Ian Josh Yates's Blog, page 2

November 6, 2019

Inventing Japan: Ian Buruma

Inventing Japan: 1853 - 1964

Ian Buruma

194pp

This is first and foremost and maybe above all else, a small book.

I was struck by two things mainly as I quickly polished off this helpful work by Ian Buruma: First, that his writing is very pleasant and almost always to the point and missing any pomposity that might ruin such a work (which is obviously meant as an overview for beginners), and second, at how big and small history can be.

Last year I spent a good amount of time reading Shiba Ryotaro's work, and as I finished the first chapter of about 20 pages here, I was stuck that Shiba had, in my quick estimation, possibly written for publication, 2000 or more pages about the same things.

While Shiba dug in deep and made a story a story of everything, Buruma is glancing over things. Both have there place on the bookshelf, and I must admit, while Shiba's work holds great importance, sometimes I need a bit of what Buruma has given us, just to inspire me to pick up a book (which, if you look at the length of time since my last review, it might be a hint of both writer's block of sorts, but more so, a lack of inspiration to just sit down and pick up a book).

So, with all that out of the way, it's time to examine Buruma's book for what it is, that being a short snapshot of about one hundred and ten years of a country being built, falling (in many many ways) and beginning to come back.

Again, if you are not very acquainted with this history, this book can act as a very suitable and quick entry into understanding what happened after Japan was forcefully made to pry open the gates to their country.

The author himself

The author himselfBuruma shows off his ability to write concisely, interestingly, sometimes forebodingly, and with just enough info to not be too little. The goal here is not to expand on everything, but to tell the simple story of how Japan changed, then changed, then changed again... and with hints of it becoming the ever unchanging country it can sometimes feel like today.

Buruma also tackles the issues that can at times be controversial within Japan. He shows no fear of suggesting that the emperor may have gotten off very easy, that Manchuria is something shameful, not only to occur, but to deny, and that organized rape occurred. He doesn't go further, never gets on a soapbox, but he doesn't back away from these issues that are often easier to ignore when living in Tokyo.

If there was any detractor from this book, it was the amount of names that started to pop up especially after the war. It's hard to complain that a history book talked about important people, but one of this size might have been even more graspable if it has chosen to speak a bit more about political groups rather than each person that came and went within these groups. Maybe a longer book is where such minutia can be brought up.

However, that is a small part at the end of a very lovely little chunk of history that has been presented to us all in a well written, smooth flowing, tight little package.

Recommended for anyone with an interest in the times, who isn't interested in anything thicker.

Published on November 06, 2019 17:00

June 8, 2019

Walking the Kiso Road: William Scott Wilson

Walking the Kiso RoadWilliam Scott Wilson288pp

Just a short review of a book I read a few years back that I just heard the author speak about. (Books On Asia Podcast)

This was written by a master translator, William Scott Wilson, and is one of his few originally written efforts I believe. We have here the story of a man in Japan who walks the old Kiso road, a piece of the old road from Tokyo, through some of the Japan alps, stopping at old Ryokan Inns and trying to touch a bit of history along the way.

I enjoyed it, I'd also say that it is reminiscent of Allan Booth, a writer who didn't write enough, so, for many people this will be a welcome walk. However, there are a bit too many asides for me (there must have been over 100 quotes in the 288pp work). In a sense I think Wilson was dong his best to stuff all the things he had read in Japanese (obviously dozens of accounts) into this singular English work.

I'll probably give some of his history translations a try (lots of samurai goodness), and would call this good enough, especially being that it is the only source for this depth of English info in the topic.

