Grace Tierney's Blog, page 15

January 16, 2023

Anecdotes and Antidotes – a Word History

Hello,

As you may be aware, I love getting suggestions of words to investigate from readers of the Wordfoolery blog. You can do that here, if you’d like. Mary suggested antidote recently and I thought I’d throw in anecdote too as it can be fun to see if two seemingly similar words are connected.

Let’s start with antidote. It is a remedy to counteract a poison and the word has been with us since the 1400s. It was originally antidotum and came from Old French antidot, Latin antidotum, and ultimately from Greek antidoton. Antidoton translates literally as “given against” and is created from anti (against – a prefix which is used in plenty of English words) and didonai (to give). Didonai comes from a Proto IndoEuropean root word do (to give).

Didn’t make it to the antidote in time

Didn’t make it to the antidote in timeThe story of antidote is pretty straightforward. Anecdote, as you’d hope given the meaning, has more of a story.

Anecdote has two somewhat conflicting definitions. The one I’d use is that it’s an short amusing story about real people. It can also be an unreliable account, or one regarded only as rumour.

Anecdote has been with us in English since the 1600s to describe secret or private stories. It was the 1700s before it gained the meaning of a brief amusing story. We borrowed the word, and the spelling, directly from French in the 1600s. It had arrived there from Medieval Latin as anecdota and before that from Greek anekdota (things unpublished). When you break it down you find the link to antidote.

Anekdota is formed from an (not) and ekdotos (published). Ekdotos is formed from ek (out) and didonai (to give), again from the Proto IndoEuropean root word do (to give). So yes, the dote in anecdote and antidote is the link between the two words. You can’t escape the Greeks in the world of English etymology.

I can’t leave anecdote without giving the perfect, and original, example. The word was used as a title for Procopius’ book “Anecdota” written around the year 550. Procopius was a scholar who accompanied the Roman generals during Emperor Justinian’s wars. Riding with the army he witnessed massacres, battles, and mutinies. He became the main Roman historian of the 6th century and published many books, all of them favourable to the emperor’s reign.

The “Anecdota” however was not published during his lifetime and was far from positive about the emperor. In fact it was packed with court gossip. The book was discovered centuries later in the Vatican library and published in 1623 – bringing the word into popular use and ultimately to the English dictionary.

Like modern “tell all” books, Procopius took his chance to expose the secrets of his emperor’s reign and portray the private lives of the leader, his wife, and his generals. The emperor is shown to be cruel and incompetent and in one passage he even claims he was possessed by demons. Theories abound on why Procopius took the risk of writing the book. He may have been waiting for the main characters to die, in order to avoid retaliation (as he mentions in the book), or he could have written it as insurance so that if the emperor was overthrown he could survive the change.

Procopius never published the “Ancedota“, but thanks to the Vatican Library we can read it today and use the word, without fear of reprisals from demon-filled emperors.

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace

January 9, 2023

The Pun-filled History of the Phrase Couch Potato

Hello,

I’ve been gathering a collection of useful word books in recent years and this week’s term, couch potato, is thanks to one of them – “The Oxford Dictionary of New Words” (Oxford University Press, 1991) which I picked up second-hand. I’m familiar with the idea of a couch potato being a person who likes to lounge on the sofa with TV remote control in hand, but I had no idea we knew exactly who coined the phrase, or that there were clubs, puns, and even trademarks involved.

Let’s do the basics first. Couch has been in English since the mid 1300s as a word for a bed, borrowed from Old French couche (bed or lair) thanks to the verb coucher (to lie) and ultimately from Latin collocare (to lay in place) which is from com (with) and locare (to place). Locus is the Latin for place, which is also imported into English – think about local, for example. The idea of sitting on a couch arose in English from the mid 1400s, a long seat which you reclined upon. It became associated with psychoanalysis in the 1950s.

I had no idea of the differences between various words for couch, so I’ll include them here. Couch has the head end only raised and half a back. A sofa has a full back and both ends raised. A settee has a full back but may omit the arms. An ottoman has neither back nor arms. A divan has neither back nor arms but rests against a wall, giving some back support. In my experience couch, sofa, and settee have been used interchangeably. How about you?

