Jennifer Crusie's Blog, page 230

June 8, 2016

AIBC: Going Postal: Theme, Part Two

Theme should always be handled lightly, which is why the best books often inspire theme arguments. I think there are two possible themes here, but I also think that one is arguably more of a Discworld theme, and the second is the real heart of Going Postal, the basic statement it makes about the human condition.

1. “No practical definition of freedom would be complete without the freedom to take the consequences.” [Vetinari pg 46 digital]

There’s a running theme throughout the Discworld novels that actions always have consequences. Even magic, the universal get-out-of-jail-free card, will come back to bite you:

“You could wave a wand and get twinkly stars and a fresh-baked loaf. You could make fish jump out of the sea already cooked. And then, somewhere, somehow, magic would present its bill, which was always more than you could afford.”[pg 411]

So Alfred Spangler the con man is hanged, and Moist Von Lipwig is offered the choice between the post office and Door Number Two, and Adora Belle Dearheart gives up believing in love and then meets Moist, and Reacher Gilt reaches and reaches and reaches, sure in the knowledge that there are no consequences for him, and then his bill is presented. It’s one of the underlying tenets of both life and fiction: There is no free lunch.

I think that’s too vague, too broad to be the theme here, but that could be because I love the second theme so much that I’ve built my career on it:

“Words are important. And when there is a critical mass of them, they change the nature of the universe.”

I love this sentence: you can unpack it so many ways. But in this book, I love the way Pratchett makes this idea flesh, or at least paper, by having the letters whisper to Moist:

“Every undelivered message is a piece of space-time that lacks another end, a little bundle of effort and emotion, floating freely. Pack millions of them together and they do what letters are meant to do. They communicate and change the nature of events. When there’s enough of them, they distort the universe around them.”

I love the way the letters literally sweep over Moist . . .

. . . and the way he sees Reacher Gilt’s counterattack in the newspaper as a crime against words:

“It was garbage, but it had been cooked by an expert. Oh, yes. You had to admire the way perfectly innocent words were mugged, ravished, stripped of all true meaning and decency, and then sent to walk the gutter for Reacher Gilt, although ‘synergistically’ had probably been a whore from the start . . . . The Times reporter had made an effort, but nothing short of a stampede could have stopped Reacher Gilt in his crazed assault on the meaning of meaning . . . . Moist felt acid rise in his throat until he could spit lacework in a sheet of steel.” [pg. 808]

Here’s the thing about theme: If you hit it too hard, your story breaks. As Sam Goldwyn never said,”If you’ve got a message, send an e-mail.” The theme should lurk below the surface, pulling everything together, although in Pratchett’s omniscient fantasy novels it occasionally lifts its head and speaks its name. Its real strength is infusing the action in the story with meaning. There are a million ways that Moist could have defeated Reacher Gilt including just shooting him (except the gonne has been outlawed in Ankh Morpork, see Men at Arms), but instead he brings him down with words. Inspired by the whispering letters, Moist uses words to restore the post office and bring real competition to Gilt, words to rally the staff when Gilt’s arson seems to have defeated them, words to lure Gilt into a competition that Moist can’t win but that everyone believes he will. And in the end, he sends words out over the Trunk lines that destroy his enemy. Reacher Gilt whores words out to distort the universe; Moist sends words out to deliver justice and restore the universe. It’s no accident that Going Postal‘s hero is a con man: if you’re writing a book dedicated to the idea that words shape reality, what better hero than a man whose stock-in-trade is reshaping reality and whose sharpest weapon is his way with words?

The post AIBC: Going Postal: Theme, Part Two appeared first on Argh Ink.

June 7, 2016

AIBC: Going Postal: Character, Part Two

So I’m still figuring out the best way to do a book club here. I started with very open posts, but I’d like to also try starting points that are more focused. So let’s look at the characters of Moist, Adora Belle, and Reacher.

OUR PROTAGONIST: MOIST VON LIPWIG

Moist is our protagonist, a con man and a thief, who’s trapped into bringing the Post Office back from the dead by the tyrant Vetinari. As others have mentioned, it’s hard to make a bad guy the protagonist (Nate Ford notwithstanding), but looking at Moist from the beginning, I found him fascinating because he’s smart, he has a great sense of humor, and he never ever quits. I love this explanation of Moist’s choice of targets:

“If you did fool an honest man, he complained to the Watch, and these days they were harder to buy off. Fooling dishonest men was a lot safer and, somehow, more sporting. And, of course, there were so many more of them. You hardly had to aim.” (pg 53, digital edition).

