Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 53

April 3, 2024

East Wing of Buckingham Palace opens for public tours

The newly reserviced East Wing of Buckingham Palace will be open for public tours for the first time this summer.

Special guided tours will be available for visitors in July and August. In the East Wing, you can find the famous central balcony, where many public appearances have taken place during historic moments.

Click to view slideshow.Small groups will be able to visit the Principal Floor, which has been furnished with highlights from the Royal Collection. This wing was first occupied by Queen Victoria and her family and is still used today for official events. The tour will go through rooms where paintings by Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and Franz Xaver Winterhalter can be seen.

The tour must be booked in addition to the standard admission ticket.

The Summer Opening of the State Rooms at Buckingham Palace is from 11 July to 29 September 2024. The Palace will be open seven days a week during July and August and five days a week during September. The East Wing Highlights Tours will go on sale on 9 April.

The combined ticket price is £75 for Adults. Plan your visit here.

The post East Wing of Buckingham Palace opens for public tours appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 2, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Joan of Portugal, A Queen in an impossible situation (Part three)

It is unclear if the stillbirth of their son caused the relationship between Joan and Henry to deteriorate. However, Joan chose to focus her energy on a marital alliance with Portugal. Sometime in April 1464, her sister-in-law, Isabella, found herself on the way to the Portuguese border to meet with the 31-year-old King Afonso V of Portugal, Joan’s brother. However, this marriage did not take place.

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)Joan’s daughter Joanna was just two years old when a manifesto of complaints and grievances was issued against King Henry by several nobles. This led to the Representation of Burgos in 1464, where Henry was forced to recognise Alfonso as the legitimate heir.1 This was agreed upon with the condition that Alfonso would one day marry Joanna. Beltrán de la Cueva was accused of being a “usurper of royal functions”, while Joanna was “called a Princess, although she is not. […] For it is clear to your Highness that she is not your lordship’s daughter, nor could she succeed or be the heir.”2 Joan herself was, for the first time, publicly accused of adultery. It was later written that while Alfonso lived with her, Joan “had tried many times to kill him with poison,” and she would have succeeded if it had not been for the mayor of the fortress.3

The rebels sent a letter to the nobles of Seville, which also stated Joan’s supposed adultery. It read, “The said Don Enrique (Henry) reached such a great depth of evil that he gave to the traitor Beltrán de la Cueva the Queen Dona Juana (Joan), his wife, so that he could use her at his will. […] Due to the notorious and manifest impotence of the said Enrique to have a generation, which never existed and was never expected to be left by him.”4 Joan’s reputation was being damaged irreperably.

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)However, Henry soon reconsidered, and this led to a ceremonial deposition in effigy in 1465, and the 11-year-old Alfonso was crowned as rival King. Meanwhile, Isabella was still at court with Henry and Joan. Henry ordered Joan to travel to Portugal to enlist the help of her brother, King Afonso V. He also gave her great authority to negotiate, and she left on 6 July 1465. Once more, the focus was on a marriage between her sister-in-law Isabella and her brother, in exchange for military aid. A deal was made on 15 September 1465, which Joan signed in her husband’s name. The marriage would effectively remove Isabella from the political stage. In the end, a truce was proclaimed in October 1465. Meanwhile, Joan’s daughter Joanna was taken in by the Mendoza family.

Since her return from Portugal, “Queen Juana’s prominence was growing. This was a logical consequence of her inclination towards Portugal and her insistence on recognising her daughter as the successor. This increase in her influence displaced some of the nobles, who feared that her intervention would compensate for her husband’s weaknesses.”5

Attacks on Joan continued, and she was accused of corrupting the court with her “seductions.” Although later scholars describe the attacks as limited to superficial aspects of her personality the courtly environment did not differ so much from other European courts.6 In 1466, one of the rebels suggested a marriage with Isabella as the best way to get his family’s loyalty back. In this plan, Isabella was to marry Pedro Girón Acuña Pacheco, who was also 18 years her senior. Henry agreed to the match, but Isabella was horrified as she considered this match to be beneath her dignity. She sank to her knees and began to pray, begging God to free her from the match. As he rode towards the court, he fell ill and died, much to Isabella’s relief. Joan had not openly opposed her husband’s decision, but she had been against the match.7

