L.A. Smith's Blog, page 5

December 18, 2020

Merry Christmas to All!

I don’t know about you, but I need Christmas more than ever this year. But even that will not be the same. Normally we would enjoy two large and riotous family get-togethers. Instead, for the first time since we had children my hubby and I will celebrate Christmas with just the two of us. Current COVID restrictions here in Alberta forbid any household gatherings outside of immediate household members. Sigh. It means that our adult kids who live separa...

December 4, 2020

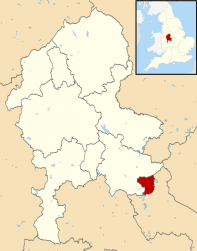

Tamworth

Close to the center of England is the large market town of Tamworth, boasting a population of approximately 77,000. It lies in the Tame Valley, and lies near the confluence of the River Tame and the River Anker.Tamworth means “enclosure by the River Tam”.

In Roman times the area was the home of the British tribe known as the Coritani. There is some evidence of Roman occupation in the area, and Watling Street, a major Roman road, runs directly next to it. The arrival of the Saxons in the late sixth century or so meant that the area came under their control, and eventually, Tamworth became the seat of the kings of Mercia.

In the seventh century, Tamworth was therefore the royal seat of Penda of Mercia, one of the most powerful kings of the Anglo-Saxon era. Although Penda was a typical king of the period, who would have spent much time visiting his noblemen of the kingdom, gathering (and distributing) tribute, and strengthening alliances, Tamworth was the place he would always return to with his family and royal retinue.

Tamworth (the red in the main map) lies in Staffordshire (the red in the smaller inset map). You can see that it is right in the centre of England.

Of course today nothing remains of those original buildings. They would have been timber as well as wattle-and-daub buildings, consisting of a great hall and other buildings such as residences, cookhouses, stables, and other necessary buildings. In the seventh century, when Penda was king, one building you would not find there is a church. That is because Penda was a pagan, and followed the old Anglo-Saxon beliefs. The church in today’s Tamworth, St. Editha, stands on the ground of the first church built there in the 8th century.

There were defensive earthwork and timber walls built around Penda’s Tamworth (possibly built on top of Roman fortifications), these defenses were strengthened in the 9th century by Aethelfled, the Lady of the Mercians, after she rebuilt the town following the destruction the Danes brought with them.

One of the most exciting Anglo-Saxon finds of recent years, the Staffordshire Hoard, was found near Tamworth, close by the ancient Roman road of Watling street. Archeological work is ongoing at the car park close to today’s Church of St. Elditha, where some interesting finds could point to some of the 7th and 8th-century buildings of Tamworth’s history.

Although today’s Tamworth is more of a sleepy town than a tourist magnet, it boasts a long and rich history, and looms large in the landscape of 7th-century England. Once pandemic restrictions are over and I can get on a plane, my delayed trip to the UK is definitely going to include a stop in Tamworth!

The post Tamworth appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

November 20, 2020

The Time Travel Challenge

Time travel is a trope often used in speculative fiction books, but it is a tricky one to handle. But done right, it can be a great deal of fun for the reader and the writer alike.

When I set out to write my historical fantasy trilogy, I knew that the main character was going to be a modern era person. Portal fantasy, where someone from our modern world is transported to a different world or time period has always been a favourite genre of mine. So I set out to write my own, but almost immediately I bumped up against how I was going to explain the time travel part of the story.

There are many ways to handle the idea of time travel in a speculative fiction book. Often how the author uses this concept will depend on the genre of book he or she is writing.

First of all, time travel often shows up in science fiction books. In these books, time travel  either has become a type of technology that people use or time travel is the result of some other type of technology, either intended or inadvertent. So, for example, H.G. Well’s The Time Machine (1895) was the first popular novel to employ this device. In that book, the Time Traveller (he has no name other than that) is an inventor who has developed a machine that will allow him to travel forward through time and the book is his recounting at a dinner party of what he experienced when he did this. In the Dr. Who TV series, the Doctor is a Time Lord and travels back and forth through time using his time ship, the TARDIS.

either has become a type of technology that people use or time travel is the result of some other type of technology, either intended or inadvertent. So, for example, H.G. Well’s The Time Machine (1895) was the first popular novel to employ this device. In that book, the Time Traveller (he has no name other than that) is an inventor who has developed a machine that will allow him to travel forward through time and the book is his recounting at a dinner party of what he experienced when he did this. In the Dr. Who TV series, the Doctor is a Time Lord and travels back and forth through time using his time ship, the TARDIS.

An example of inadvertent time travel through the use of technology is found in Star Trek, such as the episode Tomorrow is Yesterday, when the Enterprise finds itself back in the early seventies due to getting tangled up in the effects of a high-gravity “black star”. Time travel was used as a plot point in the Star Trek universe several times in many of the episodes throughout the different iterations, and it generally involved some kind of accidental travel through time. But accident or not, the explanation is always some type of scientific one.

But in fantasy books, time travel is not usually the result of a machine or technology. Generally in this case the person goes back in time due to some kind of magical power/spell/effect. Case in point would be Diana Gabaldon’s hugely popular Outlander series. In these books, Claire Randall, a young nurse from post-WW II Britain, is magically transported through a split standing stone in Scotland to the 17th century. Or, I might point to my own book, Wilding, where modern-day Thomas MacCadden is chased by strange creatures on Halloween night and suddenly wakes up to find himself in 7th-century England. In these types of books, however an explanation as to why this has happened is often eventually given. In the Outlander series, Gabaldon straddles the line between science and fantasy, allowing that this particular ability is a genetic one, and skirting along the lines of fantasy by inferring that certain gemstones and certain geographical locations are needed in order to pass through time. In my own books, Thomas quickly discovers that, unbeknownst to him, he is actually one of the Fey and has the inherent Gift of Travelling through time. Stephen Lawhead’s Bright Empires series is another fantasy time-travel series, the device of travel in it being ley lines.