His introduction is scraping away at the mortar in the bricks in his cell with a dented and bent spoon, only to pull out the brick and find another shiny new spoon and another brick wall. He’s annoyed, but he doesn’t let that change his dealings with his jailers: Moist is always charming. Then he has a nice back and forth with the hangman, offering up his last words with grace: “I commend my soul to any god that can find it.” And he’s hanged. Then he wakes up in the tyrant’s office and is offered a choice: he can take over the defunct post office or leave by the door behind him. Moist goes to the door, opens it and sees that “there was nothing beyond, and that included a floor. In the manner of one who is going to try all possibilities, he took the remnant of the spoon out of his pocket and let it drop. It was quite a long time before he heard the jingle.”

And that’s Moist, a man who lives by his wit and his wits, which fortunately are very sharp. He goes through the usual Hero’s Refusal of Call and then ends up at Post Office, a ruin of a place where the undelivered letters whisper to him and his staff is a very old man with peculiar medical beliefs and a very young man who collects pins and has his Little Moments. Having established Moist as an unregenerate scammer, Pratchett drops him into a nightmare he can’t escape from and then turns the screws, which is the best thing you can do for a protagonist.

In this case, it’s the letters, whispering to him, that shift his view of reality, seeping into his brain with the insistence that they must be delivered. As Moist plays the game of pretending to be the postmaster, the game plays him and he becomes the postmaster, drawing to him people who believe in him, creating in him a need to be believed in. Pratchett does a masterful job of making Moist’s talents and motivations one gear in his story that turns the gear of the whispering letters that in turn moves Moist to begin to reclaim the post office, that turns the gear of the post office people who rally to him, that turns Moist again to great heights . . . Moist ends up where he ends up because he’s Moist, but he’s not the same Moist that he was in the beginning. That is, who he is as a character determines what he does, and what he does changes his character so that he becomes someone new at the end, when he realizes this:

“I’m not Reacher Gilt. That’s sort of important. Some people might say there’s not a lot of difference, but I can see it from where I stand it’s there.” [pg 858]

That’s why in the end when he makes his great suicidal gesture, it was inevitable from the start:

“Moist couldn’t have stopped himself now for hard money. This was where his soul lived: dancing on an avalanche, making the world up as he went along, reaching into people’s ears and changing their minds. [pg. 933]

He’s still the Moist he was in the beginning (well, in the beginning he was Alfred Spangler), it’s that now he’s scamming the bad guy. Sometimes bad guys DO make the best good guys.

OUR LOVE INTEREST: ADORA BELLE DEARHEART

A love interest in a story is almost always there to help characterize the protagonist (unless it’s a romance, of course). In this case, she’s Adora Belle, the least romantic heroine of all time: “There was a definite feel about Adora Belle Dearheart that a lid was only barely holding down an entire womanful of anger.” [pg. 176]. Adora Belle is the perfect match for Moist because she can see right through him, the Discworld equivalent of “You get me.” I really hate that one–I have worth because I understand you? Gee, thanks–but in this case, because Moist has built his entire personality on people NOT knowing him, it’s very effective. Add to that the fact that Adora Belle never needs rescued: there’s that lovely scene in the Broken Drum where she calmly puts down the masher before Moist can do it and get his face shoved in, thereby rescuing herself and Moist. She also has an important role to play in the plot since Gilt destroyed her family when he took over the Trunk, but mostly, she’s there for Moist to fall in love with:

“You hardly know me, and yet you invited me out on a date,” said Miss Dearheart. “Why?”

Because you called me a phony, Moist thought. You saw through me straight away. Because you didn’t nail my head to the door with your crossbow. Because you have no small talk. Because I’d like to get to know you better, even though it would be like smooching an ashtray. Because I wonder if you could put into the rest of your life the passion you put into smoking a cigarette. In defiance of Miss Maccalariat, I’d like to commit hanky-panky with you, Miss Adora Belle Dearheart . . . well, certainly some hanky, and possibly panky when we get to know each other better. I’d like to know as much about your soul as you know about mine . . .

He said: “Because I hardly know you.”

“If it comes to that, I hardly know you, either,” said Miss Dearheart.

