Patricia Meredith's Blog, page 3

September 1, 2023

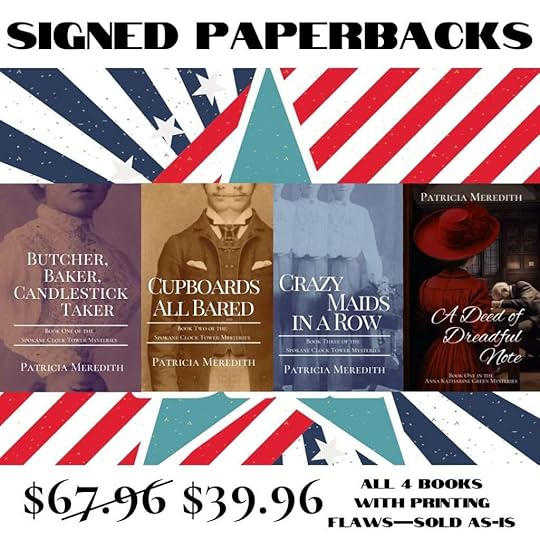

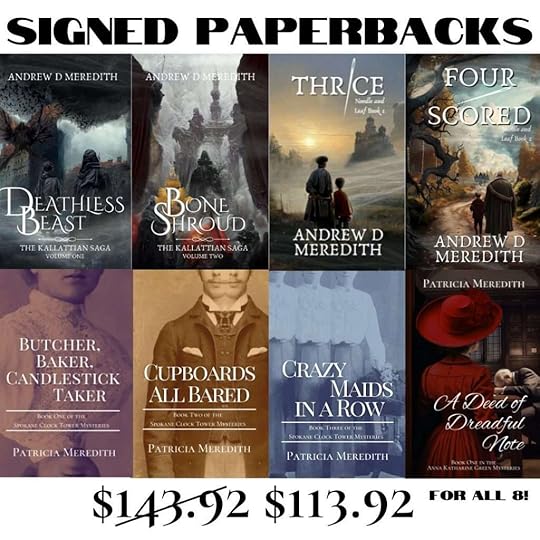

Labor Day Flash Sale!

Pick up all of our books in paperback format SIGNED at a great discount! While supplies last!

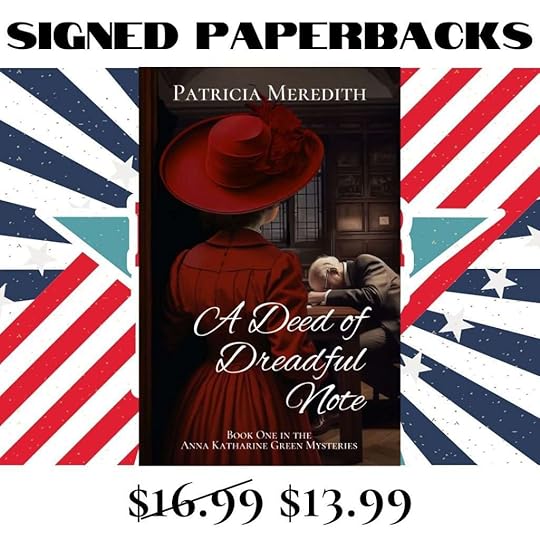

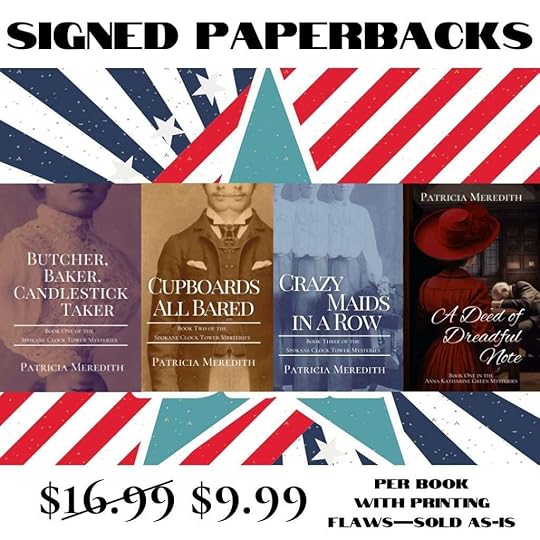

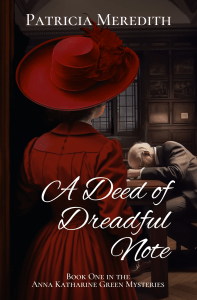

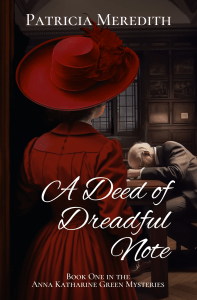

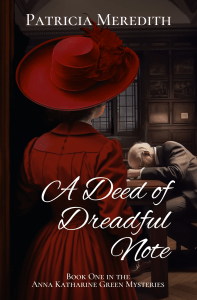

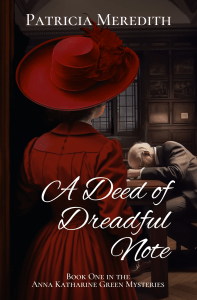

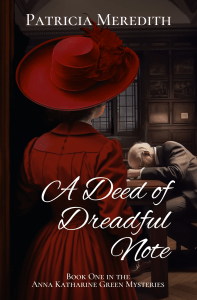

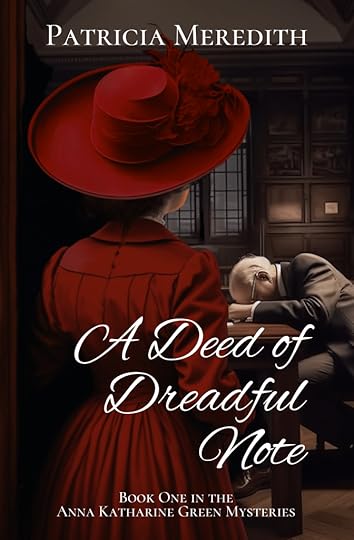

Historical Mystery by Patricia Meredith:*A Deed of Dreadful Note, first in a new series featuring Anna Katharine Green

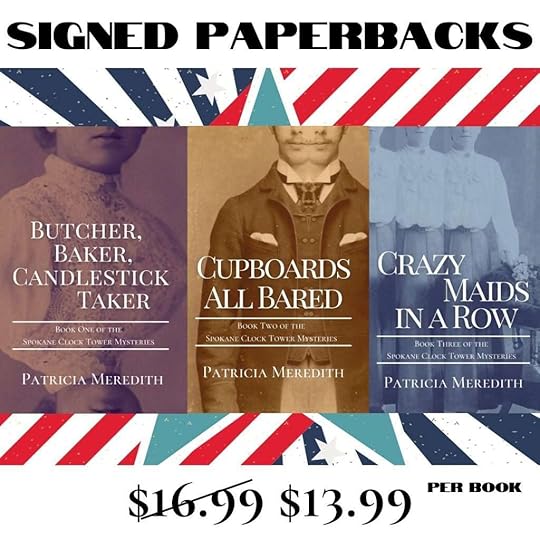

*Butcher, Baker, Candlestick Taker, first in the Spokane Clock Tower Mysteries set in 1901

*Cupboards All Bared, second in the Spokane Clock Tower Mysteries

*Crazy Maids in a Row, third in the Spokane Clock Tower Mysteries

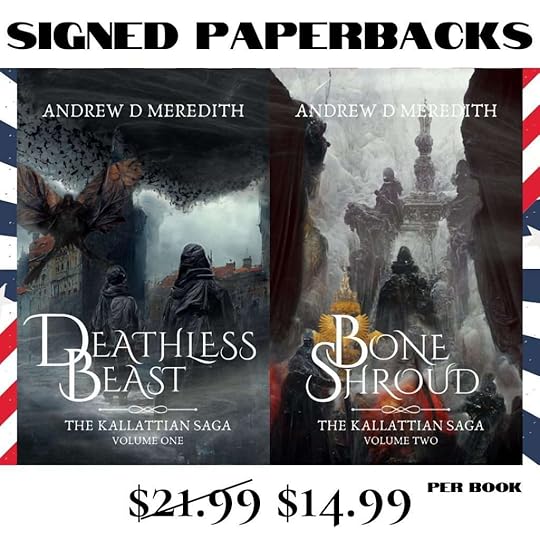

Epic Fantasy by Andrew D. Meredith:

Epic Fantasy by Andrew D. Meredith:*Deathless Beast, first in the Kallattian Saga

*Bone Shroud, second in the Kallattian Saga

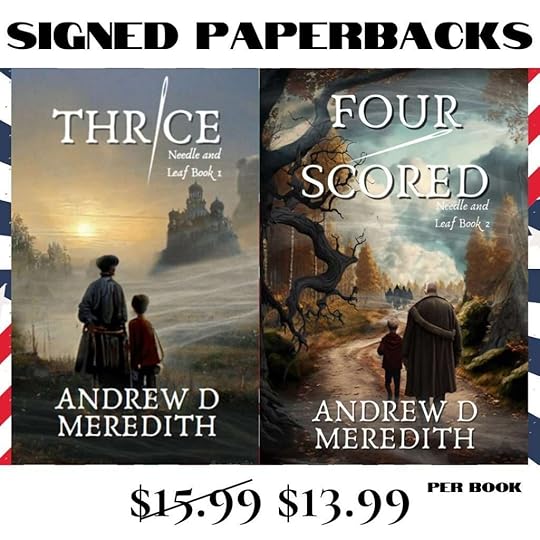

*Thrice, first in the Needle and Leaf series

*Four-Scored, second in the Needle and Leaf series

Be sure to follow us on social media as @pmeredithauthor and @andrewdmth to be the first to hear when future sales like this happen! Thank you for being a subscriber, and if you aren’t already, be sure to subscribe at our websites to receive free ebooks and more!

