Stewart M. Green's Blog, page 4

October 25, 2020

1876 & 2005: Helen Hunt Jackson and I Name The Whale in Red Rock Canyon

Red Rock Canyon Open Space, a 1,474-acre open space parkland on the western edge of Colorado Springs, opened to the public in November 2005 after being acquired by the City in 2003. Before the park opened there was a detailed master plan process to determine recreational uses, one of which was rock climbing. Since climbing is a historic use of city parks like the Garden of the Gods, it was a given that climbing would be an acceptable use.

In July of 2005, a bunch of local climbers got together and began establishing routes on the unclimbed slabs and faces flanking Red Rock Canyon. It was a wonderful opportunity to build a recreational climbing area on previously private, closed cliffs next to a major city. I was one of the activists and the only climber, besides Ric Geiman who worked for the parks department, to attend all the master plan meetings to ensure that we could climb in the new park.

Since I was one of the main route developers and the first to open new lines on the slabby walls, I went ahead and named most of the cliffs. I named the Westbay Wall for Billy Westbay, my old friend and climbing partner from the 1970s who had passed away a few years earlier, and the Wiggins Wall for Earl Wiggins, another friend and climbing pal, while Brian Shelton named the Sayers Wall for Ryan Sayers who died in a double lightning strike in the Wind River Range in Wyoming.

Ric Geiman named the Ripple Wall, a rippled cliff that he established most of the routes on. Other cliffs I named Solar Slab for its big hit of morning sunshine, the Wailing Wall since it reminded me of its Jeruselum namesake, and the Coyote Wall for a wily trickster I saw at the cliff base the first time I was there.

I named the last cliff, a huge hunk of pink sandstone that stretches a third of a mile along the canyon’s west flank, The Whale. It seemed appropriate because from the canyon floor the 80- to 100-foot-high wall appears like a giant surfacing whale. Probably a finback or maybe an elusive "red" whale.

A couple weeks ago I was reading a travel book by Helen Hunt Jackson (1830-1885), the original grande dame of Colorado Springs writers, that was published in 1878 as Bits of Travel at Home, a sequel to her bestseller Bits of Travel, a book about travels around Europe.

I’m working on a new edition of the Colorado section of Bits of Travel at Home with commentary, historic images, and my photographs that will be published later this winter by Every Adventure Publishing in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the founding of Colorado Springs next year.

So, as I was poring over the original text and reading a chapter called A Study of Red Canyon, imagine my surprise when I found that Ms. Jackson also referred to that hulking sandstone cliff as a whale.

She details a trip in a carriage up the then-wild canyon, called Red Canyon at that time, on June 4, 1876, a mere two months before the Colorado Territory became a state. She writes about the team of horses and carriage plunging across the deep frothy Fountain Creek and then the wonderland of the Red Canyon, fields of wildflowers, a silent woodland of pine and oak, the trickling creek on the canyon floor, and the magnificent red sandstone cliffs that hem the sides of the canyon. She called Red Canyon “a sudden sanctuary of refuge.”

This is Helen Hunt Jackson’s evocative description of The Whale:

“Now the canyon narrows again. It is only a chasm. The ledges on each side present a front as of myriads of plate edges, so thin are the layers and so many. Again, they are rounded and smooth. One on the right looks like a gigantic red whale, hundreds of rods long. Opposite him are great surfaces of slanting rock, finely striated, as with engravers’ tools. You can see only a few rods ahead. The road is a gully. Roses begin to make the air sweet. In a thicket of them, the road turns sharply round a high rock, and you are again in a little grassy open, some hundred yards wide. The great red stone whale on the right has his backbone higher than ever, and dozens of loose boulders are riding him. On the left hand the rock wall is perpendicular, serrated at top, and with slanting pinnacles shooting out here and there. Tall pines, also, seventy and eighty feet high, rooted in rocks where apparently is no crumb of earth. At the base of this wall, a thick copse of oak bushes, whose young leaves are of as tender and vivid a green as the leaves of slender white birches in June in New England.”

Her description takes me back to that sunny June day in 1876.

I wish I was there too, riding beside Ms. Jackson in that carriage up the rough track through thickets of scrub oak and meadows sprinkled with penstemon and paintbrush, stopping to take off my waistcoat and to take a long drink from the tumbling clear creek, looking up at the wall of cliffs above and thinking, yes, that looks like a whale surfacing below the vast Rocky Mountains.

And then another thought would have crossed my mind, I wonder if some future version of myself will climb on that sunny slab? Nah...

The Whale lifts its sandstone bulk above Red Rock Canyon on the west side of Colorado Springs. Photograph © Stewart M. Green

In July of 2005, a bunch of local climbers got together and began establishing routes on the unclimbed slabs and faces flanking Red Rock Canyon. It was a wonderful opportunity to build a recreational climbing area on previously private, closed cliffs next to a major city. I was one of the activists and the only climber, besides Ric Geiman who worked for the parks department, to attend all the master plan meetings to ensure that we could climb in the new park.

Since I was one of the main route developers and the first to open new lines on the slabby walls, I went ahead and named most of the cliffs. I named the Westbay Wall for Billy Westbay, my old friend and climbing partner from the 1970s who had passed away a few years earlier, and the Wiggins Wall for Earl Wiggins, another friend and climbing pal, while Brian Shelton named the Sayers Wall for Ryan Sayers who died in a double lightning strike in the Wind River Range in Wyoming.

Ric Geiman named the Ripple Wall, a rippled cliff that he established most of the routes on. Other cliffs I named Solar Slab for its big hit of morning sunshine, the Wailing Wall since it reminded me of its Jeruselum namesake, and the Coyote Wall for a wily trickster I saw at the cliff base the first time I was there.

I named the last cliff, a huge hunk of pink sandstone that stretches a third of a mile along the canyon’s west flank, The Whale. It seemed appropriate because from the canyon floor the 80- to 100-foot-high wall appears like a giant surfacing whale. Probably a finback or maybe an elusive "red" whale.

A couple weeks ago I was reading a travel book by Helen Hunt Jackson (1830-1885), the original grande dame of Colorado Springs writers, that was published in 1878 as Bits of Travel at Home, a sequel to her bestseller Bits of Travel, a book about travels around Europe.

I’m working on a new edition of the Colorado section of Bits of Travel at Home with commentary, historic images, and my photographs that will be published later this winter by Every Adventure Publishing in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the founding of Colorado Springs next year.

So, as I was poring over the original text and reading a chapter called A Study of Red Canyon, imagine my surprise when I found that Ms. Jackson also referred to that hulking sandstone cliff as a whale.

She details a trip in a carriage up the then-wild canyon, called Red Canyon at that time, on June 4, 1876, a mere two months before the Colorado Territory became a state. She writes about the team of horses and carriage plunging across the deep frothy Fountain Creek and then the wonderland of the Red Canyon, fields of wildflowers, a silent woodland of pine and oak, the trickling creek on the canyon floor, and the magnificent red sandstone cliffs that hem the sides of the canyon. She called Red Canyon “a sudden sanctuary of refuge.”

This is Helen Hunt Jackson’s evocative description of The Whale:

“Now the canyon narrows again. It is only a chasm. The ledges on each side present a front as of myriads of plate edges, so thin are the layers and so many. Again, they are rounded and smooth. One on the right looks like a gigantic red whale, hundreds of rods long. Opposite him are great surfaces of slanting rock, finely striated, as with engravers’ tools. You can see only a few rods ahead. The road is a gully. Roses begin to make the air sweet. In a thicket of them, the road turns sharply round a high rock, and you are again in a little grassy open, some hundred yards wide. The great red stone whale on the right has his backbone higher than ever, and dozens of loose boulders are riding him. On the left hand the rock wall is perpendicular, serrated at top, and with slanting pinnacles shooting out here and there. Tall pines, also, seventy and eighty feet high, rooted in rocks where apparently is no crumb of earth. At the base of this wall, a thick copse of oak bushes, whose young leaves are of as tender and vivid a green as the leaves of slender white birches in June in New England.”

