Cathy Sultan's Blog, page 18

April 29, 2015

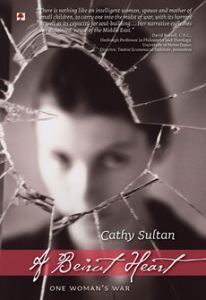

A LOYAL BEIRUT HEART

I think about dodging snipers and running into shelters, about aprons with bullet holes, and about rescuing my children from school. In my memory I can still see my fail daughter and her despair.

I think back to the time when we were hit by the rocket, to the bodies in the street and to poor Bachir, our newly elected president. \

I think about the frightened stork we tried to save, of the times when I was so depressed I nearly gave up hope; and I rejoice that I chose instead to enjoy life in all its incredible passion and beauty.

My husband and I now live on twelve acres just outside the city limits of Eau Claire, Wisconsin. I must confess that I am still something of a romantic, and I enjoy living among my most prized possessions from Beirut���the Roman artifacts, the Persian carpets, the Phoenician amphorae, our five hundred French comic books���all things which a dear friend was able to ship to use several years ago.

I cannot help that my heart still beats to the rhythms of a city which no longer exists. I have lovely friends in Eau Claire, for whom I still love to cook and entertain. And thanks to my new knees, I can dance again. There are no fancy nightclubs in Eau Claire, but my husband and I roll up a carpet, put on our LPs and pretend we are back at the Retro or the Caves du Roi in Beirut.

I still take a siesta in the middle of the day, and I still speak like a Lebanese, casually drifting from English to French or Arabic, depending on what I want to say or whichever comes first. In Beirut, I found my place to grow. My commitment to stay there through the war was a consequence of a deep love affair. I had married into a family which was for the most part loving and accepting, and it was exciting to wake up every day as a foreigner embraced by a Lebanese family. My heart is loyal: loyal to my wonderful husband and to our children who shared and survived the experience of war, and loyal to a country still in crisis. This is the kind of love which develops a loyal Beirut heart, one which never dissolves. My adopted country, that dysfunctional lover I���ve driven you mad talking about, may, sadly, never recover. A popular swell of nationalism and world opinion has set the occupying forces packing. But bombs are going off again, and politicians are being murdered so here we go again! I cannot go back there to live and rick my hard-won sanity, and I have finally accepted that. While there is sadness in this acceptance, I feel a sense of liberation in being able to acknowledge it at long last. With war finally cleaned out of me, my Beirut heart can enjoy, finally, the peacefulness of Eau Claire.

You may find my memoir interesting���A Beirut Heart: One Woman’s War��from Calumet Editions.

April 21, 2015

A STROLL THROUGH THE OLD CITY

It was market day on Saleh el Din Street. Peddlers Market���the area outside the Damascus Gate of the Old City in Jerusalem���was full of vendors selling everything from nightgowns and underwear to tennis shoes, scarves and plastic slippers. The steps leading down from the street were so congested I dared not look around unless I stopped in my tracks, and then I risked being pushed from behind by the throngs of people descending toward the Gate.

From the moment I walked into the Muslim Quarter through the Damascus Gate���one of the eight gates leading into the Old City���I felt as though I was stepping back into antiquity. The walls surrounding the Old City dated back more than 2,000 years. In a place which in ancient times must have smelled of cedar, musk, incense, and myrrh, it was easy to conjure up the image of women draped in bright reds and blues sitting along the cobblestone walkway hawking their pottery to Hebrews and Canaanites. The original water-delivery system to the Old City was still in use���an open gutter along either side of the narrow walkway called Al Wad Road. The Crusaders, who claimed Jerusalem as their capital for most of the 12th Century, built the massive stone walls lining both sides of the walkway.

Shops, crammed into every conceivable space along either side of Al Wad Road, were full of colorful local wares: exquisitely embroidered cloth in Palestinian motifs; unique Armenian artisan dinner dishes painted in browns, turquoise and blues; shelves of hand-painted pottery and glass jars, replicas of ancient Phoenician vases used to store precious oils and perfumes. For the leisurely stroller who wanted to treat himself to the mouth-watering taste of hot flat bread dusted with thyme and olive oil, or spicy grilled meat kabobs and spit-roasted chickens, he had to spend only a few shekels. And he only needed sit back at any of the numerous cafes along Al Wad Road , order a Turkish coffee, smoke a nargillas and marvel at the 15th Century Mamuluk architecture surrounding him.

