Bathsheba Monk's Blog, page 12

March 5, 2014

March 4, 2014

Sex, lies and yoga

Published on March 04, 2014 10:09

March 3, 2014

We Have Lift Off!

Lots of legal and personal problems getting this story out there, but here it is! If you like yoga, mystery and the allure of love, you'll like this. Dead Karma now available on Kindle Select for 3.99. Not for the faint of heart.

Published on March 03, 2014 10:04

February 27, 2014

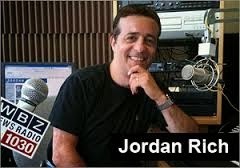

Why I love Jordan Rich of WBZ, Boston

http://swansoncozymysteries.com/why-i-love-jordan-rich-of-wbz-in-boston

http://swansoncozymysteries.com/why-i-love-jordan-rich-of-wbz-in-bostonClick here to get to my interview with Jordan Rich of WBZ Boston, one of my favorite people in the world.

While you're there, check out the Swanson Herbinko Cozy Mystery Series. I think you just might like it!

Published on February 27, 2014 12:21

February 26, 2014

Review of The Lego Movie

Published on February 26, 2014 07:45

February 19, 2014

Dead Karma--or why don't you shovel it yourself?

Since my new book Dead Karma is about to be published, I was thinking a lot about karma. What goes around comes around. Karma sticking to you so you have to get rid of it. A FB friend, the most unknowable kind, yesterday posted about a neighbor who didn't shovel his walk for the last couple of snowstorms and he can't walk his dog. I couldn't believe the number of people who weighed in on this: call the police! call code! Do something bad to him! The poster said that he assumed the person had a lot of money because he had a large house with a lot of sidelwalk--this is a very old neighborbood of a basically dilapidated town. Don't know. Can't you walk your dog somewhere else? Can't you do a mitvah and shovel the guy out yourself? I am extremely prejudiced in this because I live in a big house with a lot of sidewalk and I haven't been able to get out to shovel for the last 4 storms. Where's the karma?

Since my new book Dead Karma is about to be published, I was thinking a lot about karma. What goes around comes around. Karma sticking to you so you have to get rid of it. A FB friend, the most unknowable kind, yesterday posted about a neighbor who didn't shovel his walk for the last couple of snowstorms and he can't walk his dog. I couldn't believe the number of people who weighed in on this: call the police! call code! Do something bad to him! The poster said that he assumed the person had a lot of money because he had a large house with a lot of sidelwalk--this is a very old neighborbood of a basically dilapidated town. Don't know. Can't you walk your dog somewhere else? Can't you do a mitvah and shovel the guy out yourself? I am extremely prejudiced in this because I live in a big house with a lot of sidewalk and I haven't been able to get out to shovel for the last 4 storms. Where's the karma?

Published on February 19, 2014 08:02

February 17, 2014

DVD Binge Part II

Published on February 17, 2014 05:54

February 15, 2014

DVD Binge

Saw a lot of DVDs this week. Went to the library at 11 am the day of the storm and the very cool AV librarian at the Allentown Public Library told me I missed the rush and everything was picked over. Which actually turned out to be fine because what was left was pretty superb. Here's my reviews of three: Titanic, The Ice Storm, and Inherit the Wind.

Published on February 15, 2014 07:21

February 13, 2014

Gun Control and Mental Health

I wish there were a way to screen out crazies--and can we call them crazies without bringing the wrath of Khan down?--from having guns. But there isn't. Until you do something tragic and terrible and final you get to buy whatever you want. In a democracy it's hard to do otherwise. The NRA says guns don't kill people, people kill people and I would extend that to "crazy" people kill people. Every notable shooting, it was obvious the killer was crazy. But how can you stop crazy people from buying guns? I mean, how would you even enforce that? Define crazy? Is a crazy somebody who's on Adderall? On Zoloft? On Prozac? Ritalin? Because you're taking it for something. Is a crazy someone who's seeing a shrink or, more likely, someone who avoids shrinks? And then what....we can't even get to a single payer health insurance system like the rest of the civilized world, are we going to agree to a central registry of crazy? And then, I think, even if you're certifiable, like that boy who killed the kids at Sandy Hook, even if he couldn't buy guns himself he could steal guns. No easy answer here.

