Rachel Barenblat's Blog, page 109

February 29, 2016

Halaila hazeh (on this night)

After pyjamas, tooth brushing, and reading a book (which lately means him reading Press Here to me), we turn off the lights. Beneath the glowing stars on the ceiling we say prayers and sing our bedtime songs. This always includes the one-line shema, sung to the melody my mother taught me (which I now know to be by Sulzer.) This week I've started singing the first two of the Four Questions at bedtime, too.

Last year I sang the first question to him every night for a month and by Pesach he was able to belt it out proudly. This year I suggested he could learn the first two, and at first he balked. "I don't know," he said. "What if I can't do it?" I assured him that if he isn't comfortable singing them by Pesach, he won't have to. Grudgingly he admitted that I could sing them to him, but insisted he wouldn't sing along.

That was a few days ago. Then, one night as I began singing "Mah nishtanah," he joined in. To my surprise, he sang both of the questions with me, giggling all the way. When we were done I told him I was proud of him. He said he'd sing the questions to himself until he fell asleep. Then we sang the angel song. These days he usually chooses Shir Yaakov's melody over Carlebach's, though I love them both.

Then he said "Wait, before 'Goodnight You Moonlight Ladies' can I pray for one thing?"

"Of course," I said, startled.

"Thank You God for all the things You put in the world that make us feel better when we're not so happy," he said earnestly, and my heart grew three sizes at his spontaneous offering of prayer and his comfort with speaking not just about God but to God. "Amen," I said. "That's a beautiful prayer." (And I wondered what brought that on, though by then it was already well past official bedtime, so I didn't ask.)

Then I sang him our variation on James Taylor's "Sweet Baby James" (that's the aforementioned "moonlight ladies" lullaby, which we've been singing to him pretty much since the week he was born) and kissed him goodnight. Sure enough, when I walked by his room on my way upstairs, I heard him singing the Four Questions to himself. "Halaila hazeh, halaila hazeh..." On this night, on this night...

On this night, I am proud of my kid. On this night, I am humbled by my kid. On this night, I am so grateful for my kid.

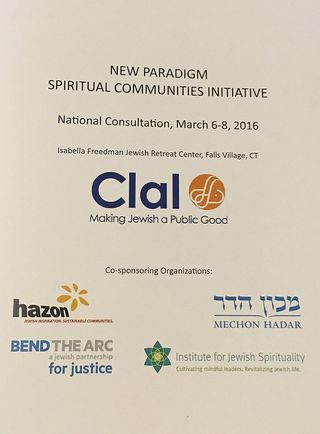

New Paradigm Spiritual Community Initiative

I'm at the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center today for the inaugural gathering of participants in a new program called the New Paradigm Spiritual Community Initiative.

I'm at the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center today for the inaugural gathering of participants in a new program called the New Paradigm Spiritual Community Initiative.

This is an invitation-only gathering for about fifty people working in a variety of different arenas, all of which could be described as "spiritual communities" in one way or another. Some of us serve congregations; others serve in other capacities. (And some, like me, do both. I'm there both as a pulpit rabbi and as co-chair of ALEPH.)

The NPSCI is intended to be a five-year project, and this initial "consultation" will help to set its direction.

Yesterday we began with some getting-to-know-each-other work. Each person took one minute to introduce ourselves to the room and say something about who we are, what we do, why we're here, what we're hoping for, etc. (And wow, this is quite a group!)

Then last night Rabbi Sid Schwarz (author of Jewish Megatrends: Charting the Course of the American Jewish Community) offered some framing remarks. Here are a few glimpses of what he said:

NPSCI aspires to support the development of spiritual communities that: a) are rooted in the wisdom and practice of Judaism, b) help people realize their full human potential; and c) inspire people to work for a more just and peaceful world...

When we are able to give people a sense of their purpose in the world, it is an experience of kedusha, holiness. Religions, at their best aspire to do both tzedek (justice) and kedusha (holiness), and often they fall short. They lose focus and perspective both on the means and the ends. But one of the things we in this room have in common is, we believe that Judaism has some chochmah, some wisdom, that can help create vibrant spiritual communities...

