Simon Rowe's Blog, page 2

October 21, 2018

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Raising Heaven, Hurts Like Hell

The sound of rolling thunder in the Good Hood can be sourced to the backyard of my Jichikaicho, the neighbourhood Boss. Here, in all its lacquered, braided, tasselled glory, stands our portable shrine, called an omikoshi. Within its main housing, the pièce de résistance - our taiko drum.

The sound of rolling thunder in the Good Hood can be sourced to the backyard of my Jichikaicho, the neighbourhood Boss. Here, in all its lacquered, braided, tasselled glory, stands our portable shrine, called an omikoshi. Within its main housing, the pièce de résistance - our taiko drum.Generating this thunder are the small fists of the neighbourhood school kids. Two weeks before the festival, they hammer volleys into the night sky, honing their skills, perfecting their rhythm for the big day.

One day before the festival, Boss summons me. An extra pair of hands is needed to finish dressing the omikoshi; an intricate and fiddly job which entails bolting, knot-tying, attaching and binding to the shrine all of its trinkets and ornaments. Every small job ends with the passing around of six-packs of Asahi Super Dry. Then quiet slurping and furtive glances towards the sky ensue; everyone wondering if the Gods of Wind (Fūjin (風神) and Thunder (Raijin (雷神) will stay away tomorrow?

Across the archipelago, autumn festivals are held to honour the Shinto gods and give thanks for the rice harvest. But as my good friend Ono-san laments, it’s a spiritual meaning too often drowned in drinking, over-feasting, machismo and all the excitement of carrying the omikoshi.

The night before the festival, our illuminated omikoshi sets sail into streets swarming with school kids and pushed and pulled by fathers who’ve managed to escape work early. Lanterns hang from residents’ porches, guiding the way, as the omikoshi passes like a noisy cruise boat along the darkened streets.

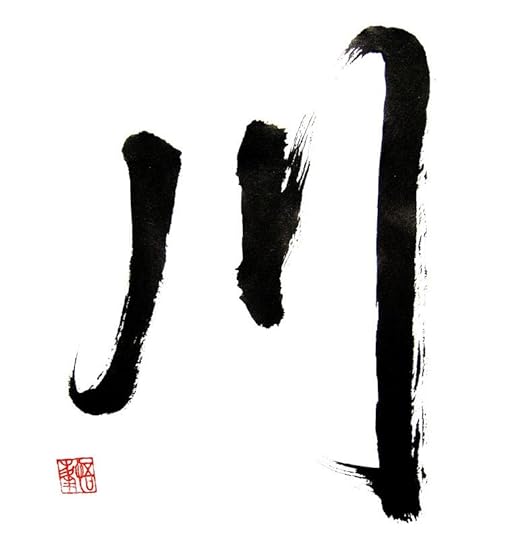

Festival day breaks with a clear crisp dawn. I don my blue hapi jacket with its big red “festival” kanji emblazoned on the back, shake the night’s grit from my head and secure my self-pity with a red bandanna.

The Boss gives a speech. Cups of sake move hand to hand. Squid jerky, too. A staccato drum beat sends the men to the yokes and together we carry the omikoshi to the local shrine to be blessed by the Shinto priest. Joining us are other neighbourhoods with their omikoshi topped with dancing lions and bamboo fronds, each supported by an entourage of mothers, wives, kids, babies in prams, and occasionally, a lost tourist.

The day wears on, the sun beats down, bento and beer flow, and through the Good Hood the omikoshi rumbles and rattles, an old war horse goaded on by an army of kids and a semi-drunken chant from the menfolk. The sound of its drum brings residents to their doors bearing envelopes of gift money. For this, they receive a boisterous, louder semi-drunken chant and vigorous shaking of the shrine by us, the bearers. Rice millers, tatami weavers, barbers, cake shop staff and restaurant waiters come out of their shops to cheer us on. To a destination I’m no longer sure of, or even care. The omikoshi becomes a lifeboat for those who have drunk too much. Stay with us! Don’t let go! The taiko beat feels like a huge rolling rock pounding the inside of our heads.

By late afternoon the chanting eases, the fall of the drumstick dependent more on gravity than human effort; the bearers are tired, the drummers slightly deafened and the mothers’ auxiliary strung out somewhere in the streets behind us. Only the babies waking from their afternoon nap are fist-punching the air.

On sunset, as the crows fly north to roost on the Ichi River, we thank each other for another great day, dismantle and pack up the omikoshi and pull down the roller door on another year. I turn and head for home, bone-weary and beat. The Boss summons me. I cringe, then turn slowly to face my fate: the other annual tradition in the Good Hood I forgot to tell you about--the matsuri AFTER PARTY!

Published on October 21, 2018 03:19

May 30, 2018

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Stormy with a chance of tofu

Rainy season over Himeji, Japan. Simon Rowe 2018 Met my old friend Ono-san in the local yorozuya (‘shop of ten thousand things’) the other day. We had both stepped in from a downpour without seeing each other and met over the tofu tub.

Rainy season over Himeji, Japan. Simon Rowe 2018 Met my old friend Ono-san in the local yorozuya (‘shop of ten thousand things’) the other day. We had both stepped in from a downpour without seeing each other and met over the tofu tub.“Wet season’s here,” she said, fishing out a brick of bean curd. “Good for the hydrangeas.”

“Good for the slugs."

"You got problems?"

"My bathroom’s a mold palace, the rice paper doors have more ripples than a Seto low tide and my tatami mats are so fat, the slugs think they’re water beds.”

