Kevin Patrick's Blog, page 2

June 26, 2019

World's Greatest Crime Smasher!

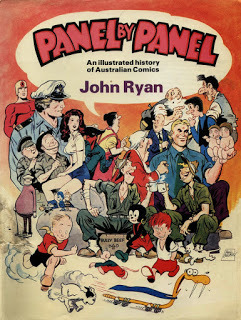

For many Australian comic-book fans growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, John Ryan's landmark book, Panel By Panel (1979), provided us with our first tantalizing glimpse of Australian comic books and their creators from the 1940s to the 1960s. These were, in my case, at least, the comic books of my father's childhood and early adolescence, and were testimony to the creative and commercial vibrancy of Australia's post-war comic book industry (You can read Ryan's "Introduction" to Panel by Panel, along with a brief article by Ryan on the history of Australian comics, at Nat Karmichael's Comicoz website). Ryan's book seized my imagination, and fueled my lifelong interest in the history of Australian comic books, which, as it turned out, would undergo a modest renaissance throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. I was fortunate enough to have Ryan's book as an essential springboard for my burgeoning research into "vintage" Australian comics from the 1940s-'60s, while seeing the so-called "New Wave" of Australian comics unfurl before me, as I began writing for local comic fanzines and amateur press associations (APAs) throughout the 1980s.

For many Australian comic-book fans growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, John Ryan's landmark book, Panel By Panel (1979), provided us with our first tantalizing glimpse of Australian comic books and their creators from the 1940s to the 1960s. These were, in my case, at least, the comic books of my father's childhood and early adolescence, and were testimony to the creative and commercial vibrancy of Australia's post-war comic book industry (You can read Ryan's "Introduction" to Panel by Panel, along with a brief article by Ryan on the history of Australian comics, at Nat Karmichael's Comicoz website). Ryan's book seized my imagination, and fueled my lifelong interest in the history of Australian comic books, which, as it turned out, would undergo a modest renaissance throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. I was fortunate enough to have Ryan's book as an essential springboard for my burgeoning research into "vintage" Australian comics from the 1940s-'60s, while seeing the so-called "New Wave" of Australian comics unfurl before me, as I began writing for local comic fanzines and amateur press associations (APAs) throughout the 1980s.Panel by Panel was lavishly illustrated with black & white reproductions of interior pages from both famous and obscure comic magazines from the postar era. But for many younger readers like myself, the real highlight was the dozen-or-so-pages of full-colour reproductions of classic comic book covers While Ryan's accompanying text provided some details about many of the featured titles, these colour covers set me on a lifelong quest to seek out prized examples of these amazing comics. In those decades prior to the advent of the internet, tracking down such rare (and presumably valuable) comics seemed an almost impossible task (The launch of eBay Australia in 1999 was a godsend for comic collectors and researchers alike - when I wasn't emptying my wallet online, I could at least download and save images of rare Australian comics that went up for auction in ever-growing numbers, and sold at record-breaking prices, throughout the 2000s).

Yet many of the comics featured in that colour gallery from Panel By Panel would elude my grasp for decades thereafter. One in particular really caught my eye - it was the cover for the first issue of The Shadow, drawn by Peter Chapman for Frew Publications in the early 1950s. The cover held me spellbound then, and I still consider it to be one of the most dynamic, and compelling designs ever to grace an Australian comic book. The mysterious figure of The Shadow, his face concealed by a latex mask, looms godlike over the dramatic scene unfolding in the skies below his gaze. A sleek jet fighter pursues a flying saucer, while a leggy brunette, held aloft by a parachute, drifts slowly to the Earth's surface. This was, the cover proclaimed, a new series featuring the "World's Greatest Crime Smasher!" But to me, it was a near-perfect encapsulation of the 1950s Cold War "zeitgeist" - but who was The Shadow? What happened to that woman? And who - or what - was at the controls of the UFO? I thought I'd never learn the answer to these questions...until now!

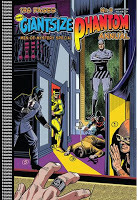

The latest issue of Giantsize Phantom Annual (No.9), published by Frew Publications - Australia's oldest surviving comic book publisher - is a "Men-of-Mystery Special". Australian cartoonists, it seemed, were far more comfortable - and successful - when it came to creating "masked vigilantes", rather than American-styled superheroes. This special edition of Giantsize Phantom Annual features some of the best "men-of-mystery" comics from that era, including "The Grey Domino" (Terry Trowell), "The Raven" (Paul Wheelahan), and "The Mask" (Yaroslav Horak). And nestled in among these great stories is my very own comic-book equivalent of the "Maltese Falcon" - the first issue of The Shadow.

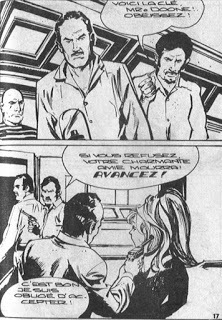

And what an utterly dotty and delightful comic it is! Jimmy Gray, a wealthy, indolent playboy, is courting beautiful young Gloria Palmer, daughter of a famed, but reclusive scientist. Gray goes to visit Gloria, but is astonished to see a flying saucer rocket into the sky from the grounds of her father's home. Gray abandons his carfree, gadfly persona when he dons his distinctive skin-tight rubber mask, and instead enters the Palmer residence as The Shadow, nemesis of crime. He swiftly learns that Professor Palmer's daughter has been kidnapped by the Black Rajah, who until now had been bankrolling Palmer's flying saucer project. But upon learning that his benefactor plans to use these flying machines to achieve world domination, Professor Palmer refused to build any further UFOs for this crazed despot. The Black Rajah kidnapped Gloria, and whisked her away to his remote Indian hideout aboard one her father's flying saucers, threatening to kill her unless her father resumed work on his hi-tech flying machines.

The Shadow leaps into action, and flies headlong to the Black Rajah's mountain fortress aboard his own supersonic fighter jet, which is swiftly intercepted by a fleet of three flying saucers. Upon landing, The Shadow swiftly overpowers the Black Rajah's guards, and rescues Gloria Palmer from the Black Rajah's lascivious clutches. He takes the Black Rajah hostage, and forces him at gunpoint to lead all three of them to the private landing strip where Professor Palmer's flying saucers are stored. The Shadow ushers them aboard one of the UFOs, and takes the strange vessel skyward - but not before he uses its fearsome death ray to destroy both his own captured jet fighter, and the two remaining flying saucers, to prevent them from falling into "the wrong hands".

The strange trio streak across the skies towards England, but when the flying saucer starts to lose fuel, The Shadow persuades Gloria to strap on a parachute and bail out of the stricken vessel before it crashes. He then orders the Black Rajah to "hit the silk", but warns him not to attempt to flee England, as he will radio their position to Scotland Yard, and will be apprehended by detectives the moment he lands. The Black Rajah, who acknowledges The Shadow's courage, jumps without protest. The Shadow manages to land the flying saucer safely, and hurriedly makes his way to the Palmer household, where Gloria is tearfully reunited with her father. The Shadow makes his entrance as Jimmy Palmer, but is given the cold-shoulder from Gloria, who secretly wishes that Jimmy Gray were a real man, like The Shadow.

Ah, if only she know, eh? I hope this breathless summary adequately conveys the breakneck pace, and sheer implausibility of The Shadow's high-altitude escapades. Logic and realism take a backseat as The Shadow surmounts one obstacle after another in his pursuit of Gloria Palmer and the Black Rajah - but not before he rids the world of Professor Palmer's deadly inventions. The Shadow does not compare favorably with other "mystery men" comics featured in this issue of Giantsize Phantom Annual, which boast superior storylines and illustrations. But it has an undeniable charm, which suggest that, whatever its shortcomings, The Shadow resonated with Australian audiences, for whom comics were no more than an entertaining diversion, offering a brief, fantastic escape from the dull routines of everyday life. Selling for just eightpence a copy back in the 1950s, I'd say that readers of The Shadow got a fair return on their investment. (Images courtesy of 20th Century Danny Boy, AusReprints, Comicoz, and Frew Publications)

Ah, if only she know, eh? I hope this breathless summary adequately conveys the breakneck pace, and sheer implausibility of The Shadow's high-altitude escapades. Logic and realism take a backseat as The Shadow surmounts one obstacle after another in his pursuit of Gloria Palmer and the Black Rajah - but not before he rids the world of Professor Palmer's deadly inventions. The Shadow does not compare favorably with other "mystery men" comics featured in this issue of Giantsize Phantom Annual, which boast superior storylines and illustrations. But it has an undeniable charm, which suggest that, whatever its shortcomings, The Shadow resonated with Australian audiences, for whom comics were no more than an entertaining diversion, offering a brief, fantastic escape from the dull routines of everyday life. Selling for just eightpence a copy back in the 1950s, I'd say that readers of The Shadow got a fair return on their investment. (Images courtesy of 20th Century Danny Boy, AusReprints, Comicoz, and Frew Publications)

Published on June 26, 2019 18:47

May 5, 2019

Ledger of Honour 2019 - Gerald Carr

The Ledger Awards were launched in 2005 to acknowledge excellence in Australian comic art and publishing. Named in honour of the expatriate Australian artist, Peter Ledger, the awards went into extended hiatus after 2007, but were subsequently relaunched in a new format in 2014. The Ledger Awards are not only an annual celebration of the best new Australian comics and graphic novels, but its special "Ledger of Honour" category acknowledges the historical contributions that great Australian cartoonists - both living and dead - have made to Australian comic books in decades past (Disclaimer: I have served as a member of the Ledger of Honour judging panel in 2016, 2017 and 2019).

