Michael R. Brasher's Blog, page 3

October 10, 2019

Detached Duty and the Suffolk Campaign

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment:

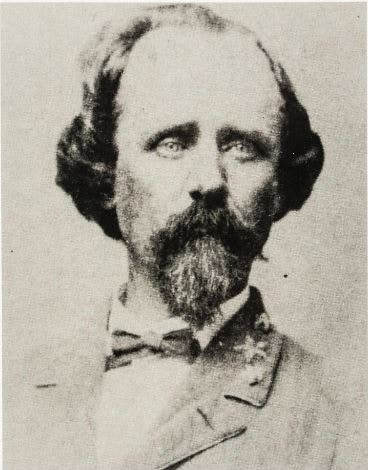

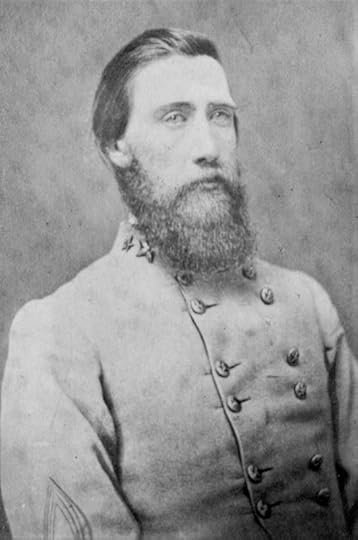

Detached Duty and the Suffolk Campaign Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis Following the retreat from Maryland, on November 8, 1862, Special Order 236 directed that the 2nd and 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiments be detached from the army and report to Richmond. There, the two veteran regiments were joined by the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina, two recently organized (May 1862) “green” regiments that had not yet seen combat.[1] These four regiments formed a new brigade under the command of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis, a Mississippian and Jefferson Davis’ nephew. Davis’ Brigade was sent to Goldsborough, North Carolina where the 2nd Mississippi spent a relatively pleasant winter, missing the battle of Fredericksburg, and recovering from some of its campaign losses. Wounded and sick recovered and returned to the ranks, and those taken prisoner were exchanged. However, unlike the previous winter, only a handful of new recruits joined the regiment.[2]

Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis Following the retreat from Maryland, on November 8, 1862, Special Order 236 directed that the 2nd and 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiments be detached from the army and report to Richmond. There, the two veteran regiments were joined by the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina, two recently organized (May 1862) “green” regiments that had not yet seen combat.[1] These four regiments formed a new brigade under the command of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis, a Mississippian and Jefferson Davis’ nephew. Davis’ Brigade was sent to Goldsborough, North Carolina where the 2nd Mississippi spent a relatively pleasant winter, missing the battle of Fredericksburg, and recovering from some of its campaign losses. Wounded and sick recovered and returned to the ranks, and those taken prisoner were exchanged. However, unlike the previous winter, only a handful of new recruits joined the regiment.[2]

With the Federals gaining a beachhead on the Virginia coast south of the James River in February 1863, Lee dispatched two divisions, Hood’s and Pickett’s, to guard the southern approaches to Richmond and Petersburg. Micah Jenkins’ and Davis’ brigades were ordered up from Goldsborough to southern Virginia, where they formed a division under the command of Major General Samuel G. French. Lee ordered Longstreet, on February 18th, to take command of the Southern forces concentrating along the Blackwater River. His orders were to defend Richmond while holding his men ready to return to the main army if needed. Longstreet was also directed to forage for provisions for the undernourished Army of Northern Virginia and, if the opportunity presented itself, to take the offensive against the Federal forces in his front.[3]

Following weeks of scouting, foraging and skirmishing along the Blackwater River, the 2nd Mississippi was involved in Longstreet’s unsuccessful siege of Suffolk, Virginia from April 11th to May 4, 1863. Although actual fighting was light, the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina received their “baptism of fire” during a reconnaissance in force upon the Confederate lines by the 99th New York on May 1st.[4]

Longstreet had already begun planning the return of his forces to the main army, even as the Confederates were repulsing the Federal probe of the 99th New York. The new commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph Hooker, was attempting to execute a bold plan to destroy Lee’s army. He already had crossed the Rappahannock River and was threatening Lee’s left flank. Although the divisions of Hood and Pickett began a hurried departure, they did not arrive in time to participate in the Battle of Chancellorsville, often characterized as Lee’s greatest victory, but resulting in tragic consequences for the South. Stonewall Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men on May 2nd, losing an arm and dying of complications from pneumonia a few days later.[5]

With Jackson’s death and Longstreet’s return, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia. From the original two-wing structure, three infantry corps were created. Longstreet retained the First Corps, the Second was placed under the command of newly promoted Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, and the new Third Corps was given to the also recently promoted Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill. A new division under Major General Henry Heth, to which Davis’ Brigade was assigned, was also placed in Hill’s Corps. On June 5th the 2nd Mississippi, with the balance of Davis’ Brigade, left southern Virginia to join the new division. The regiment would remain within this organizational structure (Davis’ Brigade, Heth’s Division, Hill’s Third Corps, Army of Northern Virginia) for the remainder of the war.[6]

[1] Joseph H. Crute, Jr., Units of the Confederate States Army (Midlothian, VA, 1987), pp. 187-188, 239; Stewart Sifakis, Compendium of the Confederate Armies: Mississippi (New York, 1995), pp. 133-134, North Carolina, pp. 155-156; InfoConcepts, Inc., The American Civil War Regimental Information System: Volume I --the Confederates (Albuquerque, 1994, 1995), computer database software.

[2] O.R., 19, pt. 2, p. 705.

[3] O.R., 18, p. 883; Mark M. Boatner, III, The Civil War Dictionary (New York, 1991), p. 817.

[4] Ibid.; Steven A. Cormier, The Siege of Suffolk: The Forgotten Campaign, April 11-May 4, 1863 (Lynchburg, VA, 1989), 246-248.

[5] Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville (Boston, 1996), pp. 117-121, 293-297, 446-448.

[6] Ray F. Sibley, Jr. The Confederate Order of Battle: The Army of Northern Virginia, Volume 1, (Shippensburg, 1996), p. 52; O.R., 27, pt. 3, p. 860.

Detached Duty and the Suffolk Campaign

Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis Following the retreat from Maryland, on November 8, 1862, Special Order 236 directed that the 2nd and 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiments be detached from the army and report to Richmond. There, the two veteran regiments were joined by the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina, two recently organized (May 1862) “green” regiments that had not yet seen combat.[1] These four regiments formed a new brigade under the command of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis, a Mississippian and Jefferson Davis’ nephew. Davis’ Brigade was sent to Goldsborough, North Carolina where the 2nd Mississippi spent a relatively pleasant winter, missing the battle of Fredericksburg, and recovering from some of its campaign losses. Wounded and sick recovered and returned to the ranks, and those taken prisoner were exchanged. However, unlike the previous winter, only a handful of new recruits joined the regiment.[2]

Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis Following the retreat from Maryland, on November 8, 1862, Special Order 236 directed that the 2nd and 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiments be detached from the army and report to Richmond. There, the two veteran regiments were joined by the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina, two recently organized (May 1862) “green” regiments that had not yet seen combat.[1] These four regiments formed a new brigade under the command of Brigadier General Joseph R. Davis, a Mississippian and Jefferson Davis’ nephew. Davis’ Brigade was sent to Goldsborough, North Carolina where the 2nd Mississippi spent a relatively pleasant winter, missing the battle of Fredericksburg, and recovering from some of its campaign losses. Wounded and sick recovered and returned to the ranks, and those taken prisoner were exchanged. However, unlike the previous winter, only a handful of new recruits joined the regiment.[2]With the Federals gaining a beachhead on the Virginia coast south of the James River in February 1863, Lee dispatched two divisions, Hood’s and Pickett’s, to guard the southern approaches to Richmond and Petersburg. Micah Jenkins’ and Davis’ brigades were ordered up from Goldsborough to southern Virginia, where they formed a division under the command of Major General Samuel G. French. Lee ordered Longstreet, on February 18th, to take command of the Southern forces concentrating along the Blackwater River. His orders were to defend Richmond while holding his men ready to return to the main army if needed. Longstreet was also directed to forage for provisions for the undernourished Army of Northern Virginia and, if the opportunity presented itself, to take the offensive against the Federal forces in his front.[3]

Following weeks of scouting, foraging and skirmishing along the Blackwater River, the 2nd Mississippi was involved in Longstreet’s unsuccessful siege of Suffolk, Virginia from April 11th to May 4, 1863. Although actual fighting was light, the 42nd Mississippi and 55th North Carolina received their “baptism of fire” during a reconnaissance in force upon the Confederate lines by the 99th New York on May 1st.[4]

Longstreet had already begun planning the return of his forces to the main army, even as the Confederates were repulsing the Federal probe of the 99th New York. The new commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph Hooker, was attempting to execute a bold plan to destroy Lee’s army. He already had crossed the Rappahannock River and was threatening Lee’s left flank. Although the divisions of Hood and Pickett began a hurried departure, they did not arrive in time to participate in the Battle of Chancellorsville, often characterized as Lee’s greatest victory, but resulting in tragic consequences for the South. Stonewall Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men on May 2nd, losing an arm and dying of complications from pneumonia a few days later.[5]

With Jackson’s death and Longstreet’s return, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia. From the original two-wing structure, three infantry corps were created. Longstreet retained the First Corps, the Second was placed under the command of newly promoted Lieutenant General Richard Ewell, and the new Third Corps was given to the also recently promoted Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell Hill. A new division under Major General Henry Heth, to which Davis’ Brigade was assigned, was also placed in Hill’s Corps. On June 5th the 2nd Mississippi, with the balance of Davis’ Brigade, left southern Virginia to join the new division. The regiment would remain within this organizational structure (Davis’ Brigade, Heth’s Division, Hill’s Third Corps, Army of Northern Virginia) for the remainder of the war.[6]

[1] Joseph H. Crute, Jr., Units of the Confederate States Army (Midlothian, VA, 1987), pp. 187-188, 239; Stewart Sifakis, Compendium of the Confederate Armies: Mississippi (New York, 1995), pp. 133-134, North Carolina, pp. 155-156; InfoConcepts, Inc., The American Civil War Regimental Information System: Volume I --the Confederates (Albuquerque, 1994, 1995), computer database software.

