Susan M. Weinschenk's Blog, page 8

May 14, 2024

100 More Things #132: READING ONLINE MAY NOT BE READING

One of the ideas I talk about a lot when I give keynotes is that technology changes quickly but humans don’t. Most of the ways that people’s eyes, ears, bodies, and brains work has come about from eons of evolution. And these aren’t likely to change quickly.

I did say most. Reading is an exception. And that’s because reading is not hardwired. Every brain has to learn how to read.

Maryanne Wolf wrote a book called Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain. In it she explains that people’s brains weren’t made to read. Unlike the capacity to walk or talk, reading is not built in. It’s something people learn to do, and, interestingly, there isn’t just one way that the brain reads.

Neuroplasticity And Reading

People’s brains change throughout their lives. The term that’s used is neuroplasticity. The brain reorganizes itself. It forms new neural connections, and sometimes changes where in the brain certain functions occur. This is in response to the environment and what people do each day. Learning to read causes the brain to change, too.

In some ways, people’s brains change in predictable ways when they learn to read, regardless of the language. Kimihiro Nakamura (2012) mapped brain activity with fMRI scans for people who learned to read in French versus Chinese. He found that there are two circuits, one for shape recognition by the eye and another for gesture recognition system by the hand, which are activated and show the same pattern of activity with both languages.

There are some differences in the pattern of activity, though, based on language. For example, there’s more activity in the gestural areas of the brain for people who read Chinese, compared to French. No matter what the language people read in, however, their brains change when they learn to read.

As Wolf points out, parts of the brain that are hardwired for other tasks—for example, shape recognition, speech, and gesturing— create new circuits and neuron connections when people learn to read.

Skimming And Scanning Vs. Reading

The type of reading people do when they sit down—focused and not distracted—to read a book (whether on an e-reader or on paper, whether a novel or nonfiction) is quite different from the type of reading they do when they’re browsing information online. They use different parts of the brain.

People think differently when they’re doing focused reading. Good readers do what Wolf calls “deep reading.” They think while they read. They connect what they’re reading to their own experiences. They come up with new ideas. They go beyond what the author is writing to interpret and analyze. They’re having an internal experience.

Skimming and scanning are a different experience—not worse, just different. People use more visual attention when they skim and scan. They internalize much less. It’s an external experience. These differences between deep reading and skimming and scanning show up on brain image scans.

Designing For Skimming And Scanning Is Best Practice, Right?

If you’re designing products that involve people reading text, you’re probably aware that many people don’t read everything they see on a screen. And you’re probably aware that you need to break text up into smaller chunks, and use headings. These guidelines have been accepted as best practice for online text for several years. However, I’m going to suggest that you think about this in a more radical way than you might be used to.

It’s Not Reading

Based on this new research on deep reading, skimming, and scanning, I’m recommending that you stop thinking of what people do when they go to a website or read an online article as reading. (The exception is when people are reading a book with an online reading device.)

I’m suggesting that reading be defined as follows:

When people sit or stand in one position with little movement and read text on a digital or paper page, when they are not distracted by anything else on the page or anything in their environment, when the only interaction with the device or paper product is to go to the next page or, now and then, go to a previous page, and when they maintain this activity for at least 5 minutes without doing anything else—that is reading.

Anything else involving the processing of words on a screen or a page is skimming and scanning.

Designing For Skimming And Scanning

Most people who design websites, apps, and products aren’t designing for reading as I’ve described it above. My premise is that you’re designing for an activity that’s not reading. Skimming and scanning looks different in brain scans from reading. Skimming and scanning are external experiences, based on visual attention.

If you’re designing for skimming and scanning, assume that people are not thinking deeply about what’s written, they’re probably reading very little of it, they’re skipping over large parts, and they’re not interpreting and analyzing the information.

Reading Is Changing = Brains Are Changing

One more thought: people skim and scan when that’s appropriate and they deep read when that’s appropriate. How wonderful it is that the human brain is plastic enough to learn both, and can change from one to the other when needed.

