Rick Hall's Blog, page 2

April 14, 2023

The Ottendorf Cipher

A book cipher, or Ottendorf cipher, is a cipher in which the key is some aspect of a book or other piece of text. Books, being common and widely available in modern times, are more convenient for this use than objects made specifically for cryptographic purposes. It is typically essential that both correspondents not only have the same book, but the same edition.

Traditionally, book ciphers work by replacing words in the plaintext of a message with the location of words from the book being used. In this mode, book ciphers are more properly called codes. This can have problems; if a word appears in the plaintext but not in the book, it cannot be encoded. An alternative approach which gets around this problem is to replace individual letters rather than words. One such method, used in the second Beale cipher, replaces the first letter of a word in the book with that word’s position. In this case, the book cipher is properly a homophonic substitution cipher. However, if used often, this technique has the side effect of creating a larger ciphertext (typically 4 to 6 digits being required to encipher each letter or syllable) and increases the time and effort required to decode the message.

Choosing the keyThe main strength of a book cipher is the key. The sender and receiver of encoded messages can agree to use any book or other publication available to both of them as the key to their cipher. Someone intercepting the message and attempting to decode it, unless they are a skilled cryptographer (see Security below), must somehow identify the key from a huge number of possibilities available. In the context of espionage, a book cipher has a considerable advantage for a spy in enemy territory. A conventional codebook, if discovered by the local authorities, instantly incriminates the holder as a spy and gives the authorities the chance of deciphering the code and sending false messages impersonating the agent. On the other hand, a book, if chosen carefully to fit with the spy’s cover story, would seem entirely innocuous. The drawback to a book cipher is that both parties have to possess an identical copy of the key. The book must not be of the sort that would look out of place in the possession of those using it, and it must be of a type likely to contain any words required. Thus, a spy wishing to send information about troop movements and numbers of armaments would be unlikely to find a cookbook or romance novel useful keys.

Using widely available publicationsDictionaryAnother approach is to use a dictionary as the codebook. This guarantees that nearly all words will be found, and also makes it much easier to find a word when encoding. This approach was used by George Scovell for the Duke of Wellington’s army in some campaigns of the Peninsular War. In Scovell’s method, a codeword would consist of a number (indicating the page of the dictionary), a letter (indicating the column on the page), and finally a number indicating which entry of the column was meant. However, this approach also has a disadvantage: because entries are arranged in alphabetical order, so are the code numbers. This can give strong hints to the cryptanalyst unless the message is superenciphered. The wide distribution and availability of dictionaries also present a problem; it is likely that anyone trying to break such a code is also in possession of the dictionary which can be used to read the message.

Bible cipherThe Bible is a widely available book that is almost always printed with chapter and verse markings making it easy to find a specific string of text within it, making it particularly useful for this purpose; the widespread availability of concordances can ease the encoding process as well.

SecurityEssentially, the code version of a “book cipher” is just like any other code, but one in which the trouble of preparing and distributing the codebook has been eliminated by using an existing text. However this means, as well as being attacked by all the usual means employed against other codes or ciphers, partial solutions may help the cryptanalyst to guess other codewords, or even to break the code completely by identifying the key text. This is, however, not the only way a book cipher may be broken. It is still susceptible to other methods of cryptanalysis, and as such is quite easily broken, even without sophisticated means, without the cryptanalyst having any idea to what book the cipher is keyed.

If used carefully, the cipher version is probably much stronger, because it acts as a homophonic cipher with an extremely large number of equivalents. However, this is at the cost of a very large ciphertext expansion.

June 19, 2020

Chapter 2 – The Creative Hook

Establishing the Creative Hook

After struggling through audience analysis in Chapter 1 – the most fundamental constraint of creating entertainment – it’s normal for creative folks to feel a little deflated. We picture ourselves as ‘creative’, and more often than not don’t want to think of the process as being so clinical. We reach for those flashes of insight that set our ideas apart from others.

Unfortunately, most creative people have a haphazard, unpredictably intuitive approach. We know that as professionals, we are expected to meet deadlines. Yet we also know that it isn’t possible to force ourselves to have a creative thought.

Go ahead and try. Right now. Say something creative.

It isn’t easy is it? When most people are taken unaware by a question like that, a deer-in-the-headlights look appears in their eyes. They stammer for a moment and, for most of them, the first thing out of their mouths is either something incredibly weird like “let’s go into the kitchen, grab some lint from under the fridge, and make a sandwich out of it,” or they ask a question like “Creative how? Like something funny? Inspirational? Poetic?”

The first example, something so bizarre that it probably isn’t a phrase that has ever been uttered before, might qualify as ‘creative’ to some people, but true creativity has to be more than stringing together a collection of words that are only interesting because that they haven’t been arranged in that order before. If that constituted creativity, then we could just pin some dictionary pages to a wall and hand some darts to a roomful of monkeys, and the world would be hailing it as a creative breakthrough.

The second reaction, asking questions in order to narrow down the field of possibilities, is more useful and instructive. It gets at the heart of the creative process. Let’s take a moment to understand that.

Many years ago, I found a useful definition on the creativelearning.com website. It defined the creative process as “the forming of associative elements into new combinations which is in some way useful. The more mutually remote the elements of the new combination, the more creative the idea is.”

Although that’s an incredibly useful definition, you might have to read it over a couple of times to get the gist of it. Try focusing on the phrases “in some way useful,” “forming of associative elements” and “mutually remote.” These three phrases are the keys, so let’s take a look at them individually.

In some way useful – This is the reason that the lint sandwich doesn’t qualify as creative. Simply jamming two ideas together that have no connectivity between them is random – difference for the sake of difference. We are left with something that can’t exceed the sum of its parts. It is different, that’s true, but it’s also pretty useless. What can you do with a lint sandwich as a concept? Nothing. Combining two concepts together when they have no chance of enhancing each other is pointless.

Forming associative elements – This part of the definition is the central core of the creative process. Associative elements are two or more ideas that are somehow related or connected. For instance, we commonly associate the color green with money. For Americans, at least, that’s obvious because paper money uses green ink. Creative people, rather than looking at the common connections between ideas, have the ability to find the unusual connections. If robust and interesting enough, these connections are what enable the useful element of the definition.

Mutually remote – This part of the definition is a refinement of the associative element component. When the two elements are too closely connected, it leaves no room to explore the nature of their connection. Try reading that last bit again: the nature of their connection. The way in which two ideas are connected is really the thing that we identify as creative. That unusual connection is what engages the audience’s brain, and makes them speculate and wonder. So, when the two ideas are known to already be connected, like vampires being predators, the result is uninteresting. It’s a cliché. The best examples of mutually remote ideas cause observers to see both ideas in a new light, and spawns further ideas from that starting point. In other words, the connection, that entity which forms the bridge between the two ideas, is the important part. This is what enables the mutually remote ideas to exceed the value of their sum. Individually, each idea can be simple and mundane, but when combined together, they create new possibilities.

This discussion allows us to modify our definition for the creative process, which will introduce some useful nuance.

The creative process is the associative effort by which a distant connection between two seemingly disparate ideas can be found. The nature of this connection must be unusual and cause the observer to see both ideas in a new and usual way, thus, engaging the observer’s own creativity.

Note the final phrase: thus, engaging the observer’s own creativity. This is an extremely important part of our definition. With enough experience, we eventually realize that we can tell that an idea is creative when the audience sees ways to use it that we didn’t.

In other words, a truly creative idea makes the audience think, and even feel creative themselves.

Examples of Remote Associations

Let’s say we associate dragons with treasure hordes. That’s common enough that it won’t raise any eyebrows. But now, let’s focus on the word ‘horde.’ Maybe we associate that with greed. Even with that tiny step, we’ve created some distance from the original notion of a dragon. Even so, a greedy dragon is still dull, so we need to keep at it. Create some more distance.