The post Labor Day Flash Sale! appeared first on Patricia Meredith, Author.

June 30, 2023

Goodreads Giveaway!

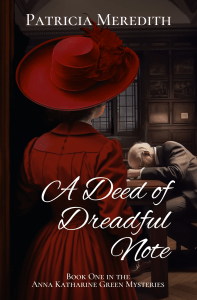

To celebrate my one month bookiversary, I’m having a Goodreads book giveaway for A Deed of Dreadful Note! First in a new series, I hope this book will introduce you to a fantastic forgotten female who was an Agatha Christie of her day!

Goodreads Book Giveaway A Deed of Dreadful Noteby Patricia Meredith

A Deed of Dreadful Noteby Patricia MeredithGiveaway ends July 14, 2023.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

If you’ve already read A Deed of Dreadful Note, be sure to leave me a review on Amazon or Goodreads to tell others how much you enjoyed the book!Fifteen years before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, Anna Katharine Green began writing The Leavenworth Case, inspiring the creation of detectives like Sherlock, Poirot, and Wimsey, as well as almost every device and convention we now recognize as standard in detective mystery fiction.

When her father’s client is found murdered, Anna takes up the call to prove innocent the young girl accused of the murder. The investigation inspires many of the events, characters, and descriptions that would later be published in her debut novel.

A love letter to mystery and writing itself, A Deed of Dreadful Note is an homage and reintroduction to an author who was the Agatha Christie of her time but a forgotten female today.

This book is a fictionalized account of how Anna Katharine Green’s first novel may have come to be…

Enter the Giveaway to win a free Kindle ebook copy OR Pick Up Your Personal Copy Now!Ebook—Amazon (other formats will be available in 3 months)

Audiobook—Wherever audiobooks are sold! Support local and order through Libro.fm!

Print—Order a signed copy from me here! Support local and ask your favorite independent bookstore to order in a copy!

Be sure to request the book through your local library, as well!

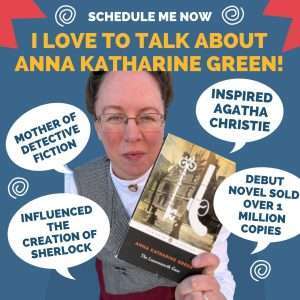

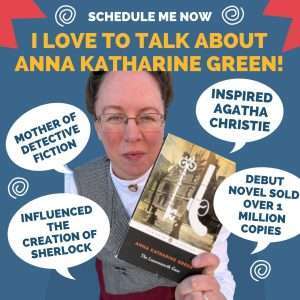

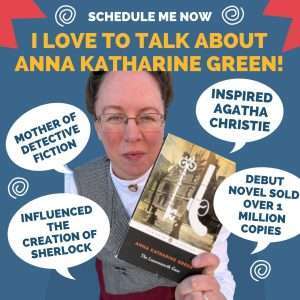

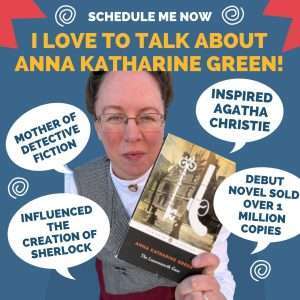

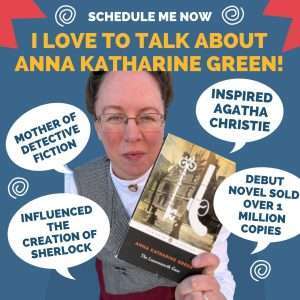

Interested in having me speak about Anna Katharine Green?If you haven’t noticed already, I love to talk about AKG!

Please email me at author(at)patricia-meredith.com, or DM me on Instagram or Facebook to check my availability near and far! I am available for both in-person or virtual engagements.

—Learn more about Anna Katharine Green—Watch my YouTube Channel playlist all about Anna Katharine Green.

Head here for a complete timeline of Anna Katharine Green and the History of Mystery Fiction.

A Deed of Dreadful Note is a piece of historical fiction, created by blending The Leavenworth Case with Anna’s personal history, recorded thoughts, and relationships since, as she said herself, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” Where possible, I have used Anna’s own words to capture the grace and wit with which she approached the world and her writing, in particular. I’ve now collected all of the quotes incorporated into the novel in one easy-to-access place!

AKG and I have a lot in common, it turns out! Watch my video and read this post to learn why I consider Anna Katharine Green my sister from another century.

Read Mary Hatch’s thoughts on her cousin and best friend Anna Katharine Green in an article originally published in 1889.

Find out what Anna Katharine Green thought was the answer to the question “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime?” by reading her article published in 1919.

November 11th is Anna Katharine Green’s birthday! Read this post to learn more about her impact on mystery fiction.

Find my full review, great quotes, and learn how Anna Katharine Green inspired Agatha Christie here from when I re-read The Clocks, and began to really research who this Green woman was.

Read my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read The Leavenworth Case.

Find my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read That Affair Next Door, the first Miss Butterworth case.

—Follow to Learn More—Sign up for my newsletter to be the first to hear all the details! You’ll also receive The Leavenworth Case, complete with my special introduction, for FREE for signing up! (Audiobook read by Andrew D. Meredith coming soon!)

Be sure to also follow me on Instagram and Facebook to hear the latest news concerning new book releases and events. And of course, subscribe to my YouTube channel!

You can also add my books to your Want to Read list on Goodreads! Follow my Author Page while you’re there so you’ll be notified when this new book is updated!

The post Goodreads Giveaway! appeared first on Patricia Meredith, Author.

June 15, 2023

“Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime” by Anna Katharine Green

By 1919, Anna Katharine Green was well on her way to earning the title “Mother of Detective Fiction” having successfully published 21 novels and two collections of poetry. At the age of 72, she knew a thing or three when it came to writing crime fiction and detective mystery.

Below you’ll find one of the most intriguing articles I’ve yet come across written by Anna Katharine Green. It includes several sections you may no doubt recognize if you’ve read A Deed of Dreadful Note…

“Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime” by Anna Katharine Green

“Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime” by Anna Katharine GreenPublished in American Magazine, February 1919

SINCE she wrote “The Leavenworth Case,” forty-two years ago Anna Katharine Green has published more than thirty novels and as many short stories, all dealing with mysterious crimes. She is the most famous author of detective stories in this country; and although she is 72 years old, she is still writing with remarkable keenness and power of invention. In private life she is Mrs. Charles Rohlfs, and much more interested in her husband and her two sons than in mysterious murders. Her home is in Buffalo, New York; and the lovely garden there — in which this picture is taken — is always planted and cared for with her own hands.

A Bad Sign to Watch for in Children

ANNA KATHARINE GREEN, the famous American writer of detective stories, says, in the article beginning on this page, that the motive behind nine tenths of the crime in the world is Selfishness.

“All the crimes committed to gain money are rooted in selfishness. So are the crimes people commit to be freed from some obligation or duty which they are too selfish to meet . . . . It is self, self, self, all the way through. If mothers and fathers would analyze crime as I have, it would be a terrible warning to them not to bring up their children to think that their desires and their feelings are the supreme consideration. Root out Self and you would practically eliminate crime.”

I HAVE been writing detective stories for about forty years; and in that time I have come to believe that practically everybody is interested in crime. You may say that you are not. But if I could watch your reading and listen to your conversation for a few months, or a year, I could prove to you that you are decidedly interested in crime, provided it has certain characteristics.

