Kim Stanley Robinson's Blog, page 7

February 23, 2014

Stan the Californian

Boom - A Journal of California met Kim Stanley Robinson at his home and writing spot in Davis, California, for an extensive interview. His childhood, writing, science fiction, science, capitalism, utopia, his Three Californias trilogy, John Muir, and the history and landscape of California were addressed. Some excerpts:

Boom: Is there a special brand of California science fiction?

Robinson: I think so. It began with people like Jack London and Upton Sinclair, and then the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society in the 1940s. This included Ray Bradbury, who moved with his parents to Los Angeles when he was young, like I did, both of us from Waukegan, Illinois, but him maybe twenty years earlier. Bradbury was always focused on what modernization was doing to human beings, to the nontechnological aspects of humanity. There was also Robert Heinlein, who was living in Los Angeles in the forties. Crazy Bob they called him when he was young. He was always a strange amalgam. And then there was Philip K. Dick in northern California, also Poul Anderson and Jack Vance, Frank Herbert, and in her childhood, Ursula Le Guin. It turns out that many of the most interesting science fiction writers were in California. There’s something strange and powerful about California, as a landscape and an idea, so the place may have inspired the literature.

Boom: Your Three Californias trilogy lays out very different visions for California’s future. Which of the three Californias would you want to live in?

Robinson: Pacific Edge without a doubt. Pacific Edge was my first attempt to think about what would it be like if we reconfigured the landscape, the infrastructure, the social systems of California. I think eventually that’s where we’ll end up. It may be a five hundred year project. I thought of it as my utopian novel. But the famous problem of utopian novels as a genre is that they are cut off from history. They always somehow get a fresh start. I thought the interesting game to play would be to try to graft my utopia onto history and presume that we could trace the line from our current moment to the moment in the book. I don’t think I succeeded. I wish I had had the forethought to add about twenty pages of expository material on how they got to that society. Later I had a lot of dissatisfactions with Pacific Edge. You can’t have this gap in the history where the old man says, well, we did it, but never explains how. But every time I tried to think of the details it was like—well, Ernest Callenbach wrote Ecotopia, and then explained how they got to it in Ecotopia Emerging. And there’s not a single sentence in that prequel that you can believe. So, Pacific Edge was my attempt, a first attempt, and I think it’s still a nice vision of what Southern California could be. That coastal plain is so nice. From Santa Barbara to San Diego is the most gorgeous Mediterranean environment. And we’ve completely screwed it. To me now, it’s kind of a nightmare. When I go down there it creeps me out. I hope to spend more of my life in San Diego, which is one of my favorite places. But I’ll probably stick to west of the coast highway and stay on the beach as much as I can. I’ll deal, but we can do so much better.

Boom: In The Gold Coast, your dystopian novel in the California trilogy, and in your other dystopian novels, are you issuing a warning about where we’re headed?

Robinson: I am issuing a warning, yes. That’s one thing science fiction does. There are two sides of that coin, utopian and dystopian. The dystopian side is, if we continue, we will end up at this bad destination and we won’t like it. That’s worth doing sometimes. But I won’t do the apocalypse. That is not realist. It is more of a religious statement. I like disaster without apocalypse. Gold Coast is dystopian. And a lot of it has come true since it came out in 1988.

Boom: Do you think there is something special California can contribute to this utopian project?

Robinson: I do. I think we’re a working utopian project in progress, between the landscape and the fact that California has an international culture, with all our many languages. It’s got the UC system and the Cal State system, the whole master plan, all the colleges together, and Silicon Valley, and Hollywood. It’s some kind of miraculous conjunction. But conjunctions don’t last for long. And history may pass us by eventually, but for now it’s a miraculous conjunction of all of these forces. So I love California. Often when I go abroad and I’m asked where I’m from, I say California rather than America. California is an integral space that I admire. And we’re doing amazing things politically. I like the way the state is trending more left than the rest of America. And San Francisco is the great city of the world. I love San Francisco. I think of myself as living in its provinces—and provincials, of course, are often the ones who are proudest of the capital. And many of my San Francisco friends exhibit a civic pride that is intense, and I think justified. So there’s something going on here in California. I do think it’s somewhat accidental; so to an extent, it’s pride in an accident, or maybe you could say in a collective, in our particular history. So there’s no one thing or one person or group that can say, ah, we did it! It just kind of happened to us, in that several generations kept bashing away, and here we are. But when you have that feeling and it goes on, and continues to win elections and create environmental regulations, the clean air, the clean water, saving the Sierra, saving the coast: it’s all kind of beautiful. Maybe the state itself is doing it. Maybe this landscape itself is doing it.

Another utopia and climate change-focused article by Stan is up at IAI TV (a reprint from Australian magazine Arena).

The Australian Yahoo interviewed Stan on his most recent novel, Shaman, and the way he goes about writing. Some excerpts:

The final piece of Shaman fell into place when Robinson saw photos of 32,000-year-old cave paintings from France's Chauvet cave (discovered in 1995). "I was so struck by their beauty and age I felt I had my story, " he says. "I'd tell the story of the people who painted that cave." [...]

"I definitely enjoy my research, " he says. "It's reading with a purpose. I feel like I'm on the hunt, looking for good stories to tell, because I collect good stories from the research and retell them."

The process often begins years in advance as Robinson collects books and web links that seem relevant to an idea he's been "brooding on". When starting a book, he then looks for whatever he has on hand that's useful, but when he starts writing, the process changes to what he calls "iterative". "Once I've written a draft of a scene I know much better what I need to know to make it better, and that directs subsequent research."

Stan also wrote in NPR for three recommendations of New Wave SF: Thomas M. Disch's Camp Concentration; Joanna Russ's The Female Man; and Samuel R. Delany's Dhalgren.

And finally, you have one week left to submit a story to Stan! To The Best Of Our Knowledge, and partners University of Wisconsin’s Center for the Humanities and the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, are running a competition for a 500-600 hard-SF story that would be turned into a radio play, the deadline is March 1!

We’re looking for great sci-fi stories, based on real science and set in the near future. Sci-fi master Kim Stanley Robinson, best known for The Mars Trilogy, will choose the winner.

The winning stories will be turned into radio plays, produced by To the Best of Our Knowledge and LA’s Ensemble Studio Theatre, directed by Gates McFadden (Dr. Beverly Crusher on Star Trek: The Next Generation).

To your keyboards!

December 31, 2013

Shaman interviews & reviews III

Kim Stanley Robinson's latest novel SHAMAN, out since September 2013, is coming out in paperback on June 10 2014. Meanwhile, it has entered the Locus Bestseller list for December for hardcovers (at #7) -- while 2312 has been released in paperback and has made it to #1 and is continuing its run! (September, October, November, December)

Despite Shaman's setting in the long past, or rather quite the contrary, enriched by that fact, the New Yorker's Tim Krieder published an article on Stan: "Our Greatest Political Novelist?", which draws from both his Mars trilogy and Shaman to make a major point:

Depending on your own politics, this [the Martian Constitution] may sound like millennia-overdue common sense or a bong-fuelled 3 A.M.

wish list, but there’s no arguing that to implement it in the real

world circa 2013 would be, literally, revolutionary. My own bet would be

that either your grandchildren are going to be living by some of these

precepts, or else they won’t be living at all. [...] I don’t just

admire Robinson’s ambitions or agree with his agenda; I’m not

recommending his books because they’re good for you. Kim Stanley

Robinson is one of my favorite novelists, period. [...] The strength of his characterizations is inextricable from his power as a

political visionary; Robinson is realistic about human beings but

nonetheless optimistic about our capacity for change.