He talked about the need for innovation and R&D in Jewish life (a subject near and dear to our hearts in ALEPH!), the need to support and train those working within existing institutions on transformation from within, and the need to help people see that the paradigms in which we live are changing and that we need to shift our institutions to meet those changing paradigms. He asked:

Can we identify common elements that constitute a new paradigm for spiritual communities in America, and if so, what are the elements? What are the conditions for success? What best supports adaptation and innovation?

The question "what are the preconditions for spiritual innovation" is one of the core questions we're bringing to the ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour. Any time our core questions appear in other contexts, I feel affirmed in the fact that we're asking the right questions -- and glad to be able to wrestle with these big questions in the company of others for whom they are also meaningful. Another place of overlap between R' Sid's remarks and our conversations at ALEPH was this question he asked:

What would it be like if it were presumed that a Jewish spiritual community is one which both does the healing work people need in order to become whole, and one which raises people's sights about how to contribute to healing our broken world?

Today we're exploring different themes (wisdom, justice, covenental community, sacred purpose, arts), hearing from researchers from Harvard Divinity School who are working in this arena, and breaking into affinity groups (I'll be connecting with creative and innovative pulpit rabbis.)

The NPSCI is sponsored by Clal and spearheaded by Rabbi Sid Schwarz. Its other organizational co-sponsors are Hazon, Bend the Arc, Mechon Hadar, and the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. I'm not sure yet what exactly I'll be taking away from this gathering, but I can already tell that these are going to be thoughtful, interesting, meaningful conversations about the future of spiritual community. I'm glad to be here.

February 26, 2016

You who love my soul

One of my very favorite pieces of Friday night liturgy is a medieval love poem by R' Eliezer Azkiri called Yedid Nefesh. (There's a gorgeous setting of this poem on Nava Tehila's second album Libi Er / Waking Heart.) Our mystics imagined God as the cosmic Beloved, yearning for connection with creation even as we yearn for connection with divinity. Shabbat is when we and God meet in love.

One of my very favorite pieces of Friday night liturgy is a medieval love poem by R' Eliezer Azkiri called Yedid Nefesh. (There's a gorgeous setting of this poem on Nava Tehila's second album Libi Er / Waking Heart.) Our mystics imagined God as the cosmic Beloved, yearning for connection with creation even as we yearn for connection with divinity. Shabbat is when we and God meet in love.

At my shul we sometimes sing Yedid Nefesh in English, using Reb Zalman z"l's singable translation which captures much of the poetry of the Hebrew. "You who love my soul," the song begins, "sweet source of tenderness..." I am always moved by that way of describing the Holy One of Blessing: not as Lord, not as King (nor as Queen), but as the One Who loves us with infinite tenderness.

This love song imagines that as we welcome Shabbat, our tired souls can bathe in divine light and find comfort. By the end of the week we are worn out -- maybe in practical terms; maybe in heart or spirit. When we usher in Shabbat, we open ourselves to being healed. This song imagines us basking in divine light as one might bask in the presence of a beloved, deriving joy from the fact of that presence.

"My heart's desire is to harmonize with yours," writes R' Eliezer Azkiri (as rendered by R' Zalman z"l.) I love that line. I love the idea of singing in harmony with God, of having a heart which beats in harmony with God's. (The fact that I used to be a choral singer, and that I still derive tremendous joy from singing in harmony, probably contributes to how deeply that metaphor speaks to me.)

"As a deer thirsts for water, so my soul thirsts for you," writes the Psalmist. I know that feeling -- the feeling of a soul thirsty for sustenance, for connection. The feeling of a soul which yearns for God. I remember ten years ago, early in my rabbinic school journey, hearing one of my teachers describe me as "thirsty for connection with God." It was true then; it continues to be true now. It is core to who I am.

