Armand D’Angour's Blog, page 2

March 23, 2017

The Codes of Horace

[An abbreviated version of a talk I gave to the Horatian Society in London in 2005, in which I take a critical view of the idea that poets and authors insert acrostic or other ‘codes’ into their works.]

The profanum vulgus, the lay public spurned by our poet in Odes 3.1, has latched on to codes with a passion. Not so long ago a book called The Bible Code purported to show that recherché patterns of letters in the Hebrew text of the Bible can be shown to produce strings of miraculous predictions. No doubt the Bible code will have predicted that half the world would fall for the heady fictions expounded by Dan Brown in The Da Vinci Code. Sadly, the clues that might lead us to the truth about Horace cannot be unravelled as simply and definitively as the truth of the Holy Grail. Horace is a poet of many codes as well as many Odes, so I should not be satisfied to speak simply of the Horace Code.

Pindarum quisquis studet aemulari, Horace warns Iullus Antonius in Odes 4.2 – ‘whoever strives to emulate Pindar’ risks the watery death suffered by Icarus after he flew too close to the sun with wings of wax. Commentators on this ode discuss the meaning of aemulari – is it rivalry or imitation? – the significance Icarus’ borrowed wings in that context, the poetic and social status of the addressee Iullus Antonius, and so on. These are what I would call genuine Horatian codes – verbal, poetic, and historical puzzles – that demand our attention if we are to appreciate Horace’s poetry. But one cryptic fact I recently discovered in a commentary was that in lines 1 and 3 the words Pindarum and daturus contain the syllables PIN DA and RUS, while the words nomina ponto in line 4 contain an anagram of the addressee’s name, Antoni, in the vocative. How clever, one instantly thinks – but the thought is rapidly superseded by a question: why on earth Horace would want to encode these names so ingeniously into a poem, indeed a stanza, which actually contains the names of both Pindar and Iullus? One may equally well observe, as I subsequently did, that the initial letters of each line in the opening stanza spell P-I-N-N, while the final letters of the last couplet are I-S: pinnis, wings, the very things Horace has told us the Pindaric emulator depends upon, nititur! A nice coincidence, perhaps, but hardly a coded message.

In his well-known book on Horace, the scholar Eduard Fraenkel declared that the odes are ‘self-contained works of art’ and not ‘written for only a few initiates’. He deplored what he called the ‘destructive tendency…to treat any ancient poem as a kind of riddle, the solution of which should be the primary concern of the commentator’. Horace, he thundered, ‘does not play hide-and-seek with the general reader’, a pronouncement curiously reminiscent of Einstein’s comment on Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle – ‘God does not play dice’. I only agree up to a point. After all, Horace’s forthright statement in Odes 3.1 odi profanum vulgus et arceo could almost be translated ‘I don’t care for the general reader, so I play hide and seek with him’! Just as nowadays physicists generally accept that God does play dice, Fraenkel was presuming too much to claim he knew the mind of Horace. Horace’s poems are replete with riddling allusions, covert patterns, and subtle wordplay; and in general they present ambiguous and complex messages which are bound to challenge the reader to unravel their meaning. Riddler or not, Horace has always presented an enigmatic and indeterminate persona, hidden behind great poetry that requires us to try to decode his personality, beliefs and poetic intentions through close scrutiny of his individual words and artful phrases. Is he modest or disingenuous, a moralist or a libertine, Augustus’ supporter or lackey, Apollonian or Dionysiac, a prophet or a craftsman?

In warning against Pindaric emulation in Odes 4.2, Horace compares his own activity to that of a busy Italian bee, apis Matinus. In the Ars Poetica he indicates exactly how laborious his mode of work is likely to have been. There he advises the poet not to be satisfied with his finished product until, like a sculptor, he has whittled and chiselled away all imperfections and refined it a dozen times until it is shaped to a nicety. The words Horace uses for ‘to a nicety’ are ‘ad unguem’, literally ‘to a fingernail’. Why did the phrase come to have this meaning, and what would Horace have expected his readers to understand by it? Commentators have referred the phrase to a passage in the satirist Persius in which a sculptor in marble is described running his fingernail over a finished statue to test that its surface is perfectly smooth. But Persius was writing a whole century after Horace, and there’s no indication that the simple phrase ad unguem should evoke such an image in the Ars Poetica. If Horace’s words are to be referred to anything, it has to be to a pre-existing use of such a phrase; and there’s only one such to be found, the use of ‘to a nail’ in Greek, eis onucha, a phrase used by the fifth-century BC sculptor Polyclitus of Argos in his lost treatise on sculpture.

The fragment of Polyclitus actually says that ‘the hardest part of creating a sculpture is when the clay is worked eis onucha, into the nail’. What does this mean? Art historians have no doubt. The process of making a statue out of bronze involved constructing a core figure out of wood and clay, covering it with a layer of thick wax, carving all the fine details such as hair and fingernails into the wax, and then placing a further clay mantle over that. The clay would be baked solid, and molten bronze would be poured into the space between the two layers of clay, melting the wax and solidifying into the finely etched moulds on the inner surface of the clay mantle. In order to achieve the extraordinary precision of detail that we can still see on such magnificent works as the Riace Bronzes, the sculptor had to take special care when applying the final layer of clay to the small details etched into the wax covering. That was why the hardest part was working the clay into the fingernails or toenails – Greek onyx and Latin unguis can mean either – of the pre-sculpted figure: because they represented the tiniest and most intricate elements of the resulting statue. So when Horace tells his aspiring poet to whittle down his work ad unguem, he’s not referring at all to the artist’s fingernail, as commentators have supposed since antiquity, but to the smallest detail, the unguis, of the finished figure.

Ad unguem is an example of the kind of Horatian code that isn’t meant to pose a riddle but nonetheless requires careful decoding. One of the pleasures of doing so is that it demonstrates the compressed artistry of Horatian phraseology, showing how steeped Horace was in Greek culture and literature. Other clues similarly embedded in his poems can be, and are regularly, referred to Greek precedents and predecessors. Most of the women’s names, for instance, found in his Odes are Greek, pointing us in the direction of Greek lyric verse rather than to the Hellenised demi-monde of Horace’s contemporary Rome. Horace will frequently suggest a pun on their names, such as in Odes 1.33, where Glycera, whose name in Greek means ‘sweet’, is described as immitis, ‘harsh’. He does the same with Roman addressees, as with Grosphus in Odes 2.16, whose name means ‘javelin’ in Greek. ‘Quid brevi fortes iaculamur aevo / multa?’ Horace asks mischievously, literally translated by David West ‘Why do we brave fellows throw so many javelins in our short lives?’ In Odes 3.17 the bogus claims of Aelius Lamia to noble lineage are gently mocked by Horace’s knowledge that Lamia is the Greek for ‘bogeyman’.

So what about Horace’s own name? The American scholar Kenneth Reckford has argued that Horace intended us to relate his name to the Latin hora, hour or season, and it’s true that Horace makes frequent reference to the passing of time and to seasons. But to my ears, and I think to Roman ones, hora with its long first syllable wouldn’t really echo Horatius with its short one. Moreover, Horace names himself only once in the Odes, at the very end of Odes 4.6, where the words ‘vatis Horati’ – Horace the seer – seem significantly juxtaposed. The image of the vates, the inspired bard, is made concrete in Odes 2.19 which begins ‘I have seen Bacchus among the lonely crags, teaching his songs,’ Bacchum in remotis carmina rupibus / vidi docentem. This suggests another possibility. When Horace was completing his education in Athens, it must have occurred to him that the vocative of his name, ‘Horati’, sounded exactly like the Greek words hora ti – ‘see something!’. Coincidence? It seems no less likely than similar codes that have been proposed in all seriousness. I really cannot believe the first word of Odes Book 3, Odi (I spurn) is a self-referential pun on the Greek ôdoi, ‘songs’ or Odes, possibly picking up odi in the last Ode of Book 1, Persicos odi. Are we even supposed to construe Persicos odi as per sic os Odi – ‘thus through my mouth come Odes’? In the face of such absurdities one can only exclaim ‘Ye gods’ – which, by the way, translates into Latin as (you got it) O di!

