Eric S. Raymond's Blog, page 4

January 31, 2020

Head-voice vs. quiet-mind

I’m utterly boggled. Yesterday, out of nowhere, I learned of a fundamental divide in how peoples’ mental lives work about which I had had no previous idea at all.

From this: Today I Learned That Not Everyone Has An Internal Monologue And It Has Ruined My Day.

My reaction to that title can be rendered in language as – “Wait. People actually have internal monologues? Those aren’t just a cheesy artistic convention used to concretize the welter of pre-verbal feelings and images and maps bubbling in peoples’ brains?”

Apparently not. I’m what I have now learned to call a quiet-mind. I don’t have an internal narrator constantly expressing my thinking in language; in shorthand. I’m not a head-voice person. So much not so that when I follow the usual convention of rendering quotes from my thinking as though they were spoken to myself, I always feel somewhat as though I’m lying, fabulating to my readers. It’s not like that at all! I justify doing that only because the full multiordinality of my actual thought-forms won’t fit through my typing fingers.

But, apparently, for others it often is like that. Yesterday I learned that the world is full of head-voice people who report that they don’t know what they’re thinking until the narratizer says it. Judging by the reaction to the article it seems us quiet-minds are a minority, one in five or fewer. And that completely messes with my head.

What’s the point? Why do you head-voice people need a narrator to tell you what your own mind is doing? I fully realize this question could be be reflected with “Why don’t you need one, Eric?” but it is quite disturbing in either direction.

So now I’m going to report some interesting detail. There are exactly two circumstances under which I have head-voice. One is when I’m writing or consciously framing spoken communication. Then, my compositional output does indeed manifest as narratizing head-voice. The other circumstances is the kind of hypnogogic experience I reported in Sometimes I hear voices.

Outside of those two circumstances, no head-voice. Instead, my thought forms are a jumble of words, images, and things like diagrams (a commenter on Instapundit spoke of “concept maps” and yeah, a lot of it is like that). To speak or write I have to down-sample this flood of pre-verbal stuff into language, a process I am not normally aware of except as an occasional vague and uneasy sense of how much I have thrown away.

(A friend reports Richard Feynman observing that ‘You don’t describe the shape of a camshaft to yourself.” No; you visualize a camshaft, then work with that visualization in your head. Well, if you can – some people can’t. I therefore dub the pre-verbal level “camshaft thinking.”)

To be fully aware of that pre-verbal, camshaft-thinking level I have to go into a meditative or hypnogogic state. Then I can observe that underneath my normal mental life is a vast roar of constant free associations, apparently random memory retrievals, and weird spurts of logic connecting things, only some of which passes filters to present to my conscious attention.

I don’t think much or any of this roar is language. What it probably is, is the shock-front described in the predictive-processing model of how the brain works – where the constant inrush of sense-data meets the brain’s attempt to fit it to prior predictive models.

So for me there are actually three levels: (1) the roaring flood of free association, which I normally don’t observe; (2) the filtered pre-verbal stream of consciousness, mostly camshaft thinking, that is my normal experience of self, and (3) narratized head-voice when I’m writing or thinking about what to say to other people.

I certainly do not head-voice when I program. No, that’s all camshaft thinking – concept maps of data structures, chains of logic. processing that is like mathematical reasoning though not identical to it. After the fact I can sometimes describe parts of this process in language, but it doesn’t happen in language.

Learning that other people mostly hang out at (3), with a constant internal monologue…this is to me unutterably bizarre. A day later I’m still having trouble actually believing it. But I’ve been talking with wife and friends, and the evidence is overwhelming that it’s true.

Language…it’s so small. And linear. Of course camshaft thinking is intrinsically limited by the capabilities of the brain and senses, but less so. So why do most people further limit themselves by being in head-voice thinking most of the time? What’s the advantage to this? Why are quiet-minds a minority?

I think the answers to these questions might be really important.

UPDARE: My friend, Jason Azze, found the Feynman quote. It’s from “It’s As Simple As One, Two, Three…” from the second book of anecdotes, What Do You Care What Other People Think?:

When I was a kid growing up in Far Rockaway, I had a friend named Bernie Walker. We both had “labs” at home, and we would do various “experiments.” One time, we were discussing something — we must have been eleven or twelve at the time — and I said, “But thinking is nothing but talking to yourself inside.”

“Oh yeah?” Bernie said. “Do you know the crazy shape of the crankshaft in a car?”

“Yeah, what of it?”

“Good. Now, tell me: how did you describe it when you were talking to yourself?”