Continuing through the Muslim Quarter, across the Via del Rosa, I came to a junction approximately twelve feet wide. If I turned left, I would have found myself not far from a door leading to the Dome of the Rock. If I continued straight, I could enter the Jewish Quarter and to my right were the Christian and Armenian Quarters. I turned left and walked into the Suq al-Qattanin (cotton market), a bustling covered bazaar with an arched tile roof at least a thousand years old. I strolled to the end of the bazaar, where I caught a close-up glimpse through an open door of the glittering, gold eight-sided Haram-al-Sharif (Dome of the Rock) on the Temple Mount. The Dome was centered over a sacred rock believed to be the place where Abraham was about to sacrifice his son, and from which Muhammad ascended into heaven. This magnificent piece of Islamic architecture���laced with intricate mosaics and bordered with tiles that bore quotations from the Quran���was built by Abd el-Malek in 691 CE. Abraham, David, Solomon and Jesus are said to have prayed at the Well of Souls in the downstairs level. The Al-Aqsa mosque, next to the Dome of the Rock, is Islam���s third holiest site after Mecca and Medina. It was built between 710 and 715 CE.

April 18, 2015

THE SYSTEM WAS RIGGED; EVERYONE KNEW IT

Andrew sat in the chair near the window and looked up. There they were: the unchanged, unchangeable stars. Tonight they felt like his only anchor in an otherwise dangerous and complex place he was only beginning to understand. He knew he was na��ve about the world in general and about his own government���s role in it. Until now, he���d lived his life as a smug, complacent American content in his profession, with the many rewards and benefits it gave him. Satisfied with what he read in newspapers and heard from politicians, he had closed his eyes to what was happening in the world around him. It was easy. None of it directly affected him. He had no family members in the armed forces. His country���s wars were in a part of the world he never thought he���d need or want to know or ever care about. He never asked what his government did, nor did he question the motives of powerful people who wielded influence over his political leaders. The system was rigged. It had been that way for decades. It never bothered him, until now.

At the time, he had questioned why his government went into Iraq and Afghanistan���why a leader who had been their ally for years had suddenly become the enemy and vilified by the mass media. Necessary regime change was the explanation. He did not understand that meant all-out war in Iraq and the destruction of that country, the mass murder of innocent civilians and the looting and destruction of a country���s cultural heritage.

The U.S. was a staunch ally of Israel. He had no reason to ever question that alliance. His parents had donated money to The Israel Fund to plant trees in that tiny nation right after its founding in 1948. He was taught that Israel was a democracy in a sea of hostile Arab countries hell-bent on its destruction. That it was the Arabs who were the trouble-makers with no integrity, not the Israelis. Now, after what he had learned, Andrew was no longer sure how he felt about his government���s destructive role in the Arab world and its support for Israel. He was full of questions about that country���s multiple invasions in Lebanon and his government���s decisions to take down Saddam Hussein. What was really behind such actions? It was not the weapons of mass destruction���everyone now knew that to be a lie. What about Syria? Was it true that the U.S. and its allies had decided that Syria should be dismantled, destroyed and put in the hands of a puppet amenable to U.S. dictates? Isn���t that what they had tried unsuccessfully to do in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya? It is not true that such actions, if repeated often enough, will eventually erode the global mechanism that strives to maintain stability and security through a balance of power based on legitimacy and responsible behavior? And if that���s lost, what���s left but a few powerful nations and wealthy individuals ruling and determining policy for their own greedy wants?

Excerpt from The Syrian

April 7, 2015

APRONS WITH BULLET HOLES

The Syrians have shelled our neighborhood for three days.

