Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 73

August 26, 2023

Book News Week 35

Book News week 35: 28 August – 3 September 2023

Matilda II: The Forgotten Queen

Hardcover – 30 August 2023 (US)

Radegund: The Trials and Triumphs of a Merovingian Queen (WOMEN IN ANTIQUITY)

Paperback – 3 September 2023 (UK)

Elizabeth

Hardcover – 31 August 2023 (UK)

Jane Seymour: An Illustrated Life

Hardcover – 30 August 2023 (UK)

The Forgotten Tudor Royal: Margaret Douglas, Grandmother to King James VI & I

Hardcover – 30 August 2023 (UK)

The Tudors

Paperback – 31 August 2023 (US)

The post Book News Week 35 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 25, 2023

Princess Alexandra the Maccabee – King Herod the Great’s Enemy

Princess Alexandra the Maccabee was one of the “strongest and shrewdest” [1] enemies of King Herod the Great of Judea. She was a Hasmonean princess who constantly schemed against King Herod. As a result, both of her children and her father were killed by King Herod. Thus, Princess Alexandra the Maccabee tried to oust King Herod from the throne and crown herself Queen regnant of Judea. However, her rebellion failed, and she had to suffer heavy consequences.

Princess Alexandra the Maccabee was born in Judea sometime before 63 B.C.E. She was the daughter of King Hyrcanus II of Judea, who briefly reigned for three months until his brother Aristobulus II ousted him from the throne in 66 B.C.E. Her grandmother was Queen regnant Salome Alexandra of Judea. In 55 B.C.E., Princess Alexandra married her cousin, Prince Alexander (the son of King Aristobulus II).[2] She gave birth to two children, Aristobulus and Mariamne. In 49 B.C.E., Prince Alexander was executed by the Romans, and Princess Alexandra became a widow.[3]

When Herod became King of Judea, Princess Alexandra wanted to establish Hasmonean influence in the Herodian court.[4] Therefore, she married her daughter, Mariamne, to King Herod in 37 B.C.E. After Queen Mariamne’s marriage, Princess Alexandra hoped that King Herod would appoint her son, Aristobulus, as the High Priest of Judea.[5] However, King Herod went against her wishes and appointed Hananel as the High Priest instead.[6] Princess Alexandra was outraged and publicly protested against Hananel’s appointment.[7] She wrote to Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and Mark Antony and begged them to help her son become the High Priest.[8]

With the help of Queen Cleopatra and Mark Antony, King Herod had no choice but to appoint Aristobulus as the High Priest in 36 B.C.E.[9] He claimed that the reason why he did not appoint his brother-in-law earlier was because Aristobulus was too young.[10] Shortly after Aristobulus was appointed High Priest, he drowned under mysterious circumstances in King Herod’s winter palace at Jericho.[11] Princess Alexandra believed King Herod murdered her son.[12] She mentioned her suspicions in a letter to Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and Mark Antony.[13] Mark Antony summoned King Herod to explain his side of events.[14] However, King Herod was very charismatic and persuaded Mark Antony that he was innocent.[15]

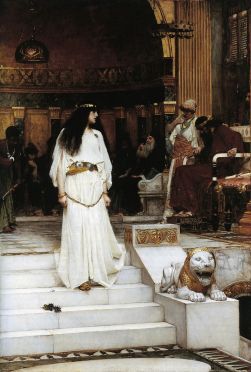

Mariamne Leaving the Judgement Seat of Herod (public domain)

Mariamne Leaving the Judgement Seat of Herod (public domain)After King Herod was deemed innocent, Princess Alexandra tried to escape to Egypt but was caught by King Herod’s men.[16] Princess Alexandra asked her father to ally himself with the King of Nabatea.[17] However, King Herod intercepted her father’s letter to the King of Nabatea and executed him for treason in 30 B.C.E. She even persuaded her daughter, Queen Mariamne, to run away from King Herod.[18] This led to Queen Mariamne’s execution in 29 B.C.E.[19] When Queen Mariamne was sentenced to be executed, Princess Alexandra abandoned her daughter in order to save herself.[20] She called Queen Mariamne a “proud and vile woman” [21] as well as King Herod’s enemy.[22]