Horace certainly indicates his own emulation of Pindar, by signs both overt and covert. Even in Odes 4.2, Horace can hardly suggest without irony that one should avoid imitating Pindar and then call himself a bee, since he knew that Pindar himself in his 10th Pythian Ode represented himself as a bee. Horace intends us to think of him as in some way attaining Pindaric status, and an association to Pindar’s poetry is surely coded into the last couplet of Odes book 3, where we read of the Delphic laurels awarded to victorious athletes. Horace suggests with true Pindaric boastfulness that he be crowned poet laureate, and just as the last word of Pindar’s Olympian odes is chaitan, hair, the last word of Horace’s first collection of Odes is comam, hair. David West ends his collection of recent commentaries on Horace’s Odes with this observation, so inevitably the last word of his commentary on Odes 3 is also ‘hair’. No coincidence, of course. Professor West is clearly making a claim to his affinity with Pindar and Horace. But what about the very first Ode, in which the first example Horace gives of the way of life, mos, sought by the ambitious is that of an Olympic charioteer, the kind of individual famously praised by Pindar in his Victory Odes? Horace ends Odes 1.1 with the suggestion that his own chosen way of life, mos, indeed his destiny, sors, is to be the star of the Roman lyric firmament. So should we not look for a code that reinforces his theme? Well, the initial letters of the first three lines of Odes 1.1 spell M-O-S, mos, while the final letters of lines 24-7 spell S-O-R-S.

Quo Musa tendis? Returning to my original proposal to emulate Dan Brown, let me accelerate into ‘Brownian motion’, a term descriptive, appropriately enough, of gas, and in particular of the way its particles move with chaotic randomness when heated up. It seems that a code exists which proves that Horace did not after all, as has long been supposed, die a childless bachelor. Hitherto one would have scorned the notion that the ‘puer’ addressed in Odes 1.38 and 3.14 could refer to Horace’s own son. Now, thanks to Dan Brown’s alter ego Dan Gore, we know better. In fact, I can now reveal the sensational truth that our poet left a bloodline whose secret has been jealously guarded for centuries by a society of self-selected initiates who gather annually in a venerable edifice in the heart of this great metropolis. But rather than indulging in more cryptological onomastic libertinism, let me give the last word to Horace: ‘I shall not wholly die; a large part of me will escape the final reckoning’ – non omnis moriar, multaque pars mei / vitabit Libitinam (Odes 3.30.6-7).

February 27, 2017

Flights of ancient fancy

Flying in the Ancient World

As published in Omnibus (first delivered at a Classical Association Conference on 1st April 1999).

Already in the 5th century BC, flying was in the air...

The subject of ancient aeronautics has, surprisingly, been largely neglected by ancient historians. We know that ancient engineers developed impressive technologies for building, water-carrying, naval and military purposes, which required a practical understanding of natural forces and how to exert control over them. Greek and Lain texts provide a lot of information about ancient ideas on techniques and principles of flight. Although it is commonly supposed that all ancient accounts of flight are no more than fantasy, at various periods the Greeks and Romans were clearly preoccupied with turning that fantasy into reality. However, travel by air or sea would have presented a perilous prospect: ‘caelum ipsum petimus stultitia’, laments Horace (Odes 1.3.38) ‘in our folly we head for the sky itself’. Nevertheless, intrepid explorers and adventurers regularly braved long ocean voyages. Others, it seems, persisted in investigating the possibility of flight.

Descriptions of flying in ancient literature refer predominantly to birds or to gods. In Homer and Virgil, winged deities and spirits throng the flight-paths of the ancient Mediterranean. Flying inspired a host of metaphors, like Homer’s ‘winged words’, and ‘wings of song’. Metaphors of poetic flight evoked literal images of ocean and earth – images grounded in the poets’ actual experiences. The importance of keeping in mind the physical reality of Greece was stressed by the one time Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, E.R. Dodds, who asked: ‘How shall [we] enter into the concrete experience of Greek culture, material or literary, with no experience of the soil and landscape that gave it birth?’ The vista of land and sea, apparently so near and yet so far, is familiar to anyone who ascends Mt. Etna or Parnassus, and might offer a strong inducement at least to dream of taking wing. Frequent and often detailed depictions of flight in ancient art and literature tell us how ancient aviators sought to turn that dream into reality.

The history of aviation proper begins with the attempt by the father-and-son team, Daidalos and Ikaros, to fly from Crete to Sicily. The story of their flight was widely told in antiquity. What underlies the legend? The Cretan Daidalos represents a figure of craftsman or inventor. As in the case of ‘Homer’, Daidalos came to represent a series of specialist practitioners over many centuries, inspired by contact with the Near East. Their accomplishments elicited reactions of wonder and admiration, and the name ‘Daidalos’ was specifically attached to feats of technical wizardry. So, in the Greek imagination, the palace at Knossos became the labyrinth designed by Daidalos; the Minotaur was the offspring of an artificial bull made by him; and an oft-repeated theme told of statues coming alive and walking, so lifelike were the figures of human beings sculpted by him.

Daidalos was famed above all for the wings he fashioned from feathers and wax for himself and Ikaros in their bid to fly from Crete. The Cretan connection gives us a clue to the historical background. It was the Cretans who, as early as the 2nd millenium B.C., took the lead in adopting sail technology from the Egyptians, and according to Thucydides (1.8), Minos of Crete was the first man to establish a maritime empire. Daidalos’s wife was named Naukrate, ‘mistress of the sea’, and the invention of the sail was attributed to Daidalos himself (Paus. 9.11.2-3). The harnessing of wind-power for purposes of sea travel was clearly a genuine technological breakthrough, and it was only a matter of time before the principle of sail-power was applied to air travel. A vase-painting from the 6th century B.C. captures Daidalos en route to Sicily – a destination with recurring significance for ancient aeronautics. Daidalos’ flight fired the imagination of aviators ancient and modern, but his successful design of wings eluded future generations despite detailed attempts at reconstruction, such as on the Roman panel of the 2nd century A.D. from Villa Albani and in Ovid’s famous description (Met.8. 189 f.):

He laid the feathers in a row, beginning with the smallest, short following long to form a curve…Then he tied them middle and bottom with string and wax, and, so fastened, he arched them slightly to imitate real birds’ wings…When the finishing touches had been put on his work, the craftsman himself balanced his body between the two wings and hung poised, beating the air.

The fate of Ikaros, who fell into the sea and drowned, was bound to dampen enthusiasm for such high enterprise. But in the 5th century B.C., a surge of interest in human inventiveness led to a renewed study of aeronautics, which is reflected in the way flight it a dominant theme for Athenian playwrights. Daidalos himself featured in satyr-plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles and was the central character in plays by Aristophanes and Euripides. Flying was in the air…But the fate of Ikaros was also a warning of the dangers of human beings failing to keep their feet on the ground: ‘cleverness’, warns a Euripidean chorus, ‘is not wisdom’.