At its best, Shabbat offers me an opportunity to drink from that well of living waters, to satiate my thirst. No, that's not quite right. At my best, I'm able to take advantage of what Shabbat offers. The offer is always there; I'm the one who isn't always able to access it. Rabbi David Wolpe has written:

Friday night arrives. I know what my task is at this moment. I am to stop affecting the world and live in harmony with it. Even though I am a tangle of yearnings, on this day everything is to be perfect. I am to be satisfied with the many blessings that I have in my life. For once, I am to be at peace with the universe.

I find that idea incredibly compelling... and also often challenging. And I don't want to shame myself (or anyone else) for times when yearning, or mourning, or grief gets in the way of being able to experience the perfection which Shabbat is meant to encapsulate. But I take comfort in calling God "Beloved" -- whether or not I feel connected; whether or not I'm able to fully feel that "extra soul" of Shabbat; whether or not I can set aside my weekday strivings and be present with the perfection of what is.

February 24, 2016

New book on Jewish rites of death

One never knows when a blog post will go on to have currency and life, years after it was written. An essay of mine -- originally written for this blog -- has been adapted and reprinted in a beautiful new book called Jewish Rites of Death: Stories of Beauty and Transformation, edited by Richard A. Light. Here's how the editor describes the collection:

One never knows when a blog post will go on to have currency and life, years after it was written. An essay of mine -- originally written for this blog -- has been adapted and reprinted in a beautiful new book called Jewish Rites of Death: Stories of Beauty and Transformation, edited by Richard A. Light. Here's how the editor describes the collection:

This book is an introduction to an inter-world space, the boundary where death and life meet, the “space between worlds” that we encounter when we deal with the dead. We enter into it through a series of extraordinary processes in which the physical actions, the prayers, and the kavanah involved in Jewish death rituals open a window for us to glimpse this unique boundary. We can feel the experience of helping souls move from this world to the next as the book explores the practices and rituals of the Jewish tradition in preparing the dead for burial. It is an invitation to touch the fine line separating realms of existence.

Why should we put ourselves in the decidedly uncomfortable position of coming face to face with mortality? For those who engage in Jewish death rituals, the question is analogous to asking why we should see the Grand Canyon or a magnificent sunset first-hand. Helping a soul move between realms of existence inspires us, cultivates wonder, and expands our spiritual awareness. This book is dedicated to that liminal arena that allows us to peek through the doorway to heaven.

The volume moves through different stages: here are essays on aging and diminishment, accompanying the dying, accompanying the dead, mourning and grief, Jewish ideas of soul and afterlife, planning for death, and -- the section in which my piece appears -- taharah experiences, experiences of lovingly washing and preparing a body for burial. I've only just received my copy and begun reading what it contains, but I can already tell that this is an incredible collection. I'm planning to teach an adult education course on Jewish ideas about death and mourning at my synagogue this spring, and I think I've just found my text.

Rabbi Malka Drucker (who until recently served with me on the ALEPH board of directors, and who is a longtime friend, in addition to being the author of many excellent books) writes, "Rick Light has written a moving, important, and impassioned book on a subject that is no one's favorite. By looking through the God lens, he integrates death and life, and in so doing replaces fear with depth and meaning. He offers scholarly sources, intimate accounts of encounters with death from a variety of voices, and a well-organized, useful book for all who are planning to die -- and especially those who help others on their journeys."

And Rabbi Jack Riemer, editor of Jewish Reflections on Death and Jewish Insights on Death and Mourning, writes, "I don't usually say this about any book, but I believe that the vitality, the authenticity, and the future of Jewish life in America can be measured by how many people read this literally awesome book and learn to see both life and death in a new perspective as a result."

Jewish Rites of Death: Stories of Beauty and Transformation is available on Amazon for $23.95.

