Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 190

February 7, 2020

Fotheringhay Castle and the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots

Some stone with a fence around it is now all that remains of Fotheringhay Castle. Three signs tell part of its story; one states the name of the former castle, a second that King Richard III was born there in 1452 and the third reminds the visitor that Mary, Queen of Scots was executed there on 8 February 1587.

Mary had fled to England in hopes of receiving England’s help with regaining her crown. However, Queen Elizabeth perceived her as a threat as Mary had once claimed England’s throne as her own (through her descent from Margaret Tudor, the sister of King Henry VIII). She became Elizabeth’s prisoner for many years, and she was kept in many different castles and manors over the years.

On 5 September 1586, a special tribunal was set up to hear the evidence against Mary, in yet another plot against Elizabeth. Mary herself was not informed of where she was going, and she arrived at Fotheringhay Castle on 25 September. She was accompanied by five or six servants. Mary refused to confess her guilt, and on 12 October a letter arrived from Elizabeth.

“You have in various ways, and manners attempted to take my life and to bring my kingdom to destruction by bloodshed. I have never proceeded so harshly against you but have, on the contrary, protected and maintained you like myself. These treasons will be proved to you, and all made manifest. Yet it is my will, that you answer the nobles and peers of the kingdom as if I were myself present. I therefore require, charge, and command that you make answer for I have been well informed of your arrogance. Act plainly and without reserve, and you will sooner be able to obtain favour of me. Elizabeth R.”

The following trial took place in a room above the Great Hall but her statement was not of her guilt. She said, “I am an absolute Queen, and will do nothing which will prejudice either mine own royal majesty, or other princes of my place and rank or my son. My mind is not yet dejected nor will I sink under my calamity… The laws and statutes of England are to me most unknown; I am destitute of counsellors, and who shall be my peers, I am utterly ignored. My papers and notes are taken from me, and no man dareth step forth as my advocate. I am clear of all crimes against the Queen. I have excited no man against her, and I am not to be charged but by mine own word or writing, which cannot be produced against me. Yet can I not deny but I have commended myself and my cause to foreign princes.”

On 19 November, the news arrived that parliament had passed the sentence of death on her. Mary was stripped of her honours and cloth of state. She was now “but a dead woman, without the honours and dignity of a Queen.” Mary replaced her cloth of state with pictures of the Passion of the Christ, and the building of a scaffold was begun in the Great Hall. Mary wrote to Elizabeth asking to be buried with the “other Queens of France” or near her mother. Yet Elizabeth waited to confirm the order of execution. She finally signed the order in early February.

Mary was told on 7 February that she was to die the following morning. She began to settle her affairs and wrote to her brother-in-law, King Henry III of France. At six in the morning, Mary dressed for her final performance. She wore a skirt and bodice of black satin over a russet brown petticoat and an overmantle of black satin embroidered with gold and trimmed with fur. She wore a white crepe headdress and a long lace veil. A gold rosary hung from her waist. She spent some time at prayer.

She walked down to the Great Hall, where the scaffold was now complete. Over 300 people had come to watch her die. She climbed the scaffold and took the pins out of her hair herself. Her outer clothes were removed, and she received fresh sleeves in russet, and so she was now dressed in red – signifying a Catholic martyr. She bade farewell to her weeping servants and forgave the executioner. A silk handkerchief was then tied over her eyes, and she laid her head down on the block. She spoke the words, “In manus tuas, domine, commendo spiritum meum” (Into your hands I commend my spirit) several times before the axe fell. It took two strikes to decapitate her except for a small part of sinew, which the executioner sawed through. He then lifted her head and declared, “God save the Queen.” Her head then fell from his grasp, leaving him holding her auburn wig.

Mary’s body was removed to another room while the scaffold, block and her clothes were burned. Her head was put on a velvet cushion and put on display in one of the windows so that the crowds outside could see it. Her body was hastily embalmed the following morning before being placed in a double coffin of oak and lead.

Click to view slideshow.

It wasn’t until 30 July 1587 that Mary’s body was moved to Peterborough. She was buried in a grave opposite of that of Catherine of Aragon. She was moved to Westminster Abbey on 28 October 1612. Fotheringhay Castle was abandoned after Mary’s execution, and it was mostly gone by the end of the 18th century.

The site is open for visitors.1

The post Fotheringhay Castle and the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 6, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The wedding of Wilhelmina and Henry

On 7 February 1901, the young Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands married Duke Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. He was one of three candidates who had been considered for the young Queen.

(public domain)

(public domain)Any British candidates had been vetoed because of the Boer War, and even Emperor Wilhelm II butted in and declared that only a German Prince would do. In May 1900, Wilhelmina and her mother Emma travelled to Schloss Schwarzburg in Thuringia to meet the three possibilities. They were: Frederick Henry (Friedrich Heinrich) of Prussia, who was a grandson of Princess Marianne of the Netherlands, and the two youngest sons of Frederick Francis II, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Adolf and Henry (Heinrich), but Adolf did not show up. Wilhelmina had met Henry previously in 1892 when she was just 12 years old, and they were second cousins as they were both descended from Paul I of Russia and Maria Feodorovna.