After the fighting we return to our apartment to find the windows shattered as usual. I want to sweep up the glass so I go to the kitchen to get my apron and broom. The apron, a long fuchsia one coated with plastic, hangs on its hook behind the kitchen door. As I reach for it I notice a hole in the middle. I put my finger through the hole and into the splintered wood of the oak door. On the floor nearby, mangled and hardly looking like a bullet at all, lies a three-inch machine gun slug. Across the room I find a round hole in the left hand corner of the window. The bullet ricocheted off the white tile in front of the sink and passed through my apron and the door before falling alongside our daughter���s Barbie kitchen set. Nayla often plays there with her pans and utensils spread around her, imitating me as I cook. Our son Naim pushes past me and picks up the bullet, saying, ���For my collection!���

I walk to the window and poke my index finger through the hole. In my imagination I can see the bullet entering my back as I stand at the sink. I can feel myself lying on the kitchen floor unable to move, gasping for air, and I can hear the screams of my family gradually fading around me.

My husband slips his hand around my waist to steady me. He does not need to say a word. I know he is thinking the same thing: once again, we were lucky.

And still there is no talk of leaving Beirut.

I now live in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where aprons hang safely on hooks and bullets rarely shatter kitchen doors. I returned to American in 1984, eight years into Beirut���s civil war. While I have come to appreciate the tranquil country living of Wisconsin, after thirty years I still anticipate my bi-annual trips to Beirut with the eagerness of a woman about to visit her charming old lover. And I am never disappointed. I delight in the city���s warm embrace. I delight in walking the streets, looking at sights and listening to the sounds of a community rebuilding itself. I love the dinner parties, the elegant lunches with friends at a newly renovated Phoenicia Hotel and catching up on the local gossip over great food and local wines. I always intended to move back to Beirut and grow old alongside these same friends. But after all the years in Eau Claire it is hard to imagine going back to a city which has been stalled in its development by fifteen years of civil war.

The Beirut I carry in my heart is the prosperous city of the late sixties-early seventies with its mansions, city parks, ancient souks, its bougainvillea, wisteria, its eucalyptus-lined boulevards���a place that no longer exists.

It was devastating to leave Beirut. The city had worked its way into my soul as great lovers do. Of course what I mean by the city is the people, the culture, the history, and the gracious Lebanese way of doing things. After all this time my heart still beats to the daily rhythms of vibrant, chaotic Beirut. I tell people I cannot help myself but the truth is I do not want to let it go.

April 6, 2015

THE BUILDING SHOOK AND THE CHANDELIER TINKLED

It was a Wednesday, a perfect day in late March after the long rainy cool months of January and February, the kind of day when you felt lucky to be alive. We had all the windows open and a light breeze was blowing in from the sea.

As I was putting the finishing touches on the hors d���oeuvres, I heard a neighbor playing a Coleman Hawkins tune. When that man played his jazz saxophone I could hardly keep my feet still. I was swaying to the beat when Michel walked into the kitchen, took hold of my outstretched arms and we began to dance a slow swing. When Myrna, one of our lunch guests, heard us laughing she came and stood near the door.

As Michel dipped me toward the floor she shouted over her right shoulder, ���Children, come see your parents. They are dancing. I think it���s������

In the middle of her sentence everything shook and the chandelier in the dining room began to tinkle. We were not sure whether the mortar had landed or taken off from the nearby field where our local militiamen were positioned. We looked at each other and I distinctly remember everyone silently deciding to ignore the explosion.

���Come on, then,��� I said. ���Let���s go and eat this wonderful food.���

I put the hors d���oeuvres, an assortment of duck and rabbit pat�� and smoked salmon, on the table alongside a platter of grilled shrimp with aioli and a large bowl of green salad. Everyone served themselves while Michel opened a properly chilled bottle of white wine.

There was another muffled noise. I glanced up at the chandelier. It did not move. We keep eating.

���To your health,��� I said, raising my glass.

���Sahah,��� Michel echoed as we drank and smiled at each other over our glasses.

Moments later, an explosion shook the building. Myrna dropped her fork on the plate. ���Oh my God,��� she said. ���What���s going on?���

���Nothing,��� said her husband, Tony, rolling his eyes. ���Nothing���s the matter. Just let me eat these wonderful shrimp.���

This time the whiz from the rockets grew shriller; they were getting closer. I caught my son looking at me. I knew I should react but in that brief second I refused to let the war bully me, enough time for Tony to stuff more shrimp into his mouth, before I finally reacted. When I stood so did Myrna, overturning her chair.

When our militiamen in the field next door began firing, Tony jumped to his feet.

���Come on, Myrna, we���d better leave. Damn shame, all that shrimp I could have eaten.���

���I���ll see you to your car,��� said Michel.

