Lorina Stephens's Blog, page 9

October 26, 2021

A Book Bundle

I’ve heard over the years from many of my readers regarding the high price of print books and of shipping.

I can’t do anything about the cost of an individual print book, because it is what it is. Neither can I do anything about the cost of shipping, because, well, it is what it is. But I have been thinking. And that resulted in what might be a good thought, something which may very well entice readers to purchase my fiction because not only will you get what I think is a wondrous variety of reading, but a good deal on my entire collection, and free shipping in the bargain.

If you were to purchase all six of my works of fiction, you’d spend $111.94, plus shipping. So, I’m offering you all six trade paperbacks at $100.00, and free shipping. Now how’s that for a deal?

How to get the bundle?That’s quite simple. You can either use the button I’ve appended below, or you can go to any of the pages for my fiction works and click on the PayPal button that says:

Fiction bundle. All six novels worth $111.94 for $100.00 and free shipping.

Supply chain shortages

Supply chain shortagesAnd with supply chain shortages looming for this festive season, buying local is even more important than ever before. Why not support local? Offer the people on your list something truly unique and memorable?

If it’s any of my paintings you’re interested in, they all are shipped with protective packaging so you’ll be sure to receive your purchase in good condition. If you’re interested in more than one, contact me and we can arrange a discounted deal.

Petawawa River

Petawawa River7″ x 10″

watercolour on Arches 140lb hot pressed

100.00 unframed

copyright Lorina Stephens

October 19, 2021

Review: The Book of Secrets, by M.G. Vassanji

The Book of Secrets by M.G. Vassanji

The Book of Secrets by M.G. Vassanji

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Vassanji’s novel, The Book of Secrets, which was the recipient of the first Giller Prize, is a complex saga revolving around a diary kept by an Assistant District Commissioner in the fictitious town of Kikono, situated near the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, set around the time of WWI.

The diary isn’t so much a book of secrets. Rather, it is the secrets which are kept by the people associated with the diary, and the tragedy their secrets foment.

The writing is spare, what might be termed lean, yet it is that spare quality which lends a sense of penury and pain to the narrative. This is not a story of happy endings. This is a story about madness and compulsion, about the very worst of human nature, and into that darkness Vassanji creates a twisting, sometimes confusing narrative which flows from person to person as the diary is handed off, sometimes part of an occult shrine, sometimes forgotten and later unearthed to the surprise and sorrow of the next generation.

There are conversations in the narrative which are never spoken (secrets), and there are prejudices held and never revealed (more secrets), and crimes committed and entombed in memory (yet even more secrets). Layers upon layers of misery.

Not for the faint of heart. Not an easy read. Not a lazy afternoon in the hammock kind of fiction. But it is worth your time and attention.

October 8, 2021

Review: The Children of Ash and Elm, by Neil Price

The Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings by Neil Price

The Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings by Neil Price

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I received notification of this remarkable book through a group of archeologists specializing in Scandinavian history, specifically Viking. Their praise of Neil Price’s work did not disappoint.

My interest in this history pertains to a current novel in progress of my own, and certainly I’ve come away with a head bursting with all the latest findings, research, and an understanding of the Viking Era.

Written in an easy-to-read style, without compromising the importance of the information, Price details the cause of the Viking diaspora, the extent of it, their extraordinary and often violent culture, trade routes, spheres of influence, and a great deal more. This is essential reading, in my opinion, for anyone who has an interest in Viking culture.

October 7, 2021

New purchasing feature

A colleague of mine shared a fascinating new capability for authors who have their books listed on their website. He says:

There’s now an easy way to link directly to participating Canadian indie bookstores, local to whomever is clicking the link, to look up and/or order your chosen book. The caveat is that it only looks up indies that are using Bookmanager software, but Bookmanager is widely used and also a Canadian indie so it’s a win-win to me.

Sounds like a win-win to me as well. So, I’ve revised all my book pages to include the widget, and hopefully you’ll have another avenue available when you go to purchase any of my books.

If you’re curious about Bookmanager’s Shop Local feature find out more about it here.

October 6, 2021

A Halloween teaser for you

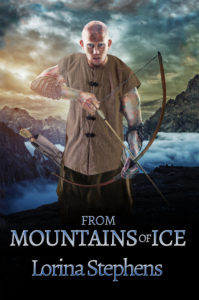

Probably the creepiest novel I’ve written is From Mountains of Ice.

Imagine you could speak with the dead, unwillingly, but able. Imagine their voices sometimes clamoured in your head, their memories, experiences, advice all there whenever you touched something made from their bones.

Then imagine your prince gone m

ad, your country drowning under taxation and a ruinous rule, and you the hope your people, dead and living, entreat to set things aright.

And so Sylvio diDanuto, banished, stripped of title and lands, himself now a bowyer who creates weapons from his ancestors’ bones, bows that can whisper in an archer’s mind, unwillingly accepts the burden of his country and embarks on a journey that will take him to places both physical and spiritual, and forever change who and what he is.