If a drunken negro kills another negro, or an Italian section hand stabs a fellow workman, you take no notice of it. But if a crime is committed by people you know, it blots out every other subject in your mind. If your next-door neighbor kills his wife, you are more interested in that than in anything else he might do.

Just suppose that your neighbor’s young daughter a caught in the act of shoplifting. Do you mean to say that you wouldn’t be incredibly more interested than you would if the young lady won the highest honors at school, or announced her engagement, or even died? If a young man in the next block should poison his sweetheart, wouldn’t you be more excited than if he won a decoration on the battlefield? I don’t think there is the slightest doubt of it.

Even of a crime is committed, not by someone we know personally, but by people like ourselves, or like the kind of people we want to be, we are intensely stirred. If a society woman shoots her husband, or a college student murders a young girl, or a big business man is killed by one of his competitors, the story of it — in ordinary times — is the first thing we read in the papers.

And if, in addition, there is some mystery about the motive, or about the act itself, we follow every detail of the case with what is commonly called “morbid curiosity.”

It isn’t morbid. It is perfectly natural and legitimate. These people are like us; or, as I said before, they are what we perhaps only dream of being — rich, cultivated, powerful. That they should commit murder, for instance, seems as strange as that we should ourselves. It is this strangeness that interests us.

It is as if a member of our own family should suddenly betray an unexpected and terrible trait; should do something so grotesquely horrible that we cannot reconcile it with what we know of them. Crime must touch our imagination by showing people, like ourselves, but incredibly transformed by some overwhelming motive.

The thing which interests us most in human beings is their emotions, especially their hidden emotions. We know a good deal about what they do; but we don’t know much about what they feel. And we are always curious to get below the surface and to find out what is actually going on in their hearts. Crime in people who are normal and have been trained to self-control must be the result of some tremendous emotion. It happens because of some great upheaval in human nature. No wonder we are interested in it.

There is another thing about crime which interests an amazing number of people. It helps to account for the fact that so many people read detective stories and follow the newspaper accounts of strange criminal cases. In reading an ordinary novel, they simply let the current of the story flow through their minds. But when they read a detective story, they are all the time figuring on the solution of the mystery, trying to guess how it is coming out. And they do the same thing when they follow a criminal case in the papers.

There is a rather general impression, I think, that men are more interested in this sort of thing than women are, but this is not my experience. And I believe that women are often more keen than men in sensing the solution of these mysteries. Women have more subtle intuitions than men have — a fact which should make them valuable in actual detective work.

I have often heard women say that they would like to be detectives; and they were women you could never have suspected of any such desire. I know of one woman, a member of the best society in one of our large cities, who helped in the investigation of a mysterious crime and was largely responsible for solving the case. Her name never appeared in connection with it, and her friends would be amazed if they knew she worked on it. She did it simply because she has the kind of mind which enjoys unraveling a mystery. And that kind of mind is by no means uncommon. The number of persons who have offered to help the Government in running down spies and uncovering plots would astonish you, I know, if the figures were given out. People love mystery. They like to think that they have “smelled a mouse.” In one city alone during the past year fifty-thousand “suspicious” incidents or persons were reported to the authorities. Of course, a patriotic desire to guard the country’s interests was partly responsible for this. But not altogether. There was also that common human interest in mystery and crime which is so strong in all of us.

I am constantly having proofs of the existence of this interest. Total strangers write to me about some “extraordinary crime” which has been committed in their own town. They are sure it will give me material for a “wonderful” book. As a rule, these letters only prove what I have been saying: that crime is intensely interesting to people, provided it comes close enough to them. For when people write me of some “extraordinary case” I almost invariably find that it is a very ordinary one indeed, without mystery in either the motive or the circumstances. The thing that made it interesting to my correspondent was that it came close to him or to her.

Then there are people who send me newspaper clippings. They are another proof that crime appeals to the human imagination; and from this source I do occasionally get valuable suggestions. My nephew once sent me a clipping which told of the deathbed confession of a physician in a small Western town. Years before, a woman patient of this doctor had died of some mysterious ailment and he had been so puzzled by it that the night after she was buried he went to the cemetery, bent on finding out the cause of her death.

He dug down until he reached the coffin, and was just about to open it, when he looked up and found himself face to face with the dead woman’s husband! In his fright at being discovered, he struck the man with a spade and killed him. Of course he was horrified by what he had done, and his only thought was to cover up his crime.

Can you guess what he did? Even in his terror he did not lose sight of the motive which had brought him there. He opened the coffin, took out the body of the woman, put the husband’s body there instead, filled up the grave, and carried the woman’s body home with him. Later, he buried it in his cellar.

The mystery of the man’s disappearance was never explained until the doctor confessed on his deathbed. I think they must have had very poor detectives. But they evidently accepted the natural theory that the man went off and committed suicide through grief over his wife’s death. The couple left two children and the doctor brought them up — which is an illustration of a point I want to make later.

THE interesting thing about my connection with this case is that three persons sent me copies of that clipping. At that time my books were published in Germany. But when this story was sent to my agents there, they wrote that they had just accepted a novel dealing with the same incident. And my agents in England wrote that they, too, had just produced a book on that theme. Evidently that clipping had traveled pretty widely. It is an example of the universal appeal of certain crimes.

Normal people are not so much interested in crime itself as they are in the motive behind the act, or in the person committing it, or in the mystery surrounding it, or in some extraordinary circumstance connected with it. To be interested simply in crime, merely as crime, is either morbid or scientific. Most of us are neither. We are just human; and with us it is the motive which rouses our curiosity. Acts are not especially interesting in themselves. But the motives back of the commonest act may be tremendously interesting. Apply this to your own lives and see if it is not true.

For example, suppose your daughter goes to see a friend in the evening and, instead of taking the shortest way, follows some roundabout route. If she does this simply because she wants fresh air and exercise, that isn’t interesting. But if she does it because she wanes to meet her lover, who has been forbidden the house, her simple act is at once full of exciting possibilities. If you go into the city to do some shopping, that is a very commonplace thing. But if you are going there to meet your son, in secret, and to give him your savings so that he may replace money he has stolen from his employer, your little journey is the most thrilling one you ever have taken.

AND consider his own act. If he tells you that he took the money to bet on the races, you are shocked and grieved, but there is no mystery in it. If, however, he will not tell you why he did it, if he seems haunted by some strange fear which he will not explain to you, his motive at once looms larger than the act itself. Why did he want the money? What did he do with it? What sinister influence is proving stronger than all your training?

In nine times out of ten the motive can be put down as Selfishness. It takes many forms. It is responsible for those crimes which have money as their object. The young man who cannot wait for some relative to die so that he may inherit property; the people who murder in order to collect life insurance; those who kill in order to rob; all the crimes committed to gain money — theft, embezzlement, forgery — all of these are rooted in selfishness, in greed for one’s own self.

So are the crimes people commit to be freed from some obligation or duty which they are too selfish to meet. Men kill their wives, women kill their husbands, because they want liberty to go with someone else. Young men kill the girls they have betrayed, because they want to escape the situation they have brought about. Or a man kills someone who possesses some secret which would disgrace the murderer if it were known. Jealous men, jealous women, kill because they can’t have the love they want. And they kill because they want revenge.

It is self, self, self, all the way through. If mothers and fathers would analyze crime as I have, it would be a terrible warning to them not to bring up their children to think that their desires and their feelings are the supreme consideration. Root out Self and you would practically eliminate crime. Even those acts which are committed in sudden passion can be laid to the same fundamental cause — lack of training which makes us tolerant of things contrary to our convenience or liking.

CRIMES which are the result of sudden passion are less “interesting” than premeditated ones, because real motive is lacking. That is why I seldom use them in my books. But there may be poignant situations following such an act.

In “Dark Hollow,” for example, I took the case of the judge who, in a fit of anger, has killed a man twenty years before the story opens. But I make the man a close friend of the murderer. No one knows that the judge is a real criminal. He presides at the trial of a man who is wrongly accused; and when the man is convicted, he — the real murderer — pronounces sentence. He lacks courage to take the punishment himself; but he does penance secretly, for twenty years, in a convict’s cell of his own building in his house.

This attempt to compromise with conscience is absolutely true to life. That is the point I referred to in the case of the doctor who brought up the children of the man he murdered. That might have been a significant clue to a detective with imagination. I don’t mean that all kindhearted people who take care of the children of mysteriously missing parents are to be suspected of murder! I only say that this might have been an important point in that case.