Potato joined English in the 1560s from Spanish patata and before that from batata, a word in the Carib language of Haiti. The word was imported alongside sweet potatoes which were grown in Spain at that time and later in Virginia, America by 1648. If you see potato mentioned in English up to the mid 1600s, it was sweet potatoes they are talking about. The common white potato arrived in Europe from Peru and was given the same name due to their visual similarity.

The first potato arrived to Europe and Pope Paul III in 1540. They were grown initially as ornamental plants in France (there’s a wonderful story about Parmentier and his role in encouraging the French to eat potatoes – I covered this on my radio spot). They arrived in Ireland, according to tradition, thanks to John Hawkins in 1565.

Other languages had fun with naming this new vegetable. German’s Kartoffel comes from truffle in Latin and Italian. French’s pomme de terre (earth apple) always amused me and Swedish has jordpäron (earth pear). Dropping something like a hot potato dates to 1824 and the one potato, two potato counting rhyme is recorded in 1885 in Canada.

A couch potato in its natural habitat

A couch potato in its natural habitatThe couch potato term dates to 1976. It is based on the idea that a person shaped like a potato spends most of their time on a couch. It was coined by American Tom Iacino via a pun. The original American term was boob tubers because the boob tube was slang for TV there. In Britain a boob tube was a short stretch fabric top for women. Then cartoonist Robert Armstrong drew a sketch of a potato (the best known tuber vegetable) reclining on a couch watching a TV and we went from boob tubers to couch tubers and couch potatoes. He also formed a club called the Couch Potatoes and registered the term as a trademark in 1976.

Robert popularised the term and sold couch potato merchandise but claimed it was Tom who had coined it when asking to speak to another member of the club on the telephone. Robert campaigned to raise the self-esteem of couch potatoes in an era of growing emphasis on physical fitness and even went as far as to say “watching TV is an indigenous American form of meditation” in a 1988 interview in “Parade”.

I’m not sure about that claim and I love getting out for a walk, but I’m always pro-potato. After all my unofficial family motto is “I never met a carbohydrate I didn’t like”.

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace

p.s. I’ve already covered the origin of the word spud, if you’re curious.

January 2, 2023

Wishing you a Nifty New Year

Hello and Happy New Year,

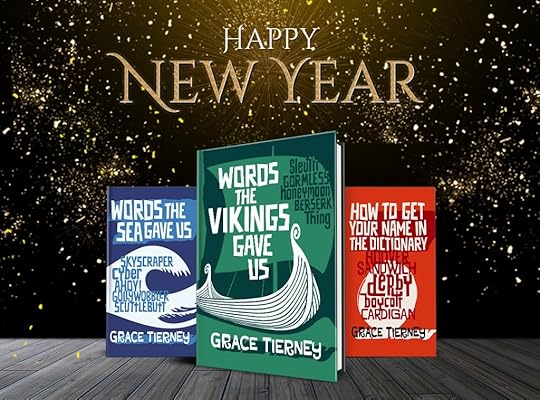

I’m starting my fifteenth year of writing about unusual English words and their histories today. I haven’t run out of words yet and I’m accumulating dictionaries and reference books, as well as slowly filling a shelf with my own books. Thanks for joining me on the Wordfoolery journey.

This week’s word is nifty, because I like how it sounds. It is defined as good, skillful, effective, attractive, and stylish so I hereby wish you a nifty new year.

Happy New Year from Wordfoolery!

Happy New Year from Wordfoolery!Somewhere last year I stumbled upon the delightful fact that nifty is short for magnificent (sadly I didn’t jot down the source) and it charmed me. Magnificent seems so formal and impressive whereas nifty has a chirpy upbeat casual vibe. They are unlikely cousins. However I’m not a carbon copy of all my cousins, we just share familial roots, like nifty and magnificent.

Nifty entered English in the late 1800s to describe something or somebody as being stylish or attractive. Some believe it may have come from theatrical slang, but an early use of it was in a poem by Bret Harte (1836-1902, American poet and short fiction writer) who claimed it was a short form of magnificat.