“I’m rather banking on that,” said Moist.

The people we associate with characterize us. (For proof of that, see the current hell Republican politicians are in trying to disavow Donald Trump’s racist rhetoric while still supporting the nominee.) The fact that Moist falls madly in love with Adora Belle tells us more about Moist than it does about her; the fact that she later falls for Moist tells us a lot about what’s lurking under that angry exterior.

But mostly, I just love Adora Belle, a woman who is not blackmailed into yes when her sometimes date proposes in front of a cheering crowd, a woman who works to save golems because they need somebody to fight for them, a woman whose mother weeps in the kitchen because she finally has a gentleman caller (using the word “gentleman” loosely), a woman who chainsmokes and wears severe clothing and makes both of those things madly sexy, at least to Our Hero, without even trying. Adora Belle, like Agent Carter, knows her worth, and Moist is going to have to earn her.

OUR ANTAGONIST: REACHER GILT

Reacher is a doppleganger antagonist: He and Moist are the same person at the beginning of the book, albeit Reacher is working on a much larger scale, as commenters have pointed out earlier this week. Moist’s evaluation of him not only describes him, it characterizes Moist:

“Moist had worked hard at his profession and considered himself pretty good at it, but if he had been wearing his hat, he would have taking it off right now. He was in the presence of a master. He could feel it in the hand, see it in that one commanding eye. Were things otherwise, he would have humbly begged to be taken on as an apprentice, scrub the man’s floors, cook his food, just to sit a the feet of greatness and learn how to do the three-card trick using whole banks. If Moist was any judge, any judge at all, the man in front of him was the biggest fraud he’d ever met. And he advertised it. That was . . . style. The pirate curls, the eyepatch, even the damn parrot. Twelve and a half percent, for heaven’s sake, didn’t anybody spot that? He told them what he was and they laughed and loved him for it. It was breathtaking. If Moist von Lipwig had been a career killer, it would have been like meeting a man who’d devised a way to destroy civilizations.”

But the swashbuckling Gilt has, unfortunately for him, crossed Moist after the letters and Adora Belle have done their work. Like any good doppelganger protagonist, Moist changes and grows and gets smarter. Like any bad doppelganger antagonist, Gilt sees no reason to change because he knows everything. By the end, Moist knows something, too: “I’m not Reacher Gilt.” The comparison is made clear at the end when Reacher refuses Vetinari’s offer and walks through the door to his death, confident that there’ll be a floor there because he’s Reacher Gilt.

The supporting characters in here deserve equal attention, but just looking at the big three, you can see how beautifully Pratchett shaped this book around his protagonist, and how his protagonist shaped this book.

The post AIBC: Going Postal: Character, Part Two appeared first on Argh Ink.

June 6, 2016

AIBC: Going Postal: Theme and World

Pratchett’s stories are tremendously fun comic romps, but there are serious themes beneath them. Sometimes he descends into theme-mongering, but in Going Postal, he deals with a light but still savage hand with the capitalist mindset that greed is good and only the strong survive. This is irony at it’s finest since protagonist Moist’s entire life is based on greed and duplicity and yet he’s the one who defeats the perfectly named Reacher Gilt and keeps communication in Ankh Morpork, if not free, then definitely flowing with efficiency and speed that is not hobbled by inefficiency and greed. (He goes on to have Moist save the banking system before it crashes in Making Money, predating the 2008 stock market crash by a year.)

You’d think that that kind of cutting satire wouldn’t be funny, but Pratchett has fantasy on his side; one of the strongest aspects of his thematic work is that it takes place on Discworld, which is right up there with Narnia and Middle Earth as a place that doesn’t exist but really should. Or maybe it does: it’s very easy to see the parallels to New York and London in Ankh Morpork, the chaos of international relations in that city-state’s dealing with other countries that bear suspicious likenesses to places like Australia. Pratchett’s world-building grows out of his satire, he creates countries to make his points, but it’s still brilliant world building, even if you wouldn’t want to visit any of the places he’s built.

If you want a slightly more formal book club start, try these questions:

1. Theme is a universal statement about the human condition. It has no moral dimension, so it can be “Crime doesn’t pay” or it can be “Crime does pay.” There’s a good argument to be made that theme should be embodied in the protagonist, not spelled out on the page but made clear by his or her actions in the story. Our protagonist Moist also has no moral dimension. Does that help or hinder his ability to embody theme by his actions?