Her description takes me back to that sunny June day in 1876.

I wish I was there too, riding beside Ms. Jackson in that carriage up the rough track through thickets of scrub oak and meadows sprinkled with penstemon and paintbrush, stopping to take off my waistcoat and to take a long drink from the tumbling clear creek, looking up at the wall of cliffs above and thinking, yes, that looks like a whale surfacing below the vast Rocky Mountains.

And then another thought would have crossed my mind, I wonder if some future version of myself will climb on that sunny slab? Nah...

The Whale lifts its sandstone bulk above Red Rock Canyon on the west side of Colorado Springs. Photograph © Stewart M. Green

Published on October 25, 2020 12:25

October 24, 2020

Time Traveling to the World's Largest Dinosaur Trackway

Yesterday, my daughter Aubrey and I went way, way, way back through the wilderness of time, actually to 150,439,697 years ago when I was still a twinkle in my mama's eye, to Jurassic Park times.

Looking out the dim portal of my handy time-travel machine, a cramped and clunky contraption designed in the mind of HG Wells, we glimpsed giant sauropods plodding across a muddy beach along the edge of a shallow inland sea, now called Dinosaur Lake, that washed emerald tides against a forest of towering tropical conifers and huge ferns.

Look! Look at that pair of Apatosaurs on the right! Moving in tandem, the two gigantic beasts lifted graceful necks into the sunshine, warily looking left and right at smaller theropods, three-toed, bipedal monsters like Allosaurus that pranced across the sloppy beach in search of meaty prey.

Okay, so my imagination runs amok sometimes. But the truth of those observations is based on the ancient evidence left in a bed of sandstone straddling the edges of the Purgatoire River in southeastern Colorado.

The river twists across the broad bottomland of Picketwire Canyon, an arid place of stairstepped slopes topped with varnished sandstone cliffs, rattlesnakes and bull snakes coiled beneath shady boulders, the etched scribblings of vanished Americans on leaning rock walls, and, above the land, a blaze of omnipresent sunlight that desiccates living things.

On both banks of the meager river is what is now called the largest dinosaur trackway in the world, with over 1,900 fossilized footprints in over 130 separate trackways on gray limestone bedrock. Most of the trackways were made by massive dinosaurs, trampling the muddy beach or walking side by side in a westerly direction. This parallel movement indicates herd behavior. In contrast, the prints of the carnivorous therapods are randomly scattered around, indicating that these critters were possibly looking for someone to crunch.

While we can go to museums and see the skeletal remains of dinosaurs reconstructed on pedestals and much can be discovered about these long-extinct creatures that shared our planet, the Picketwire Canyon track site offers a look at the elusive behavior of the dinosaurs. It allows us to ponder with more certainty what made these animals tick and let's us wonder why were they walking west on that muddy beach.

This image on the south bank of the Purgatoire River shows Aubrey's shadow cast across a sauropod trackway and in the upper right corner are the trampled tracks of a dino herd. The right side of the tracks in this photograph are obscured by mud and debris from flash flooding last summer. Mud also fills the 18-inch-wide footprints in the obvious left-trending trackway.

Aubrey's shadow falls across dinosaur tracks at Picketwire Canyon dinosaur trackway, the largest trackway in the world with almost 2,000 individual dino tracks. Photo © Stewart M. Green

Looking out the dim portal of my handy time-travel machine, a cramped and clunky contraption designed in the mind of HG Wells, we glimpsed giant sauropods plodding across a muddy beach along the edge of a shallow inland sea, now called Dinosaur Lake, that washed emerald tides against a forest of towering tropical conifers and huge ferns.

Look! Look at that pair of Apatosaurs on the right! Moving in tandem, the two gigantic beasts lifted graceful necks into the sunshine, warily looking left and right at smaller theropods, three-toed, bipedal monsters like Allosaurus that pranced across the sloppy beach in search of meaty prey.

Okay, so my imagination runs amok sometimes. But the truth of those observations is based on the ancient evidence left in a bed of sandstone straddling the edges of the Purgatoire River in southeastern Colorado.

The river twists across the broad bottomland of Picketwire Canyon, an arid place of stairstepped slopes topped with varnished sandstone cliffs, rattlesnakes and bull snakes coiled beneath shady boulders, the etched scribblings of vanished Americans on leaning rock walls, and, above the land, a blaze of omnipresent sunlight that desiccates living things.

On both banks of the meager river is what is now called the largest dinosaur trackway in the world, with over 1,900 fossilized footprints in over 130 separate trackways on gray limestone bedrock. Most of the trackways were made by massive dinosaurs, trampling the muddy beach or walking side by side in a westerly direction. This parallel movement indicates herd behavior. In contrast, the prints of the carnivorous therapods are randomly scattered around, indicating that these critters were possibly looking for someone to crunch.

While we can go to museums and see the skeletal remains of dinosaurs reconstructed on pedestals and much can be discovered about these long-extinct creatures that shared our planet, the Picketwire Canyon track site offers a look at the elusive behavior of the dinosaurs. It allows us to ponder with more certainty what made these animals tick and let's us wonder why were they walking west on that muddy beach.

This image on the south bank of the Purgatoire River shows Aubrey's shadow cast across a sauropod trackway and in the upper right corner are the trampled tracks of a dino herd. The right side of the tracks in this photograph are obscured by mud and debris from flash flooding last summer. Mud also fills the 18-inch-wide footprints in the obvious left-trending trackway.

Aubrey's shadow falls across dinosaur tracks at Picketwire Canyon dinosaur trackway, the largest trackway in the world with almost 2,000 individual dino tracks. Photo © Stewart M. Green

Published on October 24, 2020 07:57

October 17, 2020

NEW BOOK! Best Hikes Albuquerque Now Available from Falcon Guides

I'm pleased to announce the release of my newest book

BEST HIKES ALBUQUERQUE

on October 12 2020 by FalconGuides!

I'm pleased to announce the release of my newest book

BEST HIKES ALBUQUERQUE

on October 12 2020 by FalconGuides!The book details 37 great hikes in central New Mexico, all within an hour's drive of Albuquerque. I've always loved exploring New Mexico and this book includes some of my favorite places in the Land of Enchantment.

These include Bandelier National Monument with its Ancestral Puebloan ruins and vast backcountry; Valles Caldera National Preserve in the Jemez Mountains; Kasha Katuwe-Tent Rocks National Monument, a wonderland of hoodoos, pinnacles, and creased cliffs on Cochiti Pueblo land; and, of course, the towering Sandia Mountains rising above Albuquerque and its remote trails and solitary rock climbing adventures.

Thank you to FalconGuides and their caring staff of editors and designers as well as the busy sales staff that keep all my books stocked on store shelves. All of you rock and I'm always proud to be an ambassador for my gold and black FalconGuides!!

Stay tuned in this space for a giveaway of a few copies of BEST HIKES ALBUQUERQUE that I will do in the next few weeks. The only catch is the winners will have to write a review of it on my Amazon page .

See you on the New Mexico trails that lead to sunny skies, ancient places, and forever views.