To tease you, to give you a taste, I’m offering up the first chapter of From Mountains of Ice in audiobook, deliciously narrated by Diana Majlinger. If you like what you hear, you can purchase the complete audiobook from Audible, Amazon and iTunes.

Or if you prefer print, or ebook, they are both available through this website, or from your favourite online bookseller. If purchasing print, give ABE Books a try — best prices and selection, and you’re supporting indie booksellers. Sometimes you can even acquire a used, signed copy. But I can also do that for you if you purchase directly from me.

In the meantime, enjoy this introduction to From Mountains of Ice. It’s a perfect pairing with any Halloween festivities.

01 - Chapter 1, part 1September 17, 2021

Blog Tour with Nathan Elberg

I am very pleased to host author Nathan Elberg today.

Nathan ElbergThe Cloth of Truth

Nathan ElbergThe Cloth of TruthBy Nathan Elberg

My father Yehuda Elberg was a Yiddish literary star, writing short stories, novels, lecturing in Argentina, Venezuela, the former Soviet Union and more. He was twice a Scholar-in-Residence at Oxford University. Nobel laureate Eli Wiesel declared my father was “the novelist of the Warsaw Ghetto,” whose book “Ship of the Hunted” was “…cut from the cloth of truth- of creative truth.”

My father was a member of the Jewish Underground during the Holocaust. He was captured three times by the Nazis, saw friends brutally murdered and lost most of his family. Yet he retained a keen sense of optimism, and a drive to rebuild both his family and his people after the war.

I’ve inherited some of my father’s ability to put words together into a story. I’ve also inherited some of his experiences as I listened to his descriptions, read his books and lectures. But thankfully, my life has been much less eventful than his. Most of the interesting things I’ve been involved in have been by choice, rather than the result of some life-or-death situation.

Although it was exciting, marching in protest on the Pentagon is not the same as Nazi storm troopers coming down your street wanting to kill you and all of your people. Isolating myself in an apartment with a big screen TV and high-speed internet is not the same as hiding inside a wall for a year, where making the wrong noise could cost your life and the life of your family.

But still, when I write fiction I want it to be “…cut from the cloth of truth- of creative truth.” I want it to be exciting. Perhaps I’m greedy, but I also want it to have social relevance, that it can get the reader to consider some relevant truth or issue. So, for example, as an anthropologist I knew about transgender shamanism. It’s nothing like the phenomenon in contemporary popular culture. It’s nothing like the ‘woke’ depiction I came across in a novel by one of my favorite authors (I stopped reading it). The transgender shaman in Quantum Cannibals is a complex, conflicted, frightening person, reflecting indigenous shamanism rather than contemporary western values (I introduce him in this blog post). My character is an explanation, rather than a lecture.

The novel The Red Badge of Courage is known for its realistic depictions of the Civil War, even though the author Stephen Crane was born after it ended. Hans Ruesch never met an Inuk (Eskimo) in his life, but his novel Top of The World is considered an accurate depiction of Inuit life and culture. These writers didn’t experience the lives or events they portrayed. They didn’t have access to Google. Nonetheless, their portrayals were accurate. Their stories were moving.

It’s possible to write fiction, even speculative fiction, that’s “…cut from the cloth of truth- of creative truth,” even if you didn’t personally participate in the event, aren’t from that culture, didn’t live in that era. (This is especially important for speculative fiction). What’s required though is a commitment to truth, where characters respond according to the dictates of a consistent time and culture, even when that culture is a product of your imagination.

Who is Nathan ElbergNathan Elberg has lived most of his life in Montreal, Canada. Following his graduation from McGill University, Honours degree in Anthropology, he conducted research on behalf of the Indians of Quebec Association, and several Departments of the Government of Canada. He obtained a Master’s Degree in Anthropology from the New School for Social Research, where he studied with Dr. Edmund Carpenter, one of the prime movers of the Toronto School of Communication Theory (along with Harold Innis and Marshal McLuhan). Elberg’s Supervisor was Prof. Michael Harner, who specialized in shamanic studies and cannibalism. Following graduation, Elberg worked as Research Director for the Labrador Inuit Association.

Elberg spent considerable time living with Cree Indians and Inuit. He passed a winter hunting, trapping and fishing deep in the boreal forest. He’s eaten everything from porcupine to walrus to beluga whale, which perhaps influenced him to eventually adopt a kosher diet.

As he raised a family he switched from anthropology to real estate, working as a commercial broker. He has three children, four grandchildren, and has been with his wife since nineteen seventy-four.

Elberg published his first short stories in Strobe Magazine while an undergraduate. His writing took a hiatus till 2002, following which several religious essays were published. His resumed writing fiction in 2010, when he began conceived the novel which eventually became Quantum Cannibals. publishing short stories both online and in print. Most are under his own name; some are under a nom-de-plum.

Elberg is Chairman of the International Board of Directors of a think tank, the Canadian Institute for Jewish Research, and has co-edited its publication on Aboriginal Zionism. He retired as a broker in 2018, and since then has devoted his energy to writing, research, and of course, social media.