February 23, 2016

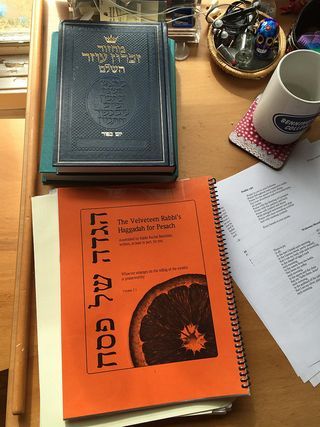

Let's do the time warp again

One of the surreal things about being a rabbi is that my work asks me to inhabit several different moments in time at once.

One of the surreal things about being a rabbi is that my work asks me to inhabit several different moments in time at once.

Purim is one month away, so I'm poking at the script for this year's Purimspiel. Pesach is two months away, and I've been working on creating a digital version of my haggadah (intended to be released as a set of shareable / editable slides, for those who might want to save paper by projecting the haggadah on a screen. Stay tuned; that's coming soon.) And I'm also working on revisions to my high holiday machzor, based on feedback from those who used the pilot editions.

What this means for me on a practical level is that both of my desks, the one at the synagogue and the one at home, are piled with liturgical materials which don't match each other. It also means that the mental melodies with which I spend my days are as likely to be high holiday nusach as they are to be "Adir Hu" from the Pesach seder. (Or, okay, in fairness -- they're also likely to be the Hamilton soundtrack. But when I'm not humming Hamilton, the liturgical soundtrack is set on random play.)

I like this sense of time warp. It feels a little bit like being in several places at once -- several headspaces, several heart-spaces. No moment in the Jewish year arises out of nowhere; each is connected with what will come after and what came before. There's something profoundly grounding for me in that awareness. The challenge is learning how to wholly inhabit this moment now while also remembering where I've been and where I have yet to go.

Wait. How can I remember where I have yet to go? I don't know what Pesach this year will hold! (Or Shavuot or the Days of Awe or anything else!) But I can re-inhabit what's come before. I imagine the Jewsh year as a long spiral staircase. Every year when we reach Pesach we're exactly above the Pesachim which came before, but at a different level. Somewhere in the overlayering of all of those Passover memories I can tap into the essence of the festival. That's what I can remember, even though I haven't yet experienced this year's iteration.

And that's part of what I love about having a mental liturgical-music soundtrack, because music is one of my deepest paths toward feeling . When I hear the lilt of Esther trope, I feel spring unfolding around me. When I hear the Pesach melodies of my childhood, I'm plugged right back in to the essence of Passover. When I hear the melodic mode of the Days of Awe, I'm instantly transported to that season of transformation. God, it is said, inhabits all of time and space at once. From God's vantage there is no "before" and "after" -- everything simply is. This interweaving of different musics is the closest I can get.

February 15, 2016

The obstacle is the door

I can't remember where I first heard the teaching from the Baal Shem Tov about lifting up the sparks of strange thoughts. Here's how that teaching goes:

I can't remember where I first heard the teaching from the Baal Shem Tov about lifting up the sparks of strange thoughts. Here's how that teaching goes:

It's human nature for one's mind to wander, even at times of contemplation or prayer. This is just what it's like to have a human brain. And then it's easy to imagine that one should castigate oneself for those thoughts which are getting in the way of connecting with God.

Not so, said the Baal Shem Tov. When those thoughts arise, our task isn't to banish them or to kick ourselves for having them, but to lift them up. Even an "unholy" thing has a pure spark of divinity within; find that spark and elevate it. (The binarism of holy / unholy may feel foreign or old-fashioned; just roll with it, because I think the teaching transcends the binarism.)

For instance, if one is distracted during prayer by the thought of a beautiful woman (of course he was speaking to men in a heteronormative context -- translate as needed into your own appropriate milieu), one shouldn't knock oneself for being distracted by that beauty. The thing to do instead is to lift up those sparks to God by thanking God for the God-given beauty which distracted you -- to find a way to make the distraction itself a path toward the One.