After Queen Mariamne was executed, King Herod immediately regretted his decision.[23] He began to grow insane.[24] Princess Alexandra declared that King Herod was unfit to rule and started a rebellion to become the Queen regnant of Judea.[25] She tried to take over Jerusalem by having them surrender the city and the Temple.[26] However, King Herod learned of Princess Alexandra’s rebellion.[27] He captured her and executed her in 28 B.C.E.[28] She died just one year after her daughter.[29]

Princess Alexandra the Maccabee was King Herod’s greatest rival for the throne of Judea. She represented the fallen Hasmonean Dynasty under the new Herodian Dynasty. She was very ambitious and was a constant schemer. She tried to become Queen regnant of Judea but ultimately failed. Thus, all of Princess Alexandra the Maccabee’s plots ended in vain, and it caused her to lose everyone she loved.

Sources:

Ilan, T. (31 December 1999). “Hasmonean Women.” Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved on December 19, 2022 from. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/....

Macurdy, G. H. (1937). Vassal-queens and Some contemporary Women in the Roman Empire. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Milwitzky, W. (1906). “Alexandra”. The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved on December 19, 2022 from https://jewishencyclopedia.com/articl....

[1] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”, para. 1

[2] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[3] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[4] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[5] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[6] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[7] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[8] Macurdy, 1937

[9] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[10] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[11] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[12] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[13] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[14] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[15] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[16] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[17] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[18] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[19] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

[20] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[21] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”, para. 2

[22] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[23] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[24] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[25] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[26] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[27] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[28] Milwitzky, 1906, “Alexandra”

[29] Ilan, 31 December 1999, “Hasmonean Women”

The post Princess Alexandra the Maccabee – King Herod the Great’s Enemy appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 24, 2023

Royal Jewels – Queen Alexandra’s Dagmar Necklace

Queen Alexandra’s Dagmar Necklace was commissioned by King Frederick VII of Denmark for the daughter of his future successor, Princess Alexandra, for her marriage to the then Prince of Wales in 1863.

King Frederick furnished the replica of the Dagmar Cross from the 11th or 12th century with a splinter of wood, supposedly a fragment of the True Cross, with a piece of silk from the grave of King Canute.

Upon the necklace’s arrival in London, it was altered by the jeweller Garrard. The two larger pendant pearls, the central pearl and the diamond cluster, as well as the Dagmar Cross, were made detachable. This allowed Princess Alexandra to wear parts of the necklace separately.

She wore the full piece on at least two occasions when she was dressed as Mary, Queen of Scots, for the Waverley Ball in 1871 and for the coronation in 1902. Queen Alexandra bequeathed the necklace as an heirloom of the Crown on the condition that it wouldn’t be altered.

Embed from Getty ImagesQueen Elizabeth II has worn it with the cross and the two larger pearl pendants detached.1

The post Royal Jewels – Queen Alexandra’s Dagmar Necklace appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 22, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – The early years of King Louis XVI

The future King Louis XVI of France was born on 23 August 1754 as the second surviving son of Maria Josepha of Saxony and Louis, Dauphin of France, who in turn was the elder and only surviving son of King Louis XV of France and Marie Leszczyńska. He was initially titled Duke of Berry, and his older brother was the Duke of Burgundy. Four more younger siblings survived to adulthood, the future King Louis XVIII of France (then known as the Count of Provence), the future King Charles X of France (then known as the Count of Artois) and Princesses Marie Clotilde (later Queen of Sardinia) and Elisabeth.