Isabella prays as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

Isabella prays as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)In 1467, Alfonso triumphantly rode into the city of Segovia, where Joan was living at the time with Alfonso’s sister, Isabella. According to a chronicler, “Queen Joan, who lived in her palace, as soon as she heard the commotion, tried to convince Isabella to go with her, but the Infanta decided to stay. […] When the Queen and Dona Isabella were warned of the proximity of Alfonso’s supporters, Dona Joan, frightened by the great movements, went to the main church, from where she and Beltrán de la Cueva’s wife went to the refuge at the Alcázar.”8

Isabella later wrote, “I stayed in my palace, against the queen’s will, in order to leave her dishonest custody that was bad for my honour and dangerous for my life.”9 She made Alfonso’s counsellors sign a document stating that she would not be forced into marriage before agreeing to come with them. Meanwhile, Joan and her ladies waited at the Alcázar. Henry was later able to enter Segovia peacefully, but he had promised to hand Joan over to Archbishop Alonso de Fonseca y Ulloa. This was part of the agreement Henry had made to be recognised by the rebels.

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)On 30 September 1467, “Queen Joan left her useless husband at the Alcázar and went, as agreed, to the town of Coca.”10 While at the fortress there, Joan learned of the death of her sister Eleanor; she had died following childbirth. Joan was essentially a hostage. She was later moved to Alaejos, and she was allowed to keep just four ladies with her. Henry briefly visited her there.

Part four coming soon.

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Joan of Portugal, A Queen in an impossible situation (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

April 1, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – “She offered us a dead child”

On 19 March 1497, Queen Isabella’s only son, John, married Margaret of Austria in person.

They had to wait two weeks to consummate the marriage as it was Lent. They took to each other immediately, and physicians began to worry about the time the couple spent in bed together. Margaret wrote home to her father how happy she was and that her tears “were not out of sadness.”1 Prince John was “a prisoner to his love for the lady, our young prince is once more too pale.”2 Physicians advised to separate the two from time to time, but Isabella told them that it was not right for man to separate what God has joined.3 And so, John’s health declined at an alarming rate.

On 29 September, Queen Isabella was informed that her son was dangerously ill, and King Ferdinand arrived just in time to say goodbye to his dying son. On 4 October 1497, John died at the age of 20 at the Bishop’s Palace in Salamanca. They had just learned of Margaret’s pregnancy. Isabella devoted herself to looking after Margaret. She and Ferdinand wrote, “Our devotion to the princess only grows, as she tries hard and so sensibly, just as [the person] she is, and we will work to console her and to make her happy as if she had lost nothing. She is healthy with her pregnancy, thank God, and we that – by his Mercy – the fruit that emerges from her will be consolation and repair for our woes. We care and will care for the princess just as if her husband were still alive, for we hold her in that place and love for ever.”4

After a pregnancy of seven months, Margaret went into premature labour. In April 1498, a stillborn daughter was born. One courtier bluntly wrote, “Instead of bearing the much-desired offspring, she offered us a dead child.”5 The chronicler of the Indies wrote, “The sovereigns showed great patience and, as prudent and spirited princes, consoled all [of Spain’s] peoples in writing.”6 Margaret arranged for a grand tomb for her husband and picked from 20 designs. She paid for it from the widow’s gift she received from Castile. The white marble design was eventually placed in Avila. Even decades later, Margaret still paid to have masses said for her late husband’s soul.

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – “She offered us a dead child” appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 31, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Joan of Portugal, A Queen in an impossible situation (Part two)

Rumours concerning the wedding night quickly began to circulate, but Henry headed back on campaign against the Moors just days after his wedding to Joan. He returned on 10 July to find Joan still organising her new household. Just two weeks later, he headed for Seville, and Joan followed him. She was given a grand entry into the city. This grand entry was so costly that it was later criticised. The court remained on the move, as was usual for those days. They were in Ávila when Joan received two pieces of news from her own family.