[...] Loon’s tribe in “Shaman” isn’t exactly a preagricultural

utopia—they’re starving by the end of each winter—but it’s still a

pretty benign view of man in his primeval state, closer to Rousseau than

Hobbes.

[...] Wouldn’t it ultimately be more optimistic to create a sort

of past-dystopia, showing us how far we’ve come? There’s evidence to

suggest that prehistoric cultures would’ve seemed far more savage and

alien to us than Robinson imagines here. I suspect this is less a

failure of imagination on his part than a triumph of his convictions

over the evidence, a projection of his resolute optimism backwards

through time to show us that folks are basically the same all over. [...] What he’s telling us over and over, like the voice of the Third Wind

whispering when all seems lost, is that it’s not too late, don’t get

scared, don’t give up, we’re almost there, we can do this, we just have

to keep going.

Let the debate begin!

Some more reviews for Shaman: Songs in Squee Minor ; The Sydney Morning Herald

and for 2312: Population GO

Stan participated again to Authors@Google last September, and read from Shaman and talked about creating the world of 30,000 years ago -- one of the great Shaman talks!

He also participated to a debate for iai tv on "Paradise...Lost?" with Marina Benjamin and Alex Callinicos:

Once a driving force of political change, utopian visions are now out

of fashion. But is this a lost opportunity or a new realism? Should

we create new utopias and thereby impel social advance, or will we

learn the lessons of history and remain sceptical of grand visions?

And so... happy new year 2014 AD!

November 10, 2013

Shaman interviews & reviews II

SHAMAN has been out for a few months now, in hardcover. Shaman is also out as an audiobook: Hachette, Ambling Books, ... It is read by Graeme Malcolm.

Stan was interviewed for Focus, an Illinois radio. Listen to him talk about his Mars trilogy and Shaman, and reminisce extensively about authors that inspire him, Ursula Le Guin and Gene Wolfe.

Stan participated in an online Q&A chat at Firedoglake Book Salon

-- a nice way to interact with the author directly. The questions and

answers are many and the whole chat long to go through, but extremely informative; Stan's answers

only can be read here. Some interesting bits below:

On science fiction writing and worldbuilding:

They are similar processes, in that they are both settings and

societies that don’t exist now, and so there has to be enough

information in the text for the reader to be able to envision them.

So this is a particular method of novel writing that includes

description as well as dramatized action, and it has to be fitted

into the story gracefully, if possible.

The paleolithic culture is one that really existed but which we

have to infer from very few remnants. A future society has not yet

existed, but presumably will still have elements of now that we know

well. So the absences that have to be filled in are different in

nature, but both require an effort of imagination on the part of both

writer and reader.

I’ve been interested in the paleolithic humans for a long time.

It’s part of my science fiction project; if you try to imagine what

humanity could become, you have to think about what we are now, and

how we became what we are–and that gets you back to the

paleolithic, where we evolved to what we are.

So I’m interested in sociobiology as a kind of sf science,

speculative about our deep primate nature and its effects on us now.

The fact that these people had the same genome we do is so very

suggestive; it means culture is very important, and also that we

might choose deliberately to live in ways that give us the best of

the paleolithic experience.

I think the last line of Loon’s wander is one of the great last

lines I have come up with, because we suddenly have to recalibrate

Loon’s age, and it should be a big surprise. But they had to grow

up fast.

On the setting of Shaman:

This all takes place near what is now Vallons

Pont d’Arc in the Ardeche region of France, near the Chauvet cave

and the stone arch over the river nearby.

Then also my characters trek up to the caribou steppes of northern

France, and also eventually get to the dry land of the English

strait, and the ice cap of the Ice Age itself, sitting on southern

England.

One way I think it’s more like 300 miles, but that trip is

unusual. I do posit a traveling and nomadic culture, but their usual

annual trek is more like 200 miles round trip; then there is an

emergency.

On research for Shaman:

I mostly read about these people but I

did try knapping stone and starting fires, and I spend a lot of time

backpacking where the activities are often similar. Snow camping is

also a technique. What I found interesting about the ice man was that

the design of his gear kit was so similar to mine in the mountains.

Different materials but same designs for same functions.

A lot of this story came to me as I wrote the book; more so than

usual with me. I knew the situation I wanted, and the relationships

at the beginning, the apprentice shaman and the old shaman and the

herb woman. I was thinking “first scientist” and “first artist”

and how culture was passed along so stably for thousands of years.

First is not the right word here, as by the time my people were

around the culture had been going for thousands of years. But you see

how I began. Then the story grew from there.

I wish the First Peoples in North America had a bigger presence in

the national consciousness. They have a particular wisdom to bring, a

long view, a relationship to the land, and to other people. I think

it’s real, although when you’re young it’s hard to sort out

feelings of this sort. It’s a bit overwhelming.

On Shaman and oral cultures:

When I fully grasped how huge a consciousness changer literacy is,

and how well their oral transmission had to be; and also what oral

transmission entails (which is not exactly word-by-word memorization,

but more patterns and stories and habits of mind, and proverbs) the

book completely changed, and the narrator, the third wind, began to

speak the book rather than write it. So I got a different narrator

with a different style, but also, the book had to be about that

process.

Even after all the work and thinking, I still think it is deeply

mysterious how people managed to do it–to keep a culture going for

hundreds of generations. It’s occurred to me that the lack of

literacy actually helped enable that, somehow. That writing would

have destabilized, as it still does. But it’s still mysterious.

As to the terms for sexual parts and acts, I had to think about

that for a long time and finally give up on English, because all the

words were too weighted with baggage of one kind or another. They all

sounded wrong, modern. All the language of the book had to be

examined, but there the modern weights and prejudices were so extreme

that I reverted to Basque, proto-IndoEuropean, and metaphors from

nature.

I tried to use only the words they would have, but thinking also

they had full language, with abstracts, but all coming from their own

situation.

So I didn’t use the word “fact” for instance, which I find

my narrators often used (“In fact,”….) Many like that. But

these people didn’t have facts as we understand that term.

It was a big exercise in linguistics and word definitions, also

cultures and philosophies and what they knew in their lives back

then.

Mama mia! I was so happy when a recent article stated that

historical linguists have determined that mama is one of the oldest

words in any language, a kind of sound happy babies make; and I/my

was really ancient too. I was just trying to suggest they would have

phrases from older languages around, other languages, and that it was

a Mother Earth religion where you would want an equivalent to OMG!!

but in the context of a Mother Earth religion. So it was a joke but I

meant it to work too. Actually it has thrown quite a few readers out

of the text, so maybe too much of a joke. But many of our old

commonplaces phrases are probably thousands of years old.

I think there may have been remnant

tales that lasted for thousand of years.

The swan wife story that Loon tells the shamans at the corroboree

is one of the oldest stories on Earth, found everywhere. I adapted

Loon’s from a Tlingit version and Gary Snyder’s version in his

Reed dissertation.

Also the story of the ten years without a summer that Thorn tells

early on, is my attempt to suggest that they were remembering the

disaster of 70,000 years ago, cause unknown, that reduced the human

population on Earth to perhaps 2,000 people, a thing we see by way of

the DNA bottleneck in the historical record of looking into our DNA

history! A new form of archeology, in effect.

And I was thinking, that Plato’s story of Atlantis and its

destruction was the story of Santorini blowing up in 1643 BC, about a

thousand years before Plato wrote it down, and perhaps an oral tale

all the time.

So I think some of these old stories (like the minotaur which I

also postulate in the book as ancient) are really old.

