Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 59

January 19, 2024

Royal Women at the Dachau concentration camp

The Dachau concentration camp was one of the first concentration camps built by Nazi Germany, and it was initially intended for political opponents. It is located near Munich, and eventually, it also became a place of imprisonment and forced labour for Jews, Romani and other groups. There were around 32,000 documented deaths at the camp, although many may have gone unrecorded. It was liberated by US troops on 29 April 1945.

We know that several royal women were imprisoned at Dachau. The first was Noor Inayat Khan, whose great-great-great-grandfather was Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in South India. Noor served as a Special Operations Executive under the codename Madeleine. In June 1943, she was flown into France, where she was a radio operator. She was betrayed to the Nazis, and she was arrested by the Gestapo in the middle of October 1943. She underwent interrogations and even managed to escape the following month. Unfortunately, she was caught not much later.

She was moved to Pforzheim prison in Germany on the day she was recaptured, and she arrived there on 27 November. She was kept there for months, chained by her hands and feet and kept on the lowest rations. It wasn’t until February of the following year that Noor was allowed to walk outside. Still, the conditions in the prison remained harsh, and time passed slowly.

In September, Noor was discharged from the prison and taken to Karlsruhe, where she would meet the head of the Karlsruhe Gestapo, Josef Gmeiner. In his office, she met three other SOE agents, Elaine Plewman, Madeleine Damerment and Yolande Beekman. Here, the four women were ordered to the Dachau concentration camp, where, unbeknownst to them, the commandant had received the order to execute them. They arrived at midnight on the night of 12/13 September, and the four women were taken to their cells. The former prison of the camp can now be found behind the main, which houses the exhibition about the history of the camp.

For Madeleine, Elaine and Yolande, the end came early the following morning. They were marched from their cell, past the barracks, and they were shot near the crematorium. There are two different versions of Noor’s end. One version states that she was with the three other women. The other version says that Noor was abused for the entire night, being kicked and beaten by German officers in her cell. After being beaten to a bloody mess, the officer became tired of her, ordered her to kneel and put his pistol against her head. She reportedly said, “Liberté” (liberty) just before being executed. All four women’s bodies were burnt in the crematorium, where a memorial plaque in their memories is now placed.1

Click to view slideshow.The other royal women were Princess Irmingard of Bavaria and her sisters, Editha, Hilda, Gabrielle and Sophie, the daughters of Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria and Princess Antonia of Luxembourg. The family of her half-brother Albrecht was also imprisoned with them, so the list also includes his wife, Countess Maria Draskovich de Trakostjan and two daughters, Marie Gabrielle and Marie Charlotte (and their two sons, Franz and Max).

The former royal family of Bavaria (the Kingdom ceased to exist in 1918) had remained relatively safe at the start of the Second World War. When a friend of Crown Prince Rupprecht was arrested and tortured in an attempt to implicate him in treasonous acts against the Nazis, he went into hiding. His only son from his second marriage, Heinrich, went into hiding as well. He had wished for his wife and five daughters to go to a Salvatorean convent, but Princess Antonia feared the heat and believed she would be safe in the Italian Tyrol.

After an assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler’s life in 1944, he went after Antonia and her four youngest daughters as he could not get to Rupprecht. They were arrested, even though Antonia was ill with pleurisy at the time. A doctor tried to delay the orders for Antonia, but her four youngest daughters were taken from her and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Irmingard had managed to evade arrest by going underground near the Austrian border, but she was eventually forced to seek medical help after contracting typhus. In January 1945, she too was taken to Sachensenhausen, where she also encountered her half-brother Albrecht (from her father’s first marriage to Duchess Marie Gabrielle in Bavaria) and his family. Meanwhile, Antonia lingered in a hospital in Innsbruck.