2. How is the theme of Going Postal strengthened or weakened by its doppelganger protagonist and antagonist?

3. The line between theme enhancing a story and theme-mongering sinking a story is a very narrow one. It helps that Pratchett tends to use a light hand and to cast his themes in very clear contrasts of Good Guys and Bad Guys. Even so, sometimes he oversteps and the theme crowds out the story. Was there any point here where you felt, “Okay, okay, I GET IT,” or were you with him all the way? Why?

NOTE: This Book Club Post will remain open, so if you haven’t read the book yet, decide to later, and then have things you must say, no worries. I’ve added a “Most Recent Comments” widget to the sidebar so people will know when comments go up on old posts.

The post AIBC: Going Postal: Theme and World appeared first on Argh Ink.

AIBC: Going Postal: Structure

Pratchett puts forty pounds of story in a five pound bag and then tightens the string. How does he do that without descending into chaos (if he does; he kinda likes chaos)?

I think a lot of it is that he always remembers whose story he’s telling. This may story may go all over the place, but it goes all over the place following Moist, who is worthy of being followed. While it does have a classic doppelganger protagonist and antagonist, it also follows the classic doppelganger structure: the protagonist learns and the antagonist doesn’t, so as the protagonist arcs, the antagonist falls behind. In this story character is structure.

If you want a slightly more formal book club start, try these questions:

1. Two prologues. If you skip them, the book is much better. What is it with authors and prologues? (I know, but I’m not telling because it’s rude.)

2. If the story structure is about Moist’s rebirth after death and rise to the heights, it’s also about the post office’s death and rebirth. How does linking character to goal shape this story?

3. There’s a romantic subplot in here, the hero gets the girl, but the girl is not a Girl in the “Be careful, Moist” mode. How does the structure of the love story (and the character of Adorabelle, shown below) not just support but also fuel the main plot?

NOTE: This Book Club Post will remain open, so if you haven’t read the book yet, decide to later, and then have things you must say, no worries. I’ve added a “Most Recent Comments” widget to the sidebar so people will know when comments go up on old posts.

The post AIBC: Going Postal: Structure appeared first on Argh Ink.

AIBC: Going Postal: Character

When you’ve got a protagonist named Moist Von Lipwig, character is obviously going to be a vivid part of your skill set.

Pratchett’s over-the-top satire is not for everybody, but I’d argue that his characters are universal even while being so far off center they’ve slipped over into a different reality (the one where the universe is a turtle with the world on its back).

His villains (and they are villains, not just antagonists) are badder than badder, but they never do anything just for the sake of Evil. His protagonists are doing their best, but their best is often hobbled by their vivid personality flaws: Moist is obviously a textbook example of the flawed protagonist, but Adorabelle is not without her problems, nor is anybody in the supporting cast anything but dented and damaged, albeit that most of them are fairly cheerful about it. The closest thing to a flawless character in Discworld is Vetinari, and even there “flawless” is a judgement call. After all, he would have let Moist plummet to his death. Free will and all.

So let’s talk about why we really love Moist (if you do) even though he’s a predatory con man who lies and cheat and steals his way through his story. Let’s talk about the Hero’s Love Interest, a heroine who chainsmokes, takes no crap from anybody, and tortures the hero throughout the story, for a very good reason as it turns out. And let’s talk about that antagonist, the wonderfully vile and fabulously named Reacher Gilt. And then there’s Stanley and his pins. So much wonderfulness crammed into one hectic story.

If you want a slightly more formal book club start, try these questions:

1. Pratchett is writing so far over the top of reality, he’s at space station level. How then does he make characters named Moist Von Lipwig and Adorabelle Dearheart so rounded and real and human?

2. An antagonist should always be stronger, smarter, faster, and better armed than the protagonist. Bring on Reacher Gilt. How is he a great antagonist for Moist Lipwig? Think doppelganger here: In many ways Gilt and Moist are the same person. How does that strengthen the conflict and therefore the story?

3. Pratchett uses supporting characters to build his world: they form guilds, make plans, flirt and betray and divide and connect in chaotic color behind the Big Story played out at the front of the page. One big example in Going Postal is the fallout from Moist deciding to deliver the mail. Let’s talk about character and world building.

And anything else you want to say.