Aristophanes enjoyed poking fun at scientists and inventors, and those who tried to fly were ripe targets for being brought down to earth with comic ridicule. The very idea of bringing men on stage sporting artificial wings was irresistible. In his Birds of 414 B.C., he has the two heroes set off to found a new city in the sky, and the chorus is made to represent all kinds of birds. They make a convincing case (Birds 785-97) for the practical usefulness of wings:

Never need a Patrocleides, sitting here, his garment stain;

When the dire occasion seized him, he would off with might and main

Flying home, then flying hither, lightened and relieved, again… (tr.B.B. Rogers)

With wings you could avoid boredom, tiredness and hunger, obey a pressing call of nature, even take the opportunity to dally with an old girlfriend while her husband sat with VIPs in the front row of the theatre! Eventually the heroes themselves come on stage with wings attached, and later (lines 1305-11) the Herald warns them to expect an influx of new citizens – all requiring wings! Not only were must there have been wings everywhere on stage, but cratefuls of spares as well. Between rehearsals, chorus members could hardly have resisted testing out their aerodynamic properties on the slopes of the auditorium.

But the emphasis on wings as the means to flight suggests that actual attempts at flight may have suffered from attempting to emulate birds too closely. Mere possession of wings is no guarantee of successful flight. Experimental attemps to fly with wings have continued into recent times. There are several recorded instances from the Middle Ages which suggest a useful analogy with ancient attempts. The most likely outcome is exemplified by the enterprising attempt by an 11th-century Arab scholar called Al-Djawahiri, who climbed onto the roof of a mosque with two large wings made from wood fastened to his body. Launching himself into the air, he plummeted to the ground and died instantly. Other would-be fliers were luckier. Several accounts survive of Giovanni Danti, who was dubbed the ‘Daidalos of Perugia’. In 1498 Danti provided a memorable spectacle by using wings to fly across the main square of Perugia from a high bell-tower, suffering no more than a broken leg when he crashed onto the roof of the church opposite.

No ancient Athenian seems to have attempted a similar feat in the agora, perhaps because there were no buildings high enough to launch themselves from. Adventurers were more likely to head to the suburb of Kerameikos with its multi-storey tenement-blocks. We hear of a building there called the Tall Tower, a place where would-be fliers could risk breaking more than their legs: in Aristophanes’ Frogs (134) when Herakles recommends that Dionysos jump from there, the latter exclaims “But I’d smash up a good pair of brains!” Most would-be flyers would choose to adopt a less precipitate approach. For instance, Lucian’s Ikaromenippus learned to fly gradually, jumping from progressively higher and higher points:

I first tried out the wings by jumping up and down, working my arms and doing what geese do, lifting myself along the ground and running on tiptoe as I flew. When this method began to work well, I experimented more boldly. I climbed up the acropolis and dropped down the cliff right into the theatre. When I had flown down without mishap, I tried out greater heights, taking off from Parnes or Hymettus, flying to Geraneia, and then up to Acrocorinth, over Pholoe and Erymanthus, clear to Taygetus. (Loeb, chh.10-11)

Others will have been put off sooner by the painful consequences. The physician who composed the Hippocratic treatise On Fractures, dated to around the end of the fifth century, actually specifies a class of patients as ‘those who have made a jump from a high place’. He goes on to describe in gruesome medical detail the kind of injuries sustained through their foolhardiness (On Fractures, Loeb Ch.11.1-5):

They come down violently on their heel, get the bones separated, with extravasation from the blood vessels since the flesh is contused about the bone, so that swelling and severe pain result.

To try to fly by flapping with artificial wings is in fact an aeronautically unsound procedure, prone to result in fatality. However, Greeks had one regular opportunity to experiment with such flying devices without keen regard to safety. The annual event at Leucas called the Criminal’s Leap was described thus by Strabo (Loeb Ch. 10.2.9):

It was an ancient custom among the Leucadians, at the annual sacrifice in honour of Apollo, for a criminal to be flung from an outpost of rock for the sake of averting general misfortune. Wings and birds of all kinds were attached to him to lighten the leap by their fluttering. A number of men were stationed all round below the rock in small boats to haul the victim in and make haste to escort him outside their borders.

It must have been like bungee-jumping without a bungee. It was only fair that the criminals who found a way of surviving the Leap were sent into exile and not killed. The obvious thing to use in these circumstances would be not wings, but a parachute of some kind. A Persian innovation, the parasol, made this a real option: the North Doorway at Persepolis has a relief carving illustrating a splendid example. Parasols became a fashion accessory in classical Athens, and one was solemnly paraded at the women’s festival of Skirophoria. In The Greek Myths Robert Graves traces a connection between this custom and the story of Skiron, the jolly giant on the cliff who commanded passers-by to wash his feet, then kicked them into the sea. When Theseus came by, it was Skiron’s turn for the high jump. Graves suggests that Skiron (whose name could in origin be taken to mean ‘parasol-man’) may have attempted a slow descent by exploiting the wind-resistant properties of a linen membrane stretched over a rigid framework: in other words, a hang-glider.

Because most such experiments led nowhere, the ancients tended to believe that asking someone to fly was demanding the impossible. Nero’s demands in this respect exemplified his tyrannical megalomania. We learn from Dio Chrysostom (Discourses 21.9), that if Nero ordered someone to fly, that man would undertake to do it, and for a considerable time he would be maintained in the imperial household in the belief that he would fly. Such imperial caprice meant that fatal experiments continued, and Suetonius (Vit. Caes. 6.12.2) succinctly describes the grisly result of one such attempt made at a Neronian banquet: “At his very first attempt, ‘Icarus’ fell to earth next to the imperial couch, spattering the emperor with his blood”.

Flying in the Ancient World

Part 2: Flying Machines

The notion of manned flight did not come entirely out of the blue. Nature provided ready exemplars of flying creatures. The birds are our teachers, noted the 5th century B.C. polymath Democritus, because from them men have learned how to build and how to sing. Their ability to fly might be riskier to emulate, but Democritus was well aware that physical danger was a great stimulus to inventiveness: after all, he noted, the danger of water had encouraged human beings to learn how to swim. Athens’ ‘golden age’ embraced the notion of skills that could be mastered through systematic instruction. Flying was potentially a skill for which various mechanisms might be sought and found.

The construction of artificial wings (discussed in the previous issue) was only one of the aeronautical techniques investigated in antiquity. In view of the numerous tales about the abduction of virgins by gods in the guise of animals, we should not be surprised to find some consideration by would-be aviators of the use of winged creatures. The idea of an animal on which human beings could fly may have stemmed from the actual use of the horse for riding on and pulling chariots, which for most Greeks would have been the experience most akin to flying. Such methods of land travel were readily extrapolated to air travel. Euripides dramatised the flight of Bellerophon and his fall from the winged horse Pegasus. This was parodied in Aristophanes’ Peace of 421 B.C., where Trygaios arranges to fly to heaven not on a horse, but on a decidedly unheroic dung-beetle.

The staging of these scenarios illustrates how, in this technically-minded period, the reality of a flying-machine had come a step closer with the development of mechanical stage-devices, Greek mēchanai (whence ultimately we get our word ‘machine’). Theatre audiences might now see actors suspended in mid-air, whether in the guise of a deus ex machina in Euripidean tragedy, or a practitioner of high-flown sophistry with his head literally in the clouds. In Peace, the actor was literally hoisted in the air on a mechanically-operated giant wooden beetle. But what goes up must come down, as the philosopher Heraclitus said (well, almost). Eventually the actor playing Trygaios has to break through the mask:

I’m shit-scared, and I’m not joking now.