But it seems tome that the ordinary detective is not gifted with an imagination. I am judging only by results, for I have known personally only one detective. Years ago, the man who was then chief of police in New York City was a friend of my father’s, and I remember his driving us out one day to his home on Long Island. On the way we passed a house with a plank nailed across the front door. As people were evidently living there, my imagination immediately seized on that curious feature and I asked the chief about it. He must have passed the place dozens of times. Yet apparently he had not felt the slightest curiosity about it. The barred door did not necessarily indicate crime. But the trained detective mind should be on the alert for the unusual, the mysterious, and should at least be curious about the motive behind the mystery. To this day, that barred door appeals to my imagination.

Certain houses, certain spots, have an atmosphere of mystery. And you cannot always trace it to a definite detail, such as that door. More often it is only a feeling. Just as some houses give you a feeling of comfort, others give you one of dread. Haven’t you ever exclaimed, “That house looks as if a crime had been committed there!”

I believe the impression can be accounted for — sometimes at least. The scene of a crime is scarcely a place loved by the people concerned. Yet it may be the old home of a family and they cannot, or will not, abandon it. So they go on living there. But the attention given it is an austere and unwilling thing. You feel it and you come under the same spell of repulsion which the people themselves must have.

Then there are the freak houses which always excite our curiosity. The house in “Dark Hollow” in which the judge tried to expiate his crime was enclosed in a double tight-board fence. I suppose people thought I invented that detail. Yet it was taken from real life. I have found that the incidents in books which people pick out as improbable are the very ones which are founded on fact. Truth is stranger than fiction.

Murder is the most interesting crime in the whole category; and for two reasons: First, it is the supreme crime. It is the only irreparable one. It may be true that he who filches from you your good name robs you of something better than life itself. But you always have the chance of getting your good name back again. Robbery, forgery, kidnapping — none of these is absolutely irretrievable. But a life that is taken can never be restored. There is complete finality about such a crime. And as the motive must be correspondingly overwhelming, it is, therefore, of the most vital interest.

THE other reason why murder is the most interesting theme for a mystery story is that the act involves two persons. They alone have held the explanation. And one of them has been silenced forever! That lifeless body, with its lips sealed on the great secret, becomes an object of thrilling interest. There is no other crime in which you have that situation. That in itself appeals with tremendous force to your imagination. You feel that you must know what those silent lips would tell if they could only speak. And when, in the story, you come to the actual telling of just how the murder was committed, you read it as if it were being spoken by the dead man himself. Isn’t that true? Haven’t you felt, when reading, perhaps, the account of a mysterious murder: “Oh! if only the dead could speak!” And you try to think, to imagine, what they would have to tell.

There is an old saying that “Murder will out;” and it has been confirmed in the vast majority of cases. Even when the criminal has not been convicted in the courts, I believe you would find, if you knew the inner history of these cases, that he is known to certain persons. I have in mind now certain murders, sensational trials, where the accused persons were not convicted; but there is no doubt in my mind as to their guilt.

However, I think it is very rare for a murderer to escape detection. No matter how carefully a crime may be planned, or covered up, the criminal almost invariably forgets some significant detail. Curiously enough, Nature herself seems to be in league with circumstances to convict him. She puts a little muddy spot in his path so that he leaves a footprint. Or she blows a curtain aside at the very instant that a passer-by can catch a glimpse of his face. Or she twists the current of a stream so that some evidence of his guilt floats to the surface. Crime is contrary to Nature. And Nature often seems bent on punishing it.

In writing detective stories, the less one resorts to arbitrary helps in the mystery, the better. I mean that people are not interested in a crime that depends on some imaginary mechanical device, some unknown poison, or some legendary animal. To resort to such expedients for your mystery is a weakness. To employ imagination in making use of natural laws, however, is another matter.

Take the famous French story of a man found in a studio with a bullet through his heart. It was supposed to be a mysterious murder. But the solution was that a manikin, which the artist used as a model in painting, had held a pistol — placed there by the artist himself — in its wooden hand; that there was a leak in the skylight; and that the water dropping on the mechanical hand had caused the fingers to contract, pulling the trigger. The pistol happened to be pointed at the man asleep on the couch and the bullet went through his heart. The pistol dropped on the floor. The story was an ingenious one, but the interest in it was chiefly one of curiosity, because there was no motive, no deep human feeling there.

I HAVE been asked whether I am not afraid that real criminals will study my stories to get pointers on committing and concealing crimes. No, I am not; because I do not put the emphasis on the manner of the act, but on the motives behind it and on the novel and strange situations which come in working out the mystery.

Once I did write a story about which I had anxious moments after it was published. In that story a murder was committed with a hatpin; and at that time I had never heard of such a case. It worried me lest I had suggested a new way of crime. When I found that murders had actually been committed in that way before I wrote the book, I was intensely relieved. That was the only time I ever suggested what I thought was a new instrument for crime, and I shall never do it again.

It is curious how the “mechanism” of detective stories has changed since I began writing them. Sometimes I think that no one can appreciate, as the writer of detective stories does, the march of science in the past four decades. For he must make use of every one of these modern inventions in building up his plots. When I began writing, we used gas for illumination, carriages for riding, and so on. Now we have electricity, telephones, wireless telegraph, automobiles, airplanes, submarines, motor boats, and so on. Do you realize how completely the machinery of life has changed in forty years? You would if you had been writing mystery novels.

But motives do not change! Character remains the same — built of the eternal qualities of good and evil. And the great truth which I have learned through my study of crime and its motives is that evil qualities are inevitably those which center in Self. They are overweening ambition, avarice, covetousness, jealousy, revenge, passion. Someone of these is in command when the ship of your life drives on to the rocks. Wipe out Self, and you will wipe out crime.

(**Please note that this article was originally published in 1919, so I apologize if there is anything offensive or irreverent in her terminology when referencing certain people.)

Pick Up a Copy of A Deed of Dreadful Note!

Pick Up a Copy of A Deed of Dreadful Note!A Deed of Dreadful Note, first in the Anna Katharine Green Mysteries, is the first and only historical fiction ever written featuring the Mother of Detective Fiction!

Fifteen years before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, Anna Katharine Green began writing The Leavenworth Case, inspiring the creation of detectives like Sherlock, Poirot, and Wimsey, as well as almost every device and convention we now recognize as standard in detective mystery fiction.

When her father’s client is found murdered, Anna takes up the call to prove innocent the young girl accused of the murder. The investigation inspires many of the events, characters, and descriptions that would later be published in her debut novel.

A love letter to mystery and writing itself, A Deed of Dreadful Note is an homage and reintroduction to an author who was the Agatha Christie of her time but a forgotten female today.

This book is a fictionalized account of how Anna Katharine Green’s first novel may have come to be…

NOW AVAILABLE!

Ebook—Amazon (other formats will be available in 3 months)

Audiobook—Wherever audiobooks are sold! Support local and order through Libro.fm!

Print—Order a signed copy from me here! Support local and ask your favorite independent bookstore to order in a copy!

Be sure to request the book through your local library, as well!

Interested in having me speak about Anna Katharine Green?If you haven’t noticed already, I love to talk about AKG!

Please email me at author(at)patricia-meredith.com, or DM me on Instagram or Facebook to check my availability near and far! I am available for both in-person or virtual engagements.

—Learn more about Anna Katharine Green—Watch my YouTube Channel playlist all about Anna Katharine Green.

Head here for a complete timeline of Anna Katharine Green and the History of Mystery Fiction.

AKG and I have a lot in common, it turns out! Watch my video and read this post to learn why I consider Anna Katharine Green my sister from another century.

November 11th is Anna Katharine Green’s birthday! Read this post to learn more about her impact on mystery fiction.

Find my full review, great quotes, and learn how Anna Katharine Green inspired Agatha Christie here from when I re-read The Clocks, and began to really research who this Green woman was.

Read my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read The Leavenworth Case.

Find my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read That Affair Next Door, the first Miss Butterworth case.

—Follow Me Here—Sign up for my newsletter to be the first to hear all the details! You’ll also receive The Leavenworth Case, complete with my special introduction, for FREE for signing up! (Audiobook read by Andrew D. Meredith coming soon!)

Be sure to also follow me on Instagram and Facebook to hear the latest news concerning new book releases and events. And of course, subscribe to my YouTube channel!

You can also add my books to your Want to Read list on Goodreads! Follow my Author Page while you’re there so you’ll be notified when this new book is updated! You can add A Deed of Dreadful Noteto your Want to Read list here!

The post “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime” by Anna Katharine Green appeared first on Patricia Meredith, Author.