On writing and his ow novelistic style:

I’ve thought for some time now that

we love novels for different reasons, and one is to learn about how

it felt to live in different times and places; what people’s habits

were, what they did in daily life, and then what they thought and how

their feelings felt, but just in ordinary life.

Then we also want something more, which is when ordinary life

breaks down somehow and things go wrong or get strange or exciting;

and that’s plot. And we all love plot, and the hunger to turn pages

to know what comes next.

So, I think both are important. And in a prehistoric novel, I

thought it was important that daily life be fully established,

because for one thing, they didn’t have many of the plots we have

in modern life; the story was often the same, which was getting

enough food for winter, and doing all the basic paleolithc activities

of sustaining life and having families and so on. So, these are

events, but not plots. Then when plot comes, it could often be

catastrophic. Many plots are dealing with catastrophes to daily life

of one sort or another.

So, I have always done both, and have always disliked those novels

that are only plot. Thrillers, for instance; I don’t think they’re

that interesting.

So I am always testing the limits of readers’ patience here, I

guess, and many readers these days have almost no patience for that

kind of thing I do, especially in my own genre, science fiction.

So it’s a tension I deal with, and I can see that I have

especially fervent fans, and especially dismissive people who are not

fans.

I keep reminding myself that Proust’s novel is one of the

greatest of all, to encourage myself. And keep on trying to keep a

balance.

On what's next:

My next novel is going to be about a multi-generational starship,

actually.

But I don’t think they are going to work. I’m still working on

that idea.

It’s part of the thinking going on in 2312 and Shaman, and so I

think the three books will make a kind of argument for what we are

and what we can or should try to become in the future.

This is something my editor, Tim Holman, has been pointing out to

me; that these three books will make a kind of extended argument or

case.

He’s a great editor, I am so lucky to have him!

And he got me to say something I hadn’t realized, which is in

the little video clip of me on the internet, talking about Shaman;

that we now are living in a combination of the two books, that in a

sense we are already living 2312, whereas we are always living in

Shaman’s world too; that’s why now feels so weird and

disorienting. A nice thought!

Of course, reviews abound.

"Some" reviews below (beware of heavy spoilers in several!):

Kirkus ReviewsPublisher's Weekly

Geek Speak Magazine, Geonn Cannon

Chicks Dig Books, Jen C.

Colorado Springs Independent, Kel Munger

The Stardust Reader, Isabel

Fantasy Fiction, Spencer Wightman

Nerds of a Feather, Flock Together, The G

The Tattooed Book, Cara Fielder

SF Signal, John DeNardo

The Financial Times, James Lovegrove

Chicago Tribune, Gary K. Wolfe

Shelf Awareness, Lee E. Cart

SFcrowsnest, Kelly Jensen

Odd Engine, Peter Snede

Helen Lowe...on anything, really, Andrew Robins

Paranormal Haven, Beth

The Guardian, Josh Lacey

The Lost Entwife, Lydia

Cal Maritime Library, Mark Stackpole

Upcoming4me

io9, Michael Ann Dobbs

Mail & Guardian, Gwen Ansell

Historical Novel Society

And of course the pages for Shaman with user reviews in GoodReads, LibraryThing, Amazon.

November 6, 2013

Shaman interviews & reviews

Kim Stanley Robinsons' SHAMAN has now been out for a bit over two months. As the winter approaches, you might consider taking a step outside of your current life as an urban-dweller, with food available any time of the day any day, with buildings heated or cooled at will, and delve into our ancestor's minds -- a world challenging and stimulating, in an environment that actually still exists "out there" if you bother to seek it out. If you're not convinced yet, here are some recent interviews with the writer and some reviews on his work and most recent novel.

Above: Drawing of the Chauvet cave paintings by Eric Le Brun.

In an interview for the Library Journal, Stan explained many details in the thinking that went in writing Shaman.

More important for this book were certain other adventures in the

Sierra, especially winter trips on snowshoes, in steep terrain,

sometimes in storms, once or twice injured. These were crucial

experiences for when I wrote about my characters’ escape from the

northers.

In this novel, I looked to Anglo-Saxon for the feel of old words; to

proto-Indo-European, a lost language recovered by historical

linguistics; and to Basque, a very ancient language. Sometimes I used

these older words to replace sexual terms in our language that have too

much modern baggage.

And for those who were bothered by the fact that no map accompanied the book (but keep in mind that Loon's pack had no print maps or writing to begin with!), here is some context:

Yes, the story takes place mostly in the area around the Chauvet Cave,

near Vallon Pont d’Arc. The stone bridge that crosses the Ardèche River

there overlooks the home camp of my characters. During their seasonal

trek to the caribou steppes, they walk to north of the Massif Centrale,

and then some of them continue as far north as the southern edge of the

Ice Age’s great ice cap, in Cornwall. They can walk there because there

was no English Channel at that time, sea level being so much lower.

In this interview for Amazing Stories, Stan goes through his entire career, from his early Three Californias to Shaman:

I think of my novel Shaman as

a particular kind of science fiction, which examines what we are as

human beings by looking at how we became what we are now. Also, it took

the sciences of archeology and anthropology to provide the information

necessary to write the book, because prehistory is literally

prehistorical, in that we have no texts from the time, and have to infer

what life was like by what was left behind, and by analogy to first

peoples still around when industrial society colonized the planet. So,

this is partly a scientific process, and I have made use of all those

findings, some of them very new, to write my book.

In particular, the 1991 finding of the ice man on the glacier between

Italy and Austria, with all his gear frozen and intact, was a big

inspiration to me; his gear kit was very sophisticated and resembled my

backpacking gear in design, and I wanted to write about that. Then the

discovery of the Chauvet cave in 1994 gave me my particular story; it

was painted 32,000 years ago, the paintings are beautiful, and they

suggest an animal-focused culture with mysterious beliefs. So I tried

to tell the story of the people who painted the cave.

[...] Dystopias are all basically the same, and easy: oppression,

resistance, conflict, blah blah. Like car crashes in thriller movies.

But utopian novels are interesting (I know this is backwards to the

common wisdom) because they force us to think about what we are, what we

could become, and if we were to make a decent civilization, what would

endanger it, or keep it from spreading, etc. One point I’ve been making

all along is that even in a utopian situation, there will still be

death and lost love, so there will be no shortage of tragedy in utopia.

It will just be the necessary or unavoidable tragedies; which perhaps

makes them even worse, or more tragic. They won’t be just brutal

stupidities, in other words, but reality itself. This is what

literature should explore.

Also, thinking of utopia, I’ve always felt this: since we could do

it, we should. And that will take some planning, some vision.

[...] sf looks at the present and imagines the various futures that could come

to pass, given where we are now. It’s not prediction of one future,

but consideration of a multitude of possible futures, and that gives sf

readers their particular flexibility of mind, their ability to react to

history without huge surprise and disorientation. In effect, they saw

it coming. So sf reading is a kind of cognitive mapping that orients

people in time. It’s not just great fun, but useful too.

Please give us a glimpse of your writing process from conception to award-winning novel.

It usually

starts with an idea, fairly simple and basic. Inhabit Mars and

terraform it. What would the world be like if all the Europeans had

died in the Black Death? What if Galileo were taken by time travelers

to the moons of Jupiter? What if a mercurial personality and a

saturnine personality fell in love?

Then I build from there. Often it takes many years, and eventually I

have a sense of the story’s basic outline, with some events, and the

climax or ending, but a lot of vagueness. Eventually I need to figure

out a form, and then a narrator. The story tends to create the

characters necessary to live the story. And so on it goes. Much is

never decided until I am faced with writing particular scenes. That’s

when it gets really hard.