Published on October 17, 2020 09:21

April 9, 2020

NEW BOOK RELEASE: Best Climbs Moab 2nd Edition

I'm happy to announce that the new 2nd edition of my book BEST CLIMBS MOAB was released by FalconGuiides on April 1, 2020 and is available at websites and online retailers near your fingertips like Amazon and Barnes & Noble.Unfortunately, many of the fine bookstores and outdoor gear shops that carry BEST CLIMBS MOAB are closed during the pandemic, as is Moab and all of the great climbing areas near the town. If you're in Colorado Springs, call Mountain Chalet and they will bring a copy of the book out to you. Curbside service.So go ahead and order a copy of BEST CLIMBS MOAB from an online retailer and daydream about when we can touch fingers to sandstone and boot soles to tower summits! Just don't head out to the canyon country now so that the local medical services aren't overwhelmed.

Published on April 09, 2020 16:11

November 28, 2019

10 Reasons to be Thankful You're a Climber: Hallelujah! I'm a Climbing Bum!

Climbing is different from many other sports. The dangers of climbing make us acutely aware of our own life and mortality. Climbing helps you decide what is really important. Climbing transcends the mundane aspects of everyday life, of the ruts of job and money and houses and shopping that we fall into. It’s good to sit down with pen and paper, preferably on your favorite summit, and jot down why climbing is important to you and then be thankful for the climbs, friends, trips, adventures, and lessons that climbing has given you. Here are 10 reasons that make me thankful to be a climber and mountaineer. Travel, climb, and marvel at the beauty of the cliffs and monasteries at Meteora, one of Greece's most famous climbing areas. Photograph © Stewart M. Green1. You Travel to the Best Places on the PlanetAs a climber, you have the opportunity and the excuse to travel and be part of the wildest and most beautiful places on planet earth—granite walls at Yosemite Valley; the jagged Dolomite Mountains; Africa’s Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro; the canyonlands around Moab; the monastic cliffs at Meteora; and the rarified air of the Himalayan and Alaskan ranges. Enjoy the journey.

Travel, climb, and marvel at the beauty of the cliffs and monasteries at Meteora, one of Greece's most famous climbing areas. Photograph © Stewart M. Green1. You Travel to the Best Places on the PlanetAs a climber, you have the opportunity and the excuse to travel and be part of the wildest and most beautiful places on planet earth—granite walls at Yosemite Valley; the jagged Dolomite Mountains; Africa’s Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro; the canyonlands around Moab; the monastic cliffs at Meteora; and the rarified air of the Himalayan and Alaskan ranges. Enjoy the journey. Climb the Edge of Time like Ian Green at Jurassic Park for stunning views of Longs Peak and Rocky Mountain National Park. Photograph © Stewart M. Green2. You Find the Best ViewsClimbers, like eagles, have the best views, looking down from lofty mountain summits and desert towers onto the world below. You earn the views by climbing upward,front-pointing with crampons up a steep snow gully to a peak, or jamming cracks and face climbing up vertical rock walls to the cliff-top. At the summit, in the fading sunlight, you feel special and privy to a view few other people in the world will share.

Climb the Edge of Time like Ian Green at Jurassic Park for stunning views of Longs Peak and Rocky Mountain National Park. Photograph © Stewart M. Green2. You Find the Best ViewsClimbers, like eagles, have the best views, looking down from lofty mountain summits and desert towers onto the world below. You earn the views by climbing upward,front-pointing with crampons up a steep snow gully to a peak, or jamming cracks and face climbing up vertical rock walls to the cliff-top. At the summit, in the fading sunlight, you feel special and privy to a view few other people in the world will share. 3. You’re Part of a Worldwide CommunityClimbers live everywhere in the world and with social media sites like Facebook and Instagram you can connect with them and make new friends and climbing partners when you travel and climb around the world. If you’re traveling to Spain, Greece, Norway, Thailand, or Australia, you can hook up with locals who speak the same language of the rock and have a similar passion for vertical adventure. Friends for life.Visit Stanage Edge, Britain's most popular crag, on a summer weekend and you'll make lots of new friends. Photograph © Stewart M. Green

3. You’re Part of a Worldwide CommunityClimbers live everywhere in the world and with social media sites like Facebook and Instagram you can connect with them and make new friends and climbing partners when you travel and climb around the world. If you’re traveling to Spain, Greece, Norway, Thailand, or Australia, you can hook up with locals who speak the same language of the rock and have a similar passion for vertical adventure. Friends for life.Visit Stanage Edge, Britain's most popular crag, on a summer weekend and you'll make lots of new friends. Photograph © Stewart M. Green I hang out with climbing friends--Dr. Bill Springer and Brian Shelton--on the summit of Aires Butte at Zion National Park, Utah. Photograph © Stewart M. Green4. You are a Lifelong AdventurerClimbing is more than a sport—it’s a way of life. I started rock climbing when I was a 12-year-old kid in Colorado and never looked back. As a lifer, climbing shaped my life, my career, my relationships, and my friends. Even still my oldest friend is my longtime climbing partner Jimmie Dunn, who I first met and climbed with when I was a high school student in 1969.

I hang out with climbing friends--Dr. Bill Springer and Brian Shelton--on the summit of Aires Butte at Zion National Park, Utah. Photograph © Stewart M. Green4. You are a Lifelong AdventurerClimbing is more than a sport—it’s a way of life. I started rock climbing when I was a 12-year-old kid in Colorado and never looked back. As a lifer, climbing shaped my life, my career, my relationships, and my friends. Even still my oldest friend is my longtime climbing partner Jimmie Dunn, who I first met and climbed with when I was a high school student in 1969. You'll get strong like Noah Hannawalt when you climb hard at the Ute Pass Boulders. Photograph © Stewart M. Green 5. You’ve Got Strong HandsClimbing has two faces—the mental and the physical. To be a good climber requires a commitment to physical fitness, being conscious of your diet, and learning to be aware of your body’s rhythms. Unlike earthbound people, you learn to move across strange terrain using your hands, arms, legs, and feet in a vertical dance. You also develop strong hands…perfect for opening stubborn jars for your mom.

You'll get strong like Noah Hannawalt when you climb hard at the Ute Pass Boulders. Photograph © Stewart M. Green 5. You’ve Got Strong HandsClimbing has two faces—the mental and the physical. To be a good climber requires a commitment to physical fitness, being conscious of your diet, and learning to be aware of your body’s rhythms. Unlike earthbound people, you learn to move across strange terrain using your hands, arms, legs, and feet in a vertical dance. You also develop strong hands…perfect for opening stubborn jars for your mom.  As a climber, you spend lots of time outside hanging out with your climbing partners, like Dennis Jackson holding my son Ian on the left and Major Tom Luman on the right at the Black Canyon in 1979, at cliffs and campsites. Photograph © Stewart M. Green6. You Spend Quality Time OutsideAs a climber you spend a lot of time outside, away from the office, from home, from the indoor climbing gym. You learn about weather, dressing for bad conditions, and avoiding lightning strikes. You learn about routefinding and reading a map and compass or a GPS receiver unit so you can never get lost. You bivouac on big walls at Zion National Park and sleep nestled in a tent perched on the rocky flank of the Grand Teton. And when you return to civilization and normal life, nothing is the same. Your senses are heightened. Your world has expanded beyond the door stoop.