The incoming rockets were getting closer. I took the children in the corridor and we squatted down in the corner near the front door. For a second I thought of taking them into the stairwell, but when I opened the door and saw the neighbors rushing down the stairs in panic, trying to get to lower ground, I decided against it. Michel returned just then and agreed.

The first rocket landed nearby; the second was even closer. Michel laid his body over the children just as the third rocket hit the building. Glass shattered. We did not dare lift our heads to see where but I felt something sharp prick the back of my right leg. I put my hand to my calf. When I brought it back my fingers were bloody.

Everything went quiet.

There was something very welcoming in the unexpected abrupt stillness after so much noise.

Michel stood and helped me to my feet. We insisted the children remain where they were. We waited several minutes before we ventured into the dining/living room. The rocket had torn an opening about fifteen feet in diameter between our fifth floor apartment and our neighbor below. The wall air conditioner had been blown out of its brackets and flung across the living room. Shrapnel and crushed mortar from the front wall cluttered the floor. Michel motioned to me from the balcony just off the dining room. He pointed to the street below. A few dozen people had gathered around three dead bodies. The man was face down, his legs completely unspoiled down to the crease in his trousers, his head a mangled mess. Next to him was a woman drenched in blood.

For a brief second I thought of Myrna and Tony. The third was a little boy. A man rushed out of the apartment building in front of ours and pushed his way through the crowd. He walked toward the child and fell to his knees. The child, about five or six, looked as if he was asleep. The man lifted the boy into his arms. Two men standing nearby helped him to his feet. He pressed the child to his chest and tenderly kissed his forehead. He staggered, took a few steps then stopped. Sobbing, he looked up. He lifted the boy���s body and asked, ���Why God?��� The crowd parted to let him pass. They watched as the young father and son walked away.

April 2, 2015

WE JUST WANT TO LEAD NORMAL LIVES

You are almost sixteen years old. You have lived your whole lives under Israeli occupation. How do you feel about this?

“We are always frightened. We live in fear of being bombed, of seeing tanks in our neighborhoods and soldiers roaming our streets imposing curfews. It’s awful.”

Do you relax when you are around your friends?

“No, all we manage to do is talk about the occupation, about whose house was demolished, or who was wounded. At our age, we are supposed to be enjoying ourselves. We are, after all, still children. I have an eight-year-old sister. She should be growing up in a happy environment. All she knows is war and destruction. All we want is an end to the occupation. We want to be able to travel freely around Palestine, lead normal lives. Right now, we cannot even leave Ramallah. I can’t visit my grandmother in the next village. We missed my uncle’s wedding two weeks ago because we could not get a travel permit. Any time we want to leave, we have to apply for a permit. The Israelis take their time and in the end they deny us permission to leave.

“I know there are many good Israelis who do not think badly of Palestinians. However, there are many who abuse their religion. They think it is all right to kill Palestinians and steal their land. Judaism, like any other religion, is a religion of God, and God said, ‘Thou shall not kill.’ So I have to wonder if those Israelis practice their religion. If they did, they would not act like this toward us. They claim that because they are Jewish, they are entitled to this land. They call themselves the ‘Chosen People,’ but God loves everyone—Muslims, Christians and Jews equally. So, no one is special. We are all equal in His eyes.

“Just yesterday, Israeli settlers attacked some Palestinians in a nearby village and burned all their olive trees. They were not punished. No soldiers came and hauled them off to jail. Does the whole world believe they are the Chosen People and can do what they want to us? Why does no one take our side? When we commit acts of violence, we are called terrorists. When they invade our villages and destroy our property, it is called retaliation, for what I don’t know since they were the ones attacking. And if it’s not retaliation, it’s an act of self-defense.”

If the three of you were in charge of the Palestinian Authority, what would you do to implement peace?

“I would forget about Jerusalem, boundaries, the right of return, and just be one nation. We are all brothers and sisters, all from one family. Forget the leaders, the generals. All they ever want is war.