Talking to the North Adams Transcript before appearing at the David G. Hartwell ‘63 Science Fiction Symposium at Williams College as part of a panel on climate change, Robinson commented on science fiction, climate change and our attitude towards it, as well as the relationship between being human and our technology. Some food for thought:

"I often talk about

what young people can do in terms of their careers and in terms of how

they're going to live, what it means for them," said Robinson. "What I

try to do is counter the idea that it means renunciation and suffering

and that they're going to have to live like saints. This is a false

image of how they have to live in the future. The future becomes a

project for them, in the existential sense. They've built their lives

around something that has an actual meaning. Life has meaning again and

climate change, rather than just being disastrous, is actually being

given a meaning to our civilization's existence."

[...] The reaction to climate

change is just part of Robinson's wider concerns -- the human

relationship with science and technology and how we negotiate a balance

so that it does less harm than good. It's something that Robinson thinks

is one of the most ingrained issues of our existence on this planet.

"My most recent novel, which was set in the Ice Age with

Paleolithic people, makes the point in a different way that we are a

high tech species," he said. "Technology is actually one of the first

things we did as homo sapiens that really made homo sapiens. In other

words, we really started using tools and that's what co-evolved us into

being who we are, so we have to admit that. It does become an ecological

matter of can you use your technology to stay in a healthy balance with

the biosphere at large now that we're a global civilization and have

immense powers compared to any times in the past."

[...] "I often think that

bad category errors are being made," Robinson said. "By that I mean

that often -- and GMOs are a great example -- people are scared and

angry at the idea, but it turns out that the operation itself is very

little different between that and hybridization and the stuff that we've

been doing to plants our entire lifetime as a species, so that the

anger has been misplaced. It's not genetic engineering, it's capitalism.

Ownership of the natural world, people are very angry at that, and then

they get angry at science instead of the business system, the economic

system, that we live in. This slippage, this is where the left is so

messed up, liberal sentiment in the United States -- and I'm totally

onboard with that, that's what I am myself -- but when they get angry at

science when it's actually capitalism that they're angry at, they're

making a terrible error."

[...] "You've got to

properly assess the risks, then you've got to do a true cost/benefit

analysis of how much we're willing to pay socially and economically to

manage the risks that we're creating. These are complicated things that

aren't fully understood. And we have to start make distinctions between

science and capitalism, and supporting the one and attacking the other,

because I think of science as a public project for the public good and I

think of capitalism as just privatization and an oligarchy and

injustice. This is my own political ax to grind. It's something that

drives a lot of my stories."

In an interview for LiveScience, Robinson talked about science fiction and went through the different kinds of SF: near-future, future history, space opera, utopia, political/economic:

"All sci-fi put together gives you a feel for the future that is fuzzy" [...]

The futures are not always compatible, but "taken together, they give

you a kind of weather forecast," Robinson said.

Of course, reviews for Shaman abound!

Alan Cheuse's review for NPR also aired on the radio.

Fellow writer Cecilia Holland reviewed Shaman for Locus:

Writing historical fiction is a rite of memory, of recovery – to imagine

what the few surviving data can no longer tell us: how it was to live

in another time. Stan Robinson has always been a writer of huge ambition

– he owns Mars, after all – and in taking on this theme, he has another

huge purpose: not to tell us what this most ancient of human worlds

was, but somehow, through the act of fiction, to make us remember. This

is what we were once. This is our true nature, indivisible from all

nature; what it means to be human, then, and now.

On the whole, I suppose the story’s on the slight side, but what narrative drive Shaman perhaps

lacks, the author more than makes up for with his masterful handling of

its central character, whose coming of age from boy to man and from man

to shaman the novel cumulatively chronicles. This is in addition to

Robinson’s carefully layered characterisation of the others Loon looks

to, like Heather and Elga and Click, whom I loved. To a one, they are

wonderfully done.

But if Shaman is about any single thing, it’s about legacies

lost and left. Of particular significance, then, is Thorn, the

long-suffering so-and-so in charge of painting the caves and preserving

the memories of the tribe he tends. [...] we arrive, at the last, at the heart of the matter, for it is he who asks the question Shaman answers: what do we leave behind, and why?

Adam Roberts, massively readable, for Arcfinity:

The overwhelming sense of paleolithic life one gets from reading this

novel is what it is like subsisting on little or no food for long

stretches. What it feels like when your belly button is a fingers-width

away from your spine. How Elga’s substantial breasts simply melt away

from the withering lack of calories. One thing the novel does rather

brilliantly is have you empathising with an aesthetic of female beauty

that inspired the maker of the celebrated Venus of Willendorf figurine.

(Also, this had to happen.)

Val's Random Comments (a frequent Robinson reviewer):

While many of Robinson's characters can opt for a (temporarily) more

primitive lifestyle, Loon doesn't have a choice. He simply know any

better. What keeps him busy are the most primal concerns of all: food,

shelter and sex. What struck me about this novel was the sharp contrast

with what is probably the most famous series of novels set in

prehistory; Jean Auel's Earth Children

series. Where she presents life during the ice age as utopian, where a

human being can make a decent living with a bit of planning and a good

set of survival skills, and where paradise is lost after the discovery

of the link between sex and procreation, Robinson's reality is much

harsher and probably closer to the truth. Loon suffers periods of

starvation followed by a summer of plenty. His weight fluctuates

considerably over the course of the seasons and he is always aware of

the upcoming lean season. All things considered it is a miracle he still

has time for his more spiritual pursuits.

Forbidden Planet, Malachy Coney:

The learned experiences of the tribe ,the hard won history of survival ,

is passed on through the wisdom and songs of the shaman. More spoken

word than musical theatre. Mostly stories about staying alive, the

acquisition and quest for food. The pursuit of the next meal is all. The

tribe, the clans, pursue the next meal with the greatest of intents and

respect. They revere everything they kill to eat, before and after

death. [...] Thorn the shaman is a grumpy cantankerous and unpleasant old sod who

seems to take delight in tormenting his only pupil, Loon. [...] Thorn knows that even if he manages to pass on his accumulated knowledge

there is the certainty that so much will still be lost. Without a

written record even the spoken and learned wisdom will acquire cadences

of its own, changing in turn the full message passed, little by little

over generations. The Druidic past when guessed at became invested with

romantic ideals it most likely never possessed. Wisely Robinson puts at

the heart of the shaman’s lore a savage logic that could in actuality

serve the needs of the clan. He creates very complex and personal

conflicts within the clan.

Though the plot is straightforward bildungsroman material, Shaman

brims over with some of the finest writing Robinson has yet produced. It

immerses us in a vivid world of flickering lamplight and intricate

ritual, a life of “smoke and mushrooms and dancing and flagellation”.

[...] Of course, this is not to say that the novel is a dry recitation

of anthropological facts. Far from it. The pack’s sexual politics are,

for example, as developed and intricate as any contemporary society. [...] Meanwhile, its members transcend their somewhat stock origins and

achieve a credible life of their own. In particular, Robinson’s shamans

are a colourful lot who consume heroic quantities of “berry mash” to

“launch their spirits out of their bodies”. They are part-medicine men,

part-counsellors, and deeply immersed in oral literature. Through them the author rejects the so-called Great Leap Forward,

eschewing any notion of a sudden cognitive revolution in favour of the

slow accumulation of human knowledge over generations. “It’s fragile

what I know,” Thorn tells Loon. He must pass on his wisdom the

same way embers from an old fire are preserved to light a new one. In

fact, this is exactly the lesson which Loon and the reader learn on the

first night of the boy’s wander: the difficulty of kindling a fresh

spark, a symbolic new idea.

[...] For Robinson, stories are about optimism and the belief that life

will always go on. Shaman is no different. It is an intelligent, and at

times mesmerising novel. The perfect book for archaeology buffs, those

who love the outdoors, or readers who prize an unusual perspective in

their fiction.

More interviews & reviews soon!

September 14, 2013

SHAMAN!

SHAMAN is out! Let the third wind carry you to Loon and take a trip to ancient Urdecha!

Above: Hand prints at the Chauvet cave (from EvoAth)

Kim Stanley Robinson's main inspirations for this novel have been the discovery of Ötzi the frozen man in the Alps in 1991, with all his alpine gear, and his own personal experiences of living in open spaces while hiking in the Sierras.

When asked to write about exploration for Slate.com, Robinson wrote about this experience of hiking in the Sierra Nevada of California, through rough off-trail terrain, with whatever partial help maps and GPS can give you: "The Map Is Not the Territory". There's some great landscape writing in there.

Just last week we were crossing from the west shoulder of the Gemini to Upper Turret Lakes, on a broad ridge in the sky, which our topo map showed as smooth. But we could see a drop ahead, blocked by a knob that kept us from seeing how deep the drop was; it could have stopped us, sent us back ever so many miles. And there was a notch up the other side of the drop that looked vertical. Two potential stoppers, and we hurried along that ridge round-eyed, hearts pounding, ignorant of what we would find. It was an ancient feeling, a primate thrill. Exploration was alive.

As with Galileo's Dream, also based on past events, there is going to be loads of material to explore at in the internet and off about the setting and the the lives of the heroes of Shaman!

LiveScience interviewed Robinson on Shaman and its themes, its background, and the amount of real "certified" science that he put in it: "Looking 32,000 Years in the Past".

LiveScience: What kind of research did you do when writing "Shaman?"

Kim Stanley Robinson: Mostly, [I read] the relevant materials. There was also that Werner Herzog movie, "Cave of Forgotten Dreams." I got the DVD of when it became available, because it's that very cave that I'm writing about. I have an archaeologist friend who lives across the street who read the manuscript and friends at [the University of California], Davis connected me up with an anthropologist that works with preliterate cultures in New Guinea highlands. Also, my own snow-camping experiences just [gave me the] direct experience of being out in the snow with camping gear only. That was a big help. It comes down mostly to reading the relevant scientific literature and also other prehistoric novels that existed before mine.

Robinson puts Shaman in continuity with his overall science fiction work:

LS: Does this book have a place in your science fiction work?

K.S.R.: It has been part of the project all along for me — this science fictional project of what is humanity. What are we? What can we expect to become? How do we use technology? Is there a utopian future possible for us? In all of these questions, it becomes really important [to understand] how we evolved to what we are now and what we were when we were living the life that grew us as human beings in the evolutionary sense.

Apart from the interview, LiveScience also did an article on "The Real Science of Kim Stanley Robinson's 'Shaman'" that uses some of the same material but offers some new as well.

Above: The writer in his element, at the top of Mount Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from the Slate article

Goodreads also interviewed Robinson, not just on Shaman but on various of his works, taking questions from Goodread members. It's a great read!

GR: Have you ever attempted something on par with Loon's wander?

Kim Stanley Robinson: No, nothing quite like that. It's a ritual initiation into a shaman's life and meant to be an extreme experience. Don't try Loon's wander at home!

GR: You're already known for alternate history, notably The Years of Rice and Salt. But Shaman goes considerably further back. What inspired you to write about the Paleolithic era?

KSR: It was partly the backpacking. When the body of the Ice Man was discovered emerging from a glacier in 1991, it occurred to me that his clothing and gear much resembled the stuff we took with us into the mountains. His materials were different, but the design and function were much the same. This started me thinking about the Paleolithic and the many thousands of years we lived that kind of life, and it became something I wanted to write about.

This stayed a general desire until I learned about the Chauvet Cave, discovered in 1995, with its beautiful paintings that turned out to be 32,000 years old. At that point I felt I had found my story and characters.

GR: Jared Diamond's recent book, The World Until Yesterday, looks to traditional societies for lessons on how to live. Shaman offers a similar look at an older way of life—much, much older. What do you think we can learn from looking backward?

KSR: We can learn how we became what we still are now; this has to be instructive. Nowadays, with our powerful technologies, it feels as if we have detached from nature and can become anything we want, but in fact we are still the same animals we were 50,000 years ago. And we evolved into the animals we were then, and are now, by living a certain kind of life. The more we understand that, and contemplate what it was we were doing in the Paleolithic that we could regard as fundamentally human (meaning the things we did that made us human in the first place), the better we can judge our current range of potential behaviors: Are they good or just the illusion of good? Do the activities make us healthy and happy? Bringing in the Paleolithic can make these questions shift from what might seem mere matters of opinion to a set of physical facts that can't be denied without bad effects in our lives. So I think the Paleolithic lessons can be really useful and profound.

Some reviews for Shaman have come out:

NPR: 'Shaman' Takes Readers Back To The Dawn Of Humankind

Tor: A Moment in Time: Shaman by Kim Stanley Robinson

Though rather more modest in its scope and conventional in its concepts than Kim Stanley Robinson’s staggering space operas, Shaman

tells an ambitious, absorbing and satisfyingly self-contained tale on

its own terms. At once delightful and devastating, it transports us to a

moment in time, reverently preserved and impeccably portrayed... and if

that moment is off in the other direction than this author tends to

take us, then know that he is as adept a guide to the distant past as he

has ever been the far-flung future.

Locus, September 2013, by Gary K. Wolfe

Finally, on a completely different topic, Robinson is featured, with many others, in a BBC show on "After the Gold Rush - The Poetry of California", where he talks about the impact of California's landscape on its writers. The podcast is available here.

Watch out the calendar of events (on the left) as it is updated with events, panels, readings, signings, as we celebrate Shaman!

August 20, 2013

Robinson on optimism, self-actualization and transhumanism

SHAMAN just came out, September 3 2013; but before the host of interviews and readings that that one will involve, some non-Shaman material:

Adam Ford recently interviewed Robinson for 33rd Square (probably during the Humanity+ event last December). This resulted in a fascinating interview where Robinson discusses many of his ideas and worldviews, from science fiction, transhumanism and the role of technology to optimism, Buddhism and self-actualization. It is well worth your time and summarizes many of his interviews in the past few years. The interview is on YouTube in 5 short parts, below is Part 1:

Kim Stanley Robinson is featured on the very KSR-focused cover of the August 2013 issue of Locus Mag. The magazine features a conversation with Stan, "Making Worlds".

Excerpt:

From the beginning of my career, I’ve done the Solar System set a few hundred years in the future. So for this new one, I stole from myself: the city of Terminator on Mercury comes from The Memory of Whiteness. But when I tried to describe the rest of the Solar System, it began to get so detailed it was goofy. That was when I thought of Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner, and how he had used John Dos Passos’s USA Trilogy methodology. My lists, extracts, and quantum walks all have their equivalent in Dos Passos. Using his method clarified things a lot. With it, I could tell the lovers’ story, and the mystery they’re involved in, and all the rest of it. Instead of using the typical expository lump, which is the famous problem of science fiction writing (and I’m often criticized for being a monster in that regard), I was able to chop the exposition into little bits, make it more something like little prose poems scattered through the text. It’s sort of an internet version of the Encyclopedia Galactica of the 1950s, which I think was one of the things people loved about science fiction, actually: learning about a far-flung civilization by way of direct description. But my impression now is that a lot of new readers don’t remember Stand on Zanzibar, and never read the USA Trilogy, so they think I’ve done something new and peculiar. Some have complained, but I feel those people are a little too narrow-minded about what the novel can be.

2312 was translated in Spanish by long-time KSR and SF publisher Minotauro. Robinson was interviewed by El Cultural, where he talks among other things of Mondragon, on course.La primera vez que oí hablar de Mondragón y su sistema de cooperativas fue cuando estaba escribiendo mis libros de Marte, es decir, a finales de 1980 y principios de 1990. Mondragón es ampliamente conocido en las comunidades teóricas izquierdistas de todo el mundo, ya que representa un ejemplo vivo de una alternativa al capitalismo estándar. Es famosa en esos círculos, como el estado de Kerala en la India, la ciudad italiana de Bolonia, el experimento de autogestión en Yugoslavia, y algunos otros ensayos de alternativas. Ahora, tengo que confesar un intenso interés por lo que ha ocurrido en Mondragón en medio de la actual crisis del euro desde 2008, y la crisis de desempleo de los jóvenes en España, esta noción creciente en todo el Mediterráneo de que puede haber una “generación perdida”. ¿Cómo se ha desarrollado en Mondragón? ¿Se ha mantenido sólido en la crisis, o no? ¿Hay lecciones allí que el resto de España y del mundo pueden aprender? Espero aprender más de lo que he podido averiguar.

A great find: artist Stanley Von Medvey depicted a scene from 2312 (larger there), probably Swan in one of the savannah terraria! I don't know if this was commissioned for some reason or whether the artist made it for his own enjoyment.

On the Huffington Post, Rabbi Lawrence Troster ponders about climate change activism (Climate Reality Project) and the historical period in 2312 that Robinson termed "The Dithering", 2005-2060, during which political lockdown and behavioural inertia resulted in a lack of action against climate change.

Some more 2312 reviews: Ancient Logic | City of Tongues

Some recent events:

Robinson was at the WorldCon in San Antonio, Texas, from August 29 to September 2, 2013: " LoneStarCon 3 ". The Hugos were announced there, but 2312 did not take the win.

Barnes & Noble SHAMAN reading & signing in San Antonio, Texas

Tuesday, September 3, 7 p.m.Author Event: Kim Stanley RobinsonThe New York Times bestselling author will make an appearance at Barnes and Noble San Pedro (321 NW Loop 410 suite #104) for his novel, “Shaman.” Robinson is most known for his Mars-trilogy which has won many awards including the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award.For more information, visit barnesandnoble.com.

Some upcoming events:

Barnes & Noble SHAMAN reading & signing in Dallas, Texas -- TODAY!

Author EventKim Stanley Robinson, the bestselling author of science fiction masterworks such as the Mars trilogy and 2312, will be joining us to discuss and sign his new novel Shaman, a powerful powerful coming of age story set 30,000 yrs ago. Come meet the author!Wednesday September 04, 2013 7:00 PMLincoln Park, 7700 West Northwest Hwy. Ste. 300, Dallas, TX 75225, 214-739-1124

Robinson will be a speaker at the Library of Congress in Washington DC on September 12 2013, on "The Longevity of Human Civilization: WIll We Survive our World-Changing Technologies?"

Will human civilization on Earth be imperiled, or enhanced, by our own world-changing technologies? Will our technological abilities threaten our survival as a species, or even threaten the Earth as a whole, or will we come to live comfortably with these new powers? Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology David Grinspoon convenes scientists, humanists, journalists, and authors to explore these questions from a wide range of perspectives, and to discuss the future of human civilization in an anthropocene world.

Full event

Date: Thursday September 12, 2013 from 8:30 a.m. – 4:30 p.m.

Place: The John W. Kluge Center, Room 119, Thomas Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA

Robinson will also be participating at A Science Fiction Symposium at Williams College in Massachussetts on October 24:

Please join us on October 22nd, 23rd, and 24th for a Science Fiction Symposium that will include readings, panels, and lectures by leading writers and thinkers from across the United States. October 24th will include a panel discussion as well as a 4pm Reading. Participants will include Samuel R. Delany, Kim Stanley Robinson, Elizabeth Kolbert, David Hartwell, Paolo Bacigalupi, William Gibson, Terry Bisson, and John Crowley. More information will be coming soon. Sponsored by the English Department, The Margaret Bundy Scott Fund, American Studies, Environmental Studies, Africana Studies and the Oakley Center.

Full event

Date: Thursday October 24 2013, 4pm to 9pm

Place: Griffin Hall, 3 844 Main St, Williamstown, MA 01267, USA

More SHAMAN-related material very soon!

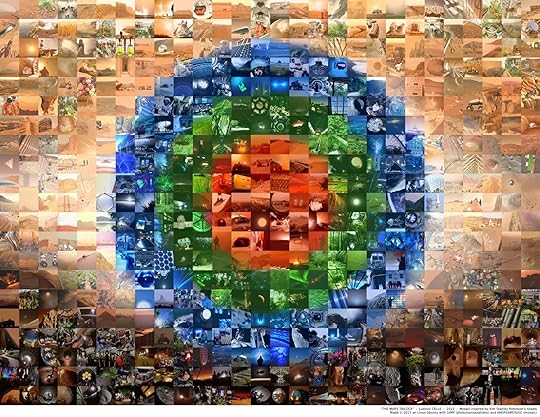

Art corner: Ludovic Celle's "Mars la rouge"

You could say Red Mars's 20th anniversary is being celebrated in Grenoble, France, close to the Alps!

The public library of Grenoble hosts the exhibition "Mars la rouge" ("Red Mars" in French) with many of Ludovic Celle's photomontages around the future colonization of Mars in general, and on the world of Kim Stanley Robinson's book more specifically. The exhibition opened in June and (with a summer break in July) is still open for the world to visit and marvel until September 7th. So take your sailboats, space elevators and hyperloops, and come to Grenoble!

The work of Ludovic, a good personal friend of mine, have been featured on KSR.info before.

The montages -- made on open source software and photos on the public domain (a very conscious choice on behalf of the artist) -- are large and feature marvelous wild landscapes you should be able to see when exploring Mars, with the addition of the beginnings of a human presence, be it a rover dwarfed by the Noctis Labyrinthus canyons, a small tent holding some green inside, the plume of a distant mohole, or the thin line of the space elevator.

The images are accompanied by a short text explaining the artist's inspiration from Robinson's book, but there are many influences melding here: the crude realistic shots of NASA exploration missions and the ISS, the landscapes of Jordan or the United States, the modern efforts at urban agriculture, the process of discovering the very city you live in, and personal journeys. A book exhibit with several of Kim Stanley Robinson's novels along with some quotes from Red Mars complete the expo.

The largest exhibit is definitely the Mars trilogy photomosaic, at 2.50 m wide (about 8 feet) and featuring some 600 pictures, ranging from the technical engineering work to the entirely mundane of building a place to live in. More on the mosaic here.

Local media Cause Toujours also interviewed Ludovic Celle. The video in French has been subtitled in English and can be viewed below (subtitles can be turned on by clicking at the bottom right of the video); Ludovic talks about his inspiration, his work process, his feelings when reading Robinson's books, his other ecology-focused interests that feed and at times can clash with his passion on the subject of space exploration.

More on the expo (with pictures of the expo and of the montages themselves):

On Da Vinci Mars DesignOn Ludovic Celle's site (in French)Linux Academy article and interviewOn Ludovic Celle's FacebookOn the Grenoble public libraryLudovic promises more expos of his work in the future, on urban ecology and agriculture, and, why not, on Green Mars!

July 13, 2013

Coming Soon: SHAMAN

"This is how we always start

It's time to be reborn a man

Give yourself to Mother Earth

She will help you if you ask"

Kim Stanley Robinson's next novel, "SHAMAN", is coming less than two months from now, on September 3 2013!

Watch Stan himself introduce his novel:

Robinson, a Davis, California, resident and fellow science fiction author Tobias Buckell participated in UC Davis' 44th annual Whole Earth Festival. They were interviewed by Davis Enterprise:

“There are a lot of people who say, ‘If we have to change capitalism,

well, OK, we’re doomed, because we can’t change capitalism.’ But we

can. It seems to me that science and democracy together are actually

capable of changing the laws for the sake of our survival and the sake

of our kids and their descendants.”

Robinson said that he disagreed with scientists resolved that the

best tack is adapting to climate change, rather than trying to halt it

or reverse course.

“They look at me like I’m an old hippy utopian idiot and say, ‘No

matter what you think, we’re at 400 parts per million. Nobody is

stopping using carbon at any successful rate. In fact, it’s going faster

than ever. We’re just being realistic, and you’re the one being

unrealistic.’

“And then I say, ‘No, no, no, you’re the one who is being

unrealistic. You’re being pseudo-realistic, because you’re saying the

future is certain.’ I’m saying as a science fiction writer, nothing is

certain.”

Most importantly, Robinson and Buckell did a joint panel on climate change, as covered by Steven Rose's blog: "Kim Stanley Robinson: Back to the Prehistoric

Past for a Greener Future", which serves as a nice introduction to SHAMAN:

Robinson read an excerpt from his

novel, Shaman, set in a prehistoric ice age. But this is no pulp-/Hollywood-/ One Million

Years B.C.-inspired novel. Robinson takes his science fiction seriously; he

writes hard science fiction. Strangely, however, Shaman does not

seem to be his typical hard sci fi. In fact, with references to tribal

magicians and mystic journeys one would think it’s closer to fantasy. But,

after the reading, Robinson used the tribe from his this alternate (pre-)

history novel as a model for how modern day humans are capable of planning ahead to save

themselves from future ecological disaster such as an arctic meltdown. He

explained how we can collectively come to solutions to prevent the disastrous

effects of global warming.

During the two authors’ dialog on the subject of climate

change and science fiction, one phrase Robinson kept bringing up was “utopian

societies”. He referred to the primeval tribal society of Shaman as a

model for a more communal future society that can plan ahead to prevent, or at

least reduce, ecological disaster such as a global meltdown of the ice caps.

Robinson explained how such a society could work in a high tech age: by

utilizing clean energy technology and reforming capitalism to make it more

socially just (though not necessarily communist). Through this idea, Robinson

explained the economic implications and necessary reform for an environmentally

responsible society. In the meantime, Robinson is participating in Clarion's Write-a-thon.In related news, the literature and science fiction world recently mourned the loss of one of the best writers of the field and personal friend of Robinson, Iain M. Banks. His last novel, The Quarry, was published barely days after his death in June 2013.

Top image: SHAMAN cover artwork by Michal Karcz, also featured prominently in Orbit Books' Autumn Catalogue 2013.

July 6, 2013

Two Talks: What Is the Future For? & The Literary Imagination

Kim Stanley Robinson visited the Museum of Modern Art in New York in June for a panel discussion, as part of the MoMA PS1’s series of talks "Speculations: The Future is _".

Each did a keynote address. Stan's talk, "What Is the Future For?", greatly summarizes all his latest ideas on science, (post-)capitalism, the utopian process, climate change, the paleolithic way of life, our relation to the physical world... Watch it below!

Watch John Crowley's address and their joint panel together with Q&A, which covers many many topics.

The City Atlas provides a summary of Stan's talk, with a particular focus from the Q&A on cities’ role in participating in a better planned, more sustainable future.

I have often framed this problem as science versus capitalism…For me, science is the effort to try to reduce suffering, the effort to try to make life more comfortable for human beings, to understand the world better and to manipulate it for various human goods…I think of science as a utopian good that can make things better.

[...] I think cities are important because they are so densely populated…and I think that a lot of city life is fairly paleolithic in a strange way because it gets away from the automobile. Cities encourage face-to-face interactions with other individuals, so I like it for that. And I think that rooftops need to be used for urban gardens and that cities need to be greened, less for the auto and more for people and public transit.

Earlier, in May, Stan participated in a talk organized by the newly-opened Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination and the Helen Edison Lecture Series at UC San Diego: "The Literary Imagination". Fellow writer Jonathan Lethem, A C Clarke Center Director Sheldon Brown and Stan discussed the writing process and each other's writing. This event marked the opening of the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination at UC San Diego.

The long discussion includes both writers reading from each other's works, a highlight of the talk and a joy to watch and hear! Lethem read three "Lists" from Robinson's 2312, and Robinson read Lethem's hilarious list "Proximity People" (direct mp3 link).

The discussion also included a very interesting part, separate from the above video, in which both writers discussed a common influence of theirs: Philip K. Dick (direct mp3 link): Dick's social realism, Dick's fantastic elements, Dick's adaptation in films, favorite novels. Robinson famously wrote his PhD thesis on Dick's works, which has been expanded and edited separately as The Novels of Philip K. Dick.

June 29, 2013

Nebula win 2312 + State of the World 2013

The big news is that Kim Stanley Robinson's latest novel, 2312, has won the Nebula Award for Best Novel! This is Robinson's first Nebula win after Red Mars! At the same ceremony, Gene Wolfe was the recipient of the 2012 Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award, and appropriately enough Stan's acceptance speech was centered on congratulating Wolfe as well! As covered earlier, there are more awards ceremonies coming in the rest of the year!

(Nebulas 2013 winners)

This is no longer 2012 and the 'exactly 300 years in the future' setting no longer works, but 2312 is still a new novel -- I've even seen typos from readers mentioning it as 2313! 2312 has also just been released in mass market paperback in the UK and as far as I can tell the USA as well (June 25 2013) by Orbit. It has also just been published in Spanish, for Spain and the whole of Latin America (June 18 2013) by Minotauro.

(Kim Stanley Robinson, Gene Wolfe, David G. Hartwell)

A number of interviews have surfaced on the occasion of the Nebula:

Sword and Laser interviewed Stan at the SFWA Nebulas event, actually a few hours before what proved to be a win! Stan speaks about a lot of his novels, not just 2312 and the Mars trilogy, and in the middle of the SFWA Nebulas Weekend there are a lot of laughs to be had (direct mp3 download).

Big part of the July 2013 issue of Popular Science (print & online) is dedicated to views of the future. It has an extended excerpt from 2312 and an article with predictions on how life will be in the future by various authors, as well as beautiful artwork. Kim Stanley Robinson is featured:

Many problems in travel around the solar system were solved when asteroids were adapted to the task. Thousands of ovoid asteroids were hollowed out so that their insides were empty cylinders, and then they were set spinning on their long axes to create a gravity effect inside. Crews and passengers live at one g, well protected from cosmic radiation, and move in orbits around the solar system like giant ocean liners. They never slow down, and catching up to one in a little ferry can be a crushing experience, as your reporter recently learned.

Each asteroid contains a particular biome, filled with the plants and animals from particular landscapes back on Earth. Some are more aquarium than terrarium. If species have been mixed to make a mongrel biome, as has happened on Earth since the first living creatures migrated from one ecosystem to another, the result is called an Ascension, after Ascension Island in the South Atlantic. The island was bare rock until HMS Beagle landed there, and Darwin himself planted a variety of plants which have since prospered.