NOTE: This Book Club Post will remain open, so if you haven’t read the book yet, decide to later, and then have things you must say, no worries. I’ve added a “Most Recent Comments” widget to the sidebar so people will know when comments go up on old posts.

The post AIBC: Going Postal: Character appeared first on Argh Ink.

June 5, 2016

Hey. We’re Going Postal Tomorrow

Just a reminder . . .

This is going to be an EXTREMELY relaxed bookclub. I’ll put up three posts so we can keep the topics sorted–Character, Structure, and Theme–and I’ll put up some things I’ve thought about but then you all can take it from there and we’ll just talk. Because you all do that so well.

See you tomorrow.

The post Hey. We’re Going Postal Tomorrow appeared first on Argh Ink.

June 4, 2016

Cherry Saturday 6-4-2016

Today is Hug Your Cat Day.

It’s also Adopt a Cat Month . . .

Okay, FINE . . .

The post Cherry Saturday 6-4-2016 appeared first on Argh Ink.

June 1, 2016

Person of Interest: “Sotto Voce,” “The Day the World Went Away,” and the Impact of Character

Yeah, I wanted a drink after that last episode, too.

Yeah, I wanted a drink after that last episode, too.

This is Person of Interest at its finest, they’re doing an amazing job of ending this great long-form story, and unlike the idiot shoot-’em-up big finishes so many action movies go out with, PoI is doing brilliant shoot-’em-up big finishes based on character, a mix of pain and joy that becomes exhilaration with mourning. This isn’t a “they didn’t have to die” ending. Like Carter, they really did have to die, and I’m just as upset about their deaths as I am about Carter’s (still), even while I recognize that the deaths were real, necessary to the story, and consequential. The Gang is at that point I love in chaos theory: moving from being into becoming. What they were, they will never be again, not just because of their losses but because of Harold Finch who just reached his breaking point.

Finch created this story, his story, when he created the Machine, and now he’s going to end it and take Samaritan with him. It’s a fine rousing last stand; the tragedy is that he’s forced to do it on the bodies of two people he loved. Since we loved them, too, the tragedy goes deep. But so does the exhilaration: Finch is going to set the Machine free and go out blazing.

I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Sotto Voce

But first, “Sotto Voce” brings back an old adversary and Shaw, but what it really brings home is that the ending of a good story is about character. You can blow up all the buildings you want, do grimdark scenes of gun flare and hurtling bodies, and none of it will matter unless character is on the line.

Fortunately, “Sotto Voce” has character to burn.

I’m not sure when in this episode that I recognized the Big Bad, but it wasn’t much after the halfway point when I thought, “Wait. Didn’t I see this on Burn Notice?” And Elias’s first episode. And . . . Okay, so the big reveal was no reveal at all. If all this episode had going for it was finding out who the Voice was, it would have been a miserable failure.

But there was the innocent cabbie Fusco kept after until he transformed in a moment into the ice-cold hitman, acknowledging Fusco’s skill and tenacity.

There was Elias, genially accompanying Finch to keep him from being killed, threatening the bomb maker with a gun nobody doubted he’d fire, taking care of the Bad Guy in a way that audiences have been waiting for (answering the old “Why don’t they just shoot the bastard?” with “Because it’s better to blow him up”). Not to mention Elias’ soft-voiced promise to pay his debt to Finch, which he’s going to do in a big way in the next episode.

There was Shaw and Root in the park, Shaw prepared to kill herself to save the Gang, and Root prepared to kill herself to save Shaw. The simulation’s Hot Lesbian Sex Scene never felt quite right (because it wasn’t supposed to), but you can’t watch that scene in the park and not recognize that these two women love each other madly.

There was Reese FINALLY taking Fusco up to the roof away from cameras and telling him about the Machines.

And then there was the part that gave me chills, Finch standing in the same place he was standing in the pilot, back then waiting for Reese to be brought to him, now waiting for Reese and a fully informed Fusco to join him, then Root, and then a pale and hesitant Shaw, the five of them standing soberly in the sun together.

I’ve said before that the last act is when everything is stripped away, but I should have said everything but character. When the protagonist has lost everything she was fighting for, when the time to face that final battle is nigh, all the storyteller has left is character. Nobody cares what size gun the Bad Guy is going to pull, nobody cares who throws what punch, the action is important but only important because of what it shows about character. Who is your protagonist when she has nothing left but herself?