So I learned from Bernie that thoughts can be visual as well as verbal.

January 26, 2020

Missing documentation and the reproduction problem

I recently took some criticism over the fact that reposurgeon has no documentation that is an easy introduction for beginners.

After contemplating the undeniable truth of this criticism for a while, I realized that I might have something useful to say about the process and problems of documentation in general – something I didn’t already bring out in How to write narrative documentation. If you haven’t read that yet, doing so before you read the rest of this mini-essay would be a good idea.

“Why doesn’t reposurgeon have easy introductory documentation” would normally have a simple answer: because the author, like all too many programmers, hates writing documentation, has never gotten very good at it, and will evade frantically when under pressure to try. But in my case none of that description is even slightly true. Like Donald Knuth, I consider writing good documentation an integral and enjoyable part of the art of software engineering. If you don’t learn to do it well you are short-changing not just your users but yourself.

So, with all that said, “Why doesn’t reposurgeon have easy introductory documentation” actually becomes a much more interesting question. I knew there was some good reason I’d never tried to write any, but until I read Elijah Newren’s critique I never bothered to analyze for the reason. He incidentally said something very useful by mentioning gdb (the GNU symbolic debugger), and that started me thinking, and now think I understand something general.

If you go looking for gdb intro documentation, you’ll find it’s also pretty terrible. Examples of a few basic commands is all they can do; you never get an entire worked example of using gdb to identify and fix a failure point. And why is this?

The gdb maintainers probably aren’t very self-aware about this, but I think at bottom it’s because the attempt would be futile. Yes, you could include a session capture of someone diagnosing and debugging a simple problem with gdb, but the reader couldn’t reliably reproduce it. How would you the user go about generating a binary on which the replicating the same commands produced the same results?

For an extremely opposite example, consider the documentation for an image editor such as GIMP. It can have excellent documentation precisely because including worked examples that the reader can easily understand and reproduce is almost trivial to arrange.

What’s my implicit premise here? This: High-quality introductory software documentation depends on worked examples that are understandable and reproducible. If your software’s problem domain features serious technical barriers to mounting and stuffing a gallery of reproducible examples, you have a problem that even great willingness and excellent writing skills can’t fix.

Of course my punchline is that reposurgeon has this problem, and arguably an even worse example of it than gdb’s. How would you make a worked example of a repository conversion that is both nontrivial and reproducible? What would that even look like?

In the gdb documentation, you could in theory write a buggy variant of “Hello, World!” with a crash due to null pointer dereference and walk the reader through locating it with gdb. It would be a ritual gesture in the right direction, but essentially useless because the example is too trivial. It would read as a pointless tease.

Similarly, the reposurgeon documentation could include a worked conversion example on a tiny synthetic repository and be no better off than before. In both problem domains reproducibility implies triviality!

Having identified the deep problem, I’d love to be able to say something revelatory and upbeat about how to solve it.

The obvious inversion would be something like this: to improve the quality of your introductory documentation, design your software so that user reproduction of instructive examples is as easy as its problem domain allows.

I understand that this only pushes the boundaries of the problem. It doesn’t tell you what to do when you’re in a problem domain as intrinsically hostile to reproduction of examples as gdb and reposurgeon are.

Unfortunately, at this point I am out of answers. Perhaps the regulars on my blog will come up with some interesting angle.

January 23, 2020

30 Days in the Hole

Yes, it’s been a month since I posted here. To be more precise, 30 Days in the Hole – I’ve been heads-down on a project with a deadline which I just barely met. and then preoccupied with cleanup from that effort.

The project was reposurgeon’s biggest conversion yet, the 280K-commit history of the Gnu Compiler Collection. As of Jan 11 it is officially lifted from Subversion to Git. The effort required to get that done was immense, and involved one hair-raising close call.

I was still debugging the Go translation of the code four months ago when the word came from the GCC team that they has a firm deadline of December 16 to choose between reposurgeon and a set of custom scripts written by a GCC hacker named Maxim Kyurkov. Which I took a look at – and promptly recoiled from in horror.

The problem wasn’t the work of Kyurkov himself; his scripts looked pretty sane to me, But they relied on git-svn, and that was very bad. It works adequately for live gatewaying to a Subversion repository, but if you use it for batch conversions it has any number of murky bugs including a tendency to badly screw up the location of branch joins.

The problem I was facing was that Kyurkov and the GCC guys, never having had their noses rubbed in these problems as I had, might be misled by git-svn’s surface plausibility into using it, and winding up with a subtly damaged conversion and increased friction costs for the rest of time. To head that off, I absolutely had to win on 16 Dec.