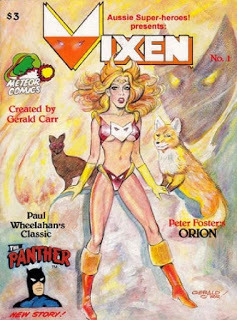

The Ledger Awards were launched in 2005 to acknowledge excellence in Australian comic art and publishing. Named in honour of the expatriate Australian artist, Peter Ledger, the awards went into extended hiatus after 2007, but were subsequently relaunched in a new format in 2014. The Ledger Awards are not only an annual celebration of the best new Australian comics and graphic novels, but its special "Ledger of Honour" category acknowledges the historical contributions that great Australian cartoonists - both living and dead - have made to Australian comic books in decades past (Disclaimer: I have served as a member of the Ledger of Honour judging panel in 2016, 2017 and 2019). I'm delighted to share the news that Gerald Carr was awarded the "Living Legend" for the 2019 Ledger of Honour award, in recognition of his outstanding contribution to Australian comics. Carr has enjoyed an wide and varied career dating back to the late 1960s, when he was a preeminent comic strip artist for the popular music magazine,

Go-Set

, and the satirical current affairs newspaper,

Broadside

. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, he was an enterprising comic book writer, illustrator and publisher, releasing such comic magazines as Vampire, Brainmaster & Vixen, Shock Raider and Fire Fang, spanning the horror, science-fiction and superhero genres and geared towards an older adult readership, at a time when Australian comics were deemed all but extinct.

I'm delighted to share the news that Gerald Carr was awarded the "Living Legend" for the 2019 Ledger of Honour award, in recognition of his outstanding contribution to Australian comics. Carr has enjoyed an wide and varied career dating back to the late 1960s, when he was a preeminent comic strip artist for the popular music magazine,

Go-Set

, and the satirical current affairs newspaper,

Broadside

. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, he was an enterprising comic book writer, illustrator and publisher, releasing such comic magazines as Vampire, Brainmaster & Vixen, Shock Raider and Fire Fang, spanning the horror, science-fiction and superhero genres and geared towards an older adult readership, at a time when Australian comics were deemed all but extinct.I've written about Gerald Carr elsewhere on this blog, and I would encourage Australian comic fans to visit Gerald's own website, Vixen, dedicated to his curvaceous superheroine, which contains numerous samples of his published work, and you can also follow Gerald Carr on Twitter, where he shares his latest news and artwork.

Congratulations once again to Gerald Carr for receiving the "Living Legend"/Ledger of Honour for this year's Ledger Awards.

Published on May 05, 2019 19:43

December 31, 2018

Paul Wheelahan, Storyteller (1930-2018)

Paul Wheelahan, early 2000sI've written about Paul Wheelahan on numerous occasions over the last two decades, but having learned that he passed away on 28 December 2018, I think it's a sad, but fitting, occasion to mark my (long overdue) return to the

Comics Down Under

blog with this tribute to his singular career as a comic-book writer/illustrator, and as a prolific author of "pulp fiction" Western novels. I'll always remember Paul as a lively, gregarious bloke, forever willing to share anecdotes and insights from his eventful life and career, and as a man who remained passionate about his craft towards the very end of his life. I hope this blog entry does sufficient justice to one of Australia's greatest unsung storytellers.

Paul Wheelahan, early 2000sI've written about Paul Wheelahan on numerous occasions over the last two decades, but having learned that he passed away on 28 December 2018, I think it's a sad, but fitting, occasion to mark my (long overdue) return to the

Comics Down Under

blog with this tribute to his singular career as a comic-book writer/illustrator, and as a prolific author of "pulp fiction" Western novels. I'll always remember Paul as a lively, gregarious bloke, forever willing to share anecdotes and insights from his eventful life and career, and as a man who remained passionate about his craft towards the very end of his life. I hope this blog entry does sufficient justice to one of Australia's greatest unsung storytellers.Paul Wheelahan was born on 6 November 1930, and grew up in Dalton, a country town in New South Wales, where his father was stationed as a mounted policeman. Blessed with a keen imagination, Paul exhibited an aptitude for art from a young age, and immersed himself in the escapist fantasies of Depression-era Hollywood films (especially those starring Australian-born actor Errol Flynn), as well as newspaper "funnies" and early Australian tabloid comics, such as Wags . His adolescent ambition to become a comic-book artist - a career choice greeted with dismay by his parents - was driven in part by Silver Starr in the Flameworld, a majestic science-fiction comic strip illustrated by Stanley Pitt (1925-2002), which appeared in Sydney's Sunday Sun and Guardian newspaper in November 1946. Paul went to Sydney and sought out Pitt, who invited him to visit his studio, where Paul eventually worked as an art assistant on Yarmak - Jungle King Comic, which Pitt began producing for Young's Merchandising Co. in 1948. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship, one that would have enormous influence on Paul's future career as a writer.

Paul Wheelahan cover art, circa 1955Paul obtained freelance assignments from Sydney publisher H.J. Edwards, who commissioned him to provide cover illustrations for the company's locally licensed reprints of American comics (See Blazing West, No.2, at right). Paul's debut comic-book story - a science-fiction adventure titled "The Adventures of Space Hawk" - appeared as a back-up feature in Rangers Comics No. 3 (circa 1951), and was the first of several self-contained comic-book stories that Paul wrote and illustrated for H.J. Edwards' growing range of Western, war and crime comic magazines throughout the early 1950s.

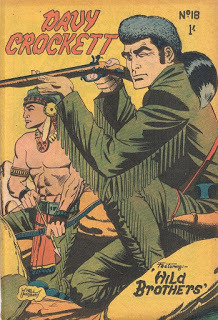

Paul Wheelahan cover art, circa 1955Paul obtained freelance assignments from Sydney publisher H.J. Edwards, who commissioned him to provide cover illustrations for the company's locally licensed reprints of American comics (See Blazing West, No.2, at right). Paul's debut comic-book story - a science-fiction adventure titled "The Adventures of Space Hawk" - appeared as a back-up feature in Rangers Comics No. 3 (circa 1951), and was the first of several self-contained comic-book stories that Paul wrote and illustrated for H.J. Edwards' growing range of Western, war and crime comic magazines throughout the early 1950s.But Paul became disillusioned with the struggle to secure regular, let alone lucrative, employment as a comic-book writer and illustrator, and briefly returned to his parents' home in rural New South Wales, where he found employment as a tree-cutter and demolition worker on the Oaky River Dam project. By chance, he read a magazine article about the popularity of Walt Disney's Davy Crockett television series starring Fess Parker, which sparked an enormous craze for Davy Crockett-themed merchandise. Wheelahan took his idea for developing an all-new Davy Crockett comic to Charles Young (director of Young's Merchandising), arguing that it would it capitalize on the series' anticipated popularity in Australia, where it was eventually screened as a cinematic release for local audiences. Paul's hunch proved correct, and his first-ever solo comic book series, Davy Crockett - Frontier Scout , was a runaway success for Young's Merchandising Co.

Davy Crockett No.18, circa 1957.

Davy Crockett No.18, circa 1957.Paul dusted off a character he'd first developed for some sketch studies in the late 1940s as the basis for his next project for Charles Young. The Panther, a mysterious figure raised in the wilds of the Belgian Congo, made his debut in 1957, and proved an immediate hit with readers. The Panther was an amalgam of Lee's Falk's comic-strip hero, The Phantom, and Edgar Rice Burroughs' famous novel, Tarzan of the Apes, who fought wild beasts, treacherous poachers and warring tribes with unmatched ferocity. It wasn't long, however, before Paul sent his hero on exotic adventures around the world, pitting him against the Nazi war criminal Quintinella (and his evil henchman, Zuni), as well as battling modern-day pirates, Cold War spies, gangsters, and tyrannical despots (Paul even sent The Panther to the Australian Outback, where he fought Aboriginal tribesmen) Paul developed a bolder, more confident art style with each successive issue, but the series also demonstrated his capacity for crafting imaginative, fast-paced stories and developing memorable, larger-than-life characters.

The Panther No.13, circa 1958The Panther was a rare success among Australian-drawn comic books, which not only had to compete with cheaper local reprints of American comics, but now faced a new commercial threat following the launch of television broadcasting in 1956, which lured away readers in ever-growing numbers by the end of the decade. By 1960, this dire situation was compounded following the removal of import licensing restrictions on American comic magazines - originally imposed at the outbreak of World War II - which now allowed full-colour American comic books to flood the domestic market. Despite this challenging publishing environment, Charles Young encouraged Paul to produce another comic book for his company, no doubt hoping that "lightning would strike thrice", and yield further commercial success for Young's Merchandising.