Elberg’s novel Quantum Cannibals was first published in November 2018. A second edition came out in August 2020. It is genre-bending, character-driven literary speculative fiction that- like Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas or Huxley’s Eyeless in Gaza before it- weaves multiple intersecting narratives that span time, from Bronze Age Mesopotamia to a Post-Modern city-state. It’s the epic story of three incarnations of two people- alternately son and mother, husband and wife, father and daughter, savage and scholar, who simply want to return to the home they were brutally evicted from. Quantum Cannibals brings together authentic cultures and history from Melanesia, Siberia, Europe, the Americas, and more.

Elberg co-edited Zionism, An Indigenous Struggle, which was published jointly by the Canadian Institute for Jewish Research and RVP Press. It’s an anthology of articles examining the relationship between Native American and Jewish issues, focusing on Palestinian attempts to hijack the Native American struggle for rights and recognition into the framework of Palestinian suffering. Contributors include scholars, attorneys, Native Americans, Jews, and Jewish Native Americans.

www.nathanelberg.com www.quantumcannibals.com @QuantumCannibal

August 31, 2021

Another stop on the blog tour

Recently I hosted author Ira Nayman on my website. Today I appear on his at Les Pages Aux Folles.

I discuss my latest collection of short stories, Dreams of the Moon, and in particular the genesis of one of the stories: The Intersection.

Pop on over to Ira’s site to have a read, and while you’re there check out some of his other interesting offerings.

Dreams of the Moon is available worldwide in trade paperback and ebook from this site, and your favourite online bookstore, as well as elibrary systems.

August 30, 2021

Blog Tour with Nina Munteanu

…who is a remarkable individual, and someone I highly esteem even though we’ve never met face to face. I came to know Nina through SFCanada.

Nina Munteanu

Nina MunteanuNina Munteanu is a Canadian ecologist / limnologist and novelist. She is co-editor of Europa SF and currently teaches writing courses at George Brown College and the University of Toronto. The latest in her Alien Guidebook Series—The Ecology of Story: World as Character—is used in schools and universities worldwide. Visit www.ninamunteanu.ca for the latest on her books. Nina’s bilingual “La natura dell’acqua / The Way of Water” was published by Mincione Edizioni in Rome. Her non-fiction book “Water Is…” by Pixl Press(Vancouver) was selected by Margaret Atwood in the New York Times‘Year in Reading’ and was chosen as the 2017 Summer Read by Water Canada. Her novel “A Diary in the Age of Water” was released by Inanna Publications (Toronto) in June 2020. The novel was a finalist for the International Book Award 2021, silver medalist for the Literary Titan Award, Bronze winner of the Foreword Magazine’s ‘Book of the Year 2020’ and longlisted for Miramichi Review’s ‘Very Best Bok of the year award 2020’.

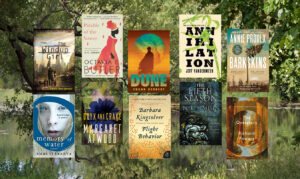

Ten Eco Fiction Novels Worth Reading and Discussingby Nina Munteanu

In most fiction, environment plays a passive role that lies embedded in stability and an unchanging status quo. From Adam Smith’s 18th Century economic vision to the conceit of bankers who drove the 2008 American housing bubble, humanity has consistently espoused the myth of a constant natural world capable of absorbing infinite abuse without oscillation. This thinking is the ideological manifestation of Holocene stability, remnants from 11,000 years of small variability in temperature and carbon dioxide levels. This stability easily gives rise to deep-seated habits and ideas about the resilience of the natural world.

But this is changing.

Our world is changing. We currently live in a world in which climate change poses a very real existential threat to most life currently on the planet. The new normal is change. And it is within this changing climate that eco-fiction is realizing itself as a literary pursuit worth engaging in.

Eco-Fiction (short for ecological fiction) is a kind of fiction in which the environment—or one aspect of the environment—plays a major role, either as premise or as character. Our part in environmental destruction is often embedded in eco-fiction themes, particularly if they are dystopian or cautionary (which they often are). At the heart of eco-fiction are strong relationships forged between a major character and an aspect of their environment. The environmental aspect may serve as a symbolic connection to theme and can illuminate through the sub-text of metaphor a core aspect of the main character and their journey: the grounding nature of the land of Tara for Scarlet O’Hara in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind; the over-exploited sacred white pine forests for the lost Mi’kmaq in Annie Proulx’s Barkskins; the mystical life-giving sandworms for the beleaguered Fremen of Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Many readers are seeking fiction that addresses environmental issues but explores a successful paradigm shift: fiction that accurately addresses our current issues with intelligence and hope. The power of envisioning a certain future is that the vision enables one to see it as possible.

“the best part about writing science fiction,” says Ottawa SF author Marie Bilodeau, “is showing different ways of being without having your characters struggle to gain rights. Invented worlds can host a social landscape where debated rights in this world – such as gay marriage, abortion and euthanasia – are just a fact of life.” The emerging sub-genre of ‘mundane science fiction’ addresses Bilodeau’s argument by featuring worlds and people within a new paradigm of ‘ordinary’. Eco-fiction examples of ‘mundane’ include Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Windup Girl and Kim Stanley Robinson’s post-climate-change drowned New York 2140. My novel A Diary in the Age of Water explores a near-future Toronto under severe water scarcity in which the national water utility oversees all aspects of environmental behaviour.