By a nice coincidence, your reporter’s recent voyage was on the Wegener, an Ascension asteroid composed of plants and animals from West Africa and eastern Brazil. It is a beautiful space, highly recommended, but all the terraria are gorgeous in their own ways—in effect, floating works of landscape art.

Take a trip on one and see!

Robinson talks about what the process was to create 2312 -- from character temperaments to world-building to history to form -- to writer Mary Robinette Kowal:

I had recently written an introduction to John Brunner’s excellent Stand On Zanzibar, which had solved a similar problem by using the method invented by John Dos Passos in his great U.S.A. trilogy. [...] So, I adapted all the strands to my own purposes. My main strand follows my characters Swan and Wahram and Genette. The newspaper columns I turned into extracts from all kinds of unidentified texts, and I cut all these texts into minimal pieces to imitate how we read online, linking from one source to the next as we pursue the information we want. The biographies of famous people I had to alter somehow, because I don’t think pocket biographies of fictional people can be as interesting as the same for real people; so I had my biographies be of moons and planets and big spaceships, as these were in effect historical actors in my story. Then lastly I made the camera eye strand be the stream of consciousness of a quantum computer, put in an android body and let loose in the world for the first time.

Stranger Than Fiction, a podcast from Slate, the New America Foundation, and Arizona State University, has interviewed Robinson about the politics of science fiction, how robots have historically represented wage workers, and why we need to right Earth before we head to Mars: "Mars is a good 23rd-century project" (direct link to SoundCloud).

(Kim Stanley Robinson viewed through his Nebula Award)

The Atlantic also interviewed Robinson prior to the Nebula win, on 2312, science fiction versus futurology, Buddhism, Mondragon co-ops, capitalism, why the current time period is named "The Dithering" in 2312's future history...

Capitalism is a system of power and ownership that privileges a few in a hierarchical way, and it has in it no good controls or regulation concerning its damage to the biosphere, so to deal with the environmental catastrophes bearing down on us, we have to impose our will as a civilization on capitalism and make it do what we want civilization to do now, which is to create a just and sustainable human interaction with the biosphere and each other.

So this suggests legal changes imposed by democratic government, which are more and more urgently needed. The free market can't do it because it isn't free, but in fact a particular legal system completely inadequate to the situation, and the prices we concoct for things are completely unresponsive to physical realities.

So we are in quite a bit of trouble here, because capitalism is a cultural dominant and the current global way of conducting things, world law, and yet completely inadequate to the situation we face.

[...] So it is tricky work. But I am saying that democracy and science are stronger than capitalism. It is an assertion we are going to have to test to see if it is true or not. It will be a fight. It is the fight of the 21st century like the fight against totalitarianism was the fight of the 20th century. Indeed we did not definitively win that fight, because capitalism is a new kind of totalitarian system, fully capable of buying up democracy and science, and trying now to do so. So it is a tricky fight, but necessary work for us all.

A video of the Humanity+ conference from last December found its way to YouTube. Watch Stan argue for "Humanity minus" in front of a crowd veering more towards transhumanism and the high-tech cyborg.

Kim Stanley Robinson was also invited on a reading of "The First Woman on Mars" by Ron Drummond on the occasion of the release of #13 of White Fungus, a Taiwan-based magazine (Saturday, May 4, 2013 from 3-5pm Reading from “The First Woman on Mars” by Ron Drummond Conversation with Kim Stanley Robinson, author of the Mars Trilogy Venue: KADIST, 3295 20th Street, San Francisco, CA 94110):

Contributing author Ron Drummond read from his essay/fiction hybrid, “The First Woman on Mars,” a story that proposes an original Mars settlement scenario with the potential to serve as the inspirational and “dramatic centerpiece” to unite all human endeavors in space. He was joined by Kim Stanley Robinson, the science fiction writer and award-winning author of the Mars Trilogy and 2312. Together they discussed the social, economic, and political implications of the human push into space and efforts to colonize Mars, as well as the ecological and sociological sustainability of life on the red planet and elsewhere in the solar system.

Video of the Drummond reading.

Video of Stan on the idea of living on Mars.

Some additional reviews for 2312 are still popping up: Breaking It All Down (video); Dark Matter; TPI's Reading Diary; and an article on reviews bias by the Economist.

Most notably, Kim Stanley Robinson participated in the publication by the Worldwatch Institute's "State of the World 2013: Is Sustainability Still Possible?" The Worldwatch Institute is a research institute/think tank: "Through research and outreach that inspire action, the Worldwatch Institute works to accelerate the transition to a sustainable world that meets human needs. The Institute’s top mission objectives are universal access to renewable energy and nutritious food, expansion of environmentally sound jobs and development, transformation of cultures from consumerism to sustainability, and an early end to population growth through healthy and intentional childbearing."

"State of the World 2013" is a large book that covers large issues with contributions from many experts:

The first section, The Sustainability Metric, explores what a rigorous definition of sustainability would entail, helping to make this critical concept measurable and hence meaningful.

[...] The second section of the book, Getting to True Sustainability, explores the implications of the gaps that remain between present realities and a truly sustainable future.

[...] And so the book’s third section—Open in Case of Emergency—takes on a topic that most discussions of sustainability leave unsaid: whether and how to prepare for the possibility of a catastrophic global environmental disruption.

Stan contributed with a chapter of his own: "Is it too late?"

The book and its concepts were presented on several occasions in the USA and Europe. On April 16, there was a State of the World 2013 Launch and Symposium at Washington DC, with panels by: “Beyond Sustainababble” by Worldwatch President Robert Engelman, Panel on “Getting to True Sustainability,” Panel on “Getting Through the Long Emergency,” Keynote by science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson, and Closing Reflections by Town Creek Foundation Executive Director Stuart Clarke.

The whole can be seen as a playlist on YouTube (Robinson's video only).

The authors also spoke shortly one-on-one videos (playlist; Robinson).

The same theme, "Is it too late?", was used in a Robinson article in The Sacramento Bee:

No. It is not yet too late. It is physically possible to shift infrastructures, technological arrays and social systems in ways that would make them so much cleaner than what exists now, especially in carbon terms, that extinctions would not soar, food shortages would not occur, and 7 billion or even 9 billion humans could share the planet with other living creatures in a healthy way. But that's not easy to do. We will do some things wrong. There will be human suffering, there will be suffering among the other creatures on Earth. There will be extinctions. We are going to do damage in the 21st century, possibly big damage. And unfortunately, unlike Wile E. Coyote, we won't get infinite chances to fall and try again. So the question should be changed from the disempowering question, "Is it too late?" to, "How much damage will we let happen?" Then we could flip that revised question to its positive formulation: "How much will we save? How much of the biosphere will we save?" That's the real question.

Robinson also recently spoke to students of Davis High School -- funny to read him described as "local science fiction author", KSR right down the street!

A man with greying hair and rectangular glasses stands in front of an auditorium of students in the Davis High IPAB on May 7. He’s wearing ordinary clothes: a tucked-in plaid collared shirt and slightly wrinkled khakis. The only visible sign of his unique and spirited character is shown in a leather belt with a bright blue stone set into the buckle. The auditorium quiets to hushed whispers and then silence under the observant gaze of Kim Stanley Robinson.

(Photos by Carrie S, and Omnivoracious; also, Robinson and Joe Haldeman)

Kim Stanley Robinson's Blog

- Kim Stanley Robinson's profile

- 7449 followers