[2] O.R., 19, pt. 2, p. 705.

[3] O.R., 18, p. 883; Mark M. Boatner, III, The Civil War Dictionary (New York, 1991), p. 817.

[4] Ibid.; Steven A. Cormier, The Siege of Suffolk: The Forgotten Campaign, April 11-May 4, 1863 (Lynchburg, VA, 1989), 246-248.

[5] Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville (Boston, 1996), pp. 117-121, 293-297, 446-448.

[6] Ray F. Sibley, Jr. The Confederate Order of Battle: The Army of Northern Virginia, Volume 1, (Shippensburg, 1996), p. 52; O.R., 27, pt. 3, p. 860.

Published on October 10, 2019 15:55

October 5, 2019

South Mountain and Antietam

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment:

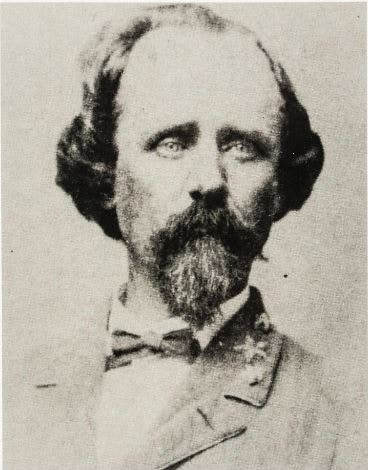

South Mountain and Antietam Major General John Bell Hood

Major General John Bell Hood

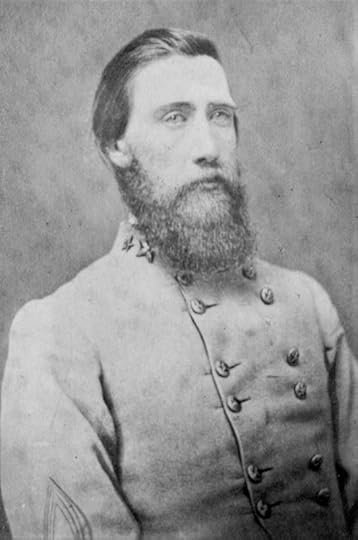

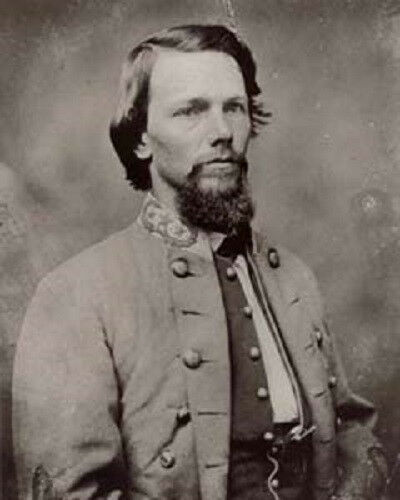

Colonel Evander Law The usually cautious McClellan’s newfound sense of aggressiveness was fostered by the discovery on September 13th of a copy of Lee’s campaign plans outlining the division of the Confederate army and routes of march. On September 14th, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Southern forces detached to guard the two passes through South Mountain, Maryland. Responding to the seriousness of the threat, Longstreet ordered Hood back from Hagerstown via Boonsboro to reinforce the Confederate defenders at Turner’s Gap. Immediately upon arriving, Hood deployed Law’s Brigade and his Texans, and in a counterattack, drove the Federals back at bayonet point. The 2nd Mississippi suffered approximately 17-18 casualties, mostly wounded and captured.[1]

Colonel Evander Law The usually cautious McClellan’s newfound sense of aggressiveness was fostered by the discovery on September 13th of a copy of Lee’s campaign plans outlining the division of the Confederate army and routes of march. On September 14th, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Southern forces detached to guard the two passes through South Mountain, Maryland. Responding to the seriousness of the threat, Longstreet ordered Hood back from Hagerstown via Boonsboro to reinforce the Confederate defenders at Turner’s Gap. Immediately upon arriving, Hood deployed Law’s Brigade and his Texans, and in a counterattack, drove the Federals back at bayonet point. The 2nd Mississippi suffered approximately 17-18 casualties, mostly wounded and captured.[1]

At nightfall, Lee fell back from the gaps with Hood’s Division acting as rear guard. Although a more prudent commander would have probably fallen back across the Potomac into Virginia, Lee chose to stand and fight. He concentrated his forces in a strong defensive position on the west side of Antietam Creek around the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland. He wanted to maintain this position to block any attempted advance by McClellan and allow time to complete the capture of Harpers Ferry and its garrison.[2]

Tired and hungry, the men of the 2nd Mississippi found it necessary to again advance against the Federals at dusk on the evening of September 16th. Elements of the Army of the Potomac had crossed Antietam Creek north of Lee’s army and were moving into positions opposite the Confederate left flank. Hood was ordered into the East Woods, a small woodlot which was being infiltrated by Federal skirmishers. Law’s Brigade, in skirmish order just north of the East Woods, was suddenly met by a reconnaissance party of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves (“Bucktails”). The Bucktails, with their Sharps breechloading rifles, used their enhanced firepower to turn the slow withdrawal of Law’s skirmishers into a stampede as they neared the edge of the woods. Luckily, the 4th and 5th Texas arrived to hit the Pennsylvanians simultaneously from the west and south, supported by a section of howitzers from Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion. By 8:00 p.m. however, most of Hood’s units had fallen back to the West Woods for the night. As darkness fell, Law’s Brigade soon came under Federal artillery fire from the batteries to their right on the other side of Antietam Creek.[3]

As night approached, the men lay in the West Woods, facing north while the Union heavy guns fired down the length of their lines from the east. Luckily, most of the shots fell just in front or rear of the Confederate positions. However, the colonel of the 11th Mississippi, Phillip Liddell, was struck in the torso by a bursting shell fragment and would die two days later.[4]

Sometime after midnight, Hood’s men were relieved and allowed to get some rest and food. Other than a half ration of beef and some green corn, they had not eaten for three days. As most of the men wearily returned to their original positions near the Dunker Church, details from each company were sent to forage for food and prepare a morning meal.[5]

The men of the 2nd Mississippi were awakened on the morning of September 17th while it was still dark. Although Hood had persuaded General Lee to allow the division to stay in reserve long enough for the men to eat their long-overdue meal, McClellan’s battle plans did not cooperate. Shells began to fall near the Dunker Church in preparation for a Federal assault on the Confederate left. Law was forced to order the still-hungry men to fall into ranks and prepare for battle.[6]

Somewhat after 6:00 a.m., Colonel Law moved his brigade in columns east across the Hagerstown Pike, where it turned north and deployed in a single battle line. The 2nd Mississippi under Colonel Stone anchored the extreme left of Law’s line, while next came the 11th Mississippi, 6th North Carolina and 4th Alabama on the extreme right. To the left of the 2nd Mississippi the Texas Brigade was similarly deployed in line, with the 1st Texas on the right of the brigade. Law’s men advanced into the Miller Cornfield in a generally northerly direction, loading and firing as they went, except for the 4th Alabama, which moved by the right flank down the Smoketown Road toward the East Woods. The veteran fighters of the 2nd and 11th Mississippi and the 6th North Carolina savagely drove the Federals out of the Cornfield (probably upset at having their long-anticipated breakfasts interrupted). They then reformed along a rail fence at the northern edge of the field, continuing to fire at Federal batteries and infantry units coming onto the scene. At one point, the Confederate line rose and fired at a mere thirty feet distance into the 4th and 8th Pennsylvania Reserves, panicking them, which in turn, panicked the 3rd Pennsylvania Reserves in their rear. As the Federals regrouped and additional reinforcements arrived, however, Hood’s men saw they could not continue to hold their position without help. Union soldiers were infiltrating the gap that had developed between the 6th North Carolina’s right flank and the 4th Alabama’s left, slowed by its advance into the East Woods. The men had to fall back. As Law’s men withdrew, the northern border of the Cornfield along the fence was marked by a long precise, row of Mississippians, stuck down where they stood by one terrible fire.[7]

Hood’s punishing counterattack into the Miller Cornfield had saved the Confederate left, but at a terrible cost. As the survivors retired behind the Dunker Church, they found only about 700 unwounded men of approximately 2000 in the division who had advanced at dawn. For expediency, the remnants of Hood’s two brigades were reorganized in the field as two regiments. Despite the losses however, these veteran soldiers recovered sufficiently to be used to gather up stragglers from other units. By 1:00 p.m., Hood had been resupplied with ammunition and the men were ready for combat once again, but the main fighting had moved further down the line. The Federals showed no further interest in trying to advance against the Confederate left for the remainder of the day.[8]

After the war, on June 1, 1876, Colonel Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin wrote Colonel (then Governor) Stone a letter that mentioned the fight at Antietam. It reads in part, “We fought the Second Mississippi in the corn field in front of the Dunkark [sic] Church at Antietam. They drove us, and we barely saved by hand a battery of six twelve-pound howitzers, planted in front of some hay stacks. You will remember this place well, if your [sic] are Col. Stone of that Regiment.” This would not be the last time the 2nd Mississippi encountered the 6th Wisconsin in battle. The regiment reported heavy losses of 27 killed and 127 wounded at Antietam. Its strength is not known with certainty, but may have numbered about 300 effectives at the start of the battle (most Southern regiments were much reduced by straggling on the march north into Maryland). Among the wounded were Colonel Stone, Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys and Major John Blair, all the regiment’s field officers.[9]

[1] CMSR.