The magnificat is a hymn or speech by the Virgin Mary in the Christian gospels. The word joined English around 1200 from Latin magnus (great) and facere (to make or do). The word is borrowed from the opening of the Mary’s speech in Latin. It is hard to see how nifty is a shortening of this solemn religious word, although both relate to things or people being great.

An almost parallel word to magnificat is magnificent. You may describe a stylish person as nifty or magnificent but it’s hard to see you saying somebody is magnificat. Some guess that nifty is simply formed from other similar words like natty (stylish) or spiffy (excellent).

Magnificent has very similar roots to magnifcat, in fact. It entered English in the mid 1400s from Old French to describe somebody as being glorious, great in deeds. The French word again comes from Latin magnus (great) and facere (to make or do). By the 1500s magnificent was being used to describe a splendid life in grandeur and by the 1700s it was an exclamation expressing admiration or enthusiasm. The hop from there to nifty isn’t too hard to make.

Without a time machine and the ability to check with Bret Harte whether he said magnificat when he meant magnificent we may never know the true origin of nifty but in the meantime we can enjoy it and use it.

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

December 26, 2022

The Festive History of St Stephen’s Day / Boxing Day

Hello and Happy Saint Stephen’s Day!

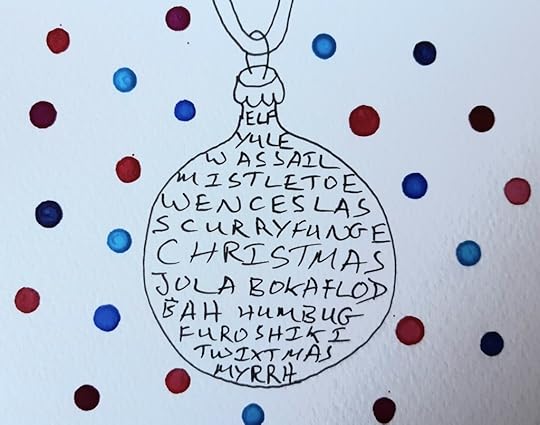

Regular blog readers will know that I’m working on a new book “Words Christmas Gave Us” for release in 2023. As my blog post day this year falls on the 26th of December it feels right to share a draft extract from the book relating to this special day.

{Extract from “Words Christmas Gave Us” by Grace Tierney, copyright 2022}

Boxing Day / Saint Stephen’s Day

This entry will be a contentious one for any Irish reader so let me be clear before the shouting begins. Both these terms relate to the same date, the 26th of December. Boxing Day is the more common term in Britain, while Saint Stephen’s Day is adhered to by most living in Ireland. If you want to provoke a Christmas argument, try using Boxing Day to anybody Irish.

Boxing Day does have a charming history behind it. The term originated in the U.K. and is celebrated in several former British colonies such as Australia and Canada.

Since the Middle Ages, alms boxes were placed in churches to gather donations for the needy. The boxes were opened on Saint Stephen’s Day and the contents distributed, thus making it Boxing Day.

As early as the 1600s (it was was mentioned in Samuel Pepys’ diary) it was customary for tradespeople to request tips for good service throughout the year on the first weekday after Christmas (often Saint Stephen’s Day). Box in this sense referred to a gift, although in some cases the box was a literal box which the tradesperson or apprentice cracked open at the end of the day to count their riches.

The wealthier members of society gave their servants the day off, possibly with a Christmas bonus, and the servants would bring their own boxes (gifts) home to their families.

The association of gifts to tradespeople has continued up to the present day, although perhaps less commonly now. My mother always gave a festive gift to the bin collectors (garbage men in American English) and postman (mailman), for example, and it seems only right to recognise the hard-working delivery people as they work long hours during December.

Who was Saint Stephen though? He was the first martyr of the Christian church, stoned to death for his faith. The 26th of December is his feast day. In art he is usually depicted as a young man carrying a small church building.

[end of extract}

Other Christmas words associated with this day are the Wren Boys, Wenceslas, and pantomine, all explained in the book, but they’re stories for another day.

Until next time, Merry Christmas and happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

December 20, 2022

The Deadly History of Mortgage

Hello,

Less than a week until Christmas and I’m writing about the word history of mortgages. My daughter asked me about it the other day. She reckoned it had to be related to death because mort means death. I promised I’d investigate. It’s not festive, or at least, not entirely. I’ll explain that later.