June 8, 2023

Mary Hatch and Anna Katharine Green

When Anna Katharine Green had the dream that would inspire the writing of The Leavenworth Case, her debut novel, the first person she wrote to was Mary Hatch:

“The other night I had a wonderful dream, which has impressed a story on my mind.… It is so passionate, so strong, so subtle, so dread, dark, and heart-rending, it ought to be written with fire and blood.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch

Mary Hatch was Anna’s “cousin” and her dearest friend in the world. She’d first met Mary Platt, later Mrs. Antipas Hatch, upon her return from college. As I write in A Deed of Dreadful Note, although she was Anna’s brother’s wife’s cousin, Anna often referred to Mary as “my cousin” for simplicity’s sake.

Below you’ll find an article written by Mary Hatch about Anna Katharine Green. I hope you’ll find it engaging and a perfect example of the sorts of delightful articles I found to assist me in my research and the writing of A Deed of Dreadful Note.

“An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch

“An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. HatchPublished in The Daily Inter Ocean, July 21, 1889

Anna Katherine Green, the Author of “The Leavenworth Case” and Other Detective Novels.

Her First Story and Its Popularity — Extracts from Her Letters About Her Books.

How She Works — Two Years in Planning One of Her Successful Tales.

When the doughty Knickerbocker historian “voyaged to Haverstraw beyond the great waters of the Tappan Zee,” making classic as he passed the Palisades, Sleepy Hollow, and the profane regions of Spuyten Duyvil and Hell’s Gate, I suppose his mood may have been scarcely more adventurous than my own when, twenty years ago, I stood on the little Hudson steamer, the Chrystenah, bound for the self-same Haverstraw. It was almost my first trip to the great world and I was to mee that rara avis, an embryo authoress, who never doubted her ultimate success, though she had never had a line of her writings published outside her college paper.

As the Chrystenah swept up to the landing a tall, graceful girl, dressed in gray, with red berries in her hat, came forward to meet us, my cousin (her brother’s wife) and I.

She was scarcely older than myself, if of more assured womanhood. No premonition of friendship touched our first meeting, and I was quote content to be a listener, quiet and unused to her bright girlish chatter, as she related to my companion incidents and bits of travel; for she had just returned to Haverstraw from Poultney, Vt., the seat of Ripley College, of which she was a graduate.

We were always together in the months which followed, for a strong and enduring friendship, founded upon similarity of tastes and dissimilarity of temperaments, sprang up between us; and we shared the same room and the same pursuits. I soon learned that Miss Green had been writing tales and verses since she was 11. Ralph Waldo Emerson had just written her a letter, and so had Mr. Fields, and she was content to bide her time, which she knew would come, although her manuscripts came back to her with mathematical precision. A critic had said to her, “Keep out of the magazines if you can.” “If he had only known how hard I had tried to get into them,” she said, laughingly.

The girlish larks we indulged in, the costumes, quaint, ugly and curious, we dressed up in, the walks we took past the glaring brick yards, the outre characters we filched for our stories, the plans we sketched, the hopes we matured, the story we wrote together in which were forecast, on her part, the Leavenworth heroines—all this wells up from the fountain of memory as I write, but I pass it by for other matters.

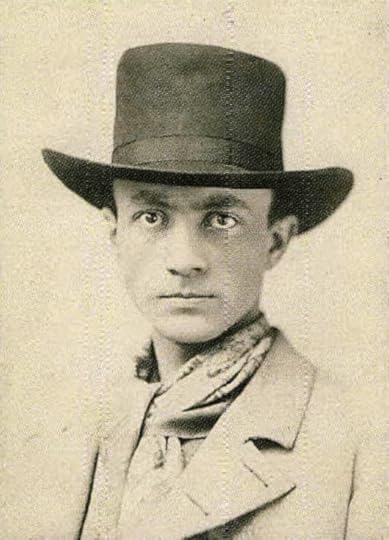

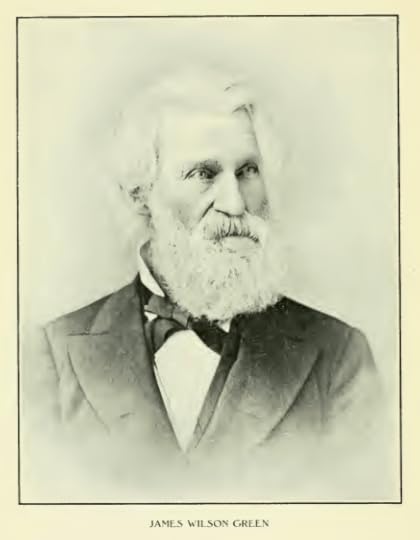

Anna Katharine Green comes of a notable East Haddam, Conn., family. She is the daughter of James Wilson Green, at one time editor of the National Era (New York), and a lawyer of repute. From him undoubtedly his daughter inherits her legal turn of mind as evinced in her novels. Born under the very shadow of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, her environments may have fostered her literary aspirations, for they were manifested at an early age, and in as pronounced a manner as ever fell to the lot of genius. “After the removal of the family to Buffalo,” says Mr. Bigelow in the Magazine of Poetry, “when she was a mere child, she would walk the streets alone and recite to herself stories and verses of her own contriving.”

Many people believed “The Leavenworth Case” to have been her first start in the craft, but such was not the case. She served her apprenticeship in writing poetry and thus learned the art of expressing herself with grace, accuracy, and poetic finish. A prominent critic has lately recommended the same course to all writers of prose. Miss Green wrote all the verse which forms the two volumes of her published poetry before writing a single novel, and in those days called herself a poet only. “I eschew prose. Poetry is my forte; story telling is not possible to me, and now lies in an ignominious corner of my drawer,” she wrote the March following my return from New York.

“I am still writing with a good hope in my heart,” “I write from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.” “I have not cut 500 lines.” “Last night a thought came to me and I wrote it down in the night.” For a young writer these extracts from her letters evince uncommon labor and care and a patience rare as remarkable.

She continued to write poetry—fiery, passionate verse, that thrilled the heart of public and critic, at last winning recognition as such poetry must. Her poems appeared in the Independent, the Century (then Scribner’s Magazine), Lippincott’s, and other periodicals. I will transcribe a little poem she sent me at this time, and which she afterward copied on the fly leaf of my volume of “The Leavenworth Case.”

SHADOWS

“A zephyr stirs the maple trees,

And straightway o’er the grass

The shadows of their branches shift;

Shift, Love, but do not pass.

So, though with time a change may come

Within my steadfast heart,

The shadow of thy form may stir,

But can not, Love, depart.”

Can anything be more exquisite than these lines?

She sent from time to time extracts from all her long poems. To meet them between book covers was like greeting friends from whom one has long been severed, and in looking over her letters it was an actual pleasure to re-read her old-time words regarding her work, re-baptized for the public. “I am amusing myself by seeing how much I can put into eight lines,” she writes of “Pearls and Shadows.” Of “Paul Isham” “I shall not be surprised if you like it best of all.” When “Resifi’s Daughter” was published, three years ago, she wrote concerning it, “It is, I hope, the best piece of writingI have ever done,” but years before I had become familiar with the more notable parts. The masterpiece of the collection of poems is “The Tragedy of Sedan,” a fiery, rushing, seething, heart-rending poem. You are hurried through with bated breath and fast-beating heart. Sustained action! Why, it is sustained tempest.

“The Defense of the Bride” (and other poems) and “Resifi’s Daughter” almost upon publication took their place as successful, even without a dissenting voice from the critics, but instead much that was cheering. Harper’s Magazine characterized them as “vigorous productions,” possessing “masculine force and brevity,” etc. To know much of one thing one must be content to know less of others, and often to go through life with a mind veiled to the commoner things. The active brain of Miss Green holds many a talent which, better tended, might have blossomed into fame; but all has been cheerfully offered to the shrine of her muse, to feed the fires of her literary genius. An author can do no less, for he has as competitors not such as meet other craftsmen, those of his own day, his own city—maybe his own country, but authors of all times and climes, living and dead. A picture once painted stands forever and aye as an original. A book multiplies long after its creator is dead, and blocks the way before the new aspirant of literature. “But art life has its advantages,” she writes Aug. 22, 1880, “in what it does for our souls and our emotions. The world means more to the artist than to other people, for he is constantly following out the delicate threads of though, feeling, and action, tangling and untangling them, working himself back and forth through the labyrinth of circumstance and event, searching for the secret heart of all; the explanation of all, its source, power, and meaning.”

The dividing line between poetry and prose was reached in 1876, I think, when she wrote to me thus: “The other night I had a wonderful dream, which has impressed a story on my mind. * * * It is so passionate, so strong, so subtle, so dread, dark, and heart-rending, it ought to be written with fire and blood. It will require all my enthusiasm, study and power, and then I may fall short, but I believe I shall sometime try. Perhaps it is somewhat sensational, but I hope by characterization and earnestness to lift it to a higher ground.”