It's human nature to be constantly getting caught up in remembering the past (whether bitter or sweet), in anticipating the future (whether bitter or sweet), in telling oneself stories, in daydreaming about one's fears and one's hopes and one's desires. My meditation practice has revealed to me the constant chatter my monkey mind provides on all of those fronts. All of those can arise while I'm falling asleep, or driving the car, or washing dishes... and all of those can happen while I'm attempting to sit in meditation or to daven, too.

It's easy to kick myself for that; to think that if I really had good focus I would be able to keep that stuff out of my mind while in meditation or prayer. But the Baal Shem Tov teaches that there is holiness -- there is God -- even in those recurring thoughts which seem to get in the way of prayer. Indeed: the machshevot zarot ("strange" or "foreign" thoughts) which get in the way of prayer are themselves a doorway into deeper prayer. They offer me an opportunity to make prayer out of my very distractions.

The obstacle itself becomes the door. This is a classic Hasidic move. Instead of feeling that gashmiut (physicality) is something which keeps us from God, we can use our very embodiment to drive our service to the One. Instead of seeing our mis-steps (or "sins") as things which distance us from God, we can see them as the first step toward making teshuvah, turning toward God again -- because when we fall away from God, we stimulate our own yearning to rise and reconnect. (Tanya / Likkutei Amarim, ch. 7)

The obstacle itself becomes the door. Or, phrased another way (as I learned it from my teacher Jason Shinder of blessed memory), whatever gets in the way of the work is the work. (He was talking about poetry, but -- as I've said here many times before -- I find it a valuable teaching about spiritual life, too.) The hope or fear or yearning which gets in the way of my prayer can become the substrate of my prayer. The desires, anxieties, and thoughts which might appear to disconnect me from God become my way to connect.

February 10, 2016

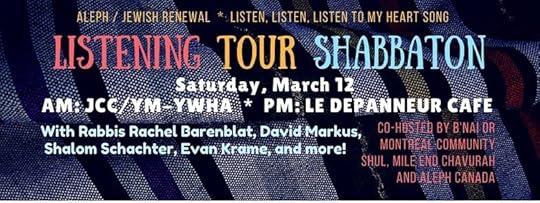

The ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour is Canada-bound

This winter's stops on the ALEPH / Jewish Renewal Listening Tour have been at conferences. In January we held one focus group for ALEPH ordination program students, followed by two open mike sessions at the OHALAH conference of Jewish Renewal clergy. In February we took advantage of spending a few days with our Rabbis Without Borders colleagues, and had some great conversations about ALEPH, Jewish Renewal, and the Jewish future while we were at Pearlstone. Now we're preparing for our two March stops, both of which will take us across the border to the north: we're Canada-bound!

Our Montreal Shabbaton on March 12 will be co-sponsored by B'nai Or Montreal Community Shul, Mile End Chavurah, and our colleagues at ALEPH Canada. (Here's the Facebook event page.) The plan calls for a morning / early afternoon program at the JCC/YM-YWHA, 5400 Westbury Avenue. We'll begin with a Shabbat morning service (in which Rabbi David and I will participate -- he's going to chant Torah, as Pekudei was his bar mitzvah portion!), a kiddush and vegetarian potluck lunch, and an open mike after lunch where we'll curate a conversation about hopes and dreams for the renewal of Judaism.

Our executive director Shoshanna Schechter-Shaffin will be with us, as will Rabbi Evan Krame (a member of the ALEPH Board) and Rabbi Shalom Schachter (son of Reb Zalman z"l), both of whom will also participate in the morning's service. (And we're always grateful when Board and staff are able to join us in our spiritual practice of receptive listening -- whether in person as we travel around the continent as life permits, or in the many listening tour sessions we've held via zoom videoconferencing. Alas, we're not able to visit everyone in person, so we are grateful for long-distance ways of listening.)