[2] Johnson and Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders, vol. 2, p. 603; O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 839, 922-923; pt. 2, pp. 609-610; Priest, Before Antietam, p. 218.

[3] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 937; Priest, Antietam, pp. 15-17, 19-23.

[4] Ibid., p. 18. Davis, Leaves in an Autumn Wind, p. 285.

[5] Murfin, Bayonets, p. 210.

[6] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 923, 937.

[7] Priest, Antietam, pp. 52, 55-56, 61-62, 64-65, 68-70; Sears, Landscape, p. 213.

[8] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 925, 938; Sears, Landscape, p. 276.

[9] Rietti, Military Annals of Mississippi, p. 36; Rowland, Military History of Mississippi, p. 47. One of the wounded was the author’s great-grandfather, Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, Company H, 2nd Mississippi. His pension application says he was wounded in both legs on September 17.

South Mountain and Antietam

Major General John Bell Hood

Major General John Bell Hood

Colonel Evander Law The usually cautious McClellan’s newfound sense of aggressiveness was fostered by the discovery on September 13th of a copy of Lee’s campaign plans outlining the division of the Confederate army and routes of march. On September 14th, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Southern forces detached to guard the two passes through South Mountain, Maryland. Responding to the seriousness of the threat, Longstreet ordered Hood back from Hagerstown via Boonsboro to reinforce the Confederate defenders at Turner’s Gap. Immediately upon arriving, Hood deployed Law’s Brigade and his Texans, and in a counterattack, drove the Federals back at bayonet point. The 2nd Mississippi suffered approximately 17-18 casualties, mostly wounded and captured.[1]

Colonel Evander Law The usually cautious McClellan’s newfound sense of aggressiveness was fostered by the discovery on September 13th of a copy of Lee’s campaign plans outlining the division of the Confederate army and routes of march. On September 14th, the Army of the Potomac engaged the Southern forces detached to guard the two passes through South Mountain, Maryland. Responding to the seriousness of the threat, Longstreet ordered Hood back from Hagerstown via Boonsboro to reinforce the Confederate defenders at Turner’s Gap. Immediately upon arriving, Hood deployed Law’s Brigade and his Texans, and in a counterattack, drove the Federals back at bayonet point. The 2nd Mississippi suffered approximately 17-18 casualties, mostly wounded and captured.[1]At nightfall, Lee fell back from the gaps with Hood’s Division acting as rear guard. Although a more prudent commander would have probably fallen back across the Potomac into Virginia, Lee chose to stand and fight. He concentrated his forces in a strong defensive position on the west side of Antietam Creek around the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland. He wanted to maintain this position to block any attempted advance by McClellan and allow time to complete the capture of Harpers Ferry and its garrison.[2]

Tired and hungry, the men of the 2nd Mississippi found it necessary to again advance against the Federals at dusk on the evening of September 16th. Elements of the Army of the Potomac had crossed Antietam Creek north of Lee’s army and were moving into positions opposite the Confederate left flank. Hood was ordered into the East Woods, a small woodlot which was being infiltrated by Federal skirmishers. Law’s Brigade, in skirmish order just north of the East Woods, was suddenly met by a reconnaissance party of the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves (“Bucktails”). The Bucktails, with their Sharps breechloading rifles, used their enhanced firepower to turn the slow withdrawal of Law’s skirmishers into a stampede as they neared the edge of the woods. Luckily, the 4th and 5th Texas arrived to hit the Pennsylvanians simultaneously from the west and south, supported by a section of howitzers from Stephen D. Lee’s artillery battalion. By 8:00 p.m. however, most of Hood’s units had fallen back to the West Woods for the night. As darkness fell, Law’s Brigade soon came under Federal artillery fire from the batteries to their right on the other side of Antietam Creek.[3]

As night approached, the men lay in the West Woods, facing north while the Union heavy guns fired down the length of their lines from the east. Luckily, most of the shots fell just in front or rear of the Confederate positions. However, the colonel of the 11th Mississippi, Phillip Liddell, was struck in the torso by a bursting shell fragment and would die two days later.[4]

Sometime after midnight, Hood’s men were relieved and allowed to get some rest and food. Other than a half ration of beef and some green corn, they had not eaten for three days. As most of the men wearily returned to their original positions near the Dunker Church, details from each company were sent to forage for food and prepare a morning meal.[5]

The men of the 2nd Mississippi were awakened on the morning of September 17th while it was still dark. Although Hood had persuaded General Lee to allow the division to stay in reserve long enough for the men to eat their long-overdue meal, McClellan’s battle plans did not cooperate. Shells began to fall near the Dunker Church in preparation for a Federal assault on the Confederate left. Law was forced to order the still-hungry men to fall into ranks and prepare for battle.[6]

Somewhat after 6:00 a.m., Colonel Law moved his brigade in columns east across the Hagerstown Pike, where it turned north and deployed in a single battle line. The 2nd Mississippi under Colonel Stone anchored the extreme left of Law’s line, while next came the 11th Mississippi, 6th North Carolina and 4th Alabama on the extreme right. To the left of the 2nd Mississippi the Texas Brigade was similarly deployed in line, with the 1st Texas on the right of the brigade. Law’s men advanced into the Miller Cornfield in a generally northerly direction, loading and firing as they went, except for the 4th Alabama, which moved by the right flank down the Smoketown Road toward the East Woods. The veteran fighters of the 2nd and 11th Mississippi and the 6th North Carolina savagely drove the Federals out of the Cornfield (probably upset at having their long-anticipated breakfasts interrupted). They then reformed along a rail fence at the northern edge of the field, continuing to fire at Federal batteries and infantry units coming onto the scene. At one point, the Confederate line rose and fired at a mere thirty feet distance into the 4th and 8th Pennsylvania Reserves, panicking them, which in turn, panicked the 3rd Pennsylvania Reserves in their rear. As the Federals regrouped and additional reinforcements arrived, however, Hood’s men saw they could not continue to hold their position without help. Union soldiers were infiltrating the gap that had developed between the 6th North Carolina’s right flank and the 4th Alabama’s left, slowed by its advance into the East Woods. The men had to fall back. As Law’s men withdrew, the northern border of the Cornfield along the fence was marked by a long precise, row of Mississippians, stuck down where they stood by one terrible fire.[7]

Hood’s punishing counterattack into the Miller Cornfield had saved the Confederate left, but at a terrible cost. As the survivors retired behind the Dunker Church, they found only about 700 unwounded men of approximately 2000 in the division who had advanced at dawn. For expediency, the remnants of Hood’s two brigades were reorganized in the field as two regiments. Despite the losses however, these veteran soldiers recovered sufficiently to be used to gather up stragglers from other units. By 1:00 p.m., Hood had been resupplied with ammunition and the men were ready for combat once again, but the main fighting had moved further down the line. The Federals showed no further interest in trying to advance against the Confederate left for the remainder of the day.[8]

After the war, on June 1, 1876, Colonel Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin wrote Colonel (then Governor) Stone a letter that mentioned the fight at Antietam. It reads in part, “We fought the Second Mississippi in the corn field in front of the Dunkark [sic] Church at Antietam. They drove us, and we barely saved by hand a battery of six twelve-pound howitzers, planted in front of some hay stacks. You will remember this place well, if your [sic] are Col. Stone of that Regiment.” This would not be the last time the 2nd Mississippi encountered the 6th Wisconsin in battle. The regiment reported heavy losses of 27 killed and 127 wounded at Antietam. Its strength is not known with certainty, but may have numbered about 300 effectives at the start of the battle (most Southern regiments were much reduced by straggling on the march north into Maryland). Among the wounded were Colonel Stone, Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys and Major John Blair, all the regiment’s field officers.[9]

[1] CMSR.

[2] Johnson and Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders, vol. 2, p. 603; O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 839, 922-923; pt. 2, pp. 609-610; Priest, Before Antietam, p. 218.