“You’ve got a way with words.”

“If I could sell some I wouldn’t eat tofu everyday.”

The ancient cashier flick-flacked her abacus beads, devised a sum — how the hell does she do that? Out in the street, rain drops big enough to fill a sake cup smashed on the bald heads of old men too slow or forgetful to have brought an umbrella.

Wet season, or tsuyu, has arrived. From now until early July it will wrap the Good Hood in a hot, damp fug; some days a steamy downpour, sometimes days a long, warm drizzle whose moisture and dimness will conspire to turn my old townhouse into a Welcome Inn for terrestrial gastropods.

Some light reading in preparation for this onslaught: “Like most gastropods, a slug moves by rhythmic waves of muscular contraction on the underside of its foot. It simultaneously secretes a layer of mucus that it travels on, which helps prevent damage to the foot tissues.” (Denny, M. W.; Gosline, J. M. (1980). "The physical properties of the pedal mucus of the terrestrial slug, Ariolimax columbianus"). At first, I thought these were instructions on how to Moonwalk. Then I remembered — zoologists don’t dance.

Ono-san’s hydrangeas will burst into giant volleyballs of pastel hues and nod their big dripping heads. Neighbors will admire them. My slugs will loll about growing wise and fat on mold and tasty titbits dropped by my kids.

Can’t blame the kids so I blame the gods: the collision of two giant weather systems — warm, moist air pushing up from the Philippines smashing into the last of the cold northerlies drifting down from Siberia — gives us what the Japan Meteorological Agency calls with professional dourness: a “relatively stable bad weather front over Japan which lasts several weeks.”

Tsuyu sounds nicer. It means “plum rain,” with no hint of slime, and though I have no idea why the fruity innuendo, I guess it has something to do with the size of the raindrops. In the dead of night a cloudburst can sound like ten million pickled plums being machine-gunned onto the roofs of the Good Hood. On nights of such drama, I curl up beneath my bed sheet, happy to know that between me and nature’s wrath lie roof tiles made by men who knew how to make a roof tile.

Alas, 100-year-old houses don’t chill well. They were built to ‘breathe’ with clay-mud walls and paper doors that absorbed, filtered and circulated air, light and moisture. Modern household clutter nullifies this effect; it turns a large, breezy house into an Amazon riverboat full of empty wine bottles with a cabin fever that turns sane men into serial killers.

Yet the people of the Good Hood, and of greater Himeji city, endure. They have done for centuries. They sling bamboo shades from their windows, hang wind chimes from their eaves, flap uchiwa and sensu hand fans against their streaming faces and flock to the rooftop beer gardens downtown, hopeful for a salty breeze off the Seto Inland Sea.

“There are people who complain about the wet season,” says Ono-san. “But look at the positives. The city is cleansed, the cedar pollen and Gobi sand flushed away. AND it’s good for the..."

“Hydrangeas.”

I don’t think I’ve ever met a woman so adept at turning black into white.

Days later we were inundated. The Good Hood turned riverine in minutes. My courtyard flooded, the runoff by-passed the roof guttering and overflowed the storm water drains. The Semba River became a superhighway for lost volleyballs, Coke bottles, milk cartons, baseballs and beer cans, all of them racing towards the Seto Inland Sea. Snakes, frogs and turtle evacuated the river en masse and the great herons and crows feasted on them. One crow whip-snapped a paddy snake three times its length, the turtles fared better.

I took the train west to Ako the next day. The rain had flooded the rice paddies making the land look like one huge broken mirror, reflecting the blue sky and towering white thunderheads. Farm hamlets clutch the fringes of these mirror fields, nestled beneath green mountains as lumpy as a crocodile's back. Green. Lumpy.

I reminded myself to stop by the yorozuya and pick up a sack of salt for my new house guests.

Published on May 30, 2018 19:43

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Warm and moist, but no fruitcake.

Rainy season over Himeji, Japan. Simon Rowe 2018 Met my old friend Ono-san in the local yorozuya (‘shop of ten thousand things’) the other day. We had both stepped in from a downpour without seeing each other and met over the tofu tub.

Rainy season over Himeji, Japan. Simon Rowe 2018 Met my old friend Ono-san in the local yorozuya (‘shop of ten thousand things’) the other day. We had both stepped in from a downpour without seeing each other and met over the tofu tub. “Wet season’s here,” she said, fishing out a brick of bean curd. “Good for the hydrangeas.”

“Good for the slugs."

"You got ナメクジ problems?"

"My bathroom’s a mold palace, the rice paper doors have more ripples than a Seto low tide and my tatami mats are so fat with moisture, the slugs think they’re water beds.”

“You’ve got a way with words.”

“If could sell some I wouldn’t eat tofu everyday.”

The ancient cashier flick-flacked her abacus beads, devised a sum — how the hell does she do that? Out in the street, rain drops big enough to fill a sake cup smashed on the bald heads of old men too slow or forgetful to have brought an umbrella.

Wet season, or tsuyu, has arrived. From now until early July it will wrap the Good Hood in a hot, damp fug; some days a steamy downpour, sometimes days a long, warm drizzle whose moisture and dimness will conspire to turn my old townhouse into a Welcome Inn for terrestrial gastropods.