In fact, eco-fiction has been with us for decades—it just hasn’t been overtly recognized as a literary phenomenon until recently and particularly in light of mainstream concern with climate change (hence the recently adopted terms ‘climate fiction’, ‘cli-fi’, and ‘eco-punk’, all of which are eco-fiction). Strong environmental themes and/or eco-fiction characters populate all genres of fiction from the literary fiction of Richard Powers to the speculative fiction of Margaret Atwood and the science fiction of Frank Herbert. This establishes eco-fiction as a cross-genre phenomenon of literature better described as a focus or treatment than a sub-genre or brand, per se. My thought on the emergence of the term eco-fiction to describe works is that we are all awakening—novelists and readers of novels—to our changing environment. We are finally ready to see and portray environment as an interesting character with agency.

The ten examples I list below of impactful, highly enjoyable works of eco-fiction represent a range of genre, writing style, topic and treatment. Some are optimistic; others are not or have ambiguous endings that require interpretation. The relationship of humanity to environment also differs greatly among these examples as does the role of science. What they all have in common is that they are worth reading and discussing.

Flight Behavior by Barbara Kingsolver (HarperCollins, 2012) is a literary fiction, whose premise of climate change and its effect on the monarch butterfly migration is told through the eyes of Dellarobia Turnbow, a rural housewife, who yearns for meaning in her life. It starts with her scrambling up the forested mountain—slated to be clear cut—behind her eastern Tennessee farmhouse; she is desperate to take flight from her dull and pointless marriage of myopic routine. The first line of Kingsolver’s book reads: “A certain feeling comes from throwing your good life away, and it is one part rapture.” Dellarobia thinks she’s about to throw away her ordinary life by running away with the telephone man. But the rapture she’s about to experience is not from the thrill of truancy; it will come from the intervention of Nature when she witnesses the hill newly aflame with monarch butterflies who have changed their migration behavior.

Flight Behavior is a multi-layered metaphoric study of “flight” in all its iterations: as movement, flow, change, transition, beauty and transcendence. Flight Behavior isn’t so much about climate change and its effects and its continued denial as it is about our perceptions and the actions that rise from them: the motives that drive denial and belief. When Dellarobia questions Cub, her farmer husband, “Why would we believe Johnny Midgeon about something scientific, and not the scientists?” he responds, “Johnny Midgeon gives the weather report.” Kingsolver writes: “and Dellarobia saw her life pass before her eyes, contained in the small enclosure of this logic.”

The Overstory by Richard Powers (W.W. Norton, 2018) is a Pulitzer Prize winning work of literary fiction that follows the life-stories of nine characters and their journey with trees—and ultimately their shared conflict with corporate capitalist America.

Each character draws the archetype of a particular tree: there is Nicholas Hoel’s blighted chestnut that struggles to outlive its destiny; Mimi Ma’s bent mulberry, harbinger of things to come; Patricia Westerford’s marked up marcescent beech tree that sings a unique song; and Olivia Vandergriff’s ‘immortal’ ginko tree that cheats death—to name a few. Like all functional ecosystems, these disparate characters—and their trees—weave into each other’s journey toward a terrible irony. Each in his or her own way battles humanity’s canon of self-serving utility—from shape-shifting Acer saccharum to selfless sacrificing Tachigali versicolor—toward a kind of creative destruction.

At the heart of The Overstory is the pivotal life of botanist Patricia Westerford, who will inspire a movement. Westerford is a shy introvert who discovers that trees communicate, learn, trade goods and services—and have intelligence. When she shares her discovery, she is ridiculed by her peers and loses her position at the university. What follows is a fractal story of destiny, of trees with spirit, soul, and timeless societies—and their human avatars.

Maddaddam Trilogy by Margaret Atwood (McClelland & Stewart, 2013) is a work of speculative dystopian fiction that explores the premise of genetic experimentation and pharmaceutical engineering gone awry. On a larger scale the cautionary trilogy examines where the addiction to vanity, greed, and power may lead. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy explores a world where everything from sex to learning translates to power and ownership. Atwood begins the trilogy with Oryx and Crake in which Jimmy, aka Snowman (as in Abominable) lives a somnolent, disconsolate life in a post-apocalyptic world created by a viral pandemic that destroys human civilization. The two remaining books continue the saga with other survivors such as the religious sect God’s Gardeners in The Year of the Flood and the Crakers of Maddaddam.

The entire trilogy is a sharp-edged, dark contemplative essay that plays out like a warped tragedy written by a toked-up Shakespeare. Often sordid and disturbing, the trilogy follows the slow pace of introspection. The dark poetry of Atwood’s smart and edgy slice-of-life commentary is a poignant treatise on our dysfunctional society. Atwood accurately captures a growing zeitgeist that has lost the need for words like honor, integrity, compassion, humility, forgiveness, respect, and love in its vocabulary. And she has projected this trend into an alarmingly probable future. This is subversive eco-fiction at its best.