That evening we'll reconvene at Le Dépanneur Café, 206 Rue Bernard West, for havdalah. Then there will be a community cabaret, which promises to be terrific, though R' David and I will be quietly slipping out after havdalah and before the cabaret. (We've evolved a custom of spending Listening Tour Saturday nights post-havdalah together processing what we've learned and heard -- and also recording as much as we can remember of what was said, since we don't take notes on Shabbat.) Sunday morning we'll hold some meetings and conversations before we out-of-town guests hit the road to head home again.

If you are in or near Montreal, or are able to get there to join us, please do. We'd love to hear your thoughts, hopes, and dreams about ALEPH and Jewish Renewal's past, present, and future. (And if you're in or near Vancouver, stay tuned -- we'll be bringing the Listening Tour to Or Shalom over the weekend of March 26.)

Written with tears

I belong to a small group of local Jewish clergy which meets once a week at a coffee shop to study together, and for the last year or so we've been slowly working our way through Heschel's encyclopedic masterwork Heavenly Torah. Recently we read something about the final verses of the Torah which continues to reverberate in me.

I belong to a small group of local Jewish clergy which meets once a week at a coffee shop to study together, and for the last year or so we've been slowly working our way through Heschel's encyclopedic masterwork Heavenly Torah. Recently we read something about the final verses of the Torah which continues to reverberate in me.

The book of Deuteronomy ends with the death of Moses. This poses an interesting challenge for the classical tradition: if Torah was dictated verbatim by God to Moshe, then how can it contain verses about Moshe's death? How could Moses have told the story of his own death if it hadn't happened yet?

The tradition offers a variety of different answers, among them "he didn't write those last eight verses; Joshua did." But the answer I find most moving is that as Moshe heard about his own imminent passage out of this life, he wrote the final eight verses not with ink (or not only with ink) but with his tears.

Moses didn't get to cross into the Promised Land, but he did cross that threshold from this life into whatever comes next -- as everyone eventually must do. When he wrote the last verses of his story with his tears, what was he feeling? Were they tears of gratitude, or of longing? Tears of regret, or tears of joy?

Each of us, the tradition says, is to write a Torah. That's understood in a variety of ways: one should learn the scribal arts, one should fiscally support a Torah scribe, one should contribute commentary to the tapestry of tradition... and, perhaps, one should recognize consciously that one's life is a sacred text unfolding.

One of my favorite passages in this Heschel chapter holds that Moshe could have written the whole Torah with his tears, but then it would be too luminous for us to read. There are chapters in everyone's Torah of lived human experience which are written with tears -- tears of sorrow, and tears of gladness.

What would it be like to name those moments in our lives which are washed with tears not as something to be hidden away or avoided, but as luminous connections with the undercurrent of spirit which enlivens all things? What scripture might we write if we allowed ourselves access to the invisible ink of our cracked-open hearts?

February 5, 2016

Be there: on Mishpatim and presence

In this week's Torah portion, Moshe and Joshua and 70 elders have a mystical experience together. They ascend the mountain and behold a vision of God, under Whose feet there is the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, as pure as the very sky itself.

In this week's Torah portion, Moshe and Joshua and 70 elders have a mystical experience together. They ascend the mountain and behold a vision of God, under Whose feet there is the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, as pure as the very sky itself.

As if that weren't enough, then God says to Moshe. "Come up to Me on the mountain, and be there." And this time Moshe goes up on the mountain alone, and enters into the very cloud of God's presence, and remains there with God for forty days and nights.

This year the phrase והיה שם / "be there" leapt out at me. It seems superfluous. Wouldn't "come up to Me on the mountain" have been enough? Tradition teaches that every word in Torah carries meaning, which means there must be a reason for this phrase to be there. "Be there" suggests a different quality of being present.

It's one thing to climb the mountain. It's another thing entirely to really be present at the top -- or to really be present along the journey up or down. Anyone who meditates has probably noticed how hard it is to be in the moment. It's human nature to get caught up in the past or the future, to become so conscious of remembered wounds or joys (or anticipated ones) that we miss the now. Surely Moshe had that problem, just as much as you or I do. So God reminded him: come to Me, and be there.