The future King Louis XVI received the names Louis Auguste from his father, who had named him after Saint Louis, King Louis IX. His mother later told him, “What a King Louis IX was! He was the arbiter of the world. What a saint. He is the patron of your august family and the protector of the monarchy. May you follow in his footsteps.”1 Louis Auguste and his siblings were sometimes referred to as the “Dresden knickknacks”, though only Louis Auguste inherited the fair complexion and bulging blue eyes.2 In his early years, he lived in the shadow of his elder brother, who was adored by their parents.

Until the age of seven, Louis Auguste was in the care of the Countess of Marsan, who also preferred his elder brother as he was the heir. She was also more affectionate towards the Count of Provence. Louis Auguste was later “put in the care of the men”, which meant the Duke de la Vauguyon, the former official playfellow of his father.3 Under the Duke’s supervision, various tutors were employed to undertake Louis Auguste’s education.

By this time, the Duke of Burgundy was seriously ill, and Louis Auguste had started his education early to be a companion for his brother. For seven months, he acted as a companion to his brother, but the Duke of Burgundy ultimately died of tuberculous on 22 March 1761 at the age of nine. This left Louis Auguste as his father’s heir. His parents were devastated by the loss of the Duke of Burgundy. The Dauphin began to closely monitor the education of all the children and personally examined them every Wednesday and Saturday.

Louis Auguste excelled at mathematics, physics and geography. One of his tutors dedicated a book to him and wrote, “…the pleasure you found in the solution of the majority of the problems it contains and the ease with which you grasped the key to their solution are new proofs of your intelligence and the excellence of your judgement…”4 He was 14 years old at that time and was known to be timid and reserved.

The Dauphin would not live to see his son complete his education. He died of tuberculosis on 20 December 1765 at the age of 36. Louis Auguste became the new Dauphin at the age of 11. The youngest sibling, Elisabeth, was not even two years old yet. Their mother, Maria Josepha, went into elaborate mourning and cut off her hair. She commissioned a mausoleum for her husband in the Cathedral at Sens. The Duke de la Vauguyon took the new Dauphin to a portrait of his late father and told him to return to it every day to “meditate before his image” and “propose… one of his virtues to imitate.”5

Maria Josepha also became ill with tuberculosis and died on 14 March 1767 at the age of 35. Young Louis Auguste had just started keeping a diary and wrote, “Death of my mother at eight in the evening.”6 His parents were buried together in the mausoleum Maria Josepha had commissioned for her husband.

The death of Louis Auguste’s parents brought him and his grandfather, King Louis XV, closer together, and they wept in each other’s arms. The King later wrote to the Duke of Parma, “Destiny has given me another son who seems sure to be the happiness of my remaining days; and I love him with all my heart because he returns my love.”7 It certainly helped that Louis Auguste took the initiative to ask to be invited to the hunting suppers organised by the King’s mistress, Madame du Barry.

On 16 May 1770, Louis Auguste married Archduchess Maria Antonia, better known as Marie Antoinette, making her the new Dauphine of France. Despite the rocky start, it was to be a happy marriage. They became King and Queen of France upon the death of Louis Auguste’s grandfather on 10 May 1774. Louis Auguste was still only 19 years old.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – The early years of King Louis XVI appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 21, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – Marie Antoinette & Madame du Barry (Part three)

Just two days after the King’s death, Jeanne was banished to the Abbaye de Pont aux Dames on the orders of the new King. Marie Antoinette wrote to her mother, “Everyone with the name of du Barry has been banished from court.” Even her mother was shocked at her daughter’s behaviour towards an “unfortunate creature who had lost everything and was more in need of pity than anyone else.”1 Upon arrival in the abbey, Jeanne cried out, “How sad it is. Why have they brought me here?”2

The nuns were polite and cold, but they soon warmed up to her. Jeanne stayed with them for two years before she was eventually allowed to move to her beloved Château de Louveciennes. She was glad to be reunited with her sister-in-law Claire, and she had a considerable income. She was surprised by a visit of Marie Antoinette’s brother Joseph II in 1777, who was in France to provide his sister with some marital advice. She showed him the many paintings she had bought but refused the offer of his arm with the words, “Sire, I am not worthy of such an honour.”3 Marie Antoinette was reportedly infuriated that her brother visited her.