Published on June 08, 2019 04:16

June 5, 2019

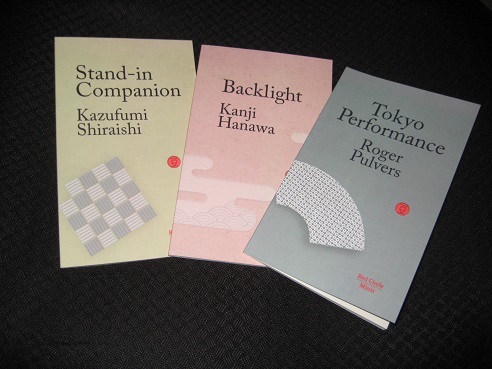

Tokyo Performance: Roger Pulvers

Tokyo Performance

Roger Pulvers

32pp

With a storyof such brevity, as is the case with the relatively short Tokyo Performance, word choice becomes all the more important. And with Tokyo Performance (the newest release of Red Circle Minis) Roger Pulvers wastes not a single world and creates a quick engaging likable take that in its limited space makes you feel that you understand five characters more deeply than in many full length books.

The story, on the surface at least, is of Nori from the famous Nori's Kitchen, the beloved (by women of a certain age anyhow) TV cooking show.

We quickly learn of Nori's life, family and mistakes, and many ways, and Nori is simply unable to bite his tongue and stop mentioning all of his embarassments, including being completely abandoned by his wife and children.

Well, when the phone lines open up, guess who the first caller is?

Suffice it to say, this is not Noris best day, though it might be his most important one.

Pulvers is able to say just as much with what he tells us about Nori as what he doesn't say. It is this ability above any other that makes him a perfect author to feature with this series.

So, overall, we have here an insightful short read that holds surprising weight and depth for such a "mini" package.

Highly Recommended

Amazon USA

Amazon USA

Published on June 05, 2019 19:05

May 31, 2019

People Who Eat Darkness: Richard Lloyd Parry

People Who Eat Darkness

Richard Lloyd Parry

454pp

"Japan's a safe country"

"Women can walk around in the middle of the night and not worry"

These are common enough stereotypes that you might even hear from an ex-pat that has spent a number of years living in Japan, and they holds some truth. I might have even said something like it myself before.

But darkness can be found even in the land of the rising sun.

Richard Lloyd Parry knows it too, maybe as well as anyone, after working the Tokyo beat as a journalist starting in 1995. Parry had as close a view of the crimes surrounding the disappearance of Lucie Blackman and the insane, unbelievable if it hadn't been true, investigation and trial that followed it.

For anyone unfamiliar with the case, a bit of background (I'll avoid major spoilers, but the book itself is far more than just the details anyway), Lucie Blackman was a young English woman who went missing while living and working in Tokyo in the year 2000. This led to the revelation to her family that in actuality, Lucie had been working at a hostess club, far from the type of work her parents had pictured.

Now, hostesses are not sex workers, but the work is certainly the selling of a sexual image in the very least, as it almost always involves selling your time outside the clubs to date and spend time with important customers.

When it became apparent that something very odd was happening, some of Lucy's family rushed to Tokyo in an attempt to pressure the police to do more and this begins the story that will lead to battles between the Blackman's and the Japanese Police, the narrowing down of a suspect, and the eventual, though delayed, finding of a young woman's body.

Simple cut and dry case?

Not at all.

A life too short.

A life too short.There are so many twists and turns along the way that I'm not sure I could be trusted to even attempt to list them all, and all that detail gives us a heavy book, but, if I haven't hinted enough already, one that a reader will not want to skip a single page of, or put down for any longer than it takes to get enough sleep.

Parry shows his ability to take a jumble of information and put it all down in the best way for a reader to feel that they haven't missed anything, but haven't been bogged down either. The writing is fluid, intelligent, and always intriguing. Parry leads us on an incredible walk, one in which we often want to close our eyes, but always take peeks between the slits of our fingers to catch a glimpse of the monster.

And what a monster it is... but I did promise not to spoil anything, didn't I.

Suffice it to say that Parry found in Kanto a character in Joji Obara that belongs in the works of Thomas Harris.

However, maybe the most incredible part of this book, is that the darkness eater and his horrible crimes don't become the soul focus. Instead, two more amazing stories emerge.

