Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 47

June 4, 2024

The Residence – A Wittelsbach Palace

The Residenz, or Residence in Munich, is a former royal palace.

The first building on this site dates from the 14th century and was more of a fortress surrounded by a moat. Construction continued into the 15th century under Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria. The foundation walls and cellar still exist to this day. Over the next four centuries, the Residence developed into an enormous palace with different styles.

The palace suffered immense damage during the Second World War. Most of the rooms were reconstructed, but some of the buildings were rebuilt in a simpler style.

The Hall of Antiquities © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

The Hall of Antiquities © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung(Photo: UIrich Pfeuffer)

www.residenz-muenchen.de

The Ancestral Gallery © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

The Ancestral Gallery © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung(Photo: Toni Schneider)

www.residenz-muenchen.de

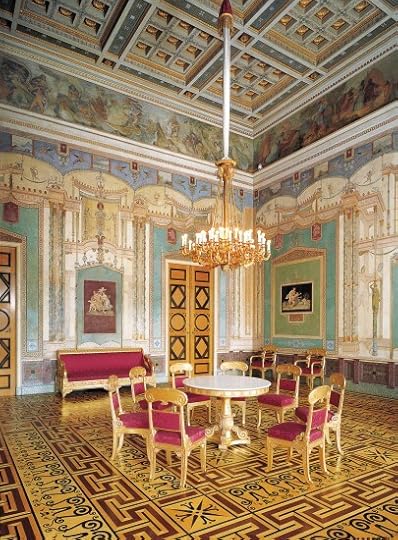

The Queen’s Salon © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung

The Queen’s Salon © Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung(Photo: Maria Custodis/ Andrea Hetzenecker)

www.residenz-muenchen.de

The Residence is currently open to the public, and you’ll need an entire day to visit everything. You can also find the treasury here, which is well worth a visit, with several crowns related to royal women.

Although one can only applaud the reconstruction done after the Second World War, the Residence feels rather grand but lifeless. Information is readily available on signs in German and English; you do not need an audio guide.

In contrast to the grand palace is the absolutely tiny gift shop and ticket desk. This seems like a missed opportunity.

The Residence is easy to reach as public transport stops in front of it.

Plan your visit here.

The post The Residence – A Wittelsbach Palace appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 2, 2024

Empress Chen Jiao – The deposed Empress who practiced witchcraft

Empress Chen Jiao was the first Empress of Emperor Wu of Han. She was Emperor Wu’s childhood sweetheart and first love.[1] Yet, she remained barren and could not give the Emperor a son. She turned into a jealous woman who resorted to witchcraft to eliminate her rival, Wei Zifu, which caused her to be deposed. Empress Chen Jiao’s story has moved poets and writers for over two thousand years.[2] It tells the tale of a promising and happy marriage that slowly deteriorated when she failed to have children.

In 149 B.C.E., Empress Chen Jiao was born. She is also known as Ajiao.[3] She was of imperial descent.[4] Her mother was the Grand Princess Liu Piao. Her maternal grandfather was Emperor Wen. Her maternal grandmother was Empress Dou Yifang. Her father was Chen Wu, the Marquis of Tangyi.

Chen Jiao was childhood playmates with her first cousin, Prince Liu Che (the future Emperor Wu of Han).[5] Legend has it that one day Grand Princess Piao sat Prince Liu Che on her lap and asked him if he wanted a wife.[6] Prince Liu Che pointed at Chen Jiao and said, “If I could have Ajiao as my wife, I would build a house of gold for her.” [7] Even though there are doubts about this legend, Grand Princess Piao did plan the marriage between Chen Jiao and Prince Liu Che.[8] She was also very instrumental in making Prince Liu Che the Crown Prince.[9] Eventually, Chen Jiao married Prince Liu Che.[10] She became his Crown Princess.

On 9 March 141 B.C.E., Liu Che ascended the throne as Emperor Wu of Han. He made her his Empress.[11] They were originally happy, and Empress Chen Jiao was his beloved.[12] However, ten years after Chen Jiao became Empress, she still could not give him any children.[13] Empress Chen Jiao’s barrenness caused her husband to stop visiting her and turn to other women.[14] Empress Chen Jiao became jealous and overbearing, and she gradually lost Emperor Wu’s love.[15] When Emperor Wu of Han favoured Wei Zifu, Empress Chen Jiao was desperate.[16] She tried to win Emperor Wu’s favour by attempting suicide.[17] This only made Emperor Wu angry with her and isolated himself from her.[18] Empress Chen grew more desperate to win Emperor Wu’s favour.[19]

In 130 B.C.E., Empress Chen Jiao hired a witch named Chu Fu to kill Wei Zifu.[20] When Emperor Wu learned that Empress Chen was practising witchcraft, he was enraged.[21] He executed all those who practised sorcery and witchcraft, including Chu Fu and her daughter.[22] This was a total of 300 people who were executed.[23] Emperor Wu did spare his Empress.[24] However, on 20 August 130 B.C.E., Emperor Wu officially deposed Empress Chen Jiao.[25] He stated that her being involved in witchcraft made her unfit to be an Empress.[26] Empress Chen Jiao was forced to give up her imperial seal and ribbon.[27] She was banished to Changmen Palace.[28] He made Wei Zifu his Empress instead.