The Panther No.13, circa 1958The Panther was a rare success among Australian-drawn comic books, which not only had to compete with cheaper local reprints of American comics, but now faced a new commercial threat following the launch of television broadcasting in 1956, which lured away readers in ever-growing numbers by the end of the decade. By 1960, this dire situation was compounded following the removal of import licensing restrictions on American comic magazines - originally imposed at the outbreak of World War II - which now allowed full-colour American comic books to flood the domestic market. Despite this challenging publishing environment, Charles Young encouraged Paul to produce another comic book for his company, no doubt hoping that "lightning would strike thrice", and yield further commercial success for Young's Merchandising. The Raven No.1, circa 1962As it turned out, Paul's third, and final, comic book series -

The Raven

- proved every bit as popular as The Panther. Set in modern-day England, The Raven was, in reality, Lord Ashley, the Seventh Earl of Ravenscourt, wrongly imprisoned for a daring art theft committed by his brother, Sebastian, a small-time criminal. Determined to clear his name, Lord Ashley escapes from prison, and returns to his ancestral home, where he dons the guise of The Raven, a hooded vigilante determined to fight injustice wherever it may be found. Now confronted with the task of writing and illustrating two monthly comic books, Paul employed a different art technique for The Raven, juxtaposing fully-rendered figures against minimal backdrops, a time-saving technique which inadvertently lent the series a stark, dramatic look. Launched in 1962, The Raven generated unprecedented response from readers, their enthusiastic letters confirming that Paul's latest creation was poised to become yet another success for Young's Merchandising Co. But the character's promising future was abruptly curtailed when the company was closed down following the death of publisher Charles Young in 1963.

The Raven No.1, circa 1962As it turned out, Paul's third, and final, comic book series -

The Raven

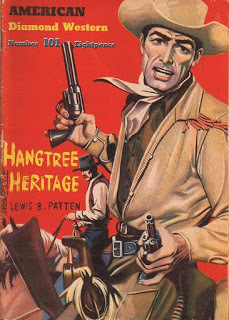

- proved every bit as popular as The Panther. Set in modern-day England, The Raven was, in reality, Lord Ashley, the Seventh Earl of Ravenscourt, wrongly imprisoned for a daring art theft committed by his brother, Sebastian, a small-time criminal. Determined to clear his name, Lord Ashley escapes from prison, and returns to his ancestral home, where he dons the guise of The Raven, a hooded vigilante determined to fight injustice wherever it may be found. Now confronted with the task of writing and illustrating two monthly comic books, Paul employed a different art technique for The Raven, juxtaposing fully-rendered figures against minimal backdrops, a time-saving technique which inadvertently lent the series a stark, dramatic look. Launched in 1962, The Raven generated unprecedented response from readers, their enthusiastic letters confirming that Paul's latest creation was poised to become yet another success for Young's Merchandising Co. But the character's promising future was abruptly curtailed when the company was closed down following the death of publisher Charles Young in 1963. Cover by Stanley Pitt, mid-1950sPaul's friend and mentor, Stan Pitt, intervened once more at this crucial juncture in his life, and helped Paul embark on an entirely new career as a novelist. By the mid-1950s, Pitt had largely abandoned newspaper comic strips and comic magazine work, and had become a sought-after cover artist for many local publishers specialising in cheap, ephemeral "pulp fiction" novelettes and short-story magazines. Pitt produced vivid, eye-catching cover designs for countless romance, crime, science-fiction and Western novels and magazines throughout this period, He eventually became one of the small stable of artists employed by Cleveland Publishing Company, the Sydney-based firm founded by Jack Atkins in 1953, which produced the

Larry Kent/I Hate Crime

novels (based on the popular radio serial of the same name), in addition to an expansive range of Western, crime/detective and war "pulp" titles. Stan told Paul that his years spent writing comic books proved that he was, first and foremost, a storyteller, and encouraged him to submit a manuscript to Cleveland Publishing. Paul sat down at his typewriter, and hammered out his first-ever Western novel, titled Never Ride Back, in 1963. The editors at Cleveland Publishing liked his manuscript, but wanted assurances that Paul had more than one story in him. They needn't have worried - when Never Ride Back was eventually published in 1964 (sporting a cover illustration by Stan Pitt), it was the first of an estimated 800 novels that Paul wrote for the company under the pseudonyms "Emerson Dodge" and "Brett McKinley" (among others) for the next thirty-four years.

Cover by Stanley Pitt, mid-1950sPaul's friend and mentor, Stan Pitt, intervened once more at this crucial juncture in his life, and helped Paul embark on an entirely new career as a novelist. By the mid-1950s, Pitt had largely abandoned newspaper comic strips and comic magazine work, and had become a sought-after cover artist for many local publishers specialising in cheap, ephemeral "pulp fiction" novelettes and short-story magazines. Pitt produced vivid, eye-catching cover designs for countless romance, crime, science-fiction and Western novels and magazines throughout this period, He eventually became one of the small stable of artists employed by Cleveland Publishing Company, the Sydney-based firm founded by Jack Atkins in 1953, which produced the

Larry Kent/I Hate Crime

novels (based on the popular radio serial of the same name), in addition to an expansive range of Western, crime/detective and war "pulp" titles. Stan told Paul that his years spent writing comic books proved that he was, first and foremost, a storyteller, and encouraged him to submit a manuscript to Cleveland Publishing. Paul sat down at his typewriter, and hammered out his first-ever Western novel, titled Never Ride Back, in 1963. The editors at Cleveland Publishing liked his manuscript, but wanted assurances that Paul had more than one story in him. They needn't have worried - when Never Ride Back was eventually published in 1964 (sporting a cover illustration by Stan Pitt), it was the first of an estimated 800 novels that Paul wrote for the company under the pseudonyms "Emerson Dodge" and "Brett McKinley" (among others) for the next thirty-four years. Never Ride Back, 1964Even when abiding by Cleveland Publishing's rather narrow editorial edicts - Native American "Indians" could never be cast as anything other than villains, for example - Paul's tireless imagination wrung every possible variation on the stock characters and scenarios common to the Western genre. At his fastest, Paul said he could begin plotting a new 40,000-word novel on a Monday, and deliver the finished manuscript to Cleveland Publishing by Friday afternoon - just in time to cash his pay cheque, and join his fellow writers at a nearby pub. Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Paul developed new, ongoing paperback series under yet another pseudonym, "E. Jefferson Clay". These included Benedict and Brazos (starring two brawling Civil War veterans), and Savage, an amoral gunslinger whose exploits - peppered with sex and violence - reflected the vogue for grittier Western yarns popularized by so-called "Spaghetti Western" movies of the 1960s and 1970s. One of Paul's more memorable Western novels was Everybody's Gunnin' for Dunn, which starred many of the people who'd worked for Cleveland Publishing as the lead characters, including writer Des Dunn, artist Stan Pitt and publisher Les Atkins (who took over the business from his father in the early 1970s).

Never Ride Back, 1964Even when abiding by Cleveland Publishing's rather narrow editorial edicts - Native American "Indians" could never be cast as anything other than villains, for example - Paul's tireless imagination wrung every possible variation on the stock characters and scenarios common to the Western genre. At his fastest, Paul said he could begin plotting a new 40,000-word novel on a Monday, and deliver the finished manuscript to Cleveland Publishing by Friday afternoon - just in time to cash his pay cheque, and join his fellow writers at a nearby pub. Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Paul developed new, ongoing paperback series under yet another pseudonym, "E. Jefferson Clay". These included Benedict and Brazos (starring two brawling Civil War veterans), and Savage, an amoral gunslinger whose exploits - peppered with sex and violence - reflected the vogue for grittier Western yarns popularized by so-called "Spaghetti Western" movies of the 1960s and 1970s. One of Paul's more memorable Western novels was Everybody's Gunnin' for Dunn, which starred many of the people who'd worked for Cleveland Publishing as the lead characters, including writer Des Dunn, artist Stan Pitt and publisher Les Atkins (who took over the business from his father in the early 1970s).Cleveland Publishing outlasted most of its rivals, many of which had exited the mass-market fiction field by the mid-1960s, as more and more readers turned to television and cinema to satisfy their thirst for Western yarns. As it happened, Paul made a brief foray into local television drama during the 1980s, working as screenwriter for the children's television series, Runaway Island , which was broadcast on the Seven Network, as well as penning several episodes of the popular soap opera, A Country Practice, which, according to Paul, "never saw the light of day". Throughout this period, Cleveland Publishing remained profitable, thanks to its loyal, "rusted on" readership, but as their monthly publishing schedule gradually contracted over successive decades, the company ceased commissioning new manuscripts from its authors in the late 1990s. Paul wrote his last novel for the company in 1996, but this by no means spelled the end of his writing career. Undaunted by the loss of his chief writing outlet, Paul launched his own company, Dodge Publishing, and released three self-published Western novels - Savage Texas, Arizona Psycho, and Sons of Cain - in the late 1990s. This was the first time that his Western novels were published under his own name, instead of the American-sounding pseudonyms that Cleveland Publishing imposed on its Australian authors.

