Sherilyn Decter's Blog, page 2

March 26, 2022

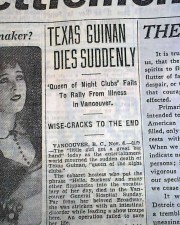

TEXAS GUINAN

TEXAS GUINAN

“Give the little girl a big hand”

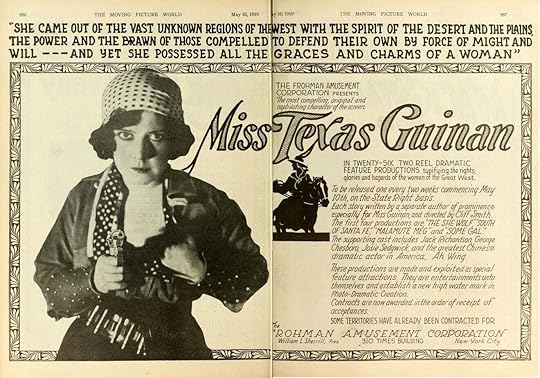

The Wild West Years

The Wild West Years Mary Louise Cecilia “Texas” Guinan, born in Waco, Texas, in 1884, was the first female Western movie star, a gun-slinging, bareback-riding cowgirl in three-dozen silent films in Hollywood (such as Two-Gun Girl and Lady of the Law).

Mary Louise Cecilia “Texas” Guinan, born in Waco, Texas, in 1884, was the first female Western movie star, a gun-slinging, bareback-riding cowgirl in three-dozen silent films in Hollywood (such as Two-Gun Girl and Lady of the Law).

As her reputation and notoriety grew, Texas set her sights on New York. The brainy, brassy girl from Waco landed several starring roles on Broadway, where her acerbic wit defined her.

Her big chance arrived on January 17, 1920, with Prohibition. All over the city, speakeasies, usually small dives, sprouted up. For those seeking entertainment to go with their liquor, a profusion of gaudy nightclubs beckoned. New York’s famous restaurants—Delmonico’s, Sherry’s, Jack’s—gave way to the new clubs, more fun to visit, after all, since patrons could enjoy the additional naughty pleasure of thumbing their noses at the law.

The ‘hello, sucker‘ years

Texas Guinan dyed her brunette hair flashy blond, gussied up her blowsy figure in glittery clothes, cultivated the right underworld connections, and went to work as a nightclub hostess.

Texas Guinan dyed her brunette hair flashy blond, gussied up her blowsy figure in glittery clothes, cultivated the right underworld connections, and went to work as a nightclub hostess.

In 1923, Guinan was hired as a singer by Emil Gervasini and John Levi, owners of Beaux Arts speakeasy. According an article written by Majorie Corcoran in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on December 18, 1927, Guinan was paid $50,000 to sing at the speakeasy. That’s the equivalent of almost $715,00 today — not bad for a 1923 singer/manager/hostess/actress.

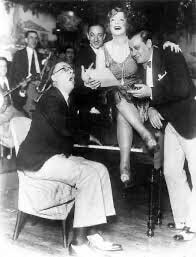

Having seen her perform at the Beaux Arts, New York show producer Nils Granlund introduced Texas to Larry Fay, a notorious rumrunner. She became the hostess and mistress of ceremonies at Fay’s El Fey club, one of the famed illegal speakeasies in New York. The club, on 46th Street near Broadway, opened from midnight to 5 a.m. It stood at the top of stairs leading to a door with a peephole. Inside, the silk-walled club seated about 80, with a small stage for chorus girls.

At the El Fey, Texas originated a live bantering routine for patrons. Standing or seated in the middle of the club, she would greet customers with her line, “”Hello, Sucker! Come on in and leave your wallet on the bar.” She might lead everyone in a song, promise the crowd “a fight a night or your money back,” or crack, “You may be all the world to your mother, but you’re just a cover charge to me.” She referred to rich guys as “butter and egg men.”

Her guests included celebrities of the day: Babe Ruth, Charles Lindbergh, Charles Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino, Clara Bow, Gloria Swanson, England’s Lord Mountbatten and Edward Prince of Wales, plus various gangsters and seedy types. Once during a raid, Texas is said to have had the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII)) don an apron and cook some eggs to pose as an innocent employee and prevent his arrest.

While still working at the King Cole room, she visited Fay’s club at 105 West 45th Street, and found the décor opulent, the entertainment boisterous, and the whiskey, though outrageously overpriced, plentiful. She was soon presiding there from a ringside table, wisecracking with performers and customers.

Giving her a cut of the profits, backing her up with a sexy chorus line, and allowing her free rein, Fay gave Texas the setting she liked. That he was a racketeer with disreputable connections, that secret mob money helped bankroll his club, and that gangsters frequented it—none of this troubled Texas. After too many years of middling show-biz success, on the threshold of middle age, at last she had the celebrity she craved.

Giving her a cut of the profits, backing her up with a sexy chorus line, and allowing her free rein, Fay gave Texas the setting she liked. That he was a racketeer with disreputable connections, that secret mob money helped bankroll his club, and that gangsters frequented it—none of this troubled Texas. After too many years of middling show-biz success, on the threshold of middle age, at last she had the celebrity she craved.

As the twenties began to roar, the El Fay Club attracted anyone with money to burn and a yen for illicit fun. Texas reeled in customers as did no other speakeasy hostess during the Prohibition years. Pleasure-seeking patrons, respectable and not, elbowed one another for the privilege of having Texas and Fay empty their wallets. From well-heeled Wall Streeters and Ivy League collegians savoring big-city high life to famous athletes, prominent (if errant) politicians, and mobsters galore, good- time Charlies from every walk of life converged on El Fay to whoop it up with Texas and her chorus girls.

Rare footage of Texas entertaining the crowds at El Fey.

Nights at the El Fay, and later at Texas’s other clubs, blended alcohol-fueled mirth and sportive bedlam. Armed with a clapper, a police whistle, and her ever-derisive wit, wrapped in ermine, and sporting an array of gigantic hats, Texas impaled big spenders with insults and made them love it. “Hello sucker,” her blunt welcome to fat cats on a spending spree

How famous was Guinan? The eminent Edmund Wilson described her as “a formidable woman, with her pearls, her prodigious gleaming bosom, her abundant yellow coiffure, her bear trap of shining white teeth.”

Journalist Lois Long (herself quite a formidable woman—she was the quintessential flapper/reporter; her nom de plume was “Lipstick”) wrote about Guinan in the October 9, 1920, issue of The New Yorker: “Mind you, there is one woman who gets away with vulgarity. And that, of course, is Texas Guinan . . . . The club is terrible. It is rowdy, it is vulgar, it is maudlin, it is terrifically vital . . . . At any rate, the place, after two o’clock, is always jammed to the doors . . . . Oh, it is a tough and terrible place, but everybody should go once in a lifetime.”

After authorities raided and closed the El Fey, Guinan and Fay opened Texas Guinan’s Club on West 48th Street, and when police closed it, they returned to the old location of the El Fey. She drank coffee, not alcohol. In 1925 she produced and starred in a vaudeville act, “Texas and Her Mob.”

She and Fay later opened the Del-Fey Club in Miami the same year. By her own account, they once took in $700,000 in less than a year

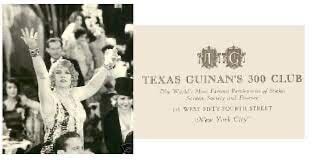

She left Fay (with the aid of mobster Owney Madden, who convinced Fay to let her be) and opened her own place, Texas Guinan’s 300 Club, on West 54th Street. She led a revue on Broadway called Padlocks of 1927 that fell flat with critics. Her company performed an irreverent song, “Oh, Mr. Buckner!” about Emory Buckner, the U.S. attorney of New York and enthusiastic prosecutor of speakeasy owners in the mid-1920s.

She left Fay (with the aid of mobster Owney Madden, who convinced Fay to let her be) and opened her own place, Texas Guinan’s 300 Club, on West 54th Street. She led a revue on Broadway called Padlocks of 1927 that fell flat with critics. Her company performed an irreverent song, “Oh, Mr. Buckner!” about Emory Buckner, the U.S. attorney of New York and enthusiastic prosecutor of speakeasy owners in the mid-1920s.