Her sister-in-law, Isabella of Coimbra, had died at the age of 23 following a “mysterious haemorrhage.”1 A few days later, she learned that her sister Eleanor had given birth to her first child, a son named Christopher, who would tragically die young. And during those early days of their marriage, Henry took Guiomar de Castro as his lover, and she was part of Joan’s household. Another notable figure also made his entrance around this time, Beltrán de la Cueva, who soon became a favourite of the King. It probably wasn’t long before she realised the danger to her own royal position if Henry did not fulfil his duty to her, and by the end of 1458, it was becoming a pressing issue.

The following year, Joan and Guiomar had a fight during which Joan “said very ugly words to her and grabbed her by the hair and struck her on the head and back with a great many blows, and Dona Guiomar shouted so loudly that the King heard them in his chamber where he was already, and he came in great haste.”2

However, the nature of the relationship with Guiomar has been the subject of debate. The King’s secretary wrote that it “had not been verified that [Henry IV] had a union with any other woman, although he closely loved many, both ladies and maidens, of different ages and states, with whom he had secret relations. And he had them continually at home and was with them alone, in remote places, and often made them sleep in his bed, where he confessed that there could never have been carnal copulation with them.”3 Whatever the relationship, after the fight, Henry ordered Guiomar away from the Queen’s household. However, he still went to see her.

By the spring of 1460, a demand was made on Henry – he should declare his half-brother Alfonso his heir until he had descendants of his own. For the first time, the need for Joan to produce an heir was publicly stated. Around this time, Master Samaya, a Jewish physician, was appointed chief physician with a significant salary increase. By July 1461, it appeared that Joanna was pregnant for the first time. But by then, chronicles who had previously praised Joan as a “heroic” example of feminine virtue now accused her of being “obedient to the lustful desires she had resisted for so long.”4 According to Alfonso de Palencia, “all men of sound judgement knew the means used to ensure the Queen’s pregnancy. But no one will say the name of the father.”5

Two main theories surround Joan’s pregnancy. Either she became pregnant with the help of Master Samaya, who used some kind of early form of artificial insemination, or the child was fathered by someone else entirely – named the King’s favourite Beltrán de la Cueva. The artificial insemination theory comes from the diary of a German doctor named Münzer, who was visited decades later. He described the method supposedly used by Master Samaya. “The doctors built a golden cannula, which the Queen inserted to see if she could receive semen through it. They masturbated the King, and sperm came out, but it was watery and sterile.”6

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)Whatever the case, and no matter the ugly rumours, Joan now carried the heir of Castile. As Joan came close to giving birth, Henry wanted any potential challengers for the throne kept close by. His half-siblings, the ten-year-old Isabella and seven-year-old Alfonso, were recalled to court. Isabella later wrote, “Alfonso and I, who were just children at the time, were inhumanely and forcibly torn from our mother’s arms and taken into Queen Juana (Joan)’s power.”7

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)Alfonso and Isabella joined the Queen’s household at the Royal Alcázar of Madrid, where they received a generous clothes allowance. Joan had to endure a very public birth to make sure that the newborn was truly hers, and King Henry was also present in the room. On 28 February 1462, Joan gave birth to a daughter – Joanna. Joan’s young sister-in-law, Isabella, acted as godmother for her newborn niece. Beltrán de la Cueva was granted the title Count of Ledesma a few days after the baptism.

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)Three months later, Henry had Joanna sworn in as the heiress to the throne, and Isabella and her brother Afonso were the first ones to swear. Isabella later claimed that she knew why some nobles said that they had sworn against their will. She wrote, “It was something she [the Queen] had demanded because she knew the truth about her pregnancy and was taking precautions.”8

Nevertheless, the allegations surrounding Joanna’s paternity were the perfect breeding ground for a rebellion. It is impossible to tell if Joanna was Beltrán de la Cueva’s daughter, but we know Joan conceived again within the year and that she was pregnant at the end of December. This was likely the result of a treatment by two Jewish doctors paid for by her brother, the King of Portugal.9 Around mid-March, her pregnancy was announced, but it was not to last. She reportedly lost the child, a boy, after her hair caught fire from a reflected ray of sunshine. However, the news of the death of her sister Catherine could have also contributed. The King was not “only sorry, but disturbed and sad.”10 However, she recovered well, and it was expected that she would conceive again.

Part three coming soon.