A mortgage is a “legal agreement by which a bank, building society, etc. lends money at interest in exchange for taking title of the debtor’s property, with the condition that the conveyance of title becomes void upon the payment of the debt.” Basically the lender owns your home until you finish paying off the debt.

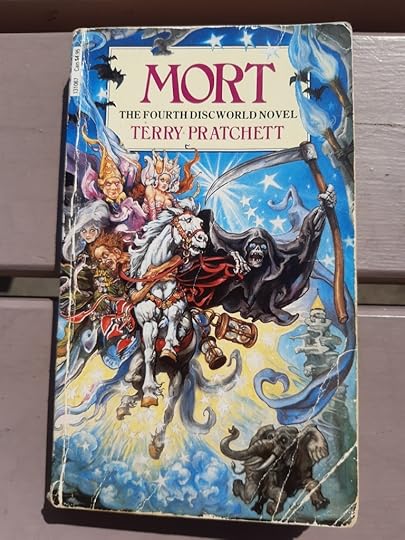

She knows Mort means Death thanks to this wonderful book

She knows Mort means Death thanks to this wonderful bookThe word mortgage reached English in the late 1300s when it was spelled morgage. English had borrowed it directly from Old French mort gaige. This translates literally as dead pledge. In Modern French you would use hypothèque instead.

My daughter was correct, the mort part comes from dead. This is the same way we get mortal, and immortal, of course. Gage means pledge in this context. It could be a pledge of battle, security, or payment and it also leads to the word wage for a salary.

The mortgage was called a dead pledge because the deal itself dies when the debt it paid or when payment fails and the lender takes the home permanently. It doesn’t mean you have to keep paying until you die, although anybody who had ever paid a mortgage will have had that feeling at some point during its term.

The Old French word mort comes from Latin mortus (dead) and the verb mori (to die). Before that it came from a Proto Indo European root word mer (to rub away, to harm, to die) which does lend a little history to the gangster slang of rubbing out your enemies and may make you look askance at your eraser.

Now for the (admittedly tenuous) link to this festive time of year. Mortgage lending was the occupation of one very famous Christmas character – Mr. E. Scrooge. Appropriate as he was visited by the dead on Christmas Eve.

Until next time, Merry Christmas and happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

Happy Christmas 2022! A selection of fun Christmas words from Wordfoolery

Happy Christmas 2022! A selection of fun Christmas words from Wordfoolery

December 16, 2022

Wordfoolery’s Favourite Books of 2022

Hello,

I love reading as much as I love unusual words. I have an annual tradition to look back at my reading (62 books so far) during 2022 with help from my Goodreads account. Here are ten of my favourite books of the year. They’re not all recent releases, as books wait in my Towering To Be Read Pile and because I’m still working my way through the 501 Books to Read Before You Die List (my favourite from that this year was “The Periodic Table” by Primo Levi, a memoir of his life in chemistry). I’d recommend any of these books. If you order through the links provided, a tiny fee is paid towards supporting this blog.

If you prefer posts about the history of unusual words, normal service will resume next Monday.

They’re listed in random order. I can’t rank books, I love them too much.

The Man Who Died Twice – Richard Osman

Another twisty tale with the four feisty elderly detectives. Cosy but fun. Very well observed on the older characters and about time we have more of them in fiction.

This is Going to Hurt – Adam Kay

Witty, engaging, and thought provoking diary of a junior doctor in the UK. One warning – might avoid if you’re currently pregnant as the details are graphic. He is scathing on homeopathy (as it is mostly water the only thing it treats is thirst).

Engaging coming of age tale set in Viking Age Orkney. It follows Skarfr (bard’s foster son) and Hlif (Jarl’s housekeeper and cursed daughter of a disgraced father) through court intrigues, sea voyages, and a world where dual belief systems still rule society. Great hist-fic.

Jean used my Viking book as a research resource!

The Paris Apartment – Lucy Foley

Another well written and very cleverly structured Lucy Foley murder mystery. Jess visits her brother in Paris. He’s living in one of those elegant tall buildings in the city centre, sub divided into apartments with a concierge for parcels and maintenance. One issue – he’s missing and all is not as it appears in this building.