Even though the deposed Empress Chen Jiao was banished, she did not give up hope of gaining Emperor Wu’s favour.[29] She paid a poet named Sima Xiangru a hundred gold to write a poem expressing her sorrow and grief. This poem is known as “Changmen Fu.” [30] Emperor Wu was so moved by it that he paid her a brief visit.[31] However, he never reinstated her as Empress.[32] The deposed Empress Chen Jiao spent the remainder of her life alone in Changmen Palace, where she died at the age of thirty-nine in 110 B.C.E.[33] She was buried east of Langguan Pavilion in Baling County, which was far from her ancestral cemetery.[34]

Empress Chen Jiao initially had a happy marriage with Emperor Wu. For over ten years, she was his beloved.[35] Yet, her greatest undoing was that she had failed to give Emperor Wu any children.[36] Her barrenness made her insecure and desperate.[37] It caused her to lose the Emperor’s favour, which led her to practice witchcraft and sorcery. If Empress Chen Jiao had given Emperor Wu a son, her story would have been very different. “Changmen Fu” [38] has caused many writers and poets throughout generations to be sympathetic towards Empress Chen Jiao.[39] They would portray her marriage to Emperor Wu as tragic.[40] Her story continues to move the world today.

Sources:

Wang, L. (2015). “Chen Jiao, Empress of Emperor Wu”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 114-115.

iNews. (n.d.). “Chen Ajiao is so proud of being pampered she can’t buy a gift for her daughter to exchange it for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty.”. Retrieved on 9 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/cba283a29....

iNews. (n.d.). “The first queen Emperor Wuxi of the Han Dynasty – cousin Chen Jiao”. Retrieved on 9 October 2023 from https://inf.news/en/history/c972fbd1a....

[1] Wang, 2015

[2] Wang, 2015

[3] Wang, 2015

[4] Wang, 2015

[5] Wang, 2015

[6] Wang, 2015

[7] Wang, 2015, p. 114

[8] iNews, n.d., “The first queen Emperor Wuxi of the Han Dynasty – cousin Chen Jiao”

[9] iNews, n.d., “The first queen Emperor Wuxi of the Han Dynasty – cousin Chen Jiao”

[10] iNews, n.d., “The first queen Emperor Wuxi of the Han Dynasty – cousin Chen Jiao”

[11] Wang, 2015

[12] Wang, 2015

[13] Wang, 2015

[14] Wang, 2015; iNews, n.d., “Chen Ajiao is so proud of being pampered, she can’t buy a gift for her daughter to exchange it for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty.”

[15] Wang, 2015

[16] Wang, 2015

[17] Wang, 2015

[18] iNews, n.d., “The first queen Emperor Wuxi of the Han Dynasty – cousin Chen Jiao”

[19] iNews, n.d., “The first queen Emperor Wuxi of the Han Dynasty – cousin Chen Jiao”

[20] Wang, 2015

[21] iNews, n.d., “Chen Ajiao is so proud of being pampered, she can’t buy a gift for her daughter to exchange it for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty.”

[22] Wang, 2015

[23] Wang, 2015

[24] iNews, n.d., “Chen Ajiao is so proud of being pampered, she can’t buy a gift for her daughter to exchange it for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty.”

[25] iNews, n.d., “Chen Ajiao is so proud of being pampered, she can’t buy a gift for her daughter to exchange it for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty.”

[26] Wang, 2015

[27] Wang, 2015

[28] Wang, 2015

[29] Wang, 2015

[30] Wang, 2015, p. 115

[31] Wang, 2015

[32] Wang, 2015; iNews, n.d., “Chen Ajiao is so proud of being pampered, she can’t buy a gift for her daughter to exchange it for Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty.”

[33] Wang, 2015

[34] Wang, 2015

[35] Wang, 2015

[36] Wang, 2015

[37] Wang, 2015

[38] Wang, 2015, p. 115

[39] Wang, 2015

[40] Wang, 2015

The post Empress Chen Jiao – The deposed Empress who practiced witchcraft appeared first on History of Royal Women.