[3] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 937; Priest, Antietam, pp. 15-17, 19-23.

[4] Ibid., p. 18. Davis, Leaves in an Autumn Wind, p. 285.

[5] Murfin, Bayonets, p. 210.

[6] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 923, 937.

[7] Priest, Antietam, pp. 52, 55-56, 61-62, 64-65, 68-70; Sears, Landscape, p. 213.

[8] O.R., 19, pt. 1, pp. 923, 925, 938; Sears, Landscape, p. 276.

[9] Rietti, Military Annals of Mississippi, p. 36; Rowland, Military History of Mississippi, p. 47. One of the wounded was the author’s great-grandfather, Private Thomas Benton Weatherington, Company H, 2nd Mississippi. His pension application says he was wounded in both legs on September 17.

Published on October 05, 2019 12:01

September 20, 2019

Second Manassas

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment:

Second Manassas Following Malvern Hill, Hood’s Division recuperated in the vicinity of Richmond for several weeks. Concluding that Richmond was no longer in danger from McClellan’s forces still on the Peninsula, Lee decided that Major General John Pope, commander of the newly formed Federal Army of Virginia,[1] needed to be “suppressed.” On August 13, 1862, Hood was ordered north to take part in Lee’s new offensive. Lee hoped to strike Pope before the balance of McClellan’s troops could be brought back from the Peninsula as reinforcements. Lee sent Jackson around Pope’s right flank and followed with Longstreet’s command as the Federal commander “took the bait” and moved north in pursuit of Jackson.[2]

After destroying the Federal supply depot at Manassas on August 26th, Jackson established a defensive position along an unfinished railroad cut near the old Manassas battlefield. Pope, after finally locating Jackson, began launching attacks against the position on the evening of August 28th. At about 10:00 a.m. the following day, Lee and Longstreet joined Jackson, while Pope remained oblivious to their presence. Jackson’s men were exhausted and running critically low on ammunition. Longstreet advanced his wing northeasterly along the Warrenton Turnpike, Hood’s Division in the vanguard. Longstreet spent much of the day methodically deploying a massive assault column to smash into Pope’s left flank. Hood positioned his old Texas Brigade to the right of the turnpike and Law to the left. Law’s Brigade thus became the leftmost infantry command in Longstreet’s line, almost, but not quite, linking with Jackson’s right, the gap being covered by Confederate artillery.[3]

About 6:00 p.m. Hood’s men were preparing to conduct a reconnaissance to their front, when two Federal brigades with attached artillery and cavalry, obviously unaware of a Confederate presence, came down the turnpike. Pope, who was convinced that Jackson was in retreat and ignorant of Longsteet’s arrival, had prematurely ordered a pursuit of the supposed retreating Confederates. Hood’s men ambushed the Federal column and pushed them back up the turnpike more than half a mile. At one point a Federal counterattack threatened to throw the Confederates back. Brigadier General Abner Doubleday’s Federal brigade was threatening to turn Law’s right flank.

Law countered this move by aligning the 2nd Mississippi along the road, at right angles to the rest of his line. The Mississippians raked Doubleday’s men with an enfilading fire and forced them to retreat to the top of the ridge. As the Confederates continued to advance and engaged the Federals in the failing light atop the ridge, the fighting degenerated into a confused, bloody brawl. Finally however, the Confederates swept the remaining Union infantry and artillery off the ridge. By this time, only dead and wounded Federals remained. Doubleday’s and Colonel Timothy Sullivan’s (formerly Brigadier General John P. Hatch’s) Federal brigades had become a disorganized mob, heading rearward. Officers rode among the men, trying to rally them in hope that they might at least cover a retreat long enough so that some of the wounded could be brought off.

After unsuccessfully berating several groups of retreating Federal troops, Major Charles Livingston of the 76th New York finally came across a regiment marching, as the Seventy-sixth’s historian put it, “in tolerable order.” Livingston ordered them to halt and turn about, “giving emphasis to the command by earnest gesticulations with his sword, and insisting that it was a shame to see a whole regiment running away.” An officer of the regiment in question, apparently annoyed that a stranger would presume to usurp his command, challenged Livingston: “Who are you sir?”

The reply came back, “Major Livingston of the Seventy-sixth New York.”

“Seventy-sixth what?” asked the officer.

“Seventy-sixth New York.”

“Well, then,” replied the officer, probably with more than a little bemused satisfaction, “you are my prisoner, for you are attempting to rally the Second Mississippi.”[4]

As darkness fell and it was only with difficulty that friend could be distinguished from foe, Hood disengaged and fell back to his original position. By midnight, the 2nd Mississippi was back in line just north of the Warrenton Turnpike near the Brawner Farm.[5]

With the morning of August 30th, Lee awaited Pope’s renewed attacks. However Pope spent the morning arguing with his subordinates that the Confederates were in retreat and not, as was actually the case, massing for a counterstroke. Finally at 3:00 p.m. Porter’s V Corps launched a final attack on Jackson’s position, allowing Longstreet’s artillery to pour a deadly enfilade fire into the left flank of the assault column. The Federal attack swept from southeast to northwest diagonally across the front of Hood’s Division. During this final Federal attack, the men of Hood’s division were essentially just spectators. Finally, Longstreet, seeing that Porter’s attack had been repulsed and that Pope had committed his reserves, sent his own massive assault column of 25,000 gray infantry forward, Hood’s Division in the lead, in a smashing counterattack.[6]

With Hood’s Division designated the “column of direction” for Longstreet’s assault, Law, in theory, was to have advanced on the Texas Brigade’s left flank, just north of the turnpike. Theory had long since fallen victim to dust, death and confusion, however. Law lost contact with the Texans almost immediately. His advance instead amounted to a series of moves from one rise to the next in support of some of Hood’s batteries. By about 5:30 p.m. Law had worked his brigade into position in some timber along Young’s Branch at the base of Dogan Ridge. On the ridge above them, Law’s men could see what was left of Major General Franz Sigel’s Union corps, along with a number of batteries, including Captain Hubert Dilger’s, which had proven to be a particular annoyance to the Southerners during their advance. Law decided to attack. Although successful in putting the 45th New York Infantry Regiment to flight, Law’s pursuit was checked by the 2nd and 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments – Iron Brigade units – backed by artillery. Thinking this was a situation his brigade should not tackle alone, Colonel Law decided to break off the engagement and return to the base of the ridge.[7] The 2nd Mississippi reported losses of 22 killed and 87 wounded for the two days of fighting. Its strength at Second Manassas was not reported, but the regiment may have carried as many as 450-500 men into action.[8]

The beaten Army of Virginia limped back to Washington where it was absorbed into the Army of the Potomac, once more under McClellan’s helm. Lee now decided to take the fight north into Maryland. Potential foreign recognition, fresh recruits from pro-Southern Marylanders, and improved subsistence for the army from Maryland’s unravaged countryside all played a part in the decision to launch his raid. The Army of Northern Virginia left the vicinity of Manassas on September 2nd, crossed the Potomac north of Leesburg, and on September 7th occupied Frederick, Maryland. Lee decided to split his forces in order to capture the large Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry. The bulk of Longstreet’s troops, including the 2nd Mississippi, marched west to Hagerstown while Jackson’s men with assorted other army detachments took various roads south. Shortly after their arrival at Hagerstown, word came that McClellan had left Washington and was uncharacteristically pressing aggressively upon Lee’s rear guard and screening forces.[9]

[1] The army was created by combining the three Federal commands that Jackson had bested during his Shenandoah Valley Campaign – the commands of Shields, Banks and Fremont.

[2] O.R., 11, pt. 3, p. 675; John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run (New York, 1993), pp. 138-139, 144-146, 163.

[3] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 605; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 289-290.

[4] Ibid., pp. 295-296, 298-299. The 2nd Mississippi officer in question was not identified.

[5] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 623; Hennessy, Bull Run, p. 303.

[6] O.R., 12, pt. 2, pp. 565-566; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 339-342, 350-351, 362-365.

[7] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 624; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 425-426; David G. Martin, The Second Bull Run Campaign (Conshohocken, 1997), pp. 246-247.

[8]O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 625. CMSR.

[9] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 839, 922, pt. 2, p. 183, 590-592, 603-604; James V. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets (Baton Rouge, 1965), pp. 88-90; John Michael Priest, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle (New York, 1989), p. xxiii; Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (Boston, 1983), pp. 63-67, 90-92. CMSR. Few new recruits joined the regiment following the spring of 1862.