Dune by Frank Herbert (Penguin Random House, 1965) is a science fiction novel that chronicles the journey of young Paul Atreides, who according to the indigenous Fremen prophesy will eventually bring them freedom from their enslavement by the colonialists—The Harkonens—and allow them to live unfettered on the planet Arrakis, known as Dune. As the title of the book clearly reveals, this story is about place—a harsh desert planet whose 800 kph sandblasting winds could flay your flesh—and the power struggle between those who covet its arcane treasures and those who wish only to live free from slavery.

Dune is just as much about what it lacks (water) as it is about what it contains (desert and spice). The subtle connections of the desert planet with the drama of Dune is most apparent in the actions, language and thoughts of the Imperial ecologist-planetologist, Kynes—who rejects his Imperial duties to “go native.” He is the voice of the desert and, by extension, the voice of its native people, the Fremen. “The highest function of ecology is understanding consequences,” he later thinks to himself as he is dying in the desert, abandoned there without water or protection.

Place—and its powerful symbols of desert, water and spice—lies at the heart of this epic story about taking, giving and sharing. This is nowhere more apparent than in the fate of the immense sandworms, strong archetypes of Nature—large and graceful creatures whose movements in the vast desert sands resemble the elegant whales of our oceans.

Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer (HarperCollins, 2014) is a science fiction eco-thriller that explores humanity’s impulse to self-destruct within a natural world of living ‘alien’ profusion.

The first of the Southern Reach Trilogy, Annihilation follows four women scientists who journey across a strange barrier into Area X—a region that mysteriously appeared on a marshy coastline and associated with inexplicable anomalies and disappearances. The area was closed to the public for decades by a shadowy government that is studying it. Previous expeditions resulted in traumas, suicides or aggressive cancers of those who managed to return.

What follows is a bizarre exploration of how our own mutating mental states and self-destructive tendencies reflect a larger paradigm of creative-destruction—a hallmark of ecological succession, change, and overall resilience. VanderMeer masters the technique of weaving the bizarre intricacies of ecological relationship, into a meaningful tapestry of powerful interconnection. Bizarre but real biological mechanisms such as epigenetically-fluid DNA drive aspects of the story’s transcendent qualities of destruction and reconstruction.

The book reads like a psychological thriller. The main protagonist desperately seeks answers. When faced with a greater force or intent, she struggles against self-destruction to join and become something more. On one level Annihilation acts as parable to humanity’s cancerous destruction of what is ‘normal’ (through climate change and habitat destruction); on another, it explores how destruction and creation are two sides of a coin.

Barkskins by Annie Proulx (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2016) is a work of literary fiction that chronicles two wood cutters who arrive from the slums of Paris to Canada in 1693 and their descendants over 300 years of deforestation in North America.

The foreshadowing of doom for the magnificent forests is cast by the shadow of how settlers treat the Mi’kmaq people. The fate of the forests and the Mi’kmaq are inextricably linked through settler disrespect for anything indigenous and a fierce hunger for “more” of the forests and lands. Ensnared by settler greed, the Mi’kmaq lose their own culture; their links to the natural world erode with grave consequence.

Proulx weaves generational stories of two settler families into a crucible of terrible greed and tragic irony. The bleak impressions by the immigrants of a harsh environment crawling with pests underlies the combative mindset of the settlers who wish only to conquer and seize what they can of a presumed infinite resource. From the arrival of the Europeans in pristine forest to their destruction under the veil of global warming, Proulx lays out a saga of human-environment interaction and consequence that lingers with the aftertaste of a bitter wine.

Memory of Water by Emmi Itäranta (Harper Collins, 2014) is a work of speculative fiction about a post-climate change world of sea level rise. In this envisioned world, China rules Europe, which includes the Scandinavian Union, occupied by the power state of New Qian. Water is a powerful archetype, whose secret tea masters guard with their lives. One of them is 17-year old Noria Kaitio who is learning to become a tea master from her father. Tea masters alone know the location of hidden water sources, coveted by the new government.

Faced with moral choices that draw their conflict from the tension between love and self-preservation, young Noria must do or do not before the soldiers scrutinizing her make their move. The story unfolds incrementally through place. As with every stroke of an emerging watercolour painting, Itäranta layers in tension with each story-defining description. We sense the tension and unease viscerally, as we immerse ourselves in a dark place of oppression and intrigue. Itäranta’s lyrical narrative follows a deceptively quiet yet tense pace that builds like a slow tide into compelling crisis. Told in the literary fiction style of emotional nuances, Itäranta’s Memory of Water flows with mystery and suspense toward a poignant end.

The Broken Earth Trilogy by N.K. Jemison (Orbit, 2018) is a fantasy trilogy set in a far-future Earth devastated by periodic cataclysmic storms known as ‘seasons.’ These apocalyptic events last over generations, remaking the world and its inhabitants each time. Giant floating crystals called Obelisks suggest an advanced prior civilization.