They met several times over the next few months after Wilhelmina had quickly vetoed Frederick Henry. In her memoirs, she wrote of their engagement in October, “On the 12th of October he came to luncheon. After the meal was over, the others withdrew and left us alone. Ten minutes later, we returned and announced our engagement. The die was cast. What a relief that always is on these occasions!”1 On 29 October, Wilhelmina excitedly wrote to her former governess Miss Winter, “I must begin by begging your pardon for not having written to you before now. But Darling, when one is engaged – letter writing becomes difficult; now the Duke has left and now I must thank you a thousand times for your loving telegram… letters and for all the wishes they contain. Oh, Darling, you cannot even faintly imagine how frantically happy I am and how much joy and sunshine has come upon my path.”2

The months leading up to the wedding were wrought with financial arrangements and discussions about the name of the House.

Nevertheless, Wilhelmina was thrilled, and she wrote to Miss Winter, “Oh, you don’t know how I am longing for my wedding to come to no more be separated from him and be able to live for him, what a happiness!”3

The Great Church in The Hague was chosen as the wedding venue, but celebrations had to be shortened following the deaths of Wilhelmina’s uncle the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach on 5 January and Queen Victoria on 22 January. On 31 January, Henry arrived in the Netherlands for the wedding. Several events took place in the following days, like a theatre performance and a soiree with tableaux vivants.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

The day of the wedding was a sunny but cold day. Crowds had gathered in the streets to catch a glimpse of the bride and groom. The civil wedding was performed at Noordeinde Palace before they were taken to the Great Church in the Golden Carriage. Wilhelmina did not agree to obey her husband. Following the ceremony, there was a breakfast at the Palace. Emma toasted the couple with the words, “In full confidence, I gave my child to the man of her choice.”4 Emma would move into a palace of her own after the wedding – Lange Voorhout Palace. Wilhelmina later wrote, “It was a magnificent wedding. Many members of both families were present, and the whole country rejoiced in our happiness. We received splendid presents, including the golden coach, offered to me by Amsterdam in 1898, which was finished just in time.”5

They spent their honeymoon at the snow-covered Loo Palace.

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The wedding of Wilhelmina and Henry appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 5, 2020

The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women: Queen Victoria and the Women’s Movement by Arianne Chernock Book Review

Queen Victoria, who reigned from 1837 until 1901, would have been the perfect forerunner for the women’s movement but unfortunately, the nineteenth-century feminists were to be disappointed. Queen Victoria condemned the women’s rights movement with the words, “the movement of the present day to place women in same position as to profession – as men” was “mad & utterly demoralising” and “the Queen feels so strongly upon this dangerous & unchristian & unnatural cry & movement of ‘woman’s rights’… that she is most anxious that Mr Gladstone & other shld take some steps to check this alarming danger & to make whatever use they can of her name… Let woman be what God intended; a helpmate for a man – but with totally different duties & vocations.”

Her words would not be available for the public until many decades later. The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women: Queen Victoria and the Women’s Movement by Arianne Chernock is a wonderfully well-written look into a side of Queen Victoria that is surprising and perhaps disappointing to modern eyes. Unfortunately, the hardcover is rather expensive, so I hope if there is a paperback release, it will be a bit more affordable.

The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women: Queen Victoria and the Women’s Movement by Arianne Chernock is available now in both the UK and the US.

The post The Right to Rule and the Rights of Women: Queen Victoria and the Women’s Movement by Arianne Chernock Book Review appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 4, 2020

Marie-Thérèse Nguyễn Hữu Thị Lan – The last Empress of Vietnam

Marie-Thérèse Nguyễn Hữu Thị Lan was born on 14 December 1914 as the daughter of Pierre Nguyễn Hữu-Hào and Marie Lê Thị Binh. She was born in Gò Công which was then in the French colony of Cochinchina, and so Marie-Thérèse was a naturalised French citizen. She was known by her friends and family as Mariette. From the age of 12, she studied at the Couvent des Oiseaux in Neuilly-sur-Seine.

On 9 March 1934, her engagement to her distant cousin Bảo Đại, Emperor of Vietnam was announced. The New York Times reported, “Emperor Bao Dai, youthful Europeanised monarch of Annam, has chosen a commoner for a bride. His engagement to Miss Yuen Hu Hao, daughter of a wealthy Cochin-Chinese family, was announced today. The wedding will be on March 20.”1 The following day, Bảo Đại said of his future wife, “The future Queen, reared like us in France, combines in her person the graces of the West and the charms of the East. We who have had occasion to meet her believe that she is worthy to be our companion and our equal. We are certain by her conduct and example that she fully merits the title of First Woman of the Empire.”2

Of the four-day wedding ceremony, the New York Times wrote, “Pretty 18-year-old N’Guyen Huu Hao, a commoner from the neighbouring Cochin-China, became the bride of the youthful Emperor Bao Dai of Annam today. The Buddhist ritual was part of the four-day wedding ceremony. Only a small part was witnessed by the public, the rest taking place behind closely guarded doors in strictest family and official secrecy. N’Guyen Huu Hao, reared a Catholic, was educated in a French convent, and many subjects of the 21-year-old ruler grumbled because Bao Dai took a wife from outside their own faith.