But in fantasy books, time travel is not usually the result of a machine or technology. Generally in this case the person goes back in time due to some kind of magical power/spell/effect. Case in point would be Diana Gabaldon’s hugely popular Outlander series. In these books, Claire Randall, a young nurse from post-WW II Britain, is magically transported through a split standing stone in Scotland to the 17th century. Or, I might point to my own book, Wilding, where modern-day Thomas MacCadden is chased by strange creatures on Halloween night and suddenly wakes up to find himself in 7th-century England. In these types of books, however an explanation as to why this has happened is often eventually given. In the Outlander series, Gabaldon straddles the line between science and fantasy, allowing that this particular ability is a genetic one, and skirting along the lines of fantasy by inferring that certain gemstones and certain geographical locations are needed in order to pass through time. In my own books, Thomas quickly discovers that, unbeknownst to him, he is actually one of the Fey and has the inherent Gift of Travelling through time. Stephen Lawhead’s Bright Empires series is another fantasy time-travel series, the device of travel in it being ley lines.

There is also a subset of time travel books known as time slip. In these books, the protagonist is suddenly transported to a different time with no knowledge of how he or she got there, and it is never explained through the course of the book. The character is either stuck in that time period or, if they return, it is not by their volition and is not controlled by them. This is often used in children’s books but is there are certainly many time travel books for the adult market that use this device. Mark Twain’s A Conneticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court made this plot device very popular.

Aside from the mechanics of time travel, authors must also wrestle with some of the other difficulties presented by using this device in their books. The main difficulty is, if someone travels back in time, what are the implications for the future? Each author will approach this question differently. Some avoid it altogether by only allowing their characters to move forward in time, not backwards, as was the case in The Time Machine. The question then becomes how to change the future that was seen, if it is a nasty one. But if travel to the past is allowed, this question is one of the first that must be dealt with. The grandfather  paradox sums up the difficulty: if you travel back in time and kill your grandfather, what happens when you return to your time? Will you have also, in effect, killed yourself? Many books address this paradox. Some time travellers go back in time to do a certain deed, like kill Hitler, and come back to see that the unintended effects of that were far worse than what actually happened. Stephen King’s 11/22/63 is a good example of this. The main character realizes he could go back in time and stop the Kennedy assassination, and tries to do just that, with unintended consequences big and small.

paradox sums up the difficulty: if you travel back in time and kill your grandfather, what happens when you return to your time? Will you have also, in effect, killed yourself? Many books address this paradox. Some time travellers go back in time to do a certain deed, like kill Hitler, and come back to see that the unintended effects of that were far worse than what actually happened. Stephen King’s 11/22/63 is a good example of this. The main character realizes he could go back in time and stop the Kennedy assassination, and tries to do just that, with unintended consequences big and small.

11/22/63 also highlights another common question of time travel stories: is it even possible to change events in the past, even if you know about them before hand? In King’s book, the main obstacle in the protagonist’s goal is the past itself, which throws roadblock after roadblock in his way as he tries to stop Oswald, or indeed, to change smaller events in the past. Claire, in the Outlander series, bumps up against this too, and eventually concludes that big events cannot be changed (like the Battle of Culloden) but smaller events can.

Even when the characters in time travel stories do succeed in changing the past, other difficulties can arise. Often it is the creation of alternate time streams, where several possible futures arise because of the effects of the time traveller’s meddling. Or, you can get the Time Police trope, where people from the future hunt time travellers down in order to stop them from altering events. If you saw Tenet recently in the theatres, you will have seen a version of that idea. Although the film insists that it is NOT about time travel but, okaaay. (Aside: if you can explain what actually was going on in the last third of the movie, HELP ME).

Time travel books don’t necessarily have to be strictly speculative fiction, though. A stellar example of this is the stunning The Time Traveller’s Wife, by Audrey Niffenegger (the book, NOT the movie. Don’t get me started.) At the heart of it, this is a love story through and through, with the time travel element enhancing that main story.

Other fun subsets of time travel stories is the idea of a time war, with characters moving back and forth through time in order to gain supremacy over which version of history would result in their side’s supremacy. The Terminator franchise is probably the best-known example of this.

Other fun subsets of time travel stories is the idea of a time war, with characters moving back and forth through time in order to gain supremacy over which version of history would result in their side’s supremacy. The Terminator franchise is probably the best-known example of this.

Finally, time travel does not necessarily have to happen just in our own world. There are many stories where time travel occurs not just in the context of our own world, but where the characters travel through both space and time and go to other worlds as well as our own. Dr. Who is a good example of this, as is the Time Quintet series by Madeleine L’Engle. In the opening book, A Wrinkle in Time, Meg and her siblings and her friend Calvin travel through both space and time using means of a tesseract, a folding of time and space, in search of her missing father.

I love time travel books. They can explore profound questions about who we are and what might happen in the future, or shine a spotlight on events of the past and force us to wrestle with the “what ifs”. They can also just be a great deal of fun.

What’s your favourite time travel novel/movie/story? Leave your answer in the comments, I’d love to find some new favourites!

Featured image: Photo by Thomas Bormans on Unsplash

The post The Time Travel Challenge appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

November 5, 2020

Review: An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors, by Curtis Craddock

An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors (2017) is a fantasy novel set in the Risen Kingdoms, where the continents are set adrift in the skies, and whose ships must sail through the ether between them. The setting is vaguely medieval, loosely based on 17th century France and Spain, and as such the story is rife with court intrigue, looming war, and royal squabbles, added to which is the magical powers the various ruling families exhibit.

In short, this book is a great deal of fun. The main character is Isabelle des Zephyrs, a young woman disdained by her own high-born, powerful family for both her deformed hand and her lack of magical ability. But to her scheming father, the Compte des Zephyrs, she becomes useful when she reaches marriable age and so can be a pawn to be used in the game of kings between their own nation, L’Empire Céleste, and the rival nation of Aragorth, whose ruling families have a type of mirror-magic. He arranges for her marriage to the Principe Julio of Aragorth, who might become king once his sickly father dies. The marriage is also pushed by the strange half-human, half-mechanical artifex Kantelvar, a high ranking religious official who harbours many secrets of his own.

Isabelle, abandoned and forgotten by her family once they learned she did not share the Celeste shadow-magic, whereby their shadow can suck the soul or the life out of another, has grown up more or less under the tutelage and protection of Jean-Claude, the King’s Own Musketeer who was assigned as her bodyguard at her birth by the king. As such she has been somewhat free to follow her own pursuits, including the study of mathematics and the science of flying the airships, pursuits generally frowned upon for a woman. She even goes so far as to publish mathematical treatises under a male nom de plume.