Some light reading in preparation for this onslaught: “Like most gastropods, a slug moves by rhythmic waves of muscular contraction on the underside of its foot. It simultaneously secretes a layer of mucus that it travels on, which helps prevent damage to the foot tissues.” (Denny, M. W.; Gosline, J. M. (1980). "The physical properties of the pedal mucus of the terrestrial slug, Ariolimax columbianus"). At first, I thought these were instructions on how to Moonwalk. Then I remembered — zoologists don’t dance.

Ono-san’s hydrangeas will burst into giant volleyballs of pastel hues and nod their big dripping heads. Neighbors will admire them. My slugs will loll about growing wise and fat on mold and tasty titbits dropped by my kids.

Can’t blame the kids so I blame the gods: the collision of two giant weather systems -- warm, moist air pushing up from the Philippines smashing into the last of the cold northerlies drifting down from Siberia — gives us what the Japan Meteorological Agency calls with professional dourness: a “relatively stable bad weather front over Japan which lasts several weeks.”

Tsuyu sounds nicer. It means “plum rain,” with no hint of slime, and though I have no idea why the fruity innuendo, I guess it has something to do with the size of the raindrops. In the dead of night a cloudburst can sound like ten million pickled plums being machine-gunned onto the roofs of the Good Hood. On nights of such drama, I curl up beneath my bed sheet, happy to know that between me and nature’s wrath lie roof tiles made by men who knew how to make a roof tile.

Alas, 100-year-old houses don’t chill well. They were built to ‘breathe’ with clay-mud walls and paper doors that absorbed, filtered and circulated air, light and moisture. Modern household clutter nullifies this effect; it turns a large, breezy house into an Amazon riverboat full of empty wine bottles with a cabin fever that turns sane men into serial killers.

Yet the people of the Good Hood, and of greater Himeji city, endure. They have done for centuries. They sling bamboo shades from their windows, hang wind chimes from their eaves, flap uchiwa and sensu hand fans against their streaming faces and flock to the rooftop beer gardens downtown, hopeful for a salty breeze off the Seto Inland Sea.

“There are people who complain about the wet season,” says Ono-san. “But look at the positives. The city is cleansed, the cedar pollen and Gobi sand flushed away. AND it’s good for the..."

“Hydrangeas.”

I don’t think I’ve ever met a woman so adept at turning black into white.

Days later we were inundated. The Good Hood turned riverine in minutes. My courtyard flooded, the runoff by-passed the roof guttering overflowing the storm water drains overflowed. The Semba River became a superhighway for lost volleyballs, Coke bottles, milk cartons, baseballs and beer cans, all of them racing towards the Seto Inland Sea. Snakes, frogs and turtle evacuated the river en masse and the great herons and crows feasted on them. One crow whip-snapped a paddy snake three times its length, the turtles fared better.

I took the train west to Ako the next day. The rain had flooded the rice paddies making the land look like one huge broken mirror, reflecting the blue sky and towering white thunderheads. Farm hamlets clutch the fringes of these mirror fields, nestled beneath green mountains as lumpy as a crocodile's back. Green. Lumpy.

I reminded myself to stop by the yorozuya and pick up a sack of salt for my house guests.

Published on May 30, 2018 19:43

May 10, 2018

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Night and the City

‘The problem with the world is that everyone is a few drinks behind.’

~ Humphrey Bogart

The problem with Friday nights in the Good Hood is that everyone is a few drinks ahead. Which is not to say I’m a slow drinker—I’ll raise my glass to your health as fast as the next drunk—it’s just that by the time I've finished work, helped with the chores and read "Harry the Dirty Dog" or "Where The Wild Bums Are" to the little people of my household, Hana-kin is almost gone.

Hana-kin means ‘Flower Friday.’ Seasoned drinkers who survived the dancefloors and big hair of Japan’s 80s Bubble era still use the term to describe the day when a week’s worth of paper shuffling, screen-staring, drifting through meetings and endless trips to the green tea dispenser come to an end, and night and city beckon.

To Japanese youth, the term Hana-kin is archaic—like grandad’s shoestring neckties or Tahitian Lime hair tonic—and likely conjures up images of drunken businessmen singing karaoke with neck-tie bandanas while their junior female colleagues pour drinks and mop up the vomit of those who have passed out. It is true—I have borne witness. And yes, the youngbloods are right: Hana-kin does need an image upgrade.

The gap between old and young doesn’t bother me; I feel equally at ease in the raucous dive bars on Himeji's Salt Town (塩町) Street and the faux wine bars of Fish Town (魚町) Street. But in the end, there’s no place like home, and my home for the past twenty years has been the Good Hood north of Himeji Castle, an old neighborhood which survived the WWII fire bombings and still brims with community spirit. I like to drink with ‘my people.’ That’s why on Friday nights, whenever I can, I make for a place where the salt-of-the-earth gathers like a crust on the counter.

To the Poodle Bar!

The Poodle sits at the confluence of a busy street and the deathly quiet one which leads into my neighborhood. Before the roller door goes up around 6p.m., the counter has been wiped, ashtrays set at half-metre intervals, toilet scrubbed and the karaoke volume adjusted downwards from the previous night. Around 7p.m., the first customers drift in, the early birds, the oldtimers, pensioners, widowers, maybe a retired mobster or two. Later, their seats will be taken by factory workers, truck drivers, lonely single men and the odd housewife on-the-run.

Come on in, take a seat and start your night with the words, ‘Tori-aizu, biru!’ (A coldie for starters!). There’s nothing like a glass of brown bubbles to slacken the jaw and loosen tongue. But tonight, as on most Fridays, the seasoned drinkers are ahead. For the pensioner, the two grease monkeys with calloused knuckles, the huddle of smoking housewives and the jokester singing ‘Top of the World’, that first beer is a distant memory.