June 1, 2024

Book News Week 23

Book News week 23 – 3 June – 9 June 2024

Name Unknown: The Life of a Rusian Queen

Paperback – 3 June 2024 (US & UK)

The Lost Queen: The Surprising Life of Catherine of Braganza, Britain’s Forgotten Monarch

Hardcover – 6 June 2024 (UK)

Catherine de’ Medici: The Life and Times of the Serpent Queen

Hardcover – 6 June 2024 (UK)

Berengaria of Navarre: Queen of England, Lord of Le Mans (Lives of Royal Women)

Hardcover – 3 June 2024 (UK & US)

Hunting the Falcon: Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn and the Marriage That Shook Europe

Paperback – 6 June 2024 (UK)

The Royal Wardrobe: peek into the wardrobes of history’s most fashionable royals

Paperback – 6 June 2024 (UK & US)

The post Book News Week 23 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 31, 2024

Empress Wang Zhi – The previously married Empress Consort of the Han Dynasty

Empress Wang Zhi was the first Chinese Empress to have been previously married before becoming Empress Consort. She was the second Empress to Emperor Jing of Han. She was also the mother of Emperor Wu of Han. Empress Wang Zhi has a tarnished reputation for letting her relatives interfere in politics.[1] Still, Empress Wang Zhi’s story shows an intelligent woman who used her intellect to rise to the position of Empress Dowager.[2]

The birth date of Empress Wang Zhi is unknown. Her father was Wang Zhong. Her mother was Zang Er, who was the granddaughter of King Zang Tu of Yan.[3] Wang Zhi was the eldest of three siblings. She had a brother named Wang Xin and a sister named Wang Xu. After Wang Zhong died, Zang Er would remarry a man named Tian of Changling.[4] She then had two more sons named Tian Fen and Tian Sheng.

Wang Zhi married a man named Jin Wangsun. She bore him a daughter named Jin Su.[5] However, Wang Zhi’s humble life would soon change. One day, a fortune teller told Zang Er that her daughters would have honour and riches.[6] This fortune excited Zang Er, and she made grander plans for her daughters.[7] She ordered Jin Wangsun to divorce Wang Zhi and send her back home.[8] However, Jin Wangsun refused to divorce his wife.[9] Zang Er then managed to smuggle both of her daughters to the Crown Prince’s palace.[10]

Wang Zhi and Wang Xu managed to be favoured by Liu Qi, the Crown Prince. However, Wang Zhi was his particular favourite alongside Concubine Li, who bore him his eldest son.[11] She was given the title of Consort.[12] Consort Wang Zhi gave Prince Liu Qi three daughters. In the year of Prince Liu Qi’s enthronement as Emperor Jing, she told him that she had a dream that she would give birth to an Emperor.[13] This fascinated Prince Liu Qi, and he spent the night with her.[14] She conceived and bore him a son named Prince Liu Che (the future Emperor Wu of Han).[15]

After the birth of Prince Liu Che, Consort Wang Zhi’s status did not change.[16] Emperor Jing made Bo his Empress. However, Empress Bo was not favoured by him because she failed to produce children.[17] In 153 B.C.E., Emperor Jing appointed Concubine Li’s son, Liu Rong, the Crown Prince. In 151 B.C.E., Emperor Jing officially deposed Empress Bo. Even though the Empress position was vacant, he was hesitant to appoint another Empress.[18] He contemplated if his next Empress should be Concubine Li or Consort Wang Zhi.[19] He leaned towards the former.[20]

One day, Emperor Jing fell ill and was depressed. He asked Concubine Li that if she became the next Empress, if she could be willing to take care of all his sons after he died.[21] He also asked Concubine Li if she would be willing to marry her son to Chen Jiao, who was the Grand Princess Liu Piao’s daughter.[22] Concubine Li refused to take care of all his sons and was unwilling to let Prince Liu Rong marry Chen Jiao.[23] This angered Emperor Jing, and he decided to not make her the next Empress.[24] On the other hand, Consort Wang Zhi agreed to let her son marry Chen Jiao.[25] This earned her Grand Princess Liu Piao’s favour.[26] She praised her and Prince Liu Che in front of Emperor Jing, and he began to consider making him the Crown Prince instead.[27]

Since Emperor Jing was still angry with Concubine Li, Consort Wang Zhi found the opportunity to make herself the next Empress and her son the Crown Prince.[28] She urged the ministers to persuade the Emperor to make Concubine Li the Empress.[29] This infuriated Emperor Jing. He removed Liu Rong from the Crown Prince position and demoted him to Prince of Linjiang.[30] Then, he exiled him from the palace. Shortly after her son’s exile, Concubine Li died of “sadness and hatred.”[31]

On 6 June 150 B.C.E., Wang Zhi was officially invested as the Empress of China. Liu Che was made Crown Prince. Her three daughters were made the princesses of Yangxin, Nangong, and Longlu.[32] On 9 March 141 B.C.E., Emperor Jing died. Liu Che ascended to the throne as Emperor Wu of Han. Chen Jiao became his Empress. Wang Zhi was made Empress Dowager. Her mother was given the title of Lady of Pingyuan. Her father was given the posthumous title of Marquis of Gong. Tian Fen was made Marquis of Wu’an, and Tian Sheng was Marquis of Zhouyang. Empress Dowager Wang Zhi was reunited with Jin Su, who was her daughter from her previous marriage.[33] Jin Su was given the title of Lady of Xiucheng.