Greedy people are stingy with their money. Personally, I find this behavior to be obsessive compulsive. When we apply this to the dragon, creating a creature that is obsessive compulsive, we are moving into more interesting territory. Obsessive compulsive people demonstrate a bunch of interesting behavior traits, so let’s tag our dragon with a few possibilities:

Obsessive washing or cleanliness, or a dragon neat freak

Excessive doubt or concern that if everything isn’t done perfectly, something awful will happen, or Eeyore the dragon

Excessive counting or arranging, those who are obsessed with order and symmetry, maybe Sheldon Cooper as a dragon

Fear of losing control, or a dragon control freak

A germaphobic dragon might be the reason they are so reclusive

Excessive focus on religious or moral ideas would give us a cult leader dragon whose followers think it is a god

Extreme superstitions regarding numbers, colors, symbols or arrangements, which makes me smile to think of the dragon that is afraid of black cats

Ritualized behavior might cause our dragon to be almost comically predictable, which is the only thing that gives the hapless St. George any chance at all of beating it

Extreme nervousness or anxiety. Can you imagine a dragon with the personality of Dobby the house elf?

Applying one or more of these to our dragon will result in an atypical creature – something that doesn’t conform to the stereotypical image of a dragon. Yet the plausibility of it is confirmed through our logical chain of reasoning. Obsessive compulsive behavior would make sense for a dragon, given the behavior they demonstrate in common dragon lore.

Our logic chain might look like this:

Dragon –> Collects horde –> Obsessive compulsiveness –> A nervous, germophobic, religious martinet that collects rare items in pairs, but only on Sundays

Clearly, this isn’t the standard kind of dragon we would find in high fantasy, and as such, we have a basis to dream up interesting stories, situations, and interactions. In other words, our remote association is useful.

Typically, when we think of dragons, we envision huge, red, fire belching, knight eating, damsel capturing, flying reptiles. They’re predatory, cunning, and evil. Can you say ‘cliché?’ This boring idea has been done to death thousands of times already. Been there, done that. Yawn. Creative? NOT! There’s almost nothing new we can contribute to that kind of dragon.

On the other hand, if we start thinking about our obsessive-compulsive dragon, a wealth of possibilities open up. This kind of dragon can actually have an unusual personality. If she is obsessive compulsive, perhaps it has some of the related personality disorders and neuroses.

These neuroses should make logical sense for its situation, but again, that just opens up more possibilities. Perhaps our dragon is paranoid. After all, there are a zillion St George wannabes looking to slay her. She’s probably a chronic worrier. If it’s a two headed dragon, wouldn’t it develop a split personality? What if our dragon has hyper-acute senses? Maybe she believes the distant voices she hears are actually the voice of God speaking into her mind.

You get the idea. You can sail into uncharted waters pretty quickly if you start with a concept that uses remote associations.

Over the years, students in my class on game design have used this process to provide some fun results.

Vampires –> Drink blood –> Health risks (from blood transmitted diseases) –> Vampire hypochondriac

Vampires –> Blood is food –> Blood lust (compulsion to eat) –> Eating disorder –> Morbidly obese vampire

Ghost –> Dead person –> Grim Reaper –> People fear death –> Ghost fugitive, running from the grim reaper

And even if we don’t provide the chain of logic that connects the starting and ending points, the results themselves are usually self-explanatory. It isn’t hard to provide the chain of logic that connects the following:

Alien travel agent

Incompetent alien that gives away dangerous technology

Demon in an anger management program

Therapist for AI programs who are struggling to find themselves

Shark hitman

Demon corporation that deals in souls as a commodity

Double agent with a split personality

Mary Kay vampire selling eternal youth

Emo unicorn

Alien rock star

Feminist succubus

Autistic robot

Serial killer priest

Dragon trapped in the friend zone with the captured princess who is awaiting her knight

Note how in each instance above, the two opposing ideas aren’t terribly original. We all have a stereotypical image of an alien, just like we know what a travel agent is. But it’s not the individual opposing ideas that provide the energy for creativity. The real keys to creativity are the implications that result from combining them. This is the filter through which we should measure our efforts. If combining two ideas has implications that we haven’t seen before, then chances are it’s creative. (And even if you want to quibble about the definition of creativity, it’s at least going to be entertaining, which is all that matters.)

From this point on, we’ll refer to this short sentence that establishes the remote association as the creative hook. It is a fundamental necessity of character design, and when used properly, a huge percentage of the design feeds off of this short, powerful phrase.

As a side note, you should soon realize that the broader your knowledge base, the easier it will be to come up with creative ideas. For instance, in the dragon examples above, we needed to have had enough exposure to dragons to know that they commonly have treasure hordes. We also needed to have some limited exposure to psychology in order to connect greed to obsession, and then later to various neuroses or obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Sometimes you will have to do some research about the base subject in order to get some ideas, but in general, the more you read, watch movies, play games, etc, the easier it will be to get the ball rolling. Creative people are usually voracious readers and highly methodical researchers.

Mind Mapping

Although seeing results is all well and good, it doesn’t help us if we don’t have a reliable way of achieving them. We need a structured, reproduceable method for generating ideas at will, because our tyrannical bosses always have the unreasonable expectation that we can be creative on a schedule. (And they can have that expectation because they don’t have to do it.)

Relax. Take a few deep breaths. It’s not impossible. In fact, creativity isn’t some mystical gift from the gods. It’s a skill, and like any skill, it can be learned, trained, and improved. All you need are some techniques, and happily, that’s one of the main points of this post.

The first method we’ll take a look at is a technique commonly known as a Mind Map. The term Mind Map was first coined in 1974, but the idea has literally been around for centuries. It began with some historical guy named Porphyry of Tyros in the 3rd century, when he used graphical representations to depict Aristotle’s Categories.

Since then, it has evolved an avalanche of functionality, used by educators, engineers, psychologists, scientists, etc. as a method to model systems, solve problems, and record information. For our purposes, it boils down to a tool that facilitates problem solving.

And that’s all creativity is: a specialized kind of problem solving.

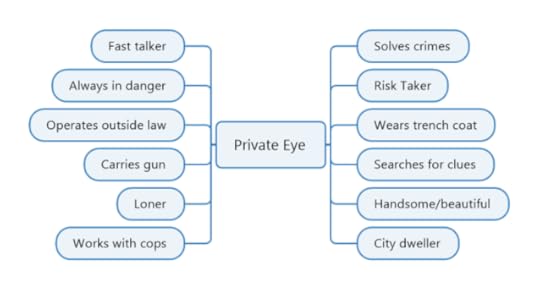

So how does it work? Let’s start by building an example. Say we want to brainstorm a new Private Investigator character. Write the words ‘Private Eye’ in the center of the page, and then create a field of little bubbles around it, with each one showing all the stereotypes we can recall that are associated with private eyes.

This represents the fairly chaotic jumble of stuff that pops into people’s heads when they think about private investigators. None of it is the slightest bit interesting, except for one thing.

This represents the fairly chaotic jumble of stuff that pops into people’s heads when they think about private investigators. None of it is the slightest bit interesting, except for one thing.

Each bubble brings with it more associations.

Recall that creativity is rooted in the ability to associate – to connect different pieces of information. And also recall that to be creative, most things have to form connections that are remote from each other. In other words, we need to extend our mind map out to the next level.

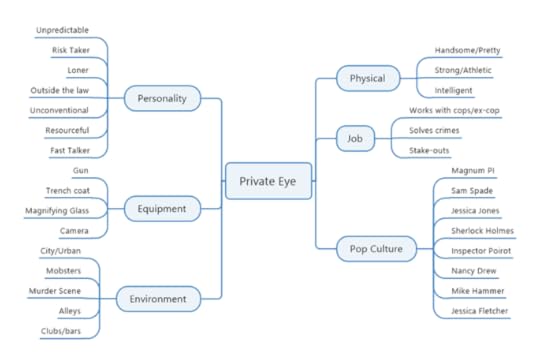

But before we do that, let’s look at our current map a little more closely. Notice how our stereotype observations each seem to belong to a kind of category. Fast Talking, Risk Taking, and Loner are all personality traits. Carries a gun and wears a trench coat are both common equipment for them.

Before we move on, it’s useful to regroup our ideas. We’ll find that when we do this, it actually shows us where we could add in even more stereotypical information. And the more things we bring to the table to associate with, the more opportunities we have for unearthing something interesting.