Hoist-operator, please concentrate! –

The wind’s whistling around my belly-button

and unless you’re careful I’ll be feeding the beetle myself!

Not only do we find such machines in the theatre, but increasingly on the battlefield. The creation of artillery devices raises the question of a possible military application for flying. (One of the main promoters of technological innovation has always been the military industry, whether in promoting technology of making spears and helmets, constructing 5th-century Athens’ war-fleet, designing space-rockets or fighting ‘Star Wars’). The limitations of ancient aeronautical technology would have made control of the air a far-fetched military aim, but its usefulness as an adjunct to naval warfare could be, and was, imagined. In Aristophanes’ Frogs, it’s proposed to put Kinesias (a man well-known for his gravity-defying dithyrambs) to good use by attaching him to a fellow-aviator so that, airborne, they might bombard the enemy fleet with the ancient equivalent of mustard-gas:

Euripides. If Kleokritos was fitted with Kinesias-shaped wings and became airborne above the ocean –

Dionysos. It would look hilarious, but what would be the point?

Euripides. They could carry vinegar-pots and during a sea-battle could spray the enemy in the eyes.

Curiously enough, a 5th-century vase-painting presents the glorious sight of a winged warrior in full armour flying high over a battleship (fig.).

Flying would have offered particular advantages for the most intractable aspect of ancient warfare, the breaking of sieges. In fact, events in the Peloponnesian War foreshadowed advances in siege-engineering, and in 399 B.C. a contest promoted by Dionysius I of Syracuse even led to stirrings of rocket technology: machines such as catapults and ballistas were developed so that heavy projectiles could be propelled for long distances. Thus it was in Sicily, the island where Daidalos once came to land after his flight from Crete, that the technology of flight took a step further forward.

Meanwhile, across the strait in South Italy, a Pythagorean inventor in Tarentum called Zopyrus was shortly to invent a manually operated missile-firer called a gastraphetes. Pythagorean interest in flying may be traced back to the sixth-century sage Pythagoras himself, who according to one account was on one occasion seen at the same hour in places miles apart – proof to his followers that he must have discovered how to fly. We know that Pythagoras’s most famous follower and admirer Empedocles (again a Sicilian) experimented with hollow vessels filled with air. Since he died by falling into Etna’s crater trying to inspect the volcano’s interior, we might suppose that he was experimenting with a hot air device which failed to achieve a controlled descent. Another Pythagorean, Plato’s friend Archytas, experimented with a unique flying mechanism: his mechanical wooden dove seems to have worked using steam-pressure, and the record of the event has the ring of an eye-witness report:

Among many other distinguished Greeks, the philosopher Favorinus, a scrupulous researcher of ancient records, has stated most positively that Archytas made a wooden model of a dove with such mechanical ingenuity and art that it flew. It was finely balanced with weights and propelled by a current of air generated inside it. I will quote Favorinus’ own words since it seems so hard to believe: Archytas of Tarentum, an inventor among other things, built a wooden dove which flew, but after coming to land did not take to the air again. (Aulus Gellius 10.12.8-10)

In the end, however, ancient flying machines never really took off. The idea of guided airborne vehicles remained in the province of fantasy, inspiring one of the most popular legends told about Alexander the Great during the Middle Ages:

When Alexander wished to preside over the air, he had the rather good idea of seating himself, so as to be carried up, on strong flying griffons, holding roasted meats aloft on his sword. The griffons, smelling the food above their heads, pressed upwards in order to eat. When Alexander had risen very high and wished to descend, he turned the meat down below the griffons’ mouths. They, still wanting the food, flew down to try to seize it, and bore Alexander, unharmed and without danger, back to earth. (Giovanni da Fontana, Metrologum).

Military machines were used in battle with spectacular success by Alexander the Great and his successors, and subsequently by the Romans. Later generations marvelled at the wondrous men who invented such mēchanai. In expressing his admiration, the 12th-century author Kekaumenos came close to coining the title of a cinematic account of early aviation: “Those extraordinary men who compiled works on fighting machines and designed battering-rams and mangonels and many other devices…” Clearly the ancient equivalent of Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines!

July 30, 2016

The Savoy Shower Principle

A few months ago, a friend and his wife won a weekend at the Savoy Hotel in a raffle. ‘It was a lovely experience’, said my friend. ‘They completely refurbished the hotel a few years ago, spent more than £200 million. The most amazing thing is the power-showers in the bathrooms – so strong that afterwards you feel like you’ve had a full-body massage .’ ‘You could always get one installed at home’, I said, ‘but I wouldn’t advise it – you’d have to reckon with the Savoy shower principle.’ He was naturally puzzled, so I told him the following story.

My parents-in-law, Dennis and June, got married in London in 1940, during the Blitz. For their honeymoon they booked a weekend at the Savoy Hotel. On their second night the hotel’s windows were blown out by a bomb; but they were having such a good time, it hardly bothered them, and the guests and hotel staff responded with immaculate sang-froid.

Every year thereafter they returned to the Savoy on the anniversary of their wedding. I first joined them there for dinner on their 50th wedding anniversary in 1990. Dennis would say that the highlight for him of staying at the Savoy was that the hotel had such powerful showers in the bathrooms. Every year he looked forward to enjoying a powerful jet-shower, and it never disappointed him. By comparison, he said, the shower at home produced a drizzle. When I suggested that he could install a better shower at home, he looked at me as if I was mad. But a few years later he had to have his home shower replaced, because it was so clogged with limescale that the water flow was reduced to a drip. Naturally, he sought out the make of the Savoy shower and installed one at home.

A few months later the night of their Savoy visit came around, and I joined them for dinner. Dennis was in a deeply disconsolate mood. It’s all changed, he said. What was the problem, I wondered. It’s the shower, he said eventually; compared to the one at home, the shower in the hotel bathroom is feeble. It used to be the main treat of the visit, and now that’s lost. The loss cast a shadow over his stay, and over each of his return visits to the Savoy until he died in 1999.

My friend laughed when I told him the tale. ‘It’s all relative, isn’t it?’ he commented.

Yes, enjoyment, even happiness, is relative. That’s the Savoy shower principle.

March 13, 2016

Catullus’s model boat

The poet Catullus (c. 84-54 BC) imagines showing off to visitors a toy boat, and listening to it describing in its own voice the journey it could claim to have made from a mountain grove in Asia Minor to its final home in Italy.

Catullus, Poem 4: Phaselus ille (‘That little boat’)

You see, my friends, that little model boat?

She claims she was the fastest of her kind,

and that no other piece of wood afloat

could beat her using sails and oars combined.

The Adriatic with its angry mien

will not deny this, she insists, nor will

the winding Cyclades, nor noble queen

of islands, Rhodes, nor Thracian tempests chill,

Nor rough Propontis nor the Pontic sea

where once, before she sat afloat and fair,

she stood in leafy woods, a rustling tree

on Mount Cytorus, creaking in the air.

“You knew my nature then, and know it now,

Pontine Amastris” (so the toy boat says);

‘You too, Cytorus, where the box-trees bow

on ridges where I stood in childhood days

and in your waves first dipped my little oars.

From there across the unresisting tides

my owner ferried me to distant shores,

as winds blew to my port and starboard sides —

or both at once! I never made a vow

to come to port, not once, until I passed

to this unruffled pool, where resting now

I give myself to you, Twin Gods, at last.”