Second Manassas Following Malvern Hill, Hood’s Division recuperated in the vicinity of Richmond for several weeks. Concluding that Richmond was no longer in danger from McClellan’s forces still on the Peninsula, Lee decided that Major General John Pope, commander of the newly formed Federal Army of Virginia,[1] needed to be “suppressed.” On August 13, 1862, Hood was ordered north to take part in Lee’s new offensive. Lee hoped to strike Pope before the balance of McClellan’s troops could be brought back from the Peninsula as reinforcements. Lee sent Jackson around Pope’s right flank and followed with Longstreet’s command as the Federal commander “took the bait” and moved north in pursuit of Jackson.[2]

After destroying the Federal supply depot at Manassas on August 26th, Jackson established a defensive position along an unfinished railroad cut near the old Manassas battlefield. Pope, after finally locating Jackson, began launching attacks against the position on the evening of August 28th. At about 10:00 a.m. the following day, Lee and Longstreet joined Jackson, while Pope remained oblivious to their presence. Jackson’s men were exhausted and running critically low on ammunition. Longstreet advanced his wing northeasterly along the Warrenton Turnpike, Hood’s Division in the vanguard. Longstreet spent much of the day methodically deploying a massive assault column to smash into Pope’s left flank. Hood positioned his old Texas Brigade to the right of the turnpike and Law to the left. Law’s Brigade thus became the leftmost infantry command in Longstreet’s line, almost, but not quite, linking with Jackson’s right, the gap being covered by Confederate artillery.[3]

About 6:00 p.m. Hood’s men were preparing to conduct a reconnaissance to their front, when two Federal brigades with attached artillery and cavalry, obviously unaware of a Confederate presence, came down the turnpike. Pope, who was convinced that Jackson was in retreat and ignorant of Longsteet’s arrival, had prematurely ordered a pursuit of the supposed retreating Confederates. Hood’s men ambushed the Federal column and pushed them back up the turnpike more than half a mile. At one point a Federal counterattack threatened to throw the Confederates back. Brigadier General Abner Doubleday’s Federal brigade was threatening to turn Law’s right flank.

Law countered this move by aligning the 2nd Mississippi along the road, at right angles to the rest of his line. The Mississippians raked Doubleday’s men with an enfilading fire and forced them to retreat to the top of the ridge. As the Confederates continued to advance and engaged the Federals in the failing light atop the ridge, the fighting degenerated into a confused, bloody brawl. Finally however, the Confederates swept the remaining Union infantry and artillery off the ridge. By this time, only dead and wounded Federals remained. Doubleday’s and Colonel Timothy Sullivan’s (formerly Brigadier General John P. Hatch’s) Federal brigades had become a disorganized mob, heading rearward. Officers rode among the men, trying to rally them in hope that they might at least cover a retreat long enough so that some of the wounded could be brought off.

After unsuccessfully berating several groups of retreating Federal troops, Major Charles Livingston of the 76th New York finally came across a regiment marching, as the Seventy-sixth’s historian put it, “in tolerable order.” Livingston ordered them to halt and turn about, “giving emphasis to the command by earnest gesticulations with his sword, and insisting that it was a shame to see a whole regiment running away.” An officer of the regiment in question, apparently annoyed that a stranger would presume to usurp his command, challenged Livingston: “Who are you sir?”

The reply came back, “Major Livingston of the Seventy-sixth New York.”

“Seventy-sixth what?” asked the officer.

“Seventy-sixth New York.”

“Well, then,” replied the officer, probably with more than a little bemused satisfaction, “you are my prisoner, for you are attempting to rally the Second Mississippi.”[4]

As darkness fell and it was only with difficulty that friend could be distinguished from foe, Hood disengaged and fell back to his original position. By midnight, the 2nd Mississippi was back in line just north of the Warrenton Turnpike near the Brawner Farm.[5]

With the morning of August 30th, Lee awaited Pope’s renewed attacks. However Pope spent the morning arguing with his subordinates that the Confederates were in retreat and not, as was actually the case, massing for a counterstroke. Finally at 3:00 p.m. Porter’s V Corps launched a final attack on Jackson’s position, allowing Longstreet’s artillery to pour a deadly enfilade fire into the left flank of the assault column. The Federal attack swept from southeast to northwest diagonally across the front of Hood’s Division. During this final Federal attack, the men of Hood’s division were essentially just spectators. Finally, Longstreet, seeing that Porter’s attack had been repulsed and that Pope had committed his reserves, sent his own massive assault column of 25,000 gray infantry forward, Hood’s Division in the lead, in a smashing counterattack.[6]

With Hood’s Division designated the “column of direction” for Longstreet’s assault, Law, in theory, was to have advanced on the Texas Brigade’s left flank, just north of the turnpike. Theory had long since fallen victim to dust, death and confusion, however. Law lost contact with the Texans almost immediately. His advance instead amounted to a series of moves from one rise to the next in support of some of Hood’s batteries. By about 5:30 p.m. Law had worked his brigade into position in some timber along Young’s Branch at the base of Dogan Ridge. On the ridge above them, Law’s men could see what was left of Major General Franz Sigel’s Union corps, along with a number of batteries, including Captain Hubert Dilger’s, which had proven to be a particular annoyance to the Southerners during their advance. Law decided to attack. Although successful in putting the 45th New York Infantry Regiment to flight, Law’s pursuit was checked by the 2nd and 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiments – Iron Brigade units – backed by artillery. Thinking this was a situation his brigade should not tackle alone, Colonel Law decided to break off the engagement and return to the base of the ridge.[7] The 2nd Mississippi reported losses of 22 killed and 87 wounded for the two days of fighting. Its strength at Second Manassas was not reported, but the regiment may have carried as many as 450-500 men into action.[8]

The beaten Army of Virginia limped back to Washington where it was absorbed into the Army of the Potomac, once more under McClellan’s helm. Lee now decided to take the fight north into Maryland. Potential foreign recognition, fresh recruits from pro-Southern Marylanders, and improved subsistence for the army from Maryland’s unravaged countryside all played a part in the decision to launch his raid. The Army of Northern Virginia left the vicinity of Manassas on September 2nd, crossed the Potomac north of Leesburg, and on September 7th occupied Frederick, Maryland. Lee decided to split his forces in order to capture the large Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry. The bulk of Longstreet’s troops, including the 2nd Mississippi, marched west to Hagerstown while Jackson’s men with assorted other army detachments took various roads south. Shortly after their arrival at Hagerstown, word came that McClellan had left Washington and was uncharacteristically pressing aggressively upon Lee’s rear guard and screening forces.[9]

[1] The army was created by combining the three Federal commands that Jackson had bested during his Shenandoah Valley Campaign – the commands of Shields, Banks and Fremont.

[2] O.R., 11, pt. 3, p. 675; John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run (New York, 1993), pp. 138-139, 144-146, 163.

[3] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 605; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 289-290.

[4] Ibid., pp. 295-296, 298-299. The 2nd Mississippi officer in question was not identified.

[5] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 623; Hennessy, Bull Run, p. 303.

[6] O.R., 12, pt. 2, pp. 565-566; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 339-342, 350-351, 362-365.

[7] O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 624; Hennessy, Bull Run, pp. 425-426; David G. Martin, The Second Bull Run Campaign (Conshohocken, 1997), pp. 246-247.

[8]O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 625. CMSR.

[9] O.R., 19, pt. 1, p. 839, 922, pt. 2, p. 183, 590-592, 603-604; James V. Murfin, The Gleam of Bayonets (Baton Rouge, 1965), pp. 88-90; John Michael Priest, Antietam: The Soldiers’ Battle (New York, 1989), p. xxiii; Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (Boston, 1983), pp. 63-67, 90-92. CMSR. Few new recruits joined the regiment following the spring of 1862.

Published on September 20, 2019 16:10

September 9, 2019

The Peninsula Campaign: Part II

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment:

The Peninsula Campaign: Part II Shortly after the Battle of Seven Pines, Davis appointed General Robert E. Lee to the command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Stonewall Jackson’s recent smashing victories in the Shenandoah Valley against combined Federal forces three times as large as his own helped shape Lee’s evolving plan to defeat McClellan. Wishing to maintain his options both in the Valley and in front of Richmond, Lee decided he would reinforce Jackson with Chase Whiting’s two brigades. The trip took almost a week. Private Sam Hankins of Company E related a stressful incident during a portion of the trip made by rail:

"At Farmville, Va., we came to the noted long and tall bridge. This bridge had been reported unsafe, and the travelling public between Richmond and Lynchburg would go through Danville, Va., many miles out of the way, to avoid it. We had to risk it, though; and knowing about its being condemned, I had been dreading the danger for some time. I was on top of the car (my usual place) when we arrived at the bridge, and when near its center the train came to a standstill. I looked over the edge of the car far down into the valley, where cattle grazing looked as small as sheep. The engines began to puff and blow and slip, then a slack was followed by a quick jerk, when it seemed that the frail structure was giving way and sinking beneath me. This slacking and jerking lasted one hour, though it appeared to last longer than the war (four years). Conjectures were rife as to the cause of the delay. It was my greatest fright during the war. However, we passed over in safety."[1]

On June 16th, Whiting linked up with Jackson’s “Army of the Valley” at Staunton.[2]

That same day, Lee sent orders to Jackson to join his forces near Richmond. Thus, instead of starting out on another of Jackson’s legendary Valley campaigns, the new arrivals were shocked to learn they were to start back in the direction they had just come. The 2nd Mississippi, first by rail, then on the march, headed toward Richmond now as part of Major General Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Army. Although their destination was the subject of intense speculation, it soon became apparent to the men that Richmond was their goal. The trip to the Shenandoah Valley had only been part of an elaborate ruse.[3]

By June 25th, Jackson gave priority to closing up his strung-out column of march. As a consequence, units of his army in the advance did little more than mark time that day. Sergeant A. L. P. Vairin of the 2nd Mississippi, in the vanguard, recorded, “June 25 Wednesday. Clear. 6 a.m. marched 3 miles & rested til 12 a.m. then marched 1 mi. to Ashland and filed off toward Richmond 1 ½ mi. & rested.... Camped for the night, drew 2 days rations of crackers...”[4]