Published on February 13, 2014 11:08

February 7, 2014

Paul Misencik's "The Original American Spies"

Here's my review of Paul Misencik's amazing new book, "The Original American Spies." It ran in the Stars and Stripes on Feb. 7, 2014.

In the last couple of years politicians have been talking a lot about our founding fathers and aligning themselves with their immutable purity of purpose and character. Of course, this causes red flags to go up because for one thing no one can know the motives or intents of people two hundred years dead no matter how many documents they’ve left behind. Anyone who’s been judged on a document or recording taken out of context knows how flabbergasting that is. Intent and purpose are nuanced things. Take away the moral, economic and social landscape and all that’s left is a faded two tone picture. And nothing lies like a photo. The other thing is this: What we learn in school about the early days of our country is distilled down to a belief in America’s inevitability and an exasperated disbelief that anyone would oppose our destiny. Basic American history books are a bloodless chronicle of good guys, bad guys and boisterous pronouncements. I always want to shake these history books to see if any humanity tumbles out.

With this background, I found it refreshing to read Paul R. Misencik’s new book, Original American Spies, Seven Covert Agents of the American Revolutionary War. Misencik uses lavish detail taken from extensive research to highlight the clandestine activities of seven Revolutionary War spies and puts them in the context of their times, their personal lives, and the larger war they operated in. The result is experiencing the Revolutionary War from the ground level and in real time.

It was a long war—1775-1783—and Misencik does a fine job of showing just what that meant: you had to declare your allegiance as either a Whig (American sympathizer) or a Tory (British sympathizer). Tory sympathies would get you much needed business, but it would earn you the wrath of the American mob or sabotage by rebel groups such as the Sons of Liberty. You needed passes to travel through occupied territory—and all territory was occupied by either the Americans or British—to get simple supplies like a bag of flour, and you had to live with the constant suspicions and paranoia that no one was who they said they were. Living in 2014, it’s hard to imagine not having the freedom to espouse your political beliefs, but that’s what it was like in 1775 when the war started.

There weren’t a lot of volunteers for spy duty and Washington had to appeal to patriotism rather than the romance of being a colonial James Bond. And being a spy in the Revolutionary War required specific talents that might seem quaint in the age of drones and cloud computing. For example, the spy had to be physically strong and had to have a good memory as anything written down would be used as evidence against him or her, and, as the unnegotiable punishment for spying was death by hanging, the spy had to possess a large dose of courage.

Misencik tells the story of Lydia Barrington Darragh, a female spy whose large house in Philadelphia was requisitioned by the British for meetings. She realized soon that, as a woman, she was invisible to the British and she could go in and out of these meetings unnoticed except for requests for refreshments. Darragh didn’t start out wanting to spy, but she seized her advantage and found ways to send all her intelligence to General Washington. Most noteworthy was the intelligence that British General Howe intended to surprise the Americans at Whitemarsh and because of Darragh’s stealth and fast action, Howe met a well prepared army and retreated.

Misencik makes the point repeatedly that spying was not an honorable occupation and after the war many spies chose to keep their wartime spying activity to themselves, even if it meant financial ruin. This was the case for James Rivington, a publisher who loudly ridiculed the American independence movement and its leaders in his newspapers during the war even while extracting military intelligence from British officers and feeding it to the Americans. After the war, he spent time in debtor’s prison, rather than expose his secret role supporting the Americans— and thus jeopardize other family members who were on British pensions.

To me, the most interesting theme of Original American Spies was that the Americans and the British lived intertwined lives. Lydia Barrington Darragh, for example, had easy access not just because of her sex, but because her second cousin was serving as an aide to General Howe and appearing with her cousin gave her unspoken approval as a trustworthy hostess. Another female spy, Ann Bates—who spied for the British—had a husband who was a low-ranking infantryman in the British Army but received papers to pass into General Washington’s camp which were signed by Benedict Arnold. There was a lot of fluidity in family and patriotic alliances which would be hard to untangle even after the war was over. Although I think enough time has passed so we can forgive the British.

Paul R. Misencik is the author of two books besides Original American Spies (all published by McFarland): George Washington and the Half-King Chief Tanacharison: An Alliance that Began the French and Indian War, and Washington’s Teenage Spy: Sally Townsend of Oyster Bay due out later this year. He is a former international airline captain and is presently the Chief of the Operational Factors Division of the U. S. National Transportation Safety Board. He is a member of the First Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line, living history foundation. He lives in Reston, Virginia.