In The Fifth Season, the first book of the trilogy, we are introduced to Essun, an Orogene—a person gifted with the ability to draw magical power from the Earth such as quelling earthquakes. Jemison used the term orogene from the geological term orogeny, which describes the process of mountain-building. Essun was taken from her home as a child and trained brutally at the facility called the Fulcrum. Jemison uses perspective and POV shifts to interweave Essun’s story with that of Damaya, just sent to the Fulcrum, and Syenite, who is about to leave on her first mission.

The second and third books, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky, carry through Jemison’s treatment of the dangers of marginalization, oppression, and misuse of power. Jemison’s cautionary dystopia explores the consequence of the inhumane profiteering of those who are marginalized and commodified.

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (Nightshade Books, 2009) is a work of mundane science fiction that occurs in 23rd century post-food crash Thailand after global warming has raised sea levels and carbon fuel sources are depleted. Thailand struggles under the tyrannical boot of predatory ag-biotech multinational giants that have fomented corruption and political strife through their plague-inducing genetic manipulations.

The book opens in Bangkok as ag-biotech farangs (foreigners) seek to exploit the secret Thai seedbank with its wealth of genetic material. Emiko is an illegal Japanese “windup” (genetically modified human), owned by a Thai sex club owner, and treated as a sub-human slave. Emiko embarks on a quest to escape her bonds and find her own people in the north. But like Bangkok—protected and trapped by the wall against a sea poised to claim it—Emiko cannot escape who and what she is: a gifted modified human, vilified and feared for the future she brings.

The rivalry between Thailand’s Minister of Trade and Minister of the Environment represents the central conflict of the novel, reflecting the current conflict of neo-liberal promotion of globalization and unaccountable exploitation with the forces of sustainability and environmental protection. Given the setting, both are extreme and there appears no middle ground for a balanced existence using responsible and sustainable means. Emiko, who represents that future, is precariously poised.

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler (Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993) is a science fiction dystopian novel set in 21st century America where civilization has collapsed due to climate change, wealth inequality and greed. Parable of the Sower is both a coming-of-age story and cautionary allegorical tale of race, gender and power. Told through journal entries, the novel follows the life of young Lauren Oya Olamina—cursed with hyperempathy—and her perilous journey to find and create a new home.

When her old home outside L.A. is destroyed and her family murdered, she joins an endless stream of refuges through the chaos of resource and water scarcity. Her survival skills are tested as she navigates a highly politicized battleground between various extremist groups and religious fanatics through a harsh environment of walled enclaves, pyro-addicts, thieves and murderers. What starts as a fight to survive inspires in Lauren a new vision of the world and gives birth to a new faith based on science: Earthseed. Written in 1993, this prescient novel and its sequel Parable of the Talent speak too clearly about the consequences of “making America Great Again.”

A version of this article first appeared on Tor.com in 2020.

August 27, 2021

Blog Tour with Ira Nayman

… is with fellow author, Ira Nayman.

Ira Nayman

Ira NaymanIra Nayman is a figment of the imagination of a lawn chair named Francois le Granfalloon. Francois has imagined a rich life for his character Ira featuring the publication of seven novels by Elsewhen Press, the most recent being called Bad Actors. Francois’ creation has been updating a web site of political and social satire, Les Pages aux Folles, for 19 years. In addition to this, imaginary Ira has a PhD in communications from McGill University and was a regular contributor to Creative Screenwriting magazine. Ira was also the editor of Amazing Stories magazine for two and a half years, but Francois is thinking that that may strain credibility, so he may remove it from his imaginings. All of his friends on the patio have urged Francois to write this down before he forgets it, but, being a lawn chair, he doesn’t have the hands to do it…

Taming the Troublesome Trilogy Childby Ira NaymanThe second novel in a trilogy is always a tricky thing to write. The first book can intrigue the reader with new characters and a new story. The final book can satisfy the reader by bringing the story to a meaningful conclusion. In the middle book, the main characters are not new (although introducing new characters is certainly a strategy) and, although it is possible to conclude subplots, the main plot cannot be resolved (otherwise, your trilogy wouldn’t need a third book).

Tis a dilemma.In The Multiverse Trilogy, I have attempted a workaround to the problem of the second novel. But first, a little context: at the end of the second novel in my Transdimensional Authority/Multiverse novel, You Can’t Kill the Multiverse (But You Can Mess With its Head), a madman sets off a device which he believes will destroy the multiverse. Nothing obvious happens. However, Doctor Alhambra, the main scientist of the Transdimensional Authority (the organization which monitors and polices travel between universes) sets up a monitoring system that would set off an alarm should any of the known universes in the multiverse begin to show signs of decay.

At the beginning of Good Intentions, the first book in the trilogy, the alarm goes off. A universe is going to collapse; the only question is when. Unfortunately, the universe contains billions of sentient beings. The diplomatic wing of the Transdimensional Authority hatches a desperate plan to help as many of the beings from that reality settle into other, stable universes as it can.

Good Intentions follows the adventures of the first alien refugee, Rodney Pendleton, as he adjusts to life on Earth Prime (and Earth Prime adjusts to life with Rodney Pendleton). Although there is occasional anti-alien immigrant grumbling and a fair bit of bureaucratic red tape, the first book in the trilogy is generally upbeat, with most human beings Rodney encounters trying their best to help him.