Faraday, the noted philosopher, is quoted as saying, in regard to novels, “I like the stirring ones, with plenty of life, plenty of action and very little philosophy. I want the novelist to supply me with incident and change of scene and to give me an interest outside of my own immediate pursuits.” One of Faraday’s favorite novels was “Jane Eyre,” “where a man,” he says, “keeps his mad wife at the top of his house. It is very clever and keeps you awake.”

This is the idea no doubt of many less distinguished people, and accounts for the popularity of writers like Charles Read, Wilkie Collins, Poe, Gaboriau, and Miss Green. People like to be kept awake, taken out of their immediate pursuits; and considered in this light, a work like “The Leavenworth Case” must bear off the palm before one of Howell’s or James’, which are the natural concomitant of leisure and culture, but not suited to the busy, who in an hour of entertainment seek the cup of self-forgetting excitement. Miss Green has received scores of letters which attest to the truth of these premises.

“It was written for the populace,” she wrote, “and while I can not help throwing into it some of my enthusiasm, I do not want you to think I have any hopes for it in the way of giving me favor. I had to stop and throw out this story before I could get leave to settle down to my life work of writing poetry. * * It absorbs me, and I can not help thinking it worth the labor bestowed upon it.”

“I never expected to be a prose writer,” she says later, on the eve of its publication, “and I find I have astonished my friends very much. I hope it will be a reasonable success if only to pave the way for my poems. The name of my novel is ‘The Leavenworth Case: a Lawyer’s Story.’”

It was accepted under the most favorable conditions by the first publishers who saw it, Messrs. Putnam’s Sons.

My copy arrived Thanksgiving Day, I recollect. I was astonished and delighted. I wrote and told her so, and she replied, “I was afraid it outre character would strike you unfavorably.”

From the moment of its appearance her success was assured; and at this point, it is interesting to note the author’s comments on her work—reasonable success, outre character. These were her words concerning the famous “Leavenworth Case.”

In another letter she wrote, “One ought not to expect much from a first effort. If I make anything of a start I shall do well.” As a pleasing contrast to her own estimate I must mention the fact that of sixty reviews which I read only one was unfavorable.

Of “A Strange Disappearance” she writes under date of Dec. 18, 1879: “My new book is out; my other one preparing for the stage, and all uncertain if success will attend the venture. As to ‘A Strange Disappearance’ I am quote encouraged, the first edition being nearly exhausted the first week. But what will the critics say? Ah, what!”

“I presume you have read my book,” she writes later. “You will see that it makes no pretensions to be as elaborate as the other. The character of Luttra is the story’s excuse,” and Luttra would have been the title had her publishers approved.

The “Sword of Damocles” made its first appearance in 1881. “It is the fruit of much thought,” she wrote. “I conceived its plot and general plan immediately after the publication of ‘The Leavenworth Case,’ and then gave it two years of thought before putting pen to paper. The work contains two plots, and the characters range from the president of a bank to the most desparate of castaways. The first chapters have gone to press, and the last quarter of the book has not even been written. You see how I am driven and what a responsibility rests upon me.”

The reviews of the new book were for the most part satisfactory, but it never possessed the popularity of the other two, although and intensity of life runs through the events and it has many strong passages.

Her next long work was “Hand and Ring,” which first made its appearance in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and was afterward brought out by the Putnams. The people who read it with such avidity little understood the confusing nature of the author’s task. “I am at work upon four parts of it at once,” she wrote. All through it she was driven to the last extremity, writing the last chapters for Leslie, arranging the first ones for the Putnams, and correcting proof for both, and this in hot July. “It seems strange not to be among the groves and trees, but,” she adds, gleefully, “I mean to have my outing yet.” Her books have appeared at quite regular intervals, ten in eleven years. She has just completed a novelette, and is engaged upon a longer work.

The same large scope, range, and intensity of feeling mark her works, whether verse or prose; the same directness, power, and dramatic finish; no magrims of the brain but fully developed, they invariably possess a forcible mastery of the subject. She deals with action, things, and motions. Humanity seems to her of more consequence than the world it exists in. If there is a lack in her prose it is in the descriptions of scenery; if superabundance in her poetry it is in the “fine excess,” of which, however, George Eliot says “we have need.” If in Miss Green’s later works one misses something of the intensity and dramatic interest of her earlier ones, there is noticeable on the other hand a more masterly characterization, a subtler rendering of motive. Of her methods of work she says: “In the first place, I do not create a story or plot—both come to me. I can not write unless I am vitally interested. My imagination may be stirred by some detail or situation, but until I am thoroughly acquainted with my people, their environment, the thoughts they think, the glances they give, in fact every little element that goes to make up their relationship to the drama in which they are cast, I sit and think, feel and dream, but do not write. * * * A sentence in the first chapter is conceived and wrought out to suit possibly the last sentence in the story. All is closely related, no word is written that has not its specific use in the makeup of my work. I proceed as one might to solve some abstruse problem, by clearly defined lines and deliberately planned steps.”

Though still Anna Katharine Green to the world, she is Mrs. Rohlfs to her friends. She resides in Buffalo, N.Y. in a charming home, made delightful by an appreciative husband and two fair children, Rosamond and Sterling. In appearance she is striking rather than beautiful, but the glory of her hair is a womanly crown. Unbound, it sweeps just to the floor when she stands erect.

Mrs. Rohlfs is a patient and careful writer, spending much time in elaborating her first ideas. Some chapters of “The Leavenworth Case” were rewritten as many as twelve times. “The literary career is a very demanding one,” she wrote two years ago. “If I succeed, it will be by dint of pure work. From morning to night, week in and week out, labor, labor, labor.”

Later words are these:

“I should not advise people to enter upon a literary life who were not driven to it by all the forces of their being. You have to fight, not one day, but a lifetime, to keep abreast of the crowd. Only a special talent, or a certain knack of putting old things in a new light, will insure one immunity from the conflict.”

Her theory in regard to novel writing is this: to have a story to tell, and then to tell it with force and directness, bringing to bear upon every part of it the most absorbing interest.

The exponents of her success have been unusually varied in this country and Europe. Her novels have been dramatized and translated into other languages, her songs have been set to music, but no success stirs her individuality from its equipoise of good judgment and strong common sense. She is bright, kind, and true, and has scores of friends.

Pick Up a Copy of A Deed of Dreadful Note!

Pick Up a Copy of A Deed of Dreadful Note!A Deed of Dreadful Note, first in the Anna Katharine Green Mysteries, is the first and only historical fiction ever written featuring the Mother of Detective Fiction!

Fifteen years before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, Anna Katharine Green began writing The Leavenworth Case, inspiring the creation of detectives like Sherlock, Poirot, and Wimsey, as well as almost every device and convention we now recognize as standard in detective mystery fiction.

When her father’s client is found murdered, Anna takes up the call to prove innocent the young girl accused of the murder. The investigation inspires many of the events, characters, and descriptions that would later be published in her debut novel.

A love letter to mystery and writing itself, A Deed of Dreadful Note is an homage and reintroduction to an author who was the Agatha Christie of her time but a forgotten female today.

This book is a fictionalized account of how Anna Katharine Green’s first novel may have come to be…

NOW AVAILABLE!

Ebook—Amazon (other formats will be available in 3 months)

Audiobook—Wherever audiobooks are sold! Support local and order through Libro.fm!

Print—Order a signed copy from me here! Support local and ask your favorite independent bookstore to order in a copy!

Be sure to request the book through your local library, as well!

Interested in having me speak about Anna Katharine Green?If you haven’t noticed already, I love to talk about AKG!

Please email me at author(at)patricia-meredith.com, or DM me on Instagram or Facebook to check my availability near and far! I am available for both in-person or virtual engagements.

—Learn more about Anna Katharine Green—Watch my YouTube Channel playlist all about Anna Katharine Green.

Head here for a complete timeline of Anna Katharine Green and the History of Mystery Fiction.

AKG and I have a lot in common, it turns out! Watch my video and read this post to learn why I consider Anna Katharine Green my sister from another century.

November 11th is Anna Katharine Green’s birthday! Read this post to learn more about her impact on mystery fiction.

Find my full review, great quotes, and learn how Anna Katharine Green inspired Agatha Christie here from when I re-read The Clocks, and began to really research who this Green woman was.

Read my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read The Leavenworth Case.

Find my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read That Affair Next Door, the first Miss Butterworth case.