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Joan of Portugal, A Queen in an impossible situation (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 30, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Joan of Portugal, A Queen in an impossible situation (Part one)

The future Queen of Castile and sister-in-law to Queen Isabella I of Castile, Joan of Portugal, was born on 31 March 1439 as the daughter of Edward, King of Portugal, and Eleanor of Aragon. Four elder siblings also survived to adulthood: Afonso, King of Portugal, Ferdinand, Duke of Viseu, Eleanor, later Holy Roman Empress, and Catherine. Another sister, Philippa, died of the plague eight days before Joan was born, at the age of eight.

Joan would never know her father as he died of the plague six months before she was born. The custody of her elder brother, now King Afonso V, was taken from her mother and transferred to her uncle Peter, Duke of Coimbra. This deeply affected her mother, who took her daughters to the castle of Almeirim. Her mother continued her attempts to regain the regency and left the castle, leaving Eleanor and Catherine behind. She took Joan with her and even entered Castile, looking for help. It was Joan’s first visit to the country where she would one day be Queen. She even briefly lived under the same roof as her future husband, who was then in the first years of his marriage to the future Queen Blanche II of Navarre.

At the end of February 1442, Queen Eleanor was officially exiled from Portugal. By the end of the summer of 1444, Eleanor and Joan could be found in Toledo. Eleanor was likely already ill by this time as she tried to have her servants placed in other households. She died on 19 February 1445, and although poisoning was suspected, she likely died of natural causes. Joan was just five years old, and she was to be handed over to Vasco de Gouveia, a former servant of her mother. During this time, Joan lived in a monastery in Toledo, “stripped of all her servants and in great misery.”1

Maria of Castile, Queen of Aragon, her aunt by marriage, asked the ambassador to plead with her brother, King John II of Castile, to take care of Joan’s needs and to intervene with the regent of Portugal. She then asked the ambassador to contact the prioress of the monastery to request that Joan be treated with the honour and reverence as befitting her status. She even sent money so that the most immediate needs could be addressed. It is likely that Joan was placed in the monastery to prevent her from being kidnapped. Joan herself seemed most worried about the fate of her mother’s servants as she had written to her aunt about her concerns.

Joan would finally be allowed to return home to Portugal after the marriage of her cousin, Isabella of Portugal, to the widowed King John II of Castile in 1447. She was escorted home by her uncle Peter, Duke of Coimbra, who handed her over to her brother, King Afonso V of Portugal, who had not seen her in seven years. Once she had returned to Lisbon, she went to live in the same household as her sister Catherine, who was 11 years old and received her education alongside her. She learned Latin and subjects such as history and genealogy. In 1451, their eldest sister, Eleanor, left to marry, and soon, Joan’s own marriage was being discussed. After Eleanor left, Catherine and Joan were given their own households.

The Prince of Asturias, the future King Henry IV of Castile, proposed an alliance with Joan, as he wanted to start the process of having his first marriage annulled after many years of childlessness. His stepmother, Isabella, was pregnant and would give birth to the future Queen Isabella I of Castile on 22 April 1451. Henry’s stepmother gave birth to a son named Alfonso in 1453, shortly after the annulment was pronounced due to Henry’s impotence. It even went on to explain that Henry’s impotence did not have a physical cause but had an “evil” cause.2 Blanche was sent home in disgrace. With the marriage plans now going full steam ahead, Joan’s dowry was so large it seemed to imply that the Portuguese knew what they were getting into.

On 13 November 1453, a letter requesting dispensation for marriage, as Joan and Henry were cousins, was sent out. It was granted not much later. However, before the marriage could take place, Henry’s father died at the age of 49, which meant that Henry was now the King of Castile and León. Henry announced that he intended to marry again, and Joan was his intended bride as he heard that “she was a very outstanding woman in graces and beauty.”3

By March 1455, the final preparations for Joan’s departure to Castile were being made, and she left Lisbon sometime in the middle of April. She was accompanied by her brothers and her sister Catherine to a ship that would sail up the Tagus. Along the way, Joan was received with numerous celebrations and received many gifts, such as bull and trout.4 She finally met Henry at Posadas, “about which the Queen was very happy, and the King went to see her and was with her for four or five hours.”5 They had last seen each other when she was still a young child, but now she was a “dazzling beauty.”6

Joan officially entered the city of Córdoba on 20 May, and they were married there in person that same day.7 Following the wedding celebrations, a mass was held on 25 May, after which the consummation would take place. This event had been highly anticipated, but Henry had recently abolished the custom, which required a group of witnesses to be present. According to chronicler Diego de Valera, “At night, the king and queen slept in a bed, and the queen remained as whole as she was, which caused everyone no small irritation.”8

Part two coming soon.

