Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 31

November 25, 2024

The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The death of Queen Isabella

From 14 September 1504, Queen Isabella I of Castile officially withdrew from government affairs, and she no longer signed state papers.

She had been greatly affected by the tragedies that had befallen her family in the past few years. The deaths of John and the stillbirth of his daughter, the death of her elder daughter Isabella and the subsequent death of Isabella’s son, Miguel, had been devastating.

Her health had been declining as well, and she was no longer able to travel longer distances. She spent Easter and June 1504 in a convent at Mejorada de Olmedo but spent most of the time at Medina del Campo. She spent much time in bed, and both she and Ferdinand fell ill with a fever in July. But while Ferdinand shook it off, Isabella had barely recovered when she was hit with another fever. The first signs of dropsy were also beginning to show.

At the end of September, Ferdinand secretly wrote to his daughter Joanna, Isabella’s heir, and her husband, Philip. He wrote, “Keep secret what I am about to tell you. No living person apart from the princess and the prince should know. I have not wanted to write about the illness and indisposition of the serene Queen, my very dear and much-loved wife, before because I thought that our Lord would give her health… but given what has happened and her current state, I am very fearful… our Lord might take her.”1

At the beginning of October, one Pedro Martir wrote, “The fever has not yet disappeared and seems to be in her very marrow. Day and night, she has an insatiable thirst and loathes food. The deadly tumour is between her skin and her flesh.”2

(public domain)

(public domain)On 12 October 1504, she signed her final document – her will. She named Joanna as her heir, but she and Ferdinand feared that her husband, Philip, would be the true ruler. She also named Ferdinand as an administrator in her kingdoms until Joanna was able to come.

As her health deteriorated, she said, “Do not weep for me, nor waste your time in fruitless recovery but pray rather for my soul.”3

On the morning of 26 November, Isabella received the sacraments from her confessor. She sighed and crossed herself. Just before noon, Isabella took her final breath. Ferdinand, who had been by her side, later wrote, “Her passing is for us the deepest grief that could ever happen to us in this life, for we have lost the best and most excellent wife that a king ever had.”4

Historian Jerónimo Zurita later wrote, “In all the realms, her death was mourned with such great pain and sentiment, not just by her subjects and countrymen, but commonly by all, that the least of the praise was that she had been the most excellent and valiant woman seen, not just in her time but for many centuries. This very Christian Queen took great account of sacred things and to increasing our Holy Catholic faith, and she did it with such study and care that it served to the advantage of everyone who reigns in all Christendom.”5

Not everyone was so full of praise. The Inquisition and the expulsion of the Jews had left scars. One denunciation made to the Royal Council in 1507 read, “The Queen is in hell, for she oppressed people…. Those kingdoms were very badly governed, and the King of Aragon and she did nothing but rob those kingdoms and were very tyrannical.”6

Her daughters learned the news of their mother’s death in various ways. Catherine in England likely only learned the news in December and her response has not been left to us. Maria in Portugal was heavily pregnant with her third child, and “almost in the final days of her expected labour”, and the devastating news was kept from her.7

Joanna learns of her mother’s death as portrayed in Isabel (2011)(Screenshot/Fair Use)

Joanna learns of her mother’s death as portrayed in Isabel (2011)(Screenshot/Fair Use)The new Queen of Castile was also pregnant, and her father advised her husband in December to keep the news from her to avoid it affecting the pregnancy.8 Letters confirming Isabella’s death reached Flanders on 12 December, but Philip refused to inform Joanna of her mother’s death. Nevertheless, within 12 days of the arrival of the letters with the bishop of Cordoba, Joanna received him and the news.9

The post The Year of Isabella I of Castile – The death of Queen Isabella appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 24, 2024

Eleanor of Austria – The eternal servant (Part three)

Rumours soon arose that Eleanor was having a love affair with her stepson, now King John III of Portugal. These rumours travelled as far as Poland and included that she was pregnant with John’s child. If there was any truth in the rumours, there was no way she would be allowed to marry John; she was too valuable of an asset to her brother. Her wedding agreement stated that she and any children she had were free to leave Portugal upon her husband’s death, but when Charles recalled her to Castile, King John refused to let Maria travel with her mother.

In May 1523, Eleanor left Portugal and Maria behind. They would not see each other again for almost 30 years, although there would be many attempts over the years to reunite mother and daughter. On her return home, Eleanor travelled via Tordesillas to visit her mother. In February 1525, it was Eleanor’s sister Catherine who became the next Queen of Portugal. For Maria, Catherine would be the only mother she knew.

Eleanor once again became a chess piece on her brother’s board. During the Battle of Pavia in 1525, King Francis I of France was taken prisoner by Charles’s troops. In an attempt to neutralise the French King, he was offered Eleanor as a bride, while her daughter Maria would marry Francis’s eldest son. From his prison, Francis tried to negotiate the terms Charles had set concerning land claims. When Francis’s sister Marguerite came to visit him, she met Eleanor, and the two reportedly became good friends. In the end, Francis promised to marry Eleanor, and he was released, although his two sons, Francis and Henry, were to take his place as prisoners. Charles and Francis came together to meet Eleanor on 17 February 1526, and he visited her again the following day. He left without her as she had to wait for the final settlement of the Treaty of Madrid before following Francis to France. In March, his two young sons arrived to take his place as prisoners, and Francis began to delay the signing of the treaty. This situation would last for three years.