“I am certain many Israeli children have the same feelings, the same imagination of life, as it can and should be. We’ll talk to them. They’ll understand that we can, that it is possible, to live together. Right now, young Israelis live healthy childhoods. They go to sports events, attend parties and play outdoors. All we do is wake up, go to school, return home and listen to machine gun fire, to Apache helicopter gunships firing missiles, and tanks rolling down our streets. We cannot sleep. Our grades are dropping because we cannot concentrate on our studies. This is our life, and it affects us in horrible ways. Most of us have yellow skin and black circles under our eyes. We feel sick all the time. We have been deprived of our childhoods. This is not a happy time for us.”

WE JUST WANT TO LEAD NORMAL LIVES

��I interviewed three teenage girls in a high school in Ramallah, West Bank. They are intelligent and inquisitive. The speak Arabic, French and English fluently. They are restless and scared. More than anything, they want to lead normal lives

You are almost sixteen years old. You have lived your whole lives under Israeli occupation. How do you feel about this?

���We are always frightened. We live in fear of being bombed, of seeing tanks in our neighborhoods and soldiers roaming our streets imposing curfews. ��It���s awful.���

Do you relax when you are around your friends?

���No, all we manage to do is talk about the occupation, about whose house was demolished, or who was wounded. At our age, we are supposed to be enjoying ourselves. We are, after all, still children. I have an eight-year-old sister. She should be growing up in a happy environment. All she knows is war and destruction. All we want is an end to the occupation. We want to be able to travel freely around Palestine, lead normal lives. Right now, we cannot even leave Ramallah. I can���t visit my grandmother in the next village. We missed my uncle���s wedding two weeks ago because we could not get a travel permit. Any time we want to leave, we have to apply for a permit. The Israelis take their time and in the end they deny us permission to leave.

���I know there are many good Israelis who do not think badly of Palestinians. However, there are many who abuse their religion. They think it is all right to kill Palestinians and steal their land. Judaism, like any other religion, is a religion of God, and God said, ���Thou shall not kill.��� So I have to wonder if those Israelis practice their religion. If they did, they would not act like this toward us. They claim that because they are Jewish, they are entitled to this land. They call themselves the ���Chosen People,��� but God loves everyone���Muslims, Christians and Jews equally. So, no one is special. We are all equal in His eyes.

���Just yesterday, Israeli settlers attacked some Palestinians in a nearby village and burned all their olive trees. They weren���t punished. No soldiers came and hauled them off to jail. Does the whole world believe they are the Chosen People and can do what they want to us? Why does no one take our side? When we commit acts of violence, we are called terrorists. When they invade our villages and destroy our property, it is called retaliation, for what I don���t know since they were the ones attacking. And if it���s not retaliation, it���s an act of self-defense.���

If the three of you were in charge of the Palestinian Authority, what would you do to implement peace?

���I would forget about Jerusalem, boundaries, the right of return, and just be one nation. We are all brothers and sisters, all from one family.�� Forget the leaders, the generals. All they ever want is war

“I am certain many Israeli children have the same feelings, the same imagination of life, as it can and should be. We���ll talk to them. They���ll understand that we can, that it is possible, to live together. Right now, young Israelis live healthy childhoods. They go to sports events, attend parties and play outdoors. All we do is wake up, go to school, return home and listen to machine gun fire, to Apache helicopter gunships firing missiles, and tanks rolling down our streets. We cannot sleep. Our grades are dropping because we cannot concentrate on our studies. This is our life, and it affects us in horrible ways. Most of us have yellow skin and black circles under our eyes. We feel sick all the time. We have been deprived of our childhoods. This is not a happy time for us.���

March 28, 2015

ONE BATTLE, TWO PERSPECTIVES, PART TWO

������������������������������ Our unit was ordered into South Lebanon. I���m not supposed to talk about my feelings because an Israeli Defense Forces soldier is tough and is supposed to always be battle ready. But this time when I crossed the Lebanese border my heart sank into my stomach. I lost my best friend to one of Hezbollah���s roadside bombs in 2000 shortly before we withdrew and the last thing I ever wanted to do was return to this rugged, rocky death trap of a country, where Hezbollah fighters knew every shrub and rock formation and could have been hiding anywhere. And if rumors were correct, they now had some of the most sophisticated weaponry in the world. Alright, I���ll say it: I felt like I was walking to my death.

There were other unsettling things too about this particular war which added to my anxiety. Rumors abounded about reserve units being sent to the front without proper training. These were the guys who were supposed to back us up. And there���s another thing that didn���t bode well with a lot of us. Our Air Force had already spent two weeks carpet bombing the south without much success. What the hell were we supposed to be able to accomplish?