And in the case of PoI, what is the Gang when it’s broken down to just its five members, all of them lethal and all of them damaged? That’s what that last scene in the park in “Sotto Voce” is to me, the grimness of five characters who know they’re the last stand before the apocalypse. But that last scene also tells me that if the apocalypse is coming, I want those five on my side.

And then they were four . . .

The Day the World Went Away

This was spoiled for me so I knew what was coming (ARGH). Even so, it may be the best episode of this show in its entire run. The stakes are so high–Finch’s cover is blown and Samaritan is everywhere, ruthlessly hunting them to kill everyone BUT Finch because Samaritan thinks it can brainwash him onto its side. Bring a lot of soap, Samaritan, that’s a really big brain you’re trying to warp.

So Finch begins by escaping the safe house with Elias who is now a close friend, watches Elias die defending him; is captured by Greer who tells him that Samaritan doesn’t want to kill him, it wants to enlist him; is retaken by Shaw and Root and escapes with Root who defeats the following Samaritan agents with a really big gun and a scrunchie before she’s shot; is captured by the police who take his finger prints and reveal his criminal past including his warrant from the FBI for treason; defies Samaritan through the interrogation room camera; and answers the phone when the Machine calls him and hears Root’s voice. The joy on his face when he thinks Root is okay is heartbreaking because in the next moment, the Machine identifies herself: “I chose a voice.” And he knows Root is gone.

But so is Finch. Not just because the Machine gets him out of the police station but because the deaths of Elias and Root have broken his resolve to play by his rules, to be the good guy. In a magnificent soliloquy, Michael Emerson shows Finch transforming as he speaks his determination to bring down the computer program that has no boundaries, and it’s clear that means that his Machine is going to be set free. It’s a magnificent scene for a magnificent character, and it sets up the last three episodes–the climax of this season and the climax for the entire series–as a go-for-broke nothing-left-to-lose blow-out, good against evil once again.

It’s just brilliant.

Weakest Parts

Really brilliant storytelling all the way through.

Smart Story Moves

• “Sotto Voce”‘s Three parallel story lines, three relationships–Finch/Elias, Reese/Fusco, and Root/Shaw–played out in action followed by direct and crucial dialogue, people in a crucible telling each other what they need to know.

• Paying off audience anticipation in scenes we’ve been wanting for a long time: Finch and Elias as no-longer-dueling masterminds working together as quiet-spoken badasses, Reese finally telling Fusco the truth, and the brilliantly done Root/Shaw reunion. It’s a cliche to say that I’d watch a show that was nothing but these people chatting at a picnic, but it’s true: I care about the relationships in this show so much more than I do about the threat of world-domination by an AI, and the only reason I care about that is because the AI is trying to kill Our Gang.

• Setting up the deaths by having Elias talk about where he thought he’d end up (the same place Finch thinks he’ll end up: prison), and by having Root talk about how there are deaths because we’re all just shapes, and the Machine knows the shapes of all of them. When she says that Carter is still alive in the Machine, my heart broke just a little.

* Giving Elias and Root such good deaths, Elias going out on his feet, protecting Finch to the end and Root with that incredible last car chase, steering with her boot while blowing up the Samaritan armored car with a Great Big Gun. If you’re going to kill off characters we love this much, make their deaths magnificent.

• The Machine taking Root’s voice. That’s going to have major emotional reverberations but I all I could think of was, “She’s still alive in the Machine,” just the way she said she’d be.

Favorite Moments

• Bad Guy:”Careful, compassion and loyalty make people weak, easy to exploit.”

Elias: “Well that’s some stinkin thinkin, and why you’re going to lose.”

• The moment in “Sotto Voce” in the park at the end. It’s been awhile since I’ve actually gotten chills watching a story, but seeing Finch back in the park and then Reese and Fusco walking toward him . . . that was a moment.

• The guy from the neighborhood telling Reese how much Elias was loved. I didn’t know I needed to hear that until he said it.

• Root and the scrunchie: Details matter.

You know there’s a lot more in there that I loved, but I’m still overwhelmed, so I’ll come back later and rave in the comments. But really, this is magnificent storytelling, magnificent characterization. PoI‘s world is more violent than it’s ever been, but that violence is in service to story not the other way around, and every gun shot is important because of the characters involved. It seems odd to say about a story so fun of guns and squealing tires, but this episode is about character, as is the entire series. Character is the reason the gunshots matter.