Bottles of Black Mist Island Shōchū (焼酎) line the counter, the ‘bottle keeps’ of these regular patrons, each bearing the name of the man or woman in front of it. This is serious drinking, Mum; the kind that makes an Irish funeral wake look like a child’s tea party.

Tonight promises to be a king tide at the Poodle Bar. Tonight all boats will be lifted, some may lose their rudders, others will flounder and sink, and the lucky ones will limp home to port and a dry dock for the rest of the weekend. The unlucky with be bundled into a taxi and driven to an address of their best pronunciation.

The Poodle Mama oversees this night-time circus with the ease of a woman who sees it every Friday night. She is a woman in her late 50s who looks like what Raymond Chandler might have called a ‘drawn-out dame.’ Her makeup is thick, I cannot tell if she is smiling or grimacing as she moves between patrons, pouring beers, working swizzle sticks, encouraging the money flow across the counter. Will she sing a song? Will she? The pensioner pleads. His cajoling ends in a sad (very sad) ballad about love lost in snowy Hokkaido.

The Poodle Mama is clapped off vigorously by the young mechanics at the end of the bar and a greasy microphone is thrust into my hand—with a song pre-selected. And so once again, the deathly quiet street which leads to my home resounds with the words, ‘On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair, warm smell of colitas rising up through the air…’

Admittedly, closing time at Poodle is an hour I seldom see; the messiness, mayhem and mumbling missing persons reach me only as sounds lost in the night, when I am safely tucked up in my futon and dreaming of water skiing bikini girls and a warm tide lapping at my toes.

Which reminds me...

If I ever open a bar here, I will call it the High Tide Bar and I will raise a neon sign over the counter which will read in atomic orange kanji, ‘If you drink to forget, please pay in advance.'

Published on May 10, 2018 17:08

February 12, 2018

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Birth of a Salesman

Shibuya crossing - a paperback salesman's view. Simon Rowe 2017

Shibuya crossing - a paperback salesman's view. Simon Rowe 2017 So comfortable has life in an old Japanese neighborhood become that after twenty years it is now the single greatest threat to my sense of adventure.

Truth be told, the Good Hood will ruin a man; make him give up shopping to exist on gifts of onions, egg plants and sweet potato from the local gardeners, weaken his resolve to spend money on a meal downtown because the delicious aromas of close-quarters cooking remind him that dining local is where soul food really is. Or make him just stay in, because the sound of the neighbors’ TV game shows, screaming tots and husband-vs-wife arguments gives him that cozy, safe feeling of humanity pressing in on all sides.

No need even to wander far for entertainment in the Good Hood. At the Poodle Bar, three alleys up, you can drink for one coin and sing "Take It Easy" for a sitting ovation.

And yet I feel the slow creep of the uchi-muki phenomenon, the ‘inward-looking’ mindset, which the media says is sucking Japanese youth of their adventurous spirit.

So I did something about it. I found a clean collar, some sensible shoes, packed some copies of my self-published book, and bought a ticket to the Capital—the Big Soosh—city of insomniacs, home of the neon tan and the suited, chain-smoking millions who sing “Under Pressure” on Mondays and scream “Let me out!” on Fridays.

All trains lead to the Capital. In the olden days, feudal lords from across the archipelago left their fiefs to make the mandatory pilgrimage to meet with the Shogun in Edo (Tokyo) each year. From Himeji, it would have been a three-day butt-buster in an express palanquin. Now you can do it in three hours aboard a N700-series Nozomi express with salted peanuts and a six pack of Kirin road soda.

Granted, the heaving concourses of Tokyo’s Shinagawa Station are just as fast. An old canoeing mate of mine once said: “Always paddle faster than the current, dude”. Scott, if you are reading this, nothing paddles faster than the current in Shinagawa Station because the current is electrified, the drum of footsteps louder than any downpour on the Glenelg River and the smell of humanity, well, let’s just say it’s better than yours after a week on the river. But I digress...

Exit 27C is where I came up for air. Fortunately, I wasn’t in Shingawa anymore. I was in Shinjuku, and like a feudal lord (hauling his own baggage) I headed straight for the palace door. Kinokuniya Shinjuku is the royalty of bookstores in Japan; eleven floors of literature, a million books in the offing, and I was cold-calling on the most powerful person an indie writer could request an audience with—the Merchandising Manager.

Back in the Good Hood, door-to-door salespersons are as common as cat fights on garbage night; you can get anything from rice cakes to roast sweet potatoes, term deposits to the teachings of Jehovah, so I didn’t think twice about fronting up to the counter unannounced. But the Merchandising Manager was amazed. ‘You came all the way to Tokyo to deliver a sample of your book personally?’ he said incredulously. ‘Like a lord,’ I replied (though I think my quip went unappreciated).

A self-published author has approximately sixty seconds to deliver his spiel; there’s no time for nervous sweats or tongue-tied sales pitches, the Manager is a busy person. He watched, he listened, he felt the texture of the book’s pages, ran his pianist’s fingers down the spine, the barcode, the ISBN...then he spoke: ‘Look around you, almost all of our stock comes through a few American and British distributors. It simplifies out paperwork…’

I looked around at the big fish—the literary prize winners, represented authors—which swam gracefully by to the cash registers. Yes, I was a minnow in a salmon race. A minnow on a mission. With naught to lose and everything to gain. So I offered free shipping. The Manager listened. I offered to pay for return delivery of unsold books. The Manager smiled.