By this point, we’re still in the land of stereotypes, but by sorting our observations into categories, we’ve been able to provide more data to associate with. New opportunities are going to start coming into focus.

By this point, we’re still in the land of stereotypes, but by sorting our observations into categories, we’ve been able to provide more data to associate with. New opportunities are going to start coming into focus.

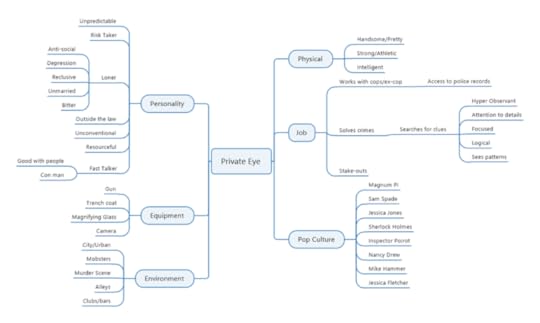

To get there, we need to look at the edges of the mind map and ask ourselves things like “what are the implications of this?” and “what does this word or concept make me think of?” That will allow us to expand it further.

At this point, if you let your mind wander over the mind maps and look for patterns around the edges, certain words and concepts will jump out at you. Viewing above, we find, anti-social, reclusive, hyper observant, unpredictable, and sees patterns.

At this point, if you let your mind wander over the mind maps and look for patterns around the edges, certain words and concepts will jump out at you. Viewing above, we find, anti-social, reclusive, hyper observant, unpredictable, and sees patterns.

Ignoring private detectives for a moment, allow this collection of words to swarm around in your head. What other sorts of people might these words apply to? Perhaps an accountant, computer programmer, doctor, or an author? Unsurprisingly, some of these occupations pop up in movies that feature amateur detectives. Jessica Fletcher is a writer. Dr. House is, for all intents and purposes, a detective who solves medical mysteries.

Or we may look at the words around the edges of our mind map and see types of people instead of occupations. The same words that jumped out at us before, “anti-social, reclusive, hyper observant, unpredictable, and sees patterns” could easily describe someone with OCD, or that obnoxious neighborhood gossip that lives down the street.

Gee, big surprise, we have Adrian Monk, an OCD private detective, and Miss Marple, the neighborhood gossip who is an amateur detective.

If we allow our mind to continue to sift through the edges of our mind map, it might occur to us that those individuals like Sherlock Holmes or Inspector Poirot constantly amaze us with their powers of observation. When Holmes walks into a room and after five seconds says something like “clearly, the killer is well over six feet tall, left handed, and plays golf… on Tuesdays,” it seems impossible. We’re sure he’s just making this stuff up, like some sort of conman or a psychic. (Oh, gee, there’s Shawn Spencer from USA Network’s Psych). Or the word anti-social, for me, leads to ASPD and sociopath (Dexter, Prodigal Son).

Or maybe it’s all some elaborate trick, like a stage magician does. Surely, there can’t be a detective who is also a magician? Yeah, actually there is. The 2018 series was called Deception, and featured a Las Vegas illusionist who became the world’s first “consulting illusionist” to work with the FBI.

The fact is, virtually any model for a detective can be found by brute force. Populate a mind map with data that you can associate with the central topic, take it out 4 or 5 levels, and start asking the usual questions like: who else does this remind me of, what does this mean, when does this happen, how does this work, why are they like this, or where do these people come from?

Nothing in the mind maps presented here requires any giant leap of imagination. Nothing requires and particular innate creative ability. It’s all rather formulaic, to be honest. And yet, once you find that unusual connection between two ideas, and you see how it can feed your imagination, you’ve found a creative hook.

Some of the ideas above that we found through straightforward, methodical observation, like Monk and Psych, were hailed as wildly creative when they first hit the airwaves, and won all sorts of awards.

Yet it really isn’t hard to arrive at the same thing.

And I guarantee that if you continue expanding on a mind map like the one above, interesting connections will appear. There are plenty of undiscovered models for private detectives. It’s only a matter of taking the time to continuously expand the map, adding more and more ideas to associate with, and exploring the results.

Also note how the mind map is nothing more than a structured approach that allows us to create the chain of logic that was discussed in the previous section. Remember how Vampires –> Blood is food –> Blood lust (compulsion to eat) –> Eating disorder –> Morbidly obese vampire? Can you see how this creative hook can be easily found by using a mind map? We populate the mind map with our associative data, and then just connect the dots from the inner concept to the outer one. Simple.

Why Does This Work?

Personally, I like to take things apart. It’s not enough for someone like me to know that a methodology works. I have to know why. So, when I first started thinking along these lines, ‘why’ was an essential question.

And the answer didn’t take long to discover. This stuff works because the connection between the starting point and the ending point, all the little stereotypical details in the inner areas of the mind map, are strongly connected to both ends. Detectives who are good at solving crimes HAVE to be observant. Not just observant, but hyper observant. And on the other side, doctors, lawyers, people with OCD, and con men are all hyper observant too. But those people come attached to an entirely different set of associations. Their traits and skills are similar to the detective, but for sometimes totally different reasons.

But it’s important that the two ideas are strongly connected by a logical thread. A supermarket cashier would be a poor template to match up with a private detective because the two occupations and personality types have almost nothing in common. But the conman and the detective? Oh yes. They both have to be fast-talking, keen people-watchers, who notice the small details, like the flicker of emotion that flashes across an adversary’s face.

I have to think that a professional poker player would make a good detective, and so would a psychologist. But maybe not an athlete or an opera singer. Of course, maybe a hook could be found if we identified a meaningful association between them. That’s the magic of creativity. It’s all about the way the ideas are connected. It’s about leveraging the commonalities, such that each side of the creative hook contributes to the result in equal measure, resulting in a new and useful spin on an old idea.

The reason anyone can do it is because the mind map itself is just a record of the exact kinds of associations that take place in the mind of a ‘creative person’, often without them even realizing it. Whether because of upbringing or because it’s their natural way of thinking, creative people are able to quickly form the connections between ideas, to see the patterns contained in the big picture and around the edges of the mind map in their heads. For the most part, this shorthand process is totally invisible to them. If asked, they’ll often say the idea ‘popped into their head’ and made sense.

The good news is that this process is reproducible. Anyone can do it. By recording the information in a visual way, where we have access to all of it at a glance, our ability to associate is enhanced. It might not result in a ‘flash of insight’, but if you’re willing to invest a few hours into mapping it all out, the results work out just the same. And the more you practice, the more you’ll develop that internal ability. After enough practice, you’ll learn how to do it automatically and be able to dispense with the mind map if you want.

Tools and Techniques

Software Options

Although it’s easy enough to draw out our mind maps on any handy white board or paper, there are also a variety of software options, both free and professional, that can be handy to help record and present your work. Personally, I use MindJet’s MindManager, but here are a few other options to consider, some free and some professional tools:

Scapple

FreeMind

XMind

ThinkComposer

MindMup

The Brain

Moo.do

Lucidchart

MindMeister

Visual Understanding Environment (VUE)

Coggle

Mind Vector

Creately

Categorization

Especially in the early stages of creating a mind map, it’s important to categorize. After your first pass at simply noting any random associations that come to mind, take the time to organize. Put each of your associations into umbrella categories, like: personality traits, physical skills and abilities, fictional and cultural examples, occupational tools, symbolism, environments, etc. By doing this, you will clarify the areas where you haven’t paid enough attention yet, and make it easier to see where you are missing possible associations. You’ll often find that behavioral and personality traits yield interesting results.

Nature of Connections

Pay particular attention to the nature of your connections. Allow this to suggest questions, symbols, and avenues for further exploration. Ask constant questions like:

Why are they like this?

Who or what else does this?

Where does this happen?

What does society think of this, and how does our central topic (or person) react to that or compensate for it?

And don’t limit yourself to asking these questions only about the central topic. Treat each element in the mind map like its only little mini mind map. It is within this kind of exploration that innovations are found. Don’t rush it. It’s often easier if you brainstorm with three or more individuals, and engage in conversation about the different ideas that appear in the mind map cloud.