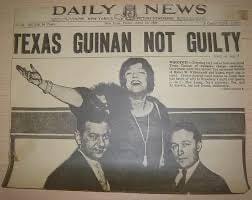

She was arrested in 1927 at the 300 Club on suspicion of a Volstead violation. Freed on $1,000 Bail with Nine Employees After Nine Hours of Mirth in Cell,” screamed typical headlines.

Clad in a garish costume, Texas sounded off as police escorted her to a waiting Black Maria: “Play the `Prisoner’s Song,’ ” she firmly told the orchestra. To which a gruff detective wittily retorted, “Give the little girl a big handcuff.”

At the 47th Street police station, Texas entertained a horde of arrested guests, reporters, photographers, police, and federal agents with several renditions of the song, joined by those 300 Club patrons who hadn’t yet collapsed from exhaustion. As the reporters dutifully noted the antics for breakfast consumption, the cops and feds relaxed, and everyone enjoyed the show, which lasted, off and on, for nine hours. It was sure better than chasing mobsters and dodging bullets.

“I like your cute little jail,” Texas cooed after a night in the West 30th Street slammer, “and I don’t know when my jewels have seemed so safe.”

“I like your cute little jail,” Texas cooed after a night in the West 30th Street slammer, “and I don’t know when my jewels have seemed so safe.”

As for Texas, with the decade gradually slipping away, she continued to start up club after club: Club Intime, Salon Royale, the Argonaut—one after another, the hot spots opened, only to have the police padlock each in turn.

Sometimes, when her club had quieted and closed for the night and day began to break, Texas, accompanied by her manager and a few girls, would have herself driven to a quiet Long Island beach, where she untypically relaxed for a few hours, away from the accustomed pandemonium of her ordinary life.

It was a strange isolation for this driven woman; evidently there was a hidden side of her that needed tranquil hours and fresh air away from the smoke, spotlights, noise, and booze-charged gaiety. Then, the exertions of the night drained away, as her companions dropped from fatigue, she went home to Greenwich Village to her mom and dad and her plethora of gewgaws. And to sleep until the all-night tempests began again.

‘Time to take the show on the road‘ yearsOn October 24, 1929, after several warning spasms, the stock market crashed, wrenching the lives of most Americans. With the ensuing bankruptcies and spiraling unemployment, Texas and her underworld cohorts were in trouble. As former business executives sold apples on street corners, wallets once bulging with money for illegal booze and demimonde high life were now thin and empty.

Texas did her best to keep the good times rolling. As she quipped: “An indiscretion a day keeps the Depression away.”

In 1929, Guinan played a character based on herself, a nightclub owner named “Texas Malone,” in a movie melodrama, an early talkie, Queen of the Night Clubs (the film footage is lost, but some of the audio survived).

In 1929, Guinan played a character based on herself, a nightclub owner named “Texas Malone,” in a movie melodrama, an early talkie, Queen of the Night Clubs (the film footage is lost, but some of the audio survived).

In 1933, months before her death, she was in the movie Broadway Through a Keyhole, in which the director showcased her bantering to customers as she did in her speakeasy days and delivering her “Hello, suckers!” line. She took a performing act, “Too Hot for Paris,” on a national tour to record crowds.

But on November 4, 1933, while backstage after a show in Vancouver, she fell ill with ulcerative colitis and died the next day while undergoing surgery – exactly one month before Prohibition ended. Twelve thousand people attended her funeral in New York.

But on November 4, 1933, while backstage after a show in Vancouver, she fell ill with ulcerative colitis and died the next day while undergoing surgery – exactly one month before Prohibition ended. Twelve thousand people attended her funeral in New York.

To New York and the rest of the country Texas was a flaming leader of a period which was a lot of fun while it lasted.”

The casket was open at Guinan’s request, “so the suckers can get a good look at me without a cover charge.”

“T” for Texas, “G” for Good Times

Other blog posts in the Hooch ‘n Hellraisers series:

Hooch ‘n HellraisersWhiskey WomenQueens of the SpeakeasiesBelle LivingstoneHelen MorganComing soon….

Hoochie-Coochie Hooch HaulersThe post TEXAS GUINAN appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

QUEENS OF THE SPEAKEASIES

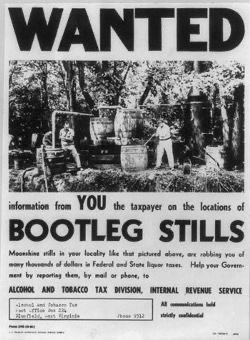

When Prohibition took effect in America on January 17, 1920, many thousands of formerly legal saloons across the country catering only to men closed down. People wanting to drink had to buy liquor from licensed druggists for “medicinal” purposes, clergymen for “religious” reasons, or illegal sellers known as bootleggers.

However, there was another option available… to enter private, unlicensed barrooms, nicknamed “speakeasies” for how low you had to speak the “password” to gain entry so as not to be overheard by law enforcement. These illicit bars were also known as “blind pigs” and “gin joints”. Ranging from fancy clubs with jazz bands and ballroom dance floors to dingy backrooms, basements and rooms inside apartments, they multiplied, especially in urban areas.

Speakeasies became synonymous with the Roaring Twenties. Generally ill-kept secrets, owners exploited low-paid police officers with payoffs to look the other way, enjoy a regular drink, or tip them off about planned raids by federal Prohibition agents.

In the early days of Prohibition, speakeasies sold smuggled imported liquor. However, as Prohibition dragged on, bootleggers who supplied the private bars would add water to good whiskey, gin and other liquors to sell larger quantities. Others resorted to selling still-produced moonshine or industrial alcohol, wood or grain alcohol, even poisonous chemicals such as carbolic acid. The bad stuff, such as “Smoke” made of pure wood alcohol, killed or maimed thousands of drinkers.

To hide the taste of poorly distilled whiskey and “bathtub” gin, speakeasies offered to combine alcohol with ginger ale, Coca-Cola, sugar, mint, lemon, fruit juices and other flavorings, promoting the enduring mixed drink, or “cocktail,” in the process.

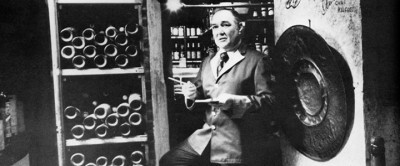

Speakeasies often went to great lengths to hide their stashes of liquor to avoid confiscation – or use as evidence at trial — by police or federal agents during raids. At the 21 Club on 21 West 52nd in New York City, the owners had the architect build a custom camouflaged door, a secret wine cellar behind a false wall, and a bar that with the push of a button would drop liquor bottles down a shoot to crash and drain into the cellar.

Perhaps the most elaborately disguised vault in New York City, ’21’s Wine Cellar was built to be invisible. Behind several smoked hams that hung from the basement ceiling and a shelved wall filled with canned goods, stood a perfectly camouflaged 2 1/2 ton door that appeared to be part of the wall. Opened only by inserting a slender 18″ meat skewer through one of many cracks in the cement wall, the secret door silently slid back to reveal ’21’s most coveted treasure: two thousand cases of wine.

Prohibition didn’t work in the Garden of Eden. Adam ate the apple.Prohibition and its speakeasies offered entrepreneurial women an unprecedented business opportunity managing and owning these new drinking establishments. Whether to supplement the family income, or as the sole support for her family, many women were inspired by the money that could be made by running shoestring speakeasies of their own. These small scale speakeasies were often called “home speaks” or “beer flats” and were run out of living rooms or from basements.

Papa’s in the shed, mixing up the mash;

Junior’s in the parlor, counting all the cash;

Mama’s in the kitchen, washing out the mugs;

Sister’s in the pantry, filling up the jugs.

Annonymous

In 1928, Prohibition officials estimated that Chicago had five thousand beer flats, often run by women. Replacing the corner saloon, they served as gathering places for the locals and tended to thrive in the blue-collar neighborhoods where ethnic groups had a strong tradition of beer drinking. As a general rule, strangers weren’t welcome in these mom-and-pop places, so the patrons knew one another, and the beer flat had an intimate, clubby feel. Typically, the drinkers sat at card tables in the family’s living or dining room, and the beer was served from a barrel in the kitchen.