I was talking about this with R' David Markus , and he asked whether I saw an anagram in the phrase והיה שם (be there.) I looked at it -- and suddenly saw the beautiful teaching he had wanted me to glimpse. Rearrange the letters of והיה ("and be"), and you get the four-letter Name of God, that Name which some consider too holy to speak (and others say we "speak" every time we breathe). When we can be there, then God is there. Making ourselves fully present is how we open up to encountering God.

Shabbat is a 25-hour-long opportunity to be there. On Shabbat, we're called to set aside our striving, to set aside the inclination to try to change things. We relinquish whatever happened last week: whether bitter or sweet, those days are over now. We resist anticipating whatever might happen during the new week to come: whether bitter or sweet, those days aren't here yet. Shabbat is the day we're given, each week, to be in the now. To let now be enough. To find the perfection in this very moment. To be there.

"Six days you shall labor and do all your work," Torah teaches, "but the seventh day is the Shabbat of Adonai your God; on it, you shall not do any work..." Maybe you recognize those words from the Shabbat lunchtime kiddush. The rabbinic text known as the Mekhilta asks, "Is it really possible to do all of one's work?" Isn't work, by its definition, something which can never entirely be completed? Rather, teaches the Mekhilta, on Shabbat we are called to rest as if all of our work were complete.

The Hasidic master known as the Sfat Emet teaches -- following on that idea from the Mekhilta -- that when a person truly stands still for Shabbat, peace and wholeness will descend on them, and it will be as if their work were complete. When we can relinquish workday consciousness, and our to-do lists, and the stories we tell ourselves about the future and the past -- when we can be there, as God instructed Moshe -- then we can touch perfect wholeness. Then it is as though our work were done. Then we can experience Shabbat as "a foretaste of the world to come."

The mystical vision of God atop a firmament which was like sapphire, as pure and clear as the very sky, may be beyond us. And the experience Moshe had atop the mountain, surrounded by a cloud of divine presence for forty days and nights, may be even more unimaginable. But we can all follow God's instruction to him, because we can all have the experience of Shabbat as a time to be there, to commit to being wholly present right here and right now. And right here, right now. And right here, right now.

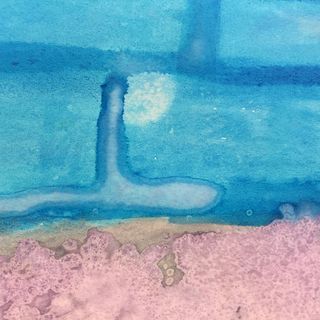

Image: a detail from a painting by Rabbi Pamela Jay Gottfried, in watercolor and salt.

This is the d'var Torah I offered at my shul yesterday morning.

February 4, 2016

Like sapphire

This week's Torah portion, Mishpatim, contains one of my favorite verses: כְּמַעֲשֵׂה לִבְנַת הַסַּפִּיר וּכְעֶצֶם הַשָּׁמַיִם לָטֹהַר. I love the verse (it's the second half of Exodus 24:10) because it's one which Nava Tehila has set to music. Had they not written this melody, I might never have paid much attention to these words... but because of this melodic setting, the verse has become one of my favorites in Torah.

If you don't see the embedded video, you can go directly to it at YouTube.

This verse comes from the scene where Moshe and the 70 elders, having ascended with God, are preparing for a banquet in heaven. Torah describes the floor where they are sitting as being like sapphire, though not actually sapphire. I think of this as a metaphor for how difficult it is to describe deep connection with God: our words always fail us. "It was like sapphire," we say, and words fall short.

Sometimes melody can deeply evoke an experience which doesn't quite translate into language. I don't know how Moshe and the elders might have tried to describe their ineffable experience with God once they got home again. Maybe if they could hear this melody and these harmonies, they would be satisfied that their experience had been communicated, with feeling and with heart if not with words.

Rachel Barenblat's Blog

- Rachel Barenblat's profile

- 6 followers