Concept Mapping

There exists a similar-but-different technique to mind maps. They are called Concept Maps. People often struggle to differentiate between the two because they are similar. Mind maps are primarily used for generating and exploring ideas, brainstorming, and thinking creatively. They revolve around one main focus topic, which expands in a center-out hierarchical structure, where each node represents a specific subtopic.

Conversely, a concept map is used mostly for organizing and visualizing implied knowledge, analyzing complicated problems, and acting on the solutions. They contain larger and more complicated information, and can often be used to show how two different complex topics relate to each other. Thus, concept maps are more factual, as they identify more main concepts and the systemic and conceptual relationships between them. This means that concept maps tend to contain a lot of cross-connections between concepts, rather than being limited to the radial, center-out structure of a mind map.

So why bring this up? Well, firstly because it’s interesting. But secondly, as we will discuss in a subsequent chapter, some designs are more mechanical in nature, as opposed to the subjective ideas that we create with mind maps and creative hooks. For those designs that are more mechanics-centric, a concept map may prove to be a better choice.

Research

Creative people are voracious readers and researchers. By now, you should understand this. The larger the body of knowledge you can feed into a mind map, the more associative scope you have to work with. In other words, with more possible ideas to combine, more opportunities for innovation exist. Thus, a wide-ranging base of knowledge is extremely helpful.

Many creative people have a broad, eclectic set of interests. It surprises eve me how often a knowledge of macroeconomics creates an interesting model for a combat system in a fighting game, or a basic understanding of physics gives me an idea for a medieval fantasy character. Knowledge of different kinds of systems enables a game designer to have ‘models’ from which to draw upon. If they are good at abstracting away the details of the model, removing the specific details such that only the high-level concepts remain, these conceptual models can then be applied to an almost infinite number of other systems.

To put it another way, almost anything can be viewed as a conceptual model and applied as a filter for a wholly different system, providing an unusual vantage point from which new ways of thinking about the original concept can be obtained.

Radar Locking

Avoid the trap of becoming fixated on the first interesting pattern you find in a mind map. Yes, it is possible to come up with an original idea in an initial flash of insight. But often these flashes are based on superficial ideas – we might call them close associations – and surface level associations rarely contain sufficient depth to do anything with them.

If you stumble across an interesting looking example early in your mind mapping process, make a note somewhere, and then explicitly set it aside. When you feel like your mind map is sufficiently populated, try to find multiple creative hooks. Consider each one, seeking to understand how different it is, and how much it inspires further thought. The hook that has the greatest level of these two things is the best candidate for a creative hook.

Opposition

Sometimes, interesting results can be extracted by leaning in the opposite direction from expectations. For example, if we determine in our mind map that a typical soldier is decisive and courageous, then it might be interesting to brainstorm the implications of a soldier who is hesitant and cowardly. Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage springs to mind immediately.

This technique can yield results especially when the quality you are examining is a fundamental necessity of the central topic. In order to explore opposition, it is necessary to discover how our central topic can compensate for the missing key component. Again, exploration is required, but in this instance, it will take on a totally new direction.

Key Takeaways

Creativity comes from the nature of the connection between two remote associations

We associate creativity with ideas that are useful and unusual. Simply being different doesn’t accomplish the goal

Creativity can be brute forced simply by reproducing on paper that process that takes place in the mind of a naturally creative person

In order to form associations, a solid knowledge of the base subject is essential. Do the research

July 26, 2019

Character Generator

We’ve all heard that good characters are the lifeblood of fiction, and when I began work on Gnosis, I didn’t want to scrimp on this vital effort. In keeping with my usual manic personality, I did a bunch of research into character creation. I took my time and consumed a mountain of information on the subject. There are lots of excellent books out there, but to a certain degree, they all required a bit of ‘art’ to getting the details right. Nothing catered to an organized, systematized approach, and that’s what my brain feeds off of.

Eventually, I found my way to Myers-Briggs personality types, and quickly drank the Kool-Aid. Although MBTI types have their detractors, mainly because they’re not terribly predictive of real-world human behavior, they turn out to be perfect for creating fictional character models.

The idea behind them is that they endeavor to categorize human personalities into 16 basic types, represented by four letter combinations, like INFJ or ESFP. There are two choices of letters for each of the four positions, providing for a total of sixteen possibilities: ENFJ, ENFP, ENTJ, ENTP, ESFJ, ESFP, ESTJ, ESTP, INFJ, INFP, INTJ, INTP, ISFJ, ISFP, ISTJ, and ISTP.

These mysterious looking codes, somewhat reminiscent of genetic markers, are quite simple when broken down into their individual components. Taken from first position to fourth, the letters mean:

I or E – Introvert or Extrovert

N or S – Intuitive or Sensing

T or F – Thinking or Feeling

P or J – Perceiving or Judging

Although the terms above are somewhat misleading, if you do enough reading on the subject, they eventually make sense. If you’re utterly fascinated by this, feel free to read the definitive work by Isabel Briggs Myers, Gifts Differing.

Fortunately, as noted earlier, I’m a bit obsessive, so I did a lot more than read this one book. I read dozens. I scoured the Internet, interviewed a number of psychologist friends, and eventually cobbled together my own typing system, so I could adapt Myers-Briggs to my purposes. After about seven months of research, and a few ever-more-complicated software prototypes, I’m finally happy with the current iteration of the JavaScript tool I’ve created.

My tool basically allows a writer to quickly put together a character sketch based on a handful of dominant trait choices. You can provide as much or as little information as you want, but with each bit of data you give, the software filters the possibilities for subsequent choices. It forces you to remain consistent within existing Myers-Briggs types.

The result is that with a very minor time-investment, you can assemble a character that makes sense. It won’t be a random collection of traits that don’t belong together. It will be behaviorally consistent.

So what does ‘behaviorally consistent’ mean? Well, let’s consider a simple example. Let’s say your character is an Introvert. Generally speaking, most Introverts are uncomfortable in large group settings. They tend to be shy at parties, dress in less ostentatious ways, and are often poor at reading social cues. They even have common ways of speaking, food preferences, and hobbies. (These tendencies don’t describe ALL introverts, however. Only some of them. But that’s another discussion entirely.) This being the case, your Introverted character would most definitely not act like Tony Stark (Iron Man) from the Marvel Comics movies. Robert Downey’s version of Tony Stark is about as far along the extroverted scale as a character can get.

Unfortunately, there are LOTS of different flavors of introverts. They range from the dreamy, offbeat Luna Lovegood (Harry Potter), to ruthless ‘fixers’ like Doug Stamper (House of Cards). There are opinionated know-it-alls like Cliff Claven (Cheers), and steadfast confidantes, like Dr. James Wilson (House MD). It’s simply insufficient to label a character as an Introvert or an Extrovert, and think you have something interesting. Personalities are far more complex and nuanced than that.

My Character Creation Gadget helps you navigate the sea of possibilities, and define the core of your character. The result will be consistent with each of the components that make up a particular Myers-Briggs designation, and the best part is, you don’t have to understand how any of the psychology works. The tool will make sure you color within the lines.

Click to see the Character Creation Gadget

Click to see the Character Creation GadgetClick on the image to the right to go to my Character Creation Gadget. It will open a new browser window and load up the tool. (You may have to turn off your popup blocked to see it.) Give it a few seconds to load up all of the data files. The word “calculating…’ will be displayed in the work space while it does this. When it says “Ready”, you’re good to go. You might want to check out the “Help” button in the upper left corner first, as this will give you a quick 8 minute YouTube tutorial that shows you how everything works.

(And yes, I couldn’t resist putting a link to my novel, Gnosis, in the upper right corner of the tool. The tool itself is totally free to use, despite the amount of work I put into it. I like giving back to the writing community that gave so much to me. But if you’re of a mind to show some appreciation, please do consider following the link to my Amazon page and picking up a copy of Gnosis. It’s only 99 cents. and after the first two months, it has netted all 4-and-5-star reviews.)