As the marriage program began behind the walls of the royal palace, the exact religious status of N’Guyen Huu Hao – called Mariette in France – could not be ascertained. Last week it was announced that she intended to renounce Catholicism and embrace Buddhism upon becoming Queen of Annam, which is a part of French Indo-China. Yesterday, when she arrived here, reports from the Vatican said the necessary dispensations had apparently been granted to permit her to marry as a Catholic.

Palace censorship, however, cloaked the religious angle and most other details of the ceremony. N’Guyen Huu Hao, who will receive her final investiture as Queen on Saturday, is a slim striking girl, a member of a wealthy Cochin-China family, which has furnished martyrs to the cause of Catholicism for many generations.

In accordance with Oriental tradition, she was kept from the gaze of the Emperor until the start of the ceremony today. The highest mandarin commanding the citadel led the procession on horseback and dressed in full military uniform. The procession moved slowly from the guests’ palace to the royal palace while artillery salutes boomed. The bride was escorted by Princesses of the royal family and wives of the chief mandarins, all of them wearing rich, brocaded ceremonial robes and blue turbans.” 3

After the wedding, she was given the title of Imperial Princess and the name Nam Phương, which can be translated as “Fragrance of the South.” They went on to have five children together: Crown Prince Bảo Long (born 4 January 1936), Princess Phương Mai (born 1 August 1937), Princess Phương Liên (born 3 November 1938), Princess Phương Dung (born 5 February 1942) and Prince Bảo Thắng (born 30 September 1944). Her husband also had six other wives and concubines, but Marie-Thérèse remained his principal wife.

Embed from Getty Images

In 1945, her husband proclaimed the country’s independence from France and assumed the title of Emperor. He raised her to the rank of Empress with the style of Imperial Majesty. However, following the Second World War and the Japanese surrender, the revolutionary leader Hồ Chí Minh persuaded her husband to abdicate and to hand over power to the Việt Minh. Her husband was appointed “supreme advisor” to Hồ Chí Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam, but he was ousted the following year. He was able to return as “Chief of State of Vietnam” in 1949, only to be ousted again in 1955.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Marie-Thérèse and her children moved to France in 1947, and her children were educated at the same school that she had attended. She separated from her husband in 1955. The last Empress of Vietnam died on 16 September 1963 from a heart attack at her home in Chabrignac, France. She was still only 48 years old. She was buried in the local cemetery. Her husband survived her for 34 years – dying on 30 July 1997. Her eldest son became Head of the Imperial Family in exile, but he died childless in 2007. Her younger son took over the position upon his brother’s death, but he too died childless in 2017. The son of Emperor Bảo Đại and the concubine Lê Thị Phi Ánh, Bảo Ân, is the current head of the family.

The post Marie-Thérèse Nguyễn Hữu Thị Lan – The last Empress of Vietnam appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 3, 2020

Lost Kingdoms: Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt was established in 1922 under the Muhammad Ali dynasty following the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence by the United Kingdom. The previous Sultan of Egypt became King Fuad I of Egypt.

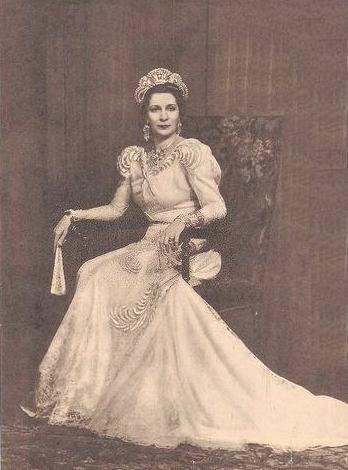

Queen Nazli (public domain)

Queen Nazli (public domain)King Fuad was married twice. His first wife was Shivakiar Ibrahim; also his first cousin once removed. Their son Ismail died in infancy, but a daughter named Fawkia survived to adulthood. They divorced in 1898 before Fuad became King of Egypt. During a dispute with her brother, Fuad was shot in the neck, but he survived. In 1919, he remarried to Nazli Sabri who was thus the first Queen of the modern Kingdom of Egypt. They went on to have a son and four daughters, including Fawzia, Queen of Iran.

Upon King Fuad’s death in 1936, he was succeeded by his only surviving son, who became King Farouk I. Farouk was also married twice. His first wife was Safinaz Zulficar, who became known as Queen Farida upon marriage. They were married on 20 January 1938, and they went on to have three daughters together. They were divorced on 19 November 1948, and while Farouk kept custody of their two eldest daughters, Farida took custody of their youngest daughter.

Farouk remarried to Narriman Sadek in 1951, and she gave birth to his only son, Ahmed Fuad, the following year. As it would turn out, she would be the last Queen of Egypt. Farouk was forced to abdicate in 1952 in favour of his infant son who became King Fuad II. The infant King reigned less than a year, and he too was exiled in 1953. Narriman and Farouk divorced in 1954.

Following the overthrow of the monarchy, the Republic of Egypt was declared. The infant King Fuad II is still alive, and he has two sons and a daughter with the French-born Dominique-France Loeb-Picard, also known as Fadila.