Scholars and readers have long supposed that this charming jeu d’esprit (of which my version in verse is only a slightly loose translation) is about a full-size (boxwood!) yacht that made a real voyage as described, with Catullus on board as its master. In the Latin original underneath I mark in bold some telltale words and phrases which, as part of this cheerfully extravagant ecphrasis, draw the reader’s attention to the more likely interpretation which I argue for in greater detail at the end.

Something like this was first argued long ago in a 1983 article by my predecessor as Classics Fellow at Jesus College Oxford, J.G. Griffith (building on a suggestion by Lenchantin de Gubernatis published in 1928). Then Gordon Williams, in his masterly survey Tradition and Originality in Roman Poetry (1987), argued that the phaselus was depicted on a wall painting. I regret that it has taken me several decades to realise that these scholars were on the right lines, though they are rarely cited or followed in this connection. I lean towards Griffith’s view because of the epithet buxifer (13), but I would go even further and suggest that the phaselus might even be an imaginary model boat…

Phaselus ille, quem videtis, hospites,

ait fuisse navium celerrimus,

neque ullius natantis impetum trabis

nequisse praeterire, sive palmulis

opus foret volare sive linteo. 5

et hoc negat minacis Hadriatici

negare litus insulasve Cycladas

Rhodumque nobilem horridamque Thraciam

Propontida trucemve Ponticum sinum,

ubi iste post phaselus antea fuit 10

comata silva: nam Cytorio in iugo

loquente saepe sibilum edidit coma.

Amastri Pontica et Cytore buxifer,

tibi haec fuisse et esse cognitissima

ait phaselus; ultima ex origine 15

tuo stetisse dicit in cacumine,

tuo imbuisse palmulas in aequore,

et inde tot per impotentia freta

erum tulisse, laeva sive dextera

vocaret aura, sive utrumque Iuppiter 20

simul secundus incidisset in pedem;

neque ulla vota litoralibus diis

sibi esse facta, cum veniret a mari

novissime hunc ad usque limpidum lacum.

sed haec prius fuere: nunc recondita 25

senet quiete seque dedicat tibi,

gemelle Castor et gemelle Castoris.

A few notes on the interpretation:

1. Unlike most interpreters, I doubt that Catullus is describing a sea voyage that he ever actually undertook. I suspect that he returned from Bithynia to Italy overland (cf. pedes in C. 46.8 – and humorously implied here by pedem at 21?). If so, he could have brought with him a model boat, or just a block of boxwood (3, trabs) from which he carved a model boat; and the phaselus could then rightly claim that it’s faster than any ship afloat, since even a cart driven by a muleteer (of which more later) travels much faster than a vessel on water.

But it isn’t Catullus’s journey that is being described here — this is a poem, not autobiography. The journey is supposedly that experienced by the boat itself, as if it were a miniature Argo (cf. Cat. 64, which begins with a reference to the mythical Argo’s origins as a pine tree). So we might just as well suppose that the narrator is presenting a miniature boat made of Asian boxwood (resting on a delightfully novel and ever-unruffled vitreous surface? – novissime hunc ad usque limpidum lacum, 24) — and then imagining, in the object’s own voice, how it got to Italy.

2. All the seas and places mentioned (Adriatic, Cyclades, Rhodes, Thrace, the Black Sea) would, we are told, love to deny the boat’s prowess in the face of their threats and wildness, but they can’t. The double negative negat…negare (6-7) is a telling piece of devilry: the phaselus never actually had such experiences, but it can deny that they are deniable.

3. (Ait) erum tulisse (19) is easily understood either as ‘(the boat says) it carried its master’ or ‘(the boat says) its master carried it’. J.G. Griffiths pointed out the brilliantly ambiguous switch of subject. The erus need not be the poem’s narrator, nor Catullus himself as is commonly assumed, just whoever the boat imagines transported it from its homeland in Asia Minor.

4. There are parallels for making a sea voyage with a phaselus, but the the notion of Catullus coming home from Asia in a ‘pea-boat’ (phaselos means ‘cowpea’ in Greek, rather than ‘kidney-bean’ as it is usually glossed) with ‘little oars’ (palmulae) across the Adriatic, round the Cyclades etc. (the geography is notoriously problematic)… and then storing his yacht of boxwood (not the right wood for a real boat*) on Lake Garda for visitors to look at (let us suppose them to be Furius and Aurelius)…[* Michael Fontaine reminds me via Twitter (21 Sep 16) that a toy spinning-top (turbo) is glossed volubile buxum at Aeneid 7.382].

5. If instead one takes the view that this is purely a jeu d’esprit (cf. nugas, C.1.4), it opens up a new literary perspective, that of ecphrasis (which, surprisingly, has rarely been mentioned in this connection). No one supposes that Theocritus describes a real cup in Idyll 1, or Catullus a real coverlet in Poem 64. (Some even doubt the reality of the sparrow in poem 2). Hellenistic poets used visualised objects — real or imagined — to tell a story. This story may be that of Catullus’s happy return to and retirement at Sirmio (cf. Catullus 31), as told through the mouth of a boat — but it needn’t be (Thomson in his commentary even suggests that the whole thing is set in Egypt, and that it draws on a lost Callimachean poem called ‘the yacht of Berenice’ — but hard evidence is lacking).

6. Does it matter, then, whether the phaselus is real or imaginary, or whether we should imagine a full-size boat or a model? In some ways not. But the poem has more point and wit (cf. Cat.16.7 salem ac leporem) if we are supposed to imagine that the poet is imagining himself pointing out to onlookers a model boat (‘ille’ – ‘that one there’) made of Pontic boxwood, and then reporting the boat’s fantasy about its presumed life-cycle and quasi-Odyssean journey to Italy.

7. Catullus is parodying the genre of dedicatory poems, just as Virgil closely parodies this very poem in Catalepton 10, where the subject is the muleteer Sabinus (representing Ventidius Bassus). The dedication here to the Twin Gods (Castor and Pollux, the gods of sailors) is not to be taken literally, any more than the muleteer’s dedication, or Horace’s dedication of his wet clothes to the god (or goddess) of the sea at the end of Odes 1.5. The only significance here is that the boat, like the poem, has come to its final destination.

August 1, 2015

In memoriam Martin West

The unexpected death (at the age of 77) on 13 July 2015 of Martin West, the greatest classicist of his generation, has left a hole in the world of scholarship and philology.

It also leaves me with a sense of profound personal loss. He was a presence in my life and thinking since I first encountered him 37 years ago. In the past 15 years, we interacted regularly regarding matters that were central to both our interests, not least ancient Greek music. I append here a few mainly personal reminiscences, so that they may not fade from memory as time passes.

When I first met MLW in 1978 I was studying music in London and had just spent much of the summer working slowly through his magnificent, recently-published, commentary on Hesiod’s Works and Days. My prospective Oxford tutor, Nicholas Richardson, had invited me to a Classics event in London, and in the break he introduced me to his former doctoral supervisor: ‘This is Martin West’. I gawped at the sprightly figure, who looked nothing like the grey-haired sage that I assumed had written the magisterial commentary. ‘You’re not the Martin West?’ I said. A worried look crossed his face: ‘That depends on who the Martin West is’, he said. ‘The one who wrote Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient and commentaries on Hesiod,’ I said. His face brightened up: ‘Yes, that’s me.’ ‘But you look so young!’ I exclaimed. ‘Well, I am quite young,’ he retorted cheerfully. ‘How old should I look?’ I turned red with embarrassment, but he had a twinkle in his eye.