Empress Dowager Wang Zhi heavily influenced state affairs.[34] She let her half-brother, Tian Fen, become arrogant and lead a life of extravagance.[35] She even let him continue his grudge with Guan Fu (who was once his great-grandfather’s minister).[36] Guan Fu often spoke ill of him at several feasts that Tian Fen attended.[37] Tian Fen sent a memorial several times asking the Emperor to execute him and his family.[38] However, Guan Fu’s friend, Dou Ying, defended him.[39] The Emperor became frustrated with this issue and declared that he would kill his uncle, Dou Ying, and Guan Fu in order to settle the matter.[40] When Empress Dowager Wang Zhi learned that her son wanted to kill her half-brother, she became very upset.[41]

One day, Emperor Wu went to dine with Empress Dowager Wang Zhi. However, his mother refused to eat.[42] In a fit of rage, she told him, “You trample on my brother while I’m still alive. When I am dead, you will kill my relatives like fish!”[43] Emperor Wu had no choice but to let Tian Fen live.[44] He executed both Guan Fu and Dou Ying, along with their families.[45] This incident in history is recorded by ancient chroniclers as an “obvious example of calamities caused by imperial in-laws.”[46]

On 25 June 125 B.C.E., Empress Dowager Wang Zhi died. She was buried beside Emperor Jing in Yangling tomb.[47] Empress Dowager Wang Zhi has largely been criticised for letting her imperial family members get involved in state affairs.[48] Yet, Empress Wang Zhi was clever and resourceful.[49] She had great political acumen.[50] She used the opportunities to rise to power and crush her rival. It is no wonder why she came out the victor. Empress Wang Zhi still continues to fascinate and puzzle historians to this day.[51]

Sources:

Bao S. (2015). “Wang Zhi, Empress of Emperor Jing”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. pp. 215-217.

iMedia. (n.d.). “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”. Retrieved on 9 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/history/a048425ea....

[1] Bao, 2015

[2] Bao, 2015

[3] Bao, 2015

[4] Bao, 2015

[5] Bao, 2015

[6] Bao, 2015

[7] Bao, 2015

[8] Bao, 2015

[9] Bao, 2015

[10] Bao, 2015

[11] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[12] Bao, 2015

[13] Bao, 2015

[14] Bao, 2015

[15] Bao, 2015

[16] Bao, 2015

[17] Bao, 2015

[18] Bao, 2015

[19] Bao, 2015

[20] Bao, 2015

[21] Bao, 2015

[22] Bao, 2015

[23] Bao, 2015

[24] Bao, 2015

[25] Bao, 2015

[26] Bao, 2015

[27] Bao, 2015

[28] Bao, 2015

[29] Bao, 2015

[30] Bao, 2015; iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[31] Bao, 2015, p. 216

[32] Bao, 2015

[33] Bao, 2015

[34] Bao, 2015

[35] Bao, 2015

[36] Bao, 2015

[37] Bao, 2015

[38] Bao, 2015

[39] Bao, 2015

[40] Bao, 2015

[41] Bao, 2015

[42] Bao, 2015

[43] Bao, 2015, p. 217

[44] Bao, 2015

[45] Bao, 2015

[46] Bao, 2015, p. 217

[47] Bao, 2015

[48] Bao, 2015

[49] Bao, 2015

[50] Bao, 2015

[51] Bao, 2015

The post Empress Wang Zhi – The previously married Empress Consort of the Han Dynasty appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 30, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The loss of a son

Queen Isabella’s first child and namesake daughter had been born before she succeeded her half-brother as Queen. However, a second pregnancy was not quite so quick to happen.

Her first child was born on 2 October 1470, and for several years, she consulted doctors, prayed at sanctuaries and sought the intervention of saints. She also starved herself and engaged in self-mortification. She had begun to worry that her fertility issues were a sign of God’s disfavour.1

We know that she had at least one miscarriage or stillbirth during these years. It is unclear how long she was pregnant, and currently, the medical world sees it as a stillbirth if the fetal death occurred from 28 weeks gestation.2 It was certainly clear enough to determine that the child she lost in 1475 was a boy.3 And it seemed that Ferdinand only returned to Isabella in January 1475, so a miscarriage appears more likely.

These were the early days of her reign when the threat from her niece Joanna and the Portuguese was still high. Isabella hurried towards the city of Toledo on horseback as she was dependent on their support. After arranging the support of Toledo, she set out towards Valladolid and apparently rode so hard that she had to stop in Avila, where she lost the baby on 31 May 1475.

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)

The scene as portrayed in Isabel (2011) (Screenshot/Fair Use)She had to rest for a month as war with the Portuguese began in earnest. By July, she was eagerly getting ready for war. She would have to wait three more years for the birth of a son.