A friend tells me that he had a small issue when my tool turned off his Spartan Clips software, but he was able to turn it right back on again without issue. My Character Creation Gadget is still in beta, so I’ll continue to try to resolve little issues like that. In the meantime, feel free to drop me a note if you find a bug, or have suggestions for new adjectives, archetypes, characters, etc. Enjoy!

February 15, 2019

GNOSIS – Chapter 1

GNOSIS

CHAPTER ONE

I was six months shy of eighteen when I realized my first major truth: Life is not a trust fall exercise. It’s not a team-building seminar where you can pretend to collapse, knowing your partner will catch you. In the real world, you’re just going to crack your skull on the pavement.

…which was, admittedly, a stupid thing to think about in mid-leap, thirty feet up. Jumping off buildings rarely made me philosophical, but today was turning out to be different in a lot of ways.

Arms pinwheeling, halfway between Binky’s Ink Tattoo Shop and the Cold Forge Presbyterian Church, my world lurched to a halt. It was like one of those television commercials where everything stops and the camera sweeps in a big circle around the accident that’s about to happen.

I found myself snatching at my dad’s police badge as it tugged against its chain around my neck, grasping for comfort when I should have been thinking about handholds. The world tilted in my moment of inattention; I looked up and found the ground where the sky should have been.

Then, instead of that hyper-aware calm you’re supposed to get when you’re close to death, my brain decided to shoot for weird.

Random details shoved aside any instinct for self-preservation, flooding my senses with rapid-fire sounds and images. Overflowing dumpsters snapped up at me like monstrous metal mouths. A car backfired, or maybe it was a gunshot. A flock of startled pigeons pirouetted in unison, gracefully dodging my plummeting form. For some reason, the world became too fascinating to worry about trivial things like, y’know, not dying.

Somewhere up in heaven, Dad clapped his hands with a thundering boom and hollered down at me, “Sammie, are you nuts? Snap out of it or you’re gonna DIE!”

I jolted.

No, I don’t believe in ghosts—not even Dad’s. He was dead and gone, but that imagined shout yanked me back to reality all the same.

Wind whipped a tangle of blond hair around my face. I flailed, jerked upright, and struggled against the straps of the backpack that threatened to upset my balance. Straining forward, I reached for the edge of the fast-approaching rooftop.

Air whooshed from my lungs as I slammed into the bricks. My hands clamped tight to the edge of the building, but I still bounced against it, scraping a few layers of skin from my forearms before slowing to a dangling halt.

I sucked in a shuddering lungful of air. God, everything hurt. I didn’t even want to look—between old bruises and new scratches, my skin was turning into a bad abstract painting.

I should probably invest in sleeves.

A police car sailed past the mouth of the alley as I hauled myself onto the roof. The cops inside shouted, their voices echoing in my earbuds, captured by the Teledyne 500 transmitter I’d planted under their front seat.

“… the hell? Man, that was her! Turn us around, Frank!”

Tires squealed. Crap. I hadn’t lost them after all.

Gulping for air, I lay back and pressed myself against the rooftop’s safety wall. A pair of car doors clicked open, with Bobby Kellog’s voice babbling in my ears as he talked.

“… telling you it was her. Man, that chick should wear a cape.”

Despite the situation, a smile warmed my face. Dad used to describe Bobby as the station’s “token K-9 officer.” Dumb as a post, loyal to a fault, and easily distracted by food and fast-moving objects. His voice dwindled as he walked away from the squad car, but my transmitter still caught most of the conversation with his obnoxious partner.

“Jesus, Bobby. What’s wrong with you? All that parkour crap ain’t normal for a seventeen-year-old. If her old man hadn’t been such a slacker, she’d be dating football players instead of spending her time playing monkey-girl.”

Classic Frank Walcott. Unlike Bobby, he was an Olympic-level dick. One of Frank’s favorite pastimes was comparing me, unfavorably, to his own wuss of a son. Dad had always hated him, but the antics me laugh; Frank couldn’t handle knowing a skinny blonde girl had bigger balls than his boy.

At least Bobby had a little class. “Cut her some slack, Frank. Her old man’s dead, for Chrissake.”

“So? Am I supposed to feel bad? That crack-dealing piece o’ shit made us all look bad. I swear, if the feds get any further up our asses we’re all gonna need enemas.”

“Yeah, I don’t get it. Why do we gotta–hey, lookit that! There’s hamburgers on the ground. I told ya I saw her!”

Frank snorted. “Maybe. And maybe a junkie just missed the dumpster.”

I glanced over my shoulder at my backpack’s flap to find it flopping in the breeze. I blew out an exasperated breath. The collision with the wall must have shaken my lunch free. Half a dozen freshly scrounged cheeseburgers from Mickey-D’s dumpster must be down there, pointing at me like a trail of breadcrumbs.

The irony grated. The only two things that could get Bobby’s attention, fast-moving objects and food, and I’d provided both. Well, maybe Frank could talk him out of–

“Yeah?” Bobby said, voice rising. “A junkie didn’t toss this out with the trash.”

Frank’s low whistle sounded ominous. What did they–

“I’ll be damned. Steven Black’s badge. Good eye, Bobby. Let’s move! You take the fire escape and see if you can spot her. I’ll take the squad car. Maybe I can circle around and cut her off.”

Damn. Dad’s badge must have fallen off its chain when I crashed into the wall. I thumped a fist against my thigh. This cloudburst of crappy luck just refused to end. I struggled to a standing position, swaying slightly to the rhythm of a dull, red drumbeat throbbing in my brain.

Aw, come on. Not now.

It figured. Migraines had always plagued me, but these were something else entirely—wracking, brutal spikes of pain that made my eyes water. They’d begun a little over a week ago, coming and going in short bursts, and somehow nastier each time. They were up to two or three a day now, and worse, there was no time to wait this one out: I had to move.

The fire escape clanged behind me, Bobby’s heavy boots thudding up its steps. Walcott grunted as he wedged his massive backside behind the wheel of the squad car and banged the door shut. His idiotic “Yeeee haw!” blasted through my earbuds like a nuclear bomb. I yanked them out with a grimace.

The whole wiretapping thing hadn’t gotten me as much as I’d hoped. The cops weren’t even investigating Dad’s murder. They didn’t know a damn thing.

I broke into a trot across the gravel-covered rooftop, the pounding in my skull keeping time with my feet as the edge of the building drew closer. From behind, Bobby shouted something. He must have made it to the roof.

Red splotches crept around the edges of my vision. I ignored them and dove for the next building over. Arcing through space, I caught snatches of Bobby’s breathless shouts.

“… Northbound, crossing 35th… set up a two block perimeter… can’t follow. I’ll maintain visual as long…”

I lost the rest as my feet skidded across the roof, converting my landing into a bone jarring belly flop. Strangely, the impact caused the migraine to ease up almost as quickly as it had begun. It made no sense, but I didn’t care. I squinted, trying to squeeze my muddled thoughts into order.

Frank had mentioned circling ahead. Bobby shouted something about setting up a two block perimeter. Two blocks? Not with only two of them. To surround two whole blocks they’d need more cops. A lot more. Gooseflesh rippled down my arms. What the hell was going on?

A sudden image of tribal beaters sprung to mind, hunters cooperating to herd a lion into an ambush. I glanced at the next rooftop, weighing my odds. That building fronted Parkland Ave, a four-lane road. Even the best parkour athlete in world couldn’t jump a gap like that. I’d have to drop to ground level, and they had to know it, too; that’s where their lion would die.

Sirens wailed from multiple directions. Crap, were there even more cops coming? Somewhere off to the side, Bobby shouted again, his voice echoing as if coming from a deep hole, but when I glanced behind, he wasn’t there.

It didn’t matter. I had to get out of the open. Maybe I could duck into a store, or disappear into the afternoon crowd. It was worth a try, but I needed to reach ground level, and fast. At the roof’s edge, salvation practically sprang out of the earth: A flag flapped lazily on a pole not ten feet away.

I stopped thinking and just jumped.

Tilting sideways, I caught the pole in both hands, swinging in a crazy spiral, palms burning as they scraped the rusty surface. I flopped to the ground, rolled a few feet, and came to a quivering halt. Not my best landing.