Bad Actors, the second book in the trilogy, takes place two years after the events of the first book, where tens of thousands of alien refugees have immigrated to Earth Prime. Unlike typical second books in a trilogy, Bad Actors does not continue a single story arc started in the first book. Instead, each of its six chapters contains a different storyline, only one of which involves Rodney Pendleton. My intention was for the structure of the novel to reflect the growing diversity of both the alien experience in the new universe and the human responses to the growing alien presence, some of which are quite nasty.

(FLASHFOWARD: In the final book of the trilogy, which has been submitted to my publisher and should be released in 2022, the narrative fractures further, foregoing chapters altogether for a stream of narrative fragments. It is now four years after the discovery of the dying universe, and a million aliens have been relocated to dozens of stable universes; the new narrative structure is meant to mimic the chaos of their experience. It has also occurred to me that the branching narrative over the three books reflects the branching nature of realities in a fractal multiverse. The ending of the trilogy should not come as a surprise to readers – it’s kind of baked into the premise – but I won’t reveal it for fear of being labelled a spoiler spoilsport. All I will say is that while this book continues to explore the darker aspects of the immigrant experience, it does end on a positive note.)

I have treated each book in the series as a stand-alone story, even though characters develop and (as seen by the connection between book two and the first book of the trilogy, which is the sixth book in the series) stories are sometimes connected. Because the trilogy doesn’t have a single story arc, a simple recap can bring the reader up to speed on the current state of the story, allowing the books to be read in any order. For example, The Ugly Truth starts with a Frequently Unasked Questions file that will hopefully set the scene for readers who have not read the previous books while amusing readers that have. (As a humour writer, one of my axioms is “exposition = death,” so I try my best to infuse necessary narrative explanations with comedy.)

(Hey – I may have been a little quick to close that parenthesis. Let me open the parentheses one more time to point out that although I am intellectualizing all over the place in this blog entry, the trilogy is, in fact, humorous. There is wordplay, safes falling from the sky, farts, absurd situations, cows falling from the sky, anvils falling from the sky, raucously witty dialogue, cultural references, breaking of the fourth wall, boulders falling from the sky and, of course, pies. Many, many pies. I wouldn’t want to give you the impression that the trilogy is a dry exercise in formalism.)

I think this fracturing narrative approach serves the Multiverse Refugees Trilogy well; in particular, by introducing new characters and situations, it helps me avoid the perennial problems of the middle child – sorry, I meant middle novel. Granted, it wouldn’t work for most trilogies, with their single story arc, but it would seem to be a fruitful approach for writers who are wiling to play with form.

August 26, 2021

Blog Tour with D.G. Valdron

I am very pleased to have been a guest author at Den Valdron’s website recently, where I talked about my latest collection of short stories, Dreams of the Moon, and in particular about the genesis of the second story in the collection, At Union, which first appeared in Postscripts to Darkness.

I’d also like you to:

Meet D.G. Valdron… who is a remarkable writer. I was very pleased to have published his first novel, The Mermaid’s Tale, which I still believe is one the most profound works of fantasy in the past 20 years. Alas, I did have to return all rights to authors last year when I had to do a restructuring of Five Rivers Publishing because of elder care.

D.G. Valdron

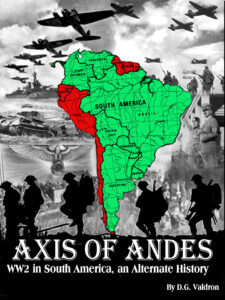

D.G. ValdronDen is a prodigious and prolific author. I’m pleased to feature him here where he talks about his latest work, an alternative history, Axis of Andes.

“Berlin, 1937, Adolph Hitler and his cabinet meet with a delegation from the tiny Latin American nation of Ecuador, seeking Germany’s help in deterring an invasion by their aggressive, larger neighbour Peru. The results of that fateful meeting set in motion a chain of events that will set the continent on fire, involving almost every country in South America a third theatre of World War II.” Axis of Andes, the Chronicle of the Andean wars.

Except that it never happened. But it might have. Welcome to Alternate History, emphasis on history.

You’ve probably heard of it, or at least seen it around. There are a lot of books and movies that start with the premise that the Confederacy wins the civil war, Harry Turtledove writes a lot of them. Or that explore Hitler winning World War II. We’ve all heard of The Man in the High Castle. Honestly, those subjects have been done to death.

But there’s more to Alternate History than that. History is not the careful linear progression we think it is, it is not a straight line pointing ever upwards. History is chaotic, anarchic, it’s full of left turns and unexpected developments. The past is littered with entire civilizations on their way to a glorious future when a car jumped the curb and they never saw it coming.

It could have gone the other way, something else could have happened, and everything would have been completely different.

Let me give you a tiny example. Gunpowder. There’s nothing inevitable about the components that make up gunpowder, there’s no reason to put them together at all. Gunpowder was an accident. It was created by a Chinese apothecary who was mixing different substances together to create a formula for immortality. Boy, did he get it wrong.