The disappointed Eleanor tried to remain a loyal sister to Charles. In June 1527, Eleanor carried Charles’s first-born child to the baptismal font – he had finally married Isabella of Portugal in 1526. Eleanor travelled with the court as they tried to outpace the plague. Eleanor became frustrated with waiting and retired to a monastery for some time. Finally, in August 1529, through the negotiations of Margaret of Austria and Louise of Savoy, Francis’s mother, the so-called Ladies’ Peace settled matters. It renewed the Treaty of Madrid and, thus, Eleanor’s betrothal to King Francis.

In January 1530, the proxy wedding between Francis and Eleanor took place, and she began her travels north. She finally met her two stepsons, who joined her. She told them, “Come, my children, let us go to the fertile land of the king, your father.”1 On 1 July 1530, Eleanor finally entered her new homeland and “she was so desired by the whole kingdom and by all kinds of people that it was an incredible thing. […] As for the desire that everyone has for her coming, they say that she will be the cause of the restoration of this kingdom, which, in truth, from what I have heard, really needs it.”2 Eleanor may have been an angel of peace, but Francis was very much in love with another woman – Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly – who soon became Eleanor’s lady-in-waiting.

The wedding as portrayed in Carlos, Rey Emperador (2015)(Screenshot/Fair Use)

The wedding as portrayed in Carlos, Rey Emperador (2015)(Screenshot/Fair Use)On 7 July 1530, the in-person wedding took place. Ambassador Marsan wrote, “From what I know, the Queen, rejoicing to have such a King as her lord, does not simply wish to become his wife but his eternal servant.”3Éléonore d’Autriche: seconde épouse de François Ier by Michel Combet p.144'>4 Eleanor met Francis’s formidable mother not much later, but their relationship did not have much time to develop as Louise of Savoy died on 22 September 1531.

On 5 March 1531, Eleanor was crowned Queen of France at the Basilica of St Denis, and the festivities lasted for several days. For the next three years, Eleanor and the French went on a tour around France in order to present her as the new Queen. In 1533, she received a young Catherine de’ Medici, who was to marry Francis’s second son. The court finally returned to Paris at the end of February 1534. Eleanor’s life at court followed a regular pattern, but she managed to incorporate her love of music and hunting. She was also very pious. In 1538, she suffered from some kind of illness, and she wrote to Francis, “My illness gives me more trouble, and I cannot leave to go find you. […] Your letter has done me so much good that I have felt better since then and will leave as soon as possible, desiring nothing so much as to be in your company and good grace.”5

Although her political role in France was barely visible, she left a mark on the arts and culture. Several works of literature were dedicated to her. However, she remained in the shadows of Francis’s celebrated mistress, Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly and his sister, Queen Marguerite of Navarre.

Part four coming soon.

The post Eleanor of Austria – The eternal servant (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 23, 2024

Book News Week 48

Book News Week 48 – 25 November – 1 December 2024

Edward II’s Nieces: The Clare Sisters: Powerful Pawns of the Crown

Paperback – 30 November 2024 (US)

Stuart Spouses: A Compendium of Consorts from James I of Scotland to Queen Anne of Great Britain

Hardcover – 30 November 2024 (US)

Margaret, Duchess of Parma: The Emperor’s Daughter between Power and Image

Hardcover – 27 November 2024 (US)

The Most Maligned Women in History

Hardcover – 30 November 2024 (US)

Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War: Cousins of Anarchy

Paperback – 30 November 2024 (US)

Women in the Middle Ages: Illuminating the World of Peasants, Nuns, and Queens

Hardcover – 26 November 2024 (US)

Death and Life in the Ottoman Palace: Revelations of the Sultan Abdülhamid I Tomb (Edinburgh Studies on the Ottoman Empire)

Paperback – 30 November 2024 (US)

The Beaumonts: Kings of Jerusalem

Hardcover – 30 November 2024 (US)

The post Book News Week 48 appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 22, 2024

Queen Mother’s Coronation gown toile goes on display

The Queen Mother’s Coronation gown toile will go on display at Hillsborough Castle.

The new exhibition “Royal Style in the Making” will feature the Queen Mother’s Coronation gown toile, an 18th century-style ballgown worn by Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon and an evening dress worn by the late Queen Elizabeth II at a State Dinner during her official visit to Bahrain in 1979.

Click to view slideshow.In addition to the royal outfits on display, there will also be original design drawings from the finest British designers, such as Madame Handley Seymour, Norman Hartnell, Hardy Amies and Oliver Messel. The sketches from David Sassoon have some handwritten comments by Diana, Princess of Wales.

The exhibition at Hillsborough Castle will run from 15 March 2025 to 4 January 2026. Plan your visit here.