The Russian advance in February 1945 meant that they were all transferred to Flossenbürg concentration camp, where they lived in two crowded rooms as “special” prisoners. From the window, they could see the stacked bodies waiting to be burnt at the crematorium. When Albrecht became seriously ill, the commandant worried what his possible death might mean, and he had the family moved to a forester’s house outside Flossenbürg. While there, they were allowed to take walks, but they were taunted by a guard who showed them pictures of murdered women and children. Irmingar later wrote that she shouted at him, “Tell me, you are in your prime. Why aren’t you at the front defending your beloved Führer? This is a post for old, retired soldiers, isn’t it?”2

When Albrecht had recovered, the family was transferred to the Dachau concentration camp on 8 April. Irmingard had a fainting spell during the transport, and she suspected she was ill with typhus. About Dachau, she wrote, “I started to feel faint again and was supported by a very nice camp doctor. As there was no room in the actual camp, we were housed in the adjoining Red Cross barracks. […] We were still kept apart and couldn’t speak to each other. During the day, we were led around the square in front of the barracks for an hour, always in a circle. Two guards with rifles accompanied us.”3

One of the guards whispered to her that the Americans were close. She later wrote, “It was exciting news that could mean imminent freedom or imminent death.”4

From left to right – Editha, Hilda, Gabrielle, Irmingard, and Sophie with Countess Paula von Bellegarde in May 1945 (public domain)

From left to right – Editha, Hilda, Gabrielle, Irmingard, and Sophie with Countess Paula von Bellegarde in May 1945 (public domain)One final transport brought the family to Ammerwald, where they stayed in an inn. As the US army advanced, the guards began to flee, and eventually, they were freed. Irmingard wrote, “More and more Americans came. They gave us presents of canned food, cigarettes and chocolate. It was hard to believe that we were now liberated and could move around freely.”5

The family was able to reunite with Antonia, who was found emaciated in a hospital near Buchenwald concentration camp. A year later, they were also able to reunite with their father.

Plan your visit to the Dachau concentration camp here.

The post Royal Women at the Dachau concentration camp appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 18, 2024

Catherine of Austria – Grandmother and regent (Part three)

In 1543, the marriage between Maria Manuela and her cousin Philip was settled, which had been one of Catherine’s greatest desires, although it was quite controversial at the Portuguese court. Maria Manuele was second in the line of succession, and it was not outside of the realm of possibilities that she could succeed to the Portuguese throne. Maria Manuela had been brought up by her mother as a model of what a Princess should be, and she had been carefully prepared for her role as Princess of Asturias and future Queen. Dressed in a white satin dress with gold beading and rich jewels, Maria Manuela became the Princess of Asturias. Catherine wore black satin trimmed with velvet.1 She later wrote, “I’m happy to see what I wanted so much completed.”2

Although the ceremony had taken place in March, Maria Manuela did not leave Portugal until October. Catherine said goodbye to her daughter, knowing full well that they would likely never see each other again. Maria Manuela kissed her mother’s hand as she wept during their final farewell. Her father accompanied her part of the way, and it was later written that, “one could clearly see the great love that the King had for the Princess and the great longing he felt for her.”3 Maria Manuela had not even had her first period yet, and she underwent treatments during the early months of her marriage for it. In the summer of 1544, she had her first period, and she fell pregnant just a few months later.

On 8 July 1545, Catherine became a grandmother when Maria Manuela gave birth to a son named Carlos. Everything seemed to have gone well, but Maria Manuela soon became ill with puerperal fever. She was bled several times in an attempt to save her life. One observer reported that “one would say they had bled her to the last drop.”4 Maria Manuela died on 12 July 1545 as the nation celebrated the birth of an heir. The eight-year-old John was now Catherine’s only living child.

John was a sickly child who was often treated with bloodletting, which served to weaken him further. In his infancy, it was feared he was deaf and mute, as he could not speak at the age of three. However, all hope was now vested in him, and his parents fretted over him. With his sister’s marriage to Spain’s heir, Philip, John’s own marriage was also settled. He would, in due time, marry Philip’s sister, Joanna. When he was 14 years old, it was decided that the marriage could now take place. On 11 January 1552, the proxy wedding took place, and John was given his own establishment. He reportedly fathered an illegitimate daughter during this time.5

After her departure was repeatedly postponed, Joanna finally arrived in October 1552. As a wedding present, Catherine presented her new daughter-in-law with a diamond necklace with a diamond cross and a pearl necklace. Catherine and Joanna appeared to be getting along, and Joanna “asks her for her opinion and advice in everything.”6 Joanna fulfilled her primary duty almost immediately as she quickly fell pregnant. However, it became clear that John was sick as he was quickly losing weight. This was likely caused by diabetes, which had no treatment. On 31 December, he fell unconscious, and he died on 2 January 1554 at the age of 16.