This switch from reading to skimming and scanning is no problem for people who grew up learning how to deep read, and then, later, learned how to skim and scan. Is it possible that new generations will grow up without learning deep reading at an early age? Or that they may learn skimming and scanning first, and then deep reading? Or maybe they won’t ever learn deep reading?

Wolf hypothesizes that since this brain reorganizing alters the way people think, these changes could have large and unanticipated consequences for how people interact with information. Will humans get to the point where they don’t analyze information they’re “reading” because they skimming and scanning, not reading? Will people get to the point where they don’t have an internal experience when taking in words?

Takeaways

People are probably skimming and scanning your online text, so make sure you follow skimming and scanning guidelines: break information into small bits and use headings.Don’t assume that people have “read” online text.Don’t assume that people have comprehended or remembered online text.Minimize the amount of text you use online.May 7, 2024

100 More Things #131: PEOPLE READ ONLY 60 PERCENT OF AN ONLINE ARTICLE

That is, if they read it at all.

Clicking Doesn’t Mean Reading

As the CEO of Chartbeat, a company that analyzes real-time web analytics, Tony Haile (2014) has seen a lot of data on what people are doing online.

In the advertising world, clicks were king for a long time. A lot of money has changed hands over pay-per-click and page views, both of which measure the success of online advertising by counting clicks. Haile says that’s the wrong measurement.

Haile looked at 2 billion online interactions, most of them from online articles and news sites, and found that 55 percent of the time people spend less than 15 seconds on a page. This means they’re not reading the news articles.

Chartbeat’s data scientist, Josh Schwartz, analyzed scroll depth on article pages. Most people who come to an article scroll through 60 percent of it. Ten percent never scroll, which means they’re not reading much.

Haile says instead of clicks, we should concentrate on the amount of attention the audience gives, and whether they come back.

Some organizations have started using a metric of “attention minutes.”

Sharing Doesn’t Equal Reading

Another action that’s sought after is sharing on social media. The assumption is that if people share an article they’ve read what they’re sharing, right?

The relationship between reading and sharing is weak. Articles that are read all the way through aren’t necessarily shared. Articles that are shared have likely not been read past 60 percent. According to Adrianne Jeffries (2014), most sharing occurs either at 25 percent through the article or at the end of the article, but not much in between.

Takeaways

Don’t assume people are reading the whole article.Put your most important information before the 60 percent point of the article.When you want people to share the article, remind them to do that about 25 percent of the way through the article and again at the end.Don’t assume that if people shared the article that means they read all or even most of it.April 30, 2024

100 More Things #130: HOMOPHONES CAN PRIME BEHAVIOR

You are, unfortunately, working late at night again. You have a report due in the morning but it isn’t quite done, so you’re sitting in your home office trying to finish it.

You decide to take a short break from the report and read one of the blogs you try and keep up with. You read a post from a well-known journalist who is about to leave on a trip overseas. He writes a kind of farewell post and at the end he signs it “Bye!” On the blog page, you see an ad for the journalist’s latest book with a “Buy now” button. You click and buy his book.

Next, you’re skimming a news site and you see a headline: “Is the Fed Chairman Right?” Suddenly you realize it’s getting late and you haven’t finished writing your report. You get back to work.

Was any of your behavior during that interlude “primed”?

Priming is when exposure to one stimulus influences your response to another stimulus. In the example above, you were primed with the word “Bye” (first stimulus) at the end of the blog post you read. Your exposure to “Bye” then affected your response to the second stimulus—“Buy” that was on the “Buy now” button.

That’s not all. Your exposure to the word “Right” (another stimulus) in the news headline primed you to think of the word “write” (the last stimulus), and made you realize you were supposed to be writing your report.

Priming With Homophones

Psychologists and marketing researchers have known about the effects of priming for decades. But realizing that priming works with homophones is a newer discovery.

A homophone is a word that has the same pronunciation as another word, but a different meaning, and sometimes a different spelling.