Which wasn’t going to be easy. My Subversion dump analyzer had problems of it own. I had persistent failures on some particularly weird cases in my test suite, and the analyzer itself was a hairball that tended to eat RAM at prodigious rates. Early on, it became apparent that the 128GB Great Beast II was actually too small for the job!

But a series of fortunate occurrences followed. One was that friend at Amazon was able to lend me access to a really superpowered cloud machine with 512GB. The second and much more important was in mid-October when a couple of occasional reposurgeon contributors, Julien “__FrnchFrgg__” Rivaud and Daniel Brooks showed up to help – Daniel having wangled his boss’s permission to go full-time on this until it was done. (His boss whose company is critically depended on GCC flourishing…)

Many, many hours of hard work followed – profiling, smashing out hidden O(n**2) loops that exploded on a repo this size, reducing working set, fixing analyzer bugs. I doubled my lifetime consumption of modafinil. And every time I scoped what was left to do I came up with the same answer: we would just barely make the deadline. Probably.

Until…until I had a moment of perspective after three week of futile attempts to patch the latest round of Subversion-dump analyzer bugs and realized that trying to patch-and-kludge my way around the last 5% of weird cases was probably not going to work. The code had become a rubble pile; I couldn’t change anything without breaking anything.

It looked like time to scrap everything downstream of the first-stage stream parser (the simplest part, and the only one I was completely sure was correct) and rebuild the analyzer from first principles using what I had learned from all the recent failures.

Of course the risk I was taking was that come deadline time the analyzer wouldn’t be 95% right but rather catastrophically broken – that there simply wouldn’t be time to get the cleaner code working and qualified. But after thinking about the odds a great deal, I swallowed hard and pulled the trigger on a rewrite.

I made the fateful decision on 29 Nov 2019 and as the Duke of Wellington famously said, “It was a damned near-run thing.” If I had waited even a week longer to pull that trigger, we would probably have failed.

Fortunately, what actually happened was this: I was able to factor the new analyzer into a series of passes, very much like code-analysis phases in a compiler. The number fluctuated, there ended up being 14 of them, but – and this is the key point – each pass was far simpler than the old code, and the relationships between then well-defined. Several intermediate state structures that had become more complication than help were scrapped.

Eventually Julien took over two of the trickier intermediate passes so I could concentrate on the worst of the bunch. Meanwhile, Daniel was unobtrusively finding ways to speed the code and slim its memory usage down. And – a few days before the deadline – the GCC project lead and a sidekick showed up on our project channel to work on improving the conversion recipe.

After that formally getting the nod to do the conversion was not a huge surprise. But there was a lot of cleanup, verification, and tuning to be done before the official repository cutover on Jan 11. What with one thing and another in was Jan 13 before I could declare victory and ship 4.0.

After which I promptly…collapsed. Having overworked myself, I picked up a cold. Normally for me this is no big deal; I sniffle and sneeze for a few days and it barely slows me down. Not this time – hacking cough, headaches, flu-like symptoms except with no fever at all, and even the occasional dizzy spell because the trouble spread to my left ear canal.

I’m getting better now. But I had planned to go to the big pro-Second Amendment demonstration in Richmond on Jan 20th and had to bail at the last minute because I was too sick to travel.

Anyway, the mission got done. GCC has a really high-quality Git repository now. And there will be a sequel to this – my first GCC compiler mod.

And posting at something like my usual frequency will resume. I have a couple of topics queued up.

December 23, 2019

The Great Inversion

There’s a political trend I have been privately thinking of as “the Great Inversion”. It has been visible since about the end of World War II in the U.S., Great Britain, and much of Western Europe, gradually gaining steam and going into high gear in the late 1970s.

The Great Inversion reached a kind of culmination in the British elections of 2019. That makes this a good time, and the British elections a good frame, for explaining the Great Inversion to an American audience. It’s a thing that is easier to see without the distraction of transient American political issues.

(And maybe I have an easier time seeing the pattern because I lived in Great Britain as a child. British politics is more intelligible to me than to most Americans because of that early experience.)

To understand the Great Inversion, we have to start by remembering what the Marxism of the pre-WWII Old Left was like — not ideologically, but sociologically. It was an ideology of, by, and for the working class.

Now it’s 2019 and the Marxist-rooted Labor party in Great Britain is smashed, possibly beyond repair. It didn’t just take its worst losses since 1935, it was eviscerated in its Northern industrial heartland, losing seats to the Tories in places that had been “safe Labor” for nigh on a century.