Lud-in-the-Mist – Hope Mirrlees

Recommended by Neil Gaiman. Early fantasy, and by a female writer too! It has a folkloric quality to a tale of a law-abiding town who dreads incursion by its neighbours, the fairy folk. It reminded me of the Shire in Tolkien’s stories but really it is unique and well worth a read by any fantasy fan. You won’t find dragons here, or mystical rings and swords, but spells, strange characters, and a touching level of heart.

Dark Blue Waves – Kimberly Sullivan

If you love Jane Austen and have always wondered what it would be like to live in her world, this is the book for you. When Janet, an American architecture and literature student arrives in England, she has no idea a cricket ball to the head will send her spinning back in time. The author knows the period really well and it’s charming to watch a modern woman navigate, and enjoy, society and romance in the past. But will she stay with her Mr. Darcy?

A Man with One of Those Faces – Caimh McDonnell

Laugh out loud funny, fast paced thriller set in Dublin and Wicklow (Ireland). Great dialogue and good twists. Can’t wait to read more in this trilogy. Reminds me of Colin Bateman and Christopher Brookmyre (in a good way). I hope Dorothy, the 83 year old gun-toting posh grandmother is in the next book!

H.M.S. Surprise – Patrick OBrian

I love this series. Great nautical detail. If you love the Age of Sail you’ve probably already read these but if you haven’t, get started! This time they sail to India with Jack still seeking his fortune and Stephen still madly in love with Villiers despite her being the mistress of another man. Storms, new crew, sea battles and a duel. What more could you want?

Six of Crows & Crooked Kingdom (duology) – Leigh Bardugo

Six of Crows – Fantasy heist, two words I love to hear. Throw in a great cast in the crime gang and I’m happy. Particularly loved the tank scene. Fabulous writing here, cool character arcs, perfect foreshadowing, a touch of twist and cliffhanger to setup for second book.

Crooked Kingdom – The gang’s back and they’re in trouble as usual. Drama, grief, twists, and heists. Wonderful resolution to the duology.

Lords and Ladies – Terry Pratchett

I’m currently re-reading the entire Discworld series. The heart of Discworld is the city of Ankh Morpork, but I think the soul may be in the stories set in the remote kingdom of Lancre. This one has great structure, we get backstory on Granny Weatherwax (the most kick-ass witch ever), great elf villains, and the ongoing romance of Magrat and Verence (former fool, now king). Plus, I loved the smith and the Morris dancers. The funniest, most intelligent fantasy series ever. If you haven’t read them, try them.

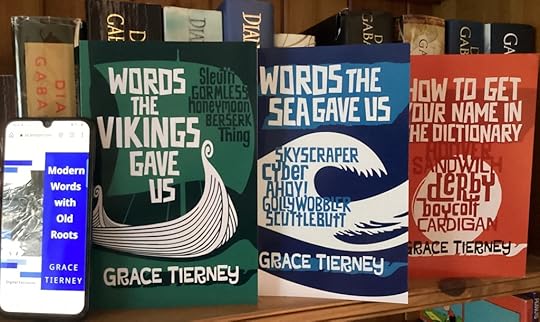

My four books inspired by this blog are out now in paperback and ebook (all the ways to get them are listed here). “Modern Words with Old Roots” delves into the astonishingly ancient history of 50 modern words from avatar to zarf. “Words the Vikings Gave Us” explores the influence of Old Norse and modern Scandinavia on English. “Words The Sea Gave Us” covers nautical words and phrases from ahoy to skyscraper. “How To Get Your Name In The Dictionary” records the lives of the people whose names became part of the English language including Guillotine, Casanova, and Fedora.

Right, that’s enough book chat. Next week I’ll be back with the history of unusual words. Wishing you happy reading in 2023.

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. this post contains affiliate links which make a small payment to the blog if you choose to purchase through them. #CommissionsEarned. Alternatively, you can use my digital tip jar to say thanks for this year’s words.

p.p.s. My fav books from 2021, 2020, 2019, and 2018 are also available.