By June 26th, Jackson’s troops were near the fighting at Mechanicsville between Major General A. P. Hill’s Division and the isolated Federal V Corps commanded by Major General Fitz John Porter. Hill launched a strong attack, but was repulsed with heavy losses. Porter, believing his position to be untenable, retreated to the east.[5]

The Confederates followed Porter the following morning with Jackson’s command on the left wing. Jackson moved with uncharacteristic slowness causing the Confederate battle plans to go awry. A. P. Hill again fell upon the Federals without adequate support. The Union troops were heavily entrenched on high ground behind Boatswain’s Swamp. The battle fought here would carry the name of a nearby landmark called Gaines’ Mill.[6]

Piecemeal attacks against Porter’s center and left had only resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and units being repulsed or pinned down. The rear of the Confederate lines became so chaotic and confused that entire units trying to move forward against the Federals became separated and lost in a sea of human flotsam – wounded and stragglers. Whiting’s Division was the last to arrive on the battlefield. It made its way to a position behind A. P. Hill, just to the right of the Confederate center. As the sun was beginning to fade from view, Lee ordered Whiting forward against the entrenched Federals.[7]

When Colonel Law received the order to advance, he moved out with his brigade in two lines. In the front line was the 11th Mississippi on the left and 4th Alabama on the right. In the rear line was the 2nd Mississippi and 6th North Carolina, respectively. The Texas Brigade formed on Law’s left, also in two lines. Hood’s first line contained, from left to right, Hampton’s Legion, the 5th Texas, and 1st Texas, with the 18th Georgia and 4th Texas in the second line.[8]

After the advance began, General Hood saw that a gap was developing between Law’s right and the left of Brigadier General George E. Pickett’s brigade of Virginians who were moving forward with Law. Hood took personal command of the 4th Texas and maneuvered it across Law’s rear to fill the gap. Apparently some of the men of the 18th Georgia also followed the Texans.[9]

The Federal position chosen as the focus for the attack was a formidable one. Boatswain’s Swamp (actually more of a sluggish stream) flowed at the bottom of a wooded ravine. Behind this stream, the Federals had entrenched in two strong lines, one on the bank of the stream, and the second at the top of the ravine where the woods opened into a field. The stream, with 10-foot banks in places, effectively served as a defensive moat. Earlier the Federals had cleared trees to give them better fields of fire and to construct breastworks, fronted by an abatis of sharpened limbs. To the rear of the second Federal line, the terrain rose to a plateau that was occupied by artillery batteries and additional reserve troops. The Federal troops facing Whiting’s men belonged to Brigadier General John H. Martindales’s Brigade of Brigadier General George W. Morell’s Division, V Corps, Army of the Potomac.[10]

As the 2nd Mississippi advanced with the rest of the brigade, they initially came under artillery fire from the Federal batteries unlimbered on the plateau, but soon were also subjected to heavy musketry. As Whiting reported after the battle:

"...and the whole line, consisting of the Fourth and Fifth Texas, Eighteenth Georgia, Eleventh Mississippi, Fourth Alabama, and Sixth North Carolina, the Second Mississippi being held in partial reserve, but advancing with the line, charged the ravine with a yell, General Hood and Colonel Law gallantly heading [leading] their men."[11]

According to a private in Company E, 2nd Mississippi, the regiment was more involved in the fighting than its “reserve” status would indicate:

"We moved some three or four hundred yards, halted, and came to a front, when Gen. W.C. Whiting, commanding our brigade, gave the order, “Come on!” (not go on). He was seated on his spirited dapple gray. We gave the Rebel yell and across that field we rushed, while men were falling thick and fast. Our orderly sergeant was killed and our second lieutenant wounded. Our third lieutenant being on detached duty, our second sergeant took command of the company."[12]

The charge by Hood’s and Law’s brigades broke the Federal lines and put the defenders to flight, leaving the Confederates in possession of several pieces of artillery, discarded equipment and accouterments and almost two entire Yankee regiments as prisoners of war.[13]

The 2nd Mississippi officially suffered casualties of 21 killed and 79 wounded. It is not known with certainty how many men it took into action. Company E reportedly carried 76 men into the engagement. With its heavy spring recruiting, and accounting for losses at Seven Pines, the regiment may have numbered between 750-800 men during the fight at Gaines’ Mill.[14] “The Second Mississippi, Col. J. M. Stone,” added Whiting in concluding his report of the battle, “was skillfully handled by its commander and sustained severe loss.”[15]

[1] Hankins, Samuel W. “Simple Story of a Soldier,” Nashville: Confederate Veteran, 1912, p. 24.

[2] O.R., 11, pt. 3, p. 594; Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 153.

[3] Ibid., pp. 174-75.

[4] A. L. P. Vairin Diary, June 23-25. Jackson, MS: Department of Archives and History.

[5] O.R., 11, pt. 2, pp. 222, 490-491, 553.

[6] Ibid., p. 492; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 212-213.

[7] O.R., 11, pt. 2, pp. 492-493, 555.

[8] Robert U. Johnson and Clarence C. Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (New York, 1881), vol. 2, p. 363.

[9] O.R., 11, pt. 2, p. 568.

[10] Ibid., pp. 300-302, 306-310; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 213-215.

[11] O.R., 11, pt. 2, p. 563.

[12] Hankins, Simple Story, p. 26.

[13] Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp.240-247.

[14] CMSR.

[15] Ibid., p. 28; O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 565. Following Gaines’ Mill, the Federal commander deceived Lee as to his intended line of retreat. Instead of falling back on his original York River base, McClellan implemented a complex and risky change of base across Lee’s front, south to the James River. Lee however, was never able to firmly come to grips with McClellan’s rear guard and bring the Army of the Potomac to bay on terms favorable to the Confederates. On July 1st, the final battle of the Seven Days, Malvern Hill, was fought. Here the 2nd Mississippi was not actively engaged, but was forced to endure sharpshooter and artillery fire to which they could not effectively reply. The regiment reported losses of 1 killed and 10 wounded, almost all caused by the massed Federal artillery.[1]

At the conclusion of the Seven Days, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia into two “wings” (this was prior to official approval for an army corps organization). These wings were placed under the command of Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet. Although Whiting’s Division had been part of Jackson’s command, it was detached on July 13, 1862, and later assigned to Longstreet’s wing. The division was placed under the command of the senior brigadier, John B. Hood, when Whiting took an extended sick leave from the army. After Whiting was transferred, Hood was given permanent command of the division. The brigade containing the 2nd Mississippi remained under the temporary command of Colonel Law. He was officially promoted to the rank of brigadier general on October 2, 1862.[2]

[1] O.R., 11, pt. 2

[2] O.R., 12, pt. 3, p. 915; Warner, Generals in Gray, p. 175.

The Peninsula Campaign: Part II Shortly after the Battle of Seven Pines, Davis appointed General Robert E. Lee to the command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Stonewall Jackson’s recent smashing victories in the Shenandoah Valley against combined Federal forces three times as large as his own helped shape Lee’s evolving plan to defeat McClellan. Wishing to maintain his options both in the Valley and in front of Richmond, Lee decided he would reinforce Jackson with Chase Whiting’s two brigades. The trip took almost a week. Private Sam Hankins of Company E related a stressful incident during a portion of the trip made by rail:

"At Farmville, Va., we came to the noted long and tall bridge. This bridge had been reported unsafe, and the travelling public between Richmond and Lynchburg would go through Danville, Va., many miles out of the way, to avoid it. We had to risk it, though; and knowing about its being condemned, I had been dreading the danger for some time. I was on top of the car (my usual place) when we arrived at the bridge, and when near its center the train came to a standstill. I looked over the edge of the car far down into the valley, where cattle grazing looked as small as sheep. The engines began to puff and blow and slip, then a slack was followed by a quick jerk, when it seemed that the frail structure was giving way and sinking beneath me. This slacking and jerking lasted one hour, though it appeared to last longer than the war (four years). Conjectures were rife as to the cause of the delay. It was my greatest fright during the war. However, we passed over in safety."[1]

On June 16th, Whiting linked up with Jackson’s “Army of the Valley” at Staunton.[2]

That same day, Lee sent orders to Jackson to join his forces near Richmond. Thus, instead of starting out on another of Jackson’s legendary Valley campaigns, the new arrivals were shocked to learn they were to start back in the direction they had just come. The 2nd Mississippi, first by rail, then on the march, headed toward Richmond now as part of Major General Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Army. Although their destination was the subject of intense speculation, it soon became apparent to the men that Richmond was their goal. The trip to the Shenandoah Valley had only been part of an elaborate ruse.[3]

By June 25th, Jackson gave priority to closing up his strung-out column of march. As a consequence, units of his army in the advance did little more than mark time that day. Sergeant A. L. P. Vairin of the 2nd Mississippi, in the vanguard, recorded, “June 25 Wednesday. Clear. 6 a.m. marched 3 miles & rested til 12 a.m. then marched 1 mi. to Ashland and filed off toward Richmond 1 ½ mi. & rested.... Camped for the night, drew 2 days rations of crackers...”[4]