Vixen No.1, 1992Paul's creative legacy in Australian comics was by no means forgotten, making occasional guest appearances at local comic conventions in the 1980s, where he met fans and collectors who'd grown up reading The Panther and The Raven during the heyday of Australia's comic-book industry. In 1992, Melbourne comic creator/publisher Gerald Carr - with Paul's blessing - produced an all-new episode of The Panther, which appeared as a supporting featuring in Carr's superhero comic,

Vixen

. My own personal connection with Paul began around 1999-2000, when I secured permission to reprint the original Panther series in chronological order, and secured newsstand distribution for this all-new edition of The Panther comic throughout Australia and New Zealand - the first Australian-drawn title to achieve such exposure in over a decade, according to our distributor, Gordon & Gotch (Sadly, despite initially positive sales and enthusiastic reader feedback, this latter series was cancelled in 2002 after just five bi-monthly issues).

Vixen No.1, 1992Paul's creative legacy in Australian comics was by no means forgotten, making occasional guest appearances at local comic conventions in the 1980s, where he met fans and collectors who'd grown up reading The Panther and The Raven during the heyday of Australia's comic-book industry. In 1992, Melbourne comic creator/publisher Gerald Carr - with Paul's blessing - produced an all-new episode of The Panther, which appeared as a supporting featuring in Carr's superhero comic,

Vixen

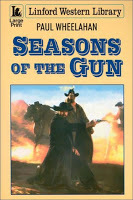

. My own personal connection with Paul began around 1999-2000, when I secured permission to reprint the original Panther series in chronological order, and secured newsstand distribution for this all-new edition of The Panther comic throughout Australia and New Zealand - the first Australian-drawn title to achieve such exposure in over a decade, according to our distributor, Gordon & Gotch (Sadly, despite initially positive sales and enthusiastic reader feedback, this latter series was cancelled in 2002 after just five bi-monthly issues). Seasons of the Gun (US ed), 2002Paul, in the meantime, had already embarked on what would become the final phase of his long and prolific writing career. The new millennium found him producing novels for the British publisher, Robert Hale, which specialized in publishing Western titles under its "Black Horse Western" imprint, intended primarily for the lending library market in Britain, Australia, and the United States. Some of Paul's earliest titles for Hale/Black Horse, such as Branded (2000) and Seasons of the Gun (2001), were published under his own name, but it wasn't long before his prodigious output was appearing under a raft of new pseudonyms, including "Dempsey Clay" (The .45 Goodbye, 2009), "Matt James", (Always the Guns, 2009) and "Ryan Bodie" (Loner with a Gun, 2010).

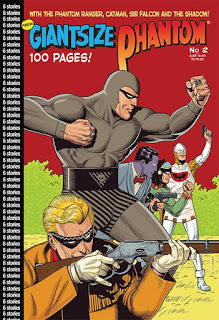

Seasons of the Gun (US ed), 2002Paul, in the meantime, had already embarked on what would become the final phase of his long and prolific writing career. The new millennium found him producing novels for the British publisher, Robert Hale, which specialized in publishing Western titles under its "Black Horse Western" imprint, intended primarily for the lending library market in Britain, Australia, and the United States. Some of Paul's earliest titles for Hale/Black Horse, such as Branded (2000) and Seasons of the Gun (2001), were published under his own name, but it wasn't long before his prodigious output was appearing under a raft of new pseudonyms, including "Dempsey Clay" (The .45 Goodbye, 2009), "Matt James", (Always the Guns, 2009) and "Ryan Bodie" (Loner with a Gun, 2010). Giant Size Phantom Annual No.5, 2018Sadly, Paul was forced to give up his writing career, according to his daughter, Caitlin Wheelahan, after he was diagnosed with early onset dementia around 2010. Nevertheless, Paul's creative legacy was duly acknowledged in 2017 when he received the "Ledger of Honour" award, in recognition of his outstanding contribution to Australian comic art (You can download a PDF version of the 2017 Ledger Awards Annual, which features a retrospective of Paul's career, by clicking this link). Today, a new generation of Australian comic book fans can rediscover Paul's classic heroes, The Panther and The Raven, whose exploits are now being reprinted in the Giant Size Phantom comic (commencing with issue No.5), by Frew Publications. In the end, there can be no more fitting tribute to the life and work of Paul Wheelahan - a truly gifted storyteller who thrived in the egalitarian mediums of comic books and "pulp fiction" literature, and enthralled generations of readers with his vivid imagination.

Giant Size Phantom Annual No.5, 2018Sadly, Paul was forced to give up his writing career, according to his daughter, Caitlin Wheelahan, after he was diagnosed with early onset dementia around 2010. Nevertheless, Paul's creative legacy was duly acknowledged in 2017 when he received the "Ledger of Honour" award, in recognition of his outstanding contribution to Australian comic art (You can download a PDF version of the 2017 Ledger Awards Annual, which features a retrospective of Paul's career, by clicking this link). Today, a new generation of Australian comic book fans can rediscover Paul's classic heroes, The Panther and The Raven, whose exploits are now being reprinted in the Giant Size Phantom comic (commencing with issue No.5), by Frew Publications. In the end, there can be no more fitting tribute to the life and work of Paul Wheelahan - a truly gifted storyteller who thrived in the egalitarian mediums of comic books and "pulp fiction" literature, and enthralled generations of readers with his vivid imagination.(Images courtesy of ABE Books, Amazon.com, AusReprints, Black Horse Extra, Frew Publications, and Gerald Carr's Vixen)

Published on December 31, 2018 16:34

November 28, 2017

Planetary Republic of Comics - New Website

Planetary Republic of Comics is a new website curated by Frederick Luis Aldama, Arts and Humanities Distinguished Professor, (Department of English), Ohio State University. The website currently features dozens of entries about global comics culture, from leading comics studies scholars.

Planetary Republic of Comics is a new website curated by Frederick Luis Aldama, Arts and Humanities Distinguished Professor, (Department of English), Ohio State University. The website currently features dozens of entries about global comics culture, from leading comics studies scholars.Dr Golnar Nabizadeh, Lecturer in Comics Studies at the University of Dundee, and myself were invited to write several entries about key Australian comics and their creators. Hopefully, over time, we - in conjunction with other Australian scholars - will add further entries and resources about Australian comics history to the site.

Visitors can search the site by region and/or country, creators' names, or character and/or series title. Planetary Republic of Comics is a fascinating and informative resource for anyone who wants to learn more about the international history of comics (Image courtesy of ComicVine).

Published on November 28, 2017 20:10

November 15, 2017

The Phantom Ranger - See him in Giant Size Phantom!

I've had an article published in the recent edition of Giant Size Phantom comic (Number 2), released by Frew Publications (Australia).Giant Size Phantom is a showcase-styled magazine, which reprints some of Frew Publications' earlier Australian-drawn comics from the 1940s and 1950s, when Australia's comic-book industry was at its peak of commercial success Australia had a population of just over 9 million people back then, but Australians were reading 60 million comic books annually by 1954. Crikey!My first article for this magazine focuses on The Phantom Ranger, an Australian-drawn cowboy Western comic, which was tremendously popular back in the day.After they'd finished reading the latest issue of The Phantom Ranger comic book, Aussie kids could deck themselves out from head-to-toe in licensed Phantom Ranger clothing, and tune in to The Phantom Ranger radio serial, starring the late Australian actor, Charles "Bud" Tingwell.Australian readers can purchase their copies Giant Size Phantom (Number 2) online, via the Frew Publications website by clicking here.

I've had an article published in the recent edition of Giant Size Phantom comic (Number 2), released by Frew Publications (Australia).Giant Size Phantom is a showcase-styled magazine, which reprints some of Frew Publications' earlier Australian-drawn comics from the 1940s and 1950s, when Australia's comic-book industry was at its peak of commercial success Australia had a population of just over 9 million people back then, but Australians were reading 60 million comic books annually by 1954. Crikey!My first article for this magazine focuses on The Phantom Ranger, an Australian-drawn cowboy Western comic, which was tremendously popular back in the day.After they'd finished reading the latest issue of The Phantom Ranger comic book, Aussie kids could deck themselves out from head-to-toe in licensed Phantom Ranger clothing, and tune in to The Phantom Ranger radio serial, starring the late Australian actor, Charles "Bud" Tingwell.Australian readers can purchase their copies Giant Size Phantom (Number 2) online, via the Frew Publications website by clicking here.

Published on November 15, 2017 08:28

September 22, 2017

New Article on Romance Comics in Australia

I'm delighted to announce that my latest research on Australian comics appears in a new essay collection,

The Popular Culture of Romantic Love in Australia

. The book is edited by Hsu-Ming Teo (Macquarie University), and has just been published by Australian Scholarly Publishing (North Melbourne, VIC).