Exit polls made clear what had happened. The British working class, Labor’s historical constituency, voted anyone-but-Labor. Only in South Wales and a handful of English cities with large immigrant populations was it able to cling to power. In rural areas the rout was utter and complete.

To understand the why of this I think it’s important to look beyond personalities and current political issues. Yes, Jeremy Corbyn was a repulsive figure, and that played a significant role in Labor’s defeat; yes, Brexit upended British politics. But if we look at the demographics of who voted Labor, it is not difficult to discern larger and longer-term forces in play.

Who voted Labor? Recent immigrants. University students. Urban professionals. The wealthy and the near wealthy. People who make their living by slinging words and images, not wrenches or hammers. Other than recent immigrants, the Labor voting base is now predominantly elite.

This is the Great Inversion – in Great Britain, Marxist-derived Left politics has become the signature of the overclass even as the working class has abandoned it. Indeed, an increasingly important feature of Left politics in Britain is a visceral and loudly expressed loathing of the working class.

To today’s British leftist, the worst thing you can be is a “gammon”. The word literally means “ham”, but is metaphorically an older white male with a choleric complexion. A working-class white male, vulgar and uneducated – the term is never used to refer to men in upper socio-economic strata. And, of course, all gammons are presumed to be reactionary bigots; that’s the payload of the insult.

Catch any Labor talking head on video in the first days after the election and what you’d see is either tearful, disbelieving shock or a venomous rant about gammons and how racist, sexist, homophobic, and fascist they are. They haven’t recovered yet as I write, eleven days later.

Observe what has occurred: the working class are now reactionaries. New Labor is entirely composed of what an old Leninist would have called “the revolutionary vanguard” and their immigrant clients. Is it any wonder that some Laborites now speak openly of demographic replacement, of swamping the gammons with brown immigrants?

It would be entertaining to talk about the obvious parallels in American politics – British “gammons” map straight to American “deplorables”, of course, and I’m not even close to first in noticing how alike Donald Trump and Boris Johnson are – but I think it is more interesting to take a longer-term view and examine the causes of the Great Inversion in both countries.

It’s easy enough to locate its beginning – World War II. The war effort quickened the pace of innovation and industrialization in ways that are easy to miss the full significance of. In Great Britain, for example, wartime logistical demands – especially the demands of airfields – stimulated a large uptick in road-making. All that infrastructure outlasted the war and enabled a sharp drop in transport costs, with unanticipated consequences like making it inexpensive for hungry (and previously chronically malnourished!) working-class people in cities to buy meat and fresh produce.

Marxists themselves were perhaps the first to notice that the “proletariat” as their theory conceived it was vanishing, assimilated to the petty bourgeoisie by the postwar rise in living standards and the propagation of middlebrow culture through the then-new media of paperback books, radio, and television.

In the new environment, being “working class” became steadily less of a purchasing-power distinction and more one of culture, affiliation, and educational limits on upward mobility. A plumber might make more than an advertising copywriter per hour, but the copywriter could reasonably hope to run his own ad agency – or at least a corporate marketing department – some day. The plumber remained “working class” because, lacking his A-level, he could never hope to join the managerial elite.

At the same time, state socialism was becoming increasingly appealing to the managerial and upper classes because it offered the prospect not of revolution but of a managed economy that would freeze power relationships into a shape they were familiar with and knew how to manipulate. This came to be seen as greatly preferable to the chaotic dynamism of unrestrained free markets – and to upper-SES people who every year feared falling into poverty less but losing relative status more, it really was preferable.

In Great Britain, the formation of the National Health Service in 1947 was therefore not a radical move but a conservative one. It was a triumph not of revolutionary working-class fervor overthrowing elites but of managerial statism cementing elite power in place.

During the long recovery boom after World War II – until the early 1970s – it was possible to avoid noticing that the interests of the managerial elite and the working classes were diverging. Both the U.S. and Great Britain used their unmatched industrial capacity to act as price-takers in international markets, delivering profits fat enough to both buoy up working-class wages and blur the purchasing-power line between the upper-level managerial class and the owners of large capital concentrations almost out of existence.

The largest divergence was that the managerial elite, like capitalists before them, became de-localized and international. What mobility of money had done for the owners of capital by the end of the 19th century, mobility of skills did for the managerial class towards the end of the 20th.

As late as the 1960s, when I had an international childhood because my father was one of the few exceptions, the ability of capital owners to chase low labor costs was limited by the unwillingness of their hired managers to live and work outside their home countries.

The year my family returned to the U.S. for good – 1971 – was about the time the long post-war boom ended. The U.S. and Great Britain, exposed to competition (especially from a re-industrialized Germany and Japan) began a period of relative decline.

But while working-class wage gains were increasingly smothered, the managerial elite actually increased its to price-take in international markets after the boom. They became less and less tied to their home countries and communities – more willing and able to offshore not just themselves but working-class jobs as well. As that barrier eroded, the great hollowing out of the British industrial North and the American Rust Belt began.

The working class increasingly found itself trapped in dying towns. Where it wasn’t, credentialism often proved an equally effective barrier to upward mobility. My wife bootstrapped herself out of a hardscrabble working-class background after 1975 to become a partner at a law firm, but the way she did it would be unavailable to anyone outside the 1 in 100 of her peers at or above the IQ required to earn a graduate degree. She didn’t need that IQ to be a lawyer; she needed it to get the sheepskin that said she was allowed to be a lawyer.

The increasingly internationalized managerial-statist tribe traded increasingly in such permissions – both in getting them and in denying them to others. My older readers might be able to remember, just barely, when what medical treatment you could get was between you and your physician and didn’t depend on the gatekeeping of a faceless monitor at an insurance company.

Eventually, processing of those medical-insurance claims was largely outsourced to India. The whole tier of clerical jobs that had once been the least demanding white-collar work came under pressure from outsourcing and automation. effectively disappearing. This made the gap between working-class jobs and the lowest tier of the managerial elite more difficult to cross.

In this and other ways, the internationalized managerial elite grew more and more unlike a working class for which both economic and social life remained stubbornly local. Like every other ruling elite, as that distance increased it developed a correspondingly increasing demand for an ideology that justified that distinction and legitimized its power. And in the post-class-warfare mutations of Marxism, it found one.

Again, historical contingencies make this process easier to follow in Great Britain than its analog in the U.S. was. But first we need to review primordial Marxism and its mutations.

By “primordial Marxism” I mean Marx’s original theory of immiseration and class warfare. Marx believed, and taught, that increasing exploitation of the proletariat would immiserate it, building up a counterpressure of rage that would bring on socialist revolution in a process as automatic as a steam engine.

Inconveniently, the only place this ever actually happened was in a Communist country – Poland – in 1981. I’m not going to get into the complicated historiography of how the Soviet Revolution itself failed to fit the causal sequence Marx expected; consult any decent history. What’s interesting for our purposes is that capitalism accidentally solved the immiseration problem well before then, by abolishing Marx’s proletariat through rising standards of living – reverse immiseration.

The most forward-thinking Marxists had already figured out this was going to be a problem by around 1910. This began a century-long struggle to find a theoretical basis for socialism decoupled from Marxian class analysis.

Early, on, Lenin developed the theory of the revolutionary vanguard. In this telling, the proletariat was incapable of spontaneously respond to immiseration with socialist revolution but needed to be led to it by a vanguard of intellectuals and men of action which would, naturally, take a leading role in crafting the post-revolutionary paradise.

Only a few years later came one of the most virulent discoveries in this quest – Fascism. It is not simplifying much to say that Communists invented Fascism as an escape from the failure of class-warfare theory, then had to both fight their malignant offspring to death and gaslight everyone else into thinking that the second word in “National Socialism” meant anything but what it said.

During its short lifetime, Fascism did exert quite a fascination on the emerging managerial elite. Before WWII much of that elite viewed Mussolini and Hitler as super-managers who Got Things Done, models to be emulated rather than blood-soaked tyrants. But Fascism’s appeal did not long survive its defeat.

Marxists had more success through replacing the Marxian economic class hierarchy with other ontologies of power in which some victim group could be substituted for the vanished proletariat and plugged into the same drama of immiseration leading to inevitable revolution.

Most importantly, each of these mutations offered the international managerial elite a privileged role as the vanguard of the new revolution – a way to justify its supremacy and its embrace of managerial state socialism. This is how you get the Great Inversion – Marxists in the middle and upper classes, anti-Marxists in the working class being dismissed as gammons and deplorables.

Leaving out some failed experiments, we can distinguish three major categories of substitution. One, “world systems theory”, is no longer of more than historical interest. In this story, the role of the proletariat is taken by oppressed Third-World nations being raped of resources by capitalist oppressors.