As a climber, you spend lots of time outside hanging out with your climbing partners, like Dennis Jackson holding my son Ian on the left and Major Tom Luman on the right at the Black Canyon in 1979, at cliffs and campsites. Photograph © Stewart M. Green6. You Spend Quality Time OutsideAs a climber you spend a lot of time outside, away from the office, from home, from the indoor climbing gym. You learn about weather, dressing for bad conditions, and avoiding lightning strikes. You learn about routefinding and reading a map and compass or a GPS receiver unit so you can never get lost. You bivouac on big walls at Zion National Park and sleep nestled in a tent perched on the rocky flank of the Grand Teton. And when you return to civilization and normal life, nothing is the same. Your senses are heightened. Your world has expanded beyond the door stoop. Climb to the top! Ian Green atop the Grinning Tooth on Pikes Peak. Photograph © Stewart M. Green7. You Climb to Live More FullyLife is a grand adventure and climbing lets you live life to the fullest extent. You have choices. You can choose to work five days a week in an office, to commute to work on a four-lane interstate, and to strive for that big house in the suburbs. Or you can see beyond work and career and pursue your passion for the mountains and the canyons and the cliffs. You can choose to live your life on different terms than “normal” people, finding joy, passion, and meaning in the great outdoors and, through your climbing adventures and the life lessons that climbing can teach, you can create and shape significant relationships with spouses, partners, children, family, and friends. Just don’t be a narcissist.

Climb to the top! Ian Green atop the Grinning Tooth on Pikes Peak. Photograph © Stewart M. Green7. You Climb to Live More FullyLife is a grand adventure and climbing lets you live life to the fullest extent. You have choices. You can choose to work five days a week in an office, to commute to work on a four-lane interstate, and to strive for that big house in the suburbs. Or you can see beyond work and career and pursue your passion for the mountains and the canyons and the cliffs. You can choose to live your life on different terms than “normal” people, finding joy, passion, and meaning in the great outdoors and, through your climbing adventures and the life lessons that climbing can teach, you can create and shape significant relationships with spouses, partners, children, family, and friends. Just don’t be a narcissist.  Climbing is dangerous, especially when you're hanging on a fragile rope on a long free rappel in Arizona's Black Mountains.Photograph © Stewart M. Green8. Climbing Teaches You that Life is FragileClimbing is dangerous. When you climb, when you fall, when you have a climbing accident, you realize how close to the edge you can be as a climber and mountaineer. You learn that the thread of life is fragile and sometimes thin and that we need to pay attention. As you live and age, some of your climbing friends will die in accidents on the rocks and in the mountains. That is part of the package that you sign up for when you become a climber, but that knowledge is also freeing. You have the gift of becoming aware of what is truly important in your life and what is trivial.

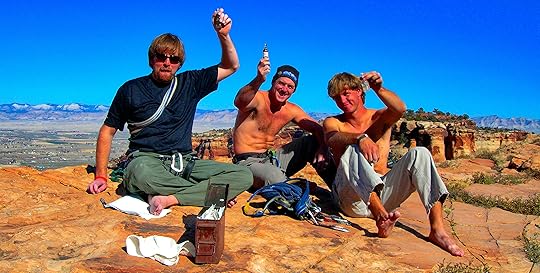

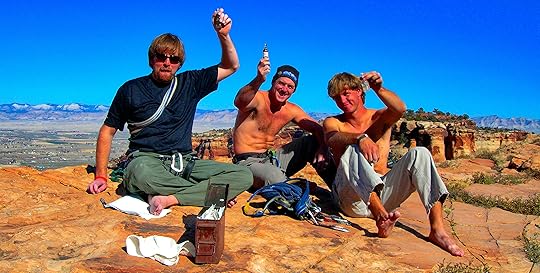

Climbing is dangerous, especially when you're hanging on a fragile rope on a long free rappel in Arizona's Black Mountains.Photograph © Stewart M. Green8. Climbing Teaches You that Life is FragileClimbing is dangerous. When you climb, when you fall, when you have a climbing accident, you realize how close to the edge you can be as a climber and mountaineer. You learn that the thread of life is fragile and sometimes thin and that we need to pay attention. As you live and age, some of your climbing friends will die in accidents on the rocks and in the mountains. That is part of the package that you sign up for when you become a climber, but that knowledge is also freeing. You have the gift of becoming aware of what is truly important in your life and what is trivial. Rob Masters, Brian Shelton, and CJ Sidebottom toast 1911 pioneering climber John Otto on the summit of Independence Monument at Colorado National Monument. Photograph © Stewart M. Green9. Climbing Gives You Great FriendshipsClimbing reflects the dichotomy of human experience. On one hand, I must climb alone, using my climbing skills and experience to reach the top. On the other hand, I am a member of a team. I have a partnership, a strong bond, with a climbing partner. Climbing is about partnership and friendship. As climbers, we work together and in doing so, we reach our summits and goals together. We look out for our climbing buddies, make sure they are safe, and they in turn do the same thing for us. They check our knots, give us belays, and encourage us to climb higher. As climbers we discover that life’s great adventures are to be shared together—we share life, joy, and adventure.

Rob Masters, Brian Shelton, and CJ Sidebottom toast 1911 pioneering climber John Otto on the summit of Independence Monument at Colorado National Monument. Photograph © Stewart M. Green9. Climbing Gives You Great FriendshipsClimbing reflects the dichotomy of human experience. On one hand, I must climb alone, using my climbing skills and experience to reach the top. On the other hand, I am a member of a team. I have a partnership, a strong bond, with a climbing partner. Climbing is about partnership and friendship. As climbers, we work together and in doing so, we reach our summits and goals together. We look out for our climbing buddies, make sure they are safe, and they in turn do the same thing for us. They check our knots, give us belays, and encourage us to climb higher. As climbers we discover that life’s great adventures are to be shared together—we share life, joy, and adventure. Climbing is a great adventure! Be grateful that you can stand on summits and climb vertical terrain that no one else dares to reach. Aubrey Green cranking at Penitente Canyon, Colorado. Photograph © Stewart M. Green10. You Learn that Life is ActionIt is good to be grateful for the many lessons that climbing mountains and cliffs gives us. One of the most important lessons is this: Climbing is action. It’s about doing, acting, trying, and being. It’s not about talking. Words don’t get you up a vertical rock face or to a remote mountain summit. Actions, the precise upward movement of hands and feet moving with delicate balance, gets you up. Climbing puts you in the moment. It takes you out of your head and thrusts you into the world with a primitive immediacy. Climb and find the great Eternal Now. Later, bring the lessons you learned from the vertical back to the tribe.

Climbing is a great adventure! Be grateful that you can stand on summits and climb vertical terrain that no one else dares to reach. Aubrey Green cranking at Penitente Canyon, Colorado. Photograph © Stewart M. Green10. You Learn that Life is ActionIt is good to be grateful for the many lessons that climbing mountains and cliffs gives us. One of the most important lessons is this: Climbing is action. It’s about doing, acting, trying, and being. It’s not about talking. Words don’t get you up a vertical rock face or to a remote mountain summit. Actions, the precise upward movement of hands and feet moving with delicate balance, gets you up. Climbing puts you in the moment. It takes you out of your head and thrusts you into the world with a primitive immediacy. Climb and find the great Eternal Now. Later, bring the lessons you learned from the vertical back to the tribe.

Travel, climb, and marvel at the beauty of the cliffs and monasteries at Meteora, one of Greece's most famous climbing areas. Photograph © Stewart M. Green1. You Travel to the Best Places on the PlanetAs a climber, you have the opportunity and the excuse to travel and be part of the wildest and most beautiful places on planet earth—granite walls at Yosemite Valley; the jagged Dolomite Mountains; Africa’s Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro; the canyonlands around Moab; the monastic cliffs at Meteora; and the rarified air of the Himalayan and Alaskan ranges. Enjoy the journey.