I'm delighted to announce that my latest research on Australian comics appears in a new essay collection,

The Popular Culture of Romantic Love in Australia

. The book is edited by Hsu-Ming Teo (Macquarie University), and has just been published by Australian Scholarly Publishing (North Melbourne, VIC).My contribution to this book is titled "Intimate Confessions: The Rise and Fall of Romance Comic Books in Australia" (pp.223-256). This chapter looks at the explosive popularity of romance comic books in post-war Australia, through to their gradual decline during the 1970s and early 1980s. The chapter considers the influence of American mass culture on Australian audiences' conception of "romantic love", given that many of the romance comics published in Australia were licensed reprints of American titles.

This chapter speculates about the relative dearth of Australian-drawn romance comics during this period, while comparing how locally-produced romance comics adhered to, or deviated from, the generic norms established by their American counterparts. It looks at how romance comics were one of the few examples where Australian comic-book publishers attempted to communicate directly with readers, and discusses who, in fact, read romance comics.

The book can be purchased for AU$39.95 directly from Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Published on September 22, 2017 13:30

April 26, 2017

Self-Censorship in Australian Comic Books

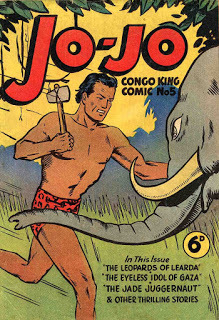

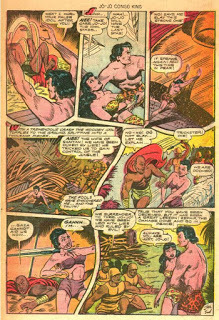

Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic, No.5 - 1948The year 1948 signaled the beginning of the comic-book "boom" in Australia, with dozens of new titles released onto the market every month, each one clamouring for shelf space in newsagents and railway bookstalls across the country. While some of these comics - maybe less than one-third - were written and drawn by Australian artists, the vast majority of them were licensed reprints of American comics, many of them never before seen by Australian audiences.

Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic, No.5 - 1948The year 1948 signaled the beginning of the comic-book "boom" in Australia, with dozens of new titles released onto the market every month, each one clamouring for shelf space in newsagents and railway bookstalls across the country. While some of these comics - maybe less than one-third - were written and drawn by Australian artists, the vast majority of them were licensed reprints of American comics, many of them never before seen by Australian audiences.American comic magazines were still subject to wartime-era import licensing restrictions, which meant they were prohibited imports, and could not be sold in Australia. American publishers, and their overseas sales representatives, sidestepped these restrictions by sending print-ready comic-book artwork (often supplied as printing matrices ["mats"]) to Australian publishers, who arranged to have them printed and distributed throughout the country.

While some of these Australian editions - such as Superman All-Color Comic - were published in full colour like their American counterparts, the majority of them were printed on cheap newsprint (including the cover), and the interior pages were reproduced in black & white. Due to the ongoing rationing of newsprint in the late 1940s, Australian publishers would often reproduce two pages of (American) comic-book artwork on a single printed page, in order to conserve their scarce newsprint stocks.

Australian publishers would frequently alter the contents of these American comics, in order to give the impression that they were, in fact, Australian-drawn comics. Hence, some companies went so far as to remove explicit references to American cities or states with recognisably Australian place names, or even substitute depictions of the American flag with the Australian flag. Local publishers would also by edit out American slang expressions, while references to dollars and cents were often replaced with the Australian equivalents of pounds, shillings, and pence. It is not known whether few, if any, young Australian readers were deceived by such practices.

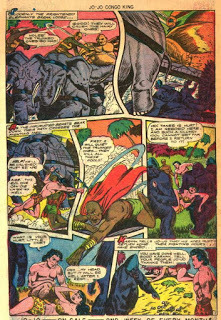

Sometimes, however, Australian publishers took steps to censor American stories considered too extreme for Australian audiences' tastes. Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic is one of the more interesting - and obvious examples - of the steps some Australian publishers took to tone down some of the more salacious American comics that were now available to local publishers.

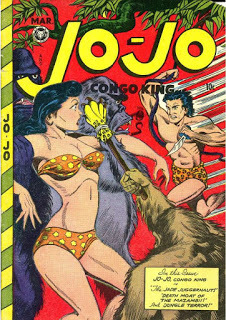

Jo-Jo Congo King, No.25 - March 1949

Jo-Jo Comics

was launched by Fox Features Syndicate (US) as an innocuous "funny animal" comic in Spring 1946. However, in keeping with the company's growing reputation for publishing excessively violent and sexually provocative superhero, crime and Western comics, the magazine was renamed Jo-Jo Jungle Comic with its seventh issue in July 1947. The titular character, Jo-Jo, was a musclebound Tarzan clone, who - like many of his comic-book peers - was given to spouting pseudo-Shakespearean dialogue (A laughable invocation of Rousseau's ideal of "the noble savage".)

Jo-Jo Congo King, No.25 - March 1949

Jo-Jo Comics

was launched by Fox Features Syndicate (US) as an innocuous "funny animal" comic in Spring 1946. However, in keeping with the company's growing reputation for publishing excessively violent and sexually provocative superhero, crime and Western comics, the magazine was renamed Jo-Jo Jungle Comic with its seventh issue in July 1947. The titular character, Jo-Jo, was a musclebound Tarzan clone, who - like many of his comic-book peers - was given to spouting pseudo-Shakespearean dialogue (A laughable invocation of Rousseau's ideal of "the noble savage".)Tanee was Jo-Jo's buxom female companion, and found herself frequently kidnapped, bound, tortured, or otherwise threatened by poachers, tribal warriors, and marauding apes. She occupied the foreground of the comic book's covers, posed provocatively in her jungle bikini costume. Jo-Jo's name might have been on the masthead, but Tanee was clearly the draw-card attraction, tempting adolescent males to part with their hard-won dimes.

Young's Merchandising Ltd. (Sydney) acquired the Australian publication rights to several Fox Feature Syndicate titles, including Jo-Jo Congo King, which they released sometime in 1948 (It is not known whether Young's Merchandising purchased the rights directly from Fox Features Syndicate, or through foreign intermediaries, such as Transworld Feature Syndicate, which marketed American comics to many foreign countries after World War Two).

Young's Merchandising opted to commission new cover illustrations by local (uncredited) artists, perhaps sensing that the original American covers for Jo-Jo would be considered too provocative for Australian readers' tastes or, rather, Australian parents' tastes. Their conservatism was not necessarily shared by rival publishers; H.J. Edwards Pty Ltd (Sydney) did not hesitate to reuse the original American covers for its licensed reprints of Fiction House (US) comics, such as Jungle Comics, Sheena Queen of the Jungle, and Jumbo Comics.

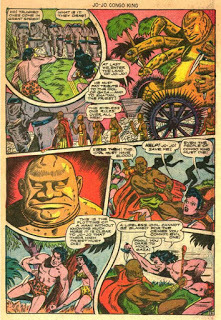

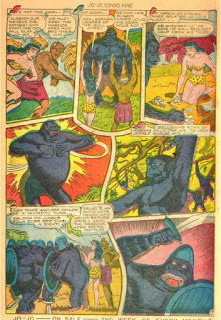

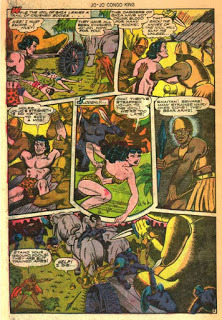

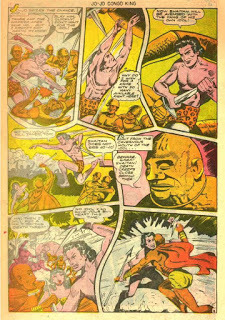

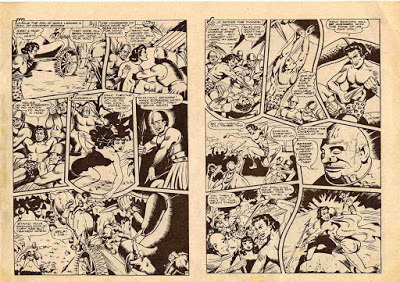

Young's Merchandising Ltd. also took steps to censor some of the more explicit scenes of violence, and modify some of the more revealing costumes worn by the female characters. This is abundantly clear in the Australian edition of Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic, No.5 (published in 1948), which reprinted the story, "The Eyeless Idol of Gaza", originally published in the American edition of Jo-Jo, Jungle King, No.12 (March, 1948). Judging by the story's title, the uncredited writer concealed by the pseudonym "Stan Ford" was clearly an Aldous Huxley fan!

Young's Merchandising Ltd. also took steps to censor some of the more explicit scenes of violence, and modify some of the more revealing costumes worn by the female characters. This is abundantly clear in the Australian edition of Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic, No.5 (published in 1948), which reprinted the story, "The Eyeless Idol of Gaza", originally published in the American edition of Jo-Jo, Jungle King, No.12 (March, 1948). Judging by the story's title, the uncredited writer concealed by the pseudonym "Stan Ford" was clearly an Aldous Huxley fan!For starters, Young's Merchandising did not use the original cover (See image at left), opting for the far tamer scene showing Jo-Jo charging an elephant, clutching a stone mallet in his fist (See image at beginning of this post). Tanee's jungle bikini costume has also been painted over throughout the comic, and replaced with a more modest one-piece dress, which nevertheless shows off her shapely figure.