For the rest of that afternoon, I felt like a cork on a storm water drain; a cork with a paddle, and I did paddle faster than the current, through the neon canyons of Shinjuku to Shibuya and on to Ginza where the buying managers of other big bookstores greeted me and listened and took my samples with smiling faces and nods of appreciation. The experience became the adventure; the near empty suitcase, my sense of achievement.

And with achievement, comes rewards.

Under the Yamanote Line train track that night, I met with an old friend. We entered a tunnel and bowled out the other side into an alleyway filled with bobbing red lanterns and smoking braziers where salesfolk just like myself sat happily wedged into impossibly narrow eateries, laughing and drinking, and beckoning us to join them. And so the night passed, in drunken bonhomie with Tokyo’s hardest working, far from the Good Hood and its Poodle Bar, its husband-and wife warfare and cat fights on garbage night, until that feeling of all-good-things-must-end was suddenly thrust into my hand—the bill.

Now, I’ve always believed that a person’s story is their currency in this life, so to the manager with the grubby bandanna and sweat-stained chef’s jacket, I proposed a deal: food for fiction—the very last copy of my book, Good Night Papa: Short Stories from Japan and Elsewhere in exchange for the wings and the beer.

He didn’t buy it.

Published on February 12, 2018 23:39

June 29, 2017

Notes from Himeji, Japan: The Semba unplugged

Last night I had a dream I was trapped inside a castle besieged by peasants. They were carrying pitchforks and chanting, ‘Down with the King, down with the King!’. Since I live in a house with a kitchen sink view of a 500-year-old samurai castle, this was a completely plausible dream scenario. Only it wasn’t a dream. A rowdy mob really was below my window and it was chanting, ‘River clean! River clean!’ (Kawa-soji! Kawa-soji!).

Across Japan whole communities are picking up their buckets, rakes, scythes, barrows and pitchforks, to clear their neighborhood rivers of debris and weed before the first rains of the wet season arrive in late June.

With so much clamoring there was nothing for it but to leap from my futon, slip on my best threadbare rags, and join the march towards our mighty Semba River, the waterway which wends through the Good Hood, past the samurai castle, the bars, clubs and love hotels of FishTown before sidling under the bullet train tracks and emptying into the Seto Inland Sea.

Under the direction of the Jichi-kai-cho (Hood boss) I took up my position at the floodgates. This is where the most interesting debris accumulates; not the usual flotsam like beer cans, baseballs, slippers and soccer balls—that’s for the downriver people. I mean the heavy junk. Junk with stories, like adult movie collections (owner got a girlfriend), air guns (owner’s girlfriend threw it out), electric fans (owner’s girlfriend demanded air-con) and bicycles (owner bought a motor-scooter to escape girlfriend). Regardless of who put it there, and in what state of sanity, sobriety or slovenliness they might have been at the time, all this stuff must be fished out before the wet season deluge arrives.

River north, river south, all along the Semba’s banks, folk from our neighboring neighborhoods were hard at work, scything, dredging, shovelling, hauling weed and whatnot to big stinking riverside heaps. Wheelbarrows formed queues, manned by elderly women with big forearms and sensible shoes; a man sauntered by with a cigarette hanging off his lip, a pink bucket filled with brown muck in his hand and a twinkle in his eye that said 8am is never too early for a beer. He emptied his bucket and disappeared, leaving the two teetotallers to tend the muck heap.

It’s not only the river that needs cleaning—the sluiceways also. These narrow drains which connect the rice paddies are important because they funnel away overflow after typhoons. They also provide easy escape routes for the garbage corner tomcats, ferrets and other pets-on-the-run, and in summer, hours of entertainment for kids who catch medaka (tiny fish) for their home aquariums and ‘science experiments’..

This year my job was to lean precariously over the deepest part of the river, where the rapid churns in a vertical motion, and use a garden rake to dislodge all the heavy crap that gets stuck. There were no airguns or adult movie collections this year, just a mountain of pongy-smelling weed which soaked me through and left me scented like river itself.

Which is not to say that the our Semba is dirty. In fact, a sign of a healthy river is the presence of fireflies and this year there were many. Nights in the Good Hood were filled with the shouts and squeals of kids chasing them along the river bank from late May to mid-June. Which meant that there was a certain sadness in the river cleaning, because when you cut away the grass, you’re kicking out the fireflies. Smokin Joe Matsumoto, the old kitchen gardener who lives up my street, chimed in with his two yen on the matter. He said, ‘There used to be so many fireflies here, that when we swatted them with our hand fans it was like a shower of sparks.’ I wasn’t sure if this comment was meant to cheer me up or not.

Nevertheless, the technical high school on the other side of the river has developed a Healthy River program which encourages students to breed fireflies in the school’s artesian well water system. Then, at the end of May, they are released at a nighttime open-invitation event for all the surrounding neighborhoods to enjoy.

Unplugged, the Semba now runs freely. Like everything in the Good Hood, it doesn’t get done without teamwork. And though, at times, it sometimes seems futile (the river weed and junk will be back with the summer), community spirit is always stronger for it. We all now await, eyes skyward, the rainy season.

http://www.mightytales.net/

Published on June 29, 2017 20:45

June 22, 2017

Notes from Himeji, Japan: The Colour of the Night

The Ghost House entrance curtain, Himeji Yukata Matsuri. Simon Rowe.