Though world systems theory still gets some worship in academia, it succumbed to the inconvenient fact that the areas of the Third World most penetrated by capitalist “exploitation” tended to be those where living standards rose the fastest. The few really serious hellholes left are places (like, e,g. the Congo) where capitalism has been thwarted or co-opted by local bandits. But in general, Frantz Fanon’s wretched of the Earth are now being bourgeoisified as fast as the old proletariat was during and after WWII.

The other two mutations of Marxian vanguard theory were much more successful. One replaced the Marxian class hierarchy with a racialized hierarchy of victim groups. The other simply replaced “the proletariat” with “the environment”.

And now you know everything you need to understand who the Labor party of 2019 is and why it got utterly shellacked by actual labor. If you think back a bit, you can even understand Tony Blair.

For Tony Blair it was who first understood that the Labor Party’s natural future was as an organ not of the working class, but as a fully converged tool of the international managerial elite. Of those who think their justifying duty is to fight racism or sexism or cis-normativity or global warming and keep those ugly gammons firmly under their thumbs, rather than acting on the interests and the loudly expressed will of the British people.

Now you also know why in the Britain of 2019, the rhetoric of Marxism and state socialism issues not from assembly-line workers and plumbers and bricklayers, but from the chattering classes – university students, journalists and pundits, professional political activist, and the like.

This is the face of the Great Inversion – and its application to the politics of the U.S. is left as a very easy exercise.

November 19, 2019

Beware the finger trap!

I think it’s useful to coin pithy terms for phenomena that all software engineers experience but have a name to put to. Our term of the day is “finger trap”.

<!--more>

A finger trap is a programming problem that is conceptually very simple to state, and algorithmically fairly trivial, but an unreasonable pain in the ass to actually code given that simplicity.

It's named after a gag called the <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese... Finger Trap</a>, simple, deceptive, and the harder you struggle with it the more trouble you have extricating yourself.

My favorite very simple example of a finger trap is interpreting <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escape_... backslash escapes.</a> The trap closes when you realize you have to interpret \\, \\\, \\\\, and so forth.

A very famous finger trap is BitBlt - copy a source rectangle of pixels to a target location. The tricky part comes from the background having edges; you may have to clip the copy region to avoid trying to copy pixels that are off the edge of the world, and then modify the copy so you only copy to locations in the world.

These two examples exemplify what I think is the most common kind of fingertrappage: when it's easy to miss edge cases, and as you get deeper in the edge cases proliferate. In the case of BitBLT these are both figurative and <em>literal</em> edge cases!

When I bounced this term off some friends I learned that Amazon uses finger traps to screen potential developer hires. A finger trap, you see, is a test both of coding skill and personality. How good are you at anticipating edge cases? How do you react when you discover there are edge cases you didn't expect?

Do you plow on stolidly, spot-gluing a series of increasingly dubious kludges to your original naive approach? Do you panic and recover only with difficulty, if at all? Or do you step back and rethink the problem, sitting on your coding fingers until you have mapped out the edge cases in your head to at least one level deeper than before?

A Chinese finger trap gets its grip on people because, having gotten themselves in a little bit of trouble, they do an instinctive but wrong thing, and then repeat the failing behavior as though doing it harder will get them out of trouble.

Software finger traps catch developers in a very similar way. To get out of one, relax, rethink, and reframe.

The good news, if you're a junior or intermediate-level developer, is that once you've seen enough finger traps you'll start to be able to detect them before they close on you. In which case you can move straight to the winning part of the game, which is <em>developing a clear mental model of the edge cases before you write more code.</em>

You will not always succeed at this the first time. Serious finger traps have multiple layers, and spiky bits where you're least expecting them. The point is, when you hit a finger trap, you have to relax and think your way out. Trying to code your way out will only get you more stuck.

My commenters are invited to suggest other examples of finger traps.

</p>

November 17, 2019

Some places I won’t go

A few minutes ago I received a request by email from a conference organizer who wants me to speak at an event in a foreign country. Unfortunately, the particular country has become a place I won’t go.

Having decided that I want my policy and my reasoning to be publicly known, I reproduce here the request and my reply. I withhold the requester’s name for his protection.

Hi, Mr Raymond. I am Free Software promoter and I always try to create new events of this topic.

Few days ago I readed “How to become a hacker”: Congratulations… I like it very much. Your excellent file and your interview in Revolution OS make me decide to write a mail for you to know your opinion about a visit (of you) to Venezuela.

Would you like to visit us the next year? Every year, in april, the community of my city organize a event, but there are many time to create a plan to guarantee your visit to Venezuela. If you could come only in another month, there will be not problem. I am sure that my partners would be happy to work to mak posible your visit.