But as you will see in the following visual comparison, Young's Merchandising censored some of the more explicit scenes of violence contained in the original American version.

"Eyeless Idol of Gaza" - US version (Pg.1)

"Eyeless Idol of Gaza" - US version (Pg.1)

"Eyeless Idol of Gaza" - US version (Pg.2)

"Eyeless Idol of Gaza" - US version (Pg.2) "Eyeless Idol of Gaza" - Australian version (Pages 1 & 2)

"Eyeless Idol of Gaza" - Australian version (Pages 1 & 2)

The Australian edition of Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic, did not outlast its American originator, with both editions ceasing publication in 1949. Young's Merchandising published only a fraction of the stories which appeared in the American version of Jo-Jo,Congo King, which ran for 23 issues during 1947-49. Young's Merchandising launched the Australian version of Jo-Jo at a time when the local comic-book market was being flooded with dozens of new titles every month, especially once wartime newsprint rationing laws were lifted. This fact alone would have made it hard for Jo-Jo, Congo King Comic, to stand out on crowded newsstands.

Yet even by the crude editorial standards of American comic books, Jo-Jo may have simply been no match for the proven popularity of other American "jungle hero" comics available to Australian readers at the time, such as Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, or even The Phantom. Stripped of the blood-thirsty violence and sexual titillation that were the hallmark of Fox Features Syndicates' comics, Jo-Jo was little more than a cheap Tarzan "knock-off", overshadowed by the reigning kings and queens of Australia's "comic-book jungle".

Images courtesy of Comic Book + and the Rare Books Collection at Monash University Library (Melbourne, Australia).

Published on April 26, 2017 02:05

December 28, 2016

Arthur Mather - Life with Captain Atom, and Beyond

NOTE: I was fortunate enough to interview Arthur Mather, co-creator of the Australian superhero, Captain Atom, at his Melbourne home in 2003. A heavily-edited version of my interview appeared in my "Comics Down Under" column, published in the February 2005 edition of Collectormania magazine (Australia). An expanded version of that article, based on my interview with Mather, was published online at PulpFaction.net in February 2005. However, when PulpFaction.net was closed down in October 2013, my article could only be retrieved (with some difficulty) via the Internet Archive search engine.

Given the historical significance of Mather's contribution to Australian comics history, and in recognition of his latter career as an author of popular thriller novels, I thought this was an opportune time to revise and update this piece, and make it the closing entry on this blog for 2016 - a year which has, sadly, witnessed the death of several key writers and artists from the "Golden Age" of Australian comic books.

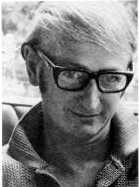

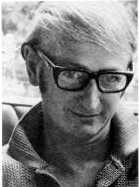

Arthur Mather, 1975“Get a trade behind you.” For the generation of Australian men who had been scarred by the Great Depression of the 1930s, this was the only path towards secure employment and one that many insisted their sons pursue.

Arthur Mather, 1975“Get a trade behind you.” For the generation of Australian men who had been scarred by the Great Depression of the 1930s, this was the only path towards secure employment and one that many insisted their sons pursue.

Arthur Mather’s father, a furniture upholsterer raising his family in the inner Melbourne suburb of North Fitzroy, was no exception. “I finished school at Collingwood Technical School and my father, who saw the worst of the Depression, insisted I get a trade,” he recalls.

Arthur, however, had other ideas. An imaginative child, he was always drawing and making up stories, when he wasn’t poring over the popular newspaper comic strips of his childhood, such as Tim Tyler’s Luck, which was one of his favorites.

“I was also a great fan of David Low’s work, who was probably the most famous political cartoonist Australia turned out,” says Arthur. “I told my dad I wanted to be a cartoonist, but he said there was no living to be made in being a cartoonist.”

Arthur left school in 1940 and, at 14 years-of-age, seemingly followed his father’s wishes by becoming a printing apprentice at The Truth , a racy Melbourne tabloid newspaper that also did printing for other newspaper and magazine publishers - including the Australian Army Education Service's wartime magazine, SALT .

“This didn’t stop me from being a cartoonist,” according to Arthur. “While I was working as an apprentice, I used to draw political and joke cartoons for other Melbourne newspapers, as well as national magazines.”

These freelance assignments included weekly cartoons for a long-defunct Melbourne newspaper, The Mid-day Times, before Arthur became a sporting cartoonist for his employer, The Truth newspaper. It was while working as an apprentice that Arthur met the man who would eventually help launch him on a new career as a comic book artist: Jack Bellew.

Jack Bellew(1901-1957) was a well-known Sydney journalist and former Editor-in-Chief of the Daily Telegraph, the premier newspaper of Sir Frank Packer’s Consolidated Press publishing empire.

Towards the end of World War Two, Bellew, who had now relocated to Melbourne, visited The Truth to arrange the printing for a new current affairs magazine he was to edit with John Sinclair, called Tomorrow – The Outspoken Monthly.

“It was just one of those extraordinarily lucky things,” according to Arthur. “I was up in the composing room and the foreman of the composing room was talking to this chap about his magazine and he said ‘Jack, Arthur’s a cartoonist, so if you want some cartoons for your magazine, he’ll do them for you.’”

Arthur contributed cartoons to the short-lived Tomorrow magazine (March-December 1946) and thought no more about it, until Jack Bellew later called him at home. "He had an office in Queen Street and he said ‘I’d like you to come in – we’ve got an idea you might be interested in’” recalls Arthur.

After the demise of Tomorrow, Jack Bellew, together with his former Consolidated Press colleagues, George Warnecke and Clive Turnbull, had decided to form their own publishing company, Atlas Publications.

With the Commonwealth Government’s wartime ban on imported periodicals (which included comic books) still in place, Bellew decided to launch a new comic book in what he saw as “very dry market.”

“We’d like to do something about the atomic age, which is all the thing now – ‘Atom Man’ or ‘Captain Atom’,” Bellew told Arthur. “Would you like to go away and do some drawings?”

“We could get an artist in Sydney to do this, but it would cost us a fortune,” Bellew continued, “but you’re just starting out, so if you really want to be a cartoonist, here’s your big chance.”

“I didn’t have to be told twice!” says Arthur, who promptly went and drew up 3 or 4 sample pages featuring his first ever comic book superhero – Captain Atom.

Captain Atom, No.1, January 1948Captain Atom, according to the late Australian comics historian, John Ryan (1931-1979), blended dramatic elements from popular American comic book superheroes of the era. Writing in his pioneering history of Australian comics,

Panel by Panel

(1979), Ryan described Mather's atom-age hero as follows:

Captain Atom, No.1, January 1948Captain Atom, according to the late Australian comics historian, John Ryan (1931-1979), blended dramatic elements from popular American comic book superheroes of the era. Writing in his pioneering history of Australian comics,

Panel by Panel

(1979), Ryan described Mather's atom-age hero as follows:

'Drawn in a crude by fascinating style by Arthur Mather, the character combined the "magic word" (Exenor!) gimmick from Captain Marvel, and the twin brothers ploy from (K.G.) Murray's Captain Triumph, and shrouded it with the mystique of the atom bomb explosion of Bikini Atoll, still fresh in people's minds. The first dozen or so scripts were by Ballieu [sic] who used the nom-de-plume "John Welles", then passed on the writing chores to Mather.'

“I took them into him and he said ‘This is exactly what we’re looking for’,” according to Arthur.

“He’d written the first [story] and gave me the script for me to draw,” he says. “I’d just finished my apprenticeship, so I could get away and set myself up at my parents’ home.”

“I finished drawing [the first story] and said ‘What do you think?’ and they say said that’s just what they wanted. I’d say they were influenced by the popularity of Superman and Batman.”

Superman and Batman were, in fact, setting new sales records for locally published comic books. Sydney’s K.G. Murray Publishing Company has acquired the Australian rights to reprint DC Comics' American titles, commencing with Superman All Color Comic, which was posting record-breaking sales of of 150,000 copies per issue, shortly after its debut in 1947.

The following summary from the entry on Captain Atom from the International Hero page highlights the character's similarities to Captain Marvel and Captain Triumph:

After an A-Bomb blast fused Dr.Bikini Rador with his twin brother, the scientist discovered he could swap places with his now-super-powered sibling by exclaiming "Exenor!" Wanting to use this new ability for the greater good, Bikini would adventure under the alias Larry Lockhart, ace F.B.I. agent, then summon his brother, now using the name Captain Atom, when things got too hot for a normal man to handle.

Captain Atomalso became one of the first Australian-made comic books to be published in full-color. “That was done with a color overlay,” says Arthur. “I would draw it in black and white then, with a transparent sheet overlay, the colors would be indicated on that.”

Newspaper News, November 1, 1948The first issue of

Captain Atom

, published in January 1948, was a roaring success, selling over 100,000 copies. By the end of its first year of publication, Atlas Publications claimed Captain Atom had sold over one million copies nationwide, and announced plans to produce a newspaper comic-strip version - a project which, sadly, never eventuated.