The Ghost House entrance curtain, Himeji Yukata Matsuri. Simon Rowe. A long time ago (250 years thereabouts), a powerful dude named Sakakibara Masamune decreed that the people of his castle town slip into something more comfortable and shimmy downtown for a good time. “Do what?” his attendants asked. “Throw a party, you monkeys! I’m outta here!”

Indeed he was, off to rule another fiefdom, but not before starting a tradition that would fill the fine streets of Himeji with colourful summer kimono (ゆかた, yukata), octopus dumplings and (a little later) skyrockets and riot police for three days a year, every year thereafter.

More than just a celebration of the highly functional yukata, it’s a fashion show. Women’s yukata colours are brighter, patterns livelier, and shock! horror! hems are rising. The elderly women of the Good Hood shake their heads and click their tongues at these parading young things in mini yukata; the young fellas just nod their heads and knock themselves out with their tongues.

The Yukata Festival, held June 22-24 every year, also celebrates the rainy season. That’s right, it is the WETTEST time of the year (news just in: no rain forecast for June 22-24th) which doesn’t stop several hundred thousand people from choking the streets and alleys south of Himeji castle with coin to spend on cold beer, toys and tasty treats. There were once more than 800 stalls, erected and manned by a small army of itinerant carnivaleers called tekiya. The big hand of City Hall has nearly halved this number in recent years, in order to manage the heavy crowds. The effect, as always, has been like squeezing a tube of toothpaste - same crowds, smaller space.

Word on the street is that the tekiya are in cohorts with the local yakuza; others say that’s an unfair image and that the stall holders are just abiding by a ‘system’ which takes a nice slice of their earnings and hands it to the mob. Let’s call it a ‘licensing fee’. The City seems OK with this as it ‘stimulates’ the local economy and frees up their rubber stamps for more pressing matters. Times have changed since I tagged along with some English teachers to my first Yukata Festival 20 years ago. Then, youth gangs flocked from all over the province to wage theatrical (and sometimes violent) running pitched battles with their rivals on the city streets. Hard to believe in peace-loving Japan? Well listen to this: watching riot police get pelted with skyrockets, drag troublemakers off to paddy wagons by their orange hair, and see the odd motor scooter get barbecued, reminded me of the Costa Rican fruit vendor riots of ‘91 (Yes, I was in Costa Rica in 1991). Cheap entertainment for the masses, poor public relations for the police, not exactly a festive family affair.

That’s all gone. The police have changed their tune. They now use subterfuge and infiltration tactics, clever stuff like putting dozens of plain clothes officers into the crowds to catch troublemakers on digital camera or video. Maybe this has worked, or maybe the young punks have just gotten older, gotten married and gotten a job, because the Yukata Matsuri IS now a family affair.

‘Smokin Joe’ Matsumoto, the old kitchen gardener who lives on my street in the Good Hood, will be taking his grandchildren again this year. Those long sleeves of his faded yukata will be sure to hold a pack of cigarettes, a lighter and some coins for cotton candy. My old friend Ono-san won’t be going; she thinks it’s too crowded, too noisy, the food tasteless and too expensive. “I’m saving my yukata for the fireworks festivals,” she says.

If YOU go, be sure to drop by the Ghost House at the edge of Otemae park; it has been a going concern for years, adept at taking your money and scaring the beejeezuss out of you with the screams of other teenage patrons. They say a good ghosting chills you out during a long, hot Japanese summer. Personally I’d prefer a cold beer...

Published on June 22, 2017 17:14

April 7, 2017

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Life on the Razor’s Edge

The legendary Toshiro Mifune grooming himself before stepping onto the set Sometimes good things can be found in the most unlikely places. For the best shave in my city, I go to the hospital. The Himeji Junkanki Centre Hospital, to be exact. This mysterious facility hides in the hills south of the train tracks and is only known to people with heart conditions, poor blood circulation or a poor sense of direction.

The legendary Toshiro Mifune grooming himself before stepping onto the set Sometimes good things can be found in the most unlikely places. For the best shave in my city, I go to the hospital. The Himeji Junkanki Centre Hospital, to be exact. This mysterious facility hides in the hills south of the train tracks and is only known to people with heart conditions, poor blood circulation or a poor sense of direction.Down a hallway, in a warren of hallways, past its blood drawing room, stomach camera room, X-Ray closet, a cafe of philosophical waitresses and a kiosk which sells everything for double-and-a-half, at the very end, stands a small barber shop. The sign over the door should say ‘Style with a smile’ or ‘Life is short, but our buzzcut is shorter’. Instead it just says “Barber”.

On a busy day the wheelchairs are backed up around the corner. Waiting time is short, however, on account of the mostly elderly patrons who don’t have much hair to speak of. It's not the cut they come for anyway; it’s the ‘old school’ shave. I haven’t been around long enough to know what ‘old school’ means, but to recline in a classic Takara-Belmont barber chair with the tang of Tahitian Lime hair tonic in your nostrils and feel the liquid smoothness of an Iwasaki straight razor rolling across your chin and cheeks, is to savor one of the great intimate pleasures of Japan.

A shave at the Junkanki Centre Hospital Barbershop is also my chance to step out of a lightspeed lifestyle for fifteen minutes, to drift off into a hot-lathered land where the hustle of a hospital sounds like a far-off cocktail party through which white-uniformed stewardesses push trolleys of clinking martinis and...be brought back to earth by the jolt and jerk of the chair, a brisk shampoo and a scalp rub which leaves me wondering where I am, what time it is and...