Travel, climb, and marvel at the beauty of the cliffs and monasteries at Meteora, one of Greece's most famous climbing areas. Photograph © Stewart M. Green1. You Travel to the Best Places on the PlanetAs a climber, you have the opportunity and the excuse to travel and be part of the wildest and most beautiful places on planet earth—granite walls at Yosemite Valley; the jagged Dolomite Mountains; Africa’s Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro; the canyonlands around Moab; the monastic cliffs at Meteora; and the rarified air of the Himalayan and Alaskan ranges. Enjoy the journey. Climb the Edge of Time like Ian Green at Jurassic Park for stunning views of Longs Peak and Rocky Mountain National Park. Photograph © Stewart M. Green2. You Find the Best ViewsClimbers, like eagles, have the best views, looking down from lofty mountain summits and desert towers onto the world below. You earn the views by climbing upward,front-pointing with crampons up a steep snow gully to a peak, or jamming cracks and face climbing up vertical rock walls to the cliff-top. At the summit, in the fading sunlight, you feel special and privy to a view few other people in the world will share.

Climb the Edge of Time like Ian Green at Jurassic Park for stunning views of Longs Peak and Rocky Mountain National Park. Photograph © Stewart M. Green2. You Find the Best ViewsClimbers, like eagles, have the best views, looking down from lofty mountain summits and desert towers onto the world below. You earn the views by climbing upward,front-pointing with crampons up a steep snow gully to a peak, or jamming cracks and face climbing up vertical rock walls to the cliff-top. At the summit, in the fading sunlight, you feel special and privy to a view few other people in the world will share. 3. You’re Part of a Worldwide CommunityClimbers live everywhere in the world and with social media sites like Facebook and Instagram you can connect with them and make new friends and climbing partners when you travel and climb around the world. If you’re traveling to Spain, Greece, Norway, Thailand, or Australia, you can hook up with locals who speak the same language of the rock and have a similar passion for vertical adventure. Friends for life.Visit Stanage Edge, Britain's most popular crag, on a summer weekend and you'll make lots of new friends. Photograph © Stewart M. Green

3. You’re Part of a Worldwide CommunityClimbers live everywhere in the world and with social media sites like Facebook and Instagram you can connect with them and make new friends and climbing partners when you travel and climb around the world. If you’re traveling to Spain, Greece, Norway, Thailand, or Australia, you can hook up with locals who speak the same language of the rock and have a similar passion for vertical adventure. Friends for life.Visit Stanage Edge, Britain's most popular crag, on a summer weekend and you'll make lots of new friends. Photograph © Stewart M. Green I hang out with climbing friends--Dr. Bill Springer and Brian Shelton--on the summit of Aires Butte at Zion National Park, Utah. Photograph © Stewart M. Green4. You are a Lifelong AdventurerClimbing is more than a sport—it’s a way of life. I started rock climbing when I was a 12-year-old kid in Colorado and never looked back. As a lifer, climbing shaped my life, my career, my relationships, and my friends. Even still my oldest friend is my longtime climbing partner Jimmie Dunn, who I first met and climbed with when I was a high school student in 1969.

I hang out with climbing friends--Dr. Bill Springer and Brian Shelton--on the summit of Aires Butte at Zion National Park, Utah. Photograph © Stewart M. Green4. You are a Lifelong AdventurerClimbing is more than a sport—it’s a way of life. I started rock climbing when I was a 12-year-old kid in Colorado and never looked back. As a lifer, climbing shaped my life, my career, my relationships, and my friends. Even still my oldest friend is my longtime climbing partner Jimmie Dunn, who I first met and climbed with when I was a high school student in 1969. You'll get strong like Noah Hannawalt when you climb hard at the Ute Pass Boulders. Photograph © Stewart M. Green 5. You’ve Got Strong HandsClimbing has two faces—the mental and the physical. To be a good climber requires a commitment to physical fitness, being conscious of your diet, and learning to be aware of your body’s rhythms. Unlike earthbound people, you learn to move across strange terrain using your hands, arms, legs, and feet in a vertical dance. You also develop strong hands…perfect for opening stubborn jars for your mom.

You'll get strong like Noah Hannawalt when you climb hard at the Ute Pass Boulders. Photograph © Stewart M. Green 5. You’ve Got Strong HandsClimbing has two faces—the mental and the physical. To be a good climber requires a commitment to physical fitness, being conscious of your diet, and learning to be aware of your body’s rhythms. Unlike earthbound people, you learn to move across strange terrain using your hands, arms, legs, and feet in a vertical dance. You also develop strong hands…perfect for opening stubborn jars for your mom.  As a climber, you spend lots of time outside hanging out with your climbing partners, like Dennis Jackson holding my son Ian on the left and Major Tom Luman on the right at the Black Canyon in 1979, at cliffs and campsites. Photograph © Stewart M. Green6. You Spend Quality Time OutsideAs a climber you spend a lot of time outside, away from the office, from home, from the indoor climbing gym. You learn about weather, dressing for bad conditions, and avoiding lightning strikes. You learn about routefinding and reading a map and compass or a GPS receiver unit so you can never get lost. You bivouac on big walls at Zion National Park and sleep nestled in a tent perched on the rocky flank of the Grand Teton. And when you return to civilization and normal life, nothing is the same. Your senses are heightened. Your world has expanded beyond the door stoop.

As a climber, you spend lots of time outside hanging out with your climbing partners, like Dennis Jackson holding my son Ian on the left and Major Tom Luman on the right at the Black Canyon in 1979, at cliffs and campsites. Photograph © Stewart M. Green6. You Spend Quality Time OutsideAs a climber you spend a lot of time outside, away from the office, from home, from the indoor climbing gym. You learn about weather, dressing for bad conditions, and avoiding lightning strikes. You learn about routefinding and reading a map and compass or a GPS receiver unit so you can never get lost. You bivouac on big walls at Zion National Park and sleep nestled in a tent perched on the rocky flank of the Grand Teton. And when you return to civilization and normal life, nothing is the same. Your senses are heightened. Your world has expanded beyond the door stoop. Climb to the top! Ian Green atop the Grinning Tooth on Pikes Peak. Photograph © Stewart M. Green7. You Climb to Live More FullyLife is a grand adventure and climbing lets you live life to the fullest extent. You have choices. You can choose to work five days a week in an office, to commute to work on a four-lane interstate, and to strive for that big house in the suburbs. Or you can see beyond work and career and pursue your passion for the mountains and the canyons and the cliffs. You can choose to live your life on different terms than “normal” people, finding joy, passion, and meaning in the great outdoors and, through your climbing adventures and the life lessons that climbing can teach, you can create and shape significant relationships with spouses, partners, children, family, and friends. Just don’t be a narcissist.

Climb to the top! Ian Green atop the Grinning Tooth on Pikes Peak. Photograph © Stewart M. Green7. You Climb to Live More FullyLife is a grand adventure and climbing lets you live life to the fullest extent. You have choices. You can choose to work five days a week in an office, to commute to work on a four-lane interstate, and to strive for that big house in the suburbs. Or you can see beyond work and career and pursue your passion for the mountains and the canyons and the cliffs. You can choose to live your life on different terms than “normal” people, finding joy, passion, and meaning in the great outdoors and, through your climbing adventures and the life lessons that climbing can teach, you can create and shape significant relationships with spouses, partners, children, family, and friends. Just don’t be a narcissist.  Climbing is dangerous, especially when you're hanging on a fragile rope on a long free rappel in Arizona's Black Mountains.Photograph © Stewart M. Green8. Climbing Teaches You that Life is FragileClimbing is dangerous. When you climb, when you fall, when you have a climbing accident, you realize how close to the edge you can be as a climber and mountaineer. You learn that the thread of life is fragile and sometimes thin and that we need to pay attention. As you live and age, some of your climbing friends will die in accidents on the rocks and in the mountains. That is part of the package that you sign up for when you become a climber, but that knowledge is also freeing. You have the gift of becoming aware of what is truly important in your life and what is trivial.