The post Lost Kingdoms: Kingdom of Egypt appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 2, 2020

Claudia Octavia – The neglected Empress

Claudia Octavia, or just Octavia, was born in late 39 AD or early 40 AD as the only daughter of the Emperor Claudius of the Roman Empire by his third wife, Valeria Messalina. Her father became Emperor in 41 AD, and she had a younger brother named Britannicus born around that time. Her mother was killed in 48 AD, and her father remarried his fourth and final wife Agrippina the Younger. She had a son named Nero (born 37 AD) from an earlier marriage to Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus.

To the astonishment of many, Octavia’s father soon began to show a preference for Nero as his successor, instead of his own son Britannicus. Nero was officially adopted by Claudius in 50 AD and was given the title “Princeps Iuventutis” – Prince of Youth – in 51 AD. In 53 AD, Octavia was married to her adopted brother Nero after she was legally transferred to another clan to avoid incest claims. Apparently her stepmother Agrippina had planned this marriage even before her own marriage to Claudius, and in order to achieve it, she had (ironically) brought up a claim of incest to the man who was betrothed to Octavia – Lucius Junius Silanis, a great-great-grandson of Augustus. The following year, Claudius died at the age of 63 – just before Britannicus reached the age of legal manhood, which was 14. It was soon claimed that Agrippina had had a hand in his death. His will was never read because it most likely named Britannicus as joint-heir or because it did not name Nero as his sole heir.

Nevertheless, Nero succeeded his adoptive father as Emperor, making Octavia Empress. It appears their marriage was loveless and also childless. However, the leading political force was his mother, Agrippina. Coins were minted with their busts facing each other, and her titles were on the more important side of the coins, the “heads” side. However, Nero soon came to resent his mother, and at the age of 18, he declared his independence from his mother.

In 55 AD, Nero fell in love with a former slave by the name of Claudia Acte and began an affair with her to the horror of his mother. Octavia’s response is not recorded. In response to Agrippina’s lessening power of him, she threatened to transfer her support to Britannicus as a better candidate for the throne. Nero apparently had him poisoned at a family dinner. Agrippina then teamed up with Octavia to consolidate her own influence. Nero stripped his mother of her personal bodyguard and forced her to move out of the palace. She had now definitely fallen from grace.

Nero remained married to Octavia, but Acte had been replaced by the ambitious Poppaea Sabina, whose mother had been killed by Octavia’s mother. Poppaea Sabina believed that he only remained married to Octavia because he was still under his mother’s control and under her influence, Nero orchestrated an accident that was meant to kill his mother. She survived the accident but was finally assassinated in her villa after she shouted at her attackers to aim for her womb where she had carried Nero.

Poppaea Sabina became pregnant with Nero’s child and Nero then finally divorced Octavia, marrying Poppaea Sabina just 12 days after the divorce. Nero and Poppaea Sabina had Octavia banished to the island of Pandateria on a false charge of adultery. Octavia had been a popular Empress with the people, and the citizens protested her treatment, openly parading with statues of her and calling for her return. When Octavia herself complained, her maids were tortured to death. This frightened Nero, but he became more determined to get rid of her.

Poppea brings the head of Octavia to Nero (public domain)

Poppea brings the head of Octavia to Nero (public domain)Nero ordered her death and on 8 June 62 AD, she was bound and had her veins opened in a traditional Roman suicide ritual. She was then suffocated in a hot bath. Her head was cut off and sent to Poppaea Sabina. She was still only around 22 years old.1

The post Claudia Octavia – The neglected Empress appeared first on History of Royal Women.

February 1, 2020

Kunigunda of Slavonia – A dowager Queen who took a lover

Most medieval dowager Queens were expected to live quietly and retire to a chaste and religious life after their husband’s death. Sometimes, if they were still young, they could remarry to a man of fitting rank. Kunigunda of Slavonia is an example of a queen who did neither of these things. Instead, she took a lover who was of lower rank.

Princess of Hungary and Kiev

Kunigunda of Slavonia was born around 1245, as a daughter of Rostislav Mikhailovich and Anna of Hungary. Her father was a Russian prince from the Rurik dynasty. He once was the prince of the Principality of Halych (in present-day Ukraine), but he had lost it by the time Kunigunda was born. Rostislav was descended from the Grand Princes of Kiev. After losing Halych, he fled to Hungary and married Anna, the daughter of King Bela IV of Hungary and Maria Laskarina. Anna was reportedly the King’s favourite daughter. Bela granted Rostislav territories in Hungary, making him Ban of Slavonia in 1247 and Duke of Macso in 1254. Rostislav claimed the title Tsar of Bulgaria in 1257 but was never recognised as its ruler.

Around the time of her birth, Kunigunda’s father was fighting for his lost territory of Halych. Not much is known about her early life, but perhaps she was raised at her grandfather’s royal court. Kunigunda is also known as Kuingunda of Halych or Kunigunda Rostislavna.

The Bohemian Marriage

The King of Bohemia at this time, Ottokar II, first married Margaret, heiress of Austria in 1252. At this time, Margaret was widowed, had no surviving children, and was about 48 years old – well past her childbearing years and about 26 years older than Ottokar. However, she was a desirable bride due to her claim to Austria. Margaret’s brother, Frederick II of Austria, the last male member of Austria’s ruling Babenberg dynasty, was killed in battle in 1246, leaving behind no children. Margaret, as the oldest sister of Frederick, was seen as a possible successor. The territory of Styria was attached to Austria. As the husband of Margaret, Ottokar claimed Styria, but Bela IV of Hungary also lay claim to Styria. In the end, Ottokar won a battle against the Hungarian King in July 1260 and added Styria to his territories.

But Ottokar still needed an heir to continue his dynasty, and his wife was past her childbearing years. With his mistress, a lady-in-waiting of Margaret, named Agnes, Ottokar had one son, Nicholas, and two daughters. Ottokar tried to get the Pope to recognise Nicholas as his heir, but this request was denied. This meant that Ottokar had to have a legitimate son in marriage, but in order to do so, he had to divorce Margaret and find a younger wife.

Ottokar looked towards Hungary for a new wife, seeing marriage as a perfect opportunity to confirm peace with Bela. First, Bela offered his only unmarried daughter, Margaret, who was previously promised to the church. Margaret refused and wished to remain a nun. So Bela chose his granddaughter, Kunigunda, instead.

Kunigunda and Ottokar were married on 25 October 1261 in Bratislava. Kunigunda was about 16, and closer to Ottokar’s age than Margaret. Two months later, Ottokar and Kunigunda were crowned in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. Ottokar had been King of Bohemia for eight years but was not previously crowned.

Queen of Bohemia

The marriage of Kunigunda and Ottokar turned out to be successful. In their seventeen years of marriage, Kunigunda bore between three and six children. Their first child was a daughter named after Kunigunda, born in January 1265. Two more surviving children followed, a daughter, Agnes in 1269, and a son, Wenceslaus in 1271. There may have been three other children who were short-lived. There are some mentions of two sons who died in infancy. They may also have had a daughter named Margaret, who died in 1277.

(public domain)

(public domain)While Kunigunda was bearing children, Ottokar was building an empire. Besides his inheritance of Bohemia and the Margraviate of Moravia, he still held on to his first wife’s territories of Austria and Styria. In 1269, he acquired the southern territories of Carinthia and Carniola. His realm now reached the Adriatic sea, but his empire would not last for long. Many of Ottokar’s lands lay within the Holy Roman Empire. When the Hohenstaufen dynasty, (who ruled the empire) died out, Ottokar was hoping to reach the imperial crown too. After all, his mother was from the Hohenstaufen dynasty. However, in 1273, a new and unlikely candidate was chosen instead – Count Rudolf of Habsburg. Ottokar saw the choice of Rudolf – a mere count – as a slap in the face and refused to acknowledge his election.

War soon broke out between Ottokar and Rudolf. Ottokar was forced to surrender Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola to Rudolf in 1276. During this time, Kunigunda would find herself torn between loyalties. Her uncle, King Stephen V of Hungary, and later her cousin, King Ladislaus IV of Hungary would go to war against her husband. Kunigunda nevertheless seemed to be a faithful wife during this time and stood by Ottokar.

On 26 August 1278, a fateful battle took place between Ottokar and Rudolf. This battle, known as the Battle on the Marchfeld, is surrounded in many myths, some which involve Kunigunda. Around this time, a Bohemian nobleman, Zavis of Falkenstein made his first notable appearance. One myth has Zavis betraying Ottokar on the eve of the battle. Some legends say that Kunigunda pushed her husband towards the battle. Other stories have Kunigunda and Zavis becoming lovers during Ottokar’s lifetime. These legends are not given serious credit. Zavis did, however, previously participate in a rebellion against Ottokar. Ottakar was killed in the Battle of the Marchfeld. His only surviving son, Wenceslaus, was not yet seven.

An Independent Widow

Bohemia fell into turmoil after Ottokar’s death. Since the new King was barely seven, Kunigunda acted as regent for him. However, her power was limited, and she only controlled Prague and the surrounding area. The main protector of the kingdom was Ottokar’s nephew, Otto V, Margrave of Brandenburg. Kunigunda seemed to look toward Otto for help at first. He soon occupied Prague Castle, causing Kunigunda and her children to flee. Kunigunda seemed disappointed with this and sought support from Rudolf of Habsburg instead. Shortly afterwards, marriages were contracted between their children. Wenceslaus was to marry Rudolf’s daughter, Judith, and Agnes was to marry his youngest son, Rudolf.

The disagreements between Kunigunda and Otto continued. In January or February 1279, Otto had Kunigunda and Wenceslaus taken in the night from Prague to Bezdez castle, when they were kept under close guard. Kunigunda managed to escape that summer, but she left Wenceslaus behind. The circumstances of her escape and her reason for leaving her son are not clear. Perhaps Kunigunda wanted to take care of the kingdom’s affairs but was unable to take her son with her at first. Soon after her escape, she gave her husband’s body a proper burial and then retreated to her dower lands. She may have also taken some steps to liberate her son during this time.

Around 1280, Kunigunda began an affair with the Czech nobleman, Zavis of Falkenstein. This created quite the outrage since he was of much lower rank than the Queen, and he had once rebelled against her late husband. Even though later legends had the affair starting during Ottokar’s lifetime, Kunigunda probably did not meet Zavis until after her husband’s death. Kunigunda and Zavis seemed to have allied together against Otto of Brandenburg. Kunigunda even had an illegitimate son by Zavis, named Jesek, born 1281 or 1282. During this time, they may have even married in secret.

In 1283, the government of Otto of Brandenburg ended in Bohemia, and Wenceslaus was freed from captivity. In May 1383, the eleven-year-old King returned to Prague, where he was met by his mother. Apparently, Kunigunda did not bring Zavis with her at first, because she did not want to shock her son. However, Zavis eventually joined Kunigunda and was introduced to the young King. Wenceslaus seems to have at first accepted Zavis into his family. Zavis was now the most powerful man in the kingdom.

Sometime after Wenceslaus’ return, he allowed Kunigunda and Zavis to marry openly. The exact date of the wedding is not known, but it appears to have happened in 1284 or early 1285. In January 1385, the marriage of Wenceslaus with Judith of Habsburg was consummated. Kunigunda attended the ceremony. Rudolf of Habsburg, however, was displeased by Kunigunda and Zavis’ relationship, so he took his daughter back to Germany for the next two years.

Kunigunda did not enjoy her new marriage for long. She died on 9 September 1285, aged about 40. She possibly died from tuberculosis. Kunigunda was buried in the Monastery of St. Agnes in Prague. Zavis continued ruling as regent for the king, but as Wenceslaus grew, their relationship weakened. In 1289, Zavis was arrested for high treason, and Wenceslaus had him executed in August 1290.1

The post Kunigunda of Slavonia – A dowager Queen who took a lover appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 31, 2020

Edith of Wilton – King Edgar’s saintly daughter

Edith of Wilton was born in 962 as the daughter of King Edgar the Peaceful and Wilfrida. Wilfrida had been living in the nunnery at Wilton Abbey when she was carried off by Edgar. They were married around 961.

According to William of Malmesbury, Wilfrida was a reluctant wife who, “did not develop a taste for repetitions of sexual pleasure, but rather shunned them in disgust.” Wilfrida returned to Wilton Abbey soon after the birth of their daughter. She was escorted there by Edgar and the court, and with great ceremony, Wilfrida and her young daughter laid aside their clothes and possession. Young Edith was credited with choosing a veil from the many splendid clothes laid out. Wilfrida probably received a large settlement, and her actions left King Edgar open for a new marriage.

Edith received her education from the nuns of Wilton Abbey, and her mother eventually became the abbess of the Abbey. She was probably well aware of her royal status and dressed like it. The Bishop of Winchester apparently once upbraided her on her clothes, and Edith responded that “a mind is by no means poorer in aspiring to God will live beneath a goatskin. I possess my Lord, who pays attention to the mind, not to the clothing.” When a servant dropped a lit candle into one of her chests of clothing, her fine furs and imperial purple clothes were found undamaged.

Edith is known to have painted and to have written her own prayers. She would have also known how to sew and to embroider, and she made a vestment for the church at Wilton. She had some comfort in the form of a “cauldron in which her bath was heated,” and she had her own private zoo at Wilton. Many of the animals there were reportedly so tame that they would eat out of her hand.

Edith was given the authority of Winchester, Barking and another religious when she was about 15, but she did not wish to be away from her mother. When her father died and was succeeded by her half-brother Edward, she dreamt that one of her eyes fell out, and she believed that her dream foretold Edward’s death. Edward was murdered after a reign of just three years.

In 978, Edith erected a church dedicated to Saint Denis, and the Archbishop of Canterbury (later Saint Dunstan) attended the consecration when he noticed how Edith crossed herself. He took hold of her right thumb and said, “Never shall this thumb decay.” Edith died on 16 September, probably in the year 984, when she was about 23 years old. Her body was placed in the church of Saint Denis, and her thumb was later found to incorrupt. It was later enshrined separately.

Wilfrida survived her daughter for about 13 years, and she was present when Edith was elevated to sainthood.1

The post Edith of Wilton – King Edgar’s saintly daughter appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 30, 2020

The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The birth of Princess Beatrix

On Monday morning 31 January 1938 Queen Wilhelmina’s first grandchild, the future Queen Beatrix, was born at Soestdijk Palace. She was given the names Beatrix Wilhelmina Armgard, for both her grandmothers. She weighed eight pounds and was 52 centimetres long. Her parents were Queen Wilhelmina’s only surviving child Princess Juliana and her husband, Prince Bernhard. She was baptised on 12 May 1938. Her five godparents were King Leopold III of Belgium, Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone; Elisabeth, Princess of Erbach-Schönberg, Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg, and Countess Allene de Kotzebue.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Shortly before the start of the Second World War, she was joined in the nursery by a younger sister named Princess Irene. It soon became clear that the Netherlands would not be able to stay neutral during this war as it had been during the First World War. The night before the invasion, Queen Wilhelmina joined Juliana and her two granddaughters in a bomb shelter near Huis ten Bosch. On 13 May, the family boarded the HMS Hereward and were evacuated to the United Kingdom. Queen Wilhelmina set up a government in exile while Juliana, Beatrix and Irene were sent to Lydney Park in Gloucestershire. Soon there were plans to move them to Canada where they would be safer.

Meanwhile, Princess Irene’s baptism took place in the Royal Chapel of Buckingham Palace. On 2 June 1940, Juliana and her two daughters left for Canada on the Sumatra – arriving there on 10 June. Beatrix’s father Prince Bernhard remained in England.

In 1942, Queen Wilhelmina visited her family in Ottowa, where she was also joined by President Roosevelt, his wife and Princess Märtha of Sweden, Crown Princess of Norway. Beatrix and Irene stole the show, and Roosevelt’s secretary later wrote, “Princess Beatrix gave me some cherries from her basket, and the other little toddler gave me a posy. Really adorable children and great favourites with all the men on duty here.”1 Queen Wilhelmina then travelled on to the United States where she would address a joint session of the United States Congress. In early 1943, a third daughter named Margriet was born to Princess Juliana in Canada. The three little Princesses all learned to speak English with a Canadian accent. During their time in Canada, Beatrix attended nursery and Rockcliffe Park Public School, where she was known as “Trixie Orange.”

After a visit in August 1945, Queen Mary wrote, “Such talkative children, too funny, the baby (Margriet) climbing all over the furniture… They told us all about the ship Queen Mary… all in broad Canadian English.”2

Embed from Getty Images

On 2 August 1945, the family was finally able to return to the liberated Netherlands. They went to live at Soestdijk Palace, where Beatrix had been born. Beatrix continued her education at De Werkplaats in Bilthoven. A fourth and final daughter – Marijke Christina (later just Christina) was born to Princess Julia in 1947, but she suffered from limited eyesight after her mother had become infected with rubella during her pregnancy. More changes were to come when her grandmother Queen Wilhelmina abdicated on 4 September 1948 and Beatrix was now the heir to the throne.

Embed from Getty Images

Meanwhile, her education went ahead as planned. In 1950, she went to the Incrementum, part of the Baarns Lyceum, from which she graduated in 1956. She then attended Leiden University, where she studied Law, and she gained her degree in 1961.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Beatrix’s engagement to German diplomat Claus von Amsberg was announced on 28 June 1965 by her mother and father. They were married on 10 March 1966 and despite protests on their wedding (due to him being German) but he eventually became one of the more popular members of the royal family. They had met at the wedding of Princess Tatjana of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg and Moritz, Landgrave of Hesse. The newlyweds went to live at Drakensteyn Castle, and they went on to have three sons together: the current King Willem-Alexander (1967), Prince Friso (1968–2013) and Prince Constantijn (1969). They lived at Drakensteyn Castle until the abdication of Beatrix’s mother Juliana in 1980 when they moved to Huis ten Bosch.

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

Embed from Getty Images

On 30 April 1980, Beatrix became Queen of the Netherlands when her mother abdicated in her favour. She was inaugurated at a ceremony held in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam later that day. She would go on to reign as Queen for 33 years. Tragically, she lost her husband in 2002 after a long illness. Both her father and mother followed in 2004. She celebrated her silver jubilee in 2005 and received an honorary doctorate from the Leiden University that same year.

Embed from Getty Images

On Queen’s Day – the traditional birthday celebrations of the monarch – in 2009, there was an attack on the bus that the royal family were riding in. A man in a car crashed through a crowd of people – killing 8 (including the attacker) – but he missed the bus and crashed into a monument. The royal family was not hurt but witnessed much of the attack. A visibly emotional Queen Beatrix addressed the nation via live television a few hours later.

Embed from Getty Images

On 28 January 2013, Beatrix announced her intention to abdicate and she did so on 30 April 2013 – becoming the third successive monarch to abdicate. Prime Minister Rutte paid tribute to her saying, “Since her investiture in 1980, she has applied herself heart and soul to Dutch society.” The inauguration of her son – now King Willem-Alexander – took place in the afternoon on 30 April. Just a few months later, her middle son Prince Friso died of complications after being in a coma following an avalanche accident.

Beatrix with her grandchildren (© RVD – Jeroen van der Meyde)

Beatrix with her grandchildren (© RVD – Jeroen van der Meyde)Queen Beatrix reverted to using the title of Princess, and despite abdicating, she is still an active member of the royal family. Through her three sons, she has eight grandchildren.3

The post The Year of Queen Wilhelmina – The birth of Princess Beatrix appeared first on History of Royal Women.

January 29, 2020

Lucrezia Borgia – A Renaissance Duchess (Part two)

Lucrezia’s long train now headed north in horrible winter weather, and they finally made their entry into the city of Bologna on 29 January 1502. On 31 January, they arrived at Bentivoglio, where she finally but unexpectedly met her husband, and she was pleasantly surprised. They continued towards Ferrara by water. Upon her arrival in Ferrara on 2 February, a chronicler described her: “She is the most beautiful of face, with vivacious, laughing eyes, upright in her posture, acute, most prudent, most wise, happy, pleasing and friendly.” They were married in person with a consummation that same night. They were pleased with each other, but this did not stop Alfonso from returning to his other women. She made a good impression in Ferrara, except with her sister-in-law Isabella who considered Lucrezia to be beneath her.

Lucrezia soon found herself pregnant again, and she suffered from a lack of appetite and was unwell. As the summer dragged on, she became more unwell, and in the middle of July, an epidemic fever reached Ferrara. She began to suffer paroxysms with fever and Alfonso spent the nights in the room next to hers. On 31 July, the consensus was that Lucrezia and her child would die, and she suffered a severe nosebleed. Yet, she survived throughout August until she suddenly suffered a convulsion on 5 September, and she went into labour. She gave birth to a stillborn daughter and was affected by puerperal fever. She was bled two days later with Cesare by her side, trying to make her laugh. She continued to hover between life and death until early October when she finally rallied.

On 18 August 1503, Lucrezia’s father died, and she was devastated. He was followed by Pope Pius III, who died after a reign of just 26 days. He was succeeded by Pope Julius II – born Giuliano della Rovere – an enemy of the Borgias. On 17 November 1503, a new pregnancy was reported for Lucrezia, but she miscarried sometime in the following year. Like her husband, Lucrezia began to embark on affairs.

Ercole died on 25 January 1505 after a short illness, and they were now the reigning Duke and Duchess. On 19 September 1505, Lucrezia gave birth to a son named Alexandro, but he was a sickly child who refused to take the breast. Tragically, he died on 16 October 1505 after suffering from fits and convulsions. She was pregnant again by early 1507, but she miscarried in mid-January much to Alfonso’s despair, who believed she had brought it on herself with her partying. Lucrezia too was very upset “by this disaster of hers.” On 12 March 1507, Lucrezia’s brother Cesare was killed in an ambush in Navarre. Lucrezia did not learn of his death until six weeks later. She reported cried, “The more I try to please God, the more he tries me…”

On 7 November 1507, another pregnancy was reported, and on 5 April 1508, Lucrezia gave birth to a son named Ercole – in honour of his grandfather. The boy seemed healthy and likely to live. Lucrezia had done her duty as Duchess. As her husband headed to war at the end of 1508, Lucrezia was basically the ruler of Ferrara for the next few years. He had left her pregnant, though, and she gave birth to a second son named Ippolito on 25 August 1509. Her husband’s absence probably gave her body some much-needed rest.

In August 1512, Lucrezia received the news of the death of her son by Alfonso of Aragon. He had died at the age of 12, and she had not seen him since he was two years old. She spent a month at the convent of San Bernardino in mourning. On 1 October, she wrote of “finding myself completely overcome with tears and bitterness for the death for the Duke of Bisceglie, my most dear son…”

At the end of 1512, Lucrezia was reunited with her husband, and between then and 1518, she would give birth to three more children. Alexandro was born in April 1514, but he died in 1516. Leonora was born on 4 July 1515 and Francesco was born on 1 November 1516. Her many pregnancies by her syphilitic husband had weakened her and eventually, in 1519 came one final, fatal pregnancy.

By May, she was very weak and unable to eat. Alfonso spent a lot of time by her side. On 14 June, Lucrezia gave birth to a weak baby girl who refused to eat until the following day. Alfonso had the baby christened straightaway, naming her Isabella Maria. Lucrezia had a fever but appeared well otherwise. However, her condition soon deteriorated. She suffered fits, was bled, and her hair was cut off. On 20 June, she suffered a nosebleed. She became unable to speak and could no longer see. She then appeared to improve slightly, and it was believed that she would survive.

Lucrezia did not believe she would survive and dictated a letter to Pope Leo X:

“Most Holy Father…

With every possible reverence of spirit, I kiss the holy feet of Your Beatitude and humbly recommend myself to the grace of Your Holiness. Having suffered greatly for more than two months because of a difficult pregnancy, as it has pleased God on the 14th of this month at dawn, I had a daughter, and I hoped that having given birth my illness also must be alleviated, but the most contrary happened so that I must yield to nature. Our most clement Creator has given me so many gifts that I recognise the end of my life and feel that within a few hours, I shall be out of it, having, however first received all the holy sacraments of the Church. And at this point, as a Christian, although a sinner, it came to me to beseech your Beatitude that through your benignity you might deign to give from the spiritual Treasury some suffrage with your holy benediction to my soul. And thus devotedly, I pray you, and to your grace, I commend my lord Consort and my children, all servants of your Beatitude.”

Yet, Lucrezia held on for two more agonising days, dying on 24 June 1519. Her husband wrote, “I cannot write without tears, so grave is it to find myself deprived of such a sweet, dear companion as she was to me, for her good ways and for the tender love there was between us.” Lucrezia was buried in the convent of Corpus Domini, where she was later joined by her husband. Her young daughter Isabella would die at the age of 2.1

The post Lucrezia Borgia – A Renaissance Duchess (Part two) appeared first on History of Royal Women.