December 12, 2022

The Alchemical Origins of Quintessential

Hello,

Although I’ve already covered most of my favourite words here on the blog, sometimes I’ll think “did I do that one?” and discover I somehow missed the history of a word I love. This morning I had that discovery with quintessential.

Quintessential is a way of describing something as being the most perfect example of its type. Your favourite tipple might be a quintessential glass of red wine, or your favourite James Bond actor might be quintessential casting. My homemade vanilla fudge which I only make for Christmas (because the ingredients aren’t exactly health food) is the quintessential festive feast in our house.

I was surprised to discover quintessential’s roots lie in alchemy.

Yes, alchemy, the medieval origins of modern chemistry but mostly obsessed with finding eternal life or turning lead into gold.

Quintessence arrived in English before quintessential. Let’s start there. It was used in the early 1400s in alchemy and philosophy as a literal term for the fifth essence. Quin means five here, as it does in quintuplet. It’s a borrowing from Latin’s quintus (fifth), via Old French. Essence followed the same route from essentia in Latin (being or essence) although in that case it came from an earlier Greek word ousia (essence) with a Proto Indo European root es (to be).

The Greeks had a hand in the concept of quintessence. They had a term pempte ousia (ether). Aristotle added the idea of ether to the four elements (water, earth, air, and fire). This fifth element was believed to be naturally bright, incorruptible, and moved in circles. It was a pure essence of all things and was the substance of heavenly bodies. Basically he believed quintessence was star dust. Alchemists immediately wanted to extract it and examine it.

The fifth element, the ether, and the quintessence are all the same thing and no, those alchemists didn’t turn lead into gold and they didn’t extract quintessence either.

The quintessential Wordfoolery

The quintessential WordfooleryBy the 1560s quintessence had acquired a second meaning – the pure essence of a situation or person. This came from the idea of extracting a small quantity of the essential virtues of something. It’s this meaning we use most today.

By the 1600s we’d added quintessential to the dictionary to describe this concept – the purest, the most refined, the very nature of quintessence – we’ve been using it ever since in a variety of ways which the alchemists would detest.

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

December 5, 2022

Taciturn and Tacit – quiet words

Hello,

This week’s word is taciturn. I’m surprised I haven’t delved into this one before as it was a favourite adjective of mine during my teens. For this I have to point the finger of blame firmly in the direction of the excellent adventure writer Alistair MacLean (1922-1987).

I frequently browsed second-hand bookshops and market stalls and his books were always on my mental “I want to get” list. He wrote some of the best war thrillers I’ve read, probably because he drew upon his own experiences in the Royal Navy in World War II. He sold more than 150 million copies but even if you’ve never read his books, you have probably watched the movies. “Guns of Navarone” and “Where Eagles Dare” were amongst the most famous.

His stories feature plenty of action and double-crossing plot twists. He nearly always has one character who is described as taciturn and usually one whose surname was Smith, Smythe, or Smithy. I loved the word taciturn the first time I read it and ended up christening one of the chairs in our kitchen Smithy in homage because, of course, chairs don’t talk very much. My parents thought I was insane.

If you say somebody is taciturn what you mean is that they are usually silent. Perhaps in our more noisy world there aren’t too many taciturn people left but I haven’t seen the word in any stories recently which is a shame.

“Grumpy Tiki” – a wood carving by my DH whose taciturn face adorns our garden

“Grumpy Tiki” – a wood carving by my DH whose taciturn face adorns our gardenTaciturnity was the way the word entered English. This is the quality of being taciturn and it arrived in the mid 1400s from Old French taciturnité and before that from Latin taciturnus (inclined to be silent) and tacitus (silent). The arrival of taciturn followed in the late 1700s from the same sources.

Tacitus in Latin also gives us some other words. By the 1600s we had tacit (silent or unspoken) as a way of describing something which is done without words, which is assumed e.g. tacit agreement. The Proto Indo European root of the Latin word is tak (to be silent) and gives us words about being silent, or being unable to speak in Gothic, Old Norse, Old Saxon, and Old High German.

Reticence, the avoidance of speaking too freely, or too much also arrived around 1600 via French and Latin, this time from reticere (keep silent) in Latin, but ultimately from the same roots.