Parry spends a large part of the book humanizing Lucy's father, who might have instead been easily tossed aside as a 2D minor villain or a simple schmuck. While the news at the time seemed to have decided that Tim Blackman was not the grieving father he ought to have been, Parry doesn't leave it at that, and spends time filling any the blanks and painting the picture that was glossed over too often in initial coverage.

Finally, along with all of that, Parry is able to wind in the story of the Tokyo police. Are the misunderstood by the foreign media? Highly Inept? Or playing a game that only they know the rules to? Along with all the other wonderful parts expounded upon above to recommend this book, anyone interested in the case of Carlos Ghosn might find this work an amazing insight into the workings of Japanese police investigation and the criminal process as well.

This is an incredible book and Parry a worthy journalist and author. In his later work, Ghosts of the Tsunami, Parry took the deaths of thousands and found the small story within all those stories. Here, with just one young lady's death, (Oh, but maybe not) Parry shows finds the big story.

A masterpiece of true crime writing.

One of the only photos of Joji Obara

One of the only photos of Joji Obara

Published on May 31, 2019 02:06

May 26, 2019

Tokyo Ueno Station: Yu Miri

Tokyo Ueno Station

Yu Miri

Morgan Giles (Translator)

180pp

Light does not illuminate. It only looks for things to illuminate. And I had never been found by the light. I would always be in darkness.

Tokyo Ueno Station, by Yu Miri and translated by Morgan Giles is simply stuffed full of the type of insightful quips as above. Though dark in focus, it doesn't push away a reader, but pulls them in with the vision of one man's journey.

Kazu, our main character has lived a life of struggle and loss. He has lost love, money and children. Though only his son has died, and his daughter remains, it seems as though the shame of being seen as a parasite has made her just as lost to him.

My children held little affection for me, the father they rarely saw. And I never knew how to talk to them either... we shared the same blood but I meant no more to them than a stranger.

Miri, with her work here, is giving a voice to the homeless, but not just the homeless, as the above quote should show, she doesn't see the homeless alone in a box, but as part of an extension, or continuation of some of the more problematic parts of Japanese society: Fathers with little connection to children as one example.

To be homeless is to be ignored when people walk past, while still being in full view of everyone.

However, it is the homeless issue that takes up much of this book, and in what may be a gutsy move, much of our man Kazu's life is put in comparison with the Heisei Emperors. They were both born in the same year, son's born on the same day even. They both also find themselves in the park that sits in from of Ueno station, the park given to the people by a former emperor, yet taken away by the police when cleanup is necessary to protect the image of the emperor and Japan.

It seems that Yu Miri has found herself under attack from time to time from some right wing activists of sorts. That is a shame, as this book is certainly not an attack on Japan, or the emperors. It is obviously a call out for the respect of all humans, or all Japanese, to be treated as humans. It is not a condemnation of the emperor, but of the system that allows people to slip down and then kicks them when they are there.

Overall, it is a beautiful and worthwhile read. It portrays a situation, a life, that is undeniably touching, and undeniably true. Though, maybe we don't want to look, and pretend not to see sometimes.

Highly recommended.

Yu Miri

Yu Miri

Published on May 26, 2019 18:42

May 3, 2019

In Memory of Howard Hibbit

Howard Hibbit: June 27, 1920 - March 13, 2019

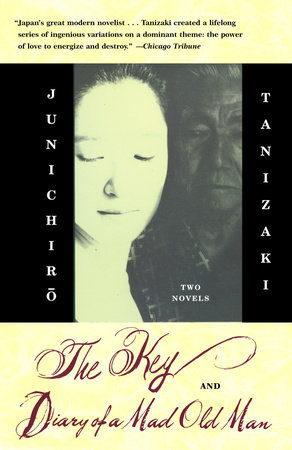

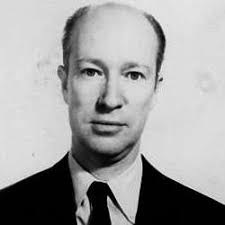

I was sharing some of my works throughout Golden Week and it was brought to my attention by @therealcornjob on twitter that one of Tanizaki's main translator's, Prof Howard Hibbit, had just recently passed away at the amazing age of 98.

