Elizabeth Bell's Blog, page 3

May 6, 2020

What’s in a (Character) Name?

In Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare famously wrote:

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title.

But he gave those words to a lovestruck teenager. I suspect Shakespeare himself felt differently, that all writers do. Names matter. It matters whether you call someone “a slave” or “an enslaved person.” It matters whether you call a person Zizistas (their name for themselves, which means “the People”) or Cheyenne (another tribe’s name for them, which means “we do not understand their language”). It even matters what you call a rose, as my character Joseph discovers in Lost Saints.

The rose called Maiden’s Blush—or less demurely, Cuisse de Nymphe Émue. If you don’t speak French, plug that into Google Translate for a rough idea of why it’s naughty. For a better translation, read Lost Saints.

The rose called Maiden’s Blush—or less demurely, Cuisse de Nymphe Émue. If you don’t speak French, plug that into Google Translate for a rough idea of why it’s naughty. For a better translation, read Lost Saints.

April 3, 2020

When the Research Rabbit Hole Leads You Back Home

It’s funny how I’ll puzzle over a story problem for months only to realize that the answer has been all but staring me in the face. Although most of my historical series, the Lazare Family Saga, is set in South Carolina and (what is now) Wyoming, I live in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C. That will soon be relevant. Journey down the research rabbit hole with me…

The Lazare Family Saga grapples with racism and slavery in the antebellum American South. Sweet Medicine, the fourth and final book, takes the characters into the Reconstruction era after the Civil War. I had to figure out what the Lazare family should be doing during this momentous period in American history, something that would make a fitting capstone to my saga and “bring it all together.”

The title of Book 4, Sweet Medicine, has multiple meanings. One of these is literal: two Lazares are medical doctors. Another meaning is figurative, referring to spiritual healing. For one particular character (I’m being deliberately vague to minimize spoilers), I wanted his Reconstruction choices to encompass both literal and figurative healing. Although he is a physician dedicated to helping others, he is himself psychologically wounded.

I wanted this character to be involved in educating newly freed African-Americans as a way of reclaiming his ancestry and healing his fractured identity, since the Lazares are a multiracial family who have been “passing” as white for most of the series. Before Emancipation, penalties for teaching an enslaved person to read included imprisonment and hefty fines. An enslaved person caught with a book would be whipped and often sold because his/her master considered an educated slave dangerous. Both during and after slavery, when an African-American learned to read, it was a way of declaring his/her personhood, of declaring that (s)he was worthy of more than manual labor. During Reconstruction, whole families—from children to grandparents—eagerly attended classes. After the devastation of slavery, education provided a means for African-Americans to heal themselves spiritually. White supremacists understood the symbolic and practical importance of education and frequently targeted schools and teachers.

But how could I pair this pro-education idea with literal medicine? The Reconstruction part of my story appears as an Epilogue. I don’t have fully fleshed out scenes to go into great detail. My characters’ Reconstruction choices must pack a satisfying emotional punch within a few paragraphs. Since the character in question commits a felony in South Carolina earlier in Sweet Medicine, I had to keep him away from that state. Beyond this limitation, the possibilities were mind-boggling. This is the part of historical fiction where the author conducts much more research than she’ll ever use, because she needs to eliminate possibilities.

At first, I placed my character at Hampton Institute. Today, this is Hampton University, located in my adopted state of Virginia but a solid 2.5 hour drive from me. I liked that enslaved people first escaped to Union lines near Hampton. I liked that Hampton University continues to thrive today, one of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities a.k.a. HBCU (meaning their student bodies are primarily African-American). But there was no medical connection with Hampton.

Another central subject in my work is Native Americans. They too were educated at Hampton, which would seem to be a vote in its favor. However, Hampton was one of the colleges where the white teachers sought to “kill the Indian, and save the man”—in other words, to strip the Native students of their culture.