Just 18 days later, Joanna gave birth to a son with Catherine holding her hand. He was named Sebastian, as he was born on the feast day of Saint Sebastian. It was likely that Joanna was only told of her husband’s death after the delivery. She was devastated and threw herself onto her bed in tears. Catherine had now lost all of her children, although her new grandson now represented the future of the monarchy. He was baptised eight days after his birth, and Catherine was one of his godparents.

Just three months later, Joanna was recalled to Spain to act as regent for her brother Philip, as he would be travelling to England to be married to Queen Mary I of England. Catherine and Manuel only gave their consent to this on the condition that she would return to Portugal when Philip returned to Spain. However, Joanna never returned to Portugal, and she never saw her son again.

In 1555, Catherine also lost her mother, who had been incarcerated at Tordesillas for many years. Catherine, who had shared her captivity until her marriage, had not seen her mother since. Contact between the two had gone mostly through official channels and via family members, although she did not often discuss her mother with her brother Charles. Upon her mother’s death, she told the Portuguese ambassador in Spain to express her great sorrow.7 The following years would also see the deaths of her brother Charles, and her sisters Mary and Eleanor. This left just Catherine and Ferdinand as the surviving siblings, as Isabella had died in 1526.

However, the death of her husband, King John III, would have the most impact on Catherine’s life. He died on 11 June 1557 at the age of 55. With all their children dead, the crown passed to their grandson Sebastian, who was just three years old. Catherine was with him when John and she closed his eyes and covered him with a sheet. During her husband’s illness, Catherine had already been taking a more active political role, and she was appointed as regent for her grandson with the assistance of her brother-in-law Henry, who was a Cardinal. Catherine did not attend his enthronement ceremony, which took place on 16 June.

Sebastian’s mother also made a claim for the regency from Spain, but she was vetoed by Charles V, who was in the last year of his life. Together with Catherine, he was in secret negotiations to position Maria Manuala’s son Carlos as Sebastian’s heir if he were to die childless. This seems to explain his veto of Joanna as regent.

Part four coming soon.

The post Catherine of Austria – Grandmother and regent (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 17, 2024

Princess Claire at 50

Princess Claire of Belgium was born Claire Louise Coombs on 18 January 1974 as the daughter of Nicholas John Coombs and his Belgian wife, Nicole Eva Gabrielle Thérèse Mertens. She was born in Bath in the United Kingdom. She has an elder sister, Joanna, and a younger brother, Matthew.

When she was just three years old, her family moved to Wavre in Belgium. She attended both primary and secondary school in Wavre. She developed an interest in horse riding, music and painting and was also active in The Guides youth movement. She also sang in the local chair.

After completing her initial schooling, she continued her studies as a surveyor and qualified as a chartered surveyor in 1999.

On 16 December 2002, the engagement between Claire and Prince Laurent of Belgium, the younger brother of King Philippe, was announced. By then, they had been dating for approximately two years.

Embed from Getty ImagesOn 12 April 2003, she married Prince Laurent. By Royal Decree of 1 April 2003, she became a Princess of Belgium. The couple went on to have three children together: Princess Louise (born 2004) and twins Prince Nicolas and Prince Aymeric (born 2005).

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesShe occasionally appears in public alongside her husband to represent the royal family. It was revealed in 2020 that she had suffered from a “lingering illness” about six months before testing positive for COVID-19.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe post Princess Claire at 50 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 16, 2024

Princess’s lost Book of Psalms believed found

Fragments of an almost 1,000-year-old lost manuscript have been uncovered in an archive in the Netherlands, and the manuscript may have belonged to a Princess who fled England.

Thijs Porck, a researcher, identified the 21 fragments found within the binding of a Greek dictionary. Parchment was often recycled to use as binding as it was rather expensive.

Very excited to announce the discovery of Old English fragments inside a series of book bindings! They come from an 11th-c. Latin psalter with Old English glosses and this psalter comes with a fascinating potential backstory involving a refugee English princess!

pic.twitter.com/43a2bT4NOo

— Thijs Porck (@thijsporck) January 11, 2024

The fragments come from a Psalter, and Thijs Porck has dated the fragment to 1050-1075.