By June 26th, Jackson’s troops were near the fighting at Mechanicsville between Major General A. P. Hill’s Division and the isolated Federal V Corps commanded by Major General Fitz John Porter. Hill launched a strong attack, but was repulsed with heavy losses. Porter, believing his position to be untenable, retreated to the east.[5]

The Confederates followed Porter the following morning with Jackson’s command on the left wing. Jackson moved with uncharacteristic slowness causing the Confederate battle plans to go awry. A. P. Hill again fell upon the Federals without adequate support. The Union troops were heavily entrenched on high ground behind Boatswain’s Swamp. The battle fought here would carry the name of a nearby landmark called Gaines’ Mill.[6]

Piecemeal attacks against Porter’s center and left had only resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and units being repulsed or pinned down. The rear of the Confederate lines became so chaotic and confused that entire units trying to move forward against the Federals became separated and lost in a sea of human flotsam – wounded and stragglers. Whiting’s Division was the last to arrive on the battlefield. It made its way to a position behind A. P. Hill, just to the right of the Confederate center. As the sun was beginning to fade from view, Lee ordered Whiting forward against the entrenched Federals.[7]

When Colonel Law received the order to advance, he moved out with his brigade in two lines. In the front line was the 11th Mississippi on the left and 4th Alabama on the right. In the rear line was the 2nd Mississippi and 6th North Carolina, respectively. The Texas Brigade formed on Law’s left, also in two lines. Hood’s first line contained, from left to right, Hampton’s Legion, the 5th Texas, and 1st Texas, with the 18th Georgia and 4th Texas in the second line.[8]

After the advance began, General Hood saw that a gap was developing between Law’s right and the left of Brigadier General George E. Pickett’s brigade of Virginians who were moving forward with Law. Hood took personal command of the 4th Texas and maneuvered it across Law’s rear to fill the gap. Apparently some of the men of the 18th Georgia also followed the Texans.[9]

The Federal position chosen as the focus for the attack was a formidable one. Boatswain’s Swamp (actually more of a sluggish stream) flowed at the bottom of a wooded ravine. Behind this stream, the Federals had entrenched in two strong lines, one on the bank of the stream, and the second at the top of the ravine where the woods opened into a field. The stream, with 10-foot banks in places, effectively served as a defensive moat. Earlier the Federals had cleared trees to give them better fields of fire and to construct breastworks, fronted by an abatis of sharpened limbs. To the rear of the second Federal line, the terrain rose to a plateau that was occupied by artillery batteries and additional reserve troops. The Federal troops facing Whiting’s men belonged to Brigadier General John H. Martindales’s Brigade of Brigadier General George W. Morell’s Division, V Corps, Army of the Potomac.[10]

As the 2nd Mississippi advanced with the rest of the brigade, they initially came under artillery fire from the Federal batteries unlimbered on the plateau, but soon were also subjected to heavy musketry. As Whiting reported after the battle:

"...and the whole line, consisting of the Fourth and Fifth Texas, Eighteenth Georgia, Eleventh Mississippi, Fourth Alabama, and Sixth North Carolina, the Second Mississippi being held in partial reserve, but advancing with the line, charged the ravine with a yell, General Hood and Colonel Law gallantly heading [leading] their men."[11]

According to a private in Company E, 2nd Mississippi, the regiment was more involved in the fighting than its “reserve” status would indicate:

"We moved some three or four hundred yards, halted, and came to a front, when Gen. W.C. Whiting, commanding our brigade, gave the order, “Come on!” (not go on). He was seated on his spirited dapple gray. We gave the Rebel yell and across that field we rushed, while men were falling thick and fast. Our orderly sergeant was killed and our second lieutenant wounded. Our third lieutenant being on detached duty, our second sergeant took command of the company."[12]

The charge by Hood’s and Law’s brigades broke the Federal lines and put the defenders to flight, leaving the Confederates in possession of several pieces of artillery, discarded equipment and accouterments and almost two entire Yankee regiments as prisoners of war.[13]

The 2nd Mississippi officially suffered casualties of 21 killed and 79 wounded. It is not known with certainty how many men it took into action. Company E reportedly carried 76 men into the engagement. With its heavy spring recruiting, and accounting for losses at Seven Pines, the regiment may have numbered between 750-800 men during the fight at Gaines’ Mill.[14] “The Second Mississippi, Col. J. M. Stone,” added Whiting in concluding his report of the battle, “was skillfully handled by its commander and sustained severe loss.”[15]

[1] Hankins, Samuel W. “Simple Story of a Soldier,” Nashville: Confederate Veteran, 1912, p. 24.

[2] O.R., 11, pt. 3, p. 594; Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 153.

[3] Ibid., pp. 174-75.

[4] A. L. P. Vairin Diary, June 23-25. Jackson, MS: Department of Archives and History.

[5] O.R., 11, pt. 2, pp. 222, 490-491, 553.

[6] Ibid., p. 492; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 212-213.

[7] O.R., 11, pt. 2, pp. 492-493, 555.

[8] Robert U. Johnson and Clarence C. Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (New York, 1881), vol. 2, p. 363.

[9] O.R., 11, pt. 2, p. 568.

[10] Ibid., pp. 300-302, 306-310; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 213-215.

[11] O.R., 11, pt. 2, p. 563.

[12] Hankins, Simple Story, p. 26.

[13] Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp.240-247.

[14] CMSR.

[15] Ibid., p. 28; O.R., 12, pt. 2, p. 565. Following Gaines’ Mill, the Federal commander deceived Lee as to his intended line of retreat. Instead of falling back on his original York River base, McClellan implemented a complex and risky change of base across Lee’s front, south to the James River. Lee however, was never able to firmly come to grips with McClellan’s rear guard and bring the Army of the Potomac to bay on terms favorable to the Confederates. On July 1st, the final battle of the Seven Days, Malvern Hill, was fought. Here the 2nd Mississippi was not actively engaged, but was forced to endure sharpshooter and artillery fire to which they could not effectively reply. The regiment reported losses of 1 killed and 10 wounded, almost all caused by the massed Federal artillery.[1]

At the conclusion of the Seven Days, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia into two “wings” (this was prior to official approval for an army corps organization). These wings were placed under the command of Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet. Although Whiting’s Division had been part of Jackson’s command, it was detached on July 13, 1862, and later assigned to Longstreet’s wing. The division was placed under the command of the senior brigadier, John B. Hood, when Whiting took an extended sick leave from the army. After Whiting was transferred, Hood was given permanent command of the division. The brigade containing the 2nd Mississippi remained under the temporary command of Colonel Law. He was officially promoted to the rank of brigadier general on October 2, 1862.[2]

[1] O.R., 11, pt. 2

[2] O.R., 12, pt. 3, p. 915; Warner, Generals in Gray, p. 175.

Published on September 09, 2019 17:10

August 31, 2019

The Peninsula Campaign: Part I

A Sketch of the History of the Second Mississippi Infantry Regiment:

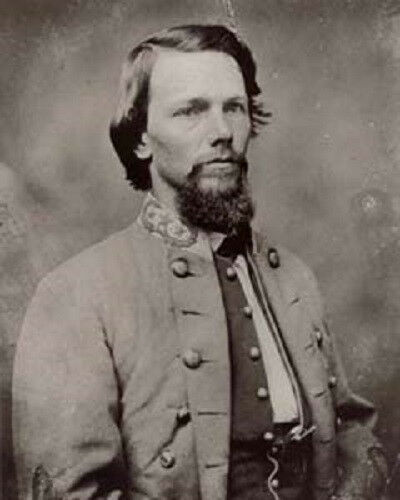

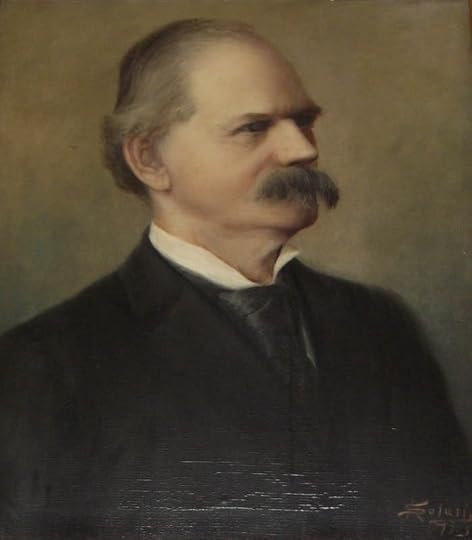

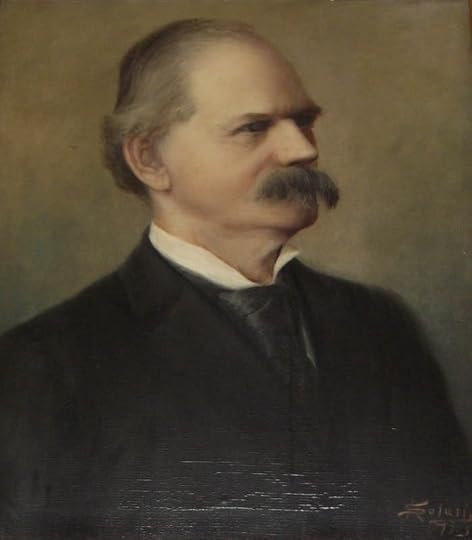

The Peninsula Campaign: Part I Colonel John Marshall Stone. Postwar Portrait General Johnston moved his troops out of winter quarters on March 8, 1862 in reaction to offensive moves by the new Federal commander, Major General George B. McClellan. Through the weekend of March 8th and 9th, the Confederates slipped quietly out of their lines and headed south to Fredericksburg. When the Federal commander later shifted his army by water to Fort Monroe, Johnston responded by moving his troops on April 5th, to Yorktown (of Revolutionary War fame). New recruits joined the 2nd Mississippi’s ranks along the way.[1]