As a general rule, strangers weren’t welcome in these mom-and-pop places, so the patrons knew one another, and the beer flat had an intimate, clubby feel. Typically, the drinkers sat at card tables in the family’s living or dining room, and the beer was served from a barrel in the kitchen.

In Barre, Vermont, the granite industry employed many men in hazardous workplaces where they inhaled dust that caused chronic disease. These diseases, combined with the Spanish flu epidemic, produced a large number of widows in the Barre after World War I. The women had few job choices. Some tried to make ends meet babysitting, doing laundry, or cleaning houses.

A few enterprising Barre widows scraped together enough money to buy a supply of booze and turn their homes into bars. After work, men would come to enjoy a drink and play a friendly game of cards. “Men in Barre were thankful for the widows,” a local resident said. “It gave them a place to drink, hang out with friends. The widows didn’t get rich, but they made enough money to pay their bills.”

“Successful (Prohibition-era) red-carpet speakeasies and nightclubs were a mix of high society, artistic wits, and seedy mobsters.” However, women were also infamous in the Roaring Twenties for running some of the more upscale and exclusive private clubs that catered to a very different kind of clientele.

However, women were also infamous in the Roaring Twenties for running some of the more upscale and exclusive private clubs that catered to a very different kind of clientele.

During Prohibition, no city had more illegal speakeasies than New York City, an estimated 32,000, most of them unattractive “clip joints” with cheap booze and suggestive women serving as shills to make men spend more.

Three women who ran stylish nightclub-type speakeasies for the affluent crowd – Texas Guinan, Helen Morgan, and Belle Livingstone — dominated New York’s nightlife from the mid-1920s to the early 1930s. You can read more about these feisty trailblazing businesswomen here.

Every Night Was Ladies’ Night During Prohibition Of course, I can’t talk about women owning speakeasies without mentioning their clientele.

Of course, I can’t talk about women owning speakeasies without mentioning their clientele.

While women hadn’t been typically allowed in men-only saloons prior to Prohibition, speakeasies became among the first spaces outside of church where men and women could gather and socialize together.

With thousands of underground clubs, and the prevalence of jazz bands, liquor-infused partying grew and had profound social effects. The term “dating” originated during the “Roaring Twenties” – young singles meeting without parental supervision. Gasp!

Fiction Inspired by TruthAs a writer of historical fiction who is also fascinated by the way entrepreneurial-minded women thrived during Prohibition in America, women running speakeasies seem to pop up in many of my books.

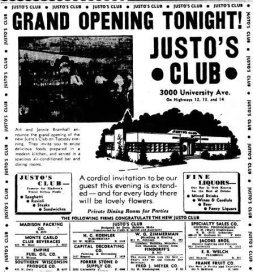

A reporter described Justo as “pretty and vivacious.” And said she catered to “a better class of the student business.” Her clientele included hip young faculty members as well as Joe College and Betty Coed. Her speakeasy was the “rendezvous for many a collegiate whoopee party.”

Jenni Justo out of Madison, Wisconsin was a historical figure who I fictionalized in my serial The Unstoppable Jenni Justo. Both in real life and in the serial, Jenni takes over running the family’s speakeasy, eventually expanding it to take advantage of the local university crowd.

Jenni Justo out of Madison, Wisconsin was a historical figure who I fictionalized in my serial The Unstoppable Jenni Justo. Both in real life and in the serial, Jenni takes over running the family’s speakeasy, eventually expanding it to take advantage of the local university crowd.

After Prohibition was repealed, the real-life Jenni transitioned it into a legitimate establishment that served patrons in Madison for many years.

The popular Rum Runners’ Chronicles series features the story of Edith Duffy, widow of notorious Philadelphia bootlegger Mickey Duffy. (Mickey is another historical person who becomes fictionalized in my novels.)

Arriving in Miami after Mickey’s funeral and at a crossroads in her life, Edith turns to what she knows best and opens a speakeasy. Perched on the edge of the everglades and the ocean, Gator Joe’s is in a little place called Coconut Grove just outside Miami. After a tragic fire, Edith rebuilds it even bigger and better as the nightclub Good Times.

Other blog posts in the Hooch ‘n Hellraisers series:

Hooch ‘n HellraisersWhiskey WomenBelle LivingstoneHelen MorganTexas GuinanComing soon….

Hoochie-Coochie Hooch HaulersThe post QUEENS OF THE SPEAKEASIES appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

HELEN MORGAN

Helen Morgan: Torch singer

Helen Morgan: Torch singerHelen Morgan was born in Canada in 1900. After her family moved to Illinois, she started her singing career at age 12. She was so small that she had to sit on a piano to be seen by the audience. At 18, she was crowned Miss Illinois, won $1,500 in a second beauty contest in Canada and moved to New York to study opera.

Working as a singer in speakeasies during Prohibition, first in Chicago, Morgan made her breakthrough in 1924 in New York when show producer Billy Rose (associated with mobster Arnold Rothstein) had her headline in his classy speakeasy, the Backstage Club.

She soon became famous for sitting atop a piano while singing “torch songs” about sad romances with men. She was cast in revues on Broadway, and in one, Americana, from 1926 to 1927, she sang the torchy “Nobody Wants Me” perched on a piano in the orchestra pit. Another huge break followed when she won the part of Julie in the debut on Broadway of the Florenz Ziegfeld-produced musical Show Boat in 1927.

Billy Rose’s Backstage Club, a tiny, charmless nightery over a garage on West 56th Street in New York. With Prohibition now in full force, the club was often raided by the minions of New York’s administrator for Prohibition, Maurice Campbell, until Rose accepted an offer from two mobsters to take them on as partners, thus assuring that the right palms were greased and the club was left alone.

Rose closed the club after six months, but during Morgan’s time there, she came under the protective eye of the mob and forged the links with New York’s raucous night life that would connect her with three of the city’s most popular clubs—Helen Morgan’s 54th Street Club, Chez Morgan, and Helen Morgan’s Summer Home.

She opened her own speakeasy that year, the Fifty-Fourth Street Club, at 231 West 54th Street, but the feds padlocked and closed it. In 1928, while at a new club, Helen Morgan’s Summer House, another arrest led to a trial but the jury acquitted her. More professional success followed. In 1929, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II (writers of Show Boat) wrote a Broadway show for her to star in, Sweet Adeline. She starred in the movie Applause that year and in Roadhouse Nights in 1930. Several records she recorded were national hits, such as “Why Was I Born?” and “Body and Soul.”

After Prohibition ended in 1933, Morgan’s career endured with performances on national network radio shows, starring roles in the movies Sweet Music in 1935 and Frankie and Johnnie in 1935 and a full sound movie version of Show Boat in 1936. But behind the scenes, she battled alcoholism.

In 1941, while on stage in Chicago, performing in Scandals of 1942 (a version of which she played on Broadway in the 1920s), she collapsed and later died of liver and kidney aliments. She was 41.

In later years, when asked what had made her so successful, Morgan would reply simply, “Hunger.”

Other blog posts in the Hooch ‘n Hellraisers series:

Hooch ‘n HellraisersWhiskey WomenQueens of the SpeakeasiesTexas GuinanBelle LivingstoneComing soon….

Hoochie-Coochie Hooch Haulers

The post HELEN MORGAN appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

March 6, 2022

WHISKEY WOMEN

Every woman can find lasting romance—even the lady moonshiner if a man loves her still.

Distilling used to be considered women’s work, part of their duties around the hearth and home. During the 1920s, the kitchens of widows and enterprising homemakers buzzed with activity as these self-reliant women made and sold alcoholic beverages so they could work at home while caring for their children.

Distilling used to be considered women’s work, part of their duties around the hearth and home. During the 1920s, the kitchens of widows and enterprising homemakers buzzed with activity as these self-reliant women made and sold alcoholic beverages so they could work at home while caring for their children.

Come along and meet a few of these moonshining women…

Texanna ChappellTexanna Chappell, a Virginia mother with six children, became a widow when her husband died suddenly. At his funeral, a relative told Chappell that many people were earning money as alky cookers and she could, too. Later, the helpful relative sent her a recipe for making corn whiskey. On day when Chappell’s children were crying due to hunger, she decided to become an alky cooker. She bought the components for a still, assembled it herself, and set it up in her home. She was afraid to fire up the still because she was nervous and apprehensive about breaking the law. But she calmed down, made her first batch and sold it to a neighbor who bootlegged.