Isabelle has no choice in the arranged marriage, but she determines to see it as an escape from her cruel father and a chance to make a new start in a new land. The marriage would also bring stability to the relationship between the two nations, who are at the cusp of war. She also is granted a boon by Kantelvar: if she goes to the marriage and agrees to do all she can to promote peace between the two countries, he will restore her friend Marie, who had been turned into a bloodhollowed slave by her father many years ago in an attempt to determine if Isabelle herself had the shadow-magic and would use it to protect her friend.

But complications abound, and plots and betrayals swirl around Isabelle almost as soon as she sets off to Aragorth on the sky-ship. The only one she can truly trust is her faithful Musketeer Jean-Claude, and she is going to need all of his help to untangle the web of lies and danger that tightens around her.

I really enjoyed this book. Isabelle’s growth from solitary maiden to a woman confident of herself and her place in the world is fun to watch. The relationship between her and Jean-Claude is a touching one. I’m also really glad Craddock didn’t take the easy way out and have a romantic relationship between Isabelle and Julio spark right from the beginning. In fact, he doesn’t even make an appearance in the book until quite some time after she arrives in Aragorth…or does he?

I loved the concept of the sky ships, and I would have loved to have seen more of the implications of the setting in terms of the land being set in the sky. I also would have enjoyed seeing a little more of the steampunk influences in this world. Speaking of steampunk, I would say that the artifex Kantelvar was probably my least favourite character, simply because I thought his character could have been a little better developed and his motivations a little more robust that what Craddock gave us here.

Great writing, strong characters, twists and turns, a hint of steampunk, political intrigue and sinister magic…as I stated at the beginning, all in all An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors is a fun read. Craddock has given us a treat in this book, and I’m looking forward to reading the other two books in the Risen Kingdom series.

The post Review: An Alchemy of Masques and Mirrors, by Curtis Craddock appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

October 26, 2020

Battles of Anglo-Saxon England: Chester, AD 616

Note: this post is part of a continuing series on the Battles of Anglo-Saxon England, which includes the following posts:

Battles of Anglo-Saxon England: Weapons and Armour

Battles of Anglo-Saxon England: Badon

The Battle of Chester was a major victory for the Anglo-Saxons in the early 7th century against a combination of Welsh forces and possibly some of Mercia as well. It has some interesting features to explore. For one, it is the earliest British battle where the location is known, near the present-day city of Chester at what is now called Heronbridge. But more about that later.

Before I can give information about the battle itself, we have to take a few steps back and have a look at some of the background to the conflict and examine what we know about the main players.

This battle is mentioned in more than one ancient source. Most of what we know about it comes from the hand of Bede, who wrote about it in his Ecclesiastical History of t English People in AD 731, approximately one hundred years after the battle. Because of the fact that he uses British (ie Welsh/Celtic) names in the account, it is thought by some scholars that he had access to a British source for the account of the battle which has now been lost. So, it is likely that his account has some accuracy.

There is mention of the battle in both the 9th-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as well as in the Welsh Annales Cambriae (10th century), but in both these cases, it is merely a one-line account of it happening, without many details. There are also some one-line mentions of the battle in the histories of various Irish kingdoms.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (12th century) includes a record of the battle, but because much of his work is seen as being more akin to fiction and myth than it is to actual facts, it’s difficult to ascribe much truth to what he says about it. However, in this case, it is possible he had some Welsh sources that Bede did not, which might account for the conflicting details in his account.

So, back to Bede. While he gives us an obviously carefully researched and extensive account of the battle, keep in mind that he wrote with various agendas in mind, too. In particular, part of the reason for his book is to demonstrate the superiority of the Roman Catholic practice of the faith over the (in his mind) errant Irish church practices. This is a theme that runs through much of the beginning of the Ecclesiastical History as he recounts what happened in England before the Roman church gained superiority over the Irish one.*

In this case, the battle is framed in the light of an earlier occurrence, that of the arrival of Augustine in Britain in AD 597 as a missionary sent from Pope Gregory. But the British church, established during the Roman occupation, was still thriving, so the Irish church was slightly hesitant of this newcomer muscling in on their territory so to speak. Bede recounts the meeting between Augustine and a delegation of Irish clergy, in which the Irish are bested by Augustine in a display of miracles (in other words, God proves that he is in favour of Augustine and not the Irish) and they retreat to consult with an elder bishop who encourages them to return for another meeting. This second meeting possibly took place at Chester, where there was a large and thriving British monastery nearby at Bangor. The Irish monks were charged by their elder to judge Augustine’s humility, counseling them that if Augustine rises at their entrance, showing them honour, they are to listen to him, but if he remains seated, they must dismiss his claims.

Unfortunately, Augustine does not rise at the entrance of the British clergy, and thus they refuse to listen to Augustine’s entreaties that they abandon their Irish Celtic practices regarding the dating of Easter and their distinctive tonsure (the two biggest differences) in favour of the Roman ways. There seems to be anger expressed by both sides, and at the end of the debate, with no capitulation by the monks, Augustine metaphorically washes his hands of the recalcitrant British churchmen and states that because they would not listen they would suffer war from their enemies, and because they would not join with him in preaching to the English, the English would bring death to them.

Flash forward some nineteen years, to the year AD 616, when there was a large battle between the combined forces of the Welsh kingdoms of Gwynedd, Powys, and Rhos against Æthelfrith of Bernicia. Looking back at this battle from the 8th century, when Bede was writing his history, he infers that this battle was the fulfillment of God’s judgment spoken by Augustine against the British monks. He does this because in the course of the battle a contingent of monks from Bangor were slain by Æthelfrith because they were part of the British forces. Not as combatants, at least not physical ones. They were there to pray for the success of the Welsh against the Angles. As Bede recounts it, Æthelfrith spots the monks standing apart from the gathered British warriors. He asks who they are and discovers that they were priests from Bangor, praying for the success of the British.** Bede then recounts Æthelfrith’s response and details what happened next:

“If they are praying to their God against us, even if they do not bear arms, they are fighting against us, assailing us as they do with prayers for our defeat.” So he ordered them to be attacked first and then he destroyed the remainder of their wicked host, though not without heavy losses.