I hopped up and managed exactly two steps before a trio of cops appeared from nowhere, cutting me off. They spread in an arc, the one in the middle holding his hands out as if to settle a skittish deer.

I spun to the left.

About twenty yards away, a heavily breathing Bobby Kellog limped toward me, features caught halfway between triumph and admiration. He winked and snapped off a salute.

To the right, Frank Walcott leaned against his squad car, one hand resting suggestively on his holster, the other flipping me the bird. I was trapped, and he knew it.

Dead lion.

Slumping, I took a deep breath as the trio of cops converged on me. The one in the middle stopped and appraised my ruined clothes, eyes lingering on the blood. His hand twitched toward his cuffs, but something held him back.

He offered a not-so-reassuring smile, but when I didn’t return it, he shrugged and reached for my shoulder.

“Samantha Black? You’re coming with us.”

The post GNOSIS – Chapter 1 appeared first on Rick Hall.

October 2, 2018

The Writer’s Voice

The Writer’s Voice

You need to strengthen your voice.

This obnoxious sentence makes writers want to poke their own eyes out with an unsharpened pencil. An unassuming, simple sounding criticism, the words frustrate us, and for good reason. The obvious response, “okay, how do I fix that?” is invariably met with a shrug and an ambiguous, useless retort.

“It’s a matter of experience,” they tell us. Or “you just have to write until your voice emerges.” My personal favorite is “I can’t define it, but I know it when I read it.”

Yeah. Super helpful. Thanks so much.

As writers, we’re eager sponges, with a desperate urge to hone our skills. We rarely approve of our best efforts, and when we encounter criticism, we take it seriously. But what hope do we have when the people who point out the problem can’t even define it, let alone tell us how to fix it?

I’ve read plenty of blog posts, articles, and books on voice. Most fill the pages with endless contrasting examples of ‘good voice’ and ‘bad voice’. “See?” they proclaim. “Do it like this. Not like this.”

I’ll take it on faith that I’m dense, but this approach did nothing for me. The burning desire to improve remained, and seeing examples of ‘good voice’ was akin to showing a starving squirrel an oak tree surrounded by an electric fence.

What I needed was for someone to connect the dots, and no one could pull it off.

That’s when I decided to stop looking for other people to solve my problems, and do it myself.

To start, I had to set aside my frustration and admit that the vague advice I’d read on the subject of voice wasn’t without clues. The most important of these was “good voice is confident.” I started with that.

Unfortunately, the solemn wisdom didn’t extend much further than that. When offering advice on how to achieve this magical confidence, the ensuing suggestion was “you have to believe what your character is saying. It’s like method acting.”

Yeah. Writer here. Not an actor.

Nevertheless, I thought about it for a while and decided that maybe there was more there than what I saw at first glance. I turned to my favorite device: identifying a suitable model to compare it against. I asked myself “Who is confident?”

Well, leaders for starters. So why not look into leadership techniques, and see where that goes?

We’ve all read that the primary quality of intuitive leaders is a decisive, unshakeable belief in what they’re saying. Much like the advice offered above, the leader believes what they say.

With that as my starting point, I dove headfirst into the challenge, and happily, it took very little time to discover quite a few pearls of wisdom at the bottom of the uncertain sea called the Internet.

Luckily, there have been quite a few studies regarding the speaking style of leaders. Numerous articles pointed out that if one parses a leader’s words, a number of specific, quantifiable tactics emerge.

Don’t Equivocate. It’s okay to be judgmental

It’s shocking how often writers convince themselves that their protagonist is “only human”, and that it’s perfectly reasonable that they would experience moments of uncertainty. The problem is that readers don’t want this in their heroes. We all know that.

But do we, as writers, remain true to that premise? Look at your narrative. How often do you fill your writing with equivocations like:

must have, sort of, that kind of, a little, probably, he guessed, sometimes, she believed, she thought, perhaps, as far as he was concerned, most, a lot, might, can, could be, she assumed, reminded him of, tends to?

It’s all too easy to thoughtlessly sprinkle phrases like these into the narrative, introducing doubt and uncertainty through the eyes of the POV character. You need to jettison the caveats.

Imagine your character is a scientist researching a cure for cancer. Her peers are hot on the trail of a new form of gene therapy, but our erstwhile heroine is convinced they are chasing a red herring. In the narrative, you might write:

She didn’t think they had it right.

It’s a simple, direct sentence, and it reflects her genuine uncertainty, so what’s wrong with it? Well, everything if our readers want confidence. Heroic protagonists are manifestly sure of themselves, and the sentence above is far from decisive. Stronger would be:

They knew nothing, and people would die while they wasted their time.

The difference is stark. The narrator is confident, maybe even judgmental and arrogant. The bold statement, presented as fact, may prove right or wrong, but the narrator took a stand, and that’s what readers want. They want the hero who surges defiantly into the face of adversity and dissent.

The list of equivocation phrases above isn’t exhaustive, but if viewed through the lens of under-confidence, a clear pattern emerges, and armed thus, examples take on actual meaning.

Most reasonable people understood that what she was doing – walking outside during a hurricane – was dangerous.

transforms into:

We watched her sauntering up the street into the teeth of the storm, wondering how long it would take for a falling branch to crush her skull.

And

The little boat bobbed on the waves, reminding him of a child’s toy.

Easily becomes

The little boat bobbed on the waves, a bathtub toy in a dangerous ocean.

In these examples, the narrator shifts from making reasonable assumptions to stating bold, judgmental truths. From equivocation to decisiveness. From the caveat-laden language of reasonable people to the unshakeable declarations of a person with convictions. The changes are relatively subtle, but nonetheless important.

Comparing them, the former are the phrasings of uncertain followers, while the latter are the confident judgments of leaders.

Don’t Babble or Justify

Leaders are also succinct. They understand that excess words take longer to process and invite critics to pick at the details, and these things undermine the faith that followers have in them.

If you think about it, long explanations or justifications sound as if the speaker is unsure of themselves, and trying to talk themselves into something. Followers always want to believe that leaders know what they’re doing. That’s why people follow them.

Leaders speak in short, punchy, memorable chunks. They state simple truths and reach quick conclusions.

Writers often embed constant justifications into the narrative. They justify this by claiming that it is necessary in order for the reader to understand the character’s motivations.

Give your readers a little credit.

As an example of both babble and justification in one paragraph, consider:

Harvey’s finger hovered over the ‘buy’ button. There was a lot riding on this. Fifty thousand was only half of the total he’d embezzled from the company’s retirement account, but if Optronics split at the opening bell, he could slide the profits in through operating cash budget. No one needed to know. In less than a day, he could erase his crime. There would be no need to explain that the insurance hadn’t covered Lorraine’s medical bills. No need to explain his responsibilities as a husband and father. The risk had been worth it, and he’d do it again if he had to. But none of that mattered now. The worst was over, and all he had to do was take this one last risk.

I know a lot of writers who’d go much farther than that, endlessly rehashing information that had doubtless been provided in previous scenes, dragging out Harvey’s agonized decision. They wouldn’t be able to resist the temptation to sum it all up, like a lawyer’s closing statement.

But this kind of information dump is nearly always unnecessary. Even as an opening paragraph, when none of this is known to the reader, the pre-action babble serves no other purpose than to drag out the decisive moment. I’d much rather see:

Harvey stabbed the flashing green ‘buy’ button on his laptop’s touch screen, then wiped his hands on his pants and closed the lid. Accounts receivable was fifty thousand dollars lighter now, but if Optronics split tomorrow, he could replace the stolen funds without anyone noticing. And if it didn’t, well, no matter. Either way, Lorraine was out of danger now, recovering in St. Theresa’s Intensive Care Unit. If that cost him a few years in jail, he could live with it.

In the first example (125 words), there’s no action at all, but there’s a lot of navel-gazing babble. Harvey agonizes over the decision that he had no choice but to make, and the narrator pointlessly justifies it with back-story before pulling the trigger.

In the second example (81 words), the trigger is pulled in the first sentence. Harvey takes immediate, decisive action, and then concisely and matter-of-factly, the narration fills in the gaps.