Climbing is dangerous, especially when you're hanging on a fragile rope on a long free rappel in Arizona's Black Mountains.Photograph © Stewart M. Green8. Climbing Teaches You that Life is FragileClimbing is dangerous. When you climb, when you fall, when you have a climbing accident, you realize how close to the edge you can be as a climber and mountaineer. You learn that the thread of life is fragile and sometimes thin and that we need to pay attention. As you live and age, some of your climbing friends will die in accidents on the rocks and in the mountains. That is part of the package that you sign up for when you become a climber, but that knowledge is also freeing. You have the gift of becoming aware of what is truly important in your life and what is trivial. Rob Masters, Brian Shelton, and CJ Sidebottom toast 1911 pioneering climber John Otto on the summit of Independence Monument at Colorado National Monument. Photograph © Stewart M. Green9. Climbing Gives You Great FriendshipsClimbing reflects the dichotomy of human experience. On one hand, I must climb alone, using my climbing skills and experience to reach the top. On the other hand, I am a member of a team. I have a partnership, a strong bond, with a climbing partner. Climbing is about partnership and friendship. As climbers, we work together and in doing so, we reach our summits and goals together. We look out for our climbing buddies, make sure they are safe, and they in turn do the same thing for us. They check our knots, give us belays, and encourage us to climb higher. As climbers we discover that life’s great adventures are to be shared together—we share life, joy, and adventure.

Rob Masters, Brian Shelton, and CJ Sidebottom toast 1911 pioneering climber John Otto on the summit of Independence Monument at Colorado National Monument. Photograph © Stewart M. Green9. Climbing Gives You Great FriendshipsClimbing reflects the dichotomy of human experience. On one hand, I must climb alone, using my climbing skills and experience to reach the top. On the other hand, I am a member of a team. I have a partnership, a strong bond, with a climbing partner. Climbing is about partnership and friendship. As climbers, we work together and in doing so, we reach our summits and goals together. We look out for our climbing buddies, make sure they are safe, and they in turn do the same thing for us. They check our knots, give us belays, and encourage us to climb higher. As climbers we discover that life’s great adventures are to be shared together—we share life, joy, and adventure. Climbing is a great adventure! Be grateful that you can stand on summits and climb vertical terrain that no one else dares to reach. Aubrey Green cranking at Penitente Canyon, Colorado. Photograph © Stewart M. Green10. You Learn that Life is ActionIt is good to be grateful for the many lessons that climbing mountains and cliffs gives us. One of the most important lessons is this: Climbing is action. It’s about doing, acting, trying, and being. It’s not about talking. Words don’t get you up a vertical rock face or to a remote mountain summit. Actions, the precise upward movement of hands and feet moving with delicate balance, gets you up. Climbing puts you in the moment. It takes you out of your head and thrusts you into the world with a primitive immediacy. Climb and find the great Eternal Now. Later, bring the lessons you learned from the vertical back to the tribe.

Climbing is a great adventure! Be grateful that you can stand on summits and climb vertical terrain that no one else dares to reach. Aubrey Green cranking at Penitente Canyon, Colorado. Photograph © Stewart M. Green10. You Learn that Life is ActionIt is good to be grateful for the many lessons that climbing mountains and cliffs gives us. One of the most important lessons is this: Climbing is action. It’s about doing, acting, trying, and being. It’s not about talking. Words don’t get you up a vertical rock face or to a remote mountain summit. Actions, the precise upward movement of hands and feet moving with delicate balance, gets you up. Climbing puts you in the moment. It takes you out of your head and thrusts you into the world with a primitive immediacy. Climb and find the great Eternal Now. Later, bring the lessons you learned from the vertical back to the tribe.

Published on November 28, 2019 21:33

October 12, 2019

NEW BOOK! Elevenmile Canyon Rock Climbing Guide Released by Every Adventure Publishing

I'm happy to announce the release of my newest book ELEVENMILE CANYON ROCK CLIMBING GUIDE by Every Adventure Publishing!The previous Elevenmile Canyon guidebook has been out of print since earlier this year, so the Mountain Chalet, our iconic outdoor sports and climbing shop in Colorado Springs, urged me to finish an Elevenmile guide that I had started 10 years ago. The result is this gorgeous guide to lots of the amazing cliffs and routes, including many new ones, in the canyon, one of my favorite places to climb and hang out.The book is available currently at Mountain Chalet and REI in Colorado Springs, Ouray Mountain Sports in Ouray, and from Amazon.ORDER NOW from Amazon and get a discounted price.Thanks also to Mollie Bailey, one of our great climbing guides at Front Range Climbing Company, for cranking some routes on Elevenmile Dome for the book cover.

I'm happy to announce the release of my newest book ELEVENMILE CANYON ROCK CLIMBING GUIDE by Every Adventure Publishing!The previous Elevenmile Canyon guidebook has been out of print since earlier this year, so the Mountain Chalet, our iconic outdoor sports and climbing shop in Colorado Springs, urged me to finish an Elevenmile guide that I had started 10 years ago. The result is this gorgeous guide to lots of the amazing cliffs and routes, including many new ones, in the canyon, one of my favorite places to climb and hang out.The book is available currently at Mountain Chalet and REI in Colorado Springs, Ouray Mountain Sports in Ouray, and from Amazon.ORDER NOW from Amazon and get a discounted price.Thanks also to Mollie Bailey, one of our great climbing guides at Front Range Climbing Company, for cranking some routes on Elevenmile Dome for the book cover.