Newspaper News, November 1, 1948The first issue of

Captain Atom

, published in January 1948, was a roaring success, selling over 100,000 copies. By the end of its first year of publication, Atlas Publications claimed Captain Atom had sold over one million copies nationwide, and announced plans to produce a newspaper comic-strip version - a project which, sadly, never eventuated.

“This was what they [Bellew, et. al.] hoped to use as a seed-bed for their publishing company,” says Arthur, “for the publishing of high quality magazines – at least, that’s where they were aiming.”

Captain Atom continued to grow in popularity, spawning a line of merchandise (including a glow-in-the-dark Captain Atom ring), as well as a Captain Atom Fan Club, which had over 75,000 members at the peak of the character’s popularity.

Unlike American comic books of the time, which were created by several artists working on different aspects of each story, Arthur Mather was solely responsible for each entire Captain Atom episode.

“I used to write a synopsis and I’d show it to Jack,” says Arthur. “He’d look at it and usually say ‘Fine’, then I’d go away and write the rest just for myself – dialogue, captions, action directions – just in longhand.”

“I used to knock the script off in a day or two, then I’d pencil it in first.” He says. “I was penciling in the morning, then I’d ink them in the afternoon – then I’d collapse!”

“You do get incredibly fast when you do something like that,” says Arthur, “but I was much younger then!”

Captain Atom, No.47 - Story & Art by Arthur MatherDespite the workload, Arthur enjoyed it all: “I thought it was great to be actually doing it – it’s what I wanted to do all my life and now I was.”

Captain Atom, No.47 - Story & Art by Arthur MatherDespite the workload, Arthur enjoyed it all: “I thought it was great to be actually doing it – it’s what I wanted to do all my life and now I was.”

The early issues of the Captain Atom comic book also featured back-up strips, including Jim Atlas and Dr. Peril of Iggo, by Sydney artist Stanley Pitt, who would later go on to create the influential science fiction comic strip, Silver Starr.

Michael Truemancontributed several supporting strips as well, including Terry Flynn, Big Paul, ‘Two-Gun’ Barrel, Wildfire McCoy, Dick Hawke and Crackajack Daredevil.

“I remember Stanley Pitt, although I don't recall him working for Atlas” says Arthur. “However, I do remember Michael Trueman, certainly – he was a good artist, but I’ve no idea whatever happened to him.”

"Crackajack", by Michael Trueman

"Crackajack", by Michael Trueman

(Captain Atom, No.10, 1948)The first 16 issues of Captain Atom were published in color, before it was converted to the standard black and white format typical of virtually all Australian comics of the era: “Atlas Publications stopped producing Captain Atom in color because it was too expensive for the price.”

The character proved sufficiently popular to withstand the switch and continued to be a strong seller, racking up 63 issues before concluding around 1957.

Just as Captain Atom was switching to the black and white format, Atlas Publications was expanding its comic book line throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s. These included Australian comic book reprints of American and British newspaper comic strips, including Garth, Jimpy, Johnny Hazard, Rusty Riley, Jane Arden and Red Ryder.

The overseas reprints were joined by new, locally-created, comic-book series, including the Western cowboy, The Lone Wolf , created by Keith Chatto, a masked crime fighter called The Grey Domino and another Western gunslinger, The Ghost Rider, both of which were drawn by Terry Trowell.

Some of Atlas Publications’ reprint comics began with the original overseas artwork, before being passed on to local artists, who would create all-new stories featuring the existing characters. One example of this curious trend was Brenda Starr , which started out reprinting the original newspaper strip installments by its American creator Dale Messick, before being passed on to Australian artists, such as Yaroslav Horak.

Brenda Starr, No.31 - Cover art by Yaroslav Horak“I regard Yaroslav as the finest comic strip talent to ever work in this country,” says Mather. “Not in the fine art sense, but in the comic-book style, with the dramatic use of black developed by the great Milton Caniff.”

Brenda Starr, No.31 - Cover art by Yaroslav Horak“I regard Yaroslav as the finest comic strip talent to ever work in this country,” says Mather. “Not in the fine art sense, but in the comic-book style, with the dramatic use of black developed by the great Milton Caniff.”

“To attest to Yaroslav’s talent, he went to London and won international fame illustrating the James Bond newspaper strip for London’s Daily Mail," he adds. “A wonderful strip and drawn with Yaroslav’s exceptional talent.”

Arthur Mather inherited two American comic strip characters in a similar fashion:

Sgt. Pat of the Radio Patrol and Flynn of the FBI.

Sgt. Pat of the Radio Patrol originally began as a newspaper comic strip called Radio Patrol , created by two employees of the Boston Daily Record, Eddie Sullivan (writer) and Charlie Schmidt (artist). Although well regarded by critics today, Radio Patrol never enjoyed the huge success of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy, the strip it was most frequently compared to, during its American newspaper run between 1933-1950. Sgt. Pat did, however, enjoy a longer life under the Atlas Publications banner, running for 79 issues until the late 1950s.

The first 30-40 issues contained reprints of the original American newspaper strip, before the comic was initially passed on to Yaroslav Horak, followed by another Australian artist, Andrea Bresciani, before Arthur Mather took over the title.

“Andrea Bresciani was another very good artist – he was a very natural talent,” according to Arthur. Bresciani, who originally drew the Tony Falco comic book in his native Italy in 1948-49, immigrated to Australia in the 1950s, where he worked for several local publishers, before illustrating the acclaimed newspaper strip, Frontiers of Science , written by Bob Raymond, in the early 1960s.

“Flynn of the FBI may have been originally a newspaper strip, because I know I didn’t create the character,” recalls Arthur.

The first two issues of Flynn of the FBI contained reprints of the American comic strip, Secret Agent X-9, which was created by acclaimed crime novelist, Dashiell Hammett, and illustrated by Alex Raymond, for King Features Syndicate (US) in 1934.

However, when Hammett and Raymond ceased working on the series in 1935, the comic was subsequently assigned to authors Leslie Charteris (creator of The Saint ) and "Robert Storm" - the latter, according to the Newspaper Comic Strips website, being a "house name", or script-writing credit employed by King Features Syndicate. It was during this period that the character was recast as a Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) agent, and was drawn by Charles Flanders until 1938, before Flanders, too, found greater fame illustrating The Lone Ranger comic strip, commencing in 1939.

Flynn of the FBI, No.13 - Arthur Mather coverIt is not known why Atlas Publications chose rename this comic strip Flynn of the FBI - perhaps the alliterative title sounded more catchy to the Australian publisher's ears? If nothing else, it evoked the name of the Australian-born Hollywood star, Errol Flynn. Mather, however, remains unsure about why Atlas Publications decided to use local artists to illustrate overseas comic strips: “A lot of that stuff at Atlas would have passed me by, because I was working from home at the time. The only time I ever went [to their offices] was to take stuff in.”

Flynn of the FBI, No.13 - Arthur Mather coverIt is not known why Atlas Publications chose rename this comic strip Flynn of the FBI - perhaps the alliterative title sounded more catchy to the Australian publisher's ears? If nothing else, it evoked the name of the Australian-born Hollywood star, Errol Flynn. Mather, however, remains unsure about why Atlas Publications decided to use local artists to illustrate overseas comic strips: “A lot of that stuff at Atlas would have passed me by, because I was working from home at the time. The only time I ever went [to their offices] was to take stuff in.”

“[It] may have been originally a newspaper strip, because I know I didn’t create the character - but I certainly wrote and drew Flynn of the FBI at the time,” he says. “I didn’t have to follow any guidelines, so I did it as I saw fit.” Mather took over writing and illustrating the comic with its third issue, and remained on the title until it cased publication in the late 1950s.

Science-Fiction Monthly, No.16, 1957Comic books were just one part of Atlas Publications’ rapidly expanding line of magazines, which included Squire, a men’s magazine based on the American Esquire, along with joke books like Frolic, which also featured occasional "pin-up girl" cartoons by Arthur Mather. The company also branched out into pulp-fiction magazine series, including Science-Fiction Monthly, King-Colt Western, and Crime Mysteries.

Science-Fiction Monthly, No.16, 1957Comic books were just one part of Atlas Publications’ rapidly expanding line of magazines, which included Squire, a men’s magazine based on the American Esquire, along with joke books like Frolic, which also featured occasional "pin-up girl" cartoons by Arthur Mather. The company also branched out into pulp-fiction magazine series, including Science-Fiction Monthly, King-Colt Western, and Crime Mysteries.

Comic books like Captain Atom may have helped get Atlas Publications off the ground, yet by no means were the company’s founders entirely proud of them.

“I don’t think even Jack Bellew or Clive Turnbull liked to be associated with the idea of comic books,” says Arthur. “While we were never censored, there was a real campaign against comics [during the 1950s], with people claiming they were ‘undermining the morals of the young’. It was ridiculous, even then!”

It was during this period of Atlas Publications’ rapid expansion that Arthur found his working relationship with Jack Bellew becoming increasingly strained.