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The loss of a son appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 28, 2024

Palais Leuchtenberg – A city palace

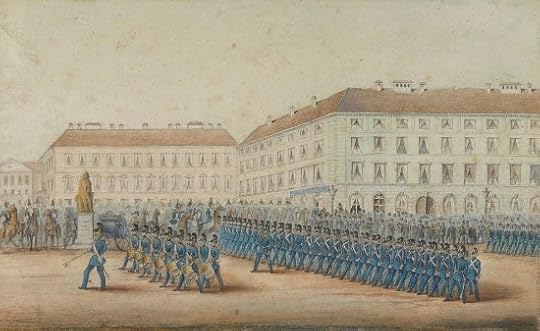

The Palais Leuchtenberg was built in the 19th century for Eugène de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg, and it was the largest palace in Munich. Between 1853 and 1933, it was known as the Luitpold Palais. It currently houses the Bavarian State Ministry of Finance.

Eugène de Beauharnais, husband of Princess Augusta of Bavaria, the sister of the future King Ludwig I of Bavaria, commissioned Leo von Klenze to build the palace between 1817 and 1820. It was based on the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. At the time, it was the first building on the Ludwigstraße.

Eugène and Augusta moved into the palace in 1821. She had found her suite too small upon their first inspection in September 1821, but luckily, there was still time for it to be enlarged. She thought “all the furnishings rich and elegant.”1 Eugène did not enjoy his new home for very long, and he died there in 1824. Augusta was a widow for 27 years. At her beloved Palais Leuchtenberg, Augusta died on 13 May 1851 of pneumonia following a stroke. Tragically, none of her four surviving children were with her. She was interred with her husband at the St. Michael’s Church in Munich.

The Palace in 1852 (public domain)

The Palace in 1852 (public domain)After Augusta’s death, the palace was sold to Prince Luitpold, who later became Prince Regent of Bavaria. Their son, the future King Ludwig III, made his home there with his wife, Archduchess Maria Theresa. Their son, Crown Prince Rupprecht, was born there in 1869.

Following the end of the monarchy in 1918, it remained in private property but some of the smaller outbuildings were converted. Rupprecht’s son, Albrecht, lived there until 1939. The palace was badly damaged during the Second World War. It was acquired by the Free State of Bavaria in 1957 and demolished.

A new building was built there between 1963 and 1967. The façade is a reconstruction of the original palace with a few differences. A few bits of the interior can now be found at Nymphenburg Palace.

The post Palais Leuchtenberg – A city palace appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 26, 2024

Euphrosyne of Kyiv – An influential Queen Mother

One of the dynasties the Rurikid dynasty intermarried the most with was the Arpads of Hungary. The marriage of Euphrosyne of Kyiv with King Geza II of Hungary seems to be one of the most successful of these unions.

Early Life

Euphrosyne was the only known daughter of Mstislav I, Grand Prince of Kyiv, by his second wife, Liubava Dmitrievna Zavidich. She was probably born around 1130, the same year her future husband was born. Euphrosyne had two full brothers, Vladimir and Yaropolk. By her father’s first marriage to Christina Ingesdotter of Sweden, she had many half-siblings, including Malmfred, Ingeborg, and Dobrodeia, who all married foreign princes before she was born. Euphrosyne’s father died in 1132, and she seems to have been raised by her mother.

Queen of Hungary

Most likely in 1146, Euphrosyne married Geza II, King of Hungary. They were both about sixteen at the time. The marriage was possibly arranged as an alliance against the Byzantine Empire. At this time, Hungary was expanding south into Croatia and Dalmatia, resulting in military conflicts with the Byzantine. Therefore, Hungary was looking for allies among its Slavic neighbours. Geza’s mother, Helena of Serbia, was also a daughter of a Slavic-Orthodox prince. At the beginning of her marriage, it is possible that Euphrosyne could have looked up to her mother-in-law. Helena was regent for Geza during his minority, and even during her husband’s lifetime, she was a powerful queen consort. Just like Euphrosyne, Helena was raised Orthodox and married a Catholic.

Another reason for this marriage could be the fact that Geza was in conflict with his cousin, Boris, at the time. Boris was the son of Euphrosyne’s aunt, Euphemia. Euphemia had been married to Coloman, who was king of Hungary from 1096 to 1116. When she was pregnant with Boris, Euphemia was accused of adultery and sent back to Kyiv. Due to this, Coloman did not consider Boris to be his son. Boris, however, considered himself Coloman’s son. When Stephen II of Hungary, Coloman’s son from his first marriage, died childless in 1131, he was succeeded by Geza’s father, Bela II. Boris tried to seize the throne from Bela with the help of the Byzantine Emperor but failed. In 1145, he tried again, this time trying to take the throne from Geza. Boris being allied to the Byzantine Emperor could be another reason why Geza was seeking an alliance against the Empire. Also, by marrying Euphrosyne, Geza could keep the alliance with Kyivan Rus in place.

In the summer of 1147, Euphrosyne gave birth to her first child, a son named Stephen. King Louis VII of France was passing through Hungary at the time on the way to the Second Crusade and stood in as Stephen’s godfather. Louis’s wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, was accompanying him on the journey. It is possible that Euphrosyne and Eleanor could have met, but no sources mention this.

Euphrosyne kept in touch with her siblings after her marriage. In 1148 or 1149, Euphrosyne’s older half-brother, Iziaslav II, lost the throne of Kyiv to their uncle, Yuri. Iziaslav looked for support from his western neighbours, including Geza. Geza’s armies ended up fighting a total of six times in Rus from 1148 to 1152. In 1150, a marriage was arranged between Euphrosyne’s full-brother, Vladimir, and a first cousin of Geza. Euphrosyne took part in arranging this marriage, and the Kyivan Chronicle mentions that at the wedding, she feasted with her brothers and gave them gifts. In 1155, Euphrosyne’s mother visited her in Hungary.

Euphrosyne had a close connection to the Hospitaller order. In 1157, after the death of Archbishop Martirius of Esztergom, she completed the construction of the Hospitaller convent at Székesfehérvár, which he started. She also donated many properties to the foundation.

Euphrosyne and Geza had eight children together:

Stephen III (1147-1172), King of Hungary from 1162 to 1172.

Bela III (c.1148-1196) King of Hungary from 1172 to 1196.

Elizabeth (c.1149-after 1189) Married Frederick, Duke of Bohemia.

Geza (c.1151-c.1210) Pretender to the Hungarian throne.

Odola, married Sviatopluk, Bohemian prince.

Arpad, died in childhood.

Helena (c.1158-1199) Married Leopold V, Duke of Austria

Margaret (1162-1208) Married firstly, Isaac Dukas and secondly, Andrew, Ban of Slavonia. Possibly married thirdly, Mercurius, Ban of Slavonia.

Geza died on 31 May 1162. During her widowhood, Euphrosyne would become a very powerful queen mother of Hungary, just like another Rus princess, Anastasia, did a century before.

Regency and Reign of Stephen III

Since Euphrosyne’s eldest son, Stephen, was barely fifteen when his father died, she stepped in to rule as regent. However, his accession was challenged by his two uncles, Ladislaus and Stephen. Ladislaus was the first to claim the crown and was crowned as King of Hungary in July 1162. Ladislaus was supported by the Byzantine Emperor, Manuel Komnenos. Soon afterwards, Stephen, possibly along with Euphrosyne and her other children, fled to Austria and then to Bratislava. Euphrosyne soon found support from the Bohemian King, Vladislaus II, and the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I. As a result of the alliance with Bohemia, Euphrosyne’s eldest daughters, Elizabeth and Odola, were married to Vladislaus’s two eldest sons, Frederick and Svatopluk, respectively.

Ladislaus’s reign did not last long, as he died in January 1163. His brother, Stephen, then had himself crowned as King of Hungary as Stephen IV. Euphrosyne and Stephen III raised an army, and Stephen IV was defeated in battle on 19 June 1163. After this, Stephen III was back on the throne. Euphrosyne continued to rule with him and was involved in church affairs.

That same year, Euphrosyne took part in a peace treaty with Byzantine Emperor Manuel Komnenos. On the advice of Euphrosyne and the Archbishop of Esztergom, her second son, Bela, was sent to Constantinople. Since Manuel had no sons at the time, Bela was betrothed to his daughter, Maria, and named as his heir. Bela was baptised in the Orthodox Church as Alexios and was given the title of despot.

The uneasy relationship with the Byzantine continued, and in 1164, Manuel and Bela attacked forces loyal to Stephen. There was much territory that was disputed between the two countries, such as the Dalmatian Coast. In 1164, Stephen was betrothed to a daughter of the Rus prince, Yaroslav Osmomysl of Halych. This betrothal was possibly arranged by Euphrosyne herself. However, the betrothal was annulled in 1166, possibly due to pressure from Emperor Manuel. Soon, Stephen was betrothed to Agnes of Austria, daughter of Henry II, Duke of Austria, who was a close ally of Stephen. The Hungarian-Byzantine War ended in 1167, with the Byzantine gaining control of the Dalmatian coast and Bosnia. In 1168, Stephen and Agnes were married.

In 1169, Euphrosyne appeared first in a list of lay advisors of the king promoting papal reforms in Hungary. Euphrosyne was also a staunch supporter of the military order, the Hospitallers. She participated in the founding of the first Hospitallers convent in Hungary. Under Euphrosyne, the convent building was finished, and she donated fifty-five of her properties to this foundation.

Reign of Bela III

Stephen died on 4 March 1172. According to a later chronicle, he was poisoned on the orders of his younger brother, Bela, but this is unconfirmed. Stephen left behind no surviving children, so Bela was next in line for the throne. The nobles of Hungary invited Bela to take the throne.

Bela was no longer needed as Emperor Manuel’s heir. In 1169, a son was born to Manuel, and the emperor married Bela off to his sister-in-law instead of his daughter. Bela arrived back in Hungary in late April or early May of that year, but due to a conflict with the Archbishop of Esztergom, he was not crowned until January 1173. Euphrosyne was not in favour of Bela’s accession and instead preferred her younger son, Geza. The reason for this could be that Bela had spent years at the Byzantine court and may have preferred a Byzantine approach to ruling his kingdom rather than a Hungarian one.

Since Euphrosyne preferred Geza, she eventually fell out with Bela. Soon after Bela’s coronation, he arrested Geza. Geza soon escaped, possibly with Euphrosyne’s help, but he was arrested again in 1177. Euphrosyne might have been imprisoned with Geza around this time. By 1186, Euphrosyne was reported to be imprisoned in Branicevo (today in Serbia).

Later Life

Bela would eventually exile Euphrosyne. This might have happened as late as 1186. Geza was released between 1186 and 1189. In her exile, Euphrosyne is believed to have travelled to Constantinople and then on to Jerusalem. At the Hospital of Saint John in Jerusalem, Euphrosyne became a Hospitaller nun.

It is not entirely clear what became of Euphrosyne after this. She is sometimes thought to have died this year, but she is also said to have lived until 1193. Either way, she probably did not remain in Jerusalem for long. In 1187, Jerusalem was captured by Saladin, and all crusading orders left the city. For a while, it seems that many thought that Euphrosyne died near Jerusalem, and was buried in the church of St. Theodosius in Jerusalem, and her remains were later transferred back to Hungary. However, it is now believed that her death and burial in Jerusalem have been confused with another Rus princess, St. Euphrosyne of Polotsk, who died in Jerusalem. According to a 1272 document, Euphrosyne was buried at the Hospitaller convent at Székesfehérvár, which she founded.

In conclusion, Euphrosyne’s life seems to have been quite an adventurous one. A Rus princess married in Hungary, she fiercely defended the rights of her older son when her husband died. After her first son died, she was involved in a conflict with her younger son and was exiled due to it. Euphrosyne is notable for having been the last Rus princess to rule as Queen of Hungary and the last Rus princess to rule over a Latin Christian kingdom.

Sources

Font, Marta; “The princess of Kievan Rus in Hungarian History” on hromada.hu

Mielke, Christopher; “Every hiacinth the garden wears: the material culture of medieval queens of Hungary (1000-1395)”

Mielke, Christopher; “No Country for Old Women: Burial Practices and Patterns of Hungarian Queens of the Arpad Dynasty (975-1301)”

Mielke, Christopher; The Archaeology and Material Culture of Queenship in Medieval Hungary, 1000-1395

Raffensperger, Christian; Ties of Kinship: Genealogy and Dynastic Marriage in Kyivan Rus’

Voloshchuk, Myroslav; “Ruthenian-Hungarian Matrimonial Connections in the Context of the Rurik Inter-dynasty Policy of the 10th-14th centuries: Selected Statistical Data”

Zajac, Natalia Anna Makaryk; “Women Between West and East: the Inter-Rite Marriages of the Kyivan Rus’ Dynasty, ca. 1000-1204”

“Euphrosyne Mstislavna” on the website The Court of Russian Princesses of the XI-XVI centuries

The post Euphrosyne of Kyiv – An influential Queen Mother appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 25, 2024

Book News Week 22

Book News Week 22 – 27 May- 2 June 2024

The Powerful Women of Outremer: Forgotten Heroines of the Crusader States

Hardcover – 30 May 2024 (US)

Cult, Culture, and Authority: Princess Lieu Hanh in Vietnamese History (Southeast Asia: Politics, Meaning, and Memory)

Paperback – 31 May 2024 (US & UK)

Plantagenet Princesses: The Daughters of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II

Paperback – 30 May 2024 (UK)

The post Book News Week 22 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 24, 2024

Empress Bo – The first deposed Empress in Chinese history

Empress Bo was the first Empress to be deposed in Chinese history. She was the first wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty. She was from a powerful family. Her great-aunt was Grand Empress Dowager Bo of China. Yet, she failed to give the Emperor a son. Because of her infertility, Empress Bo would suffer drastic consequences that left her miserable.

The birth date of Empress Bo is unknown. She was from the powerful Bo clan. Her first name also remains unrecorded.[1] Her parents’ names are also unknown.[2] What is known is that she was the grandniece of Grand Empress Dowager Bo.[3] She was brought up well.[4] She was known to be “virtuous and decent” [5] and “dignified and generous.” [6]

In 179 B.C.E., Bo married the Crown Prince, Liu Qi (the future Emperor Jing). The marriage was arranged by Grand Empress Dowager Bo, who hoped that the marriage would increase the status of the Bo family.[7] However, Princess Bo failed to produce any children with Liu Qi.[8] Princess Bo’s barrenness caused her husband to turn his affections on other women.[9] His notable favourites were Concubine Li (who was the mother of his eldest son named Liu Rong) and Consort Wang Zhi (who would later be Emperor Jing’s second Empress).[10] Consort Wang Zhi bore him three daughters and a son named Liu Che (the future Emperor Wu of Han). Therefore, the fact that Princess Bo failed to have any children while his other concubines did often left her humiliated.[11]

In 157 B.C.E., Liu Qi ascended the throne as Emperor Jing. He made Bo his Empress.[12] Yet, the Empress status only left her more insecure.[13] An Empress’s primary role was to bear a son.[14] Each of Emperor Jing’s six concubines had given him a total of fourteen children.[15] Yet, Empress Bo remained childless throughout their marriage.[16] This proved that Empress Bo was infertile and incapable of bearing any children.[17] On 9 June 155 B.C.E., Grand Empress Dowager Bo died. Empress Bo no longer had anyone powerful enough to help her with her situation.[18] It would not be long until she would be deemed unfit as an Empress and would be replaced.[19]

In 153 B.C.E., Emperor Jing made Liu Rong (his son whom he had with Concubine Li) the Crown Prince. It became evident that he would soon replace Bo as Empress in favour of one of his concubines.[20] In 151 B.C.E., Empress Bo was officially deposed because she did not have any children.[21] In 150 B.C.E., Emperor Jing removed Liu Rong from the Crown Prince position. He demoted him to Prince of Linjiang and exiled him from the palace. On 6 June 150 B.C.E., Emperor Jing made Consort Wang Zhi his Empress. He also made her son, Liu Che, the Crown Prince. This forced the deposed Empress Bo to move to another palace and live in misery.[22] The deposed Empress Bo spent the rest of her days alone and was often in despair.[23] In 147 B.C.E., the deposed Empress Bo died of melancholy.[24] She was buried south of Pingyang Pavilion, which was located in the eastern section of Chang’an.[25]

Empress Bo is truly a pitiful woman in Chinese history. Her story proves that even if a woman had a strong family background, she could still lose her position, status, respect, and favour if she failed to produce a son.[26] Empress Bo’s barrenness left her in a precarious position.[27] She was often humiliated, miserable, and replaceable.[28] If Empress Bo had been capable of giving Emperor Jing a son, her ending would have been very different.[29]

Sources:

Bao S. (2015). “Bo, Empress of Emperor Jing”. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge. p. 99.

iMedia. (n.d.). “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”. Retrieved on 7 October 2023 from https://min.news/en/history/a048425ea....

[1] Bao, 2015

[2] Bao, 2015

[3] Bao, 2015

[4] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[5] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”, para. 3

[6] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”, para. 3

[7] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[8] Bao, 2015

[9] Bao, 2015

[10] Bao, 2015

[11] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[12] Bao, 2015

[13] Bao, 2015

[14] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[15] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[16] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[17] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[18] Bao, 2015

[19] Bao, 2015

[20] Bao, 2015

[21] Bao, 2015

[22] iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[23] Bao, 2015; iMedia, n.d., “The first deposed queen in Chinese history, Empress Xiaojingbo, the original wife of Emperor Jing of the Han Dynasty”

[24] Bao, 2015

[25] Bao, 2015

[26] Bao, 2015

[27] Bao, 2015

[28] Bao, 2015

[29] Bao, 2015

The post Empress Bo – The first deposed Empress in Chinese history appeared first on History of Royal Women.

May 23, 2024

Queen Mary’s Chain-Link Bracelets

Queen Mary’s Chain-Link Bracelets are “two flexible bracelets, the rectangular pavé-set chain links with channel-set baguettes, one bracelet with three buckle-shaped panels, each mounted with a brilliant in rub-over setting, the other of very similar design, set with two brilliant collets and a central brooch element (originally detachable), mounted with a large brilliant; with snap fastenings to join together as a collar.”1

The bracelet with the three brilliants was purchased by Queen Mary in 1932, and the matching bracelet was made in 1935. They can link together to form a collar necklace, in which setting Queen Mary occassionally wore them.

The matching bracelet could have a brooch attached to it, which was made in 1934. It was set with a 9 3/4 carat brilliant from the Premier Mine in South Africa. This stone was given to Queen Mary for the opening of South Africa House.

Embed from Getty ImagesBoth the brooch and the two bracelets were bequeathed to Queen Elizabeth II, who only ever wore them as bracelets.

The post Queen Mary’s Chain-Link Bracelets appeared first on History of Royal Women.