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – Joan of Portugal, A Queen in an impossible situation (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The Alhambra decree

On 31 March 1492, the Alhambra Decree, also known as the Edict of Expulsion, was issued by Queen Isabella I of Castile and her husband, King Ferdinand II of Aragon.

The Jews, who had lived on the Iberian Peninsula since Roman times at least, were considered to be “People of the Book”, a protected status, by Muslims. Since Muslim forces had settled most of the Iberian Peninsula, this allowed the Jewish people to thrive. The Reconquista by the Christians meant that by the 14th century, most of the peninsula had been reconquered.

As the Reconquista came to an end, hostility towards the Jews grew, and many tried to escape the hostility by converting to Christianity. However, not all Christians believed that these conversions were sincere, leading them to be suspicious of the so-called conversos.

Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand had applied to Rome in 1478 to set up an Inquisition in Castile to investigate the conversos and other situations. During the conquest of Granada, Isabella signed the Treaty of Granada with Muhammad XII, known in Europe as Boabdil, to protect the religious freedom of the Muslims there. However, after Granada had been won, the Jews were hated even more than before.

Within three months of the surrender of Granada, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand issued the Alhambra Decree. It stated that they “resolve to order the said Jews and Jewesses of our kingdoms to depart and never to return or come back to them or to any of them. And concerning this we command this our charter to be given, by which we order all Jews and Jewesses of whatever age they may be, who live, reside, and exist in our said kingdoms and lordships, as much those who are natives as those who are not, who by whatever manner or whatever cause have come to live and reside therein, that by the end of the month of July next of the present year, they depart from all of these our said realms and lordships, along with their sons and daughters, menservants and maidservants, Jewish familiars, those who are great as well as the lesser folk, of whatever age they may be, and they shall not dare to return to those places, nor to reside in them, nor to live in any part of them, neither temporarily on the way to somewhere else nor in any other manner, under pain that if they do not perform and comply with this command and should be found in our said kingdom and lordships and should in any manner live in them, they incur the penalty of death and the confiscation of all their possessions by our Chamber of Finance, incurring these penalties by the act itself, without further trial, sentence, or declaration.”1

Queen Isabella, when confronted, claimed this was God’s work. She said, “Do you believe this comes from me? It is the Lord who has put this idea in the king’s heart.”2 The convenient upside of Isabella and Ferdinand’s partnership was that blame could easily be laid on the other.

The Jews were given four months to either leave or convert to Christianity. During this time, they were allowed to sell their goods while under royal protection. Nevertheless, this meant that the Jews became easy targets. The chronicler Andrés Bernáldez wrote, “You and old showed great strength and hope in a prosperous end. But all suffered terrible things; the Christians here acquired a great quantity of their goods, fine houses and estates for very little money, and even though they begged, they could not find people prepared to buy them, exchanging houses for an ass or some vines for a small amount of cloth, since they could not take gold or silver.”3

As Jews departed, checkpoints were set up to make sure they weren’t carrying any gold or silver, and many resorted to swallowing the metals. Many were robbed or killed along the way. Weddings were hurriedly celebrated so that women would not be left unprotected. Rabbi Eliyahu Capsali wrote, “Tens of thousands of Jews converted, and this even included some who were leaving or who had left the country, as they saw what terrible fate awaited them in their travels.”4

They travelled, for example, to the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, or Portugal. A sea journey was particularly perilous, and one exile wrote, “Those who left by the sea found that there was not enough food, and a great number attacked them each day. In some cases, the sailors on the ships tricked them and sold them as slaves. A number were thrown into the sea with the excuse that they were sick [with the plague].”5

Rabbi Eliyahu Capsali later wrote that Isabella “deserved to be known as Jezebel because of the way she did evil in the eyes of God. Isabella always hated the Jews. In this, she was spurred on by the priests, who had persuaded her to hate the Jews passionately.”6

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The Alhambra decree appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Book News Week 14

Book News week 14 – 1 April – 7 April 2024

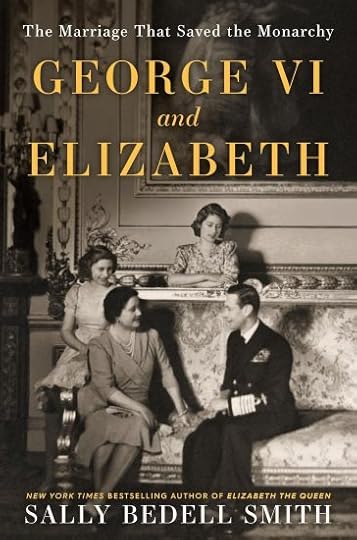

George VI and Elizabeth: The Marriage That Saved the Monarchy

Paperback – 2 April 2024 (US)

The post Book News Week 14 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 28, 2024

The Vladimir Tiara

The Vladimir Tiara is described as follows, “The intersecting brilliant-set circles of the frame are hung with 15 large claw-set pendant pearls, which can be replaced with emerald drops.”1

Embed from Getty ImagesThe tiara was created for Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (born Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin), probably around the time of her marriage to Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia in 1874. It was made by the Russian court jeweller Bolin.

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna wearing the Vladimir tiara (public domain)

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna wearing the Vladimir tiara (public domain)The tiara, along with other jewellery, was smuggled out of Russia during the Russian Revolution by the Grand Duchess’ friend Albert Henry Stopford. In 1921, her daughter, Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, sold some of the jewels, including the tiara, to Queen Mary. It had been damaged during the journey and had to be repaired by the jeweller Garrard. Two of the brilliants were also missing.

Queen Mary wearing the tiara with the emeralds (public domain)

Queen Mary wearing the tiara with the emeralds (public domain)Queen Mary had the tiara adapted in 1924 so that the Cambridge emeralds could also be used. Some of these emeralds had come from the Delhi Durbar tiara.

Queen Elizabeth II inherited the tiara in 1953, and she wore it often. The frame of the tiara was remade entirely in 1988.

The post The Vladimir Tiara appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 26, 2024

Empress Xiaolie – The Empress who was burned to death by her husband

The Jiajing Emperor of the Ming Dynasty had four Empresses. Yet, each of them suffered under his abuse and met a tragic end. One of them was Empress Xiaolie. She was the third Empress of the Jiajing Emperor. Empress Xiaolie saved him from an assassination plot. Yet, the Jiajing Emperor would burn her to death. Empress Xiaolie’s tragic story tells of an Empress who suffered from her abusive husband.

In 1516, Empress Xiaolie was born in Yingtian Prefecture in the Jiangning District (modern-day Nanjing in Jiangsu Province).[1] Her first name is unknown.[2] She was from the Fang family. Her father was Fang Yuezhi, the Marquis of Anping.[3] Her mother’s name is unknown.[4]

In 1534, Lady Fang became a consort of Emperor Jiajing. The Jiajing Emperor and Empress Chen had a strained relationship.[5] He turned his favours to Consort Zhang and Consort Fang.[6] One day in 1528, Consort Zhang Qijie and Consort Fang served tea to the pregnant Empress Chen and the Jiajing Emperor. When the Jiajing Emperor accepted the tea his consorts served him, he stared at them lustfully.[7] Empress Chen was furious when she noticed that the Jiajing Emperor was lusting after other women in her presence.[8] She threw her teacup to the ground and stood up to leave.[9] The Jiajing Emperor was enraged that Empress Chen was displeased with his behaviour.[10] He kicked Empress Chen several times, causing her to have a miscarriage.[11] Empress Chen never recovered and died a month later.[12]

After the death of Empress Chen, the Jiajing Emperor appointed Consort Zhang Qijie as his next Empress. Zhang Qijie was Empress of China for only six years.[13] In 1534, Empress Zhang Qijie interceded for Empress Dowager Zhang’s younger brother, with whom the Jiajing Emperor had a hostile relationship.[14] On 19 January 1534, the Jiajing Emperor deposed Empress Zhang Qijie.[15] He stripped off her crown dress.[16] Then, he whipped her and sent her to the cold palace.[17] The Jiajing Emperor chose Consort Fang to be his next Empress. On 28 January 1534, she was invested as Empress of China.

Empress Fang was said to love rituals and ceremonies.[18] The Jiajing Emperor quickly became tired of her.[19] He was also disappointed that Empress Fang remained childless.[20] He turned his attention to Consort Duan, who would be the love of his life.[21] It was said that the Jiajing Emperor was a cruel man and had many enemies.[22] He would often beat and sexually abuse his palace maids in order to increase his longevity.[23] The palace maids and Concubine Ning were fed up with the Emperor’s abuse.[24] They plotted to kill him.[25]

One night in October 1542, the Jiajing Emperor was sleeping in Consort Duan’s chambers. Consort Duan got out of bed and left the room.[26] As soon as she left, Concubine Ning and fifteen palace maids entered the room to assassinate the sleeping Emperor.[27] They tied a knot with a silken cord and hung it around his neck.[28] Then, they stabbed his groin with their hairpins.[29] Unfortunately, the knot they tied was an overhand.[30] Therefore, it was not tight enough to kill the Jiajing Emperor.[31] Instead, it only left him unconscious.[32]

One of the palace maids panicked when she realized she could not kill the Jiajing Emperor.[33] She ran to Empress Fang’s quarters and notified her of the assassination plot.[34] Empress Fang quickly summoned a physician who saved the Emperor’s life.[35] The Jiajing Emperor remained unconscious for a day and a half.[36] Empress Fang immediately executed all of the women involved in the assassination attempt.[37] In a state of jealousy, Empress Fang also executed Consort Duan (who was not involved in the plot).[38] The assassination attempt became known in history as the Palace Women’s Uprising of Renyin Year.

When the Jiajing Emperor learned that his beloved Consort Duan was executed, he was angry with Empress Fang and never forgave her.[39] In 1547, Empress Fang was trapped in a palace fire. The Jiajing Emperor refused to allow anyone to rescue her.[40] Empress Fang died of her burns.[41] She was thirty-one years old. Even though the Jiajing Emperor allowed her to be burned to death, he gave her an honourable funeral befitting an Empress.[42] This is because he owed her a debt for rescuing him during the Palace Women’s Uprising of Renyin Year.[43] He gave her the posthumous title of Empress Xiaolie, which means “filial martyr.” [44] He also let her be buried alongside him in the Yongling Mausoleum.[45]

Empress Xiaolie’s story is truly tragic. Empress Xiaolie was truly devoted to the Jiajing Emperor. She saved him when he was almost assassinated. Yet, her cruel husband allowed her to be burned to death. Like her two predecessors, it is unfortunate that she met a miserable end at the hands of her abusive husband.

Sources:

Dardess, J. W. (2012). Ming China, 1368-1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire. NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

iNews. (n.d.). “Emperor Jiajing set up three queens in succession, each of them couldn’t end well, and the queens were unbelievable.”. Retrieved on 16 August 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/fd25cd37d....

iNews. (n. d.). “The most famous scumbag emperor in history, as long as the woman who has a relationship with him does not end well.”. Retrieved on 14 August 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/1f8452ac4....

Lin, Y & Lee, L. X. H. trans. (2014). “Chen, Empress of the Jiajing Emperor, Shizong, of Ming.” Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women, Volume II: Tang Through Ming 618 – 1644. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 28-29.

Lin, Y & Lee, L. X. H. trans. (2014). “Fang, Empress of the Jiajing Emperor, Shizong, of Ming.” Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women, Volume II: Tang Through Ming 618 – 1644. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 59-60.

McMahon, K. (2016). Celestial Women: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Song to Qing. NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

[1] Lin and Lee, 2014

[2] Lin and Lee, 2014

[3] Lin and Lee, 2014

[4] Lin and Lee, 2014

[5] Lin and Lee, 2014

[6] Lin and Lee, 2014

[7] Lin and Lee, 2014

[8] iNews, n.d., “Emperor Jiajing set up three queens in succession, each of them couldn’t end well, and the queens were unbelievable.”

[9] Lin and Lee, 2014

[10] iNews, n.d., “Emperor Jiajing set up three queens in succession, each of them couldn’t end well, and the queens were unbelievable.”

[11] iNews, n.d., “Emperor Jiajing set up three queens in succession, each of them couldn’t end well, and the queens were unbelievable.”

[12] Lin and Lee, 2014

[13] iNews, n.d., “Emperor Jiajing set up three queens in succession, each of them couldn’t end well, and the queens were unbelievable.”

[14] iNews, n. d., “The most famous scumbag emperor in history, as long as the woman who has a relationship with him does not end well.”

[15] iNews, n. d., “The most famous scumbag emperor in history, as long as the woman who has a relationship with him does not end well.”

[16] iNews, n. d., “The most famous scumbag emperor in history, as long as the woman who has a relationship with him does not end well.”

[17] iNews, n. d., “The most famous scumbag emperor in history, as long as the woman who has a relationship with him does not end well.”

[18] Lin and Lee, 2014

[19] Lin and Lee, 2014

[20] Dardess, 2012

[21] Lin and Lee, 2014

[22] Lin and Lee, 2014

[23] Lin and Lee, 2014

[24] Lin and Lee, 2014

[25] McMahon, 2016

[26] Lin and Lee, 2014

[27] Lin and Lee, 2014

[28] Lin and Lee, 2014

[29] Lin and Lee, 2014

[30] Lin and Lee, 2014

[31] Lin and Lee, 2014

[32] Lin and Lee, 2014

[33] Lin and Lee, 2014

[34] Lin and Lee, 2014

[35] Lin and Lee, 2014

[36] Lin and Lee, 2014

[37] Lin and Lee, 2014

[38] Lin and Lee, 2014

[39] Lin and Lee, 2014

[40] McMahon, 2016

[41] Lin and Lee, 2014

[42] McMahon, 2016

[43] Lin and Lee, 2014

[44] Lin and Lee, 2014, p. 60

[45] Lin and Lee, 2014

The post Empress Xiaolie – The Empress who was burned to death by her husband appeared first on History of Royal Women.

March 24, 2024

Royal Wedding Recollections – Anne, Prince Royal & William IV, Prince of Orange

On 25 March 1734 (New Style), Anne, Princess Royal, married William IV, Prince of Orange, at St James’s Chapel. Anne was the daughter of George II, King of Great Britain and Caroline of Ansbach.

The marriage was meant to improve the relationship between the Dutch Republic and England, which had been bad since the War of the Spanish Succession. However, William was not seen as a good choice for Anne, and it was written that “whether she would go to bed with this piece of deformity in Holland, or die an ancient maid immured in her royal convent at St James’s […] [Anne] resolved to marry him.” 1 Her mother later said, “The King left her, too, absolutely at liberty to accept or reject it.” 2

Anne and her father had a heart-to-heart, where they could be seen “walking in the garden at Richmond tete a tete… a considerable time, her hand constantly in his, he speaking with great earnestness and seeming affection, and she listening with great emotion and attention, the tears falling so fast all the while that her other hand went every moment to her cheek to wipe them away.” 3 She later said told him that she would “marry him even if he were a baboon.” He responded with, “Well, then, there is baboon enough for you.” 4

Anne had spent much time studying Dutch history and copying works by Titian and Van Dyck from the Royal Collection. Anne walked down the aisle in a wedding dress of stiff blue French silk embroidered with thread. It was lavishly trimmed with ruffles of fine lace and loops of diamonds. She wore her robe of state over it, and her six-foot-train was supported by eight peers’ daughters who were dressed in white and silver.

Around her neck was a magnificent diamond necklace, which had been a gift from her future husband. The ceremony was rather quick, and from Lord Hervey’s memoirs, we learned that the ceremony was “more like the mournful pomp of a sacrifice than the celebration of marriage and put one in mind rather of an Iphigenia leading to the altar than of a bride.” 5 It seemed like a bad start to the marriage.6

Parliament voted for Anne to have a dowry of £80,000.

The post Royal Wedding Recollections – Anne, Prince Royal & William IV, Prince of Orange appeared first on History of Royal Women.