Here are some examples:

Bye/buy

Write/right

Carrot/carat

Air/heir

Brake/break

Cell/sell

Cereal/serial

Coarse/course

Fair/fare

Know/no

One/won

Profit/prophet

Derick Davis and Paul Herr (2014) wanted to see if homophones would act as primes, and if so, how strongly and under what conditions. Their idea was that homophones would activate the meaning and association of the related homophone, and that this activation would affect behavior. If people saw the word “bye,” they’d be more inclined to buy something.

People Subvocalize When Reading

When people read, they subvocalize—that is, they speak words internally. These words activate memories associated with the words. When people read the word “bye,” they associate meanings such as leaving or going on a trip. But because people subvocalize and say the word to themselves, Davis and Herr hypothesized that the association for the homophone “buy” would also be activated, and that the associations would stay in memory for a short time.

Note:

Since homophone priming is based on subvocalizing, this entire effect is different for every language.)

Suppressing Homophone Activation

Research on reading has shown that a lot of the time people automatically and unconsciously suppress the activation of homophone associations. The better a reader a person is, the more she suppresses the associations.

It’s a myth that good readers don’t subvocalize

If you’ve ever taken a speed-reading course, you may have been told that subvocalizing will slow down your reading. Don’t confuse moving your lips with subvocalizing. It may slow you down to move your lips while you read, but everyone subvocalizes (no sound, no movement). In the case of the homophone effect, it’s not that better readers aren’t subvocalizing. It’s that better readers don’t have as many automatic homophone associations.

So if you’re a pretty good reader, you might be less susceptible to homophone priming—unless you’re under a high cognitive load.

The Cognitive Load Gotcha

It takes some cognitive work to suppress homophone activation. This means that as you become more mentally busy—as your cognitive load increases—your susceptibility to the homophone priming increases, too.

Let’s go back to the example of working on the report late at night and encountering the homophones. Since you’re working late and you have a deadline the next day, it’s possible that you have a fairly high cognitive load, which would make you susceptible to the bye/buy homophone activation.

Embedded Homophones Have The Same Priming Effect

In their research, Davis and Herr tested embedded homophones too, such as “goodbye” and “bye” or “good buy.” They found the embedded homophones followed the same priming activation as single homophones.

Homophone Activation Is Unconscious

Davis and Herr tested 860 participants in their homophone research. None of the participants were aware of the homophone activation that had occurred.

Order sometimes matters for homophone activation

Homophones activate each other most when both words are common words (buy/ bye). But if one of the words isn’t that common (you/ewe), then the order matters for activation. If you see “you” first, you’re unlikely to have “ewe” activated (unless you’re a sheep farmer). However, if you see the word “ewe,” it’s likely that “you” would be activated.

An Ethical Dilemma?

So here’s one of those times when designers have an ethical dilemma. Do you purposely try to get people to do something by messing with homophones? Do you put the word “bye” in your blog post or on your website not too far from the word “buy” in a different context? Do you not only sprinkle the priming homophone, but also up the cognitive load on the page so the person will be even more susceptible? Should I have even included this information in this book if it means that some people will now use it to get people to take an action that’s not in their best interest?

I’m often asked about ethics in my work, because so much of the research I talk about has to do with how to get people to take action. It’s something I think about a lot, although I don’t have a quick answer. The basic question is: “If we use this information from behavioral science research to get people to do what we want them to do, are we being too manipulative? Are we being ethical?”

One point of view is that if you’re trying to get people to do something, no matter what it is, then that is unethical. Another is that if you’re trying to get people to do something that’s good for them (eat healthier, quit smoking), then it’s OK. I fall somewhere between these two ideas.

My take on the research I talk and write about is that these effects are powerful. However, there’s a limit. Using these behavioral science influences won’t give you total control over the other person. I also believe that each designer has to decide for himself or herself where the line is between influence and ethics. Every time you design something, you have to decide where that line is.

Here’s some idea on where my line is usually drawn:

I don’t completely agree with the people who say that it’s OK to use these techniques to change behavior related to eating, smoking, or conserving energy—things that help the individual or help society—but it’s not OK to get people to buy a new refrigerator. Trying to change behavior is trying to change behavior.