Various ways of being quiet, but all from the same source. I think Smithy the Chair would approve of them all.

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. I finished my NaNoWriMo 2022 writing challenge by the way. My 14th win in a row. The first draft of “Words the Weather Gave Us” is incomplete but I made a sizable start on it. I’ll put it aside now while I work on other projects, but you’ll hear more about it later.

November 28, 2022

Dreaming of the Dog Days – Weather Words

Hello,

As I near completion of the first draft of “Words the Weather Gave Us” the weather has taken a turn for cold these days. The thermometer has dropped and heavier sweaters are looking tempting. As a result I’m dreaming of the Dog Days. Here’s an extract to let you know what I mean.

Local sunflower meadow in High Summer

Local sunflower meadow in High Summer{Extract from “Words the Weather Gave Us” by Grace Tierney copyright 2022}

Dog days are midsummer days of great warmth and we have the Romans to thank for the expression, with perhaps a little borrowing from the ancient Greeks.

The Romans called the hottest weeks of the summer caniculares dies. They believed that the Dog Star rising with the sun added to its heat and hence the dog days (3-11 July, although calculations vary depending on your location) suffered under their combined heat. Having been lucky enough to visit Rome during that time period, I can understand why the Romans espoused that theory. Thank goodness for all the wonderful old water fountains for refilling your bottle.

The Dog Star, Sirius, is the brightest star usually visible from Earth. It is so-named thanks to its position in the Big Dog constellation, also known as Alpha Canis Majoris. It should be dogs plural though as it’s a binary star, consisting of Sirius A and Sirius B.

The expression has been part of English since the 1500s. The date of Sirius rising with the sun has moved through the calendar over the centuries. In ancient Egypt, around 3,000 BC, it happened at the same time as the summer solstice, adding even more significance to its co-rising. At the time the solstice marked the start of their new year and the beginning of the crucial Nile flood season. It is likely that the association of Sirius with dogs began here as the star’s hieroglyph was a dog, but the exact reasons are lost in time.

{end of extract}

Until next time, happy reading, writing, and wordfooling,

Grace (@Wordfoolery)

p.s. It’s day 28 of the 30 days NaNoWriMo 2022 writing challenge and I’m edging up on the finish line. Wish me luck!

November 22, 2022

Modern Words with Old Roots

Hello,

For the last few years I’ve released a book for Christmas each year. This year, 2022, my plan was to release a book about Christmas. Real Life had other ideas. By August I recognised there was no way I could get “Words Christmas Gave Us” ready for release in time while also juggling the other balls in my life. Very reluctantly I set it aside for 2023.

Then I began to get “When’s the new book coming?” messages from readers and friends.

“Modern Words with Old Roots”, a new digital exclusive ebook released today, is my answer to those queries. It’s taken three months from start to finish because it’s shorter and I have skipped the paperback formatting, indexing, and cover steps. I hope you enjoy it and that it tides you over until “Words Christmas Gave Us” comes out in paperback, ebook, and hopefully hardback next year. Thank you for giving my first ever Wordfoolery “mini book” a try.

This time Wordfoolery takes a lighthearted look at the astonishingly ancient history of a hand-picked selection of 50 modern words from avatar to zarf.

It’s time to login (inspired by an actual piece of wood), open your kindle (inspired by Vikings), forget about the latest world crisis (thanks to an ancient Greek doctor), skip the doomscrolling (with a nod to William the Conqueror), and set off in hot pursuit (from the Age of Sail) of some juicy language fact hunting. You may be surprised by what you discover.

Ideal for word geeks, history buffs, and anybody who’s ever wondered about the roots of the latest trendy word in the dictionary.

“Modern Words with Old Roots” is out now on Kindle worldwide (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, and Amazon.de etc.) at the mini price of $0.99, £0.99, or €0.99 as an early Christmas gift from me.

As always, thanks to the wonderful community of readers who enrich the Wordfoolery blog with their passion for language.

Thank you for reading,

Grace (a.k.a. Wordfoolery)

Please note – This blog is an affiliate associate to Amazon US. I’m paid a small fee for any purchase you make through the Amazon links provided which helps support the running costs of the blog. Thank you.