Æthelfrith emerges the victor of this battle against the British, neatly tying up Bede’s summary of the event as a fulfillment of Augustine’s prophecy against the heretical Irish church.

Bede doesn’t give us an explanation for the battle aside from that one. In fact, its a bit of an odd explanation, for Æthelfrith was a pagan, and although the accounts vary about it, there is consensus that he killed a number of monks in his victory. Bede goes so far as to call the monks that wicked host, which seems a bit harsh. But with Bede mainly silent on the causes of the battle, we have to turn to what we do know to figure out exactly why these two armies met on that fateful spring day.

First of all, Chester, which is on the borderland between present-day England and Wales, is a long way south from Northumbria. Why has Æthelfrith mustered a large army to go all that way across hostile enemy territory? It’s interesting to note that this was not the first battle that Æthelfrith fought against the British. He had been successful in other battles before, gaining the nickname, “Fleseur” or “the Twister” from the British, indicating a perhaps wily and duplicitous nature. Bede says that Æthelfrith, a pagan king, “ravaged the Britons more than all the great men of the English”, so he was clearly a formidable fighter. He also conquered other Anglo-Saxon kings and in AD 604 gained control of Deira (the southern half of Northumbria), possibly by conquest. Edwin, son of the former king of Deira, then went into exile as a child. However, some historians speculate that Edwin might have been part of the opposing Welsh coalition forces at the Battle of Chester, which could explain Æthelfrith’s motivation for this fight: to rid himself of a powerful rival.

Other facts that we do know include:

it was fought at the beginning of the 7th century, dates range from AD 607- 616. The earlier dates are generally discounted, and Bede’s date of AD 616 seems reasonable.

Æthelfrith led a force of men to Chester and fought against a combined force of Welsh/British troops

a number of monks were slain (numbers range from 200 to 10,000!).

there appears to be someone named Brochmael (he has different names in different accounts) who was supposed to protect the monks but who ran away at the first sign of trouble (Bede); or who was an inept fighter who shows up late in an unsuccessful rear-guard maneuver (Monmouth).

the battle was fought near present-day Heronbridge.

cause of the battle is unknown, although historians speculate an offensive strike against the Welsh by Æthelfrith in order to rid himself of a rival, or a raid aiming to loot the wealthy Welsh kingdoms. It seems unlikely that it was the Welsh who were on the offensive, since it is so far from Æthelfrith’s kingdom of Bernicia.

Æthelfrith and his Northumbrians came out the winner of the battle, although it seems there were heavy casualties on both sides

Before we leave this intriguing battle, I can’t let you go without mentioning one of the really interesting things about it. I stated at the beginning that this is the earliest British battle where the exact location is known. That is because, in 1929 archeological digs in the Roman remains around Chester (which had been an impressive Roman site before the Anglo-Saxon period) discovered a mass grave of bodies buried in the Roman ruins. Analysis at the time of the remains concluded that they were men between 20 and 40 who had been killed in a battle or massacre of some sort, due to the injuries on the skeletons. But over the subsequent years the location of the bodies was lost, until the early 2000s when another excavation discovered a defensive rampart built during the 7th century (likely built before or after the battle) as well as the graves.

Some of the skeletons from the Heronbridge graves. Image from Wikipedia.

The bodies had been placed side by side, some overlapping, with no grave goods. Injuries were consistent with battle wounds, many of them died from a blow to the head. Others had healed wounds, indicating they were warriors, as did the fact that their skeletons showed heavy musculature. Due to the care in which the bodies were laid in the grave, it had been speculated in 1929 that these were some of the dead from the victorious Northumbrian army. When the bodies were re-discovered, radio-isotope analysis of the men’s teeth confirmed that indeed they had hailed from Northumbria. Approximately thirty skeletons were found between the 1929 excavation and the modern-day one.

Fascinating, no? As always, there is so many gaps in our knowledge, so many tantalizing details that escape us. But how amazing that these long-dead warriors can still provide important clues as to what took place so many years ago.

***

*Side note: you might wonder why Æthelfrith doesn’t know these are monks. Surely he could tell from their dress? Well, not really. At this time the monks did not have different garments from laypeople. They were only to dress simply, without ostentation. They could have been wearing hoods, disguising their tonsures.

**Although, to be fair, as I have mentioned before, Bede did have admiration for many of the Irish clergy, especially Aidan, even holding them up as examples of disciplined devotion to Christ, which he saw lacking in his own church at times.

Note: this post is part of a continuing series on the Battles of Anglo-Saxon England, which includes the following posts:

Battles of Anglo-Saxon England: Weapons and Armour

Battles of Anglo-Saxon England: Badon

Can’t get enough of Anglo-Saxon England? Check out my books, Wilding and Bound, part of a historical fantasy trilogy set in 7th-century Northumbria, and featuring a young man whose shadowed destiny leads him to the past…and could change our world forever.

Book Three coming 2021!

The post Battles of Anglo-Saxon England: Chester, AD 616 appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

October 9, 2020

Interview: John Connell

One thing I really enjoy doing on this blog is getting the chance to interview other authors. Today I am very excited to welcome John Connell. If you missed my review of his book, The Man Who Gave His Horse to a Beggar, zip over and have a look, and then grab your favourite beverage and settle down with us as I chat with John!

Thank you so much, John, for being willing to spend some time with me on the blog today! And thank you again for being willing to donate your book as a prize for the Bamburgh Bones contest. I was so thrilled to be a winner, and I really enjoyed the book.

Thank you for inviting me, and I am glad you enjoyed the book!

First of all, give us a bit of your background and tell us what drove you to write about St. Aidan in the first place.

I grew up in rural Northumberland, in the heart of Aidan’s mission area. As soon as I was able to walk, my father took me around the castles, churches, ruins and hillforts of the region. Ever since I was a boy, I have been fascinated by the legends of the northern kings, saints and warriors. Though we lived different times, Aidan’s landmarks and mine are in some respects the same.

I wrote about Aidan rather than one of the other northern saints based primarily on a sense of justice – or rather of injustice. Given the scale of his achievements, he has been egregiously overlooked. I wanted not only to celebrate his life and legacy, but also to retell his story for a new generation that may not even have heard of him.

My long-standing interest in the early medieval period was encouraged by well-known Anglo-Saxon scholar S.A.J. Bradley at the University of York. He introduced me to Old English poems such as The Dream of the Rood and the epic Beowulf in the original. Several years later, I returned to York to pursue a postgraduate degree in Medieval Studies where I specialised in early medieval Northumbria.

Professionally speaking, my background is mainly in journalism. I have worked as a BBC-funded Local Democracy Reporter based with The Whitehaven Newsand the Times & Starand as a general news reporter for the Edinburgh Evening News. I have contributed in a freelance capacity to magazines, newspapers and radio programmes, both regional and national. I am now a Senior Caseworker for Workington’s Conservative MP, based largely in West Cumbria, but with occasional visits to Westminster.

This was obviously a big project. Why did you decide to write this book in this format, and how long did it take you to complete it?

The layout was inspired by Sacred North, a remarkable adventure in the footsteps of the northern saints undertaken by an equally remarkable man, Cumbrian Orthodox priest Father John Musther. He achieved all this despite being in his late 70s and having Parkinson’s disease. I believe him to be a living saint very much in the mould of Aidan.

The writing and research itself took about 18 months. I worked on the book around a demanding full-time job and looking after my then two-year-old daughter. There were occasions when I thought I had bitten off more than I could chew, but my partner Becky was very supportive. I owe her a great deal of thanks for her forbearance – and for not kicking me out on the street.

I haven’t read Sacred North. I’ll have to add that to my TBR list! You’ve said you’ve travelled extensively throughout Northumbria, but were there new places that you visited in the course of your research? Do you have a favourite?

On the course of his travels, John got to visit all sorts of interesting places which would have been familiar to Aidan, such as this burial cairn at Kilmartin Glen, in present day Scotland.

Many of the areas in northern England were already very familiar. I have lost count of how many times I have visited Bamburgh, Yeavering, Lindisfarne and Durham Cathedral. However, the locations in Ireland and the Hebrides were all new to me. The ancient prehistoric monuments of Kilmartin Glen in Argyll and the ancient stronghold of Dunadd were particularly impressive. It may seem a rather ‘obvious’ answer, but Iona made perhaps the greatest impression on me. The quality of the light and the palpable aura of sanctity were profoundly moving in a way I struggle to articulate. I can understand why George Macleod, founder of the Iona Community, described the island as “a thin place where only tissue paper separates the material from the spiritual.”

Iona is high on the list of places I want to visit, that’s for sure. After Lindisfarne! Your photographer, Phil Cope, as well as the actor who “stands in” for Aidan in some of the photographs, both add unique elements to the book. How did their involvement come about?

I was inspired by Phil’s photography in Sacred North. I approached him, initially by email, with a view to enlisting his help on my own project. He liked my pitch and we took it from there. We decided very early on that the tone of the book would not be too ‘academic’. The point was to make Aidan’s story accessible to everyone. This re-telling of Aidan’s life was not simply to be aimed at Christian pilgrims or history-lovers. We both felt that his message is much broader than that and is pertinent to our own times.

I wanted to remind people that Aidan was a man before he was a saint. This was why I took such pains to explore his possible foibles and flaws. By its very nature hagiography creates very ‘flat’ and formulaic characters. This makes it challenging to give the impression of a three-dimensional personality. However, this is not simply a book about religion and old ruins: it is a story about a man who changed the world.

I had a picture in my head of what Aidan looked like: a lean outdoorsman, bearded and weather-beaten, as you would expect of a man who spent so much of his time wandering the wilds The mission was to find someone who would help ‘resurrect’ our hero. Having a real bloke play Aidan was a quite deliberate to device to made him a less remote figure.

I approached my former colleague and good friend Liam Rudden, the Entertainment Editor of the Edinburgh Evening News. A writer, director and presenter with extensive contacts in the industry, he put me in touch with Eric Murdoch. A tour guide and actor who goes by the soubriquet of ‘the Tartan Viking’, Eric has appeared in Robert the Bruce (2019) and in hit TV series Game of Thrones. He became Aidan for the day. We did a shoot in the spectacular coastline of East Lothian. The overgrown ruins of Auldhame Castle, Seacliffe Beach, St Baldred’s Cave and Aberlady provided the backdrops. The greatest challenge was finding a horse which we borrowed from a riding centre at very short notice to recreate the episode in Aidan’s life from which the book derives its unusual title.

You explain in the book that Aidan’s life became somewhat overshadowed by Cuthbert, who came after Aidan. Why was that? Why doesn’t the average person know much about Aidan today, do you think?

When Cuthbert’s coffin was reopened a decade after his death, his body was apparently found relatively ‘fresh’. This gave his cult an immediate boost. However, it is difficult to disentangle truth from ecclesiastical spin. As late as the sixteenth century, there were reports that his body was still incorrupt. When Henry VIII’s commissioners came to loot the tomb in Durham, St Cuthbert was found whole, with his beard as if it had a fortnight’s growth!

But there were also political reasons why Cuthbert’s fame waxed as Aidan’s waned. Cuthbert presented a much firmer foundation for the edifice of a saintly cult than his predecessor. He was ‘Anglo-Saxon’ rather than Irish and was a safer bet with the emergence of a sense of English nationhood in later centuries. Aidan was also a tainted figure because of his association with ‘Celtic’ Christianity and being on the losing side at the Synod of Whitby.

Aidan’s cult may also have been actively supressed following the Synod which split the Church in Northumbria. Theodore of Tarsus, Archbishop of Canterbury from 668 to 690, issued strict instructions that people were not to pray for the souls of ‘heretics’, or even venerate a devout heretic’s remains, a clause which academic Marilyn Dunn suggests may refer specifically to the relics of Aidan that remained on Lindisfarne.

The popular appeal of Cuthbert’s legend also derived in no small part from the remarkable story of how the monks of Lindisfarne carted his coffin about for seven years to escape from the Danes before receiving intimations that Durham was their divinely-appointed destination. An impressive foundation legend like this would have given the town’s status a huge lift, helping to promote a flourishing pilgrim trade. Cuthbert’s cult may have been a product of the genuine love and respect he commanded from ordinary people, but it is also true to say that this was seized upon by clerics to increase their own wealth, status and power as they basked in a reflected glory that was in some senses real, and in others manufactured by the Church.

John getting in touch with his inner warrior at Bamburgh.

What do you think was Aidan’s greatest challenge in bringing the Gospel to the Northumbrians? And why was he so successful?

It is difficult to know where to start, so manifold and complex were the obstacles he faced. The most obvious and immediate problem was the language barrier, which would have made it more difficult to get his message across. Aidan spoke a dialect of Old Irish, but his adoptive people spoke a Germanic tongue known retrospectively as ‘Anglo-Saxon’ or ‘Old English’. He would probably have encountered some initial hostility from the local population and some resistance to his message from Anglo-Saxons reluctant to abandon the religious practices of their forefathers. The population of Northumbria had also been ravaged very recently by an invading army. The people had every reason to be distrustful of strangers.

You also have to consider the vast size of Aidan’s mission area, which extended from the Firth of Forth in the north to the Humber in the south; and from the North Sea in the east to the Irish Sea in the west. This must have presented huge logistical challenges for the Gaelic monks who came here at great personal risk to convert the pagan English. The landscape was more densely-forested than today and there was very little in the way of infrastructure, with the exception of the overgrown semi-derelict Roman road network. The quickest way to get anywhere would have been by boat or on horseback. Aidan, however, usually chose to walk, making his achievements nothing less than astounding.

Aidan’s success was dependent to some extent on the patronage of his king Oswald who even acted as his personal interpreter on some occasions. That said, this was also a ‘bottom up’, grassroots movement involving the ordinary people. Aidan’s hands-on approach and his ability to connect with the everyday folk he encountered on his many journeys would have been key. Being too hard line would have risked alienating the people he was trying to reach, so he would have need to have shown high levels of patience, understanding and determination.

He led by example and did not expect his followers to do anything that he was not prepared to do himself. Aidan refused to insulate himself from the grinding poverty, disease and suffering he must surely have encountered. He showed himself to be a strong, even stubborn personality, unwilling to be cowed or intimidated by those in power.

Aidan died only twelve days after his friend, Oswine, King of Deira, who had been murdered by Oswy of Bernicia. You discuss this a bit in the book, but do you think that these two deaths were linked?

Yes, I do. Bede makes a point of recording that Aidan died just eleven days after his beloved king, Oswin, had been treacherously put to death by Oswiu. Bede’s juxtaposition of the two events suggests they were connected in some way, though we cannot be sure exactly how.

One scholar has suggested a more sinister link between Aidan’s death and that of his friend Oswin. The indication is that Oswiu wanted Aidan out of the way, perhaps because the Irishman was growing increasingly outspoken in his criticism of the king’s behaviour. It would certainly have benefitted the king to have Aidan replaced with someone more tractable. However, my personal view is that Aidan died of a broken heart following the death of his close friend, worn out from his many labours.

What do you think is Aidan’s greatest legacy?

Re-establishing Christianity across the north was his greatest achievement. His legacy is not as easy to pin down or to quantify. This is the reason I wrote the book in the first place. I wanted to raise his profile nationally and internationally at a time when so many people in the west are turning their back on their religious heritage.

I also hope that Aidan’s connections throughout the ‘British Isles’ will help heal some of the historical divisions that are still with us. He has been mooted as a patron saint of the British Isles. Perhaps his greatest legacy could be a greater recognition of what we all share, here and elsewhere. A pilgrimage route linking some of the places visited in the book would be an excellent way for people to connect with one another, with their past, and with Aidan himself.

If you could ask Aidan one question, what would it be?

I would ask for his blessing.

Besides Aidan, is there anyone else from the early medieval era that you would like to write about?

Penda is a fascinating character. A contemporary of Aidan, it is difficult to imagine someone more different. His psychopathic violence; his penchant for fire-starting, his paganism; and his energetic military campaigns would make him an interesting subject.

Oh yes, Penda fascinates me, too! What are you working on now? Do you have any more books with a similar format planned?

I would love to write another book and I have several ideas in the pipeline, including a children’s book. But I suspect I would find my clothes in bin bags outside the front door if I started another literary venture quite so soon after this one. My focus is very much on my family, my job and with promoting the book. However, I will be sure to keep you posted!

Thank you so much, John. I really enjoyed chatting with you today!

If you want to keep up with John on the interweb, you can connect with him on Facebook on his book’s page, The Man Who Gave His Horse to a Beggar, where he posts all sorts of interesting info about Early Medieval England. He also can be found on Twitter @aidan_all.

If you, too, have a hankering to wander around Northumbria after reading that interview, don’t let COVID stop you! My historical fantasy books, Wilding and Bound, are set in 7th-century Northumbria and they even include Aidan himself as one of the characters!

The post Interview: John Connell appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

September 28, 2020

Book Three, Here I Come!

Now that the dust of the launch of Bound has settled I am setting my sights firmly on Book Three and working full steam ahead on the conclusion of The Traveller’s Path trilogy.

I’m not starting from scratch, however. I have already completed a draft of the MS, and during the time I was doing final edits on Bound, I also set aside time each week to do a little work on Book Three. I’m very glad I did that. The third book is the one that needed the most work, so that allowed me to do some thinking about the plot and where I could make it better.

It definitely needed more action and more complications in the plot. And as I thought about the entire series, I knew there were threads that I need to finish up in order to have a satisfactory ending to it all.

Threads like:

Does Thomas get home or not? If not, why not?

Will Thomas be successful in thwarting Wulfram’s plan?

What about Nona?

What about Godric?

What about Nectan, Raegenold, and the rest of the Fey? What part will they play in the final showdown between Thomas and Wulfram?

One of the challenges I have faced in writing the series the way I did (as one whole story to begin with and then breaking it up into three), is that I’ve had to add subplots or develop characters a little more fully here and there to help fill out the plot and to make each book as entertaining as I can. That has had some happy consequences. Godric is one of those characters who has received some extra stage time, and I think the books are better for him having a bigger role.

Nectan, the Seelie King of the North, also got a bigger stage, and I’m glad of that, too. But now I’m considering who else might step onto the main stage to help bring the books to a conclusion. One of the existing characters, or is someone new waiting to find the spotlight? Stay tuned!

Character Development

I really want this last book of the trilogy to be the most satisfying yet. Along with an exciting and intriguing plot, and bringing the story to a satisfying conclusion, this is my last chance to fully explore all of these characters and what makes them tick. I especially want readers to understand more of Thomas and his emotional journey throughout. That means a deep dive into character development.

I’ve discovered a great new tool to do this, the One Stop for Writers, which is really helping me with going deeper into Thomas’ character. What has he learned so far? What does he need to learn in order to fulfill his quest? How will his character flaws and strengths add to the complexity of the book?

I’m excited to explore all of this and bring you a book that will be the best one yet. I don’t want to disappoint my readers! I’m really excited about the plot…the final climax of the book is a doozy!

So, onward and upward! I’ll continue to give you updates here as the book progresses, but, don’t forget, if you really want the latest news, please sign up for my newsletter. You’ll be kept up to date with the latest in publication news, plus you get some exclusive fun stuff and bonuses that are just for subscribers. Click on the link above or below on this page to sign-up.

And, as always, if you have any thoughts on this or suggestions on what YOU would like to see in Book Three, leave a comment below!

The post Book Three, Here I Come! appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

September 11, 2020

Review: The Man Who Gave His Horse to a Beggar

I had a really exciting thing happen to me earlier in the year. I won a contest sponsored by the Bamburgh Bones, the wonderful project created to tell the story of the people who were buried in a cemetery near Bamburgh in Anglo-Saxon times.*

The prize for winning was a copy of a new book, The Man Who Gave His Horse to a Beggar, by John Connell. I had seen this book being advertised during its launch and was really intrigued by it. To be the winner of one of three copies made me very happy, and as soon as I got it, I delved in.

The book is all about Aidan, Abbot of Lindisfarne, and is subtitled, Following in the steps of Aidan of Lindisfarne, the saint who walked to heaven through Ireland, Scotland, and the north of England. I have a huge appreciation for Aidan. Those of you who have read my books will see him appear in my books. My main character, Thomas, spends quite a bit of time at Lindisfarne and gets to know Aidan during his time in 7th-century Northumbria. So to win this book was such a treat!

Connell is a journalist and writer who lives in Northumberland. His bio says that he has been fascinated with the stories of the kings, saints, and warriors of that area since he was young. His book is a wonderful compilation of photographs, travel diary, and history as the author follows in the footsteps of Aidan from the saint’s home in Ireland to Northumbria and beyond.

Along the way we learn more about Aidan himself and the times in which he lived. Connell breaks up the book into six journeys: Little Fire (Ireland), Footprints in Stone (Scotland, northern England), Heartlands (Bamburgh, Lindisfarne, and the Farne Islands), Hinterlands (the Anglo-Scottish Borders), Ruins and Frontiers (Roman Wall country and beyond) and Legacy and Loss (Tyne and Wear, Durham and North Yorkshire). Each of these areas had a part in Aidan’s story. Paul Cope’s extensive photographs throughout help us to picture the locations, and a running fictional narrative sprinkled throughout the mainly non-fiction text brings us a little deeper into Aidan’s world. The title refers to a story that Bede tells about Aidan, in which King Oswine of Deira gifts Aidan a horse with regal fittings to aid in his missionary travels across England, but Aidan, when he comes across a beggar, gives him with his horse. Upset at this casual dismissal of the gift, the king confronts Aidan. As Bede tells it,

The King asked the bishop as they were going in to dine, ‘My Lord Bishop, why did you give away the royal horse which was necessary for your own use? Have we not many less valuable horses or other belongings which would have been good enough for beggars, without giving away a horse that I had specifically selected for your personal use?’ The bishop at once answered, ‘What are you saying, Your Majesty? Is this child of a mare more valuable to you than this child of God?’”

Suitably chastised, the king apologizes and vows never to question Aidan’s generosity again.

An example of some of the photos in this book.

One of the things I noticed when I first started doing researching Aidan for my books was that his contribution to English history seemed in my eyes to be much bigger than one would assume from his rather muted legacy. It was clear that he played a pivotal role in 7th-century England and yet, as Connell explains, often his part in history is eclipsed by those who came after. Particularly Cuthbert, whose legacy in many ways grew in proportion to the loss of Aidan’s.

The Man Who Gave a Horse to A Beggar does a good job of explaining this. We learn that one of the reasons why Aidan’s legacy became hidden in Cuthbert’s shadow was the rift between the Irish “Celtic” Church that Aidan represented and that of the Roman Church followed by Cuthbert and those who came after. Although both Churches agreed on the main points of doctrine, there were several practices and customs that separated them, and it became clear that one had to prevail. Shortly after Aidan died, the Synod of Whitby was convened to settle the question of which set of practices would be followed by all the churches of England, and the Celtic Church lost out to the Roman one. Aidan and those who followed the Irish Church’s methods of dating Easter, the style of the monk’s tonsure, and other practices were seen as almost heretical by the winners of this debate, and so the “winning” side got to work in promoting their saint, Cuthbert, as well as those who followed him. Aidan was quietly shuffled over to the side.

But thankfully, the Venerable Bede, although he was part of the Roman church, had a great affection for Aidan and some of the other Irish clergy, and so he gave a sympathetic slant to their stories in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Which was quite remarkable, on the face of it. Bede admired their tough, aesthetic spirituality, especially in comparison to some of the excesses he could see developing in his contemporary brethren. We owe a great deal of credit to Bede for keeping the story of Aidan and the other Irish churchmen and women alive.

I enjoyed this closer look at Aidan and his world in The Man Who Gave His Horse to A Beggar. I’m glad that in it, Connell continues Bede’s tradition of giving Aidan his due. He gives us a portrait of a fascinating man and the times in which he lived and helps us to understand why Aidan’s legacy is still so important to us in our troubled times today. I highly recommend it!

*Warrior: A Life of War in Anglo-Saxon England, by Edoardo Albert, is the story of one of those people.

Want more on Anglo-Saxon England? My historical fantasy series, The Traveller’s Path, is set in 7th-century Northumbria and features a young man whose shadowed destiny leads him to the past, and could change our world forever. The first book, Wilding, was published in 2019 and the second book, Bound, was just released in the summer of 2020.

The post Review: The Man Who Gave His Horse to a Beggar appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

August 28, 2020

Book Launch Wrap-Up!

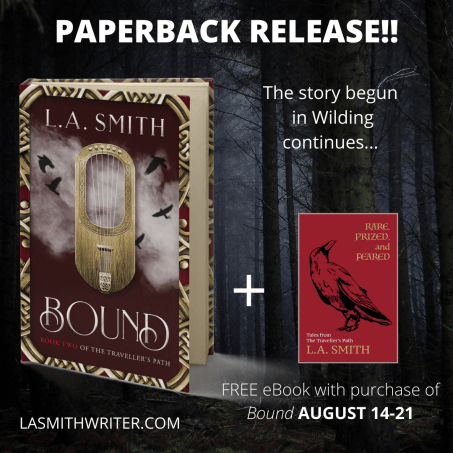

It’s been a busy summer around here. On July 1st, I launched Bound, the second book of my historical fantasy trilogy. Due to various circumstances I was only able to release the ebook format at that date, although I had originally planned that I would launch it in both ebook and paperback. I had been advertising July 1st as the launch date, so I went ahead with the ebook launch and decided to launch the paperback later, when it was ready.

To get ready for launch I planned a whole series of emails to be sent to my newsletter subscribers, who got a sneak peek at the cover, the prologue and first chapter, plus an early heads-up on the bonuses I was offering to those who purchased Bound in the first week. So in the couple weeks leading up to July 1st, those who have subscribed to my newsletters got all of those goodies delivered to their inboxes.

I also planned a bunch of social media posts via twitter, Facebook and Instagram, and scheduled them so they would appear throughout launch week. I did all of this again for the paperback launch in August, minus the extra newsletters.

Phew. This seems like a lot, but honestly, it’s really not. These days authors do a WHOLE lot more to launch their books. They set up blog tours, podcast interviews and other promo appearances, as well as cross promos with other authors. Many plan for and execute extensive giveaways for launch. These can include book bundles, artwork designed around their books, extensive character sketches, maps, and/or reams of other special “swag” for those who attend book launch parties or host contests for readers to win these prizes.

Um, yeah. You might have noticed that I did NOT do any of those things. I really admire authors who can do all this. I hope to get better at it. But honestly I was so swamped with doing all the stuff that I did do that I don’t know how I could possibly fit more in.

So, what were the results? Here’s a summary:

THE GOOD:

Some books were sold! Ok, I didn’t exactly reach the bestseller list but it was very satisfying to hear from people who were happy and excited to get the next book.

I learned more stuff! I made some mistakes, even with all my careful planning. But I have made note of those so hopefully I can avoid that next time. One of those was the difficulty I had in changing the prices on Wilding. I “thought” I could do that easily…nah. So, apologies to anyone who looked to buy Wilding on sale but then saw that it wasn’t. The sale price did show up eventually for part of the week, but unfortunately not all of launch week, and not in every online retailer. The intricacies of Amazon and IngramSpark pricing did me in. And I had a different issue altogether with Apple. Ack. I need to do more study on this, obviously.

On to Book Three! Now that I’ve bustled Bound out the door, I’m turning back to Book Three and am hard at work on the conclusion of the trilogy. More to come on that later…

THE BAD:

Frustrating problems! Along with pricing difficulties, I ran into a couple of other issues

one in particular being difficulties in updating the manuscripts in order to place the link for the bonus collection.Because of that I suspect that some of you might have bought Bound during launch week but did not get a book with the link. So, to rectify that, in my September newsletter I am including the link for the Rare, Prized, and Feared, the FREE collection of short stories and extra chapters from the world of The Traveller’s Path. Sign up for my newsletter BEFORE Sept. 15th, 2020 or you’ll miss it! Follow the link at the end of every page on my website to sign up.

one in particular being difficulties in updating the manuscripts in order to place the link for the bonus collection.Because of that I suspect that some of you might have bought Bound during launch week but did not get a book with the link. So, to rectify that, in my September newsletter I am including the link for the Rare, Prized, and Feared, the FREE collection of short stories and extra chapters from the world of The Traveller’s Path. Sign up for my newsletter BEFORE Sept. 15th, 2020 or you’ll miss it! Follow the link at the end of every page on my website to sign up.THE UGLY:

Well, nothing was TOO ugly. Except maybe my hair as I was pulling it out trying to fix the above issues.

All in all, it went well and I am so grateful to all of you for your support.

NEXT STEPS:

There is so much to learn about how to do all this. I am getting better at some things, but still have a lot to learn. One of the challenges I have right now is discoverability. I have pretty much tapped out of my larger circle of friends/family in terms of readers. I need to get my books seen and noticed by a wider audience. This is not easy. But I am stretching my wings a bit and trying a couple of new things. In the next couple months I will be a guest on a podcast and also will be trying out an Amazon ad.

I have also joined a Mastermind group to get encouragement and help with marketing, as well as joined a few Facebook groups on various topics from Anglo-Saxon history to indie publishing in order to get more information as well as connect with potential new readers.

I’m looking forward to the next steps! Thanks for joining me on my journey. Your encouragement means the world to me.

If you enjoy my books, you could help me out immensely by:

Rating the book on Amazon, Kobo, Goodreads, or wherever you bought the book.

Telling others about it in your circle of friends/family.

Sharing my posts on social media.

The post Book Launch Wrap-Up! appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.

August 19, 2020

Music in Anglo-Saxon England

Today I’m honoured to be featured on J.L. Rowan’s blog, The Realms of Talithia, where I discuss musical instruments in Anglo-Saxon England. Click the link to check it out!

Don’t forget...I’m celebrating the paperback launch of BOUND by offering a free collection of short stories/extra chapters if you purchase it this week (either ebook or paperback). You’ll find the link in the book, but only this week! AND Wilding is on sale, too!

Offers apply August 14-21st, 2020

The post Music in Anglo-Saxon England appeared first on L.A. Smith Writer.