Here’s part of Finch’s monologue in the holding room:

I was talking about my rules. I have lived by those rules for so long, believed in those rules for so long, believed if you played by the right rules eventually you would win. But then I was wrong wasn’t I? And now all the people I care about are dead or will be dead soon enough. And we will be gone without a trace.

So now I have to decide. Decide whether to let my friends die, to let hope die, to let the world be ground under your heel all because I play by my rules. But I’m trying to decide. I’m going to kill you. But I need to decide how far I’m willing to go. How many of my own rules I am willing to break … to get it done.

New PoI Post

Only three more episodes to go, and only one weekly from now on, which is probably a good thing because the impact of these is immense, so stretching them out will help immensely. On the other hand, I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Also, I hate CBS. Cancelling both PoI and Limitless? The entire network is dead to me now.

June 9: “Synecdoche”

June 16: “exe”

June 23: “Return 0”

The post Person of Interest: “Sotto Voce,” “The Day the World Went Away,” and the Impact of Character appeared first on Argh Ink.

May 31, 2016

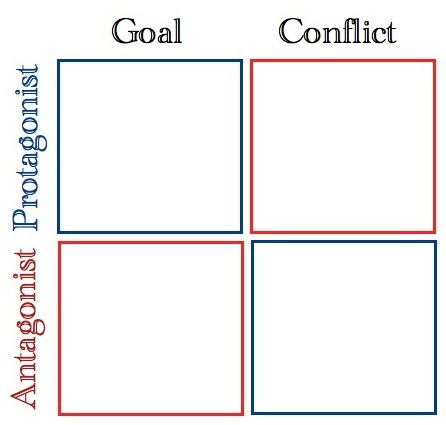

Book Done Yet? The Conflict Box Is A Magical Thing

So after staring into space (along with the fifty other things that had to be done this week) and then losing my computer (I had to run after the dogs and I forgot where I dropped it, so I kept searching the living room which wasn’t a help since it was in the guest room), and getting stung on the bottom of my foot by a wasp (don’t ask), I ended up with an ice pack back in bed, thinking about the antagonist.

At that point, I came to two realizations:

1. Nita and Nick have different antagonists (Nita owns the main plot and Nick gets the subplot).

2. I needed a Conflict Box to figure them out.

The lovely thing about the conflict box is that it’s simple. If my conflict doesn’t fit in that box, I haven’t thought it through, so to make a box, I have to think of my conflict in the starkest terms: What do they want, and how are they crossing each other?

So here’s what I’ve got (details redacted for spoilers):

Nita’s turned out to be pretty simple: Somebody’s killing demons and she’s going to stop them, and that makes the demon killer include her as a target to stop her from interfering. Nita can’t stop going after the killer, it’s her job and her job is her life, and the killer can’t stop killing and trying to kill Nita. Nice simple conflict lock.

Nick’s is trickier. It obviously has to be somebody who wants to be the next Devil, or somebody who wants Nick impeached or deposed so he or she could be the next Devil now. The problem was, the struggle’s taking place on the island which seemed odd. Why not fight him in Hell?

But then I realized that was a smart move. Take him out of the place where he’s the most powerful and then subvert and destroy him while he’s out of his element. So then B’s only problem is how to get him to the island, and that’s where the hellgate comes in: B reports an illegal hellgate and then takes out the first two demons that Nick sends to deal with it, knowing that as a responsible administrator, he’ll come himself the third time.

That gives me two different struggles which is not good because I want a unified book. But if Nick’s antagonist B joins forces with A, that solves that. Then the problem is, Why? Why would an insurgent candidate for Devil join forces with a demon assassin? (I know: They fight crime!) They’d have to have a mutual agreement. I can see why antagonist A would do it: if B would promise to remove the demons from the island once in power, that would be a good partnership. But what good is A to B? That is, how does a demon assassin help a Devil usurper? Gotta be the assassination, right?

That’s a little weak, so I’m cogitating.

But really, conflict boxes. HUGE HELP. (Want one? It’s yours. Drag and drop the image below.)

The post Book Done Yet? The Conflict Box Is A Magical Thing appeared first on Argh Ink.

May 28, 2016

Cherry Saturday 5-28-2016

May is National Salad Month

I waited until now to tell you so you only had to eat salad for three more days.

The post Cherry Saturday 5-28-2016 appeared first on Argh Ink.