The post Queen Mother’s Coronation gown toile goes on display appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 21, 2024

250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part five)

Wilhelmina had never been the epitome of good health but from 1820, she began having more and more health troubles. The court physician often prescribed her rest and sea air. William even had a pavilion built for her at the beach in Scheveningen, which he gave to her for her birthday in 1827. That same year, she had also broken a rib after an unfortunate fall in the Palace in Laeken. Although she was not a politically active Queen, she was now the matriarch of the family and a much-loved one at that.

Some considered the Dutch court the most “boring court of Europe” due to Wilhelmina’s domesticity and William’s frugality.1 Every day at four o’clock, King Wiliam left his cabinet to take tea with Wilhelmina and her ladies.

On 21 May 1825, Wilhelmina’s second son, Prince Frederick, married his first cousin, Princess Louise of Prussia, who was 11 years younger. Princess Marianne was briefly engaged to Gustav, former Crown Prince of Sweden, before marrying Louise’s brother, Prince Albert, in 1830. Several grandchildren would follow over the years.

Despite her health troubles, Wilhelmina continued to travel between the southern and northern residences in The Hague and Brussels. When Belgium became a separate country in 1830, she no longer travelled to Brussels. She also continued to travel to Berlin almost every year. She would stay at the Niederländischen Palast, and after Princess Marianne married Prince Albert, she would stay with them as well.

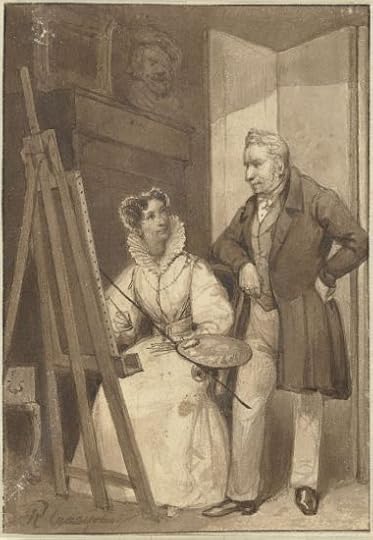

Wilhelmina with her husband (public domain)

Wilhelmina with her husband (public domain)Wilhelmina was a great lover of the arts and was known to have painted as well. She received lessons from Friedrich Bury, who was the court painter in Berlin. Unfortunately, very little of Wilhelmina’s art has survived. She was the patron of Bonaventura Genelli, who was able to study in Italy with an allowance from her.2

Wilhelmina’s last visit to Marianne was in the summer of 1836. During a visit to the Loo Palace in the summer of 1837, Wilhelmina’s health suddenly took a turn for the worse. She felt a little better by the end of September, much to the relief of her eldest son, who wrote, “I was very pleased with the good reports about Mama. I sincerely hope that her well-being continues and that the journey from the Loo to The Hague will not tire her too much. I will consider myself lucky if I see you both arrive at the winter residence in good health. I sent raspberries to Mama yesterday. I hope they arrived at the Loo in good order and that she likes them.”3

Wilhelmina was able to return to Noordeinde Palace, where she died on 12 October 1837 at the age of 62. For two weeks, Wilhelmina lay in state as her son watched over her. One observer wrote, “With sorrow, we heard the news of the Queen’s death. Her condition had deteriorated greatly in these last days, but death was still very unexpected for those around her and, it seems, for herself. What a striking contrast; all the grandeur of life in a palace or a narrow coffin. The Prince of Orange was fierce as ever; the King was very sad but calm. For 45 years, the Queen was with him in joys and sorrows, and, from what I hear from those who lived with them, happy. The King himself, on her return from the Loo, took the Queen out of the carriage, was completely occupied with her condition and was anxious to alleviate it, ate alone with her in the afternoon, and wanted no other dishes, no other wine than that which she might have to use. All members of the House were gathered at the Palace according to the wishes of the Sick; she died quietly. […] She may have had more for herself than we know. The interaction with her Court was very good; much cheerfulness, gentleness and love for her relations.”4

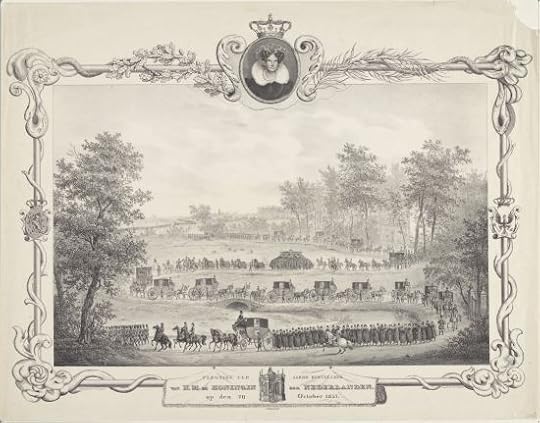

Wilhelmina’s funeral procession (public domain)

Wilhelmina’s funeral procession (public domain)On 26 October, Wilhelmina was buried in the New Church in Delft. Her coffin was draped in a mourning cloth and carried a crown on a cushion. Her husband, two sons and son-in-law, Albert, were in the procession. As was usual, the women of the family did not attend the funeral.

Wilhelmina had spent much of her life in the shadow of her mother-in-law. William ordered the destruction of her correspondence following her death, which leaves a large hole when trying to piece together her life.