There are two staff; an elderly man with a voice that sounds like a food processor full of thumb tacks and a middle-aged woman with a voice that doesn't. They share the glass shelves of scalp tonic, tubs of baby powder and hair wax, double-edged razors, clippers, a steam oven filled with hot towels, and a transistor which radio plays Okinawan ballads in the morning and baseball in the afternoon.

For some reason it’s the woman who always cuts my hair and shaves me. She tells me she has two young sons and two jobs. I know she works hard and her shoulder massages make me remember it. I’ve often wondered if her second job is dough rolling in a noodle joint, or maybe she has a black belt in shiatsu? I will ask her next time. We talk about our kids mostly, our neighborhoods, the seasonal festivals and the different viruses currently circulating at the kids’ schools. She knows my local liquor store owner (he’s also her customer) which means our seiken (world) really is semai (small), which is really the essence of Japanese community spirit. It’s this reassurance and safety 'by association' that gets you through doors and gets you good service, which of course is a two-way street. I always tip ten percent.

Almost all the old neighborhoods in Himeji have a barbershop. They are considered an ‘essential local service’, and seemed to have outlasted the rice millers, tatami mat weavers, coffee shop owners, butchers and fishmongers. The barber shop also remains a kind of ‘bush telegraph’ where (mostly) men go to chew the fat and shoot the breeze, and some not to get a haircut at all.

On my street in the Good Hood stands the Funabiki Barber Shop with its red and blue spiralling pole and cheerful snip-snipping sounds emanating from the tiled floor inside. It’s run by a family of barbers who rise with the sun and are still hard at it after dark. In Autumn, their kids practice taiko drumming with mine, and send them to me with bag fulls of fresh wakame seaweed and strings of onions. Once, I went for a haircut with a hangover. I fell asleep in the chair and awoke with a shaven forehead, ears and nostrils smooth, and a coiffure like a professional Japanese baseball player.

There is only one other place I have ventured into in Himeji. It’s called Royal, and I won’t be going back. Royal is what’s known as the ‘shearing sheds’ in the Australian vernacular. It’s Sweeney Todd without the head-rolling and meat pies. A long line of chairs face a continuous mirror and manning these are men who might have once been pet groomers, tree doctors or failed ramen chefs. Golf is a popular sport in Japan, although to play eighteen holes can be cost prohibitive. But if you really want eighteen holes, it will only cost ten bucks at Royal.

Published on April 07, 2017 20:21

March 11, 2017

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Greenhouse Blues

The Haru-Ichiban (春一番, First Wind of Spring) is afoot. It’s at this time of year, when my nose runs like snowmelt and my eyes itch with hay fever, that my finger hovers over the 'book now' button for a low-cost carrier going anywhere between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, any place where cedar pollen and Gobi sand, which the last of the Siberian northerlies bring to western Honshu, have no local translation.

Problem, as always, is funds. You can’t get on the big silver bird without a big silver coin. So, there will be no Bintang in Bali, Sling in Singapore or Singha in Siam, to celebrate winter’s end this year, boo-hoo.

About a month ago, however, something fortuitous happened. I discovered a large greenhouse beside the mountain where I work. It is used by the Faculty of Pharmacological Science to grow medicinal plants for research and is tended by a retinue of elderly men in powder blue overalls who water and weed and keep the insects in check.

The good thing about March is that there are no university classes; the researchers are all off in Borneo or Guatemala, or wherever it is that they go to study medicinal plants, give medicinal presentations and try local 'medicine' (for medicinal purposes only), which leaves myself and the powder-blue people to enjoy this pollen-free paradise in peace.

When I first stepped inside the greenhouse, it was mid January. Outside was a big fat zero; inside, the lush 25 degrees had me loosening my collar and humming “April Sun in Cuba” while I settled down to read my lunchtime paperback. It was Charles Bukowski’s Post Office, a winding yarn about a guy (himself) who skives off during working hours to go gamble on horses, drink, chase women and write bestsellers.

Now, the powder blue people disappear around lunchtime, so after a few weeks I started to feel a little lonely sitting in this jungle all by myself. To remedy the problem I sent out an invitation to my long-time friend, the old kitchen gardener who lives up my street, Smokin Joe Matsumoto, asking him to join me.

I thought he might enjoy sitting around and telling yarns about ‘old Japan’ beneath the Piper longum (peppercorn) bush, Tamarindus indica (tamarind) tree, Cymbopogon (lemongrass), Zingiber officinale (ginger), jasmine and orchids, but I’m yet to hear back from him.

I’d like to show him the Rauvolfia serpentina (Indian snakeroot) which, I've since found out, contains 200 known alkaloids and is used as a traditional antivenin to treat snake bites in India. A little more reading and I discovered that Alexander the Great used it to cure Ptolemy of a poisoned arrow injury; Mahatma Gandhi also took it as a sedative (for stress? yeah, right). Snakeroot contains reserpine, an antipsychotic, antihypertensive alkaloid, which was once used by Western medicine to treat high blood pressure and schizophrenia. It is still one of the 50 most used plants in Chinese medicine.

I will knock on Smokin Joe’s door again. He has a bear-like tendency to venture out in late March when the fragrance of the plum and cherry blossoms carries on the Haru-Ichiban.

On second thoughts, I fear our little ‘green-ins’ will attract attention. If other administration staff find out they can take their coffee breaks in the tropics, it might get a little too hot in there. I must be careful.