Published on October 12, 2019 14:16

July 29, 2019

Dateline 1970: First Ascent of a Colorado Centennial Peak

I stand on the summit of 13,932-foot Thunder Pyramid in Colorado's Elk Range after the first ascent of the peak on August 2, 1970. I was 17 years old and had graduated from Palmer High School in Colorado Springs that June. Image was shot by Spencer Swanger with my Kodak Instamatic camera.The following is the story of a notable first ascent I did 49 years ago on August 2, 1970. Next year is the 50th anniversary of the first ascent. I plan to re-enact the ascent. Who’s going to join me?As climbers, we go out into the world to have fun, to have an adventure, to find new places, and to challenge ourselves. We usually don’t think about the meaning of what we do too often or place our adventures within a greater context. It’s only later, maybe years later, that the mountains and cliffs and towers that we’ve climbed begin to assume an historical context, to have meaning beyond our own lives.The Golden Age of ClimbingThat’s how it’s been for me. I began climbing in 1965 when I was 12 years old in North Cheyenne Cañon, a Colorado Springs city park filled with bristling granite pinnacles and cliffs, in what might seem now to be the dark ages of climbing since we used goldline ropes, carried racks of angle and blade pitons and a piton hammer, and either tied the rope around our waists or fashioned a Swiss-seat harness from one-inch webbing. That era was, of course, actually a golden age when there was still so much to climb and so many mountains and cliffs were unclimbed in the United States.Meet Spencer SwangerI first met Spencer Swanger in early 1968 when I was a skinny high school kid on a Colorado Mountain Club (CMC) trip on a winter trek up 14,264-foot-high Mount Lincoln. So, I adopted Spence, a Colorado Springs postal carrier, as my mountain mentor. He was 13 years older than me and was a real mountain man. He had already climbed all 54 Colorado Fourteeners by 1969. Swanger went on to become the first person to climb the hundred highest peaks in Colorado, a task he completed by soloing Red Mountain in the Culebra Range in 1977. My mom also liked me to climb with Spence since he was an older responsible guy with a family. She figured he was a good role model and probably not a risk taker.An Unclimbed Peak in the Elk RangeDuring the summer of 1969 on one of our climbing trips up the Maroon Bells near Aspen, we noticed, while descending South Maroon Peak, a good looking mountain on the opposite ridge to the east and south of Pyramid Peak. I looked at the topo map and saw the peak was simply labeled 13,932. No name. In those days there were no Colorado mountain lists except the Fourteeners. That’s what folks climbed. A list of the 100 highest peaks was put together in 1969 by Bill Graves and published in the CMC magazine but no one had climbed the hundred highest peaks in Colorado. Certainly Peak 13,932 wasn’t on anyone’s radar.Peak Put on the CMC ScheduleOver the next winter we talked about that rough peak south of Pyramid and actually put together a plan to climb it the next summer. Spence put it on the calendar as a CMC trip for the first weekend of August and, with confidence in me, listed me as the co-leader since I had a hand in its discovery. The trip was limited to only six climbers, including us since it appeared to have, like most of the Elk Range peaks, plenty of loose rock.Climbing Party of 6On Sunday, August 2, 1970, the year I was set free from high school, Spence, myself, and four other climbers —Carson Black, Gordon Blanz, Jack Harry, and Bill Graves from Fort Collins. Yep, the same Bill Graves who put together the first list of Colorado’s 100 highest in 1968, which included unclimbed Peak 13,932.Scramble up a White GullyEarly that morning, after a night of rain, the six of us set off from Maroon Lake. I carried a 150-foot red perlon rope, a handful of blade pitons, 8 carabiners, and a Stubai piton hammer. We hiked south on the trail from Crater Lake before cutting up grassy hillsides, skirting cliff bands, and balancing across boulders to the base of a steep couloir filled with jumbled rock, what is today called the White Gully. We scrambled up the loose gully, still the standard route up the peak, until near the top, where we exited right and finished with a scramble over loose cliff bands to the virgin summit.No Evidence of a Previous AscentOn top there was no evidence that anyone else had ever climbed the peak. No cairn, no register, nothing disturbed. It was the first ascent of a mountain that no one else had ever climbed, let alone probably even noticed. Yet Peak 13,932 was separated by a longer ridge than the Maroon Bells across the valley, and the saddle between Pyramid Peak and it was 70 feet lower than that between the Bells.From Roof of the RockiesWilliam Bueler later wrote in his classic Colorado mountain history book Roof of the Rockies: “It is most interesting that as late as 1970 there could be found a distinctive peak of nearly 14,000 feet which apparently had not been climbed.” It was pretty amazing.Only Living Climbers to do a First Ascent of a CentennialIt turns out that Peak 13,932 was the last of Colorado’s hundred highest ranked peaks to be climbed. All the other ones, now usually called the Centennials, were first climbed by miners, government surveyors, or early climbers like those in the San Juan Mountaineers in the 1930s. It also turns out that Carson Black and I probably are the only climbers alive that made the first ascent of a Colorado Centennial peak! I say “probably” because I can’t locate two of the other climbers and both Swanger and Graves have passed to the great beyond.Naming Thunder MountainAs we sat on the summit of Peak 13,932, we munched lunch and talked about what to name the new peak. When a rumble of thunder pealed across the mountains, Spence said, “We better get off here. Why don’t we call it Thunder Mountain?” We all agreed. Now the name has been changed to Thunder Pyramid to reflect its proximity to its higher neighbor.Next Ascent 4 Years LaterLooking at the old summit register the other night, I saw that Thunder Mountain didn’t see another ascent for 4 years, when Willy Oehrli, a mountain guide from Switzerland, climbed it. The next ascent was in August 1976 by a couple guys from Los Angeles who noted, “We f…ed up, we wanted to climb Pyramid instead!”A Special AscentNow Thunder Pyramid is regularly climbed by peakbaggers but for me, even after climbing hundreds of first ascents of rock routes and doing early ascents of desert towers around Moab, my first ascent in the summer of 1970 with Spencer Swanger, the Centennial Man, of Peak 13,932, Thunder Mountain, is a special memory. I feel lucky to have been part of Colorado mountain climbing history.

I stand on the summit of 13,932-foot Thunder Pyramid in Colorado's Elk Range after the first ascent of the peak on August 2, 1970. I was 17 years old and had graduated from Palmer High School in Colorado Springs that June. Image was shot by Spencer Swanger with my Kodak Instamatic camera.The following is the story of a notable first ascent I did 49 years ago on August 2, 1970. Next year is the 50th anniversary of the first ascent. I plan to re-enact the ascent. Who’s going to join me?As climbers, we go out into the world to have fun, to have an adventure, to find new places, and to challenge ourselves. We usually don’t think about the meaning of what we do too often or place our adventures within a greater context. It’s only later, maybe years later, that the mountains and cliffs and towers that we’ve climbed begin to assume an historical context, to have meaning beyond our own lives.The Golden Age of ClimbingThat’s how it’s been for me. I began climbing in 1965 when I was 12 years old in North Cheyenne Cañon, a Colorado Springs city park filled with bristling granite pinnacles and cliffs, in what might seem now to be the dark ages of climbing since we used goldline ropes, carried racks of angle and blade pitons and a piton hammer, and either tied the rope around our waists or fashioned a Swiss-seat harness from one-inch webbing. That era was, of course, actually a golden age when there was still so much to climb and so many mountains and cliffs were unclimbed in the United States.Meet Spencer SwangerI first met Spencer Swanger in early 1968 when I was a skinny high school kid on a Colorado Mountain Club (CMC) trip on a winter trek up 14,264-foot-high Mount Lincoln. So, I adopted Spence, a Colorado Springs postal carrier, as my mountain mentor. He was 13 years older than me and was a real mountain man. He had already climbed all 54 Colorado Fourteeners by 1969. Swanger went on to become the first person to climb the hundred highest peaks in Colorado, a task he completed by soloing Red Mountain in the Culebra Range in 1977. My mom also liked me to climb with Spence since he was an older responsible guy with a family. She figured he was a good role model and probably not a risk taker.An Unclimbed Peak in the Elk RangeDuring the summer of 1969 on one of our climbing trips up the Maroon Bells near Aspen, we noticed, while descending South Maroon Peak, a good looking mountain on the opposite ridge to the east and south of Pyramid Peak. I looked at the topo map and saw the peak was simply labeled 13,932. No name. In those days there were no Colorado mountain lists except the Fourteeners. That’s what folks climbed. A list of the 100 highest peaks was put together in 1969 by Bill Graves and published in the CMC magazine but no one had climbed the hundred highest peaks in Colorado. Certainly Peak 13,932 wasn’t on anyone’s radar.Peak Put on the CMC ScheduleOver the next winter we talked about that rough peak south of Pyramid and actually put together a plan to climb it the next summer. Spence put it on the calendar as a CMC trip for the first weekend of August and, with confidence in me, listed me as the co-leader since I had a hand in its discovery. The trip was limited to only six climbers, including us since it appeared to have, like most of the Elk Range peaks, plenty of loose rock.Climbing Party of 6On Sunday, August 2, 1970, the year I was set free from high school, Spence, myself, and four other climbers —Carson Black, Gordon Blanz, Jack Harry, and Bill Graves from Fort Collins. Yep, the same Bill Graves who put together the first list of Colorado’s 100 highest in 1968, which included unclimbed Peak 13,932.Scramble up a White GullyEarly that morning, after a night of rain, the six of us set off from Maroon Lake. I carried a 150-foot red perlon rope, a handful of blade pitons, 8 carabiners, and a Stubai piton hammer. We hiked south on the trail from Crater Lake before cutting up grassy hillsides, skirting cliff bands, and balancing across boulders to the base of a steep couloir filled with jumbled rock, what is today called the White Gully. We scrambled up the loose gully, still the standard route up the peak, until near the top, where we exited right and finished with a scramble over loose cliff bands to the virgin summit.No Evidence of a Previous AscentOn top there was no evidence that anyone else had ever climbed the peak. No cairn, no register, nothing disturbed. It was the first ascent of a mountain that no one else had ever climbed, let alone probably even noticed. Yet Peak 13,932 was separated by a longer ridge than the Maroon Bells across the valley, and the saddle between Pyramid Peak and it was 70 feet lower than that between the Bells.From Roof of the RockiesWilliam Bueler later wrote in his classic Colorado mountain history book Roof of the Rockies: “It is most interesting that as late as 1970 there could be found a distinctive peak of nearly 14,000 feet which apparently had not been climbed.” It was pretty amazing.Only Living Climbers to do a First Ascent of a CentennialIt turns out that Peak 13,932 was the last of Colorado’s hundred highest ranked peaks to be climbed. All the other ones, now usually called the Centennials, were first climbed by miners, government surveyors, or early climbers like those in the San Juan Mountaineers in the 1930s. It also turns out that Carson Black and I probably are the only climbers alive that made the first ascent of a Colorado Centennial peak! I say “probably” because I can’t locate two of the other climbers and both Swanger and Graves have passed to the great beyond.Naming Thunder MountainAs we sat on the summit of Peak 13,932, we munched lunch and talked about what to name the new peak. When a rumble of thunder pealed across the mountains, Spence said, “We better get off here. Why don’t we call it Thunder Mountain?” We all agreed. Now the name has been changed to Thunder Pyramid to reflect its proximity to its higher neighbor.Next Ascent 4 Years LaterLooking at the old summit register the other night, I saw that Thunder Mountain didn’t see another ascent for 4 years, when Willy Oehrli, a mountain guide from Switzerland, climbed it. The next ascent was in August 1976 by a couple guys from Los Angeles who noted, “We f…ed up, we wanted to climb Pyramid instead!”A Special AscentNow Thunder Pyramid is regularly climbed by peakbaggers but for me, even after climbing hundreds of first ascents of rock routes and doing early ascents of desert towers around Moab, my first ascent in the summer of 1970 with Spencer Swanger, the Centennial Man, of Peak 13,932, Thunder Mountain, is a special memory. I feel lucky to have been part of Colorado mountain climbing history.