Two years after Wilhelmina’s death, William proposed marriage to one of Wilhelmina’s former ladies-in-waiting, Henriette d’Oultremont. This caused such consternation that William decided to abdicate in favour of their son. The abdication took place on 7 October 1840, and William and Henriette married on 17 February 1841. Henriette was styled as Countess of Nassau.

William and Henriette decided to stay in Berlin, although he always intended to return to the Netherlands. His son had something else in mind. The marriage could not be valid in the Netherlands until it was registered, and William II wrote to his father that he could and would not receive Henriette due to the invalidity of the marriage. In addition, the public response to Henriette’s presence in the Netherlands could actually prove to be dangerous for her well-being. William was furious, and he angrily wrote to his son that he would come to The Hague personally and marry Henriette again. His son finally caved and allowed for the marriage to be registered.

Almost immediately, William and Henriette set off for the Netherlands, and they arrived at the Loo Palace on 10 October 1841. The citizens of Apeldoorn were surprisingly welcoming to their former King. William II was not at all happy with his father’s return to the Netherlands, and he refused to receive his father and Henriette in The Hague. William angrily departed for Berlin on 25 November.

The following years were hard for William. His health had begun to decline, but Henriette dedicated herself to taking care of him, to the praise of Prince Frederick. His declining health led William to try to reconcile with his son. On 12 July 1842, William and Henriette departed for The Hague after staying at the Loo Palace for a few weeks. It was a great visit, and William returned to Berlin in excellent spirits.

William collapsed on 12 December 1843 due to a stroke. He never awoke and died that same day at the age of 71.

The post 250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part five) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 20, 2024

250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part four)

Despite the affair, William also managed to father a child with his wife again. On 9 May 1810, Wilhelmina gave birth to a daughter named Marianne at the Niederländisches Palais in Berlin. She was named for her aunt, Princess Maria Anna of Hesse-Homburg. William wrote to his eldest son, “Our wishes have been granted, my dear Guillaume. Fortunately, Mom gave birth yesterday morning at four o’clock, and she gave you a little sister. Mom is doing as well as possible in such circumstances, and she is very happy. Especially since the little one is in good health and promises continuation of life.”1

Princess Wilhelmina with Princess Marianne (public domain)

Princess Wilhelmina with Princess Marianne (public domain)Things were looking up for the family, and Napoleon was now fighting a losing battle. Soon, there were calls for the family to return to the Netherlands and on 30 November 1813, William landed at Scheveningen. Their sons returned separately. As did Wilhelmina and Marianne, who returned to the Netherlands via Arnhem at the end of 1813. They returned to living at Noordeinde Palace. In early December, William wrote to his mother, “You have no idea, my dearest mother, of the reception I experienced and the joy that the nation shows at me being delivered from the French and my return to the homeland. The general cry is the assembly of the executive power and everyone expressed the desire that I be invested with sovereignty.”2 William was made Sovereign Prince of the Netherlands.

Attention now also turned to the marriage prospects of their eldest son, also named William. The most eligible Princess was Princess Charlotte of Wales, the only child of the future King George IV of the United Kingdom. Both the younger William and Charlotte herself were apprehensive about the match. He wrote to his father, “I am grateful that as a father you speak so openly about your future plans for me and for the space you offer to freely exchange ideas about them. […] The marriage with Princess Charlotte that you mention was also presented to me as a possibility by Constant. It doesn’t strike me as completely imaginary, although at the same time, it seems unlikely to me, and I confess to you that I hope it doesn’t happen.”3

When it became clear that William would one day be a head of state in his own right, a match with Charlotte, who was set to be Queen in her own right one day, seemed even more unlikely. Nevertheless, their engagement was announced on 30 March 1814, but Charlotte broke off the engagement in June. She wrote to her father, “He told me that our duties were divided, that our respective interests were in our different countries… Such an avowal was sufficient at once to prove to me Domestick (sic) happiness was out of the question.” 4 The younger William wrote home, “She behaved in such a revolting manner towards me that I can only congratulate myself on having learned her true character which could never have suited me, and it is therefore a true blessing from heaven that things took this turn.”5

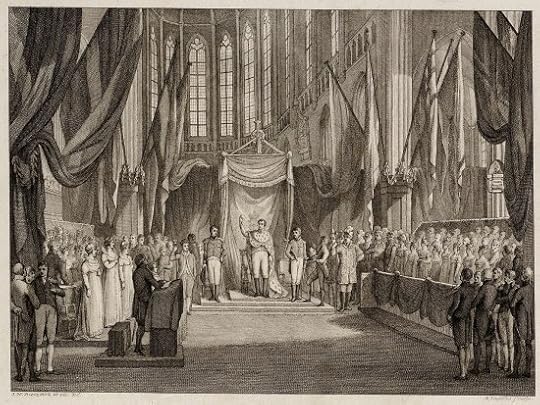

Inauguration of William as sovereign Prince of the Netherlands in Amsterdam on 30 March 1814 (public domain)

Inauguration of William as sovereign Prince of the Netherlands in Amsterdam on 30 March 1814 (public domain)On 30 March 1814, Wilhelmina’s husband was inaugurated as Sovereign Prince in Amsterdam with their two sons by his side. Just one year later, the Low Countries were united into a single kingdom, and William became the Netherlands’ first king, and Wilhelmina became its first queen. On 16 March 1815, William proclaimed himself King, and shortly after, he and Wilhelmina departed for Brussels. Their eldest son was wounded at the Battle of Waterloo, and Wilhelmina responded, “Like a Spartan woman,” and rushed to be by his side.6

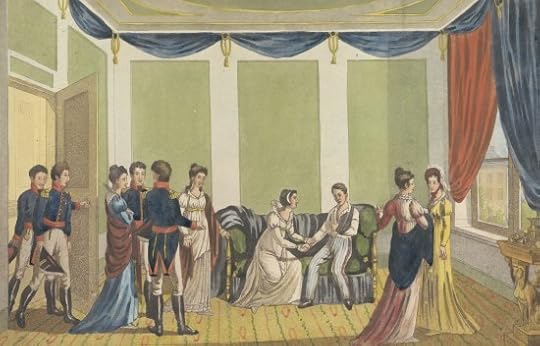

Wilhelmina visits her injured son (public domain)

Wilhelmina visits her injured son (public domain)On 21 September 1815, William received another inauguration, this time as King.

William’s inauguration as King (public domain)

William’s inauguration as King (public domain)The southern Netherlands were not quite as happy to be united with the northern parts, and William and Wilhelmina were not universally loved. “Apart from a few formal audiences and Männer-Dinners, both Highnesses see no one,” one observer wrote, “and the Queen does not yet know any ladies other than those who belong to the court.” 7 It was already known that Wilhelmina cared little for politics, but she became painfully shy when others tried to discuss it. By comparison, their eldest son was very popular in Brussels, which led to tensions.

After his failed engagement to Princess Charlotte of Wales, the younger William married Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna of Russia in 1816. Their wedding took place in Russia; thus, none of the family was present. They would not meet until the summer of 1816 when they travelled to Berlin to meet the newlyweds halfway. Anna had fallen pregnant quite quickly, and Wilhelmina’s first grandchild, yet another William, was born on 19 February 1817. Anna would later describe her mother-in-law as an “Angel.”8

Wilhelmina’s mother-in-law, also named Wilhelmina, and her sister-in-law, Louise, had spent a lot of time together after both were widowed. In the autumn of 1817, Louise travelled back to Germany for several weeks, and she wrote to her mother that she had forgotten how to write letters. It was her last journey abroad, and she returned home to spend the last two years of her life by her mother’s side. Louise died on 15 October 1819 after a short illness, and her mother would follow just eight months later. After her daughter’s death, Wilhelmina wrote, “Sometimes I think it was necessary for God to take her from me. Perhaps I was too attached to life and the wish not to be separated from my daughter. She could not get used to the thought that she would survive me as the natural order of things would be.”9

Part five coming soon.

The post 250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part four) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Marie Antoinette’s watch to go on display

A watch made for Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, is going on display at London’s Science Museum.

The watch features rubies, sapphires, platinum and gold. It has 823 parts and had no budget.

Click to view slideshow.Unfortunately, Marie Antoinette was guillotined before the watch was completed.

The watch will go on display as part of the Versailles: Science And Splendour exhibition. The exhibition will open on 12 December.

The watch was commissioned to Abraham-Louis Breguet in 1783, but it wasn’t completed until after his death in 1827. It is thought to be the most valuable watch in the world. It was stolen in 1983 and was missing for over 20 years. It was returned to the LA Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in 2008.

Sir Ian Blatchford, director and chief executive of the Science Museum Group, said: “This glorious watch will thrill visitors to Versailles: Science And Splendour, and is one of the most remarkable items we have ever secured. Even in the smallest details, the watch perfectly encapsulates meticulous engineering and a dedication to knowledge and beauty, ideals which are echoed throughout our exhibition and at Versailles itself.”

The exhibition will run until 21 April 2025. Plan your visit here.

The post Marie Antoinette’s watch to go on display appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 19, 2024

250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part three)

The family spent the summer and fall in Fulda and the winter and spring in Berlin. From 1804, the family lived in the Niederländische Palais at the Unter den Linden, which had been loaned to them. They also had the use of Schönhausen, a country residence. The children usually stayed behind in Berlin and only visited Fulda a handful of times. The children also sometimes stayed with their grandparents at Oranienstein. The Prince of Orange left England in 1801, and the Princess followed in 1802. In 1805, Pauline spent the entire winter making garters for her grandfather, which she presented to him for his birthday.

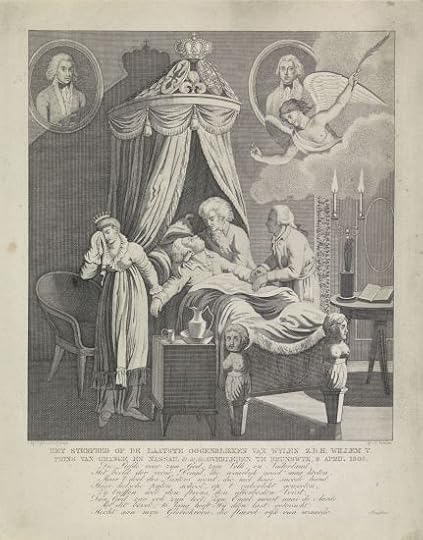

The death of William V, Prince of Orange (public domain)

The death of William V, Prince of Orange (public domain)In the early hours of 9 April 1806, William V, Prince of Orange, died in exile in Brunswick. At the request of his widow, he lay in state in the Bevernsches Palais. He was initially buried in Brunswick Cathedral, and Wilhelmina and her husband, now the new Prince and Princess of Orange, were in the procession. Wilhelmina was several months pregnant at the time.

Berlin was occupied by the French in 1806, and the family was forced to flee again. Wilhelmina was still weak from giving birth to a stillborn son in August. They travelled towards Königsberg but were forced to stop at Freienwalde when Pauline fell ill. William wrote, “Pauline has a mild indisposition, […] but I expect she will be fully recovered in a day or two.”1 On 15 December, Pauline was diagnosed with “nerve fevers” (probably typhoid fever). Her father still had hope and wrote, “She seems to be doing better.”1

Princess Pauline (public domain)

Princess Pauline (public domain)Six-year-old Pauline never did get better. She died in the early hours of 22 December. A heartbroken William wrote to his mother, “We had so hoped that Pauline’s illness would pass, our prayers would be heard, and she would be spared. Unfortunately for us, Providence has decided otherwise, and since 4.30 this morning, we have been plunged into deep mourning. Death has ripped our child, our hope and our love away from us. […] She leaves behind an empty void. Mimi and the boys are hanging in there, but this new test of Providence is heavy for us.”1

While William stayed with Pauline, Wilhelmina and the boys left for Berlin that very same day. She wrote the following day, “My love, the children and I, we arrived in Berlin at 1 o’clock this night, finally. I have taken plenty of precautions for myself and the boys. We shall overcome it. I have not seen General Clarke yet. God willing, you are well. I hope we shall be together again soon. Write to me about our poor little girl as soon as you have buried her. I am worried about you. […] The children talk about their father all the time; they say a thousand sweet things.”2

William arranged for her funeral in Freierwalde and wanted to follow the others to Berlin. Neither he nor Wilhelmina was initially granted access to the city. Eventually, Wilhelmina and the boys were let in. Napoleon was informed of young Pauline’s death and approved Wilhelmina’s stay in Berlin, but he was not so kind to William. William was arrested and deported over the Oder and was ordered to go to the Prussian King. Three weeks later, a devastated Wilhelmina wrote, “What a calamity, what a disaster that we have lost Pauline, our sweet, sweet little one. I can’t stop crying.”2 The loss of their baby, Pauline and William V, had hit them hard, but they also lost several lands because of Napoleon in 1806. It had become a very difficult year indeed.

William was eventually released and travelled hastily to be with Wilhelmina, even doing the final bit in a single stretch of 93 hours. About their reunion, he wrote, “My wife was still up, my dearest mother, and you can easily imagine the mutual satisfaction we experienced when we met again. She couldn’t wait to see me and received me in a way that completely surprised me.”3

While the health of their two sons was exemplary, William was most concerned about Wilhelmina. He wrote, “Mimi assures me that she is well now, & she no longer complains of faintness or weakness. Yet I see that the events have made a deep impression on her. She is much thinner and paler than normal, although she may not look as good because she wasn’t wearing any blush, which gave her a very different appearance”3

Meanwhile, William’s sister Louise had also been widowed, and their mother wanted nothing more than to be with Louise. However, Brunswick, too, would be swallowed up by Napoleon in 1807, and the two women ended up in Schleswig, where they shared a bedroom. After a year, they returned to Berlin, where they were reunited with the rest of the family. During the next few years, they would have severe financial difficulties.

Wilhelmina had never had much fervour for politics, and she wrote, “As for me, who is not concerned with the major issues of Europe, I spend my time bathing and toileting in the morning with Queen Luise, followed by lunch, also with her. Then, we watch the troops exercising in the garden. That means I don’t do anything in the afternoon, and I barely manage to think of anything for the evening.”4 She was a caring mother and had a tight grip on the education of their sons, William and Frederick.

Between 1807 and 1812, William fathered four children, with one Maria Dorothea Hoffmann. This was possibly a fake name for one of Wilhelmina’s ladies-in-waiting.5 It is unclear what Wilhelmina knew about these children as not all of her letters have survived. His mother certainly knew about the affair, and she wrote him a scathing letter. She blamed him for hurting his wife, the bad example he was setting for his sons and how he was risking a huge scandal. She added, “You are not in a bad marriage and could and should have found comfort at home.”6 He continued to see Maria Dorothea despite his mother’s pleas.

Part four coming soon.

The post 250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 18, 2024

250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part two)

On 18 June 1792, Wilhelmina’s mother-in-law wrote to her daughter, Louise, “I found Mimi [Wilhelmina] in our house, very healthy, very pretty and still with a little roundness.” She was by now starting to show.1 It was supposed to be a happy time, but the situation in France was concerning.

On 6 December 1792, Wilhelmina gave birth to a son – the future King William II. Her mother-in-law wrote proudly, “She gave us this morning a big, tall boy, very healthy and she herself is doing wonderfully, thanks to Heaven. We cannot give enough thanks to providence.[…] At 4 a.m. I was called, and at 8 a.m., the child was here. Mimi behaved like an angel, and although she was in great pain, she kept her word and tried to sing all the time between the pains.”2 The following morning, she added, “Mimi rested well last night. She is well today, and so is the newborn.”2

In a similar vein, William wrote to his sister, “Guillaume Frédéric Georges Louis is the name of my firstborn, whom I commend to Your favour, my dearest sister, assuring You that his coming has given me an inexpressible pleasure, although it was actually a most unpleasant moment, but as soon as it was over, the joy of too bigger. Mimi is doing well, as circumstances allow; I love that little mother & that little boy with all my heart. Now that he is well and truly here, I definitely ask you to be a godmother, so you don’t have to ask that question yourself because I am ahead of you. Adieu, dear sister, follow Mimi’s example & be assured of the perfect devotion with which I abide in life & in death.”3

In January 1793, King Louis XVI of France was executed, and just days later, the French revolutionaries declared war on William’s father, the Stadtholder. On 8 February, Wilhelmina’s mother-in-law wrote to her daughter, Louise, in lemon juice, “I do not want to hide from you that our situation is detestable and that in the event of an invasion, our defence measures could come too late if our allies cannot save us.”4 Wilhelmina’s husband had left for Frankfurt to join the allies in the war against France, which led to many worries for Wilhelmina. Her health suffered as a result, and she travelled to both the Loo Palace and Soestdijk Palace to recuperate. For the next two years, William was sometimes able to join her there in the winters.

The departure from Scheveningen (public domain)

The departure from Scheveningen (public domain)At the end of 1794, it became clear that the situation was spiralling and that the family would need to flee. Wilhelmina’s mother-in-law wrote to her daughter, “It is a cruel moment, my dear Loulou, that I write these lines to you. It is decided we are leaving. Mimi, the poor child and me.”5 Wilhelmina was a few weeks pregnant when they left from Scheveningen in the early hours of 18 January 1795. Wilhelmina’s husband, his father and his brother left from the same place around mightnight. The route to Germany had been blocked, so England was the only option. They landed at Yarmouth and were soon reunited. Wilhelmina’s father-in-law wrote, “If I will ever see my homeland again, I don’t know, but I will never stop loving it; whatever happens, I will always pray to God for its prosperity. That’s all I can do for her.”6

The family went to live in Kew Palace, also known as the Dutch House, granted to them by King George III and Queen Charlotte. This had also been the residence of the Prince of Orange’s mother, – Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of King George II. They were later also offered Hampton Court Palace and moved there in February. They tried to make a life for themselves in exile and regularly attended court cercles. In August 1795, Wilhelmina gave birth to a stillborn son. According to her husband, “she kept herself strong, ” but it must have been difficult.7 He had been itching to leave England, and he did so one month after the loss of their son. He left Wilhelmina behind and headed first to his sister Louise in Brunswick and then to Berlin. Wilhelmina would follow him in April 1796 with their little son. She, too, went via Brunswick to see her sister-in-law, Louise.

Louise wrote to her mother, “So I kissed this good Mimi and her little darling. The mother has a very good face, and her healthy appearance surprised me so much that I couldn’t believe it.”8 William was delighted to be reunited with his wife. However, he wrote to his mother that he was sorry that she was now separated from his little son. Now that they were reunited, Wilhelmina became pregnant again, and this time, all went well.

On 28 February 1797, she gave birth to a son named Frederick. Her mother-in-law was still in London, but she happily wrote to her son, “We have great thanks to give to Heaven for the happy delivery of our dear Mimi and for having given you a second son who appears so strong and robust. I do not need to tell you all the joy that this event has given me.”9

A third child – a daughter named Pauline – was born on 1 March 1800. Her father was not present at her birth and did not return to Berlin until the middle of April, just in time for her baptism. She received the names Wilhelmina Frederika Louise Pauline Charlotte. The name Pauline was for Emperor Paul I of Russia, which led to some trouble in the family. Louise wrote to her mother, “So, your latest grandchild is now a Christian and Mimi (Wilhelmina of Prussia) calls her Pauline because she thinks it is the most beautiful of the names. Last year, I would have admired her choice as a gesture to Paul, but since the Emperor has abandoned us so abruptly, it now seems to me to be reprehensible and ill-considered flattery.”10 As a response to the dissatisfaction over her name, she was nicknamed “Polly.”

Part three coming soon.

The post 250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 17, 2024

250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part one)

The year 2024 marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Wilhelmina of Prussia, the first Queen of the Netherlands.

Wilhelmina of Prussia was born on 18 November 1774 as the daughter of the future King Frederick William II of Prussia and his second wife, Frederica Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt. She was born during the reign of her great-uncle, King Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia. From her father’s first marriage to Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, she had an elder half-sister, Princess Frederica Charlotte, who married Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, in 1791. From the marriage to her mother, she had six siblings, of which one sister died young.

Wilhelmina was born in Potsdam and spent her youth in Berlin. We know she learned several languages and she was quite musical. Her mother took care of her religious education, but she was blamed for neglecting her children. One observer wrote. “Frederic [sic] William III. received the very worst of educations; so beyond all measure bad as only that of a crown Prince can be. His father troubled himself more about his illegitimate than his legitimate children. They were left to their mother. She, constantly embroiled with her finances, often did not see them for days together; they were therefore left to the care of their attendants and of their misanthropic Hofmeister Benisch.”1

Her great-uncle was a significant influence on their family. Frederick lacked empathy for her father and grandmother, who also happened to be the sister of his own unhappy wife. He wrote to his sister Amelia, “I have here now the good old Princess of Prussia [Wilhelmina’s grandmother]. She’s quite a burden, and I wish she was already on her way back to Berlin. She and her son spread a cloud of boredom and distaste!”2

When it came to the education of Wilhelmina’s brother (the future King Frederick William III), he agreed with finding a governor, “provided one could find the right person – not easy – and did not hurry over the choice.”2 Frederick was trying to raise an heir he could trust, but Wilhelmina was a girl and thus not important in the line of succession.

Wilhelmina met her future husband, the future King William I of the Netherlands, in 1787. He was her first cousin, as his mother, confusingly also named Wilhemina of Prussia, was the sister of her father. At the time, he was the Hereditary Prince of Orange, and the Kingdom of the Netherlands did not exist yet. His father, William V, Prince of Orange, was the Stadtholder of the United Provinces. He wrote to his father, “I believe her nature is like that of my sister, & You must admit, dear Father, that the comparison holds.”3 He wanted nothing more than to marry her.

The marriage was settled in the summer of 1789 when the elder Wilhelmina came to visit her brother’s court – he had acceded the throne in 1786. For a little while, William continued his military studies while the younger Wilhelmina (Mimi to her family) tried to learn Dutch.

It was initially supposed to be a double alliance – William was to marry Wilhelmina, while William’s sister Louise was to marry Wilhelmina’s brother, the future King Frederick William III. This second match failed, and Louise married Karl Georg August, Hereditary Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, in 1790, while Frederick William married Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz in 1793. As they waited for the final permission to marry, William wrote to his father, “I am deeply sorry, my dearest Father, that You cannot be here to judge Your future daughter-in-law. I’m sure she will please you immensely. Her appearance and her entertaining conversation are infinitely pleasant. People also say endless good things about her character. You can be convinced, dear Father, that I am committed to earning by my conduct the benefit that You are now doing me, and I beg Your fatherly blessing upon me and – if You allow me to call it that now – my future wife.”4

He also wrote to his sister, commending how well Wilhelmina was doing with learning Dutch. He wrote, “I am convinced, dear sister, that you would be surprised if you heard my niece read and speak Dutch because she has almost no accent and pronounces the letter g very well.”5

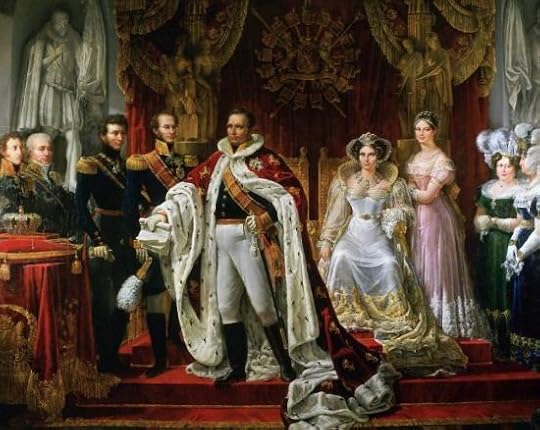

The wedding of William and Wilhelmina (public domain)

The wedding of William and Wilhelmina (public domain)The wedding finally took place on 1 October 1792. It turned out to be a busy season for weddings as Wilhelmina’s elder half-sister, Princess Frederica Charlotte, married Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, on 29 September. William considered it his dress rehearsal as it was exactly the same ceremony he and Wilhelmina were having.

On the day of his wedding, William wrote to his father, “My dearest Father, when the courier who carries this letter leaves Berlin, I shall be married, so I have the honour of informing you that I am at the height of my desires, finding myself united by indissoluble ties to everything that is most lovable, sweet and best. May I have the honour of assuring you, my dearest Father, that I am very happy. The day before yesterday, we had a dress rehearsal in the persons of the Duk of Yorck [sic] and Princess Frederique, whose marriage has just taken place and was blessed the same way as ours.6

For two weeks, Berlin celebrated the weddings with gun salutes, dinners, parties and operas. On 18 October, William and Wilhelmina left Berlin and arrived in The Hague eleven days later, where more festivities were planned. The newlyweds moved into Noordeinde Palace, then still known as the “Oude Hof.” However, William was often absent due to his military obligations in Breda, and so Wilhelmina spent a lot of time with her namesake mother-in-law. This led to doubts with her mother-in-law as she thought Wilhelmina could be too weak and tender for her son. Things turned around in the summer of 1792 when Wilhelmina fell pregnant with her first child.

Part two coming soon.

The post 250: Wilhelmina of Prussia, Queen of the Netherlands (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.