I’ve been an expert witness/consultant for the US government on cases involving internet fraud, and this has given me some insight into where the line is on ethical and unethical behavior. Putting your product or service in its best light, and matching your product or service with the needs and wants of your customers—these are OK. Does everyone really need a new refrigerator? Probably not. But encouraging them to buy a new refrigerator now, and to buy it from you, is perfectly fine. Otherwise, we might as well proclaim that all marketing and advertising is unethical, which is probably an opinion some of you have!

Purposely deceiving people, giving them confusing instructions so they don’t know what they’ve agreed to, encouraging them to engage in behavior that harms them or others, or trying to get them to break the law—these are not OK.

Interestingly, homophone priming falls right in the middle of those two places on the continuum. This means that in the work that I do I wouldn’t use homophone priming to get people to take the action I want them to take.

As I said, you’ll have to decide for yourself.

Takeaways

You can use homophones to affect people’s behavior.When you want to increase the power of the homophone effect, increase people’s cognitive load.People are not aware of the homophone priming effect. Think carefully about the ethics of this technique. Don’t use it if you find it to be unethical.April 23, 2024

100 More Things #129 NOUNS SPUR ACTION MORE THAN VERBS

If you’ve ever had to name a button on a website, app, or landing page, then you’ve probably had the moment where you’re going back and forth between options. “Sign up” or “Register”? “Order” or “Shopping cart”?

Is there a way to word these requests, actions, or buttons that encourages people to take action?

Gregory Walton at Stanford studies connectedness and affiliation between people. In a series of experiments, he tested how different labels affect behavior.

Psychologists, and people in general, tend to think that preferences and attitudes are stable. People like opera or they don’t. People like to go dancing or they don’t.

Walton thought these attitudes and preferences might not be so stable after all.

Maybe how people think of themselves—and how that influences their behavior—is more temporary and fluid. And maybe whether they act, or not, can be influenced by labels.

He conducted a series of experiments to test this out. In the first experiment, participants evaluated the preferences of others described with noun labels or with verbs:

“Jennifer is a classical music listener.”

or

“Jennifer listens to classical music a lot.”

He tested a wide variety:

Author

X is a Shakespeare reader.

X reads Shakespeare a lot.

Beverage

X is a coffee drinker.

X drinks coffee a lot.

Dessert

X is a chocolate eater.

X eats chocolate a lot.

Mac/PC

X is a PC person.

X uses PCs a lot.

Movie

X is an Austin Powers buff.

X watches Austin Powers a lot.

Music

X is a classical music listener.

X listens to classical music a lot.

Outdoors

X is an indoor person.

X spends a lot of time indoors.

Pet

X is a dog person.

X enjoys dogs a lot.

Pizza

X is a Pepe’s pizza eater.

X eats Pepe’s pizza a lot.

Sleeping time

X is a night person.

X stays up late.

Sports

X is a baseball fan.

X watches baseball a lot.

Walton tried to use statements that are used in conversation, for example, “Beth is a baseball fan,” and “Beth watches a lot of baseball.” He didn’t use “Beth is a baseball watcher,” even though that’s technically a better word match.

He found that when people read nouns to describe other people’s attitudes they judged those attitudes to be stronger and more stable than when the attitudes were described with the verbs.

In a second experiment, he used similar sentences and had people describe themselves. People would fill in the blanks, for example:

Dessert

I’m a lover. (chocolate . . .)

I eat a lot. (chocolate . . .)

Mac/PC

I’m a person. (Mac/PC)

I use a a lot. (Mac/PC)

Outdoors

I’m an person. (outdoors/indoors)

I spend a lot of time . (outdoors/indoors)

After the participants had filled in the blanks, Walton asked them to rate their strengths and preferences. For example, on a scale from 1 to 7:

“How strong is your preference for this topic?”

“How likely is it that your preference for this topic will remain the same in the next five years?”

“How likely is it that your preference for this topic would remain the same if you were surrounded by friends who did not enjoy what you prefer?”

The results were similar to the first experiment. When there were regular nouns, participants evaluated their preferences as being stronger. Unusual or made-up nouns “baseball watcher” did not have the same effect.

To Vote? Or To Be A Voter?

Christopher Bryan and Gregory Walton (2011) conducted additional studies to see if this idea of nouns and verbs would affect voting.

They contacted people who were eligible to vote, but hadn’t registered yet (in California in the United States). The participants completed one of two versions of a brief survey.

One group of participants answered a short set of questions that referred to voting with a noun:

“How important is it to you to be a voter in the upcoming election?”Another group answered similar questions worded with a verb:

“How important is it to you to vote in the upcoming election?”The researchers’ hypothesis was that using the noun would create more interest among the participants, and that they’d be more likely to register to vote.

After completing the survey, the participants were told that to vote they would need to register and they were asked to indicate how interested they were in registering.

Participants in the noun group expressed significantly more interest (62.5 percent) in registering to vote than participants in the verb group (38.9 percent).

Bryan and Walton didn’t stop there. They recruited California residents who were registered to vote but hadn’t yet voted by mail. They used the same noun and verb groups the day before or the morning of the election.

They then used official state records to determine whether or not each participant had voted in the election. As they had predicted, participants in the noun condition voted at a significantly higher rate than participants in the verb condition (11 percent higher).

They ran the test again in New Jersey for a different election and, again, the people in the noun group voted more than those in the verb group.

Invoking A Group Identity

I have a theory about this, too. In How to Get People to Do Stuff, I wrote that everyone has a need to belong. Using a noun invokes group identity. You’re a voter, or you’re a member, or you’re a donor. When you ask people to do something and phrase it as a noun rather than a verb, you’re invoking that sense of belonging to a group and people are much more likely to comply with your request.

Takeaways

When naming a button on a form or landing page, use a noun, not a verb: “Be a member” or “Be a donor” instead of “Donate now.”When writing a description of a product or service, use nouns instead of verbs. For example, say, “When you’re ready to be an expert, check out our training courses,” rather than “Check out our training courses.”Use common nouns. Don’t make up words just to have a noun.April 16, 2024

100 More Things #128: IF TEXT IS HARD TO READ, THE MATERIAL IS EASIER TO LEARN

For years, I—and most other designers I know—have believed, and written, and taught that if you want whatever you’re designing to be easy to understand and use, then you have to make it easy to read. You have to use a font size that’s large enough, a font type that’s plain and not too decorative, and a background/foreground combination that makes it legible.

So imagine my surprise at discovering research—not just one study, but several—that shows that if text is harder to read, it’s easier to learn and remember. Apparently being easy to read isn’t the same thing as being easy to learn.

The underlying assumption that’s been leading us astray is that reducing the cognitive load (the amount of thinking and mental processing) that people have to do is always a good thing. It is often a good thing, but instructional design theory has claimed for a long time that increasing the amount of work that people do to learn information often leads to deeper processing and better learning. Is it possible that hard-to-read fonts stimulate deeper processing?

The Interesting Twist Of Disfluency

A term that learning psychologists use is “disfluency.” Connor Diemand-Yauman (2010) defines this as:

The subjective, metacognitive experience of difficulty associated with cognitive tasks

Disfluency is a feeling that something is difficult to learn. Fluency is a feeling that something is easy to learn.

Diemand-Yauman notes that when people feel that something is hard to learn, they process the information more deeply, more abstractly, and more carefully. The disfluency is a cue that they haven’t mastered the material, and so they’d better pay more attention. The result is that they learn it better and remember it longer. Fluency, on the other hand, can make people overconfident, so they don’t pay attention as well and they don’t learn the material as deeply.

The chapter on How People Think and Remember talks about Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow, and about System 1 and System 2 thinking. When information is disfluent, people switch from automatic, intuitive easy thinking (System 1) into effortful and careful thinking (System 2). And this System 2 thinking helps them learn and remember.

Diemand-Yauman researched the idea that a hard-to-read font would lead to better learning and remembering. He gave participants information on three made-up species of space aliens. The participants had to read the material and learn about each species. Each alien species had seven features. (He was attempting to mimic what it’s like to learn categories of animals in biology class, but trying to control for previous knowledge.)

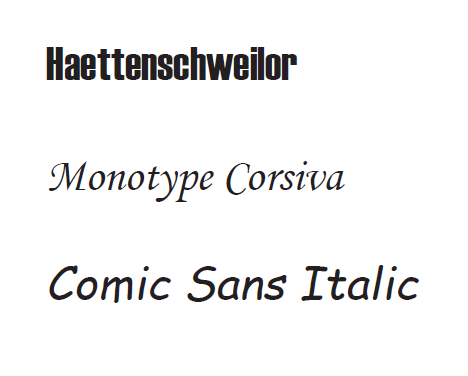

Some of the participants were in the “disfluent condition.” They read information about the alien species in 12-point, gray text. Some participants’ text was in Comic Sans MS, and some was in Bodoni MT:

Note

The examples above use the same fonts as the experiment, but the information itself is not exactly the same as the information used in the experiment.

Diemand-Yauman comments that although the font differences are obvious when the text is presented together in this way, since participants saw only one font, the effect was more subtle.

Participants had 90 seconds to memorize the seven pieces of information of all three alien types. Then they were asked to do other, non-related tasks as a distraction. And after that, they had a memory test for the alien information. For example, they were asked, “What does a temaphut eat?”

He found that people in the disfluent condition remembered significantly more information (14 percent more) than the people in the fluent condition. There was no difference between the two disfluent groups (Comic Sans and Bodoni).

Next Diemand-Yauman wanted to see if the same effect would be true in a more realistic setting. He took the study to a high school (in Ohio in the United States) and tested 220 students. He screened the classes for those where the same teacher had been teaching at least two classes of the same subject and difficulty level and with the same learning material. The experimenters took all the worksheets and PowerPoint slides and changed the font. (The experimenters did not meet the teachers or the students or visit the class.)

Classes were randomly assigned to either a disfluent or a control category. The disfluent classes used material that was switched to one of these fonts:

In the control classes, no changes were made to the fonts. Teachers and students didn’t know the hypothesis that was being studied. They didn’t know whether they were in a fluent or disfluent group. The material was taught the same way it normally was taught. No other changes were made in the classrooms or the instruction.

Students in the disfluent condition scored significantly higher on their regular classroom tests. On a survey asking if they liked their course or course material, there were no differences in these preference ratings. There was no difference among the different disfluent fonts.

So, What’s a Designer To Do About Fonts?

If you design textbooks or e-learning modules, then this research has direct relevance to you. But what about people who design other things, like websites, instructions, or product packaging? What if you’re putting out a series of marketing emails? What should you do about fonts?

You might be tempted to make a distinction between what people are reading for information and what they’re reading in order to learn and remember. But that may not be as simple a distinction as it sounds. If people are reading a blog post about current events, are they “just reading”? Don’t they want to understand, learn, and remember the information?

I can’t make myself recommend that you use a font that’s slightly harder to read than you’re used to if you want people to learn and remember your content. However, that’s what I should say.

Learn better or believe more?

The research on disfluency has to be applied carefully. So far this chapter has talked about learning information and remembering it. If you’re trying to convince people that something is true, then you’re better off making it easy to read. In the chapter on How People Decide and Feel, you learned about “truthiness”—the idea that some things feel more true.

Back in 1999, Rolf Reber and Norbert Schwarz showed that text written in different colors on different backgrounds influenced whether people believed the information. Participants found information in hard-to-read background/foreground colors, like this,

Brazil nuts are a good source of the trace mineral selenium.

to be less believable than information in easier-to-read colors.

Takeaways

When the most important goal is for people to believe that what they’re reading is true, make the text as legible as possible, using a simple font and plenty of contrast between the text and the background.When people already believe the information and the most important goal is for them to learn and remember it, consider using a font that’s slightly harder to read. If the font is slightly harder to read, then people will learn and remember the information better.April 9, 2024

100 More Things #127 PEOPLE NEED FEEDBACK

If you’ve ever deleted some information and then realized that you didn’t want to delete it and tried to undo the action you will realize how important feedback is to humans.

The computer doesn’t need to tell you that it in fact reversed the action and your files are still there. But the human needs to hear it. People need feedback and reassurance in situations like this, but they also like to get feedback. Humans like to get feedback about what is going on, what has just happened, what is likely to happen. Here are some examples of the type of feedback you should build in to your interactions:

Critical Actions

As in the example above, if people have taken, are about to take, or are trying to undo previously taken very important interactions, then give them feedback on where they are in the process, what just happened and what is going to happen next.

Progress Indicators

If people have to wait while something happens, such as files uploading, or software installing, show them a progress indicator. It is not enough to show a wheel going round and round. There should be an indication, such as a solid bar filling in, or the number of files yet to be transferred, so that people can get a sense of how slowly or quickly the process is going.

Steps Completed

If people are going through a process that requires several steps, for example, filling out data on a series of screens, provide information on how many steps there are altogether and where they are in the process, for example, “Step 3 of 7”.

Takeaways

If you want people to feel comfortable with their interactions with your product you need to build in feedback.The higher the “stakes” of the human activity the more important feedback is.Make sure your feedback is clear and concise.Prototype and research how much feedback is best for this particular situation.April 2, 2024

100 More Things #126: PEOPLE ARE EASILY BORED

People don’t like being bored. It’s boring to be bored. People prefer taking action because it provides a sense of control and reduces uncertainty.

One of the reasons that modern apps and social media are so popular is that they are easy to use in situations where you are waiting and would normally be bored, for example in airports waiting for a flight, on a train waiting to arrive at your destination, at the doctor’s office waiting for your appointment.

Maister (1985) and Eastwood (2012) discuss the research that shows that waiting is associated with a loss of control and a lack of information.

If waiting is combined with mild anxiety (is the plane going to be on time?) then it is even more likely that people will start using devices in order to get rid of boredom as well as provide a distraction from anxiety.

Takeaways

People do not like being bored and will interact with almost anything to avoid boredom.If you want people to engage with your app, software, or product make it easy to use in small chunks while they are waiting.March 27, 2024

Human Tech Podcast Episode #164: The State of UX Ohio

Keith Instone and Adam Deardurff join the show to talk about their work doing research for the State of UX in Ohio. We talk about common issues facing many UX communities, but now armed with research.

March 26, 2024

100 More Things #125: CURRENT EMOTIONAL STATES HAVE OUTSIZED INFLUENCE

People are strongly influenced by the emotional state they are in. Later, when thinking back on an event, they may not remember how emotionally charged they were in the moment. This may lead to inconsistent predictions about future behavior.

Research by Morewedge (2005), Ariely and Lowenstein (2006) and Wilson (2003) shows that memory of emotions, and predictions of future emotions is not accurate, and can be easily influenced. If you do not get the emotional rating in the moment when someone is having an emotion, then that person’s future memory of the event can be biased by up to 3x.

When people forecast how they will feel in the future, or how they felt in the past, they often extrapolate based on their current situation: also known as “implicit bias”.

When people are in a “hot” state (hungry/mad/aroused/stressed), they usually predict their future needs or thoughts only in that “hot” state.

When people are in a “cold” state (full/relaxed/chill/bored) they usually predict their future needs or thoughts only in that “cold” state.

The theory is that hot states act as an amplifier of sorts. Whatever feelings you have in a cold state are amplified several times over in a hot state. This intensification of feelings can change priorities and create tunnel vision.

Takeaways

Avoid asking people to predict how they will feel in the future, since they are unlikely to be accurate with that prediction.Instead of using surveys that are emailed at some point after an experience to find out how someone felt about an event in the past, consider using more immediate feedback mechanisms.March 19, 2024

100 More Things #124: BRAIN ACTIVITY PREDICTS DECISIONS BEFORE THEY’RE CONSCIOUSLY MADE

Imagine you’re scanning music on your smartphone to decide what to listen to next. You’re looking at a list of songs. You decide which song you want, and then you move your finger to touch the name of the song to start it playing. What’s so interesting about that?

What’s interesting is that your description of what happened isn’t what actually happened.

Your experience is that:

You make a conscious decision about what song you want to hear.You move your muscles to select the song.But here’s what really happens:

Unconscious parts of your brain make the decision of what song to listen to.Those unconscious parts of your brain communicate the decision to other areas of the brain that control your motor movements.Your arm/hand/finger start to move to execute the decision.Information on what the decision was (finally) appears in your conscious brain areas.You have the conscious experience of picking a song.You use your finger to press the name of the song.Brain scan research by Chun Siong Soon (2008) shows that it takes about 7 seconds from the time you make an unconscious decision to when your conscious brain thinks you have made the decision.

Not Just For Motor Movement

But what about decisions that don’t involve motor movement? Maybe that 7-second lag is just for moving muscles.

Soon (2013) devised a different experiment to see if the same delay holds for making abstract decisions that don’t involve simple motor movements. He found similar results. Up to 4 seconds before the person was aware of making a conscious decision, unconscious areas of the brain had made the decision and started acting on it. In this experiment, participants had to decide whether to work on a word task or an arithmetic task. Two areas of the brain would become active signaling that the decision had been made, but the participant would not yet be aware of the decision. In fact, parts of the brain having to do with working with words versus doing arithmetic tasks were alerted as soon as the decision was made, and still the participant wasn’t aware that he or she had even decided.

The brain activity was so clear that researchers could not only see that a decision had been made, but also tell the participant what the decision was. The researchers knew what each person had decided before the person knew. Not only that, the researchers knew exactly when the decision would be made, as well as when the participant would consciously know that the decision was made.

People who write about this research like to discuss the implications of this research: Is there really such a thing as free will? Is it possible to stop action on a decision after it’s made, but before it’s acted on and before the person even realizes he’s decided? Is it possible to manipulate peoples’ brains so they think the decisions they are making are their own, but in reality those decisions would be stimulated from the outside?

Although these are all interesting questions, they may not seem to be very practical from a design perspective.

But there is a practical impact of this research for designers: How much do we rely on what people say they did or say they are going to do? It’s common for designers to interview their target audience for a product or service to find out things such as:

How do you do this task currently?How do you go about making decisions about x?Do you prefer A or B?What would you do next?Which of these would you choose?Designers ask target audiences these questions before designing, while designing, and after designing. Many have been taught that asking these questions of a target audience and acting on their answers is best practice for design and market research.

But Soon’s research tells us that most—probably all—decisions and most mental processing of any kind happens unconsciously. So asking these questions and listening to answers that have been filtered through conscious thought may not be the best strategy. People don’t actually know why they do what they do, or when they actually decided.

Your target audience will answer these questions as though they really know the answer, because they’re unaware of all this unconscious processing going on. They can be very convincing with their answers of exactly what they thought and how they decided, and the exact moment they decided, because they really believe what they’re saying, even though that’s not actually how it happened.

Since few designers have access to expensive fMRI machines or the training to use them, we’ll probably keep asking the questions. But it’s important that we admit that answers don’t actually tell us what is or will be going on in the brains of the target audience.

As tools for measuring brain activity become more sophisticated, they’ll also become more affordable and easier to use. Eventually designers will all hook up test participants to machines to measure brain activity, heart rate, galvanic skin response, and so on. Some already are. There are some reliable biometrics tools available as I write this book, although some are still very expensive, and many are hard to learn to use.

Takeaways

Refrain from making design decisions based entirely on what people say they would do. You can take this information into account, but don’t use it as the basis for major design or redesign decisions.Watch how people actually interact with your products and services, then use this insight into their behavior to inform how to change them to better suit people’s needs.Biometric equipment for body/brain measurements will only improve and become more affordable. Begin planning how and when you’ll incorporate this feedback into your designs so you don’t have to rely on the (faulty) conscious verbalizations of your target audience.