Even with its black students, Hampton focused on vocational and agricultural degrees. This was actually called “the Hampton Idea.” Instead of being offered a “higher education,” students were trained to do manual labor because many white people thought freedmen were not (yet) intellectually capable of more cerebral careers. Even black people like Booker T. Washington advocated the Hampton Idea, which argued that African-Americans should “stay in their place,” accept racial segregation, and not expect to become social equals with white people. By placing my character at Hampton Institute, I felt I would be endorsing harmful prejudices.

So where should I place my character during Reconstruction? As it turns out, I have lived near the solution for over a decade and have borrowed books from its library many times: Howard University in Washington, D.C. I knew Howard was also one of the HBCU. I vaguely knew it was founded just after the Civil War (1867). But I didn’t realize how special Howard was.

Howard consisted of multiple colleges from the beginning: law, theology, normal (for training teachers), and medicine. Its founders understood that given an equal chance, African-Americans are every bit as capable of succeeding in intellectual professions as white people.

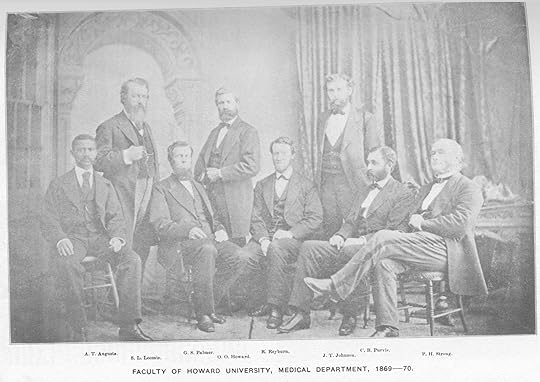

Not only that, Howard’s advanced curriculum was open to all races and both sexes from its 1867 founding. Howard admitted at least a few Native American students. Two of its medical professors in the 1870s were men of color, and one professor was a white woman. The #1 fear of white supremacists is black men intermingling with white women—and that very “amalgamation” was happening at Howard during Reconstruction.

Considering the segregation to come, Howard University circa 1870 was ahead of its time and Too Awesome Not to Use. Eureka! I’d found the perfect capstone to my family saga—practically in my own backyard.

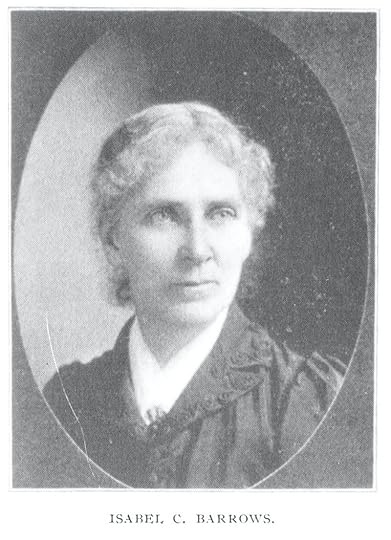

Dr. Isabel C. Barrows earned her degree at Woman’s Medical College of New York City in 1869 and also studied in Vienna, Austria. She was a professor in Howard University’s Medical Department from 1870-1873 (a year too late to appear in the below group photo). She specialized in diseases of the eye and ear.

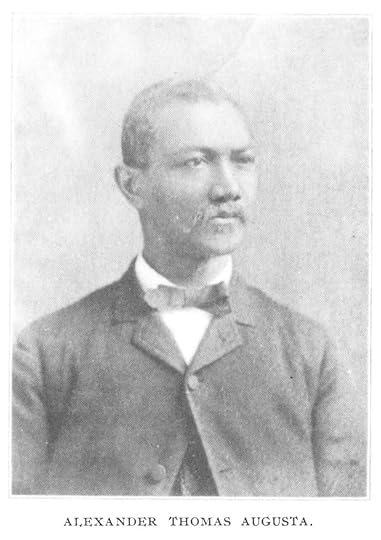

You might notice that the professor on the far left is a man of color, Dr. Alexander T. Augusta. In fact, so is the second man from the right, Dr. Charles B. Purvis.