In the last couple of years politicians have been talking a lot about our founding fathers and aligning themselves with their immutable purity of purpose and character. Of course, this causes red flags to go up because for one thing no one can know the motives or intents of people two hundred years dead no matter how many documents they’ve left behind. Anyone who’s been judged on a document or recording taken out of context knows how flabbergasting that is. Intent and purpose are nuanced things. Take away the moral, economic and social landscape and all that’s left is a faded two tone picture. And nothing lies like a photo. The other thing is this: What we learn in school about the early days of our country is distilled down to a belief in America’s inevitability and an exasperated disbelief that anyone would oppose our destiny. Basic American history books are a bloodless chronicle of good guys, bad guys and boisterous pronouncements. I always want to shake these history books to see if any humanity tumbles out.

With this background, I found it refreshing to read Paul R. Misencik’s new book, Original American Spies, Seven Covert Agents of the American Revolutionary War. Misencik uses lavish detail taken from extensive research to highlight the clandestine activities of seven Revolutionary War spies and puts them in the context of their times, their personal lives, and the larger war they operated in. The result is experiencing the Revolutionary War from the ground level and in real time.

It was a long war—1775-1783—and Misencik does a fine job of showing just what that meant: you had to declare your allegiance as either a Whig (American sympathizer) or a Tory (British sympathizer). Tory sympathies would get you much needed business, but it would earn you the wrath of the American mob or sabotage by rebel groups such as the Sons of Liberty. You needed passes to travel through occupied territory—and all territory was occupied by either the Americans or British—to get simple supplies like a bag of flour, and you had to live with the constant suspicions and paranoia that no one was who they said they were. Living in 2014, it’s hard to imagine not having the freedom to espouse your political beliefs, but that’s what it was like in 1775 when the war started.

There weren’t a lot of volunteers for spy duty and Washington had to appeal to patriotism rather than the romance of being a colonial James Bond. And being a spy in the Revolutionary War required specific talents that might seem quaint in the age of drones and cloud computing. For example, the spy had to be physically strong and had to have a good memory as anything written down would be used as evidence against him or her, and, as the unnegotiable punishment for spying was death by hanging, the spy had to possess a large dose of courage.

Misencik tells the story of Lydia Barrington Darragh, a female spy whose large house in Philadelphia was requisitioned by the British for meetings. She realized soon that, as a woman, she was invisible to the British and she could go in and out of these meetings unnoticed except for requests for refreshments. Darragh didn’t start out wanting to spy, but she seized her advantage and found ways to send all her intelligence to General Washington. Most noteworthy was the intelligence that British General Howe intended to surprise the Americans at Whitemarsh and because of Darragh’s stealth and fast action, Howe met a well prepared army and retreated.

Misencik makes the point repeatedly that spying was not an honorable occupation and after the war many spies chose to keep their wartime spying activity to themselves, even if it meant financial ruin. This was the case for James Rivington, a publisher who loudly ridiculed the American independence movement and its leaders in his newspapers during the war even while extracting military intelligence from British officers and feeding it to the Americans. After the war, he spent time in debtor’s prison, rather than expose his secret role supporting the Americans— and thus jeopardize other family members who were on British pensions.

To me, the most interesting theme of Original American Spies was that the Americans and the British lived intertwined lives. Lydia Barrington Darragh, for example, had easy access not just because of her sex, but because her second cousin was serving as an aide to General Howe and appearing with her cousin gave her unspoken approval as a trustworthy hostess. Another female spy, Ann Bates—who spied for the British—had a husband who was a low-ranking infantryman in the British Army but received papers to pass into General Washington’s camp which were signed by Benedict Arnold. There was a lot of fluidity in family and patriotic alliances which would be hard to untangle even after the war was over. Although I think enough time has passed so we can forgive the British.

Paul R. Misencik is the author of two books besides Original American Spies (all published by McFarland): George Washington and the Half-King Chief Tanacharison: An Alliance that Began the French and Indian War, and Washington’s Teenage Spy: Sally Townsend of Oyster Bay due out later this year. He is a former international airline captain and is presently the Chief of the Operational Factors Division of the U. S. National Transportation Safety Board. He is a member of the First Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line, living history foundation. He lives in Reston, Virginia.

Published on February 07, 2014 04:51