“With that first money, I gave a party for the youngsters. We had chicken, and ice cream and cake, and everything that the kids could think of.”

After Chappell had been making alcohol for several months, acquaintances told her that the police were planning to raid her house. She disposed of her mash, dismantled her still, and poured all her whiskey down the drain.

“I’ve turned many a widow woman loose and never made a report. I did it because…her children would have had no food.” J. Cate, head of the federal Prohibition unit in East Tennessee.

Brewing illegal liquor provided income for a surprising number of older women who urgently needed money, usually to deal with family troubles. The enterprising seniors showed remarkable strength and fortitude as they carved out a niche in a cutthroat business run by mobsters. Judges sometimes sent older women to prison, which may have been a blessing in disguise for the frail, elderly ladies who struggled to keep the wolf from the door.

Rosa FontanaProhibition agents caught Rosa Fontana, age eighty-three, making and selling wine. She was a fragile, doddering woman who needed help to walk. She claimed she was making medicinal wine for her gravely ill husband. The couple had run a profitable grocery store, but his illness had depleted their savings, leaving them penniless. Following Rosa’s third arrest, she pled guilty to manufacturing and selling liquor and was sent to Alderson prison.

Marie Hoppe

Marie Hoppe

Acting on a tip from a group called the Volstead Vigilantes, Prohibition agents in New Orleans raided widow Marie Hoppe’s home, where they seized 130 bottles of homemade beer.

At Hoppe’s arraignment she told the judge that beer was a healthy, nutritious drink “Vital for a child’s muscle development.” The judge believed she was selling her homebrew so ordered her held for trial. Sadly, the widow died before her trial, leaving her children orphaned.

A woman did not have to live in a city or town to benefit from the underground liquor trade that Prohibition created. Female homesteaders, both married and single, supplemented their farm incomes with bootlegging.

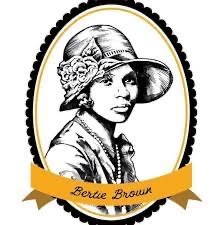

Birdie Brown The rutted road was a familiar one to Fergus County locals during the days of Prohibition. You had to be careful — bad hooch could cause blindness and even death. Those looking for a place to party knew to point their cars toward Black Butte and Birdie (or Bertie) Brown’s place.

The rutted road was a familiar one to Fergus County locals during the days of Prohibition. You had to be careful — bad hooch could cause blindness and even death. Those looking for a place to party knew to point their cars toward Black Butte and Birdie (or Bertie) Brown’s place.

Bertie (Birdie) Brown was among a very small number of young African American women who homesteaded alone in Montana. She was in her twenties when she settled in the Lewistown area in 1898. She later homesteaded along Brickyard Creek in 1913.,

Brown described herself at different times as an abandoned woman and as a widow. Like many women homesteaders, she supplemented her income in various ways. She raised leghorn chickens, kept a garden, and planted wheat, oats, and barley on twenty-five acres of her homestead. She is, however, best remembered for her moonshine.

She was as nice a woman as they come, and her still — according to locals — produced some of the best moonshine in the country.

During Prohibition in the 1920s, Birdie carved a niche for herself. Her neat homestead where she lived with her cat was a place of warm hospitality. Birdie’s parlor was legendary.

In May 1933, just months before the end of Prohibition and Birdie’s livelihood, the revenue officer came around and warned her to stop her brewing. But as Birdie multitasked, dry cleaning some garments with gasoline and tending what would be her last batch of hooch, the gasoline exploded in her face. She lived a few hours, long enough to request that someone take care of her beloved pet. But the cat that followed her everywhere was never found.

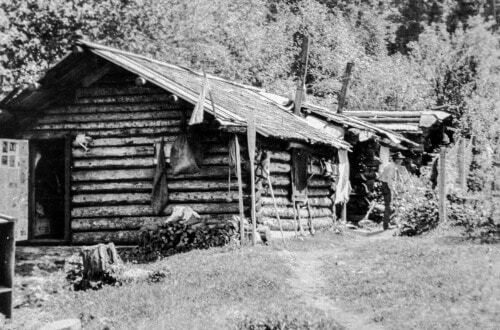

Josephine Doody Perhaps the most fantastic story of a homesteading bootlegger is that of Josephine Doody, a former dance-hall girl who brewed moonshine at her remote cabin on the southern edge of Glacier National Park.

Perhaps the most fantastic story of a homesteading bootlegger is that of Josephine Doody, a former dance-hall girl who brewed moonshine at her remote cabin on the southern edge of Glacier National Park.

According to the legend, Doody’s future husband, Dan, a ranger at the park, had met and fallen in love with Josephine after seeing her at a dance hall in the railroad town of McCarthyville. Wishing to rid her of her opium habit, Dan tied Josephine to his mule, took her to his homestead, and locked her up to break her addiction. After Dan died in 1919, Doody remained at the homestead and became famous for her moonshine.

In the early 1900s, Doody earned the nickname the “Bootleg Lady of Glacier Park” and she operated at least three stills in the wilderness north of Nyack.

Legend has it her shine was so good it would stop Great Northern Railway trains right in their tracks.

“[T]he train would stop at Doody siding, and each toot of the whistle would mean one gallon of moonshine. Josephine delivered it across the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in a small boat.”

At the peak of her reign, trainmen would help Doody distribute her product along the line and in return a bottle or two would end up in the engineer’s grip for his own enjoyment after a long day on the high iron.

Doody died of pneumonia in 1936.

Doody died of pneumonia in 1936.

Other blog posts in the Hooch ‘n Hellraisers series:

Hooch ‘n HellraisersComing soon….

Hoochie-Coochie Hooch HaulersQueens of the SpeakeasiesBelle LivingstoneTexas GuinanHelen Morgan

The post WHISKEY WOMEN appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

HOOCH ‘N HELLRAISERS

This blog post originally ran in The Old Shelter.

Imagine you are a woman living in the 1920s. You’re the sole breadwinner- perhaps your husband came back from the Great War injured and unable to work… or perhaps he didn’t come home at all and you were left alone, raising a passel of kids. Worried about a roof over your head and food on the table.

What would you do?

Or maybe you are one of those enterprising women who wanted something different in life, defying social conventions and family expectations. Carving out a little piece of the American dream for yourself- for fun and profit.

What could you do?

In either case, and for hundreds of women during the 1920s, they recognized an economic opportunity when America embarked on its great social experiment- making liquor illegal. True to form, when anything is banned, human nature takes over and demands more of it. Prohibition did much to help women make a very good living.

I write historical fiction set during Prohibition. The central characters in my novels are all women with more than a passing acquaintance with the dangerous criminal world of illegal hooch- making it, selling, drinking, or cleaning up the aftermath. Jennie Justo runs a speakeasy in Wisconsin, Maggie Barnes is a widow in Philadelphia trying to raise her son in a city that has become a bootleggers’ playground, Edith Duffy builds a rum running empire out of a nightclub just outside Miami, Delores Bailey is a cranky moonshiner in the backwoods of Montana, and Lucie Santoro is a spinster schoolteacher originally from New York City who enjoys a wee tipple in the evening, putting her career and reputation on the line with every sip.

One of the most strictly gendered activities in the United States in the decades prior to Prohibition was the consumption of alcohol, specifically alcohol, purchased in bars, clubs, and saloons.

Prior to Prohibition, in many states in America, women were barred from entering drinking establishments. Nor could they work in any place that sold alcohol, or that was even next door to establishments that sold alcohol of any kind. Women were seen as strictly domestic-bound beings and the restrictive laws a necessary enforcement of good morality. These laws also meant that the only women culturally “allowed” to enter drinking establishments were entertainers and prostitutes.

Prohibition changed all that. The fact that speakeasies, for example, were illegal meant that for the first time in American history, women could walk in and order a drink. The times encouraged social taboos to be broken with alcohol no longer a man’s-only fare. Thanks to Prohibition, it wasn’t only women of bad reputations who were able to enjoy strong drinks and dancing with boys.