The other day I finished the Charles Bukowski book and searched my shelves for the next thing to take to the greenhouse; I passed over Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (too dark), Spencer Chapman’s WWII soldiering-in-Malaya memoir The Jungle Is Neutral (too long), and Peter Matthiessen’s missionaries-in-the-Amazon adventure At Play in the Fields of the Lord (too much drama). In the end, I picked out an old favourite, Eric Hansen’s Stranger in the Forest, about his journey on foot from one side of Borneo to the other.

So with coffee and book in hand, and whistling Guns ‘n Roses’ “Welcome to the Jungle”, I returned to the greenhouse yesterday.

Only to find it locked.

Published on March 11, 2017 16:15

February 7, 2017

Notes from Himeji, Japan: Journeys of the Imagination

What do “You Only Live Twice” (1967), “The Last Samurai” (2003) and “Good Night Papa” (2016) have in common? All use the Japanese city of Himeji as their location.

This city of half a million festival-crazed people lies 35 kilometres west of Kobe and is famed for its 500-year-old samurai castle, Himeji-jo. It is also where ‘Papa’ Matsumoto, retired taxi driver and central character of Good Night Papa lives. Where, on a warm June night and the eve of his daughter’s death three years earlier, he is forced by a mysterious passenger in kimono to review his life's misfortunes—and receives an unexpected gift in return.

This story is first in a line-up of fifteen short tales set in Japan, Australia, Fiji, China, Morocco, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Spain and Mexico. They are tales teased from hours of sitting, writing, drinking, thinking and watching people during fifteen years of travelling as a freelance writer. The ‘research’ amounts to a leaning tower of curry-stained, coffee-ringed notebooks filled with scribblings on sights, sounds, smells and brushes with the ugly, beautiful and unfamiliar, all of which have helped this writer to create authentic settings and (hopefully) ‘believable’ characters.

A central theme of the GNP story collection is ‘triumph over adversity’. In tales like “The Pilgrim”, “Baby Grand” and “The Foonabiki Barbers”, the characters use wit and fast-thinking to deal with their dilemmas and conundrums. Others use irony to reveal the (dark) humour of their actions.

The paradox, of course, is that fiction is rooted in fact. Some real life occurrences cannot be imagined, like the stories of the Japanese soldiers, Teruo Nakamura (actually Taiwanese), Shoichi Yokoi and Hiro Onoda, who held out on jungled islands for years, not knowing that WWII had ended. “Bones” draws inspiration from their stories. Others like, “The Girl Who Made The Kung Fu Master Cry” (which involved ten days of intense calisthenics at a Shaolin kung fu school to research) and “Weed” (a bone-jarring three-hour boat ride with octopus fishermen on the Sea of Cortez in Mexico) seek to show how perseverance triumphs over hardship.

My own days ‘on the road’ are almost done. Most of the travelling is inside my head now, since writing fiction allows me to fly anywhere for the price of a coffee. The tales in Good Night Papa: Short Stories from Japan and Elsewhere are therefore journeys of my imagination which I hope will linger in the minds of the reader—for the price of this book and a coffee!

Print copies are available at www.mightytales.net and Amazon.com.

This city of half a million festival-crazed people lies 35 kilometres west of Kobe and is famed for its 500-year-old samurai castle, Himeji-jo. It is also where ‘Papa’ Matsumoto, retired taxi driver and central character of Good Night Papa lives. Where, on a warm June night and the eve of his daughter’s death three years earlier, he is forced by a mysterious passenger in kimono to review his life's misfortunes—and receives an unexpected gift in return.

This story is first in a line-up of fifteen short tales set in Japan, Australia, Fiji, China, Morocco, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Spain and Mexico. They are tales teased from hours of sitting, writing, drinking, thinking and watching people during fifteen years of travelling as a freelance writer. The ‘research’ amounts to a leaning tower of curry-stained, coffee-ringed notebooks filled with scribblings on sights, sounds, smells and brushes with the ugly, beautiful and unfamiliar, all of which have helped this writer to create authentic settings and (hopefully) ‘believable’ characters.

A central theme of the GNP story collection is ‘triumph over adversity’. In tales like “The Pilgrim”, “Baby Grand” and “The Foonabiki Barbers”, the characters use wit and fast-thinking to deal with their dilemmas and conundrums. Others use irony to reveal the (dark) humour of their actions.

The paradox, of course, is that fiction is rooted in fact. Some real life occurrences cannot be imagined, like the stories of the Japanese soldiers, Teruo Nakamura (actually Taiwanese), Shoichi Yokoi and Hiro Onoda, who held out on jungled islands for years, not knowing that WWII had ended. “Bones” draws inspiration from their stories. Others like, “The Girl Who Made The Kung Fu Master Cry” (which involved ten days of intense calisthenics at a Shaolin kung fu school to research) and “Weed” (a bone-jarring three-hour boat ride with octopus fishermen on the Sea of Cortez in Mexico) seek to show how perseverance triumphs over hardship.

My own days ‘on the road’ are almost done. Most of the travelling is inside my head now, since writing fiction allows me to fly anywhere for the price of a coffee. The tales in Good Night Papa: Short Stories from Japan and Elsewhere are therefore journeys of my imagination which I hope will linger in the minds of the reader—for the price of this book and a coffee!

Print copies are available at www.mightytales.net and Amazon.com.

Published on February 07, 2017 17:11