—Follow Me Here—Sign up for my newsletter to be the first to hear all the details! You’ll also receive The Leavenworth Case, complete with my special introduction, for FREE for signing up! (Audiobook read by Andrew D. Meredith coming soon!)

Be sure to also follow me on Instagram and Facebook to hear the latest news concerning new book releases and events. And of course, subscribe to my YouTube channel!

You can also add my books to your Want to Read list on Goodreads! Follow my Author Page while you’re there so you’ll be notified when this new book is updated! You can add A Deed of Dreadful Noteto your Want to Read list here!

The post Mary Hatch and Anna Katharine Green appeared first on Patricia Meredith, Author.

June 1, 2023

Quotes Incorporated into A Deed of Dreadful Note

A Deed of Dreadful Note is a piece of historical fiction, created by blending The Leavenworth Case with Anna’s personal history, recorded thoughts, and relationships since, as she said herself, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” Where possible, I have used Anna’s own words to capture the grace and wit with which she approached the world and her writing, in particular.

I’ve now collected all of the quotes incorporated into the novel in one easy-to-access place. You’ll want to bookmark this for your Book Club gathering later!

Quotes Used in A Deed of Dreadful Note Chapter Epigraphs

Chapter Epigraphs“A deed of dreadful note.” —Shakespeare, Macbeth (quoted as an epigraph before the opening chapter of The Leavenworth Case by Anna Katharine Green)

“I have found that the incidents in books which people pick out as improbable are the very ones which are founded on fact. Truth is stranger than fiction.” —Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

“I never write a single story unless I am in the mood for it. I can not. I have to feel and live the parts.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “Life’s Facts as Startling as Fiction,” by Ruth Snyder“For, as you know, dead men tell no tales.” —Gryce, The Leavenworth Case, 1878“…a confusion too genuine to be dissembled and too transparent to be misunderstood.”—The Leavenworth Case“Any attempt at consolation on the part of a stranger must seem at a time like this the most bitter of mockeries; but do try and consider that circumstantial evidence is not always absolute proof.”—The Leavenworth Case“[Anna Katharine Green is] ‘the foremost representative in America today of police-court literature’; yet to us this reference seems unsatisfactory, inadequate. It conveys no hint of the constructive skill, the imaginative power and the perceptive faculties necessary for the praiseworthy writing of police-court literature; and, furthermore, it offers no suggestion of Anna Katharine Green’s exquisite sense of humor.” — E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston, “Anna Katharine Green,” Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901“The hand will often reveal more than the countenance…”—The Leavenworth Case, 1878“At this critical time her father was friend and counsellor.… When doubts arose, when discouragement appeared, he was nearby to cheer her and to advise. He enlisted her sympathy in different cases that interested him; he sharpened her wits ; he discoursed to her on his own interesting experiences; he contributed judicious criticisms; above all, he fostered her confidence in her own powers.” — E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston, “Anna Katharine Green,” Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901“All animated and glowing with his enthusiasm, he eyed the chandelier above him as if it were the embodiment of his own sagacity.”—The Leavenworth Case“I own that I was surprised at the softening which had taken place in her haughty beauty.”—The Leavenworth Case“I even detected Mr. Gryce softening towards the inkstand.”—The Leavenworth Case“My imagination may be stirred by some detail or situation, but until I am thoroughly acquainted with my people, their environment, the thoughts they think, the glances they give, in fact every little element that goes to make up their relationship to the drama in which they are cast, I sit and think, feel and dream, but do not write.”—Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch“I cannot but feel a desire to write him a play in which he may have an opportunity to show himself in a part equally strong but more sympathetic. Whether or not this will eventuate in anything has not yet been communicated to me by the muse.’” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, by T. Fisher Unwin, 1895“The greatest mistake a girl can make is to marry in haste… they do not study his instincts and ideals. They do not know the character of the man they intend to marry.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “Life’s Facts as Startling as Fiction,” by Ruth Snyder“The other night I had a wonderful dream, which has impressed a story on my mind.… It is so passionate, so strong, so subtle, so dread, dark, and heart-rending, it ought to be written with fire and blood.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch“Her father was a well-known lawyer; indeed, the Greens, we have been told, were a family of lawyers. This may account for the skill with which the daughter has tied and cut Gordian knots. It unquestionably accounts for her nimble imagination, her skill in producing subtle hypotheses and her strength in handling the most intricate psychological problems.” —E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston, “Anna Katharine Green,” Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901“Character added to loveliness gives us those rare specimens of womanly perfection which assure us that poetry and art are not solely in the minds of men.” —Anna Katharine Green, “Is Beauty a Blessing?” The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1891“She does not write unless vitally interested in her characters and plot.”— “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895“It will require all my enthusiasm, study and power, and then I may fall short, but I believe I shall sometime try. Perhaps it is somewhat sensational, but I hope by characterization and earnestness to lift it to a higher ground.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch“You expected revelations, whispered hopes, and all manner of sweet confidences; and you see, instead, a cold, bitter woman, who for the first time in your presence feels inclined to be reserved and uncommunicative.”—The Leavenworth Case“It will be observed that she does all that is necessary to cultivate an air of authenticity in what she writes.”—T. Fisher Unwin, Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, 1895“With her, action speaks louder than words.” — “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895“They thought me a good machine and nothing more.”—The Leavenworth Case“I endeavored to put away all further consideration of the affair till I had acquired more facts upon which to base the theory.”—The Leavenworth Case“But, as is very apt to be the case in an affair like this, love and admiration soon got the better of worldly wisdom.”—The Leavenworth Case“All is closely related, no word is written that has not its specific use in the makeup of my work. I proceed as one might to solve some abstruse problem, by clearly defined lines and deliberately planned steps.”—Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch“The chain was complete; the links were fastened; but one link was of a different size and material from the rest; and in this argued a break in the chain.”—The Leavenworth Case“Her circumstances, moreover, though stranger than fiction, are not stranger than truth.” —T. Fisher Unwin, Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, 1895“Her books are read and re-read, and with keener zest upon the subsequent reading than upon the first, when her remarkable constructive skill does not stand in the way of appreciating the many touches indicative of a truly comprehensive and artistic mind.” — “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895“I did not consult my knowledge, sir, in regard to the subject: only my feelings.”—The Leavenworth Case“I declare, now that the thing is worked up, I begin to feel almost sorry we have succeeded so well.”—The Leavenworth Case“A web seemed tangled about my feet.”—The Leavenworth Case“Few authors wait to have a story to tell.” — “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895“Now it is a principle which every detective recognizes, that if of a hundred leading circumstances connected with a crime, ninety-nine of these are acts pointing to the suspected party with unerring certainty, but the hundredth equally important act one which that person could not have performed, the whole fabric of suspicion is destroyed.”—The Leavenworth Case“Her criminals are creatures of circumstance rather than hard-hearted wretches. They have an air of relief at being tracked down—a sure sign of a redeeming flaw in their devilry.” —T. Fisher Unwin, Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, 1895“I will not lose body and soul for nothing.”—The Leavenworth Case“And leaving them there, with the light of growing hope and confidence on their faces, we went out again into the night…”—The Leavenworth Case“‘Have I read The Leavenworth Case? I have read it through at one sitting.… Her powers of invention are so remarkable—she has so much imagination and so much belief (a most important qualification for our art) in what she writes, that I have nothing to report of myself, so far, but most sincere admiration.… Dozens of times in reading the story I have stopped to admire the fertility of invention, the delicate treatment of incidents—and the fine perception of the influence of events on the personages of the story.” —Letter from Wilkie Collins to George Putnam, reprinted in The Critic

“A.K. Green Dies. Noted Author, 88. ‘The Leavenworth Case’ in ’78 Followed by 36 Other Books. Wife of Charles Rohlfs. Wanted to Write Poetry. Wrote Detective Stories to Draw Attention to Her Verse. Changed Mystery Fiction.” —New York Times, April 12, 1935

Poetry by Anna, published in The Defense of the Bride, and Other Poems (1882), written prior to The Leavenworth Case

Through the Trees

Poetry by Anna, published in The Defense of the Bride, and Other Poems (1882), written prior to The Leavenworth Case

Through the Trees

If I had known whose face I’d see

Above the hedge, beside the rose;

If I had known whose voice I’d hear

Make music where the wind-flower blows, —

I had not come; I had not come.

If I had known his deep ‘I love.’

Could make her face so fair to see;

If I had known her shy ‘And!’

Could make him stoop so tenderly, —

I had not come: I had not come.

But what knew I? The summer breeze

Stopped not to cry ‘Beware! beware!’

The vine-wreaths drooping from the trees

Caught not my sleeve with soft ‘Take care!’

And so I came, and so I came.