Many years later I recounted to him the tale of that first meeting. He had no memory of it, and chuckled with relish. But I  seldom spoke to him without saying something that made me feel as gauche as I did on that occasion. I was far from the only person who felt like that; his shy reserve, and habit of waiting and thinking before responding to any question, even trivial ones, has been well documented. It was said that he was a man of few words in seven languages, and his reticence was bound to cause anxiety to many of his interlocutors. But on quite a few occasions, including a dinner in Jesus in to which I invited him in 2006, and one at All Souls at which I was his guest, I found him forthcoming and humorous about matters great and small. I was surprised to find, however, that he was not as accurately informed in all matters as he was in the Classics; for some reason he was convinced that I had been educated, as he had been, at St Paul’s School, and clearly found it hard to assimilate the fact that this was not the case! It was not an important error, but it made me wonder what the source of his misapprehension was.

seldom spoke to him without saying something that made me feel as gauche as I did on that occasion. I was far from the only person who felt like that; his shy reserve, and habit of waiting and thinking before responding to any question, even trivial ones, has been well documented. It was said that he was a man of few words in seven languages, and his reticence was bound to cause anxiety to many of his interlocutors. But on quite a few occasions, including a dinner in Jesus in to which I invited him in 2006, and one at All Souls at which I was his guest, I found him forthcoming and humorous about matters great and small. I was surprised to find, however, that he was not as accurately informed in all matters as he was in the Classics; for some reason he was convinced that I had been educated, as he had been, at St Paul’s School, and clearly found it hard to assimilate the fact that this was not the case! It was not an important error, but it made me wonder what the source of his misapprehension was.

A few years earlier I had sent him my article on the Greek alphabet, and he had written me a note of thanks (in his rather childlike hand) with the words: ‘I am impressed that you have managed to extract so much out of such slight evidence’. I was uncertain about the connotations of ‘impressed’ in this case. At dinner, however, when he asked me what I was working on, I said I’d just written a piece about ancient music, but had held off from sending it to him. ‘I’m worried you might find it too fanciful’ I said — ‘fanciful’ was one of his characteristic words of criticism. ‘But you’re one of the classicists whose work I’ve always thought worth reading’, he said straightforwardly. It was a heart-warming endorsement from such a great scholar.

I knew that he could be kind to his students and to those of whose scholarship he approved, but he could also appear sharp and unforgiving in writing about others’ work. This was mainly because of his desire for unvarnished accuracy. I discovered this when, having returned to academia to do my PhD at UCL in 1994, I submitted my first article to Classical Quarterly in 1996. The article presented an original solution to a long-standing problem in Greek musical history, one of the subjects in which West had become an acknowledged world expert following the publication of his book Ancient Greek Music in 1992. I had given reasons to dispute and augment some of his statements in my article. When the anonymous referee’s report came back to me, my heart fell because it appeared to be a page of blunt dismissals of some of my less well-supported points. My supervisor Richard Janko immediately recognised the style of MLW; and I initially assumed that the catalogue of my apparent howlers would disqualify my piece from publication. However, the page was headed by the brief sentence ‘This is an important and original article and should be published in some form’. When I spoke to the journal’s editor Stephen Heyworth he assured me that from the hand of this referee that was a strong recommendation, and in the event I was immensely grateful that I could take advantage of West’s unparalleled knowledge of the subject in revising the piece.

Before my article was published, I was invited to present it as a talk at an Oxford Seminar series in Corpus. Around 15 scholars including Ewen Bowie, Robin Osborne, and Martin West were present as I set out the reasoning that had led me to my conclusions. At the end of my 55-minute presentation, the audience were invited to ask questions. There was a long silence; it felt as if all present were waiting for MLW to cast the first stone. He was scrutinising my handout, but eventually looked up and announced to all and sundry ‘This is absolutely right’. There was an audible reaction — intakes of breath and murmurs of assent or surprise — to this pronouncement. Afterwards Ewen Bowie said he had never heard MLW be so complimentary at a seminar; I must have slipped something into his drink! But I have heard West being even more complimentary. At a seminar I organised on ancient music in 2013, the astoundingly clever Stefan Hagel gave a paper applying statistical methods to the singing of Pindar, at the end of which MLW simply observed ‘Well of course, this is brilliant’ — to a similar audible reaction. Strangely, after my seminar presentation I chatted to West and said I gathered that he had already refereed the article on which my presentation was based. To my astonishment he denied it. I was relieved when the following day I received a note from him saying that on checking his papers he had discovered that he had indeed written the report; his recent work having turned his attention away from music, he had not remembered having done so.

West’s reputation as a stern critic was reinforced by the stringent tone of some of his reviews. He dismissed three poststructuralist scholars in print with the searing (but brilliantly funny) characterisation of them as ‘a curious tricolour…the Raw, the Cooked, and the Half-baked’; and he once expressed exasperation at an eminent Professor’s failure to distinguish ‘oral’ from ‘orally composed’ poetry in a review which ended with the extraordinarily patronising comment (unacceptable from the pen of any other reviewer) that the latter ‘really must try to get his capacious head round the difference’. MLW was uninhibited about writing things the way he saw them, no doubt because of a particular condition of mind that accompanied his own brilliance. I was bound to feel the edge of his sharp pen from time to time. I felt personally chastised when, in a review for the Journal of Hellenic Studies, he dismissed (I think unfairly) another scholar’s book that I had recommended for publication, ending the review with the words ‘OUP were badly advised in this case’. When I spoke at a conference on Greek music in 2014 I commented that a number of features of the Seikilos inscription had made me wonder fleetingly if it was an accomplished forgery; I received a sharply reproving email from MLW (‘out of the question’), ending with the words ‘you should rather question your own presuppositions about Greek music’. Of course I felt he had his blind spots about music, which he approached as a philologist rather than as a musician: thus I was never able to persuade him that while Greek strophic music might show precise metrical correspondence, this did not require that the melody was repeated note-for-note (as in a Church hymn) from stanza to stanza. I greatly regret that I did not have the chance to draw his attention to the practical demonstration of my ethnomusicologically supported view, in a BBC 4 programme which came out 2 months before he died, where two stanzas of Sappho’s Brothers poem are sung in Mixolydian mode but with different melodic contours based on word-pitch.

I once posted Martin an offprint from my home in London, and received a note of thanks in which he wrote, à propos of nothing much, ‘I was curious to see your home address; a former girlfriend of mine lived on the same street’. (I knew he had once lived in NW3, in the same house as the Roman historian John North, because Alan Griffiths told me he’d once posted a letter to the latter in NW3 wittily addressed, in homage to Hitchcock, ‘North bei North-West’). In Ancient Greek Music, MLW muses about the difficulty of translating ‘auletris’, the term used for a female player of the aulos and standardly translated ‘flute-girl’. The traditional translation ‘flute’ is misleading — auloi were pipes with double reeds; while the performers were more often experienced entertainers than youngsters. He reluctantly offers ‘pipe’ and ‘shawn’ for the instrument, and adds ‘I have found no very satisfactory solution to the girl problem.’ Whatever the point of this humorous double entendre, I more than once witnessed his ability to charm young women, as he surely did in the case of his delightful and clever wife Stephanie (the tale of whose first visit to Delphi with him he briefly and amusingly tells in that book). Once at coffee during a conference at Oxford I introduced him to an attractive young colleague from another place. ‘You look like the kind of person who would enjoy studying X’, he said to her, naming an obscure ancient poet. She gasped with astonishment — ‘X is the very poet I’m studying at the moment!’ He kept up the appearance of sage clairvoyance for a minute or two before admitting that he had seen her name on the list of delegates and noted that she had said she was studying the works of X. But by his humorous subterfuge he had broken the ice immediately, and the conversation flowed.