If there is any possibility to invite you to our country, it would be fantastic… I guess that your visit would be a great support to the movement. I will be waiting your answer. Thanks for to read this mail.

Best regards.

Thanks for the invitation. I have good memories of Venezuela; I lived there as a child for four years. When I revisited in 1998 I was told that my fragmentary Spanish still carries a Venezuelan accent. In better circumstances I would be happy to travel there again.

Unfortunately I must decline. I will not go where a communist or socialist regime holds power. I have refused several invitations to mainland China for the same reason. You can ask me again when Maduro is deposed, the Chavistas are broken, and the Cuban Communist “advisors” running the apparatus of repression have been deported or (better) shot like rabid dogs.

Until then, I don’t think I’d be safe in Venezuela. And even if I did not have that concern, I refuse to give a socialist/communist government even the tiny, tacit bit of support my visit would confer.

Good luck taking back your country.

November 10, 2019

Grasping Bloomberg’s nettle

Michel Bloomberg, the former Mayor of New York perhaps best known for taking fizzy drinks, and now a Democratic presidential aspirant, has just caused a bit of a kerfuffle by suggesting that minorities be disarmed to keep them alive.

I think the real problem with Bloomberg’s remark is not that it reads as shockingly racist, it’s that reading it that way leaves us unable to deal with the truth he is telling. Because he’s right; close to 95% of all gun murders are committed by minority males between 15 and 25, and most of the victims are minorities themselves. That is a fact. What should we do with it?

It’s the 21st century and pretty much everybody outside of a handful of sociopaths and Affirmative Action fans has a moral sense that it’s wrong to make laws that discriminate on the basis of skin color. On the other hand, Bloomberg is broadly correct about the effect of disarming minorities, if it could actually be accomplished. (He might be optimistic by 5% or so, according to my knowledge of the relevant facts, and disarming minorities is effectively impossible, but neither of these objections are relevant to where I’m going with this.)

I think it is quite unlikely that Bloomberg has classically racist intentions in what he said. Sure, it’s fun in an Alinskyite sort of make-them-live-up-to-their-own-rules way to pillory a lefty like Bloomberg over this sort of remark, but let’s get real. This is not a man with a particular desire to oppress black or brown people. What’s obnoxious about Nanny Bloomberg is that he thinks he has the moral standing to oppress anybody in the name of whatever cause du jour currently exercises him.

So once we’ve stopped flogging the (rather risible) idea that Bloomberg is a racist, where are we? How do we use the statistical truth he pointed out without being racist ourselves?

There’s nothing magic about the amount of melanin in somebody’s skin that makes them so much more more likely to be a violent criminal that Bloomberg’s 95% figure is almost true. Dark skin can’t be the problem here; it has to be something else that is correlated with dark skin, predicted by it, but not it.

I don’t think there’s any mystery about what that is. Criminals are, by and large, stupid. American blacks have an average IQ of 85. Hispanics average 88. People with low IQs are bad at forward planning; this makes them impulsive and difficult to defer with negative consequences. It’s a safe bet that black and Hispanic criminals are, like white criminals, largely drawn from the subnormal end of their populations’ IQ bell curves.

If Bloomberg had said “We ought to disarm everyone with an IQ of 85 or below”, he would actually be more statistically correct than he was. That would still be pretty near impossible. But it wouldn’t be racist.

September 28, 2019

The dream is real

So, I just listened to an elaborate economic and engineering rationale for why Elon Musk’s new Starship is not the tall skinny pressurized-aluminum cylinder we’re used to thinking of a real rocket, but a fat cigar-shaped thing made of stainless steel, with tail fins.

And I don’t believe a word of it.

It had to be that way because Elon Musk grew up on the same Golden Age science fiction magazine cover illustrations I did, and it looks exactly like those.

Has tailfins. Freaking tailfins. And lands on a pillar of fire just like God and Robert Heinlein (PBUH) intended.

The dream is real.

September 14, 2019

Gratitude for Beto

Beto O’Rourke is a pretty risible character even among the clown show that is the 2020 cycle’s Democratic candidate-aspirants. A faux-populist with a history of burglary and DUI, he married the heiress of a billionaire and money-bombed his way to a seat in the House of Representatives, only to fail when he ran for the Senate six years later because Texas had had enough of his bullshit. Beneath the boyish good looks on which he trades so heavily, his track record reveals him to be a rather dimwitted and ineffectual manchild with a severe case of Dunning-Kruger effect.