Frolic - Cartoon by Arthur Mather, 1950s“When we first started, it was a lot of fun,” he recalls. “I can remember Jack had a great laugh and we’d go in there and tell him jokes, throw ideas around – there’d be lots of jocularity.”

Frolic - Cartoon by Arthur Mather, 1950s“When we first started, it was a lot of fun,” he recalls. “I can remember Jack had a great laugh and we’d go in there and tell him jokes, throw ideas around – there’d be lots of jocularity.”

“As the company got bigger, we really lost that,” says Arthur. “By now he was the Managing Director, so my work no longer went through him, I’d have to go through an editor.”

Atlas Publications’ biggest attempt to enter mainstream magazine publishing would eventually prove to be both Jack Bellew’s and the company’s undoing.

The Pharmaceutical Guild of Australia, in 1955, contracted Bellew’s former employer, Consolidated Press, to print Family Circle, a monthly magazine to be sold through pharmacies across the country.

Jack Bellew and George Warnecke took over the production of the magazine, but Family Circle did not prove to be the financial success that Atlas Publications’ founders hoped it would be.

“The strain and the stress really killed [Jack],” says Arthur. “He was of an age, when you’ve got to a point in your life where you think you’ve done it all and you can’t get up and run again.”

“There was a Christmas break-up party and someone said to me, ‘This is all a joke, the company’s going to go bust’,” he says, “which it did.”

Jack Bellew died in 1957, shortly after which Family Circle ceased publication, while the entire Atlas Publications business appears to have collapsed some time in 1958 (Family Circle was relaunched with far greater success as a monthly periodical in 1973, but has gradually been scaled back to a bi-annual publishing schedule for the last 15 years or so by its current publisher, Pacific Magazines).

Atlas Publications’ demise may have ended Arthur Mather’s comic-book career, but he was not ready to give up on comics entirely.

Mather had, by this time, already begun branching out into the newspaper comic-strip field. In January 1955, he created Andy Handy, a weekly humorous strip about a suburban handyman, for The Argus newspaper (Melbourne), inspired by his own experience of renovating his family home.

Mather subsequently got together with a friend of Jack Bellew, the Sydney journalist Harry Cox, who had previously worked for The Sun (Sydney), and later became the managing editor of the outspoken newspaper, Smith’s Weekly .

Mather told Cox that one of Melbourne’s daily newspapers might be interested in running a new daily detective comic strip. He asked Cox if he would be interested in writing it: “I thought it would have had more chance with Harry Cox writing it than with me writing it.”

“I think I did about two or three months’ worth [of sample artwork] and we took into The Sun News Pictorial and they said they were very interested,” recalls Arthur.

“You know the business and you know how daily papers operate more than I do,” Mather told Cox, “so I’ll leave it to you to go and arrange the deal.”

“He came back and told me they liked the strip and they were going to do all the [printing] plates and proof it up on art paper,” says Arthur.

“What did you ask for it,” he recalls, “and Harry said ‘Oh, I thought about £80 per week’ – this was at a time when people were earning £6 or £ 7 per week! I said that’s a bit much, but Harry said ‘Oh, they can afford it’ – but they turned it down flat, just on the money!”

“I turned my back on comics from there,” according to Arthur. “I just wasn’t going to do that anymore, because I worked for about 3-5 months, for no money at all – and I couldn’t afford to do that, especially as I had a young family to support.”

The arrival of television in Australia in 1956 not only changed the leisure habits of Australian households, but it also had a detrimental impact on the fortunes of local cinemas, radio stations, newspapers and book and magazine publishers – all of which, initially at least, lost a big chunk of their established audience to television.

Television played a significant part in hastening the end of Australia’s indigenous comic book industry, but it also provided new opportunities for Arthur Mather.

“I did a children’s program for Channel Two, about a little aboriginal boy, all done with cardboard puppets,” he recalls.

“The show was called Brogli and it was a big hit,” says Arthur. “It was a lot of work, though, because you had to make a lot of cardboard characters and do it live on camera.”

Brogliran for nearly 18 months on Channel Two (operated by the government-owned Australian Broadcasting Commission), before Mather took the show to a rival commercial station, Channel Seven, where it ran for another six months or so.

Once Brogliceased broadcasting, Mather got a job as a layout artist with Melbourne’s Herald & Weekly Times’ magazine publishing department, before responding to an advertisement for a layout artist’s position with the advertising agency, J. Walter Thompson.

“I went in and got the job,” says Arthur, “and I sort of fell into the advertising world fairly easily.”

Over the next 20 years, Mather held senior positions with some of Australia’s biggest advertising agencies. He eventually became Art Director at J. Walter Thompson’s (“I enjoyed that and had some big accounts there, including MacRobertson’s Chocolate”), before accepting a generous offer to join D’arcy Masius (“The agency just didn’t work out for me.”)

“Then I went to George Patterson’s,” says Arthur. “By the time I finished working there, I was Senior Creative Director.”

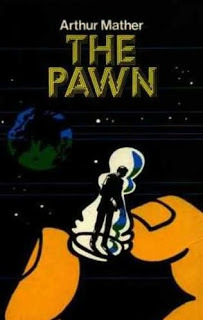

George Patterson’s was to be Arthur’s last agency in the advertising industry. It was while working there that he wrote a dystopian science fiction novel, The Pawn, which was published in 1975.

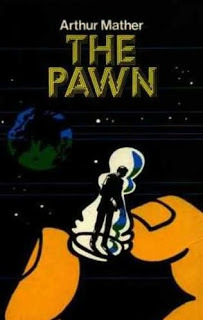

The Pawn, by Arthur Mather, 1975“Dennis Wren, of Wren Publishing, God bless him, loved it,” says Arthur. “I got these fantastic reviews and it sold pretty well at the time.”

The Pawn, by Arthur Mather, 1975“Dennis Wren, of Wren Publishing, God bless him, loved it,” says Arthur. “I got these fantastic reviews and it sold pretty well at the time.”

Emboldened by the critical success of The Pawn, Arthur decided to retire from the advertising world in the early 1980s. “I thought it was time for me to do something different,” he says, “so I decided to give it a go as a full-time writer.”

The first thing Arthur did was to send the manuscript for The Pawn to William Morris, a huge literary agency in New York City: “They sent it back to me in the same package – unopened!”

“When The Pawnwas published [in Australia], I sent the published book back to a contact I had there, a lady named Rhoda Weyr,” recalls Arthur.

“I sent it with a note saying, ‘This is the book you didn’t open’,” he adds. “She read it, liked it and said ‘If you do anything else, send it to me’.”

Arthur took her up on the offer, sending Rhoda the manuscript for his next novel, a thriller called Easy Money.

“In some respects, Easy Money was as good as I ever did,” he says, “and [Rhoda] was really over the moon about it.”

Easy Money (1979) was sold to Delacorte Press in America, as well as being picked up by the UK literary agent Ed Victor (“He handled every top writer in the UK”), who in turn sold it to the British publishers Hodder & Stoughton. Easy Money, by Arthur Mather, 1979

Easy Money, by Arthur Mather, 1979

“Then there was my next book, called The Mind Breaker (1980), which Ed Victor was also very keen on and he also sold that to Hodder,” says Arthur.

“It went from Hodder in the UK, to Rhoda in New York and she sold it to Delacorte Press, who published it in hardcover,” he says, “but it only sold around 20,000 copies.”

It was during this time that Arthur had a falling out with Rhoda Weyr. “I’m not sure how it happened,” he says, “but she would see things in manuscripts that she said required altering which seemed quite odd to me – and to a number of other people.”

Arthur soon signed up with a new literary agent, Roslyn Targ, whom he describes as “one of the nicest Americans I’ve ever met – and she’d work her butt off for you.”

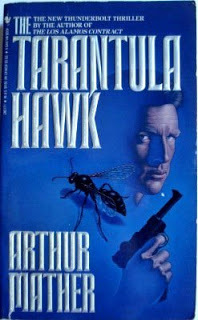

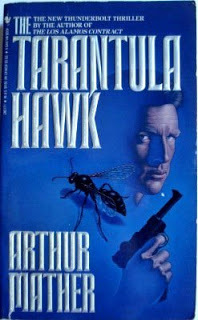

She took all of Arthur’s next five books: The Duplicate(1985), Deep Gold (1986), The Raid (1986), The Los Alamos Contract (1986) and The Tarantula Hawk (1989). “[Roslyn] had a good connection with Bantam Books in New York, who published them all,” says Arthur.

The Tarantula Hawk, by Arthur Mather, 1989All of Mather’s books are taut, exciting thrillers, which usually revolve around plots that are partly based on historical incidents or technical facts, such as new technologies or scientific advances.

The Tarantula Hawk, by Arthur Mather, 1989All of Mather’s books are taut, exciting thrillers, which usually revolve around plots that are partly based on historical incidents or technical facts, such as new technologies or scientific advances.

“I’ve always been a reasonably imaginative person,” says Arthur, “which is why I find it easy to write thrillers, I suppose.”

“I’ve always liked thrillers and I think The Day of the Jackal [by Fredrick Forsyth] is a masterpiece of the thriller genre,” he says, “but I also read other things, like Bertrand Russell.”