But it was a fluke. If that apothecary had settled on a different mixture, no gunpowder. No gunpowder, no fireworks, no explosives, no cannon, no rifles, no pistols. Without cannons, all those medieval European fortresses don’t become obsolete. Safe in their castles, Lords don’t have to bow to kings. European states don’t arise. Colonialism doesn’t happen. Machine guns aren’t invented, no world wars, we miss the bloody trench war of 1914. Everything changes.

Or, how about this – one tiny molecule shifts on a virus that lets it jump from bat to human. One guy infected with that virus who heels like hell, but instead of staying home and sleeping it off, he goes to the market and spreads it around… And here we are in the Coronaclypse.

Which brings me back to the Axis of Andes, and the chronicles of the Andean Wars. In our history, Latin America is a bit of a backwater. A collection of sleepy little countries, occasionally having petty wars and pettier dictatorships, a source of coffee and chocolate, but mostly, a place where nothing much happens that the rest of the world cares about. These are lands with vivid histories, full of tragedy and comedy, human aspiration and failure, so often overlooked.

Latin America was lucky to have largely avoided the horrors of both World Wars, and the transformations that came with them. But what if they hadn’t been lucky? What if one little thing, just one little thing had changed. And what if that one little change had rippled through, slowly gathering strength like a snowball rolling down the hill, setting other snowballs rolling, becoming an avalanche as it goes until everything is different and it’s all chaos and thunder.

What if Ecuador has a stable government that sees the war coming and does its best to put up a real fight. What if Ecuador, desperate to avoid an invasion tries to make alliances in Europe and Latin America, and these efforts change the politics of nations, leading to governments more bellicose or unstable, what if the relationships between these nations changes. The war that everyone struggles to avoid becomes inevitable, the dominos fall one by one, and everyone is drawn in..

Welcome to good people sensibly making bad decisions, and ordinary people muddling through as best they can. Welcome to tragedy as everyone sees their plans going hopelessly off the rails, and the absurdity that results.

Fair warning, this alternate history is a history. The Andean Wars aren’t a backdrop for some personal adventure. While there are narrative scenes of the characters as their lives play out, we take deep dives into the history of each nation, exploring their economies and societies, their schisms and their agendas. We see the real history of how each enters the depression, and see how each nation is transformed by accumulating events.

And within the framework of the Axis of the Andes, and the history of the Andean Wars, we explore the big questions, the nature of fascism, of racism, the triumphs of and ambitions, the paths that humans choose. In the end, it’s a breathtaking tale of folly as events proceed beyond everyone’s control.

I guarantee, you will have never read anything quite like it. If you want a slice of a world next door, a place where things turned out differently, check it out.

Axis of Andes and New World War, constitute two volume chronicle of the second world war as it might have come to South America. Available as an ebook on most platforms. And if you’re interested, check out my website and blog, for a journey into the quirky and strange, denvaldron.com.

Who is D.G. Valdron?First off, I’m very private, and quite reclusive. I don’t like having my picture up. I’m not thrilled with revealing much of anything about my life. But apparently, as a writer, you have to put yourself out there. So here goes.

I’m a wayward Maritimer (that’s the term for a person from the Atlantic Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia or Prince Edward Island), born on the north shore of New Brunswick, in a pulp and paper town called Dalhousie. Currently a denizen of the Canadian prairie.

My dad was a mechanic, my grandfather was a carpenter, and between the two of them, it left me an arsenal of skills, a work ethic, and a practical approach to life.

Dad worked two jobs actually. He was a papermaker at the mill, so was my grandfather, and so was my brother, so that was at least three generations of us. Dad had a tireless energy, on top of working at the mill, and being a mechanic with his own garage, we ran a car wash, a motel, a drive-in theatre, a lot of small businesses. Growing up, we did everything and worked on everything from retreading tires, to small manufacturing, to construction, to running cement, doing carpentry, and working on cars. We raised chickens. There was always something to do. We were all involved, the whole extended family.

The drive in was a big one though. I spent the summers of my youth working at a drive in theatre, which has left me with a lifelong appreciation for B-movies and pop culture. That and watching old carry-on movies, and older horror movies on Shock Theatre, late at nights when I was sleeping at the Garage, to keep it safe from break ins..

I was a little smarter than average, so that got me into University. It was a revelation, and I decided to spend the rest of my life there. I wanted to be a student forever, surrounded by books and ideas. I got into campus journalism, and began to experiment with being a writer, it was a heady time. I kept collecting degrees. But unfortunately that eventually wore thin so I decided to see what the rest of the world was like.

I’ve had the usual assortment of quirky writers jobs, mechanic, carpenter, projectionist, cook, waiter, woodcutter ditch-digger, journalist and school teacher. These days I’m a lawyer working in the field of aboriginal rights, I’ve been doing that for a while, I’m good at it, and I like to think I make a difference.

Let’s face it, anyone who wants a career in the arts needs to have a day job to pay the bills. And I’m trying to write a bit here and there.

I think I’ve been a writer my whole life, even when I wasn’t writing.