The roses that his hands have plucked,

Are sweet to me, are death to me;

Between them, as through living flames

I pass, I clutch them, crush them, see!

The bloom for her, the thorn for me.

The brooks leap up with many a song —

I once could sing, like them could sing;

They fall; ’tis like a sigh among

A world of joy and blossoming. —

Why did I come? Why did I come?

The blue sky burns like altar fires —

How sweet her eyes beneath her hair!

The green earth lights its fragrant pyres;

The wild birds rise and flush the air;

God looks and smiles, earth is so fair.

But ah! ‘twixt me and you bright heaven

Two bended heads pass darkling by;

And loud above the bird and brook

I hear a low ‘I love,’ ‘And I—’

And hide my face. Ah God! Why? Why?

PearlsThe wave that floods the trembling shore,

And desolates the strand,

In ebbing leaves, ‘mid froth and wreck,

A shell upon the sand.

So troubles oft o’erwhelm the soul;

And shake the constant mind,

That in retreating leave a pearl

Of memory behind.

At the PianoPlay on! Play on! As softly glides

The low refrain, I seem, I seem

To float, to float on golden tides,

By sunlit isles, where life and dream

Are one, are one; and hope and bliss

Move hand in hand, and thrilling, kiss

‘Neath bowery blooms,

In twilight glooms,

And love is life, and life is love.

Play on! Play on! As higher rise

The lifted strains, I seem, I seem

To mount, to mount through roseate skies,

Through drifted cloud and golden gleam,

To realms, to realms of thought and fire,

Where angels walk and souls aspire,

And sorrow comes but as the night

That brings a star for our delight.

Play on! Play on! The spirit fails,

The star grows dim, the glory pales,

The depths are roused — the depths, and oh!

The heart that wakes, the hopes that glow!

The depths are roused: their billows call

The soul from heights to slip and fall;

To slip and fall and faint and be

Made part of their immensity;

To slip from Heaven; to fall and find

In love the only perfect mind;

To slip and fall and faint and be

Lost, drowned within this melody, —

As life is lost and thought in thee.

Ah, sweet, art thou the star, the star

That draws my soul afar, afar?

Thy voice the silvery tide on which

I float to islands rare and rich?

Thy love the ocean, deep and strong,

In which my hopes and being long

To sink and faint and fail away?

I cannot know. I cannot say.

But play, play on.

ShadowsA zephyr stirs the maple trees,

And straightway o’er the grass

The shadows of their branches shift;

Shift, Love, but do not pass.

So, though with time a change may come

Within my steadfast heart,

The shadow of thy form may stir,

But can not, Love, depart.

Quotes from The Leavenworth Case, 1878, incorporated into A Deed of Dreadful Note (not including the times I point out what she’s written in The Leavenworth Case)Gryce: “Eagerness is not a fault; only the betrayal of it.”Gryce: “It is not enough to look for evidence where you expect to find it. You must sometimes search for it where you don’t.”[paraphrased]

Quotes from The Leavenworth Case, 1878, incorporated into A Deed of Dreadful Note (not including the times I point out what she’s written in The Leavenworth Case)Gryce: “Eagerness is not a fault; only the betrayal of it.”Gryce: “It is not enough to look for evidence where you expect to find it. You must sometimes search for it where you don’t.”[paraphrased] “There are seven chambers here, and they are all loaded.”

A murmur of disappointment followed this assertion.

“But,” he quietly said after a momentary examination of the face of the cylinder, “they have not all been loaded long. A bullet has been recently shot from one of these chambers.”

“How do you know?” cried one of the jury.

“How do I know? Sir,” he said, turning to the coroner, “will you be so kind enough to examine the condition of this pistol?” And he handed it over to that gentleman. “Look first at the barrel; it is clean and bright, you will say, and shows no evidence of a bullet having passed out of it very lately; that is because it has been cleaned. But now, observe the face of the cylinder: what do you see there?”

“I see a faint line of smut near one of the chambers.”

“Just so; show it to the gentlemen.”

It was immediately handed down.

“That faint line of smut, on the edge of one of the chambers, is the telltale, sirs. A bullet passing out always leaves smut behind. The man who fired this remembered the fact, cleaned the barrel, but forgot the cylinder.”

Gryce: “Everyone and nobody. It is not for me to suspect, but to detect.”Quote from Macbeth used as epigraph in Leavenworth Case: “And often-times, to win us to our harm, the instruments of darkness tell us truths, win us with honest trifles, to betray us in deepest consequenceQuote from Macbeth used as epigraph in Leavenworth Case: “A deed of dreadful note.”Quote from Macbeth used as epigraph in Leavenworth Case: “When our actions do not, our fears do make us traitors.” Gryce: “A servant maid who has a grievance is a very valuable assistant to a detective.”Gryce: “I have had a communication from London in regard to the matter. I’ve a friend there in my own line of business, who sometimes assists me with a bit of information, when requested. It is enough for me to telegraph him the name of a person, for him to understand that I want to know everything he can gather in a reasonable length of time about that person.” “And you sent the name of Mr. Quinn to him?” “Yes, in cipher.”Gryce: “Oh, you know I have no opinion. I gave up everything of that kind when I put the affair into your hands.”Gryce: “May I ask, whether you expect to work entirely by yourself; or whether, if a suitable coadjutor were provided, you would disdain his assistance and slight his advice?”Gryce: “Not but that a word from you now and then would be welcome. I am not an egotist. I am open to suggestions: as, for instance, now, if you could conveniently inform me of all you have yourself seen and heard in regard to this matter, I should be most happy to listen.”“He has given me a possible clue——” “Wait,” said Mr. Gryce; “does he know this? Was it done intentionally and with sinister motive, or unconsciously and in plain good faith?” “In good faith, I should say.” Mr. Gryce remained silent for a moment. “It is very unfortunate you cannot explain yourself a little more definitely,” he said at last. “I am almost afraid to trust you to make investigations, as you call them, on your own hook. You are not used to the business, and will lose time, to say nothing of running upon false scents, and using up your strength on unprofitable details.”Gryce: “In other words, you are to play the hound, and I the mole; just so, I know what belongs to a gentleman.”Gryce: “he was engaged in holding a close and confidential confab with his fingertips, and did not appear to notice”Harwell description: “The man lacked any distinctive quality of face or form agreeable or otherwise—being what one might call in appearance a negative sort of person, his pale, regular features, dark, well-smoothed hair and simple whiskers, all belonging to a recognized type and very commonplace. Indeed, there was nothing remarkable about the man, any more than there is about a thousand others you meet every day on Broadway.”“Taking a piece of paper, she jotted down the leading causes of suspicion against Eleanore as follows”Gryce: “Did you ever know a woman who cleaned a pistol? No. They can fire them, and do; but after firing them, they do not clean them.”“A flush of lovely color burst upon us. Blue curtains, blue carpets, blue walls. It was like a glimpse of heavenly azure in a spot where only darkness and gloom were to be expected. Fascinated by the sight, I stepped impetuously forward, but instantly paused again, overcome and impressed by the exquisite picture I saw before me.”“I am very much astonished,” Mr. Gryce went on, winking at me in a slow, diabolical way which in another mood would have aroused my fiercest anger.“Judging from common experience, we had every reason to fear that an immediate stop would be put to all proceedings on our part, as soon as the coroner was introduced upon the scene. But happily for us and the interest at stake, Dr. Fink, of R ——, proved to be a very sensible man. He had only to hear a true story of the affair to recognize at once its importance and the necessity of the most cautious action in the matter. Further, by a sort of sympathy with Mr. Gryce, all the more remarkable that he had never seen him before, he expressed himself as willing to enter into our plans, offering not only to allow us the temporary use of such papers as we desired, but even undertaking to conduct the necessary formalities of calling a jury and instituting an inquest in such a way as to give us time for the investigations we proposed to make.”Turning my attention, therefore, in the direction of Mr. Gryce, I found that person busily engaged in counting his own fingers with a troubled expression upon his countenance, which may or may not have been the result of that arduous employment. But, at my approach, satisfied perhaps that he possessed no more than the requisite number, he dropped his hands and greeted me with a faint smile which was, considering all things, too suggestive to be pleasant.“That is a very pleasing belief,” he observed. “I honor you for entertaining it, Mr. Raymond.”[paraphrased]“(You) have a niece whom you ——— one too who seems worthy the love and trust of any other man ca—— so beautiful, so charming is she in face, form, and conversation. But every rose has its thorn and (this) rose is no exception. Lovely as she is, charming (as she is,) tender as she is, she is capable of trampling on one who trusted her heart to him to whom she owes a debt of honor a ——ance.