I have enjoyed numerous chances to speak with and interview translators over the last few years, and it is something I find wonderful and enlightening. I won't get the chance to speak to Dr. Hibbit, so instead, I'll give my thanks, a small bio, and my thoughts on the works I've read.

Harvard educated, from undergrad to doctorate, with a small break to work as a language specialist during the war. Hibbit then went on to work at UCLA before returning to teach at Harvard.

Some of his major translations (Wiki) include:

The Key by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1961Seven Japanese Tales by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1963 Diary of a Mad Old Man by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1965 Review Harp of Burma by Michio Takeyama, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Rutland (Vt.) 1966 Beauty and sadness by Yasunari Kawabata, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1975 Quicksand by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1994 Review

I have read The Diary of a Mad Old Man and The Key, and both are exceptional works of odd erotic aging. Maybe that seems like an odd description, but I assure you, it's spot on, and if it intrigues you give them a look... and if it makes you cringe, maybe avoid them (at your loss).

I also have Quicksand as well as Beauty and Sadness on my shelf and hope to read them very soon.

As a pioneer in early J-lit translations I think anyone who enjoys this blog will join me in thanking Dr. Hibbit and saying how happy it is to see such a man enjoy a good long life.

I encourage everyone to pick up one of his books whenever you get a chance, and comment below on on my twitter @fulltimerinjp.

RIP

Professor Howard Hibbit

Professor Howard Hibbit Can you name them all? A murderers row of the J-lit/translators community.

Can you name them all? A murderers row of the J-lit/translators community.

Published on May 03, 2019 17:23

May 2, 2019

Osaka Museum of Housing and Living

Osaka Museum of Housing and Living

My family and I got the chance to check out the Osaka Museum of Housing and Living today, and I though it was a really neat chance to check out what 1830's Osaka looked like.

I especially loved the walk through neighborhood with controllable weather and indoor Tenjin Matsuri.

Right at the top of the Tenjinbashi shopping street, this is a fun couple of hours, especially if the weather isn't perfect... at least outside.

Check out my pics below:

The Entrance:

The Entrance:

I want one under my stairs

I want one under my stairs

Float from the Tenjin Festival

Float from the Tenjin Festival

A sketch of old Osaka.

A sketch of old Osaka.

My family and I got the chance to check out the Osaka Museum of Housing and Living today, and I though it was a really neat chance to check out what 1830's Osaka looked like.

I especially loved the walk through neighborhood with controllable weather and indoor Tenjin Matsuri.

Right at the top of the Tenjinbashi shopping street, this is a fun couple of hours, especially if the weather isn't perfect... at least outside.

Check out my pics below:

The Entrance:

The Entrance:

I want one under my stairs

I want one under my stairs

Float from the Tenjin Festival

Float from the Tenjin Festival

A sketch of old Osaka.

A sketch of old Osaka.

Published on May 02, 2019 05:27

April 29, 2019

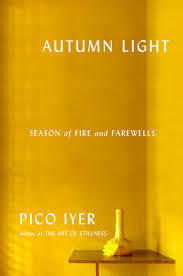

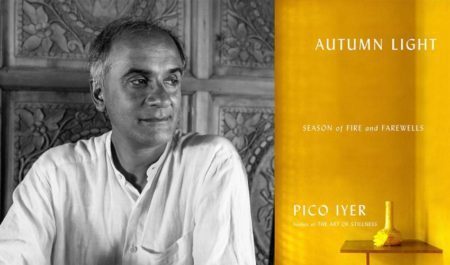

Autumn Light: Pico Iyer

Autumn LightPico Iyer246pp

A bit of controversy surrounded Pico Iyer's newest work, or at least surrounded the New York Times review of his latest work.

A bit of controversy surrounded Pico Iyer's newest work, or at least surrounded the New York Times review of his latest work.In the review Iyer was supposed to have suggested that he had chosen to never learn Japanese because it lent to the mystery of the life he led. It added to his never settling anywhere in the world, never sprouting roots, never belonging.

Many the twitter maniac (me too?? to a much quieter degree I shared my distaste for such ideas) lambasted Iyer and his ignorance.

Well, I'll start this review with a quote of Iyer speaking with his step-daughter that at least tells Iyer's true feeling:

"Sometimes" I tell Sachi, "when I come back from the ping-pong club, through the neighborhood, I can smell cooking from every other house. Which is the smell of family, of home. Even if it's not a home that can ever officially be mine."

"Is that the reason you don't learn more Japanese"

"Not exactly. That's just laziness.So, at least in my book, Iyer can be forgiven his misdeeds, as the only suggestion I disliked from the NYT article was that he had somehow purposefully decided to avoid learning Japanese. Being lazy, is at least understandable, and at least taking the blame for his own circumstances... so, that being settled, I can attempt to look at this with purely fresh and open eyes... mostly, since this is basically the sequel to a book that I found beautiful and troubling.

And so, well, let me focus on all the positives before I find myself getting into the gossip of my old friends, the characters of these two books.

Again, and as always with Iyer, this is a wonderfully moving and insightful book. The prose are often nearly poetry, and Iyer's gaze sees those things that we all see, but maybe deeper, and his words continue past where our own stutter and stop.

Describing the beauty of seasons (the split main theme of this work, along with the theme of death), Iyer writes:

Cherry blossoms, pretty and frothy as schoolgirls' giggles, are the face the country likes to present to the world, all pink and white eroticism; but it's the reddening of the maple leaves under a blaze of ceramic-blue skies that is the place's secret heart

Pretty, that description. Insightful, quite possibly, but just as much into Iyer and the preferences of those reaching the age of 60 for autumn over spring and for subtle over bright.

The work is full of such quips, and anyone looking to love Japan a little more than they already do will find a million little lines to give them what they want.

Additionally, anyone with death on their mind will find a million tiny little pokes into that beast. Iyer is watching his mother and mother-in-law come closer and closer to leaving this realm, and he is struggling with finding meaning within the losses that have and will come.

Those are the reasons to read this book. They are there, they are throughout and they will satisfy many.

However, overall, I didn't love this book and would say I didn't like about as much of it as I did like, which should explain my giving it a middling 3/5 on my GR score.

What didn't I like... (stop here if you want to read this book, or not think I obsess too much)

First, Iyer has never, in the 28 years or so since his first book about his wife, been able to get past his split personality in relation to Japan.

For Iyer, Japan is an amazing land of mystery and gorgeousness that has really found so many answers to the problems that the west cannot solve.

However, at the very same time it is a land of rigid rules and awful weights stacked up upon the people, that are destroying them, and that he must save them from (or at the very least, save his wife from).

Can both of these be true? Sure. Japan is not a single thing. But, what is infuriating in reading Iyer regarding this is that he is so sure that everything in front of him is an example of the prior, while the former are the powers unseen. Do they ever appear? Yes, but just to disagree with Iyer and then disappear again for the beauty to shine.

If that all feels cryptic, allow me to expand.

The Lady and the Monk was the "fictional" story of a man who moved to Kyoto, fell into love with a married woman with two children and then... well, it ended there.

In real life, Iyer married his Hiroko, and the children were taken away from their father. Was that to his dismay? It's never spoken about in that work or this new one. Surely that's private, but it's that kind of unspoken undertone that paints a slightly unflattering picture of Iyer, at least as he is as a character within these books.

One of the revelations of this new book is that Iyer admits that the children never saw their father again, and that the divorce led to Hiroko having massive difficulties with her mother, and that her brother completely cut off all contact with the family (ah... the monster of Japan shows itself again, only to disappear and just be mentioned like gossip, whispered late at night).

Who chose, husband or wife, to not meet the children? I don't know, and it's not in the book, so it's not my business... though it would have been so terribly interesting.

Is Iyer to blame for the rigid beliefs of the brother and mother? No, that was Hiroko's issue to deal with, and she doesn't ever make much progress.

And then there is the character of Hiroko. (I'll skip past the fact that she is written as if she learnt to speak from Yoda).

Numerous times Hiroko is spoken of as if a renegade martyr, such as:

Hiroko, a pioneer in remaking her life by walking out of a marriage that was wrong for her

or

like his sister, like his father, Masahiro (the brother) was never going to fit into a society in which to be as bland and invisible as a grain of rice, at least on the surface, was the price of admissionor

But Japanese women still have no good place in the system, so either they defect - as Hiroko had done by marrying me - or they try to make the most of the free time that being denied most public opportunity can bringHiroko is not to ever be considered a woman who chose to marry an interesting foreigner at the loss of her ex-husband, her brother (by his own doing) her mother and father (more on that later) and likely her children...

Iyer, for all his time in and love of Japan, writes the great American explanation for his wife's actions. She deserves her freedom and chance at life and love, damned to all others.

But, am I reading too much into everything. The husband has disappeared and certainly didn't, in the great American father tradition, fight tooth and nail to keep contact with his ex-wife and her family. And the brother is maybe just a fool (and a loose end to this book as well, as nothing is ever resolved with him). And the mother... screw the old woman, what has she lost?? For all Iyer spouts off about the great community of Japan, this elderly Japanese lady is quickly set aside for convenience.

But, even if some people notice those oddities, I wonder how many other readers will pick up on Iyer's numerous mentions of money.

Iyer coming to Japan was basically his abandoning of a well paying New York career for a dive into the blessings of poverty. It started with Buddhist learning, but even though that was abandoned, Iyer loves to mention how small and empty his 90,000 yen a month apartment is (although in a rather spiffy Nara suburb, which Iyer provides a map to, for god-knows what reason?).

It's often mentioned that Iyer, "doesn't work", and that the neighborhood children mock him as a kind of sugar baby to his working wife. Yet, this is Pico Iyer, the writer. Certainly he provides for his family. Likely, but, maybe by choice, Hiroko is presented to not benefit from the money from Iyer's fame, in her small apartment (that she loves, as all Mari Kondo Japanese women do), constantly working and cleaning and cooking.

Hiroko once says to her mother, now stuffed into a nursing home, begging to be taken home:

"No, Grandma," says Hiroko, struggling to keep calm. "I have a job in Nara, remember? If I don't work, we can't eat. You have a new home"Hmmm... but surely Iyer could afford to let his wife stay home and help her mother... but, then that small apartment, filled already to the brim just with shadows... but, the parents house in Fushimi-Inari... it's all empty now, they could move there and save that 90,000 yen a month that's keeping Iyer from properly eating... it's closer to Kyoto, closer to a shinkansen, to getting to an airport for our writer's travels.

And then I get it. I get what is bothering me about this story and what somehow wasn't hidden better.

In the first book I felt that Iyer had written it expressly to excuse and explain that he was not at fault for his wife's divorce.

And in this one I can't help but feel that Iyer is trying to explain why his mother-in-law couldn't live together with them during her dying days.

The apartment is too small.

Hiroko is too busy working to put food on the table.

It's the older brother who bears the responsibility and he's gone and run away.

Maybe I'm crazy. But I beg any other reader of this work to take note of the way Iyer speaks of his own mother, whom he lives with and cares for much of the year. At one point he mentions:

I've taken her on four cruises in the past four years - Tallinn, Ephesus, Alaska, St. Lucia - and I bought her a shiny new car two years ago. The seasons are one of the way we remember that children become parents of their parents.

It's as if, when in America, Iyer is the well off famous writer, but when in Japan, the poor dreamer. He embraces simplicity... but not for the whole year. We all know summertime is for cruises.

But maybe it's more fair to say, that with his own mother, he is the doting asian Indian son who knows his place to care for his elders, while in Japan, he's the American or the Englishman, pulling Hiroko away from caring for her own family. Pushing her to be more American, abandon all those heavy duty duties. Come walk with me among the reddened fallen leaves. Come dream with me.

I wonder how many will get this far... I apologize for the length, but assure you I have actually avoided the half dozen quotes I highlighted that suggested that although Iyer was at home all day playing ping-pong it is his wife who did the shopping and cooking... and I have also left out the odd subplot where Hiroko's daughter is abandoned by her foreign husband/boyfriend (I was unsure) and Iyer explains it's all tragic because the boy is obviously gay.

So, a rather odd book overall, but one I found amazing depth within, though not the depth I feel that author felt he was revealing.

Comment below please if I am on to something, or am just a madman.

Published on April 29, 2019 04:58

April 20, 2019

Translator Interview: Juliet Winters Carpenter

Juliet Winters Carpenter in Interview

Recently I had the great pleasure of both reading The Great Passage (Full Review coming soon to the Writers in Kyoto site) and also meeting and asking a few questions of the translator.

For anyone who somehow doesn't know, Juliet Winters Carpenter is a name you should know if you have any interest in Japanese literature in English. Her career has been long and full, as along with teaching at Doshisha Women's College, she has translated an absurd number of books.

On a personal note, the first book I was ever hired to translate for a now defunct magazine was Mrs Carpenter's translation of Nonami Asa's The Hunter and I have always had a few books with her name on them on my bookshelves.

As for The Great Passage specifically, it is the story of a group of people coming together to create a new dictionary and of the man Majime, who is chosen to lead the group after the older generation has to call it quits. It is an enjoyable read, with a unique look at love; love for friends, love for work and love for that special someone.

JL Carpenter was wonderful enough to share her opinions on the book she brought to an English audience.

What’s the story behind you being asked to translate The Great Passage?

defJWC: I was asked to translate a sample of The Great Passage by Moriyasu-san, an editor formerly at Kodansha international who worked for JLPP and Books in Japan. Of the several samples I did of various works Passage got picked up by AmazonCrossing.

2. Was there any consideration (such as publishers nervous for English readers' reaction) to removing all the Japanese and attempting to find some kind of matching words in English? Did you feel including the Japanese examples was important/more interesting?

The whole point of the book is the love affair with the Japanese language, so I don’t see how it would have worked with English examples. I loved The Professor and the Madman, about the making of the OED, and I saw this as a book in that mold. It’s a fascinating chance to peer into another language and feel it like a native speaker. Also, the readers can think for themselves of comparable conundrums and interesting bits in the English language.

3. One young reader in our group had a bit of a reaction to what he saw as the workaholic nature of much of the book (by the way, once he finished the ending he commented that he loved the book and that the story had come around perfectly). During your wonderful career, have you ever translated something memorable, that in Japanese worked perfectly, but in English couldn’t convey the same meaning or feeling?

Things that work in Japanese but not in English. Yes of course! A small example is the story of the bamboo cutter which forms a background to Kaguya’s part of the story. That’s why her restaurant is named “the back of the moon“ for example. This would all be evident to Japanese readers but goes over the heads of most English language readers, alas. On the other hand, sometimes the translation can do things the original cannot. After Majime meets Kaguya, he is lovestruck the next day at work. His coworker says, “what are you mooning about?” The word “mooning” connects the two scenes and ties in with the night before —the magical moon – whereas the Japanese was something ordinary like ぼんやりor ぼけっと. So it works both ways.

4. If I’m not mistaken, you started translating after the film had been released and won the Japanese Academy Award for best picture. Did you watch the film before translating the book, and do you have any feeling about taking advantage of a visual example of the characters, or avoiding being influenced by the director’s interpretation?

I watched the movie and was interested by the way it introduced the characters’ love of/obsession with language. Majime has a scene where he reels off multiple meanings of kiru , cut, and the subtitles fit in perfectly. I didn’t really use anything from the movie except the title, which was a wonderful gift.

5. Please feel free to share any future projects that people might want to check out, or (if you have any) social media plugs.

Other projects:

March 2019: Heritage Culture and Business, Kyoto Style: Craftsmanship and the Creative Economy.

By Murayama Yuzo. Japan Library April 2019: 英語朗読で楽しむ日本文学: Gems of Japanese literature

By Aotani Yuko and Juliet W. Carpenter. Alc

The above contains excerpts from Genji Pillow Book and Narrow Road of the Deep North; passages by Soseki, Dazai, Akutagawa, and Edogawa Ranpo; Miyazawa Kenji’s poem “Ame ni mo makezu”; a Yosano Akiko short story; and part of Gon the Fox. Comes with CD

Other projects include Hirano Keiichiro’s “After the Matinee” due out from AmazonCrossing next year and Minae Mizumura’s “Shishosetsu from Left to Right” (as yet untitled in English) due out from Columbia University Press next year; the final volume of Ryoma ga Yuku due out from Japan Documents eventually (2020?)

Also I will translate Hamada Shoji’s 無尽蔵 and possibly a book on Tokugawa culture by Haga Toru.

Beyond that no plans except I’d love to do more Soseki and more Enchi.

A final thanks again to Juliet Winters Carpenter for her time, in answering our questions, but more so for her years of work bringing Japan to those not able to read Japanese. We look forward to your work in the future.

Published on April 20, 2019 19:36

April 9, 2019

The Little Book of Japan

The Little Book of Japan

Charlotte Anderson

Grazed Vilhar (Photography)

192pp

It's been a while since I have written a blog on a book, and I do have a few novels finished and waiting for me to think over and dig deep into, but with a new school year upon us, I need a bit of time before I feel up to that... so, here is a lighter book for the Japan lovers.

The Little Book of Japan was rereleased last year from the Tuttle publishing company and it is everything it claims to be and more. It is little, easily tucked in a bag pocket. It is Japan, with a quick 2 - 6 page look at just about any place or cultural note the beginner to Japan would want to see.

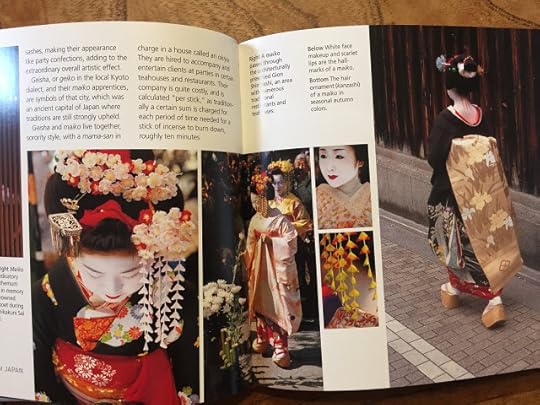

It ain't Japan without pics of these Kyoto mysterious beauties

It ain't Japan without pics of these Kyoto mysterious beautiesIt is also beautiful, inside and out. If you are unfamiliar with Tuttle, they publish on various aspects of Asian culture with various interests and focuses, but as a rule, if you pick up a Tuttle book, it will be beautifully bound, and full of breathtaking photography.

The Little Book of Kyoto and The Little Book of Tokyo were also released, and I would recommend picking up whichever one feels more close to your heart.

Not literature, but photographic beauty with a bit of a beginners class in Japan. Recommended for such beginners, or as a coffee table book for those who want to keep Japan alive in their homes, wherever they lay their heads at night in this expansive world.

A look at the beloved Bento Boxes

A look at the beloved Bento Boxes

Published on April 09, 2019 18:00