One of the first articles that I read of the many he had written was his edition (with R. Merkelbach) of a papyrus with a newly discovered erotic poem by the lyric poet Archilochus of Paros; West enjoyed Peter Green’s quip that the poem’s title should be ‘Last Tango in Paros’. On one occasion I made a casual reference to the fact that he must have written hundreds of articles and at least a dozen books. He looked at me quizzically: ‘Thirty-three books to date’, he corrected me. It’s a reminder of what a scholarly phenomenon he was, but for many like myself his death also feels like a personal loss. A Festschrift in his honour appeared in 2007 under the title Hesperos, Greek for ‘West’, and the shock of hearing of his death brought to my mind Callimachus’s lovely epigram on Heraclitus, the first couplet of which I adapted in honour of MLW-Hesperos:

εἶπέ τις, Ἕσπερε δῖε, τεὸν μόρον, ἐς δέ με δάκρυ

ἤγαγεν, ἐμνήσθην δ´ὡς ἅρ᾽ ἔγραψας ἅλις.

They told me, brilliant West, that you had died;

I thought of all you’d written, and I cried.

March 8, 2015

Ovid, the Latin lover

Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid), Roman poet, born 20 March 43 BC

Ovid’s Amores 1.5: the poet’s most upbeat erotic composition in translation.

Midday: a long, hot afternoon ahead;

I threw my weary body on the bed.

The blinds, half-shut, half-open to the breeze,

cast dappled beams like sunlight through the trees:

the light that comes from sun’s departing ray,

or when night ends and yields to break of day,

the murky gloom that decent girls require

to guard the reputation they desire.

In comes Corinna, clad in low-slung frock,

her neck agleam, each side a tumbling lock.

So came Semíramis the fair, ’tis said,

and Laïs, beloved of many men, to bed.

I tore the frock off. Little though it hid,

she fought to keep it on, a token bid:

for since she did not really fight to to win,

my victory was easy — she gave in.

Clothes cast aside, she stood in front of me,

from head to toe a figure blemish-free.

What arms to dwell on, shoulder-blades to press;

What nipples standing firm at my caress.

What slender waist, what breasts, what firm young thighs,

what lissom hips to captivate my eyes.

Why list them all? She simply looked divine.

I pulled her naked body hard to mine.

The rest you know. Worn out, we slept entwined.

May I enjoy more noondays of this kind.

Aestus erat, mediamque dies exegerat horam;

adposui medio membra levanda toro.

pars adaperta fuit, pars altera clausa fenestrae.

quale fere siluae lumen habere solent,

qualia sublucent fugiente crepuscula Phoebo 5

aut ubi nox abiit nec tamen orta dies.

illa verecundis lux est praebenda puellis,

qua timidus latebras speret habere pudor.

ecce, Corinna venit tunica velata recincta,

candida dividua colla tegente coma, 10

qualiter in thalamos formosa Sameramis isse

dicitur et multis Lais amata viris.

deripui tunicam! nec multum rara nocebat,

pugnabat tunica sed tamen illa tegi;

quae, cum ita pugnaret tamquam quae vincere nollet, 15

victa est non aegre proditione sua.

ut stetit ante oculos posito velamine nostros,

in toto nusquam corpore menda fuit:

quos umeros, quales vidi tetigique lacertos!

forma papillarum quam fuit apta premi! 20

quam castigato planus sub pectore venter!

quantum et quale latus! quam iuvenale femur!

singula quid referam? nil non laudabile vidi,

et nudam pressi corpus ad usque meum.

cetera quis nescit? lassi requieuimus ambo. 25

proveniant medii sic mihi saepe dies.

March 31, 2014

Song of the Sirens

‘Nobody has ever made head or tail of ancient Greek music, and nobody ever will. That way madness lies’. Quoted by Wilfred Perrett in a talk given in 1932 to the Royal Musical Association.

‘Nobody has ever made head or tail of ancient Greek music, and nobody ever will. That way madness lies’. Quoted by Wilfred Perrett in a talk given in 1932 to the Royal Musical Association.

‘Research into ancient Greek music is pointless’. Giuseppe Verdi.

Is it really so hopeless? During 2013-15 I conducted a research project (funded by the British Academy and Jesus College Oxford) to reconstruct the sound and significance of ancient Greek music. I travelled to countries where traditions that stem from ancient Greek pipe-playing, string-playing and melodic systems are still to be found in various forms. I’ve lectured widely on and written several scholarly articles about my findings, and hope to write a reasonably accessible book on the subject. The following is an outline of the project, and a 4-minute taster film gives an idea of how exciting it is.

At the root of all Western literature is ancient Greek poetry – Homer’s great epi cs, the passionate love poems of Sappho, the masterpieces of Greek tragedy and of comic theatre. But few people know or care that almost all of this poetry was or originally involved sung music, often with instrumental accompaniment. Imagine that all we knew of the Beatles songs – or the operas of Mozart, Verdi, Wagner and Britten – were the words. Then a

cs, the passionate love poems of Sappho, the masterpieces of Greek tragedy and of comic theatre. But few people know or care that almost all of this poetry was or originally involved sung music, often with instrumental accompaniment. Imagine that all we knew of the Beatles songs – or the operas of Mozart, Verdi, Wagner and Britten – were the words. Then a fter two millennia we had the means to rediscover what the music sounded like. We would be bound to recognise the huge difference the sound of music makes to the listeners’ minds and emotions. Imagine.

fter two millennia we had the means to rediscover what the music sounded like. We would be bound to recognise the huge difference the sound of music makes to the listeners’ minds and emotions. Imagine.

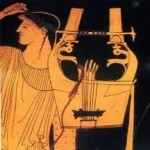

Music was as central to Greek life as it is to ours. Greeks believed that music had the power to captivate and enchant. In the case of the Sirens’ song, it could beguile listeners to th eir death. In the fifth century BC, the music of Athenian theatre was enjoyed by tens of thousands of listeners. Top performers were treated like pop stars. The piper Pronomos of Thebes was said, like Elvis himself, to have ‘delighted the audience with his facial expressions and the movements of his body’.

eir death. In the fifth century BC, the music of Athenian theatre was enjoyed by tens of thousands of listeners. Top performers were treated like pop stars. The piper Pronomos of Thebes was said, like Elvis himself, to have ‘delighted the audience with his facial expressions and the movements of his body’.

We are now in a position to reconstruct from surviving documents how Greek music actually sounded. By combining this knowledge with modern analogies and imaginative musicianship we may make a start at understanding why it was thought to exert such extraordinary power.

The principal components of Greek music — as of all music — were the voice, instruments, rhythms, and melodies. The instruments are well known from ancient paintings and surviving relics, some in excellent condition. Two main kinds of instrument, the double-pipe (auloi) and the lyre, were used to accompany song. In Sardinia we can still hear the penetrating sound of double pipes as play ed by maestro Luigi Lai, preserving an age-old tradition of pipe-playing that was said to have accompanied the devotees of Dionysus in their ecstatic dances. The sweet sound of plucked strings, which can still be heard in ancient tunings played on instruments such as the Turkish oud, empowered the minstrel Orpheus to entrance trees and subdue wild animals.

ed by maestro Luigi Lai, preserving an age-old tradition of pipe-playing that was said to have accompanied the devotees of Dionysus in their ecstatic dances. The sweet sound of plucked strings, which can still be heard in ancient tunings played on instruments such as the Turkish oud, empowered the minstrel Orpheus to entrance trees and subdue wild animals.