Colonel John Marshall Stone. Postwar Portrait General Johnston moved his troops out of winter quarters on March 8, 1862 in reaction to offensive moves by the new Federal commander, Major General George B. McClellan. Through the weekend of March 8th and 9th, the Confederates slipped quietly out of their lines and headed south to Fredericksburg. When the Federal commander later shifted his army by water to Fort Monroe, Johnston responded by moving his troops on April 5th, to Yorktown (of Revolutionary War fame). New recruits joined the 2nd Mississippi’s ranks along the way.[1]

The regiment spent a relatively quiet month manning the defensive lines at Yorktown. During this time the regiment reorganized “for the war” and on April 23, 1862 installed newly elected officers. Captain John Marshall Stone of Company K, the Iuka Rifles, beat out Colonel Falkner on the second ballot in a close election on April 21st and replaced him in command.[2] In the reorganizations that took place at higher echelons, General Whiting, despite reported problems with alcohol, was assigned to the command of a division that included his old brigade and the Texas Brigade under the command of Brigadier General John Bell Hood. Colonel Evander M. Law of the 4th Alabama assumed command of Whiting’s Brigade.[3]

Johnston, establishing the same pattern of retreat that later became his “trademark,” became fearful that his position at Yorktown would be vulnerable to a turning movement by Union amphibious forces up the York River. This could be expected as soon as McClellan had his heavy artillery in place to suppress the Confederate river batteries. Johnston stayed in the Yorktown defenses only until he thought it prudent to pull out, which he did on May 3rd. He then retreated quickly up the Peninsula toward Richmond with Whiting’s Division acting as the rear guard.[4]

The 2nd Mississippi would see its first major action under Colonel Stone at the Battle of Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks) on May 31, 1862. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had forced Johnston to retreat all the way to the outskirts of Richmond and sat astride the Chickahominy River. Heavy rains caused the river to flood, cutting communications between two Federal corps south of the river and the rest of the Federal army to the north. Johnston hoped to throw his weight against the two isolated Union corps and destroy them. On May 31st, the Confederates advanced along two converging roads toward the enemy positions south of the Chickahominy. Nine Mile Road, the more northerly route, was the one Whiting’s Division was to take. Whiting would be behind and in support of Major General James Longstreet’s Division.[5]

Law’s Brigade advanced on the road toward Seven Pines with the Texas Brigade in the woods to the right. Although the division was originally intended to back up Longstreet’s offensive along Nine Mile Road, Johnston ordered it forward to secure Longstreet’s exposed left flank instead. Law, in the lead, was unexpectedly hit by fire from a long-range enemy battery. Whiting halted the column and deployed Law’s Brigade to meet the artillery threat, but Johnston, insisting the Federals could not be in force this far from Seven Pines, rebuked him for his excessive caution and ordered Law to send a single regiment across the field. The 4th Alabama went forward but was soon put to retreat when a solid line of Federal infantry rose up and fired into their ranks.[6]

At about 2:30 that afternoon, Union Major General Edwin Sumner had pushed Brigadier General John Sedgwick’s division and a battery of his II Corps across the flooded Chickahominy on rickety, makeshift bridges that most other generals would not have dared to use. These troops had met retreating elements of other Federal commands and formed a defensive position northeast of Fair Oaks. Refusing to believe that the Federals could have crossed the swollen Chickahominy in force and anxious to link up with Longstreet, Johnston continued to order piecemeal attacks.[7]

Whiting threw three more brigades into the expanding fight at Fair Oaks, one after another, against a Federal position that was growing steadily stronger as more of Sedgwick’s men came up from the river crossing. By nightfall, the Federals had about 10,700 men in action, a substantial edge over the 8,700 Whiting brought to the fight.[8] During the fighting late in the day, General Johnston was seriously wounded and the senior major general, Gustavus Woodson Smith, suddenly found himself in command of the Confederate army. The battle dragged on the following day, June 1st, and Smith, uncertain of Johnston’s plans and having none of his own, did not inspire confidence when queried by President Jefferson Davis. Davis would allow Smith hold the army’s reins long enough to see the present battle through, but no longer. The army, Davis decided, must have a new commander. The battle ended about 11:30 a.m. that day with little accomplished by either side except a lengthening casualty list. The 2nd Mississippi suffered a total of 37 casualties – 6 killed, 28 wounded (7 mortally), and 4 captured (including one of the wounded).[9]

[1] O.R., 5, p. 529; Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates of Richmond (New York, 1992), pp. 14, 36. Most of the companies of the regiment recruited heavily during February and March of 1862. The threat of being forced into service under the new Conscription Act undoubtedly motivated many men to join up at this time. Additionally, an eleventh company – Company L, composed totally of new recruits – was added to the regiment at this time.

[2] Diary of Major John H. Buchanan, April 21st. Transcribed by Larry J. Mardis, Ph.D. and Jo Anne Ketchum Mardis (Tippah County Historical and Genealogical Society, 1998). Stone won by 445 votes to 410 for Falkner. On the first ballot, Captain Miller also ran. The vote count then was Stone 329, Falkner 302 and Miller 124 [224?].

Stone was born in Gibson County, Tennessee in 1831, but later moved to Corinth, Mississippi where the outbreak of the war found him involved in merchandising. Following the war, he went into politics and was twice elected Governor of the state. In 1876 he was elected by a vote of 97,727 to 47 and in 1889 elected by a vote of 84,929 to 16. He later served as president of the Mississippi Agricultural College. He died on March 26, 1900.

Falkner, apparently bitter over his defeat and not being offered a brigadier general appointment, went back to Mississippi and raised a regiment of cavalry, the 1st Mississippi Partisan Rangers (later renamed the 7th Mississippi Cavalry). He was the colonel of the regiment and served under Chalmers and Forrest. After the war, he built the Gulf & Chicago railroad, became active in politics, and wrote several books. He died on November 7, 1889, having been shot by a business associate in the public square of Ripley, Mississippi (much the same as Colonel Sartoris, his great-grandson’s famous literary character, is also killed).

Hugh R. Miller was a lawyer from Pontotoc prior to the Civil War. He was the Captain of Company G. His discharge papers listed "Superceded" by election as the reason for the discharge and was signed by Governor Pettus. Miller returned to Mississippi and raised a new regiment, the 42nd Mississippi Infantry. Miller and his 42nd Mississippi Volunteer Regiment joined Davis' Brigade during the winter of 1862.

[3] O.R., 11, pt. 2, p. 490; pt. 3, p. 558; Rowland, Mississippi, p. 45.

[4] O.R., 11, pt. 1, p. 275; pt. 3, p. 489; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 59, 66-70.

[5] O.R., 11, pt. 1, pp. 933-934; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 117-119.

[6] O.R., 11, pt. 1, pp. 989-990; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 134-135.

[7] O.R., 11, pt. 1, pp. 763-64, 791; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 135-137.

[8] Ibid., p. 137.

[9] Ibid., pp. 141, 144. CMSR.

The Peninsula Campaign: Part I

Colonel John Marshall Stone. Postwar Portrait General Johnston moved his troops out of winter quarters on March 8, 1862 in reaction to offensive moves by the new Federal commander, Major General George B. McClellan. Through the weekend of March 8th and 9th, the Confederates slipped quietly out of their lines and headed south to Fredericksburg. When the Federal commander later shifted his army by water to Fort Monroe, Johnston responded by moving his troops on April 5th, to Yorktown (of Revolutionary War fame). New recruits joined the 2nd Mississippi’s ranks along the way.[1]

Colonel John Marshall Stone. Postwar Portrait General Johnston moved his troops out of winter quarters on March 8, 1862 in reaction to offensive moves by the new Federal commander, Major General George B. McClellan. Through the weekend of March 8th and 9th, the Confederates slipped quietly out of their lines and headed south to Fredericksburg. When the Federal commander later shifted his army by water to Fort Monroe, Johnston responded by moving his troops on April 5th, to Yorktown (of Revolutionary War fame). New recruits joined the 2nd Mississippi’s ranks along the way.[1]The regiment spent a relatively quiet month manning the defensive lines at Yorktown. During this time the regiment reorganized “for the war” and on April 23, 1862 installed newly elected officers. Captain John Marshall Stone of Company K, the Iuka Rifles, beat out Colonel Falkner on the second ballot in a close election on April 21st and replaced him in command.[2] In the reorganizations that took place at higher echelons, General Whiting, despite reported problems with alcohol, was assigned to the command of a division that included his old brigade and the Texas Brigade under the command of Brigadier General John Bell Hood. Colonel Evander M. Law of the 4th Alabama assumed command of Whiting’s Brigade.[3]