And ironically, even though mothers and grandmothers had been busy trying to protect youth by organizing to pass statewide Prohibition prior to the 1920s, their own daughters were the ones who rejected that law in every regard—contributing to a level of female-led crime never before seen in America and providing a ripe environment for story tellers like myself.

Woman had an advantage over men when it came to moonshining- rum running- bootlegging.

For starters, they were much harder to detect and arrest than men simply because it was illegal to search a woman in those days. Women took full advantage of this and actually hid moonshine on their persons; some even taunted law enforcement to search them. Also in their favor was the fact that juries of the day were loath to convict a woman of the crime of bootlegging. They simply refused to believe that a woman could do such a thing.

Many times, male bootleggers would hire women to ride along with them on their moonshine deliveries because they knew the police were less likely to stop them with a woman in the car. The word on the street was that no decent federal agent would hold up a car that had women in it.

The enterprising women who thrived in making or peddling hooch during Prohibition were a very diverse group- from the widow who brewed in her kitchen so she could purchase Easter outfits for her five children, to the eighty-year-old grandmother who was caught running a three-hundred-gallon still.

Because many bootlegging operations were family affairs, children often participated as well. Helen McGonagle Moriarity recalled her role in her mother’s liquor trade, which was cleverly paired with her existing laundry business. Moriarity’s mother, Mary Ann, washed for miners living in a boardinghouse. As a teenager, Helen delivered booze hidden among the clean clothes for “fifty cents a pint and two dollars a gallon.”

There was the young mother and her small child who were taken to the matron’s quarters of the city jail, where she awaited charges of violating prohibition laws. State Prohibition agents had raided her home after she sold one of them a bit of wine the night before, and several gallons were confiscated. Nobody else was ever arrested for the illicit wine, pointing to the possibility that she was a single mother who sought financial security in black-market wine within her community.

There was the young mother and her small child who were taken to the matron’s quarters of the city jail, where she awaited charges of violating prohibition laws. State Prohibition agents had raided her home after she sold one of them a bit of wine the night before, and several gallons were confiscated. Nobody else was ever arrested for the illicit wine, pointing to the possibility that she was a single mother who sought financial security in black-market wine within her community.

And the young mother’s story is typical. Most female bootleggers participated in small-scale, personally run operations and sold their wares locally. Making the family’s homemade wine and beer was a skill that had been passed from mother to daughter over generations. As long as a woman had access to a kitchen, she had the ability to make booze. Many women took advantage of the Prohibition black market to operate small-scale enterprises out of their homes known locally as pocket-stills or beer-flats.

Women also saw success peddling booze. One enterprising woman who owned a boardinghouse in was caught selling alcohol to her patrons. Her record book showed that for the previous few weeks, her salary had averaged $150 per day. In 1924, the average (white male) yearly income in the country was around $1,300, so a woman making that much in two weeks through illegal alcohol production points to a lucrative black market.

There are also numerous examples of women-led business empires built on manufacturing and smuggling illegal alcohol on a larger scale. These early female entrepreneurs were limited by access to start-up capital, however, their brains and risk-taking natures encouraged them to flourish. In my Rum Runners series, the fictional heroine teams up with two very real historical women who were the queens of offshore smuggling in Florida during the 1920s.

Changes in technology during the 1920s boosted women’s access to many new economic and social opportunities, including those around alcohol. The automobile redefined rituals of dating and courting, allowing many young and/or rural people to see each other outside the careful eyes of chauffeurs or parents. They also provided women with mobility and a means to transport their illegal hooch.

New fashions in the 1920s lent themselves to clever ways to smuggle alcohol. Women with freshly bobbed haircuts could spend their evenings dancing the Charleston in dance halls and speakeasies, sneaking in flasks of liquor on garter belts, under oversized fur coats, or in avant-garde styles of skirts and blouses.

The thirteen years of Prohibition gave American women the opportunity to redefine their social place in the world through their participation in illegal alcohol manufacturing, transportation, commerce, and consumption.

Barely four years into Prohibition, journalist Jack O’Donnell described women bootleggers. They “come from all stations and ranks of life—from the slums of New York’s lower East Side, exclusive homes in California, the pine-clad hills of Tennessee, the wind-swept plains of Texas, the sacred precincts of exclusive Washington.”

Continuing, “Some are bold, brainy and beautiful, some hard-boiled and homely, some white, some black, some brown. All are thorns in the sides of Prohibition Enforcement officials.”

Oh, how right he was.

Other blog posts in the Hooch ‘n Hellraisers series:

Whiskey WomenComing soon….

Hoochie-Coochie Hooch HaulersQueens of the SpeakeasiesBelle LivingstoneTexas GuinanHelen Morgan

The post HOOCH ‘N HELLRAISERS appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

October 5, 2021

Cosmetics: Safer, Handier, and Sexier

This guest post is by writer and blogger Sarah Zama. “Ghosts Through the Cracks” is her first publish novella. She’s also published the history book Living the Twenties, a look at the 1920s as a global experience, organized in alphabetical order.

She’s currently working at more historical fantasy stories set in the 1920s, and more books about the 1920s historical experience.

From the 1890s to the 1910s, Charles Dana Gibson created a series of illustrations that became the epitome of the Edwardian girl. They depicted feminine beauty as it was most appreciated at that time, girls who were as pure and ethereal as angels, whose looks were naturally elegant.

But at the beginning of the 1920s, the angelic Gibson Girl turned into the daring Flapper Jane… trouble ensued.

The Gibson Girl: the angelic queen of purity Nice girls didn’t wear makeup still well into the 1910s – or paint, as it was then referred to, in case anyone missed the fact that it was bad. That kind of artificial beauty was used only by women who pursued a goal and led questionable lives: prostitutes, dancing girls, and movie stars.

Nice girls didn’t wear makeup still well into the 1910s – or paint, as it was then referred to, in case anyone missed the fact that it was bad. That kind of artificial beauty was used only by women who pursued a goal and led questionable lives: prostitutes, dancing girls, and movie stars.

The Gibson Girl didn’t need anything to enhance her beauty. That, it was implied, came from her demeanour and education, as well as her face and body. Men believed–or wanted to believe, or preferred to believe, or were led to believe–that their girls didn’t wear any makeup and their beauty was natural. Artificiality was most abhorred, especially where women were concerned.

The Gibson Girl was eager to use any trick available to her to enhance her appearance–but in secret, and only to a certain extent. Cosmetics vendors did abound, and beauty books were also available to teach how a girl could look beautiful without being artificial. A girl only had to use them wisely.

Besides, cosmetics differed greatly from paint. Paint was supposed to create an artificial illusion of beauty, whereas cosmetics would make a woman’s natural beauty glow, especially by highlighting the health and looks of her skin.

Like any woman in any era, Victorian women made good use of what little they were allowed. Powders, bases and waxes of very light colours were quite easily available, as well as the cold creams used to remove them. There was only one problem: cosmetics–not to mention paint–were dangerous.

Most of them contained toxic substances that could damage a woman’s health. Even the widely used whiteners, which made the skin look fairer and were therefore very popular, contained such dangerous substances. But this was true for many other cosmetics of the time. And anyway, cosmetics–paint even more so–were a mess to use and not very clean or precise.

So Gibson Girls were advised to use as little cosmetics as possible and instead take advantage of any trick. For example, beauty books of the era suggested biting their lips and pinching their cheeks vigorously before entering a room. Maybe not as effective as paint, but surely safer.

I’m beautiful, let me show it off

Then, as the 1910s turned into the 1920s, a few things happened.

Cosmetics became safer and easier to use, not as fussy, more precise and even portable, as the compact and the lipstick entered the market. And at the same time, youths’ attitudes toward makeup changed radically.

The freer interaction between the sexes made sex appeal much more important. Young people no longer looked for just a wife or a husband in their partner. They wanted a companion, and they wanted to choose them. This made the competition ferocious on both sides. Because free choice became so much more critical in the peer group, attracting attention became likewise crucial.

Make-up was a new tool in this new game where every girl became a star.

The popularity of movies exploded in the 1920s. Many films depicted the everyday lives of the new youth, thus becoming a complex game of mirrors, where fiction mimicked reality and reality ran after fiction. Young men and women saw themselves in those young actors and actresses who did what every young person did, but more intensely. Those young stars whose presence was pervasive in magazines and ads became the model–both in behaviour and look–for the new youth.

There was a very practical reason why actresses used makeup: it accentuated their features ‘on screen’, something necessary in the black and white era. That kind of makeup existed specifically to highlight their eyes and lips, and therefore their expressivity on screen, but it soon turned into a model for young girls who wanted to express themselves at their best and for young men who looked for just the special girl. Young people looked at their favourite celebrities to define beauty and learn how to enhance their sex appeal. It was a completely new way to understand and express themselves.

Flapper Jane: the stubborn pursuer or self-expression

Flappers were famous for applying lipstick and powder in public. Scandalous as this was before the 1920s, it now became fashionable and daring because of the sexual underline implied in the enhancement of sex appeal. It was a clear message that a woman had every right to use her looks to communicate her essence. This communication wasn’t entirely free from the pressures of the new consumers’ society, yet it broke sharply with any past convention.

The way young women used freely what was once considered scandalous and vulgar gave rise to a lot of protest from more conservative observatories who cried out for the lost purity of women. Such free use of cosmetics looked decadent to them. In fact, like many other new activities of the 1920s youth, it was carefully kept in check by the peer group.

It was the peer group that determined what was tasteful and what was excessive. Wearing makeup and even applying it in public was generally acceptable, but using too much or ignoring the etiquette distinguishing day from night makeup was normally sanctioned. Girls who exceeded in the use of makeup were made fun of. Slowly, a common ‘code of conduct’ took shape, which dictated what was acceptable, a code not imposed by elders, but one that youths created themselves.

It was just a matter of time before older women, then society at large, accepted makeup as normal in a woman’s life.

It was just a matter of time before older women, then society at large, accepted makeup as normal in a woman’s life.

The Twenties were the death of paint and the birthplace of makeup.

Other guest posts by Sarah Zama on Sherilyn Decter’s Bootlegger blog:

Shameless, Selfish and Honest – The changes in society that allowed the coming of the New Woman

The post Cosmetics: Safer, Handier, and Sexier appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

September 7, 2021

Shameless, Selfish, and Honest

This guest post is by writer and blogger Sarah Zama. “Ghosts Through the Cracks” is her first publish novella. She’s also published the history book Living the Twenties, a look at the 1920s as a global experience, organized in alphabetical order.

She’s currently working at more historical fantasy stories set in the 1920s, and more books about the 1920s historical experience.

In many respects, the Twentieth century started with WWI. It was a time that brought incredible change in life and society. It can be said that WWI (the Great War, as it was called throughout the first half of the century) truly destroyed many ways of thinking and behaving that still belonged to the Nineteenth century.

From its ashes, a new way of living and thinking was born. The 1920s – The Roaring Twenties as they were known in the US – was the first place where that change became apparent. Nowhere more so than on people’s personal life.

A New Era

It didn’t happen overnight. It didn’t even happen during the four years of war. The way people perceived themselves and their lives had already started to change in the Nineteenth century. People had long tried to gain control over their lives to mould it in the way that most satisfied them. Middle-class families were particularly sensitive to this matter. Already in the Nineteenth century, these families had started using birth control (whatever was available at the time) to become smaller units and to gain the time necessary to pursue personal goals. But at that time, effective birth control was very limited, so couples had to resort to avoidance to limit births. This accounts for both the widespread practice of late marriages in the middle class and the Victorian obsession with avoiding any sexual thought or hint.

It didn’t happen overnight. It didn’t even happen during the four years of war. The way people perceived themselves and their lives had already started to change in the Nineteenth century. People had long tried to gain control over their lives to mould it in the way that most satisfied them. Middle-class families were particularly sensitive to this matter. Already in the Nineteenth century, these families had started using birth control (whatever was available at the time) to become smaller units and to gain the time necessary to pursue personal goals. But at that time, effective birth control was very limited, so couples had to resort to avoidance to limit births. This accounts for both the widespread practice of late marriages in the middle class and the Victorian obsession with avoiding any sexual thought or hint.

At the beginning of the Twentieth century, contraception became more reliable, more common, and especially more widely accepted. Couples now had the means to decide when they wanted to have children and how many of them they wanted. This produced the hoped-for obligation-free time necessary to pursue personal aspirations. It also produced an unexpected effect that proved to be among the biggest social earthquakes the Western World had ever known.

The New Youth

The New YouthThe family, this most important staple of society, changed completely. Because families became smaller, all their members had more manoeuvring space inside it, more quality time to spend with each other. Where the Victorian family – numerous as it tended to be – needed to be managed and so every member had – first and foremost – a role to perform, the new smaller family would afford to care about its few members. Relationships inside it hinged not on roles, but on affection. And this caused an epochal change in the relationship between husband and wife and between parents and children.

Freed from the preoccupation of having children when they were still not ready for it and given the opportunity to plan when to have them, couples could get together at a younger age. They could then create a companionable relationship, get in the desired economic position and even finish pursuing an education before they actually build a family.

Having time for themselves allowed these couples to give more attention to their partner’s personality and desires. When they had the children they wanted (rarely more than three), they could give these children the same kind of attention and affection.

These parents, who had sought their own personal fulfilment, were just as eager to give their children a chance to get their fulfilment before life started becoming demanding. They were willing to sustain the cost of child-rearing longer than any generation before them, thus affording their children to be young and free of adult responsibilities for a longer time.

These parents, who had sought their own personal fulfilment, were just as eager to give their children a chance to get their fulfilment before life started becoming demanding. They were willing to sustain the cost of child-rearing longer than any generation before them, thus affording their children to be young and free of adult responsibilities for a longer time.

On the other hand, these children – who came of age in the 1920s – were willing to remain dependent on their parents for a longer time, a result of the desire to pursue their own desires as well as of the new affectionate family. This is how the concept of youth as we conceive it today was born.

The new, affectionate family who planned their life and when to have their children brought about a huge change, especially in women’s lives.

The new, affectionate family who planned their life and when to have their children brought about a huge change, especially in women’s lives.

Intercourse with a man had always been likely to get a woman pregnant whether she (or they) wanted it or not. Especially in the Victorian Age, when the need to plan a family became relevant, but the means to do it were still few and ineffective, a woman’s sexuality had simply been denied. Women were seen as pure and free from the sexual impulses that characterised men and were even expected not to take pleasure from sex.

When reliable contraception allowed couples to have intercourse without a pregnancy, if they so decided, it was women who were liberated first and foremost. Now they could live their sexuality in a freer, more joyous way, not unlike men. Physical attraction, as well as spiritual affinity, became very important in the formation of couples. Women were no more expected to be merely mothers. They became companions, lovers, wives and mothers. The search for the perfect partner who would be a mate and a life companion led to the practice of dating. Men and women got together for a time without the pressure of marriage. Personal attraction increased in importance. For women, this meant displaying their sexuality and sex appeal freely in a way that was socially acceptable for the first time in centuries.

In response to this, women’s social position also changed. To become a companion for her man, the New Woman needed to gain all the characteristics a shared life demanded in everyday and couple life. Men no more looked merely for a mother for their children. They also wanted a companion to share their life experience, and women were ready to be just that.

Because the change was so shocking on the women’s side, we tend to think that’s the only change that happened.

But the shift in thinking and accepted social behaviour that allowed the New Woman to be born actually started with her parents. Also, the inner drive that moved the New Woman was the same for her male counterpart. They wanted to express themselves freely and be free to make their own choices.

Sure, there was great, sometimes loud controversy surrounding the New Woman. Yet, some of her behaviours were accepted by all women, including their mothers.

Their male counterparts accepted their behaviour because it matched young men’s behaviour and desires. The New Woman wanted to be free to express herself, choose a partner for her life, and pursue her desires both in terms of personal and career life.

These were the same things young men wanted.

The New Look The New Woman’s new look isn’t just the expression of a woman’s newfound freedom, and it certainly isn’t just a matter of fashion. It’s the expression of a change that involved an entire society, regardless of gender and age.

The New Woman’s new look isn’t just the expression of a woman’s newfound freedom, and it certainly isn’t just a matter of fashion. It’s the expression of a change that involved an entire society, regardless of gender and age.

In the ways the New Woman’s body changed and the ways she used that body, we can trace the values and behaviours of an entire society and age.

[image error] Sarah Zama Bio

Born and raised in Verona (Italy), Sarah Zama has always lived surround by books, so it may be a sort of karma that she ended up being a bookseller and an indie author. A fantasy reader since a kid, a Tolkien nerd almost as long, she’s always being fascinated with history and old black-and-white mystery films, which may or may not have had a way in her involvement in the dieselpunk community.

“Ghosts Through the Cracks” is her first publish novella. She’s also published the history book Living the Twenties, a look at the 1920s as a global experience, organized in alphabetical order.

She’s currently working at more historical fantasy stories set in the 1920s, and more books about the 1920s historical experience.

CONTACT INFO AND LINKS

Email: oldshelter@yahoo.com

Blog: www.theoldshelter.com

Website: https://sarahzama.theoldshelter.com/

SOCIAL MEDIA:

Twitter: www.twitter.com/JazzFeathers

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/jazzfeathers

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jazzfeathers/

Pinterest: https://it.pinterest.com/jazzfeathers/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SarahZamaAuthor/

BookBub: https://www.bookbub.com/profile/sarah-zama

Medium: https://medium.com/@JazzFeathers

The post Shameless, Selfish, and Honest appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

October 30, 2020

Eleanor Roosevelt: The Activist

[image error]Hi there- Bette Hardwick here from sometime in the 1920s with the last installment of the four-part series on Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of New York Governor Franklin Roosevelt.

There was a lot to tell, so I’ve divided my notes up into four parts: Childhood, School, Early Marriage, and Political Activism.

A Political Life

[image error]A significant change occurred for the Roosevelt’s in 1911 when Dutchess County elected Eleanor’s husband to the New York state senate. Franklin asked her to leave New York City and to set up a home for the family in Albany.

“For the first time, I was going to live on my own. I wanted to be independent. I was beginning to realize that something within me craved to be an individual.” ER

Eager to leave the vigilance of her mother-in-law, Eleanor tackled the move with enthusiasm and discipline.

By the time Franklin left Albany to join Woodrow Wilson’s administration two years later, Eleanor had begun to view independence in personal and political terms.[image error]

“That year taught me many things about politics and started me thinking along lines that were completely new.” ER

Franklin Roosevelt has said, “Albany was the beginning of my wife’s political sagacity and co-operation.”

Consequently, when her husband was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy in autumn 1913, Eleanor knew most of the rules by which a political couple operated.

“I was really well schooled now. . . . I simply knew that what we had to do we did, and that my job was to make it easy.” “It,” was whatever needed to be done to complete a specific family or political task.

[image error]As Eleanor oversaw the Roosevelts’ transitions from Albany to Hyde Park to Washington, coordinated the family’s entrance into the proper social circles for a junior Cabinet member, and evaluated Franklin’s administrative and political experiences, her independence increased as her managerial expertise grew.

When the threat of world war freed Cabinet wives from the obligatory social rounds, Eleanor, with her commitment to settlement work, administrative skills, disdain for social small-talk, and aversion to corrupt political machines, entered war work eager for new responsibilities.

World War I

[image error]The war gave Eleanor an acceptable arena in which to challenge existing social restrictions and the connections necessary to push forward reform.

Anxious to escape the confines of Washington high society, Eleanor threw herself into wartime relief with a zeal that amazed her family and her colleagues. Her fierce dedication to Navy Relief and the Red Cross canteen not only stunned soldiers and Washington officials but shocked Eleanor as well.

“I became more determined to try for certain ultimate objectives. I had gained a certain assurance as to my ability to run things, and the knowledge that there is joy in accomplishing good.”

Eleanor began to realize that she could contribute valuable service to projects that she was interested in and that her energies did not necessarily have to focus on her husband’s political career.

Emboldened by these experiences, Eleanor began to respond to requests for a more public political role. When a Navy chaplain whom she had met through her Red Cross efforts asked her to visit shell-shocked sailors confined in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, the federal government’s facility for the insane, she immediately accepted his invitation.

Appalled by the quality of treatment the sailors received, as well as the shortage of aides, supplies, and equipment available to all the St. Elizabeth’s patients, Eleanor urged her friend, Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane, to visit the facility. When Lane declined to intervene, Eleanor pressured him until he appointed a commission to investigate the institution.

Spouse of the Candidate

[image error]In June 1920, Franklin received the Democratic nomination for Vice-President. Although both her grandmother and mother-in-law strongly believed that “a woman’s place was not in the public eye” and pressured Eleanor to respond to press inquiries through her social secretary, she developed a close working relationship with her husband’s intimate advisor and press liaison, Louis Howe.

[image error]

Invigorated by Howe’s support, Eleanor threw herself into the election and reveled in the routine political decisions that daily confronted the ticket. By the end of the campaign, while other journalists aboard the Roosevelt campaign train played cards, Louis Howe and Eleanor could frequently be found huddled over paperwork, reviewing Franklin’s speeches and discussing campaign protocol.

The Republican candidate won the ticket that year, and the Franklins returned to Albany.

Back into the shadows

Eleanor was not thrilled with the prospect of returning to Albany and the governor’s mansion. It was a goldfish bowl in which all her movements would be both confined by and interpreted through her husband’s political prestige.[image error]

She told her son James that “she knew that Franklin would expect her to move into the shadows as he moved into the limelight.” This shift depressed her immensely. Various people have said that Eleanor’s “dread” of returning to the shadows was so strong that it fostered a rebellion which “strained at the leash of her self-control.”

However, Eleanor also realized that her political expertise and her new support system provided new opportunities she hadn’t had previously. Instead of becoming a compliant helpmate, she concentrated on how to find the most appropriate manner to promote two careers at once. Eleanor sought ways to pursue her separate interests so that they did not undermine her husband’s public standing.

She knew how threatening this would be to some pundits. So, immediately after the election, Eleanor launched a media campaign to make the press treat her various activities in the most positive light possible.

Franklin’s struck with polio

Tragedy struck Eleanor’s life again when Franklin contracted polio in 1921.

With her husband incapacitated and undergoing intensive treatment, Eleanor began serving as a stand-in, making public appearances on his behalf, often carefully coached by Louis Howe.

[image error]

She also started working with the Women’s Trade Union League(WTUL), raising funds in support of the union’s goals: a 48-hour work week, minimum wage, and the abolition of child labor.

Eleanor was also very active in The Women’s City Club of New York. It kept women informed of political issues of the day and offered members a network of fellow professional women.

Within three years of joining this organization, Eleanor Roosevelt would be elected to the board and then first vice president. She became the club’s literal voice, initiating her career in radio with broadcasts intended to make women listeners informed on current political issues affecting them.

Some of the public questions that she encountered included government low-income housing, access to birth control information for married women, child labor regulation, worker’s compensation, and protective measures for working women. Her work with the Club helped develop her own organizational, writing and speaking skills.[image error]

Throughout the 1920s, through these initiatives and others, Eleanor became increasingly influential as a leader in the New York State Democratic Party while Franklin used her contacts among Democratic women to strengthen his standing with them, winning their committed support for the future

There are rumors that Franklin is considering a run at the White House. More information about Eleanor’s life and her husband’s political career can be found on The Bootleggers’ Chronicles and online.

[image error]

The post Eleanor Roosevelt: The Activist appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

August 16, 2020

Isdell Mercantile, Pony Montana

[image error]Hi there- Bette Hardwick here from sometime in the 1920s. You know…Sherilyn’s Gal Friday.

I pulled a bit of research off Sherilyn’s desk. She’s writing a series set in Montana in a small mining town called Pony Gulch.

Now, Pony Gulch is actually a real place so there are lots of archival photos, reference books, and oral histories for her to rely on as she builds the fictional world for her books.

Here are a couple of photos of Isdell’s Mercantile, in Pony, Montana, right there on Broadway Street.

[image error]The modern photo shows the condition of the building now.

[image error]

This archival photo was taken in the late 1800’s, about thirty years before the 1920s when the Moonshiner Mysteries series is set.

The Mercantile was established in 1869 with the motto “We sell everything from a toothpick to a house…”, which is a line I’m sure Sherilyn is going to use somewhere in the series.

The Isdell Mercantile Company (IM Co.) was created in 1869 by N. J. Isdell in the town of Pony, Montana. Once called the “metropolis of the Madison Valley” by the Madisonian, Pony was a boom town created by major quartz discoveries in 1875. The mercantile was incorporated in 1892. By 1900 the town had a schoolhouse, bank, newspaper, hotels, and several saloons.

This growth, made possible by wealth from local mining operations, allowed the small store to prosper. The Isdell Mercantile provided hardware, mining supplies, and various dry goods to the community. The town, which once had a population over 1,000 in 1900, currently has less than 200 people. The mercantile went out of business when the quartz mining was halted in the Pony area.

Mr. Isdell was a prominent Pony businessman, civic leader, and founder of the once-prosperous Isdell Mercantile Company that had stores across Montana.

Some might think it sad to see the dreams and ambitions of a man now crumbling, but they will live on in some form with the characters and places in Sherilyn’s books. That’s why she takes such care in making them as accurate as she can, given she’s writing fiction. It’s a tribute to those that came before—whether buildings in Philadelphia (Bootlegger series), Florida (Rum Runner series), or Pony, Montana (Moonshiner series.)

I peeked over her shoulder while she was writing the scene where Delores Bailey (the moonshiner) comes into the Mercantile for the first time.

[image error]

“Isdell’s Mercantile smelled of sugar, wool, and leather. Shelves held copious items, including shoes, work boots, overalls, stationery, soaps, polish, and home items such as kitchenware and lanterns. Wooden barrels were filled with taffy, salt crackers, rice, and anything else one could need. In the corner nearest the counter, a shiny black Singer sewing machine was on display. Mr. Isdell was with a customer, so I occupied myself by scanning the rolls of fabric on the shelf behind her. There were several heavy wools: a forest green, dark blue, charcoal gray, and black. After the man left, Mr. Isdell bustled over, wiping his hands on his shop apron and asked what he could do for me.”

I’m sure there will be a few other research tidbits falling off the corner of Sherilyn’s desk (I’m not snoopy- just curious!) that I’ll be sharing with you.

Oh, and before I go, Sherilyn would want me to mention that there’s a very active group of Pony residents working hard to preserve their history. Right now they’re working on saving the school roof. It’s a big responsibility as there are so few folks living in Pony anymore, but what they lack in numbers they make up for in grit and heart. You can check them out here at the Pony Homecoming Club.

The post Isdell Mercantile, Pony Montana appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.

March 6, 2020

Miami: Mob City

[image error]Hi there- Bette Harwick here. I’m Sherilyn’s sidekick and gal-Friday from the 1920s. Which is another way of saying I’m her ‘unofficial’ research assistant. More like unpaid… but hey, it’s tough for a gal to get a break in this biz so I take any gig I can.

As you know, I’m a bit of a scribbler myself, and one of the things I enjoy is reading over Sherilyn’s notes at the end of the day. –although don’t tell Sherilyn, she hates it when I read her stuff before she’s finished polishing it.

I’ve noticed that the idea of Miami as a mob city has really caught her imagination. Everybody thinks of Chicago and New York as the home base for gangsters… but hey, those mob-bosses have to vacation somewhere, right?

The popularity of automobiles and the expansion of the railway opened up Florida. These days, Miami in the Twenties is in the middle of a frantic land boom as hundreds of thousands of tourists fall in love with the tropical paradise.

[image error]Like many of their fellow citizens, gangsters from all over America flock to the sun-kissed beaches to escape the cold and the snow. They trade in their suits and fedoras for swim trunks and flip-flops. I was playing at being a paparazzi when I snapped this pic of Al Capone in his swimtrunks.

There’s a hedonistic feel to any resort and when you have a whole city, a whole state turned over to making guests feel welcome, well that has some interesting consequences. Especially during Prohibition, the time period for the Rum Runners’ Chronicles.

In Miami, Fort Lauderdale and up and down Florida’s south coast, vice flourished. Newspapers refer to it as ‘Lansky-land’ in tribute to the influence of Meyer Lansky, the notorious New York crime boss who has sewn up much of the gambling in the state. Sherilyn has included him in the Rum Runners’ trilogy as a lurking, menacing figure (which sure as shootin’ he is!) and Edith’s eventual business partner.

[image error]Sherilyn also contrasts the relaxing calm afternoons on white sandy beaches with an exciting Miami nightlife. Edith recognizes the potential, as do those Yankee mobsters. Gator Joe’s and Goodtimes are part of the illegal speakeasy/ blind-tiger action.

Sherilyn also brings a real life Miami nightclub- Tobacco Road, to life. From her research notes, Tobacco Road (from Wikipedia) is a bar in the Brickell area of Downtown Miami, Florida. It was popularly known as the oldest bar in the city. The liquor license it amended was first issued in November 1912 (though property records show the building as being built in 1915, as a bakery) and operated nearly continuously since its opening, having been shut down briefly at times for run-ins with the law, such as when the upstairs, now a live music venue, was used as a speakeasy during Prohibition. Tobacco Road was located at 626 South Miami Avenue, on the south side of the Miami River. Tobacco Road celebrated its 100th anniversary in November 2012. In 2012, the land on which Tobacco Road lies was purchased for $12.5 million. On October 26, 2014, Tobacco Road closed and was demolished by Thunder Demolition Inc. An estimated 4,000 people came on its last night.

[image error]

There has been rapid and mammoth investment in nightclubs, casinos, race tracks, and slot machines. Illegal liquor is so available every hotel bellhop is a bartender. Orange groves and mango swamps are transformed into nightclubs, hotels and casinos. Sheriffs are given direction to make sure that this new energy of easy money ran smoothly.

If you’ve read any of the Rum Runners’ trilogy, you’ll recognize all these references. In fact- the bartender bell hop features prominently in Edith’s dialogue in the first book, Gathering Storm.

Mobsters from Chicago, Detroit, Philly, New York; they have all arrived en masse to put down business roots in Miami’s rich, fertile soil. Sharing territory, splitting the operations, and sharing the profits keep internal crime down and more importantly, draw little publicity. The spirit of cooperation that began with Nucky Thompson in Atlantic City allows crime families to flourish in Miami.

[image error]Al Capone, the unofficial mayor of Miami, has a sprawling mansion on Palm Island. One of the first things he did stepping off the train that first time was to drop by the real mayor’s clothing store and order a $1,000 of silk shirts, and thus a mutually beneficial partnership was born.

Of course, by the time Edith arrives on the scene in Miami, Capone was in prison for tax-evasion. That gave her and BFF Mae Capone a chance to spend some quality time together- looking at real-estate and building a bootlegging empire along the southwest Florida coast.

“The major port city of Nassau is built on ambition. It’s close enough to be America’s back door and, in these days of Prohibition, functions as a wine and spirits clearinghouse within the law.” Eye of the Storm, Book 3 Rum Runners’ Chronicles

Besides the nearly perfect year-round climate and enormous profits, Miami also provides convenient access to neighboring countries where the mob hold prosperous business interests. A short boat or plane trip and a mobster is in Cuba, the Bahamas, and other Caribbean islands where gambling was booming and liquor was legal.

[image error]Plane travel is a new thing in 1932, and in the books Edith, Mae Capone, Cleo Lythgoe, and Spanish Marie all make regular trips to Nassau. Being able to fly back and forth is a marvelous advancement.

There’s an important scene in the final book, Eye of the Storm, where young Leroy is inspired to become a ‘saloon-owning pro-baseball playing pilot’ based on his experience at the Miami airport.

I can see why Sherilyn’s so caught up in the idea of the vice that sweeps into Florida like a tropical storm. Of course, our heroine, Edith Duffy is in the middle of it, buying and running her little speakeasy Gator Joe’s, and the gorgeous club that rose from Gator’s ashes called Goodtimes.

Take it from me, if you like the idea of a cool-headed woman persevering in the dangerous business world of prohibition America, the Rum Runners’ Chronicles are for you.

They’re not just stories about Prohibition in America, at their core they’re about womanhood and strength.

The feeling I was left with when closing Gathering Storm, Storm Surge, and Eye of the Storm is one of steely determination and hope.

Click this link and start reading Gathering Storm’s Chapter One if you are looking for a female-led historical fiction with a backbone of steel.

The post Miami: Mob City appeared first on Sherilyn Decter.