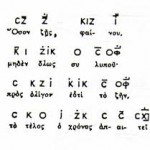

The complex rhythms of Greek poetry in terms are usually studied in terms of metre . This is treated a purely quantitative exercise, indicating the way syllables of long and short duration were arranged into familiar and

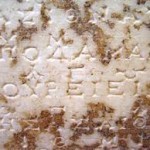

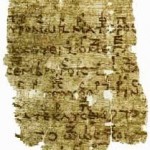

. This is treated a purely quantitative exercise, indicating the way syllables of long and short duration were arranged into familiar and  repetitive patterns. But these patterns were also the basis of dance steps, which involved the rise and fall of dancers’ feet. There must have been a beat in addition to time durations, but where did it fall? Marks on stone and papyrus show how the beat fell in some cases of ancient rhythm, and help us to work out how the brilliant and intricate rhythms may have been danced.

repetitive patterns. But these patterns were also the basis of dance steps, which involved the rise and fall of dancers’ feet. There must have been a beat in addition to time durations, but where did it fall? Marks on stone and papyrus show how the beat fell in some cases of ancient rhythm, and help us to work out how the brilliant and intricate rhythms may have been danced.

Finally, we are now in a position to hear some of the melodies that were actually heard in ancient Greece. Until recently, people thought we knew nothing of ancient tunes. Scholarship has now accurately deciphered marks on stone and papyrus that reveal song s and scraps of tunes, some of which haven’t been heard for 2000 years. The latest of these pagan melodies, dating from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, are audibly related to the sung music at the beginnings of the Western musical tradition as we know it, 9th-century Gregorian plainsong.

s and scraps of tunes, some of which haven’t been heard for 2000 years. The latest of these pagan melodies, dating from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, are audibly related to the sung music at the beginnings of the Western musical tradition as we know it, 9th-century Gregorian plainsong.

With care we may be able to reconstitute some of the sounds of ancient Greek music. By combining different aspects of scholarly expertise, we may perhaps attempt to recreate the sound of an ancient Euripidean chorus, or even to realise a haunting passage in Homer’s Odyssey – to hear the song the Sirens sang.

With care we may be able to reconstitute some of the sounds of ancient Greek music. By combining different aspects of scholarly expertise, we may perhaps attempt to recreate the sound of an ancient Euripidean chorus, or even to realise a haunting passage in Homer’s Odyssey – to hear the song the Sirens sang.

September 24, 2012

Losers and winners

Coming last in style

The ancient Greeks didn’t always treat athletes and athletics with reverence. Nicarchus (1st cent. AD) wrote a witty epigram about runner called Kharmos (‘Victor’), which I’ve translated as follows:

When Kharmos, in Arcadia, once entered in a race

competing with five runners, he came out in seventh place.

A curious result, and you’ll be saying ‘How in heaven,

with six men in the race, did Kharmos finish no. 7?’

The reason’s this. A mate of Kharmos, shouting ‘Go, you’re fine’

ran fully dressed around the course, and beat him to the line.

So Kharmos finished seventh, but here’s to his sporting health:

if he had five more friends, just think — he would have finished twelfth.

πέντε μετ᾽ ἄλλων Χάρμος ἔν ᾽Αρκαδίᾳ δολιχεύων,

θαῦμα μέν, ἀλλ᾽ὄντως ἕβδομος ἐξέπεσεν.

«ἓξ ὄντων», τάχ᾽ἐρεῖς, «πῶς ἕβδομος;» εἷς φίλος αὐτοῦ

«θάρσει, Χάρμε», λέγων ἦλθεν ἐν ἱματίῳ.

ἕβδομος οὖν οὕτω παραγίνεται· εἰ δ᾽ἔτι πέντε

εἶχε φίλους, ἦλθ᾽ἄν, Ζωΐλε, δωδέκατος.

Mark Ives, who teaches Classics at St Gabriel’s School in Newbury, drew my attention to another example of Nicarchus’s epigrammatic wit (Greek Anthology 11.395):

Πορδὴ ἀποκτέννει πολλοὺς ἀδιέξοδος οὖσα·

πορδὴ καὶ σώζει τραυλὸν ἱεῖσα µέλος.

οὐκοῦν εἰ σώζει, καὶ ἀποκτέννει πάλι πορδή,

τοῖς βασιλεῦσιν ἴσην πορδὴ ἔχει δύναµιν.

I translate:

A fart, repressed, brings many to their death;

Released it rescues with its rasping breath.

So if a fart can save or cause death’s hour,

To kings it surely has an equal power.

Heraclitus

They told me, Heraclitus, they told me you were dead;

They brought me bitter news to hear and bitter tears to shed;

I wept as I remembered how often you and I

Had tired the sun with talking, and sent him down the sky.

And now that thou art lying, my dear old Carian guest,

A handful of grey ashes, long, long ago at rest,

Still are thy pleasant voices, thy nightingales, awake;

For Death, he taketh all away, but them he cannot take.

William Johnson Cory was the Victorian Eton schoolmaster who wrote this haunting translation of an ancient Greek epigram, Callimachus’ lament for his friend the poet (not the much earlier philosopher) Heraclitus. In Greek (Callimachus Ep. 2 Pfeiffer) it consists of three taut and simple elegiac couplets:

Εἶπέ τις, Ἡράκλειτε, τεὸν μόρον, ἐς δέ με δάκρυ

ἤγαγεν. ἐμνήσθην δ᾿ ὁσσάκις ἀμφότεροι

ἠέλιον λέσχῃ κατεδύσαμεν, ἀλλὰ σὺ μέν που,

ξεῖν᾿ Ἁλικαρνησεῦ, τετράπαλαι σποδιή.

αἱ δὲ τεαὶ ζώουσιν ἀηδόνες, ᾗσιν ὁ πάντων

ἁρπακτὴς Ἀίδης οὐκ ἐπὶ χεῖρα βαλεῖ.

My translation here aims to capture the less sentimental quality of the original:

Someone mentioned, Herakleitos, you were dead, and tears

came to my eyes. It brought to mind the times we two

had seen the sun set on our conversations; ah, but you,

my friend from Halikarnassos, have been ashes all these years.

Your songs, your nightingales, live on; though greedy Death commands

that all come to his realm, on these he will not lay his hands.

Cory also wrote the paragraph below, summing up what he saw to be the purpose of education at Eton. It expresses sentiments that nowadays might be more apt to education at university level (at least in places like Oxford and Cambridge where the tutorial system still exists) than to the more inflexible style of schoolteaching required to achieve good results in the league tables.

The shadow of lost knowledge

At school you are engaged not so much in acquiring knowledge as in making mental efforts under criticism. A certain amount of knowledge you can indeed with average faculties acquire so as to retain; nor need you regret the hours you spent on much that is forgotten, for the shadow of lost knowledge at least protects you from many illusions. But you go to a great school not so much for knowledge as for arts and habits; for the habit of attention, for the art of expression, for the art of assuming at a moment’s notice a new intellectual position, for the art of entering quickly into another person’s thoughts, for the habit of submitting to censure and refutation, for the art of indicating assent or dissent in graduated terms, for the habit of regarding minute points of accuracy, for the art of working out what is possible in a given time, for taste, for discrimination, for mental courage, and for mental soberness. Above all, you go to a great school for self-knowledge.

To this marvellous paragraph might be added the equally splendid essay by the conservative political philosopher Michael Oakeshott, written in 1950, entitled The Idea of a University. It is worth reading in full, but perhaps its most ringing paragraphs are the following: