

Heraclitus famously wrote that one can't step in the same river twice. But Rambam argues that we can. In fact, that's precisely how he says we can tell if our teshuvah -- repentance and re/turn -- is genuine. When we are presented with the same opportunity to miss the mark, and we choose differently, then we know that we've really made teshuvah. We've done the work to actually change.

Conventional wisdom holds that "[w]hen someone shows you who they are, believe them." In general I think that's a good rule of thumb. Our actions and choices show who we are, and sometimes they reveal realities we might not want to admit. We can say all kinds of pretty things about who we imagine ourselves to be, but when push comes to shove, our actions will speak deep truths about who we are.

If someone says they value kindness, but they act in ways that are unkind -- if someone says they are truthful, but they act in ways that are mendacious -- if someone says they are ethical, but they act in ways that are power-hungry or abusive -- I'm inclined to say, then believe them. Their actions show who they have chosen to be. It's reasonable to expect their choices to continue.

And yet -- Judaism stands for the proposition that change is always possible. As is written in the CBI Board covenant, which is posted in our social hall, "We acknowledge that things can always change; can always be better than they have been." Things can always change. People can always change -- if we put in the hard work that's required in doing so. But we have to choose to change.

Change isn't easy. Our actions and our choices carve grooves of habit on heart and mind, and it's difficult to become someone new. Difficult, but not impossible. Authentic spiritual life asks us time and again to do what Judah did: to face our mis-steps, to apologize and make things right, and when our lives lead us to the same river again, to choose other than we did before.

Judah's teshuvah leads to their family becoming whole again. It leads to plenty and prosperity instead of famine and sorrow. I believe that doing the work of teshuvah can open us to abundance too. Not necessarily a full pantry and a family reunited -- but surely the comfort of knowing that we're doing the work and "walking our talk." That we are living up to who we say we are.

I have the sense that the coming year will challenge us, repeatedly, to do our inner work -- and to live up to the values we say we hold dear. What are the values we want to embody this year... and what tools can we use to keep ourselves honest, so we're not just paying lip service to Jewish values but actually taking action to live them, every day?

This is the d'varling I offered at Shabbat morning services. (Cross-posted to my From the Rabbi blog.)

December 29, 2019

Light in the darkness

This is the message I sent to my congregational community this morning. I wanted to share it here also, in case it speaks to any of you.

Dear all,

I woke this morning to news of yet another antisemitic attack during Chanukah — this time a stabbing at a Chanukah celebration in Rockland County, New York. This is the eighth such incident I’ve seen in the news since Chanukah began. I expect that many of us are reading these news stories this week. And I expect that in response many of us are navigating a mixture of fear, anxiety, sorrow, and more besides.

As I was sitting with today’s news, I received a text from a member of one of the Cuban Jewish communities that we visited earlier this fall. She asked if we are all right, and said that they are concerned for our safety. In an instant, her heartfelt expression of care shifted my morning. And in assuring her that we are all right, and that though these are dark times I know that light will prevail, I reminded myself of what I know to be true.

In recent months the CBI Board has upgraded our security system so that we can be safer when we gather together in our synagogue for learning, for prayer, and for community. The best response to antisemitic attacks around the nation, and the best response to whatever arises in us because of those attacks, is precisely that — gathering together. As we move into 2020, may we continue to come together in our sorrow and in our joy.

And when we come together in 2020 for Shabbat and festivals, Hebrew school and Take & Eat, baby namings and funerals, may we bring our Christian and Muslim and Buddhist and Hindu and atheist and secular friends and neighbors along, too. Invite a friend or colleague who isn’t Jewish to services, or to seder, or to a Shabbat meal in your home. Because the better we know each other, the more we can stand together.

When we form connections across our differences, the northern Berkshire community is strengthened. Attacks like last night’s are rooted in fear of difference. The best antidote to that fear is to break down the barriers of not-knowing each other. And the best antidote to our own fears is to remind ourselves that we are not alone. That others care about us and will stand with us. That we are stronger together than we are alone.

(And — if these incidents are arousing fear and anxiety in you, please take care of yourself before you work on building bridges. “Put on your own oxygen mask first,” as airline flight attendants teach. I can recommend good therapists in the area if you are in need, and I am here if you want to talk about any of this. My hours will become more predictable once the school year begins again in a few days, but if you need me, reach out; I am here.)

At the City menorah lighting last week I said that to me the real miracle of Chanukah is the leap of faith. Someone chose to kindle the eternal lamp even though there wasn’t enough sanctified oil to last, and then somehow miraculously there was enough. The eternal light didn’t go out. It’s still burning. The light of our tradition still shines — in us. The light of hope shines in us too. In the words of Proverbs, our souls are God’s candles: it’s our job, with our actions and our mitzvot and our choices, to bring light to the world.

In the words of my friend and colleague Rabbi David Markus, “Where there is darkness, we ourselves must be the light.” These feel like dark times. We must be the light that the world needs. And when we shine, together our lights are more than the sum of their parts — like the blaze of the candles on a fully-illuminated chanukiyah, shining in our windows and across our social media feeds, proclaiming the miracle even now. Especially now.

May our chanukiyot shine brightly tonight. And may they illumine our hearts and souls so that our lives and our mitzvot and our actions in the world will shine ever-brighter.

With blessings of hope and light to all —

Rabbi Rachel

Originally posted at my From the Rabbi blog.

December 23, 2019

Chanukah gift

The closet in my study

holds picture frames, half-empty

boxes of stationery, old books,

pillows and blankets

for the guest bed. And tucked in

amid all of these, a small box

emblazoned Priority Mail,

addressed in your handwriting,

postmarked two years ago.

It slipped behind the quilts

and the crates of journals,

unseen and forgotten.

As I slice open the packing tape

I can scarcely breathe.

A letter you wrote to my son

for the last night of Chanukah

and some old coins -- a poem

and gelt, though I know

what in this box is truly gold.

Your words, your memory --

the oil that keeps on burning.

December 21, 2019

On the shortest day

I sit in the quiet.

I leaf through

your cookbooks.

I remember

how you loved

the beauty shop's bustle.

When night falls

I sing my way

through the door.

I want to say

look, Mom, we made it.

But you didn't.

You aren't struggling

anymore to breathe

as night closes in.

December 19, 2019

On silence, and speaking out, and bringing a better world

This morning with my Hasidut hevruta, R' Megan Doherty, I read a beautiful teaching from the Aish Kodesh (R' Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, the rabbi of Piaseczno, Poland -- later the rabbi of the Warsaw Ghetto.) Joseph's dream, in this week's parsha, depicts his brothers' sheaves bowing down to his in the field. But the Aish Kodesh reads it through a different lens. He draws on a Hebrew pun between "sheaf" and "muteness," and he explores what it means to be silenced. This speaks right to my heart.

Think about the difference between holding one's silence, and being silenced by an external force. There's a huge difference between holding silence for whatever reason(s), and having one's spirit be so broken by external circumstance that one cannot even begin to speak. Our job, in times of struggle, is to wait until our anger passes. And then we can say to ourselves: okay, I feel silenced by this circumstance, but I can still communicate. Even someone who has no (literal) voice can still communicate.

When the suffering of a whole community is such that everyone feels crushed and broken (in today's language, we might say traumatized or suffering from trauma), that's when we reach the circumstance alluded to in Joseph's dream of the sheaves. All of our sheaves are "bowing down," all of our souls feel silenced. But if one person can find the capacity to speak, then everyone else's silencing is lessened. If one person can find the inner strength to speak, everyone else can be strengthened thereby.

Righteous people want to seek serenity or tranquility in this world (notes Rashi) -- that's natural; of course we want and need to seek our own sense of peace. (Without some degree of peace and equanimity, we can't persist in times of sorrow or suffering.) But seeking inner peace isn't enough. God urges us not just to rest in the satisfaction of trusting that everything will be fine in the future somehow. Instead, we need to work to arouse heavenly mercy. We need to cry out to God to bring a better world.

That's what I took from the Aish Kodesh this week. And maybe, because we're not living in the Warsaw Ghetto like he was -- we have power to act in the world in ways that he didn't have -- we need to do something more external than pleading with God for a better world. We need to turn our hands to bringing "heavenly mercy" into the world. We need to act to create a world of safety, a world where no one is ground down by injustice or prejudice or unethical behavior, a world where no one is silenced.

Kein yehi ratzon -- may it be so, speedily and soon, amen.