Published on July 29, 2019 21:02

July 22, 2019

Angry Prairie Rattlesnake at Ute Valley Park

This was my morning wake-up call today at Ute Valley Park in Colorado Springs. I was doing a quick hike up Popes Bluffs, an unranked summit, the high point of the park, and one of my favorite local hikes.I was walking up the gullied trail when this bad boy, a three-foot prairie rattlesnake with coarse, rusty scales, was sprawled across the trail in the early sun, although it was already 80 degrees at 8 o'clock. He felt my footsteps and quickly coiled into an aggressive position. The buzz of the vibrating rattles filled the air, warning me to step back and give the snake space.Once you've heard that unmistakable sound of a rattlesnake, the dry, raspy shaking like seeds in a dried husk, you never forget it. The sound puts you on edge, at once both thrilling and frightening. It can raise the hair on your neck and cover your arms with gooseflesh, especially if you're thrashing through the underbrush in west Texas or southern Arizona.I've had plenty of close encounters with rattlesnakes. If you venture out much in the drylands, tramping down dry stony washes, scrambling over talus slopes, and threading through dense willow thickets along trickling creeks then you will eventually meet up with a buzzworm.I saw a six-foot western diamondback with a body almost as thick as my thigh in Texas that raised my hair and I've been struck at a few times. One prairie rattler just missed me along lower Beaver Creek. He was knee-high in a mountain mahogany bush to get off the hot ground when I surprised him on a rocky slope. I jumped as he struck and he missed. I've seen plenty of Crotalus species: timber rattlers in New York, Connecticut, and once, seven of them in one day on Old Rag Mountain in Virginia; green Mojave rattlers in western Arizona and the Mojave Desert; sidewinders in southern California; and I once caught a rare western Massasauga at the Royal Gorge.This fella is a prairie rattlesnake or Crotalus viridis, the most common rattler along Colorado's Front Range. This one was mature, with a length of about three feet, although I didn't want to grab him to measure. It's important not to kill rattlers or any other snake since they're a vital part of every desert ecosystem, and besides, we're usually intruders in their homeland.It reminds me of an old poem, "To a Rattlesnake," by Vaida Stewart Montgomery. The last stanza reads:And yet, Old Rattlesnake, I honor you; You are a partner of the pioneer; You claim your own, as you've a right to do -- This was your Eden -- I intruded here.

Published on July 22, 2019 20:12

July 9, 2019

Interview with Stewart Green on Colorado Public Radio

I visited Grand Junction in western Colorado for a few days in late June. On a Wednesday morning I met up with Ryan Warner, the host of the Colorado Public Radio (CPR) daily program COLORADO MATTERS, at Skyview Point on the northern edge of Grand Mesa on the Grand Mesa Scenic Byway.Ryan and I talked about the new 5th edition of my book SCENIC DRIVING COLORADO (published by Globe Pequot Press) and about other Colorado scenic routes and the amazing airplane views from the top of Grand Mesa, a huge 10,000-foot-high island in the sky.The next morning I met up with Ryan in the CPR studio on Main Street in downtown Grand Junction for a live interview about the book. It was loads of fun. I greatly appreciate Colorado Matters, producer Michelle P. Fulcher, and Ryan for inviting me on this stellar show about Colorado and an opportunity to talk about my new best-selling book.Here is a link to an article on the CPR website about me and my book as well as a link to listen to the story. Check it out and see you on the road!

Published on July 09, 2019 13:32

May 10, 2019

NEW Editions of Best Climbs Rocky Mountain National Park and Best Climbs Denver and Boulder

The new second editions of my books BEST CLIMBS ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK and BEST CLIMBS DENVER & BOULDER were released this month by FalconGuides!Both books are updated for accuracy with changes to access, parking, trails, and routes, as well as some new photographs and covers.I've climbed most of the routes in the books at one time or another and had lots of fun and adventures, including some wild lightning storms in the Park, doing the 5th ascent of D7 on the Diamond with Doug Snively in 1972, bivouacking atop the Third Buttress on Hallett Peak, meeting Layton Kor on a belay ledge on Anthill Direct, shooting pics of Jim Halloway on Flagstaff Mountain, and...well, it's a long list of fun times. It's a good thing I never grew up...

The new second editions of my books BEST CLIMBS ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK and BEST CLIMBS DENVER & BOULDER were released this month by FalconGuides!Both books are updated for accuracy with changes to access, parking, trails, and routes, as well as some new photographs and covers.I've climbed most of the routes in the books at one time or another and had lots of fun and adventures, including some wild lightning storms in the Park, doing the 5th ascent of D7 on the Diamond with Doug Snively in 1972, bivouacking atop the Third Buttress on Hallett Peak, meeting Layton Kor on a belay ledge on Anthill Direct, shooting pics of Jim Halloway on Flagstaff Mountain, and...well, it's a long list of fun times. It's a good thing I never grew up...

Published on May 10, 2019 20:24