During these years, Jeanne fell in love with an Englishman named Henry Seymour, who was married to a French countess, and they became lovers. It all ended rather cruelly when he sent back a miniature of her with the words “Leave me alone” scrawled on it.4 She found another love in the form of the Duke of Brissac, who was proudly calling himself her lover. These were some of the happiest years of her life.

She continued to live an extravagant lifestyle, but she was also quite well known for charitable acts. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who came to paint her portrait, wrote, “I still remember the Countess’s righteous indignation on seeing some poor woman in childbirth who lacked every necessity and two whom the servants had omitted to send the linen and provisions she had ordered. I cannot describe the passion with which she reprimanded the housekeeper while putting together a bundle of the necessary lines, which together with soup and claret was to be taken at once to the poor woman’s cottage.”5

Jeanne stayed at Louveciennes as the revolution began to unfold. In October 1789, Jeanne took care of two wounded officers of the Royal Guard who had come knocking on her door. This would earn her the gratitude of Marie Antoinette but would later be seen as an act of treason by the revolutionary tribunal.

In 1792, the Duke of Brissac was arrested, and he was eventually the victim of a massacre of political prisoners. His head was put on a pike, but Jeanne reportedly fainted before she was able to see it. From October 1792 until early March 1793, Jeanne was in London. She was already listed as an émigré, and her homes were being sealed when she decided to return to France. She told people that she had “a debt of honour to be settled in France.”6 She may not have realised it, but she was signing her own death warrant.

She found her precious Louveciennes under guard but was eventually able to gain it back. One of her servants, Zamor, a Bengali slave, was one of the main instigators in the smear campaign against her. On 22 September 1793, Jeanne was arrested and brought to St Pélagie prison. She would spend two months there, some of it in solitary confinement. It is not known what went through her head when she learned of Marie Antoinette’s execution on 16 October.

On 30 October, two members of the Committee came to examine her, and she managed to avoid incriminating her friends. She did admit to squandering money during her years as a royal mistress. She was supposed to be moved to the La Force prison, but it was overcrowded, and so she remained where she was. On 22 November, she was again submitted to an examination. She later wrote, “I never emigrated, I never even intended doing so. I never provided the émigrés with money.”7

At nine in the morning of 6 December 1793, Jeanne appeared in the Great Hall of Liberty for a trial. Several witnesses testified against her, and the jury returned a guilty verdict the following day. She was condemned to die the next morning. Jeanne fainted upon hearing the verdict. The following morning, she asked for a delay so that she could pass information to the Committee of Public Safety. However, even revealing the location of some of her jewellery would not save her. In the afternoon, the executioner came to cut her hair, and he tied her hands behind her back.

Jeanne’s resolve was broken in the face of death, and she struggled as she was put in the tumbrel. It was already getting darker, and many had been waiting hours to see her die. Upon arrival at the Place de La Révolution, she had to be carried by force as she screamed, “You are going to hurt me! Please don’t hurt me!”8

The guillotine ended her life in seconds, just like it had with Marie Antoinette.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – Marie Antoinette & Madame du Barry (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 20, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – Marie Antoinette & Madame du Barry (Part two)

The court of Versailles was plunged into mourning with the death of Queen Marie on 24 June 1768. Although King Louis XV apparently showed genuine remorse for her death, he was quickly roused from his sorrows by Jeanne. However, she could not be officially introduced at court, and reportedly, Louis was shocked to learn how low-born Jeanne truly was. Her former lover, Jean-Baptiste du Barry, was already married, so he arranged for his brother Guillaume to marry her. They did not meet until the morning of their wedding on 1 September 1768.

King Louis became increasingly dependent on her, but as she had not yet been presented at court, she could not appear with him in public. Meanwhile, Jean-Baptise dispatched his sister Claire to teach Jeanne even more protocol and etiquette. They would become great friends. And although rumours had begun to spread at court that the King was spending most of his time with Jeanne, many did not believe she would actually become his official mistress. Nevertheless, the King brought her back to Versailles to have her officially presented.

She spent a few lonely months at Versailles before someone could be found to present her. The elderly Duchess of Aiguillon, who wanted to have her son back in favour with the King and who just needed some debt paid, was eventually found willing, and she produced the Countess of Béarn to do the deed. On 22 April 1769, Jeanne was officially presented at court. The King had gifted her a court dress and diamonds worth a hundred thousand livres. Even Marie Antoinette’s future husband, the Dauphin, was sufficiently impressed by the radiant and graceful Jeanne that he mentioned it in his diary.

The following day, Jeanne took her place as the King’s official mistress. She was installed in an apartment that the King had direct access to via a staircase. This was the same apartment where Maria Josepha of Saxony, the current Dauphin’s mother, had lived and died, and the move was much criticised by the court. Even being transformed into “Madame du Barry” did not mean she would readily be accepted, and even after her success in conquering the King, many looked down on her.

In the spring of 1770, Jeanne came face to face with Marie Antoinette for the first time. As the Austrian Archduchess travelled to France to marry the Dauphin, Jeanne was invited to the royal supper party at La Muette on 15 May. Dressed in the finest gown she could find, Jeanne spent the evening with most of the royal family as they welcomed Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette asked the Countess of Noailles who she was; the Countess responded that she was there to give the King pleasure. Marie Antoinette then innocently replied, “Oh, then I shall be her rival because I too wish to give pleasure to the King.”1

It wasn’t long before Marie Antoinette learned who Jeanne really was and why she was everywhere at court. Just a few weeks after the wedding, she wrote to her mother, “The King could not be kinder and more full of attentions. I love him dearly, but it is pathetic to see how weak he is with Madame du Barry, who is the silliest and most impertinent creature imaginable. She played cards with us every evening at Marly. Twice she sat beside me, but she never spoke to me, and I made no attempt to speak to her, though when necessary, I have done so.”2 Nevertheless, she received no formal acknowledgement from Marie Antoinette.

The King was initially delighted with the new Dauphine, and soon Marie Antoinette was seen as the one to get rid of the King’s “whore.”3 Nevertheless, Jeanne had a portrait of Marie Antoinette installed in her apartment. The issue of the formal acknowledgement, or lack thereof, grew as Marie Antoinette’s marriage turned out not to be as successful as hoped. Without the proper consummation, Marie Antoinette was in danger of losing the King’s favour. And thus, even her mother urged her to formally acknowledge Jeanne.

Marie Antoinette held out until New Year’s Day 1772. In front of a crowd of courtiers, Marie Antoinette remarked in the general direction of Jeanne, “There are a lot of people here today at Versailles.”4 Afterwards, she vowed never to speak another word to Jeanne. However, during a second encounter, Marie Antoinette once more made conversation in Jeanne’s general direction, much to the King’s delight. Later that evening, Marie Antoinette was showered with the King’s attention.

For the next two years, Jeanne reigned supreme at Versailles, and it was probably for her that King Louis ordered a grand diamond necklace that would later greatly damage Marie Antoinette’s reputation. At the end of April 1774, King Louis began to feel unwell. He was soon transferred back to Versailles, and he wasn’t even fully settled in before he asked for Jeanne to come. As his condition worsened, his daughters cared for him by day, while Jeanne tended to him at night. Soon the first signs of smallpox appeared. Jeanne, who had never had smallpox, stayed by his side, as did his daughters. She even kissed his scarred hands.

Around midnight on 4 May, he told her, “If I had known before what I know now, you would never have been allowed to come to me. From now on, I owe myself to God and to my people. Tomorrow you must leave.[…]You will not be forgotten. Everything that is possible will be done for you.”5 Jeanne knew better than to protest, and she quietly tried to leave the room. However, she fainted on the threshold and had to be carried out. She cried in her room and was brought to the Duke of Aiguillon’s home, where she waited to hear news. King Louis XV of France died on 10 May 1774, making Marie Antoinette and her husband, Louis Auguste, the new King and Queen of France.

Part three coming soon.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – Marie Antoinette & Madame du Barry (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 18, 2023

The Year of Marie Antoinette – Marie Antoinette & Madame du Barry (Part one)

The future Madame du Barry was born Jeanne Bécu on 19 August 1743 as the illegitimate daughter of Anne Bécu. Her father was most likely a monk named Brother Angel or Jean-Baptiste Gomard de Vaubernier.

Jeanne and her mother travelled to Paris with her mother’s lover Monsieur Dumonceaux in 1747, after Anne had given birth to a son named Claude. They initially lived with Anne’s sister Helene, who was the housekeeper to the King’s librarian. Little Claude died just a few months after their arrival in Paris. After this, Monsieur Dumonceaux took Anne and Jeanne home with him, although he lived there with an official mistress named Francesca. Anne worked for them as a cook on the condition that Monsieur Dumonceaux did not go down to the kitchen very often. Francesca was fond of Jeanne and spoiled her.1

With Monsieur Dumonceaux’s help, Anne settled down with a respectable widower by the name of Nicolas Rançon. For Jeanne, this meant that she was now to be educated in the convent of St Aure in the heart of Paris. Although her time there was not the happiest, she eventually realised how much she owed the nuns there. She would spend nine years there and only occasionally received visits from her mother. At the age of 15, she left the convent and returned to live with her mother.

It was her aunt Helene who suggested that Jeanne become a hairdresser’s apprentice, and by the age of 16, she had a job and an employer who was madly in love with her. Her employer, Lametz, was so smitten with her that he allowed her to live in his apartment, and he showered her with gifts. When his mother learned of his infatuation, she raised hell with Jeanne’s mother, Anne, who promptly lodged a complaint for defamation of character. She won the case, and Lametz was forced to sell his business. Around this time, she may have given birth to an illegitimate daughter named Marie Joséphine, who was officially the daughter of Nicolas Rançon.

Jeanne briefly disappears from the records and reappears in 1761 at the age of 18 when she was employed by a rich widow, Madame de la Garde, first as a lady’s maid and then as an official companion. This all fell apart when Jeanne took up her mistress’s two sons, and one of their wives found out and made a scene. But she had now broken into higher society and was taken on as an apprentice at a fashion house run by Monsieur Labille. Although she lived and worked on the premises, weekends were free, and she soon found suitors willing to pay her price. None were long-term, but Jeanne longed for a luxurious life.

Jeanne met Jean-Baptiste, Count du Barry sometime in 1763, although details are a little vague on how both she and her mother came to live with him. Jeanne became his mistress, and he, too, showered her with the finest things in life. Although he was besotted with her, he offered her to the Duke of Richelieu in order to find a place for his son at court. It was the Duke of Richelieu who opened the gates of Versailles for her. As the Count’s mistress, she was an instant hit. An Inspector wrote, “She is a young woman of about nineteen years of age, tall, well-made with a noble carriage and the loveliest of faces. He will certainly try to barter her to his own advantage, for it is what he always does when he begins to tire of a woman.”2 It all ended rather suddenly after a fight, and Jeanne promptly moved out.

She returned after three months and was soon given a new apartment. She gained two new suitors, but the Count also exercised his “rights” by sleeping with her every night. Even the police, who were ever present in observing, noted that “the young lady is overdoing it. She has not the stamina to stand up to this sort of life.”3 From the Count’s son, she began to learn the etiquette of Versailles. In the spring of 1768, she was finally received at Versailles by the Duke of Choiseul.

He was unmoved by her beauty and later wrote, “I found her only moderately pretty. There was a certain awkwardness in her manner, which made me take her for a young woman from the provinces.[..] I was kind, but in order to be rid of her, I passed her on to Monsieur Foulon, who was in charge of that department.”4 On her second visit, she referred to the Count and was recognised as a “kept woman.” Although she had no luck in the office, it was on her way to the state apartments to meet a friend, that she ran into King XV going to mass. Even though the court was gloomy as the Queen was dying, he caught sight of the smiling Jeanne. That same evening, he summoned his valet to find out who she was. It wasn’t too difficult, and Queen Marie was in her last week of life as Jeanne spent her first night with the King.

He later said, “I am delighted by your Jeanne. She is the only woman in France who has managed to make me forget that I am sixty.”5

It would not be long before Jeanne would come face to face with the future Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

Part two coming soon.

The post The Year of Marie Antoinette – Marie Antoinette & Madame du Barry (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 17, 2023

Royal Jewels – The Duchess of Cambridge’s Brooch

The Duchess of Cambridge’s Brooch is a “large pearl bouton encircled by 14 brilliant in cut-down settings and a narrow pave-set cusped band, suspending a brilliant and a large pave-set baroque pearl.”1

Embed from Getty ImagesThe Duchess of Cambridge, born Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, was the original owner of the brooch. Like most of the royal family, she used Garrard as her principal jeweller. She owned some magnificent pieces, and upon her death in 1889, the brooch was inherited by her younger daughter, Princess Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck. Princess Mary Adelaide then passed it to her daughter, the future Queen Mary.

Embed from Getty ImagesQueen Mary wore the brooch for the christenings of the future Queen Elizabeth II and the future King Charles III. It was left to Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. The pearl is detachable, and it has been worn both with and without the pearl.

The post Royal Jewels – The Duchess of Cambridge’s Brooch appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 15, 2023

Book Review: Under the Spell of a Myth: Empress Sisi in Greece by Stefan Haderer

Empress Elisabeth of Austria was well-known for her travels as she wished to spend as little time as possible with her husband in Vienna. One of her favourite destinations was Greece, and she even had a villa named the Achilleion built on Corfu. Unfortunately, she lost interest in the villa a few years before her death. The villa was inherited by her daughter Archduchess Gisela, and it was bought by German Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1907.

Under the Spell of a Myth: Empress Sisi in Greece by Stefan Haderer goes into detail about every trip Elisabeth made to Greece and the Greek readers who accompanied her while there. While largely enjoyable, the level of detail does make it a bit monotonous at times. I also could have done without the biographies of the ten readers, which cover an entire chapter. Nevertheless, you can certainly tell that the author has done his research, and for that, I can only commend him. However, I do not agree with the statement that Elisabeth was obsessed with physical exercise because of her painful joints rather than because of an eating disorder.

Overall, Under the Spell of a Myth: Empress Sisi in Greece by Stefan Haderer is a good book about Empress Elisabeth’s travels to Greece, but this in-depth look may perhaps be a bit much for the casual reader.

Under the Spell of a Myth: Empress Sisi in Greece by Stefan Haderer is available now in the US and the UK.

The post Book Review: Under the Spell of a Myth: Empress Sisi in Greece by Stefan Haderer appeared first on History of Royal Women.

August 13, 2023

Lady Sak K’uk’ – Queen Regnant and mother of the greatest Mayan King

Lady Sak K’uk’ (also known as Queen Muwaan Mat and Lady Beastie) was the second recorded female ruler of the Mayan city of Palenque. She rose to the position of Queen because there were no male candidates who were fit for kingship. In order to legitimise her rule, she declared divinity for herself as a creation goddess. Lady Sak K’uk’ would rule for three years until she abdicated in favour of her son, K’inich Janaab’ Pakal. K’inich Janaab’ Pakal would become known as one of the greatest Mayan Kings.[1]

The birthdate of Lady Sak K’uk’ is unknown. Her name means “Resplendent Quetzal.”[2] Many historians generally believe that she was the daughter of Lady Yohl Ik’nal and Janaab Pakal.[3] However, some historians believe that Lady Yohl Ik’nal may have been her grandmother, and Janaab Pakal may have been either her brother or uncle.[4] King Ajen Yohl Mat may have been her brother.[5] Lady Sak K’uk’ married Kan Mo’ Hix, who was from a noble family.[6] She gave birth to a son named K’inich Janaab’ Pakal.

On 4 April 611 C.E., Palenque was attacked by the Calakmul, who were led by King Scroll Serpent.[7] The Palenque suffered a massive defeat.[8] King Ajen Yohl Mat died sixteen months later, on 8 August 612 C.E. King Ajen Yohl Mat did not name a successor, and there were no male candidates who were suitable to become the next King of the Palenque.[9] The only considerable candidate was Lady Sak K’uk’.[10] Lady Sak K’uk’ was a direct descendant of Lady Yohl Ik’nal, and she had a young son who could succeed her.[11] In order to become Queen of Palenque, she declared divinity on herself as the mother of the maise god.[12]

On 19 October 612 C.E., Lady Sak K’uk’ ascended the throne as the Queen of the Palenque. Her accession name was Queen Muwaan Mat, which meant “Divine Lord of Matwiil.”[13] Events during the reign of Lady Sak K’uk’ remain unknown. She reigned for three years until her son was old enough to rule.[14] On 27 July 615 C.E., Lady Sak K’uk’ formally abdicated as Queen of the Palenque and crowned her son, K’inich Janaab’ Pakal, as the new King of the Palenque.[15] This moment of Lady Sak K’uk’ passing the throne to her son is carved on the Oval Tablet of Palenque.[16] Lady Sak K’uk’ is shown wearing fine jewellery and an ornate shawl and skirt, handing the crown to her son.[17] The coronation was King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal’s favourite moment in his life.[18] Thirty-two years later, he would recall that moment with flawless accuracy.[19]

Even though Lady Sak K’uk’ was no longer Queen regnant, she still wielded political influence on King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal.[20] She died on 12 September 640 C.E. After her death, King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal was worried that his son would not be able to succeed him because he inherited the throne from a woman.[21] Therefore, King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal needed to continue promoting his mother’s divinity.[22] He constructed new buildings and hired artists to carve limestone slabs that depicted Lady Sak K’uk’ as the creation goddess.[23] When his son, Kʼinich Kan Bahlam II, accended the throne as King of the Palenque, no one disputed his rule because he was descended from the creation goddess.[24]

Since it was against tradition for a woman to accend the throne of Palenque, Lady Sak K’uk’ had to declare divinity in order to rule. King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal realised that he had to continue declaring his mother’s divinity in order for his son to succeed him. While very little is known of the reign of Lady Sak K’uk’, it is clear that she was adept at politics and was a capable ruler.[25] She was able to ascend to the throne of Palenque and passed it to her son without any difficulties. Thus, it is clear that Lady Sak K’uk’ was a successful queen.[26] Through King K’inich Janaab’ Pakal’s building projects, the legacy of Lady Sak K’uk’ will continue to live on.[27]

Sources:

Lyons, M. E., Fash, W. L. (2005). The Ancient American World. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Sharer, R. J., Traxler, L. P. (2006). The Ancient Maya (Sixth ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Skidmore, Joel (2010). The Rulers of Palenque (PDF) (Fifth ed.). Mesoweb Publications. Retrieved on 18 December 2022 from https://www.mesoweb.com/palenque/reso....

[1] Skidmore, 2010

[2] Lyons and Fash, 2005, p. 53

[3] Skidmore, 2010

[4] Skidmore, 2010

[5] Sharer, 2006

[6] Sharer, 2006

[7] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[8] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[9] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[10] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[11] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[12] Skidmore, 2010

[13] Skidmore, 2010, p. 67

[14] Sharer, 2006

[15] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[16] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[17] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[18] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[19] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[20] Sharer, 2006

[21] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[22] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[23] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[24] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[25] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[26] Lyons and Fash, 2005

[27] Lyons and Fash, 2005

The post Lady Sak K’uk’ – Queen Regnant and mother of the greatest Mayan King appeared first on History of Royal Women.