You might notice that the professor on the far left is a man of color, Dr. Alexander T. Augusta. In fact, so is the second man from the right, Dr. Charles B. Purvis.

Dr. Alexander T. Augusta was born to free black parents in Norfolk, Virginia. He earned his degree at Trinity Medical College in Toronto, Canada in 1856. He was the first black medical officer during the Civil War, commissioned as a major and appointed head surgeon of the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry. Dr. Augusta was also the first black hospital administrator in the United States; the first black medical professor, teaching at Howard from 1869-1877; and the first black officer buried at Arlington National Cemetery (1890). You can see a photograph of him looking dashing in his Union uniform here.

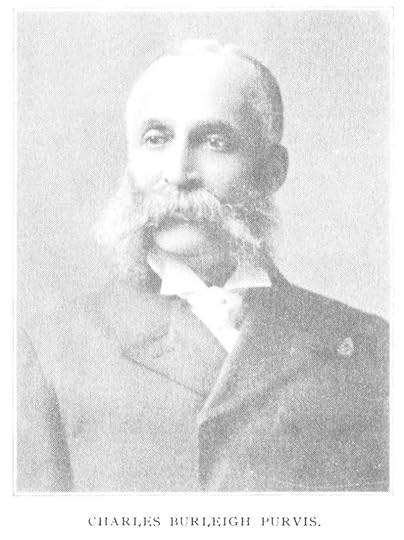

Dr. Charles B. Purvis was born to free black abolitionists in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He served as both a nurse and a surgeon during the Civil War and earned his degree at Wooster Medical College in 1865. Dr. Purvis was a professor in Howard’s Medical Department from 1869-1907. After the Financial Panic of 1873, the university was in dire straights and could no longer pay its faculty. Dr. Purvis continued teaching without a salary for three decades because he believed in Howard’s mission. Without him, the medical school probably would not have survived.

You’ll notice from these photographs that Dr. Purvis could have passed as white. He identified as black and was refused admittance to the American Medical Association because of it. Dr. Purvis’s father, Robert Purvis, was born in Charleston, South Carolina and was active in the Underground Railroad. Finding him was another lovely “full circle” moment in my research, a real-life echo of my fictional Lazare family.

All images in this post taken from the book Howard University Medical Department: A Historical, Biographical, and Statistical Souvenir by Dr. Daniel Smith Lamb, published in 1900. You can view the book in its entirety here: https://dh.howard.edu/med_pub/1

For the history of Howard as a whole, check out Howard University: the First Hundred Years, 1867-1967 by Ralph W. Logan, published in 1969.

March 11, 2020

Why Go Indie?

The short answer is: I had no choice.

The slightly longer answer: If I hadn’t, you wouldn’t know my novels exist.

But let’s back up a moment. You may be asking yourself not why but “what is indie?” It’s a term that’s also used in music and film. “Indie” means “this artwork is independently produced; it isn’t bankrolled by a large company and isn’t beholden to their demands.” Indie artists are usually a little different; we don’t quite fit the mold demanded of our contracted colleagues.

In my case, “indie” is short for “independent author.” This is our preferred identifier because it signifies that we are professionals. We don’t just slap a first draft on Amazon and expect the adoring public to flock to it. It’s fine to call us self-publishers, but don’t call us vanity publishers. We know our work has worth, but we can also take constructive criticism. We know we can’t do it all by ourselves. We have editors and cover designers. We have printers, but we are our own publishers. We’ve cut out the middle man between ourselves and our readers.

Now, for the why. At the age of fourteen, when I vowed to become a published author, I thought I’d be “traditionally published” by a major press. I thought I’d have a literary agent who’d be like my fairy godmother. I thought the title pages and spines of my novels would say Hachette or St. Martin’s. I thought my novels would be in brick and mortar bookstores. I thought my publisher would send me flowers on my release date, and I’d go on a national book signing tour.

Yes, I really thought like this: I might not have much, but like Cinderella, if I only worked hard enough, eventually my fairy godmother (literary agent) would reward me.

Yes, I really thought like this: I might not have much, but like Cinderella, if I only worked hard enough, eventually my fairy godmother (literary agent) would reward me.None of that has happened or likely ever will. After more than two decades of researching, writing, and revising my Lazare Family Saga project, I spent four years seeking traditional publication for the first book in the series, Necessary Sins. I researched how to query literary agents and which agents were the best fit for my work. I wrote and rewrote my query letter, sent query after query, and pitched to literary agents in person at writing conferences. I’m an introvert, so the latter was particularly terrifying. In all, I approached well over 100 agents. Some editors at publishing houses allow you to query them directly. When my agent well ran dry, I tried that too, submitting to about 15 editors.

I got a few nibbles. My biggest excitement was the enthusiasm of an agent at Writers House, who called my work “masterful.” She imagined she could sell it as a hardcover original. (That’s a big deal and was part of my dream.) She requested a “partial,” the opening chapters of Necessary Sins. The agent then requested the full manuscript, which she received while she was attending a music festival. She related how she frantically searched for WiFi so she could download the rest of my novel and find out what happened next. We had long conversations over the phone.

But neither this interaction nor any other led to a contract. The most frustrating thing about querying is that authors rarely get a why. More than half of the agents and editors I queried didn’t bother to respond, which is typical in the publishing business. Most of the others sent form rejections, the same canned response they send to other hopeful writers, whether those writers followed all their guidelines and were querying a project in the agent/editor’s preferred genre or whether the writer sent gobbledygook. “Not right for our list,” etc. etc. ad infinitum.

Knock till your knuckles are bloody. The gatekeepers aren’t listening.

Knock till your knuckles are bloody. The gatekeepers aren’t listening.By pitching in person and speaking to other querying writers in my genre, eventually I was able to cobble together a why, which came down to: “Your work is risky. Agents and editors are afraid of risk; they want an easy sell. You are a knee-jerk rejection.” Why is my work risky?

The agents and editors who claim they’re seeking historical fiction really want women’s fiction in a historical setting. Preferably a 20th century setting. In other words, a female protagonist, and she’d better be ahead of her time to make her “relatable.” My protagonist in Necessary Sins is—gasp—a man, and he’s very much a 19th-century man. (Read this blog post to understand my why.) The Publishing Industry knows most readers are women, and it thinks women want to read about women. So the moment an agent/editor/their assistant realized my main character was a man, they rejected my novel. My work is “too long.” Necessary Sins is about 140,000 words, which works out to nearly 500 pages in a paperback. This isn’t really that long, considering I was inspired by epic historical fiction / family sagas from the 1970s and 1980s that are nearly twice that length. But the 21st century is the age of Twitter. The Publishing Industry has decided that readers have short attention spans. They want debut novels of about 80,000 words. Shorter is even better! Longer books cost more to print, so if they fail, the publisher has lost more money. Unless you know someone in publishing and/or you’re a man (preferably both), publishers don’t care if your novel is a meticulously edited masterpiece that really needs to be longer than average. The moment an agent/editor/their assistant realized my book was over 100,000 words (the absolute limit), they rejected my novel.My work is not “own voices.” Many of my point-of-view characters are people of color and I am white. It doesn’t matter how many years of research I’ve done or how nuanced my characters are. It doesn’t matter that the Lazares’ ancestry is mostly white and they are so light-skinned they can “pass.” This is the reason that Writers House agent finally rejected me; I am a marketing problem. At this point, agents/editors/assistants probably reject all queries with characters of color in which the author doesn’t declare her/himself to be “own voices.” Even if I made it past the first two hurdles, this one is insurmountable—at least for an unknown debut author with no connections in publishing.

So after more than two decades of dreaming and labor, after more than three years of pleading at the pearly gates of publishing, I finally had to admit that my work wouldn’t be traditionally published any time in the foreseeable future.

Anna Lea Merritt’s “Love Locked Out” (1890)

Anna Lea Merritt’s “Love Locked Out” (1890)Now for most writers, this would be a temporary setback. They would have another completed project or at least another story idea. This other novel would be more marketable. Then maybe down the line, once they’d acquired an agent and publisher and proved themselves via the success of the other project, the author’s agent might potentially accept the risky project later on.

But I don’t have any other novels. The Lazare Family Saga is my passion project, my labor of love. I have sacrificed everything else in my life for two and a half decades to complete this story. I don’t have the time, energy, or money to do that again, and no other characters are demanding my attention the way the Lazares did. I have a full-time job and health issues. I can’t wait around for a bolt of lightning that may never strike.

If I’d queried for another couple of decades, there is a teeny, tiny chance an agent would have thought my work worth the risks. But then she’d have to find an editor who agreed with her. And that editor would have to convince her publishing house. I have a better chance of being struck by lightning. And the more I learned about traditional publishing, the less keen I was to offer it my soul—and my writing is my soul. This may be partly sour grapes, I admit. But I have heard so many horror stories. There are no fairy godmothers in publishing, but there are a lot of mercenaries who don’t care a fig about authors.

Maya Angelou wrote: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” For me, the agony of an unpublished story is even greater. You’ve done all the work. You’ve forged a completed novel you’re proud of. You believe it’s an important novel, and the people who read it praise it—but that handful of people are the only ones who’ll ever know your novel exists.

Unless you stop clinging to those pearly gates and find another way. Unless you go indie. That is why.

My arms are tired, but I’ll get there!

My arms are tired, but I’ll get there!

January 9, 2020

Book 1 is FREE for Book 2’s Release

Just a quick note to announce that Book 2 of the Lazare Family Saga, the highly anticipated Lost Saints, is now available as a paperback and a Kindle ebook. Here’s more info: https://elizabethbellauthor.com/book/lost-saints/

To celebrate, I’m making Book 1 of the series, Necessary Sins, FREE for Kindle for five days only, Thursday, January 9 through Monday, January 13. Ten years of my life and almost 500 pages absolutely free! This may never happen again!

On January 14, the price for the Kindle edition will go back up to $4.99. If you haven’t grabbed Necessary Sins yet, now’s your chance. If you’ve already bought it, tell a friend who enjoys historical fiction, family sagas, stories set in the antebellum American South, or tales of forbidden love!

https://getbook.at/NecessarySins

https://getbook.at/NecessarySins

December 3, 2019

What’s a Claire-Voie?

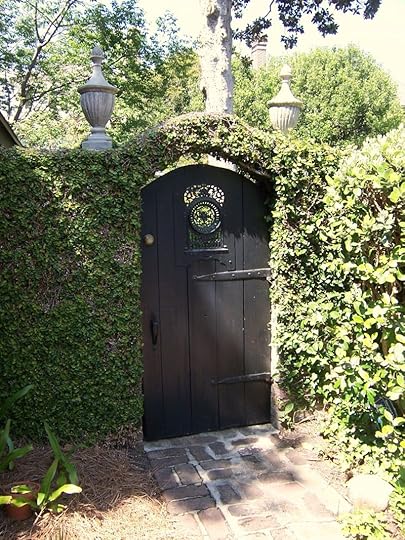

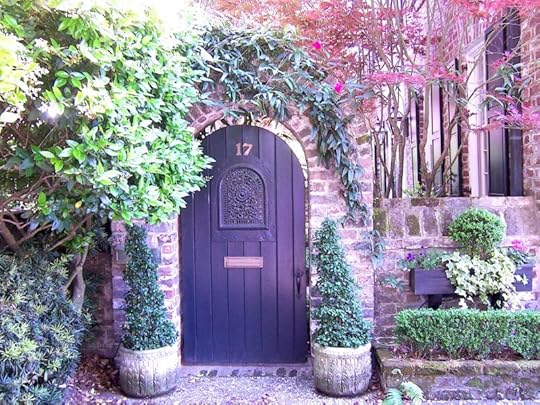

On the spine and back cover of my paperbacks and on the title page of all my novels, you’ll see my logo above the words “Claire-Voie Books.” What’s a claire-voie, you ask? It’s a gardening term borrowed from French that originated in the 17th century. A claire-voie (pronounced klair-vwah) is a window or opening that either looks onto a garden from outside it or that allows a person in one garden “room” to look into another part of the garden.

A claire-voie often features wrought iron openwork. I first came across the term in a blog post about Charleston, South Carolina, where the majority of my fiction takes place. Here are two examples of claire-voies in Charleston, windows onto private gardens (my own pics).

Claire-voie on Lamboll Street

Claire-voie on Lamboll Street Claire-voie on Meeting Street, next to the Branford-Horry House

Claire-voie on Meeting Street, next to the Branford-Horry HouseMy character Tessa has a claire-voie that is set into the garden door of her Church Street house, half-hidden by climbing roses. This opening allows someone walking down Longitude Lane, say a lovelorn priest named Joseph, to peer into her garden. Tessa’s claire-voie was inspired by these real-life garden doors on Longitude Lane in Charleston:

Joseph and Tessa, two of my central characters in Necessary Sins and Lost Saints, are both gardeners. It’s how they initially bond. Tessa’s garden door with its claire-voie is important to their relationship, and it will be important to her daughter as well. Joseph has French ancestry, so he knows the term. If you’re paying attention in Chapter 38 of Necessary Sins, you’ll discover that claire-voie also has a more risqué symbolism. Nobody does unconscious double entendres like a repressed Victorian priest.

I’ve been a Francophile for as long as I can remember; I took seven years of the language and lived in Aix-en-Provence for a semester. Literally, claire-voie translates from the French as “clear-way.” (Claire needs an e because voie is feminine.)

If claire-voie reminds you of “clairvoyant” (clear-sighted) that’s because the two terms have similar linguistic roots. I named my imprint Claire-Voie Books in order to evoke both. I designed my logo to symbolize Tessa’s claire-voie, among other meanings.

A claire-voie symbolizes my work as a writer as well. In my most recent newsletter (November 2019), I talked about my creative process and how I’ve felt my stories already existed in some nebulous other world. In order to tell them, I’m peering through a claire-voie into that other world and taking notes. I also talked about the spiritual dimension of my writing, how I hear my characters’ voices. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “clairvoyance” as “a supposed faculty attributed to certain persons, or to persons under certain mesmeric conditions, consisting in the mental perception of objects at a distance or concealed from sight.” The Encyclopedia Britannica defines clairvoyance as “knowledge…not obtained by ordinary channels of perceiving or reasoning.” When I’m “in the zone” and writing, when my characters are speaking to me, I do feel like I’m in a trance, as if I’m seeing things with my “mind’s eye.”

In addition to “clear,” the French word “clair” also means “light,” as in Debussy’s beautiful piece of music “Clair de Lune” (Moonlight). Claire-voie has a second meaning in French: a clerestory, the upper windows in a large church or cathedral that let in more light. Since most of my characters are Catholic and Joseph is a priest, this meaning is also appropriate to my work.

Nave of the Church of Saint-Aignan, Chartres, France, showing the clerestory (upper windows) by Poulpy on Wikimedia Commons

Nave of the Church of Saint-Aignan, Chartres, France, showing the clerestory (upper windows) by Poulpy on Wikimedia CommonsI’d like to think that in my historical fiction, I’m shedding light on truths that are too often concealed. As to why I needed my own imprint to tell these stories, that’s a tale for another blog post!

October 27, 2019

What’s That Symbol?

You may have wondered about the ornate, round design I use as an avatar. It’s a logo I created to symbolize my historical fiction series, the Lazare Family Saga.

I was able to pack a great number of meanings into this design, significance both complementary and conflicting. Paradoxes are at the heart of my work; rather than either/or, I choose and. To quote Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (1892):

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

The shape was originally inspired by the historic wrought iron of Charleston, South Carolina, the setting for much of my saga. Here are just three examples of Charleston ironwork, limited to circular designs, my own photos from a research trip in April 2018.

Joseph Manigault House

Joseph Manigault House

Market Hall

Market Hall

Private home on King Street

Private home on King StreetWith the help of a designer on Fiverr (a lengthy, frustrating, but ultimately successful endeavor) I created my own pattern by combining elements from two particular wrought iron gates in Charleston.

One gate stands on the campus of the College of Charleston at the 1846 Knox-Lesesne House (14 Green Way). I love this gate so much, I bought a necklace based on the pattern from .

I wore this necklace while I wrote much of the Lazare Family Saga’s penultimate draft. During my 2018 research trip, I was able to view the Knox-Lesesne gate in person, but it was obscured by a poster.

The other Charleston gate that inspired me is located at a private home on the Battery (the area near the sea wall). I first discovered this gate on Pinterest. Here’s a beautiful shot of it on Alamy Stock Photo. When I visited, it was obscured by a sign but enhanced by a friendly canine.

Within their circular designs, these two gates contain “hearts and flowers,” symbolizing both the romance and the gardens in my work. But there’s a lot of additional symbolism to unpack.

The four-petalled central flower represents Charleston’s rich botanic history and the fact that two of my central characters, Joseph and Tessa, are gardeners. Throughout my saga, but especially with these two characters, I use the Victorian Language of Flowers (a subject for another post).

Those could be the four showy bracts of a dogwood, a Southern favorite with special significance for Tessa. You’ll have to read Necessary Sins to find out why.

September 19, 2019

The Importance of Warts

My fellow historical novelist M. K. Tod invited me to write a guest post on her excellent blog A Writer of History. From Colonial Williamsburg to historical novelists, I argue that those interpreting the past should strive for authenticity, even—especially—when it’s not pretty. Or as I like to call it, The Importance of Warts. Read my post here.

You’ll find a clickable list of all my guest posts and interviews here. That page is also linked to the bottom of my About Me page.

June 17, 2019

What’s Your Genre?

Upmarket. Historical fiction. Family Saga. Mainstream fiction with a central romance. All these terms describe my work, which doesn’t fit neatly into a single category. I see this as a strength. Love beautiful writing tackling profound subjects? You’ll find it in my novels. Love history? I’ll wow you with my research. Love epics about multiple generations set in multiple locales? I’ll sweep you away. Love love stories? I’ve got you covered. My first two blurbers (published novelists who’ve read and endorsed my work) called it a drama, which is equally spot-on.

What my novels aren’t: Christian/inspirational fiction. Many of my characters are Catholics, and one is a Catholic priest. I explore theological questions because they impact my characters’ lives. But I am very critical of traditional Catholicism, and I try to show the harm fundamentalism can do. At the same time, my work is not a polemic against organized religion. I find the “bells and smells” of Catholicism fascinating and often beautiful. I try to be respectful of the Church’s good points.

Neither are my novels romances in the modern genre sense. While finding and accepting love is central to my work, while my couples experience intense joy together, not all of these couples get happy endings. I prefer love stories that are suspenseful and realistic, and I find tragedy cathartic. I think the heartbreak makes the happiness more satisfying.

My original inspirations for the Lazare Family Saga were doorstopper epics later made into television miniseries: Alex Haley’s Roots (1976), Colleen McCullough’s The Thorn Birds (1977), and John Jakes’s North and South trilogy (1982-1987). Also influential were Anne Rice’s The Feast of All Saints (1979), Lucia St. Clair Robson’s Ride the Wind (1982), Janice Woods Windle’s True Women (1994), and Clancy Carlile’s Children of the Dust (1995).

More recent historical epics with romantic elements include Sara Donati’s Wilderness series (1998-2009) and her follow-ups The Gilded Hour (2015) and Where the Light Enters (2019); Paullina Simons’s Bronze Horseman trilogy (2000-2005); and Jennifer Donnelly’s Tea Rose trilogy (2002-2008).

I love the scale of a classic multigenerational family saga, and I am awed by novels that tackle centuries instead of decades, like the work of James Michener and Edward Rutherfurd. These epics are a fantastic way to learn history and travel vicariously. However, because these authors have so much ground to cover, their characters are usually static. These characters witness dramatic events, but they rarely grow as individuals. Their internal conflict only skims the surface.

Much as I adore the sweep of history and external conflict, I also find internal conflict delicious. I wanted to have my cake and eat it too. I wanted to dig deep and really unpack the psychology and sociology of racism and Catholicism. I didn’t simply want to show Racists Being Racist and Zealots Being Zealots. I wanted to explore the implications of growing up in a racist society and a fundamentalist home on a person’s decisions and sense of self-worth. I wanted to write about flawed, struggling people like me. But I didn’t want to sacrifice the satisfying way one generation impacts and recalls another in a family saga. I also wanted to write about the American South and the American West.

I wanted to choose “all of the above” and find the surprising connections between them. How is being a priest like being a slave? How is being deaf like being a person of color? How is the spirituality of a Cheyenne Indian like Catholicism? Juxtaposition and duality are at the heart of my fiction. As one of my first readers put it, my work has layers. It’s not either/or. It’s and.

June 16, 2019

My Pen Name

I was born Jennifer Becker, but I have never felt like a Jennifer. In another context, it would have been a lovely name. After all, Jennifer is a form of Guinevere. But in my generation, there were Jennifers everywhere. In high school, I had an advanced-level French class with five students in it—and three of us were Jennifers! I got tired of turning my head every time someone said “Jennifer” or “Jenny.” They usually weren’t talking about me. I was an individual. I wanted a unique name that reflected that.

So when I was fourteen years old, I started going by my pen name, which at the time was Elyse. (It’s pronounced EH-LEES, not EL-SEE, thank you.) For most people, using a pen name is about anonymity, so this choice may seem counter-intuitive. But for me, using a pen name is about expressing my true self.

I still go by Elyse in my daily life, though I later revised my pen name to Elizabeth Bell. Elyse is a diminutive of Elizabeth, and I decided the original sounded more dignified. Unlike Elyse, Elizabeth Bell is easy to pronounce and spell, which are important in the publishing world.

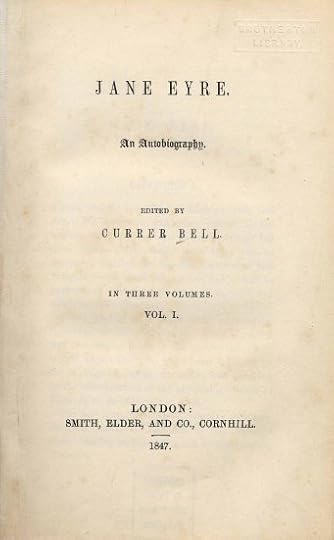

I’ve always been an Anglophile and in love with 19th-century literature in particular. The name Elizabeth honors the Victorian romantic poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, whose work I use in a few epigraphs. The name also recalls Elizabeth Bennet, Jane Austen’s heroine in Pride and Prejudice. Bell was the pen name used by the Brontë sisters and was also the maternal surname of Charlotte’s eventual husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls. If I had to choose a single favorite novel, it would be Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

I suppose I am hoping a little of that Elizabeth/Bell goodness will rub off on me.

1847 title page of Jane Eyre, written under Charlotte Brontë’s pen name Currer Bell, although she cleverly calls herself the “editor” here and the novel an autobiography.

1847 title page of Jane Eyre, written under Charlotte Brontë’s pen name Currer Bell, although she cleverly calls herself the “editor” here and the novel an autobiography.Image uploaded from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jane_Eyre_title_page.jpg

In the public domain.