Beto’s Presidential aspirations are doomed, though he and the uncontacted aborigines of the Andaman Islands are possibly the only inhabitants of planet Earth who do not yet grasp this. Before flaming out of the 2020 race to a life of well-deserved obscurity, however, Beto has done the American polity one great service for which I must express my most sincere and enduring gratitude.

In September 12th, 2019, at third televised debate among the Democratic aspirants, Beto O.Rourke said “Hell, yes, we’re going to take your AR-15”. And nobody on stage demurred, then or afterwards. And the audience applauded thunderously.

At a stroke, Beto irrecoverably destroyed a critical part of the smokescreen gun-control advocates have been laying over their intentions since the 1960s. He put gun confiscation with the threat of door-to-door enforcement by violence on the table, and nobody in the Democratic Party auditorium backed away.

It’s that last clause that is really telling. Beto’s own intentions will soon cease to be of interest to anyone but specialist historians. What matters is how he has made “Nobody is coming to take your guns” a disclaimer that no Democrat – and, extension, any advocate of soi-disant “common-sense” firearms restrictions – can ever hide behind again.

His talk of “military weapons” was, of course, obfuscatory bullshit. The AR-15 is a civilianized rifle the lacks exactly the capability to fire full auto or bursts that is essential for a battlefield weapon. Over ten million AR-15-pattern variants are in civilian hands; it’s the single most popular sport and hunting rifle in the U.S. or for that matter the entire world.

Every single AR-15 owner is on notice. The Democratic presidential candidates and their audience are down with the concept of LEOs raiding your home and forcibly confiscating your guns, even if you’re a model citizen with no criminal record or red flags. The fact that you, your family, or your pets get shot dead through malice or incompetence does not really signify to them. Got to break a few eggs to make that omelette, comrade!

Hell, if you happen to be white or male today’s Democrats might consider it – what’s the currently fashionable phrase? – “redistributive justice”. No worries though; there are statistical reasons to expect that blacks and Hispanics will be over-represented in the actual body count.

This is horrible – it’s a nightmare and a bad sign for our republic that advocating police-state behavior like this doesn’t get politicians driven from public life – but it’s also very clarifying.

Consider registration and licensing laws, background checks, and other requirements that allow the government to identify and target gun owners. Our civil-rights advocates have been saying for decades that these were intolerable because they have the corrupt purpose of enabling future confiscations. In response, we’ve been treated to endless condescending repetitions of “Nobody is coming to take your guns”.

We knew that was a lie, that forcible confiscation was always the endgame once lesser restrictions had shifted the Overton Window far enough, but way too many people outside the gun culture were fooled. The great service Beto O’Rourke has done is that the pretense will now be very much more difficult, and perhaps entirely impossible.

Thank you, Robert Francis “Beto” O’Rourke. You did not intend it, but you have provided a teachable moment for which everyone who takes the Second Amendment seriously should be grateful.

EDIT: Now lightly altered to reflect that at least one Democratic legislator has demurred. Senator Chris Coons said he disagreed with Beto: “We need to focus on what we can get done.” This of course is code for “You idiot! You let the mask slip! We need to continue with the slow strangulation!”

September 4, 2019

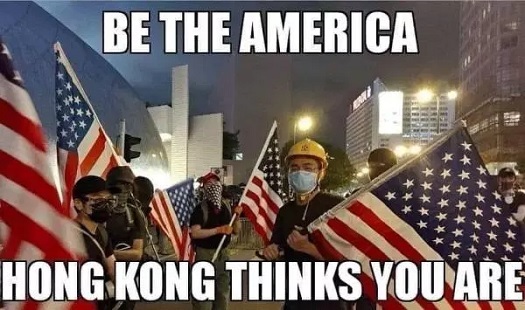

Be the America Hong Kong thinks you are

I think this is my favorite Internet meme ever.

Yeah, Hong Kong, we actually have a problem with Communist oppression here, too. Notably in our universities, but metastatizing through pop culture and social media censorship too. They haven’t totally captured the machinery of state yet, but they’re working on that Long March all too effectively.

And you are absolutely right when you say you need a Second-Amendment-equivalent civil rights guarantee. Our Communists hate that liberty as much as yours do – actually, noticing who is gung-ho for gun confiscation is one of the more reliable ways to unmask Communist tools.

We need to be the America you think we are, too. Some of us are still trying.

Eric S. Raymond's Blog

- Eric S. Raymond's profile

- 141 followers