“The interlinear Old English gloss makes it a very interesting find because it is relatively rare to find materials in this language,” Porck said. “I could reconstruct some leaves of the Psalter, and, when it was complete, it must have been a beautiful and luxurious book.”

He added, “What made this find even more interesting was the fact that, on the basis of script, language, size and contents, these fragments could be linked to others found throughout Europe: in Cambridge, England; Haarlem, the Netherlands; Sondershausen, Germany; and Elbląg, Poland. These fragments, scattered all over Europe, had once been part of the same manuscript.”

The Psalter may have belonged to a Princess called Gunhild, who had to flee to the continent after the Norman Conquest. She was the sister of King Harold Godwinson, who later died in the Battle of Hastings. She died in exile in Bruges, Belgium, in 1087, after which her belongings were donated to the catholic church in the city. The Psalter was last mentioned in 1561, with added text describing it as the Gunhild Psalter, written in Latin, “but with explanations in the Saxon language, which no one here can quite understand.”

Thijs Porck established that the books of the church were confiscated by Calvinists in 1580, and they sold any books they considered to be unnecessary.

“Perhaps this is how Gunhild’s Psalter ended up in the workshop of a Leiden bookbinder in 1600, and the fragments that were now discovered in Alkmaar may have been part of her personal copy of the Psalms,” Porck said.

The post Princess’s lost Book of Psalms believed found appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Catherine of Austria – Great sorrow (Part two)

Catherine married her first cousin, King John III of Portugal, in the town of Estremoz on 10 February 1525. He was described as a “Prince of medium height, thicker rather than delicate, with a cheerful and authoritative presence.”1 During the religious ceremony, Catherine was described as looking “very handsome” in a white brocade gown with gold fabric and crimson sleeves set with “excellent diamonds.”2 Apparently, the King “had her the first night.”3 After a few days of rest, the newlyweds travelled to Almeirim. However, they likely stayed in Évora until the start of the summer. Catherine wouldn’t see the capital of her new Kingdom, Lisbon, until the beginning of 1527 due to the plague. Even then, it was a short visit as they left again due to yet another outbreak of the plague.

By then, Catherine had given birth to her first child. Just one year after her marriage, Catherine gave birth to a son named Afonso on 24 February 1526. He was baptised on 4 March in the great hall of the Almeirim palace by the bishop of Lamego. Around this time, John’s sister Isabella married Catherine’s brother, Charles, Holy Roman Emperor. Although there was great rejoicing at the birth of a son and heir, it was to be short-lived. He was a sickly infant, and he was born with an abscess on his head. He was moved to Santarém because its higher ground was “healthier for illnesses of the head.”4 He died there in June of that same year. Reportedly, John was resigned to his son’s death “because he went like an angel to paradise,” but Catherine was more visibly grieved.5

Tragically, Catherine and John would lose many more children in the years to come.

On 15 October 1527, Catherine gave birth to a daughter, who was named Maria Manuela. Little Maria Manuela would survive the childhood perils only to die in childbirth at the age of 17. When she was two years old, it was written that “the Princess is very well and their Highnesses are extremely pleased with her, and they are right because she is very beautiful.”6 From an early age, she was promised to her first cousin, the future King Philip II of Spain.

In the early months of 1528, Catherine suffered a miscarriage, which left her very weak. It wasn’t long before she conceived again. Around 11 in the morning on 29 April 1529, Catherine gave birth to another daughter, who was named Isabella. Although there was relief at the birth of a healthy child, there was general disappointment that the child was not a boy. Little Isabella died just a few months later, on 23 July.7 Catherine’s chief chamberlain wrote to Charles, “The Infanta has been taken to heaven by our Lord, and although she was very small, she gave Their Highnesses great sorrow.” In the same letter, it was written that it was already suspected that Catherine was pregnant again.8

Sometime between 30 March and 7 April 1530, Catherine gave birth to another daughter, who was named Beatrice. The little girl was about a month premature. Catherine wrote to her brother that she was “very ill after giving birth, but now I am well.”9 She was again suspected to be pregnant in August 1530, but this was either a false rumour or it ended in a miscarriage. She conceived again around March 1531, but while she was pregnant, Infanta Beatrice died on 1 August 1531 at the age of just 17 months. Catherine wrote to her brother that “it was a pious thing to see her die […] who was so patient and meek.”10 Little Isabella and Beatrice are buried together in the Jerónimos Monastery.

On 1 November 1531, Catherine gave birth to the longed-for male heir. However, he was baptised immediately following birth as he had not cried, and it was believed that he would not live. When the little boy finally appeared to be in the clear, a grand baptism was held, and he received the name Manuel. Catherine’s “pleasure was great at seeing herself give birth to a son, which was the thing in this world she most desired.”11 On 25 March 1533, Catherine gave birth to another son named Philip. The birth of another son, named Dinis, in April 1535 seemed to secure the succession at last. That same year, Manuel was designated as the heir to the throne. Tragically, little Infante Dinis died on 1 January 1537, followed by Manuel on 14 April 1537. Both possibly had epilepsy.

As she laid two of her sons to rest, Catherine was already pregnant again. She gave birth to another son, named John, on 3 June 1537. More tragedy was to come, as Philip died following a bladder disease on 29 April 1539. Catherine had just given birth to another son in March; he was named Antonio. Just a few days later, word reached the Portuguese court that John’s sister Isabella had died in childbirth.

Little Antonio died before his first birthday, leaving John as the “sole and only heir of these kingdoms, on whom their succession and conservation depended.”12 Catherine and her husband were deeply affected by his death “because they could no longer hide it.”13 However, Maria Manuela was also still alive. Catherine was still only 32 years old, but she did not become pregnant again. The Spanish ambassador wrote, “Catherine does everything she can to get pregnant; she hasn’t been pregnant in a year and has already given birth nine times.”14 After a series of treatments of purging and bleeding, Catherine became so faint that the court became alarmed by the state of her health.

Part three coming soon.

The post Catherine of Austria – Great sorrow (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 14, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Margaret of Austria, The pearl of Burgundy (Part three)

Soon, she had built a network of spies around René, and she managed to find evidence of treason, which she presented to her husband. Philibert was shocked, but the evidence was right in front of him. René was immediately relieved of his duties. An armed escort brought René to France, and a return to Savoy would be an immediate death sentence. Margaret wrote to her father, who rescinded René’s earlier legitimisation, and he also banned him from the empire. Margaret could now rule in her husband’s name.

With the right people around her, the castle of Pont d’Ain became the centre of politics. Margaret organised the efficient running of the duchy and made many reforms. Margaret was happy in her new position, but it was not to last. In September 1504, Philibert went hunting on a hot day, and he apparently caught a chill after drinking very cold water. He developed a raging fever, but even the beautiful pearls that Margaret had ground up as medicine could not save him. He died on 10 September 1504 in the very same room he had been born. He was just 24 years old.

Margaret fell into despair and locked herself in her room. Philibert’s heart was removed from his body, and Margaret kept the heart with her at Pont d’Ain. She cut her hair short, and she took to wearing the white hood and black dress of widowhood for the rest of her life. One of her husband’s last wishes was to have a convent built at Brou, and she set out to do that almost immediately. Both Philibert and his mother were eventually buried there. As she and Philibert had no children, Philibert was succeeded in Savoy by his half-brother Charles III. They had never gotten along well, but Margaret was determined to stay in Savoy. Margaret refused a marriage proposal from King Henry VII of England.

In 1506, the news reached her that her brother, Philip, had died. She was one of the few who did not believe that he had been poisoned by his father-in-law, Ferdinand. He left five young children, including his six-year-old heir, Charles. Joanna would give birth to a sixth child the following year. Joanna was considered to be unsuited to reign, although this may have been a narrative conveniently pushed to put her out of power. Joanna’s father, Ferdinand, continued to act as regent in Castile, but the Low Countries and the custody of the children were a different matter. Margaret was chosen as Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands and guardian of Charles. Two of the children, Ferdinand and Catherine, were in Castile, but Eleanor, Mary and Isabella also came into Margaret’s care. On 29 October 1506, Margaret left Pont d’Ain for a new phase in her life.

She arrived in Mechelen on 7 July 1507 after receiving the necessary power to act as Governor. Although she had a difficult start, her governorship was considered to be overall successful. She raised her nephew and nieces with the utmost care, and they came to see her as their “tante and bonne mere” (aunt and good mother).1 Several children from the nobility were also being raised at her court, alongside her nieces and nephew. This included Anne Boleyn, who would marry King Henry VIII of England in 1533.

Margaret knew her power would likely only last as long as Charles was a minor. On 5 January 1515, Charles was officially declared to be of age, a decision which was made without consulting Margaret. Several other issues also plagued her, and she was unjustly blamed for them. After a vigorous defence, Charles declared her to be innocent of any wrongdoing and thanked her for all she had done. However, he did relieve her of all her duties, much to her disappointment. When her father later asked her opinion on something, she replied, “From now on, I won’t get involved in anything anymore.”2 She had been deeply hurt.

Margaret feared having to move out of her residence in Mechelen, but Charles moved his court to Brussels. Eleanor had moved with her brother to Brussels, and she married King Manuel I of Portugal in 1518. Mary was recalled by her grandfather in 1514 to prepare for a marriage to the future King of Hungary. In June 1514, Isabella married King Christian II of Denmark by proxy in Brussels. As her court became more quiet, Margaret threw herself into her books and music.

Slowly but surely, the relationship between Charles and his aunt recovered. Margaret’s father insisted that Charles ask his aunt for advice. When King Ferdinand died in 1516, Charles was declared to be King of Aragon and Castile, and he travelled there in the summer of 1517. He would not return to the Low Countries until May 1520. Margaret was appointed as part of the regency council. The following year, she became the president of the regency council. It would take another year before Charles restored her full powers. In 1519, Charles was also elected as Holy Roman Emperor. Margaret had done a great deal to secure his election, and he thanked her for everything. In 1529, Margaret was part of the so-called Ladies Peace, which determined peace with France alongside her former sister-in-law, Louise of Savoy.

By then, Margaret had grown tired, and her health had declined. She wished to visit Brou one last time to see the progress of the convent, but it was not to be. She had to be carried around in a litter, and she was in a considerable amount of pain. An old wound on her foot had festered, and the infection had spread to the rest of her leg. Gangrene eventually set in, and physicians considered amputating her leg. She continued to work, and on the eve before her death, she was dictating a letter to her nephew. The physicians gave her a dose of opium, hoping to lessen the pain of the amputation. However, she would not wake up again, and she died in the early hours of 1 December 1530.

Her last letter read, “Monseigneur, the hour has come when I can no longer write to you with my own hand, for I feel so ill that I doubt not that my life will be short. With my conscience at rest and peace and resolved to receive all that it may please God to send me, without any regret whatever, excepting the privation of your presence and not being able to see and speak to you once more before my death, which is partly supplied by this my letter, though I fear that it will be the last that you will receive from me. I have named you my universal and sole heir, recommending you to fulfil the charges in my will. I leave you your countries over here, which, during your absence, I have not only kept as you left them to me at your departure but have greatly increased them and restore to you the government of the same, of which I believe to have loyally acquitted myself, in such a way as I hope for divine reward, satisfaction from you, Monseigneur, and the goodwill of your subjects; particularly recommending to you peace, especially with the Kings of France and England. And to end, Monseigneur, I beg of you for the love you have been pleased to bear this poor body, that you will remember the salvation of the soul and the recommendation of my poor vassals and servants. Bidding you the last adieu, to whom I pray, Monseigneur, to give you prosperity and long life. From Malines, the last day of November 1530. Your very humble aunt, Margaret.”3

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Margaret of Austria, The pearl of Burgundy (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

A world without a queen

With the abdication of Queen Margrethe today, the world is now without a reigning queen. It is the first time since the 1800s that the world will be without a woman on a throne.

As such, there’s no one alive who will remember a time when a woman was not a monarch somewhere in the world.

All the thrones in Europe and the world are now taken by men. The current monarchies and their kings are listed below:

Bahrain: King Hamad

Embed from Getty ImagesBelgium – King Philippe

Bhutan: King Jigme Khesar

Brunei: Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah

Cambodia: King Norodom Sihamoni

Denmark: King Frederik X

Photo: Hasse Nielsen ©

Photo: Hasse Nielsen ©Eswatini: King Mswati III

Japan: Emperor Naruhito

Jordan: King Abdullah II

Kuwait: Emir Mishal Al-Ahmad

Lesotho: Letsie III

Liechtenstein: Prince Hans Adam II

Luxembourg: Grand Duke Henri

Malaysia: King Abdullah

Monaco: Prince Albert II

Embed from Getty ImagesMorocco: King Mohammed VI

Norway: King Harald V

Oman: Sultan Haitham bin Tarik

Qatar: Emir Tamim

Saudi Arabia: King Salman

Spain: King Felipe VI

Embed from Getty ImagesSweden: King Carl XVI Gustaf

Thailand: King Rama X

Tonga: King Tupou VI

The Netherlands: King Willem-Alexander

United Arab Emirates: Sheikh Maktoum bin Mohammed

United Kingdom: King Charles III

For some monarchies, women are not allowed to reign; this includes the Arab monarchies and Japan. There is also one European monarchy with those rules – Liechtenstein.

However, the rest of Europe and Bhutan allow for female monarchs; for many of those countries, the future is female.

The Dutch heir – the Princess of Orange Photo: RVD

The Dutch heir – the Princess of Orange Photo: RVDBelgium’s heir is Princess Elisabeth, while the Netherlands’ is Princess Amalia. Princess Ingrid Alexandra is a future monarch for Norway and Crown Princess Victoria for Sweden, and Spain will one day see Princess Leonor on the throne.

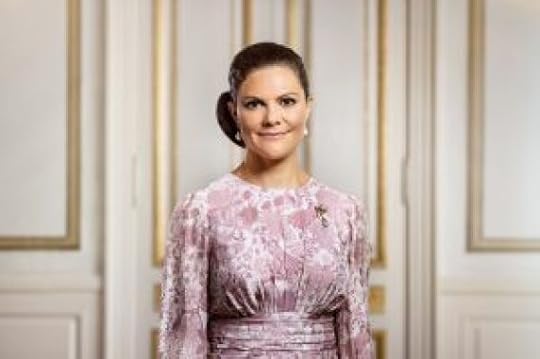

The Swedish heir – Crown Princess Victoria Linda Broström/The Royal Court of Sweden

The Swedish heir – Crown Princess Victoria Linda Broström/The Royal Court of SwedenThe next likely female monarch will be Crown Princess Victoria of Sweden who is the heir to her father, King Carl XVI Gustaf, but the King is in good health, so unless there is another abdication, it could be a while before the world sees a woman on a throne.

The post A world without a queen appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 13, 2024

Catherine of Austria – Her mother’s solace (Part one)

Catherine, or Catalina, of Austria was born on 14 January 1507 as the daughter of Queen Joanna of Castile and King Philip I of Castile, by right of his wife.

Her father had died on 25 September 1506, and she was born as his funeral procession rested in Torquemada for three months. It had been a difficult labour, which nearly cost Joanna her life.1 She was the last of six siblings, but only she and her elder brother Ferdinand were not born in the Low Countries. Her siblings were Eleanor (later Queen of Portugal and France), Charles (later Holy Roman Emperor), Ferdinand (later Holy Roman Emperor), Mary (later Queen of Hungary), and Isabella (later Queen of Denmark). At the time of Catherine’s birth, only Ferdinand lived with them. The others lived with their step-grandmother, Margaret of York. Just four days after her birth, plague struck the town, and one of Joanna’s maidservants died.

Her godparents were Bernardino Fernández de Velasco, 1st Duke of Frías and Diego Ramírez de Villaescusa, Bishop of Málaga, who had supported her in the months after Philip’s death, and her baptism took place at Santa Eulalia. By the spring of 1509, Joanna was being held prisoner at the Royal Palace in Tordesillas by her father due to her supposed mental instability. Catherine’s brother Ferdinand had already been taken from them, and now only Catherine remained with her mother in captivity.

Catherine with her mother at Tordesillas (public domain)

Catherine with her mother at Tordesillas (public domain)Pietro Martire d’Anghiera wrote that Joanna was “secluded of her own accord and always will be while she lives.” 2 He added that she spent her days educating Catherine and busying herself with domestic duties. The reality was probably a bit more horrifying, and there can be no doubt that Joanna was a prisoner. No matter what she did, she would never be allowed to leave.

In 1515, Catherine’s brother Charles was declared to be of age, and the following year, he and their sister Eleanor set out from the Low Countries following the death of their grandfather, King Ferdinand. By then, the two other siblings, Mary and Isabella, were already married. They slowly made their way towards Tordesillas to meet with their mother and the sister they had never met. When Charles met his mother on 4 November 1517, he bowed deep to kiss her hand, but she refused the gesture of respect to embrace them both. They spoke in French throughout, and it was an amicable conversation. She agreed to be co-monarchs with Charles. They did not stay long, and they moved on to Valladolid, where they would meet their brother Ferdinand. Catherine remained with her mother.

Catherine meets her siblings as portrayed in Carlos, Rey Emperador (2015)(Screenshot/Fair Use)

Catherine meets her siblings as portrayed in Carlos, Rey Emperador (2015)(Screenshot/Fair Use)On 13 March 1518, Catherine was secretly moved from Tordesillas by her brother Charles, who wished to include her in his marital discussions. She had been moved through a hole cut in the soft masonry behind a tapestry in the room. She had openly wept “because of her love for the Queen” but was ordered to obey.3 Joanna discovered the hole not much later and immediately went on a hunger and thirst strike. Catherine was returned to her mother two days later. Joanna threatened that if Catherine were taken away, she would “throw herself out of the window or stab herself to death.” 4

The situation at Tordesillas deteriorated under a new regime, and Catherine desperately wrote to her brother that the servants “take everything, use it, and spoil it, so that I have nothing of my own and nothing lasts me.” She also revealed that their mother was also being stolen from and was subjected to severe restraint. She begged Charles to allow their mother to walk for her recreation.5

It would be another six years before Catherine would be allowed to leave her mother. At the end of 1524, she began to prepare for her marriage to King John III of Portugal. They delayed telling Joanna, and the ambassador wrote, “Please God, some vexation will not come from this, although I think that it cannot be prevented because not an hour passes without her wanting to see [Catalina] and asking after her.”6 The marriage contract was signed on 5 July 1524, and Charles stayed at Tordesillas from 3 October to 5 November to form her dowry. Many items were taken without Joanna’s knowledge, and chests with items were moved, only to be returned with different items of a similar weight.

Catherine dressed in cloth of silver for the proxy wedding before reverting quickly back to black to see her mother. Charles left for Madrid, and on 1 January 1525, Catherine finally asked her mother to bless her marriage. The following morning, she ate breakfast, heard mass and made a secretive departure. Joanna was distracted by conversation and only later discovered that Catherine was gone. It was reported that she stood for an entire day and night in the corridor, gazing out of the window and then she “entered her chamber and took to her bed, remaining thus for two days; and no wonder, for this daughter was her solace.”7

Part two coming soon.

The post Catherine of Austria – Her mother’s solace (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Book News Week 3 2024

Book News Week 3 – 15 January – 21 January 2024

Women of the Anarchy

Hardcover – 15 January 2024 (UK)

The post Book News Week 3 2024 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 12, 2024

Meet Princess Josephine of Denmark

Princess Josephine of Denmark was born on 8 January 2011 at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen as the daughter of Crown Prince Frederik and Crown Princess Mary of Denmark. Her twin brother, Vincent, was born 26 minutes earlier.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesShe and Vincent were baptised on 14 April 2011 in Holmen’s Church. Her godparents are Princess Marie of Denmark, Patricia Bailey, Prince Carlo, Duke of Castro, Count Bendt Wedell, Birgitte Handwerk and Josephine Rechner.

She started her official schooling in the 0 class at Tranegårdskolen on 15 August 2017. In 2023, she started in the 6th grade at Kildegård Privatskole.

Embed from Getty ImagesEmbed from Getty ImagesWhen her father becomes King on Sunday, she will be fourth in the line of succession behind her elder siblings.

The post Meet Princess Josephine of Denmark appeared first on History of Royal Women.