Yes, sometimes a chain of logic is called for, but unless it’s absolutely necessary, kill the justifications. Your character should be certain. They should state plain, uncomplicated truths. The reader will keep up.

And frankly, we often enjoy those epiphany moments, when the hero’s actions strike us with one of those “Oh wow, that’s why she did that” moments. Don’t ruin your reader’s opportunity for discovery. Don’t undermine their faith in your protagonist. Give the readers a clear, decisive, simple image. Simple truths are viewed as self-evident, more believable by default.

Avoid Delayed Decisions

Much like indecision in word choice, there exists a kind of indecisiveness of action. Often, this takes the form of adverbs.

Hovering outside his hotel room, she reached tentatively for the doorknob.

Examples like this are tricky. Writers can come up with countless reasons why the POV character hesitates before opening any metaphorical door. And to be clear, many of these reasons are valid.

But as is often the case, too much of anything is a bad thing. You don’t want your characters constantly hesitating. Constantly agonizing over every tiny decision. When it’s necessary for dramatic tension, let them pause. But be vigilant. If you find your character doing this more than once every few chapters, you’re creating the same kind of uncertainty that poisons the narrative.

Heroes throw caution to the wind. They casually surge forward, ever ready to meet challenges head on. Don’t casually allow them to hesitate. Ever. When a character pauses before leaping into conflict, it should be a defining moment, nothing less.

Ignoring the flutter in her stomach, she willed a smirk onto her lips and swept into the room.

The woman in the first example is a timid school girl, afraid to commit to a decision. That’s a victim waiting to happen. Fine if it’s a secondary character, but only compelling in a protagonist in unusual circumstances.

The second example shows a decisive woman who won’t let nervousness get between her and whatever she’s after. That’s a heroine, and she forces readers to turn the page.

Understand that there’s a difference between the character and how the writer frames them. In both cases, the woman is nervous before entering the room. But the first example renders a character in uncertain, ambiguous language. The second shows much more clearly her state of mind. Voice isn’t the strength of character. It’s the strength of the description.

Root Out Verbs of Being

This is standard advice for writing and it’s also a component of voice. Verbs of being (is, are, was, were, be, been, being) are verbs that perform little function except to state the existence of a thing.

There’s nothing remotely interesting about simple existence. It conveys no nuance, no texture.

Consider a sentence like:

She was in the middle of the street, ignoring the rush hour traffic

A simple verb change and accompanying affect introduces much more interesting texture, and with it, a stronger voice.

She danced in the middle of the street, oblivious to the angry shouts and honking horns.

She planted herself in the middle of the street, shaking a fist at the rush hour traffic.

I won’t belabor this one, as there are countless good books and articles on passive voice, but I point it out because it’s clearly an impediment to strong voice.

Use Imagery, Metaphors, and Similes

Again, this is standard advice, but again I include it because it is also a component of voice.

Readers like to imagine. Everyone does. And nothing assists imagination more than a good metaphor. Metaphors and similes are a kind of shorthand. They not only provide a visualization for action, making it easier to understand, they also perform a more important function. They bring associations with them.

The point of a metaphor or simile is to use a small number of words to add a large amount of information.

Let’s say we compare an inquisitive person to a ferret.

Twitching his nose like an oversized ferret, he pounced into the room, rooting through the pile of clothes on the floor.

If you’ve ever owned a ferret, you know all about their insatiable, relentless curiosity. When a ferret sets its mind to locating and stealing a shiny object, almost nothing can stand in its way. By providing this association to the reader, we need only four extra words to add all of the instinctive, relentless attitude of nature’s most tenacious rodent into the character’s personality.

This type of imagery makes characters more recognizable. More memorable. And it is ineffably tied to voice.

Conclusion

Writers inevitably get much too wrapped up around the notion of plausibility and reality. In their zeal to represent realism, they forget that readers don’t actually want realism. They don’t. Readers want things that are larger than life. They want to live vicariously through characters that are driven and decisive. Readers want to know what it feels like to confidently stride into conflict, self-assured and prepared to brave the unknown.

As a writer, your language can either add to that goal or undermine it. When you undermine it, that’s what critics mean by a weak voice. Your writing doesn’t match the heroism of your character.

When you render a confident character with weak words, (or even when you render an under confident character with weak words), the result simply feels wrong. There are no grammatical errors. The language may be lyrical and poetic, but voice is more than that. It is the confident, almost heroic way that the writer decisively paints the character.

So in the end, the writer does need to be confident, just as the advice said. Paint your characters with a decisive brush, boldly stating what they are. Don’t hedge. Don’t equivocate. Don’t apologize.

Shamelessly tell us who they are.

That’s voice.

The post The Writer’s Voice appeared first on Rick Hall.

August 11, 2018

Down and Across

Down and Across

Arvin Ahmadi

I picked up Arvin Ahmadi’s book, Down and Across. a bit later than I usually do. I prefer to get the debut authors right when they first release, but it was different enough from my usual fare that I decided to give it a try.

So what’s the verdict? Buy it or not?

I’ll give that a qualified maybe.

Here’s the thing. This book has lots of things to recommend it, and lots of things that need a bit of work. We’ll go through them one at a time, and in the end, you might have to decide for yourself. I’ll start with the story concept, and then move on to the positives, and end with the negatives.

Story concept

Underachieving protagonist Scott Ferdowski is a typical teen with helicopter parents. They’re immigrants, and demand that he overachieves. He’s an introvert with low ambition, and doesn’t have it in him. He meets the archetypal wild child in college student Fiona Buchanan. She is the exuberant, hedonistic, live-in-the-moment type, and she takes Scott on an adventure to find himself.

Positives

One thing I’ll give Ahmadi, he creates unique and interesting characters. A lot of debut authors make the mistake of only giving personalities to the main characters, and everybody else is just a mindless clone with a purpose, and not much else. That’s not the case here. From the protagonist to Fiona, Cecily, and the rest, the characters a vivid and distinct. That always makes for potentially interesting interactions, when widely differing personalities collide with each other. Ahmadi handles this well, and that’s probably the biggest strength of the novel.

The dialog is another strength. Ahmadi creates plausible, readable teen-speak, yet still manages to keep his characters distinct in their speech idioms. It’s a neat trick, and on full display in Down and Across.

At times, Down and Across is intelligent, funny, and even occasionally moving. Ahmadi doesn’t produce heart-wrenching drama or gut busting laughter, or Confucian philosophy. It’s more toned down in all three areas. It’s quirky and succinct, solid in a spectrum of emotional content, but not exceptional. Despite the John Green comparisons, Ahmadi doesn’t reach that level.

The writing itself is strong, although there were a noticeable number of repeated phrases like “suddenly”, and “we laughed tremendously.” Not enough to damage the story at all, though.

The John Green comparisons in the Amazon ad were appropriate, although it’s no surprise that I think Ahmadi hasn’t yet reached the John Green level. Still, if you like that feel, then this book might be promising.

Negatives

Probably the single biggest negative, for me, what the thinness of the plot. It was more like a theme than a plot. If you read over the story concept above, it will sound familiar. Really familiar. It’s been done before relentlessly. For me, this novel had an odd, almost Seinfeld feel. You know, a very tactical television program about mothing. Down and Across is pretty much the angsty-teen-coming-of-age-quirky-drama version of Seinfeld. That’s the big reason I appended a caveat to my recommendation. If you prefer character interactions over plot, then this novel might be a good fit for you. But if the plot is important, if you want an author who keeps you guessing, then you won’t like Down and Out at all.

That last bit is another issue I had with this book. I’m in the camp that likes a feeling of discovery. I like characters that surprise me. I like the epiphany moments. I like saying to myself “Oh, man, why didn’t I see that coming? It was all there, and somehow, I missed it.” You don’t really get any of that with this book. The author is clear about what’s going on, dwells on it for brief periods of time, and then moves on.

The ending is yet another let-down (for me). In a standard story, the story goal is laid out early, and the protagonist pursues it throughout the story. In Down and Across, the ending involves solving a problem that didn’t actually exist at the start of the novel, and was created by the characters themselves just before solving it. IT left a very unsatisfied taste in this reader’s mouth.

Conclusion

With a mix of positives and negatives, this is a tough call. In general, I think it’s one of those books that readers will either love or hate. So under the assumption that you are, in fact, a fan of John Green (and possibly character-driven, Seinfeld-like, stories about nothing), then I’ll de-emphasize the negatives associated with those things.

That brings me to a rating of 4 stars.

The post Down and Across appeared first on Rick Hall.

August 5, 2018

The Nightmare of Moxie Gore

The Nightmare of Moxie Gore

By Jeremy Scott Ryan

As always, I’ll start my review with the point: my verdict on The Nightmare of Moxie Gore, Jeremy Ryan’s debut novel.

I. Freaking. LOVE. This. Book.

Decisive enough for you? I’ll state for the record that I’m not a huge fan of five star ratings, because something in my brain wants to say 100% is perfection, and nobody is perfect. Unfortunately, 4.99 stars sounds idiotic, so I’ll set aside my reservations and go with 5.

The Nightmare of Moxie Gore is charming book, equal parts snarky, surreal, and creepy. It’s short, listed as 209 pages on Amazon, but efficiently packs a respectably complete story into a small space. It’s the first book in what Mr. Ryan has titled The Pallbearer Prophecy, and if there was a pre-order option for book 2 on Amazon, I’d be clicking it already.

Moxie Gore is an unusual sixteen-year-old girl living in contemporary Massachusetts. Somewhat in the vein of Harry Potter, she is an outcast, both in the fact that she isn’t loved by family at home, and that even among the small paranormal organization known as The Order of Aldred, she is different from everyone else. Like Harry, she is a chronic outsider, with her nose pressed to the glass of life more often than not.

Also similar to Harry Potter, the world Moxie lives in is at times whimsical and fantastical. With a two-dimensional death train, handbags that are far deeper on the inside than the outside, self-animated maps that only work when viewed in one’s peripheral vision, cattle prods for herding ghosts, the JK Rowling influence is hard to miss. And easy to love.

But don’t let that fool you into thinking this is a Potter-knockoff. The Nightmare of Moxie Gore is edgier and darker, while still remaining firmly entrenched within the confines of Young Adult. Ryan’s characters are largely deceptive, and the reader is constantly second guessing where their loyalties lie.

The novel moves at a brisk pace and adheres to a solid structural model, even to the point where the classic midpoint contextual change happens at almost exactly the 50% mark. (no spoilers, but a single fact is presented at this point that totally changes Moxie’s view of everything.)

The book is well crafted with the perfect amount of introspection to provide Moxie with depth and plausibility, but not enough to cause the reader to get bored.

The supporting cast is littered with vibrant, interesting characters. Unlike typical debut authors, Ryan doesn’t neglect the minor characters. None fell flat. Again, this feels reminiscent of Rowling’s work, where even a bit-part bus driver named Stan Shunpike manages to leap off the page and steal a scene, Ryan leaves the reader wishing that every character had a bigger role.

If you put a gun to my head and demanded to hear a few negatives, I might grudgingly point at some scenes in the second half of Act 2, where Moxie enters a decidedly weird and surrealistic dream world. There were a few points where I felt like I’d lost my anchor, and the story ‘floated’ a bit. The dream scenes flashed by, each wildly different from its predecessor, and the result was somewhat dizzying. In this one area, I felt that Ryan perhaps went overboard with too many rapid-fire scenes, each perhaps too description-rich, and each so fundamentally different from the world to that point, that I stopped and blinked, saying to myself “Wait. What?”

But as I said at the start, no novel is perfect. This minor issue should in no way dissuade readers from plunking down a couple of dollars to buy a ticket to a fantastic world.

The Nightmare of Moxie Gore earns my five star rating.

The post The Nightmare of Moxie Gore appeared first on Rick Hall.

August 3, 2018

Gnosis Character Gadget

Subscribe

Here is a fun toy I developed for creating quick character thumbnails. Based on the Myers-Briggs personality types, you select an MBTI type from the dropdown list. Move the slider towards good or evil, and then click the Generate Random Character button. It will provide a bunch of information that is consistent with that character personality, along with examples of real people or fictional characters who demonstrate that type. if you don’t like the character, you don’t need to change anything. Just click the Generate Random Character button again, and it will swap out some of the affects, providing you with some different options. It’s useful if you want to create a character thumbnail without a lot of investment. (Note, this tool isn’t optimized for phone screens. Sorry.)

I used it to create the characters for my YA Urban Fantasy novel, Gnosis. Feel free to click on the image to the left to buy it on Amazon!

The post Gnosis Character Gadget appeared first on Rick Hall.

August 1, 2018

Sanctuary – Caryn Lix

Sanctuary

by Caryn Lix

Ok. I’m the type who doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to critique, but let me start by stating my conclusion first.

Is Sanctuary, Caryn Lix’s debut book, worth reading?

Yes, it is.

I had a number of issues with the book, which I’ll lay out in my review below. Some of them are quite noticeable, and they take the quality of the book down a notch. But even so, I enjoyed the read. Sanctuary is, seemingly, the start to a series, and I anticipate buying the next one when it comes out.

Caryn Lix is a debut author, and like anyone new to the craft, she will continue to improve and refine her style, but as a first effort this book is fun, engaging, and solid.

With that said, I’ll dive into a detailed critique, but I want to emphasize the comment above. As a whole, the book was worth reading. I enjoyed it, and I don’t regret the decision to buy it one bit.

Characters

The story’s main protagonist, Kenzie, is a fairly well rendered, typical angsty teenager. She’s plausibly tough, imperfect in a good way, reasonably believable, and likeable. The progression of her relationship with Cage loosely follows a sort of Stockholm Syndrome, evolving into genuine affection at a decent pace.

Cage, Kenzie’s romantic interest, is the typically misunderstood bad-guy-who-isn’t-really-a bad guy. In fact, he’s closer to a milk-drinking, boy-next-door type than the international criminal he’s supposed to be. He doesn’t have the hard edge we’d expect of someone who lived his life. With that said, he’s likable enough.

Other notable characters that were rendered fairly well were Mia, Alexei, mom, Rune, and maybe Matt.

But from there, character development ranges from fair all the way to nonexistent. There are numerous characters who have names, abilities, and purposes, who occupy noticeable roles, yet have very shallow, one-dimensional personalities. These include characters like Rita and Tyler.

Then there is a small army of characters who have names and a single purpose, but no personality at all; characters like Noah, Jonathan, and Reed.

These problems exist for several reasons, the first of which is because Lix haphazardly introduces too many characters early on. In the first nine pages, we are introduced to no less than nine characters. This makes it really tough to keep them all straight. Worse, three of those characters disappear almost immediately, never to return, and a fourth disappears from the story early on, only to return much, much later for a few pages, and then disappear from the story a second time. This is problematic, because as readers we have been trained to expect all the early characters to be important. When almost half of them are throwaways, we don’t realize this. We become distracted, wondering why those characters merited introduction at all.

Another character development issue stems from Lix’s tendency to continue introducing new characters almost until the very end of the novel, either to fill out the crowd with more bodies or because the story needs their special abilities. With no real time to interact in any meaningful way, these characters sometimes just act like “red shirts” in Star Trek. They exist simply to exist. Or to die.

Additionally, the occasional Deus Ex Machina rears its ugly head with characters like Reed. I won’t spoil anything, but if you read it, the minute you see Reed’s name you’ll know what I’m talking about. He’s a new character, introduced very late, but at exactly the right moment when his capabilities are essential to progress the story. That’s a little too much like “the butler did it” for my tastes.

Plot & Structure

Plot elements early on were relatively easy to anticipate. Lix uses the cliché of: “It’s an emergency. Wait, no it isn’t. LOL. Yes, it is, I tricked you.” It’s great when this works, but unfortunately, it didn’t.

As the story went on, I continued to correctly anticipate the plot. However, Ms. Lix did finally manage to get the hang of it 75% of the way through, and things began happening that surprised me. It’s fun when you can sense an author evolving throughout the course of writing the novel. It gives you faith that they’ll continue to grow over time.