So there I was marching toward Bint Jbeil, a small village less than three miles from the Israeli border. From a distance it looked like a lovely place surrounded by wildflowers even in the heat of summer. In some other life I might have been walking to a neighbor���s garden party.

We were some minutes behind an advance patrol up ahead. We were approaching the outskirts of the village when we heard shots and explosions. It was obvious our soldiers up ahead were taking hits but there was nothing we could do. I ran inside a building and up to the second floor to try to locate the source of fire. Hezbollah had eyes everywhere. They were watching our every move and like idiots we walked right into their trap. I didn���t have time to sneak a look outside when a missile hit the house. In the momentary stillness after the explosion, I could hear our radio operator on the ground floor calling in our location and asking for help. I was relieved but before I could cross the room to the stairs a second missile exploded within feet of where I was standing. The blast knocked me up against the wall. My chest and arm got sprayed with shrapnel. I was momentarily blinded by a bright light before the room filled with smoke. I had difficulty breathing. I wanted to cough but when I tried I felt excruciating pain across my chest. And when I saw the gaping holes in my arm I almost passed out. I learned later that the metal shards had broken multiple bones in each arm. The medic in our unit tended to my wounds as best he could and taped up my arms. In the meantime we learned that the helicopter couldn���t get in close enough to evacuate us so we had to find a way to get closer to the border. I���m not sure how my buddies managed. All I remember is leaning on two strong shoulders. I was told repeatedly to keep my feet moving until we got to a point where we could safely board the helicopter back to Haifa.

All these months later do I regret having gone into Lebanon? Of course not! I love my country and we needed to fight this conflict to secure our northern border. But where are we as a nation now that the war has ended; are we more secure? Did we achieve our goal of destroying Hezbollah? I am young and don���t want to spend my whole life preparing for and fighting wars. In Israel we have a war mentality. We never seem to talk peace. It is as if saying that word is being disloyal to the State. I���m ready to live in peace with my neighbor. I think Hezbollah would do the same given the choice. Why aren���t our leaders willing to take the leap?

As I said earlier, I am no stranger to Lebanon but this time around Hezbollah was using a broad range of anti-tank missiles. Back in the ���80s, when I last encountered them, they were a militia. Now, they are a full-fledged army trained and equipped by Iran. But then, we���re equipped by the US so what���s the difference. In this war they drew us in like bees to honey and then pounded us almost to death. In the end, it was their territory they are defending. We would have done the same if someone had invaded our country and tried to take our land.

ONE BATTLE, TWO PERSPECTIVES, PART ONE

ONE BATTLE, TWO PERSPECTIVES, PART ONE

������������������������������ I am from Bint Jbeil, a village three miles north of the Israeli border. According to my grandfather our hilltop village overlooking northern Israel was established by the Phoenicians thousands of years ago when they migrated from Jbeil (Byblos), north of what is today Beirut. Bint Jbeil, by the way, means ���Daughters of Byblos.��� And did you know that the word ���Bible��� comes from Byblos?

Bint Jbeil is called the capital of Hezbollah. It is unfair, in my opinion, to refer to it as a Hezbollah stronghold, as if this was a crime, without fully understanding why and how all of South Lebanon, and Bint Jbeil in particular, became a place of resistance. For twenty years we lived under Israeli occupation, that is to say, Israeli occupation of Lebanese land, approximately fifteen percent of Lebanon.

I remember the exact moment I decided to join the resistance movement. I was fifteen years old. The year was 1985. My father was herding his cows when Israeli troops entered Bint Jbeil. They came into his field and shot him in the head without any provocation. He was not even carrying a gun. He was simply in his village on his own land in South Lebanon, tending his cows.