December 18, 2019

Dear Mom (as Chanukah approaches)

Mom, you're on my mind as the the shortest day approaches. A few years ago you commented to me that it was almost the solstice and that you couldn't wait for the day when the balance would shift and we'd be moving into longer days. I was surprised and moved to hear you say that. It's something I never realized we had in common: a visceral dread of the darkest days of each year, a feeling of inchoate relief when we could tell ourselves that the sun is slowly returning. Probably we both carry some version of seasonal affective disorder in our bones, though you would never have claimed that label. You never wanted to call yourself sad in any way. You didn't even want to call yourself sick, even when the disease that claimed you had fully settled in.

Mom, you're on my mind as Chanukah approaches. A kaleidoscope of memories: the giant plexiglass dreidel you one year asked me to decorate, and the cornucopia of gifts that spilled forth from it. The year I wanted to light the Chanukah candles myself for the first time but got scared by the match, and dropped it, and left a burnt spot on the dining room carpet. Singing Maoz Tzur beside the flickering candles. Fast-forward: the year your father died during Chanukah, while I was in college. I had an a cappella concert that night, and the harmonies of "In Dulci Jubilo" brought me to tears. Fast-forward: the year my son was three and we first lit Chanukah candles together over Skype. Your visible sense of wonder at sharing that with him from afar.

It's so strange to me now: for all those years when I could have spoken to you any time I wanted, I so often didn't feel the need. And now that you're gone, the fact of your absence is a constant presence in my life. The fact that I can't tell you things -- or I can, but you can't answer. Maybe I'll be blessed with a dream. But it's not the same as the immediacy of being able to pick up a phone and tell you a story and hear your response. Every day when I go to send a photo of my son to his grandparents, my fingers want to type your email address first, even though you've been dead for nine months. We hadn't celebrated Chanukah together in ages. But the fact that you're not in this world anymore makes the approach of Chanukah feel different, this year.

What would you say if you could hear me? You'd tell me not to be maudlin. You'd point out that you're not suffering anymore. You'd remind me to enjoy what I have. You'd urge me to make hay while the sun shines, and to light candles against the season's darkness. To pour a glass of something tasty, and toast whatever sources of joy I can find. To set a pretty table at Chanukah, and gather friends for celebration. To enjoy my child's glee at opening gifts, winning at dreidel, unwrapping (and eating) chocolate gelt coin by coin. Mom, in your honor and in your memory I'm going to bring out the giant wooden chanukiyah that my brother made years ago. Its big bold tapers will blaze, just like they did in your house, and every night we will welcome more light.

December 16, 2019

New essay in Transformative Works and Cultures

I'm delighted to have a short piece in the latest issue of Transformative Works and Cultures. This issue (Vol. 31) is dedicated to the subject of fan fiction and ancient scribal cultures, and I'm looking forward to reading my way through it.

My piece is called Gender, voice, and canon. It explores classical, medieval, and late 20th-century feminist midrash as well as late 2oth-century Western media fandom. Here's the abstract:

The Jewish tradition of midrash (exegetical/interpretive fiction) parallels the fannish tradition of creating fan works in more ways than one. In the twentieth century, both contexts saw the rise of women's voices, shifting or commenting on androcentric canon—and in both contexts today, that gender binarism is giving way to a more complicated and multifaceted tapestry of priorities and voices.

And here's the article in html format for those who are so inclined. Deep thanks to the TWC editors for including my work!

December 15, 2019

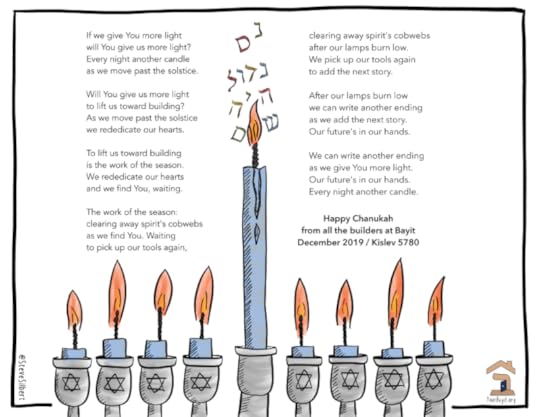

Happy Chanukah from the Builders at Bayit

Chag urim sameach

#BeALight this Chanukah as we

move past the solstice and

we rededicate our hearts.

poem by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat

illustration by Steve Silbert

Cross-posted from Bayit's Builders Blog. To stay up-to-date on happenings at Bayit, join our mailing list -- we won't spam you, I promise!

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers