Moniek Bloks's Blog, page 131

December 3, 2021

Xijun – The isolated Princess

Princess Xijun’s marriage was known to be the first recorded marital alliance in Han history. However, she led a tragic life. Although she was from the imperial family, she was forced to live a life of slavery. However, Emperor Wudi chose her for the important task of marrying her to the King of Wusun. This alliance was meant to protect Han China from the raiding Huns. Yet, the marriage often left Princess Xijun lonely. This inspired her to create a poem detailing her sorrow. This poem has moved Chinese people’s hearts for centuries. It shows the reader the mind of a sorrowful princess who is forced to leave her home.

Princess Xijun was born around 124 B.C.E. Her family was of imperial lineage.[1] Her great-grandfather was Emperor Jing.[2] Her grandfather was Liu Fei, the brother of Emperor Wudi.[3] Her father, Liu Jian, became the Prince of Jiangdu.[4] He had several wives and concubines.[5] Historical records describe Liu Jian as “brutal, incestuous, and depraved”.[6]

When Liu Xijun was an infant, her father was accused of leading a rebellion against the royal family and was forced to commit suicide.[7] In that same year, her mother was publicly executed for witchcraft.[8] Because her parents were public criminals against the nation, Liu Xijun and her siblings were forced to be slaves in the palace.[9]

In 105 B.C.E., Emperor Wudi created a marriage alliance with Lie Jiaomi, the King of Wusun.[10] Wusun were an Indo-European people that inhabited the modern-day Lake Balkhash region and northwestern Xinjiang.[11] The population consisted of 630,000 (which was tiny compared to Han’s population of 58 million people).[12] This alliance would compel the King of Wusun to help China against the raiding Xiongnu (known to Western readers as the Huns).[13] Emperor Wu chose his great-niece, Liu Xijun and believed that she was the perfect Han ambassador for Wusun. Emperor Wudi officially made her his granddaughter and gave her the title of Princess.[14] King Lie Jiaomi gave Emperor Wudi 1,000 horses for his betrothal gift.[15] Then, Princess Xijun, who was accompanied by her entourage of several hundred officials, eunuchs, and servants, embarked on a 3,000-mile journey from Chang’an to Wusun.[16]

When Princess Xijun finally arrived in Wusun, she discovered that the Xiongnu also sent their Princess to marry the King of Wusun.[17] The King of Wusun married both of them, but he preferred the Xiongnu princess. He made the Xiongnu princess the Lady of the Left.[18] Princess Xijun was made Lady of the Right, which was of lesser status than the Lady of the Left.[19]Princess Xijun’s marriage to the King of Wusun was very unhappy. She did not know the language and could not communicate with her husband.[20] Thus, she only saw him twice a year on special occasions.[21]

Princess Xijun could never get used to living in Wusun. She disliked living in a yurt house and built her own palace that resembled Chinese architecture.[22] She did not like eating raw meat and cheese.[23] Thus, she decided to spread Han culture throughout the region.[24] Yet, she was still lonely and yearned to be home. She is credited to have written the poem that is recorded in The History of Han China:

“I was forced to marry Wusan

Who lives in a land far away from Han,

Sheltered in the yurt, eating raw meat and cold cheese,

I suffered from homesickness and sadness,

If only I could fly like a swan, back to my homeland.”[25]

This poem was sent to Emperor Wudi. The poem moved Emperor Wudi greatly, and he sent gifts to console his adopted granddaughter every other year.[26]

When Lie Jiaomi was dying, he wanted her to marry his grandson.[27] His grandson, Jun Xumi, would be the next King of Wusun, and he wanted the marriage alliance between the two nations to continue.[28] Princess Xijun was horrified and repulsed when she learned that she had to marry her step-grandson.[29] This was considered incestuous in Han China.[30] She protested against the marriage and asked Emperor Wudi to intervene. However, Emperor Wudi instructed her to follow Wusun’s customs and marry the new King.[31] Emperor Wudi still saw the importance of the marriage alliance.[32]

Reluctantly, Princess Xijun married Jun Xumi, the next King of Wusun. She bore him a daughter named Shaofu.[33] Five years after she had arrived in Wusun, she died in 101 B.C.E.[34] Since Princess Xijun did not produce a son, Emperor Wudi sent another princess, Jieyou, to take her place.[35] Thus, while Princess Xijun spent a short time in Wusun, she made contributions to China. Her story tells us how the Han dynasty used marriage alliances to maintain peace with other nations.[36] Princess Xijun’s poem was her greatest contribution.[37] For in her tale, we see a sorrowful princess that was forced to become a political pawn in order to fulfil Han China’s ambitions.

Sources:

Fanzhong, Y. & Peterson, B. (2015). Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century (B. B. Peterson, Ed.; C.Jun, Trans.). London: Routledge.

Jay, J. (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E. – 618 C.E. (L. X. H. Lee, Ed.; A. D. Stefanowska, Ed.; S. Wiles, Ed.). NY: Routledge.

Wright, D.C. (2011). A Chinese Princess Bride’s Life and Activism Among the Eastern Turks, 580=590 C.E.. Journal of Asian History, 45(1/2), 39–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41933579.

[1] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 66

[2] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 66

[3] Jay, p. 168

[4] Wright, p. 40

[5] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 66

[6] Jay, p. 168

[7] Jay, p. 168

[8] Jay, p. 168

[9] Jay, p. 168

[10] Jay, p. 168

[11] Wright, p. 40

[12] Jay, p. 169

[13] Jay, p. 169; Wright p. 40

[14] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 66

[15] Jay, p. 169

[16] Jay, p. 169

[17] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 67

[18] Jay, p. 169

[19] Jay, p. 169

[20] Wright, p. 40

[21] Jay, p. 169

[22] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 67

[23] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 67

[24] Fanzhong & Peterson p. 67

[25] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 67

[26] Jay, p. 169; Wright, p. 41

[27] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 67

[28] Jay, p. 169

[29] Jay, p. 169

[30] Jay, p. 169

[31] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 67

[32] Jay, p. 169

[33] Jay, p. 169

[34] Jay, p. 169

[35] Jay, p. 169

[36] Fanzhong & Peterson, p. 68

[37] Jay, p. 169

The post Xijun – The isolated Princess appeared first on History of Royal Women.

December 2, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis flees to France

At the end of October 1936, as the ‘King’s matter’ was close to becoming public, Wallis received a letter from her friend Herman Rogers promising his friendship and a way out. He wrote, “We are with you always… Come to us if and when you can – or call us if you want us.” 1 She would take him up on his offer sooner than expected.

The King had already told his Prime Minister that he was prepared to go, and Wallis had begged him to let her go abroad. Wallis later wrote, “In the weeks before the abdication, I was willing to do anything – anything – to prevent his going. I lied to our friends, I lied to the King – all in the hope that someone would put a stop to it.” 2 A morganatic marriage proposal was floated, but it had no precedent, and legislation would be needed.

On 27 November, feeling ill with the strain, Wallis and her aunt Bessie left London for Fort Belvedere. On 30 November, she wrote to her friend Sibyl, “I am planning quite by myself to go away for a while. I think everyone here would like that – except one person perhaps – but I am planning a clever means of escape. After a while, my name will be forgotten by the people, and only two people will suffer instead of a mass of people who aren’t interested anyway in individual feeling but only the workings of a system.”3

On 3 December, the storm broke, and the newspapers were full of the issue. Wallis later wrote, “I was braced for a blow, but nothing had equipped me to deal with what faced me on my breakfast tray in the morning.” 4 The King now finally agreed that she should leave the country, and Wallis telephoned Herman Rogers in France. Arrangements were quickly made for her to travel to the Rogers’ villa in Cannes. She was to go to Cannes with the King’s Lord-in-waiting Lord Brownlow and Inspector Evans of Scotland Yard, leaving behind aunt Bessie and her dog Slipper. As Wallis packed her things, the King did the last thing he could think of to stay on the throne – he wrote a speech intended to appeal to his people.

In the late afternoon, Wallis’ suitcases were loaded into two cars. She later wrote, “Hurried as were my last moments at the Fort, they were nonetheless poignant. I think we all had a sense of tragedy, of irretrievable finality. As for me, this was the last hour of what had been for me the enchanted years. I was sure I would never see David again.” 5 At the front door of the Fort, Wallis hugged her aunt Bessie and then turned to the King, who took her in his arms. He said, “I don’t know how it’s all going to end. It will be some time before we can be together again. You must wait for me no matter how long it takes. I shall never give you up.” As Wallis climbed into the car, the King reached through the window to touch her hand and told her, “Bless you, my darling!” 6

Wallis boarded the ferry at Newhaven under the name Mrs Harris, but customs’ officials quickly learned of her real identity, and within a matter of hours, the French press had learned of her arrival. From Dieppe to Cannes, Wallis and the press played a game of cat and mouse. At 2 in the morning, they stopped at a hotel in Rouen where a frightened Wallis begged Lord Brownlow to leave the door between their rooms open. She then began to sob and begged him to sleep in the other bed. He later recalled, “Sounds came out of her that were absolutely without top, bottom… that were primaeval. There was nothing I could do but lie down beside her, hold her hand, and make her feel that she was not alone.”7

As they made a run for the car the following morning, the lobby was already filled with people. An altercation ensued, and the Inspector smashed a camera. Their next stop was in Evreux, where Wallis called the King. However, the line was so bad that Wallis had to shout down the receiver to make herself heard. She begged him not to abdicate, but the King was distant. That night they slept in a hotel in Blois where the lobby quickly filled up with reporters. Lord Brownlow told them they would leave at nine the following morning, but the intention was to leave at dawn. He woke Wallis up at 3 in the morning, and they quietly crept out of the hotel. Despite this, wherever she travelled, her car was followed by several cars with members of the press. After stopping at a cafe to once again call the King, she was forced to climb out a first-floor window to avoid the press.

At 2.30 in the morning of 6 December, as Wallis lay on the floor of the car covered with a rug, the car pulled through a mob of reporters into the grounds of the Rogers’ villa. Herman and his wife Katherine were waiting at the front door and quickly pulled her inside. She was safe at last.

She wrote to the King that very same day, “I am so anxious for you not to abdicate and I think the fact that you do is going to put me in the wrong light to the entire world because they will say that I could have prevented it.”8

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – Wallis flees to France appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 30, 2021

Film Review: Spencer

A fable from a true tragedy.

The new Spencer film sums itself up quite nicely before it has even begun. It centres around three days of Christmas at Sandringham with the royal family and during which Diana decides to leave Charles.

I went in with quite negative expectations, based on other people’s experiences of seeing the film. However, I found myself rather enjoying Kristen Stewart as Diana, as she has undoubtedly evolved from her Twilight days. The film focuses heavily on Diana’s internal struggles and her fight against bulimia, and the images are rather raw and leave an impression. The downside of this is that there is very little interaction with the family, except for her sons and Charles. I think it would have been interesting to see more of this. Diana’s internal struggles are also emphasized by the intense music that accompanies the film. I found the music to be rather distracting and even took away from the story, which is a shame.

Nevertheless, with its beautiful sets and a wardrobe of dreams, Spencer becomes a nightmarish fairytale. It has its ups and downs, and I have rather mixed feelings about the whole thing. Perhaps this is just one of those films that you either love or hate.

Spencer is now in cinemas. For more release dates, go here.

The post Film Review: Spencer appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 28, 2021

Margaret of Navarre – Medieval Sicily’s most powerful Queen (Part one)

For several years, Margaret of Navarre, Queen of Sicily, was the most powerful woman in the Mediterranean. Then, widowed in 1166, with a 12-year-old son as the new King, she became regent. But the notable events in her life did not start there. During her time as queen consort, it was clear that she was an influential woman.

Early life

Margaret was born around 1135, to King Garcia Ramirez IV of Navarre, and Marguerite de l’Aigle. Her father became King of Navarre just a year prior to her birth. She had a sister, Blanche, who married Sancho III, King of Castile, and two brothers, Sancho VI, King of Navarre, and Rodrigo, also known as Henry. Margaret’s mother was accused of adultery in 1139, and Garcia refused to acknowledge Rodrigo, who was born that year, as his own son. The disgraced Queen Marguerite died just two years later.

Duchess of Apulia

In 1148, ambassadors from Sicily arrived in Navarre to negotiate a marriage between Margaret and William, the son and heir of Roger II, the King of Sicily. Margaret’s father agreed to this marriage. In the late spring of 1149, Margaret left for her new life in Sicily. Margaret and her entourage travelled through Aragon and Catalonia and the southern French coast. Around Nice, she boarded a ship that took her to Sicily. In the summer of 1149, Margaret arrived in Palermo, Sicily, where she met and married William, Duke of Apulia.

At the time, it was common for kings to crown their eldest sons as junior or co-kings to ensure a smooth succession. In April 1151, William was crowned junior King. Margaret was thus now a queen consort. For some time, she was the only queen consort in Sicily until the twice-widowed Roger II married Beatrice of Rethel later that year.

During these early years, Margaret proved to be a fertile wife. She gave birth to three sons in quick succession; Roger in 1152, Robert in 1153, and William in 1154.

Queen Consort

Roger II died in February 1154. William and Margaret were crowned as King and Queen of Sicily in Palermo on Easter of that year. Their eldest son, Roger, was made Duke of Apulia, the title for the heir apparent of Sicily. At his succession, William appointed Maio of Bari as his chancellor.

Unfortunately, William would not prove as strong a king as his father, and his reign was filled with many rebellions and conspiracies. The first conflict of his reign was an attempted invasion of Sicily by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, aided by the Byzantine Emperor Manuel and encouraged by the pope, Adrian IV. The planned invasion of the Holy Roman Emperor came to nothing, but the Byzantine Emperor was still launching attacks on Sicily. In addition, rebellions were also breaking out. Finally, in the spring of 1156, William was able to quash the rebellions and disprove those who had underestimated him. Margaret seems to have been a loyal wife to William during this time.

In 1158, Margaret gave birth to a fourth son, Henry. The second son, Robert, was named Prince of Capua, a title used for the second sons of the kings of Sicily. Having borne four sons, Margaret now seemed to be a respected queen consort. While William and his chancellor Maio were absent from Palermo for long periods of time, the people of the city looked to Margaret for leadership. In 1159, Margaret welcomed her cousin, Gilbert of Perche, to Sicily, and he was soon created as Count of Gravina.

Tragedy struck in late 1159, when Margaret’s second son, the six-year-old Robert, died of an illness. Around this time, another plot against the King was growing. The main target in this plot was the chancellor, Maio. This plot was led by the powerful baron, Matthew Bonello. In November 1160, Bonello assassinated Maio. The King and queen were quickly informed about what had happened and were obviously angry about it.

A coup against the King

Margaret grew more and more suspicious about Bonello. He soon was invited to court less frequently. Bonello believed that the King was trying to marginalize him and that Margaret had supported this. Bonello soon began to conspire with other nobles against the King. Among them were two illegitimate members of William’s family, the House of Hauteville. They were Simon, William’s half-brother, and Tancred, Count of Lecce, an illegitimate nephew of the King. Margaret’s cousin, Gilbert of Perche, also joined the plot.

In March 1161, Bonello and his co-conspirators set out on their plan to attack the royal palace in Palermo. They were even aided by the palace’s castellan, who controlled the entrances. In addition, Simon, who had grown up in the palace, was familiar with its layout.

On the morning of 9 March, Margaret, William, and their children were at mass in the palace’s chapel. The conspirators saw this as the perfect time to enter the palace. First, they reached the dungeon and freed all of the prisoners. After mass, Margaret and the children headed to the royal apartments for the day’s lessons, and William headed to his chamber with a couple of his advisors. While heading down the corridor, William was crossed by an armed group of men, which included Simon and Tancred, whom he previously denied entrance to the palace. With them were the noblemen who had just been freed from the dungeon. Outnumbered, William and his advisors tried to flee but were caught by the rebels. They then demanded that William abdicate.

The rebels placed William under guard in one of the rooms and proceeded to loot the palace. They found Margaret, the children, and some servants in a room together and made sure that they would not escape. The rebels then proceeded to attack the city of Palermo, killing shopkeepers and tax collectors and burning records, such as tax rolls.

Bonello, Simon, and Tancred wanted to replace William with a king they could control. They reached the room where Margaret and her children were taking shelter and demanded that she hand over her eldest son, nine-year-old Roger. Having no choice, Margaret gave in to this request. The rebel leaders proceeded to dress Roger in royal robes and led him around Palermo, proclaiming him as the new King. They did the same with Roger the next day. This failed to satisfy everyone, and many believed that William should remain King.

Two days after the coup started, a large group of local men stormed the palace and threatened to besiege it unless the rebels freed William. The conspirators eventually gave in, and William promised them safe conduct if freed. However, sometime during the commotion, a stray arrow hit Prince Roger, who was standing near a window. He died soon afterwards. The crisis soon ended, but Margaret was devastated that she had lost a second child. Another theory of Roger’s death says that William, enraged at Roger’s role in the coup, repeatedly kicked him until he died. This story, however, seems to be made up by William’s enemies.

Bonello still wanted to overthrow the King and marched towards Palermo. He was eventually arrested, blinded, and thrown into a dungeon, where he died later that same year. William exiled Tancred and Simon while Margaret’s cousin Gilbert was pardoned for his role in the revolt at her own urging.

William’s Later Reign

After the revolt, Margaret was one of the few people whom William could trust. After it, he more frequently turned to her for counsel. In early 1162, William travelled through Sicily and onto the mainland portion of the kingdom to put down some disturbances. Margaret stayed behind and governed Palermo until his return that summer. One of Margaret’s primary advisors was an Arab eunuch named Martin, who converted to Catholicism.

In March 1166, William came down with dysentery. Fearing that he was dying, he set out his plans for succession. His eldest surviving son and namesake was named as his heir. Since the boy was only twelve years old, he put together a group to rule until he came of age. This included his trusted counsellors, Richard Palmer and Matthew of Aiello. As for Margaret, she was named as “keeper of the entire realm”, which meant she was regent. King William I of Sicily died on 7 May 1166. His twelve-year-old son, William II, succeeded to the throne, with Margaret as his regent.1

Part two coming soon.

The post Margaret of Navarre – Medieval Sicily’s most powerful Queen (Part one) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 26, 2021

The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The wedding celebrations of the Kents

From their first meeting on 10 January 1931, Wallis Simpson slowly rose to become the Prince of Wales’ favourite.

In early 1932, Wallis and Ernest entertained the Prince in their flat at Bryanston Court for the first time. He stayed until 4 a.m. and even asked for one of her recipes. At the end of January, they were also invited to spend the weekend with him at Fort Belvedere. Wallis was surprised to find him doing needlepoint. He told her, “This is my secret vice, the only one, in any case, I am at any pains to conceal.”1 Wallis also received a private tour of the grounds from the Prince. Over the coming year, they received regular invitations to the Fort, partly because Thelma was afraid of losing the Prince and she wanted to surround him was amusing guests.

In January 1933, Wallis found herself on ice skates alongside Thelma and the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King George VI and Queen Elizabeth). She also became acquainted with Prince George, later the Duke of Kent. She began the year 1934 celebrating with the Prince until 5 a.m, followed by dinner later that day, also with the Prince. Then came the trip that changed everything – Thelma was leaving for a trip to the United States, and according to Wallis, she asked, “I’m afraid the Prince is going to be lonely. Wallis, won’t you look after him?”2 According to Thelma’s memoirs, it was Wallis who initiated the topic with the words, “Oh, Thelma, the little man is going to be so lonely.” To which Thelma replied, “Well, dear, you look after him for me while I’m away.”3 Thelma sailed on 25 January 1934 – paving the way for Wallis to rise from friend to favourite.

The Prince began visiting her home several times a week, and Ernest was surprisingly tolerant of the entire situation. He found ways to excuse himself as Wallis and the Prince talked until the small hours. On 12 February, Wallis wrote to her aunt, “I am sure the gossip will now be that I am the latest.” However, she was already a bit exasperated and ended the letter with, “Forgive me for not writing, but this man is exhausting.|4 On the 18th, she wrote, “It’s all gossip about the Prince. I am not in the habit of taking my girlfriends’ beaux.”5

The following Easter weekend was spent at the Fort with Thelma and the Simpsons. Thelma wrote, “At dinner, however, I noticed that the Prince and Wallis seemed to have little private jokes. Once he picked up a piece of salad with his fingers, Wallis playfully slapped his hand… Wallis looked straight at me. And then and there, I knew the ‘reason’ was Wallis… I knew then that she had looked after him exceedingly well. That one cold, defiant glance had told me the entire story.”6

Wallis was now firmly in place as the new favourite and this was confirmed when Wallis and Ernest were invited to the wedding of Prince George to Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark in November 1934. Prince George lived at Fort Belvedere as he prepared for his wedding, and so Wallis saw quite a lot of him during this time and even went to the theatre with him. Wallis sarcastically wrote to her aunt, “I do well with the Windsor lads.”7

Two days before the wedding, a reception took place at Buckingham Palace, to which Wallis and Ernest were also invited. King George and Queen Mary were by now well aware of their son’s interest in Wallis, and it was reportedly on this occasion that they ordered her name to be crossed off the guest list. The Prince of Wales reportedly told his parents that “if he were not allowed to invite these friends of his, he would not go to the ball. He pointed out that the Simpsons were remarkably nice Americans, that it was important England and America be on cordial terms, and that he himself had been most kindly entertained in the States. His parents gave way, and the Simpsons duly came to the ball.”8

For the ball, Ernest wore black knee-breeches, and Wallis wore a violet lamé dress with a green sash and also borrowed a tiara from Cartier for the occasion. Wallis wrote, “We took our places in the line of guests that by custom forms on either side of the reception rooms on the approach of the Sovereign and his Consort. As they proceeded with great dignity down the room, members of the Royal party followed in their wake, stopping now and then to speak with friends. The Prince of Wales brought Prince Paul, Regent of Yugoslavia and also brother-in-law of the bride, over to talk with us. ‘Mrs Simpson,’ said Prince Paul, ‘there is no question about it – you are wearing the most striking gown in the room.’ [..] The reception was rendered truly memorable for me the reason that it was the only time I ever met David’s father and mother.9 After Prince Paul had left us, David led me over to where they were standing and introduced me. It was the briefest of encounters – a few words of perfunctory greeting, an exchange of meaningless pleasantries, and we moved away. But I was impressed by Their Majesties great gift for making everyone they met, however casually, feel at ease in their presence.”10

Embed from Getty ImagesTwo days later, the royal wedding took place at Westminster Abbey, and Wallis thought the ceremony had been very solemn and moving. They had been seated on a side aisle from which they had a clear view of the altar. Wallis later wrote, “It seemed unbelievable that I, Wallis Warfield of Baltimore, Maryland, could be part of this enchanted world. It seemed so incredible that it produced in me a dreamy state of happy and unheeding acceptance.”11

The post The Year of the Duchess of Windsor – The wedding celebrations of the Kents appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 25, 2021

Maria Theresa of Austria – ‘No equal amongst the sovereigns of this century’ (Part five)

Marie-Antoinette was receiving a crash course in basically everything she needed to know as Queen of France, but she continued to be “unruly” and “tomboyish”, much to her mother’s horror. However, we cannot forget that she was still only 15 years old.1 On 19 January 1770, Marie Antoinette married the Dauphin of France in a proxy ceremony in Vienna. Maria Theresa walked her daughter down the aisle where her brother Ferdinand stood in for the groom. She left Austria forever the following day. Maria Theresa clasped her youngest daughter in her arms and whispered to her, “Farewell, my dearest child, a great distance will separate us… Do so much good to the French people that they can say that I have sent them an angel.”2

On 15 October 1771, Maria Theresa’s second youngest son Ferdinand married heiress Maria Beatrice d’Este, and together they became the founders of the House of Austria-Este. He would be the last of her children to marry. Her youngest son Maximilian Francis became Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. As her children left, their families grew, Maria Theresa’s became a grandmother many times over. While Joseph remained unmarried, Leopold and his wife went on to have a total of 16 children, though not all of these would survive to adulthood. Leopold took great pains to convey to his children that they were there to serve the people. He told his children’s tutor, “The princes must be very aware that they are human beings: that they hold their positions only through the sanction of other human beings; that for their part they must discharge all their duties and cares; and that the other people must have the right to expect all benefits that have been granted to them… True greatness is broad, gentle, familiar, and popular, it loses by being seen at close quarters.”3

As her grandchildren were growing up, Maria Theresa’s health began to decline slowly. She wrote, “My hands and my eyes are failing; I shall no longer be able to write to you but by the hand of another.”4 She began feeling overwhelmed trying to reign with her declining health. The following crisis in Poland and disagreements with her son Joseph left her feeling drained. Leopold described the relationship between his mother and brother, “When they are together, there is [sic] unbroken strife and constant arguments… even in the smallest affairs; they are never of the same opinion and fight each other constantly over matters worth nothing.”5

Maria Theresa was also very worried about Maria Antoinette in France. After four years of marriage, she was still not pregnant, but with the death of King Louis XV, she now became Queen of France. At the time, their popularity was probably at a high point, and their tragic fates were still two decades away. Maria Theresa decided to ask Joseph to do something, and so Joseph went to France. He spent six weeks in France, and his visit seemed to have worked. In early 1778, Maria Antoinette was finally pregnant. A healthy baby girl was born in December. She was Maria Theresa’s 25th grandchild.

During the last year of her life, Maria Theresa was often lonely. Joseph had basically abandoned his mother and Vienna, but luckily she was quite close to many of her grandchildren. She spent her days with her state papers, visited her husband’s grave every day and even had a chair brought into the crypt so that she could spend hours there. However, she knew her life was coming to an end.

In early November 1780, she participated in the annual family pheasant hunt and caught a terrible cold. In just a few days time, she was having chest pains and had difficulty breathing. She struggled for several weeks as the family gathered around her. Finally, feeling the end near on 29 November, she told Joseph, “God has asked for my life. I feel it.”6 She refused to take any medication to ease her suffering and remained clear-headed in her final hours. She spoke of successes, failures and children. She soon found it too difficult to breathe lying down and asked Joseph to help move her to a couch. He helped her but said, “Your Majesty is lying uncomfortable.” She replied, “Yes, but well enough to die.” She was gone a few moments later.

The large shared tomb of Maria Theresa and Francis. In front is their son, Joseph II. Photo by Moniek Bloks

The large shared tomb of Maria Theresa and Francis. In front is their son, Joseph II. Photo by Moniek BloksOn 3 December 1780, she was interred next to her husband in the Imperial Crypt. She had reigned for 40 years and was arguably one of Austria’s most successful rulers. She had “ruled Europe by the power of her genius, she… had no equal amongst the sovereigns of this century.”7

The post Maria Theresa of Austria – ‘No equal amongst the sovereigns of this century’ (Part five) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 24, 2021

A royal Christmas wishlist

Get ready for Christmas with this royally inspired Christmas wishlist!

Anne Boleyn’s Moost Happi portrait medal

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe portrait on this medal is the only undisputed contemporary portrait of Anne Boleyn. It has been reconstructed and can now be bought in many forms and metals. What you see above is the pendant in polished silver. As this is 3D-printed on demand, make sure you order it in time! Order here.

Diana Pullover Hoodie

This bright pink hoodie with Diana’s signature on it will keep you warm all winter. You can order it here up to size 2XL.

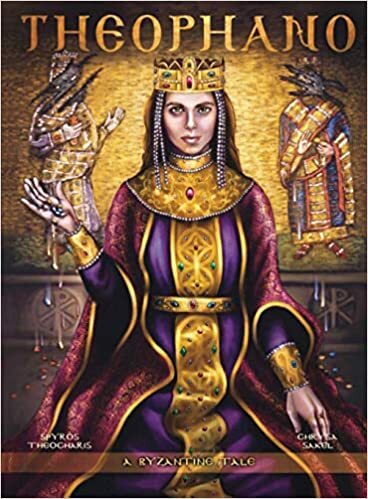

Theophano: A Byzantine tale

Step out of your comfort zone with this historical graphic novel. Order it here (UK) or here (US).

Funko Pop Royals

Photo by Moniek Bloks

Photo by Moniek BloksThe Funko Pop Royals collection consists of several figurines from the British royal family, including a little corgi!

Order them here:

Queen Elizabeth II and Corgi – US & UK

Diana, Princess of Wales (you get either the red one or the black one) – US & UK

The Duke and Duchess of Sussex set – US & UK

The Duchess of Cambridge – US & UK

The Duke of Cambridge – US & UK

Strangely, the Duchess of Cornwall is excluded from this line.

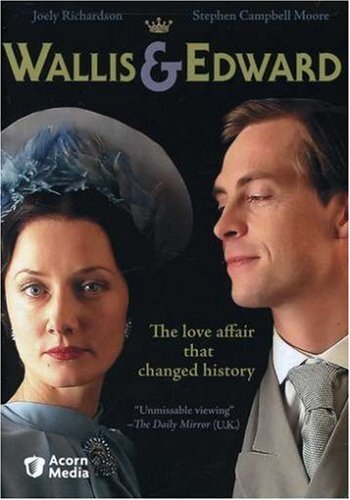

Wallis & Edward

With Joely Richardson as Wallis, the Duchess of Windsor, this is one of my favourite depictions of the Duke and Duchess’s story. It’s available to watch on Prime but can also be bought as a DVD.

Prime – US

DVD – US

History of Royal Women’s books

I could hardly make this list without including my own books. Princess Carolina and her great-great-granddaughter Empress Hermine and her great-great-great-granddaughter Queen Wilhelmina will make an excellent addition to any royal library.

Order them here:

Carolina of Orange-Nassau: Ancestress of the Royal Houses of Europe – US & UK

Hermine: An Empress in Exile: The Untold Story of the Kaiser’s Second Wife – US & UK

Queen Wilhelmina – A collection of articles – US & UK

The post A royal Christmas wishlist appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 23, 2021

Maria Theresa of Austria – ‘Let others wage war: thou, happy Austria, marry’ (Part four)

The death of Francis meant that Maria Theresa had to rebuild her world. In the months following his death, she remained in deep mourning. In her prayer book, she recorded the exact length of his life, to the hour: “Emperor Francis, my husband, lived 56 years, 8 months, 10 days and died on August 18, 1765, at 9.30 P.M. So he lived: months 680, weeks 2,958 1/2, Days 20,778, Hours 496,991. My happy marriage lasted 29 years, 6 months and 6 days.”1

Meanwhile, her son Joseph was becoming antsy. He was ready to take over power, but Maria Theresa wasn’t ready to just hand it all over. The Council of Electors eventually gave her an ultimatum – share the throne with Joseph or abdicate. She conceded, and on 18 November 1765, a co-regency between the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy was declared. The Grand Duchy of Tuscany passed to their second son Leopold, and he and his new wife arrived in Florence in September 1765. Meanwhile, Joseph’s wife, now Empress Maria Josepha, lived a solitary life.

On 8 April 1766, Maria Theresa’s second surviving daughter Maria Christina married Prince Albert of Saxony, and through her dowry, they became Duke and Duchess of Teschen. They were also appointed governors of the Austrian Netherlands. It only added to her grief. Maria Theresa wrote, “My heart has received such a blow which it feels especially on a day such as this. In eight months, I have lost the most adorable husband… and a daughter who after the loss of her father was my chief object, my consolation, my friend.”2 Marrying her children well now became Maria Theresa’s chief goal.

On 14 January 1767, another granddaughter was born “to the great disappointment of this place [Florence] and Vienna.”3 Leopold’s wife Maria Luisa had given birth to a daughter – also named Maria Theresa. The Empress “wanted a grandson to console her under the despair she is in [over her fights with] the Emperor.”4 Even with shared power, Joseph was not happy. A third granddaughter was born on 6 May 1767 – to Maria Christina and Prince Albert. Tragically, the little girl lived for just one day, and Maria Christina would never have any other children.

On 28 May 1767, the long-suffering Empress Maria Josepha died – quite unexpectedly – of smallpox. At the time of her death, Maria Theresa had five marriageable daughters5, but smallpox would throw Maria Theresa’s marriage plans for a spin. Once the beauty of the family, Maria Elisabeth was left disfigured by the disease and so was taken off the marriage market. Maria Theresa, herself, also fell ill but survived. Thus, her third-youngest daughter Maria Josepha was matched with King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies (then just the King of Naples). Days before her departure, Maria Theresa took her daughter to pray at the improperly sealed tomb of Empress Maria Josepha. It is unclear if Maria Josepha was already ill or if she contracted the disease for the late Empress’s body as she fell ill rather quickly after the visit, but whatever the case, the young Archduchess died on 15 October 1767. She was just 16 years old.

Maria Theresa was now down to three marriageable daughters. She left the choice for a new Queen of Naples between Maria Amalia and Maria Carolina to the King. He chose Maria Carolina, and so Maria Amalia was chosen for the Duke of Parma. Neither of the Archduchesses was happy with their chosen husbands. In the midst of all the marriage talk, Maria Theresa finally got a grandson. Maria Luisa gave birth to a son named Francis on 12 February 1768. It would have been Maria Theresa and Francis’s 32nd wedding anniversary, and Maria Theresa was beside herself with joy. She ran into the Hofburg’s imperial theatre, interrupted the play and shouted, “My Poldy’s got a boy!”6 Joseph took a serious interest in his young nephew, who would one day become the Emperor.

Two months later, Maria Carolina married the King of Naples in a proxy ceremony, and she left for Naples that very afternoon. The family gathered in the courtyard at Schönbrunn to bid the young Queen farewell. Maria Carolina jumped out of the carriage at the last second to give her youngest sister Marie Antoinette a final hug.

Tragedy struck once more in early 1769. The young Archduchess Maria Theresa, the only surviving child of Emperor Joseph and his first wife Isabella, fell ill with pleurisy. The 7-year-old archduchess could be heard crying throughout the Hofburg, but she refused all food and water as she became sicker. She died in her father’s arms on 23 January 1769. She was laid to rest next to her mother. Her grief-stricken father asked to keep her writings and her “white dimity dressing-gown embroidered with flowers.”7

That same year, Maria Amalia became Duchess of Parma, despite already being “violently in love” with Prince Charles of Zweibrücken.8 That Maria Theresa forced her daughter to marry the Duke of Parma permanently fractured their relationship. On 1 July 1769, a similar scene took place in the courtyard of Schönbrunn, and Maria Amalia curtseyed deep before her mother. They would never see each other again.

There was now just one daughter to be married off – Marie Antoinette. Her chosen husband would be the Dauphin of France – Louis Auguste. His father, Louis Ferdinand, had died in 1765, and so Louis Auguste was the heir of his grandfather King Louis XV. His mother, too, had died – in 1767. Maria Theresa had long sought a marriage with France, but Marie Antoinette was now her only option left with all the shuffling. It wasn’t until the wedding date was set that Maria Theresa realised how unprepared Maria Antoinette was for the task ahead.

Part five coming soon.

The post Maria Theresa of Austria – ‘Let others wage war: thou, happy Austria, marry’ (Part four) appeared first on History of Royal Women.

November 21, 2021

Giveaway – One set of History of Royal Women’s three books

Fill in the Rafflecopter below to have a chance at winning one of the three available sets of my three books! I will sign them if you like!

a Rafflecopter giveawayThe post Giveaway – One set of History of Royal Women’s three books appeared first on History of Royal Women.

Maria Theresa of Austria – Mother and Empress (Part three)

On 4 February 1750, Maria Theresa gave birth to another daughter, Maria Johanna. But a family tragedy was to come later that year. With her health destroyed by the many “fertility treatments,” Maria Theresa’s mother, Elisabeth Christine, died on 21 December 1750 at the age of 59. Her heart and entrails were taken from her body and placed in Heart Crypt in the Augustinian Church and the Ducal Crypt in the St. Stephen’s Cathedral respectively. Her body was buried in the Imperial Crypt near her husband. With a tenure of just over 29 years, she was the longest-serving Holy Roman Empress consort.

Over the next five years, another five children were born. Maria Josepha was born on 13 August 1752, Ferdinand was born on 1 June 1754, Marie Antoinette was born on 2 November 1755, and finally, Maximilian Francis was born on 8 December 1756. Of her 16 children, ten would survive to adulthood. When her eldest son Joseph was 8 years old, he was given his own establishment and a Jesuit tutor. Field Marshall Charles Batthyány was appointed to turn him into a soldier.

Her daughters also received an education, though it focussed more on feminine pursuits. The schedule stated time for French, penmanship, reading and spelling, Holy Mass, needlework and the rosary in church. She said her daughters “were born to obey.”1 It probably never even occurred to Maria Theresa to prepare her daughters better for the roles they were bound to play – their minds were never challenged.

By 1760, it was time for the first of her children to marry. Joseph was 19 years old, and the chosen bride was Isabella of Parma, a granddaughter of King Louis XV of France and Maria Leszczyńska. Both Maria Theresa and Joseph adored her, but Isabella’s adoration focussed mainly on her sister-in-law Maria Christina. She had fallen head over heels in love with Maria Christina, and her surviving correspondence is proof of that. Isabella soon became trapped with her own conflicting feelings and she became obsessed with death as the only way out of them. Maria Christina largely returned Isabella feelings, though perhaps not so fatalistically. She even reproached Isabella, “Allow me to tell you that your great longing for death is an outright evil thing.”2

Nevertheless, Maria Theresa became a grandmother on 20 March 1762 with the birth of her namesake granddaughter Maria Theresa. Isabella reportedly suffered two miscarriages in quick succession before falling pregnant for a fourth time in early 1763. During the last month of her pregnancy, Isabella became ill with smallpox. On the third day of her illness, she gave birth to a premature girl, whom she named Christina, and who died moments after being born. Although Maria Theresa nursed her “as if she had been her own child,”3 Isabella died on 27 November 1763. She had predicted her own death that summer as the family returned to Vienna from Laxenburg. As the carriage reached a hill overlooking Vienna, she had stated, “Death is waiting for me there.”4 Joseph was devastated by her death.

However, they could not mourn her death for long. Joseph was the future Emperor, and he needed a son and, thus, another wife. In 1765, he was finally convinced to remarry, and the chosen bride was his second cousin, Maria Josepha of Bavaria (the daughter of Maria Amalia of Austria). He did not like her, and after their first meeting, he wrote, “She is twenty-six. She has never had smallpox, and the very thought of the disease makes me shudder. Her figure is short, thick-set, and without a vestige of charm. Her face is covered with spots and pimples. Her teeth are horrible.”5 He never grew to love her and treated her coldly. Even Maria Christina commented that “if I were his wife and so maltreated I would run away and hang myself on a tree in Schönbrunn.”6

Just 7 months after Joseph’s second wedding, Maria Theresa’s husband Francis died quite suddenly. The family was just celebrating the wedding of Joseph’s brother Leopold to Maria Luisa of Spain on 5 August, where the groom himself had also been dangerously ill with pleurisy. Francis had suffered a slight seizure on 17 August, but he felt better the next day. He collapsed as he walked back to the palace after a theatre performance. He was carried into the anteroom, but by then, he was already dead. Maria Theresa soon arrived and knelt silently beside him. She was devastated and had to finally be carried away by force.

Maria Theresa allowed no one in her rooms for the rest of the evening, and it wasn’t until the following morning that she allowed one of her ladies to help her dress. She also ordered her lady to cut her hair short. She then called her family to her, asked them if they were well and sent them away again. She ordered Francis’s shroud to be sewn in her own room, and she would help with the sewing. She prayed and sewed all day. Joseph silently took over the order of the day. Although he had become the new Holy Roman Emperor, his mother was still Queen of Hungary and Bohemia. If he were to have any power – she would need to give it to him. In her grief, she considered giving him all control.

Maria Theresa was kind to Francis’s mistress Princess Auersperg, even lamented with her how much they had both lost. Francis had left the Princess a sum of money, and Maria Theresa duly paid it. Maria Theresa would dress in mourning for the rest of her life, and on New Year’s Day 1766, she wrote, “I hardly know myself now, for I have become like an animal with no true life or reasoning power. I forget everything.”7

Part four coming soon.

The post Maria Theresa of Austria – Mother and Empress (Part three) appeared first on History of Royal Women.