Because I was young and agile I was one of several young men assigned to observe Israeli troop movement. I did nothing else. Wherever they were I found a way to sneak up close enough to watch and mentally record everything they did. When they arose in the morning; what they ate for breakfast; where they carried out their patrols; how many soldiers participated and in which direction they traveled. I vividly remember one particular mission. It was a challenge because I had to carry it out alone. At the same time I felt privileged to be asked to undertake such a difficult task. It was crucial at this particular moment in time that we know everything the Israelis were doing and when and where they were doing it. I stood in a cold stream south of the village, hidden in brush, not moving, for three days. When it was safe to move so as to report what I had observed, I couldn���t walk. My feet were frostbitten from the freezing water so I crawled back to the village to give my report. I was in terrible pain but I didn���t care. I was willing to die if necessary to rid my village of Israeli soldiers. My strength came from the brave people of Bint Jbeil who abhorred injustice. It was not something any of them practiced toward their neighbors and they believed that no one should act unjustly toward them. But more than anything they held a deep moral certainly of what was fair and right.

I will never forget the battle of Bint Jbeil. When the Israeli troops entered they probably assumed they were entering a deserted village because there was no visible sign of life. We watched the soldiers enter the village. We knew ahead of time from which direction they would be entering. As I said before, one of our greatest strengths was that we knew everything about them and they seemingly knew so little about us. When they came into the empty marketplace we ambushed them from three sides. I was in no position to know how many people were left in the village when the battle began but I can tell you that before it ended many of them suddenly appeared with their machine guns and rifles and began firing on the soldiers. They were mad. The previous two days Israeli war planes had destroyed much of their village. They fought to defend what was left and were prepared to die if necessary. This energy created a powerful force, one that eventually drove Israeli troops from our village and the whole of South Lebanon.

March 22, 2015

TUWANI

Tuwani is a village in the southern hills of Hebron in the West Bank. It has a population of some 175 people, most of whom are either shepherds or farmers, who live in cave-like structures. Their village is important because it not only has the only school for the region, serving some 100 children, but it also has the only medical clinic and grocery store. The village had a mosque but it was bulldozed by the Israeli Army. The home of the mayor was also bulldozed and the school has a demolition order hanging over its head. The village has no water, electric power or telephone lines. An oil generator provides electricity for the houses four hours a night and their only water supply comes from two wells outside the village.

Surrounding Tuwani on either side are two illegal Israeli settlements whose extremist residents belong to the national-religious movement. One of the most dramatic consequences of the settlement expansion in this region, particularly from an outpost of settlers located some 500 meters from Tuwani, is the risk children must take to get to and from school, a risk caused by settler violence.

Alex was part of the Christian Peace Maker Team whose members stand with Palestinians and Israeli peace groups engaged in nonviolent opposition to Israeli military occupation. Since 2004 Christian Peace Maker Teams have escorted Palestinian school children to and from school in Tuwani. Alex’s mission each day was to accompany grade school children from the neighboring villages some two to three kilometers away to Tuwani and to safeguard them from settler attacks. Despite the ever-present threat of harassment, of being pelted with stones and chains, the children were eager to learn and happy to attend school. On the side of their small school-house they painted a mural depicting happy images and smiling faces.

“When I see these children so intent on learning, so willing to risk their lives each day, my sense of despair eases slightly,” said Alex, who had been attacked and severely beaten a number of times.

The city of Hebron is a half hour north of Tuwani. Tariq was our host during our two-day stay there. His father had died eight years ago but because he was buried in a part of town now off-limits to Palestinians Tariq was denied permission to visit his father’s grave. When he told us this, we collectively said, “We will escort you past the Israeli soldiers so that you can visit your father’s grave.” As internationals we knew the soldiers would not dare stop us. We marched up a deserted street of boarded up Palestinian stores, all 13 of us, past heavily armed Israeli troops and slipped under the barbed wire surrounding the cemetery. Tariq, accompanied by three of the men in our group, knelt beside his father’s grave and paid his respects. After he had prayed, we retreated en mass down the deserted street back to our bus.

I came away from my two-week stay in Israel/Palestine with more questions than answers. In the case of the Palestinians how does a popular upswing of democratic thinking ever take hold against a backdrop of such a brutal Israeli occupation? In America how does the majority regain its voice and convert a “clash of civilizations” mindset into an urgently needed “dialogue of civilizations” so as to resolve this festering crisis?

I also came away humbled in the realization that I have much to learn about patience, fortitude, forgiveness and hope if I ever aspire to walk in the footsteps of the Palestinians, most of whom practice nonviolent resistance, who have learned from the likes of the great civil rights leader, Congressman John Lewis, that hatred is too heavy a burden to carry.