Michelle Nevius's Blog, page 2

November 29, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Edison's Phonograph and "I Want to Hold Your Hand"

On November 29, 1877 -- one hundred and forty-one years ago today -- Thomas Edison first demonstrated the device that he would patent seven months later as the phonograph.

Edison's first crude phonograph used tin foil and doubled as both the recording and playback instrument.

At the demonstration, Edison spoke Sarah Josepha Hale's poem "Mary Had a Little Lamb" into a crude microphone. Flipping the phonograph into playback mode, Edison immediately played back the words he'd just recorded to the assembled audience.

And just like that, the future of entertainment was irrevocably changed.

Realizing that tin wasn't the right medium, Edison soon switched to wax cylinders (as shown in the photo of the inventor, above). Wax cylinders were then replaced by round discs and the modern record player was born.

It's a fun coincidence that November 29 is also the anniversary of the Beatles single "I Want to Hold Your Hand," the song that came out in 1963 and catapulted the group into super-stardom. The single was released in the US in December, launching Beatlemania -- and again changing popular entertainment forever.

* * *

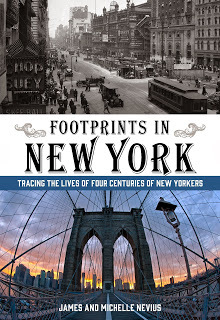

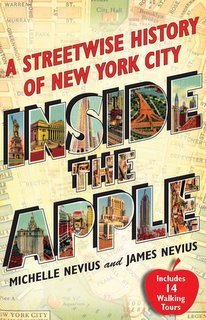

Happy Holidays! If you are looking for a great gifts this holiday season, Inside the Apple and Footprints in New York look great on anyone's shelves!

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on November 29, 2018 08:24

November 22, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Some Thanksgiving Thoughts

The modern holiday of Thanksgiving has become totally enmeshed with the story of the Pilgrims and The Mayflower, though the feast held by those denizens of Plymouth, Massachusetts, was certainly not the first such commemoration in the New World. (Indeed, not only were there early thanksgivings, such as the one at Berkeley Plantation in Virginia in 1619, but often these events were more somber and religious in nature than our current feasts.)

Plymouth RockHowever, the story of the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving is extremely relevant to the history of New York City, because Manhattan was their intended destination.

Plymouth RockHowever, the story of the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving is extremely relevant to the history of New York City, because Manhattan was their intended destination.

As we write in Inside the Apple :

By 1820 — the 200th anniversary of their arrival — the Pilgrims had long been an important part of the cultural DNA of New England, a section of the country that saw itself as separate from (and inherently better than) both the south and the Mid Atlantic states. As an anonymous contributor to the second volume of the New England Quarterly wrote in 1802: “If the inhabitants of New-England are superior to the people of other countries, their superiority is to be attributed to their moral habits.”

In the 1740s, a 94-year-old man named Thomas Faunce had first identified Plymouth Rock as the spot where the Pilgrims had come ashore; on the eve of the Revolution, the boulder was dragged by a team of twenty oxen to Plymouth’s town square to be placed at the foot of a liberty pole. During the move the rock broke in two — a sign of America’s impending war with Britain, some thought — which only served to endow it with greater meaning.

* * *Modern Thanksgiving didn't really get started until after the Civil War. James wrote a history of that holiday for the Guardian in 2016:

* * *Abraham Lincoln actually declared Thanksgiving Day twice.

In the words of the original proclamation, issued in October 1863 and actually written by Secretary of State William Seward, the former senator from and governor of New York:

In the words of the original proclamation, issued in October 1863 and actually written by Secretary of State William Seward, the former senator from and governor of New York:

The first Thanksgiving of 1863, August 6, was celebrated with proper solemnity. As the New York Times noted the next day, "The National Thanksgiving was observed throughout the City yesterday by an almost entire abstaining from secular pursuits. The stores throughout were closed, and there appeared to be a very general desire to unite in the purposes of the day -- Thanksgiving and Praise. Very many of the churches were open, where proper observances were had, and each was crowded to overflowing." What they were praising and/or hoping for was continued Union success; with the Union victory at Gettysburg in July, many hoped that tide of the war had finally turned in favor of the North.

Of course, on the minds of New Yorkers would have been the fighting closer to home -- the Civil War draft riots -- which had waged on the streets less than a month earlier. However, it is unclear if the riots played any role in the Thanksgiving commemorations.

Having celebrated Thanksgiving in August, why did Lincoln then proclaim another one in November? The declaration for this second Thanksgiving seems little different from the first; there had been no major Union victories in the meantime for which the nation could express thanks; and Lincoln's proclamation doesn't make any ties to harvest festivals, the Pilgrims, or any of the things we now firmly associate with the holiday.

* * *Happy Thanksgiving! If you are looking for a great gifts this holiday season, Inside the Apple and Footprints in New York look great on anyone's shelves!

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Plymouth RockHowever, the story of the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving is extremely relevant to the history of New York City, because Manhattan was their intended destination.

Plymouth RockHowever, the story of the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving is extremely relevant to the history of New York City, because Manhattan was their intended destination.As we write in Inside the Apple :

The Pilgrims’ voyage to the New World, which started out from the Dutch city of Leiden where they’d lived in exile, worried the fur traders. In the common Thanksgiving story, it’s usually left out that the Pilgrims weren’t en route to Massachusetts at all (which lay outside English territory) but instead had been granted the island at the northern limit of the Virginia colony: Manhattan. (Virginia’s claim to Manhattan was long-standing. When John Smith wrote to Henry Hudson about a Northwest Passage, it was because the river he was describing was part of Virginia.)

After a rocky start, where the Pilgrims were forced to abandon one of their two ships—perhaps because of sabotage by Dutch merchants—they continued on to the New World on the Mayflower, disembarking in Plymouth after a half-hearted attempt to sail further south. When it became clear that the English settlers were not going to move to Manhattan, Dutch traders hurriedly began staking a firmer claim to their territory.

By 1820 — the 200th anniversary of their arrival — the Pilgrims had long been an important part of the cultural DNA of New England, a section of the country that saw itself as separate from (and inherently better than) both the south and the Mid Atlantic states. As an anonymous contributor to the second volume of the New England Quarterly wrote in 1802: “If the inhabitants of New-England are superior to the people of other countries, their superiority is to be attributed to their moral habits.”

In the 1740s, a 94-year-old man named Thomas Faunce had first identified Plymouth Rock as the spot where the Pilgrims had come ashore; on the eve of the Revolution, the boulder was dragged by a team of twenty oxen to Plymouth’s town square to be placed at the foot of a liberty pole. During the move the rock broke in two — a sign of America’s impending war with Britain, some thought — which only served to endow it with greater meaning.

* * *Modern Thanksgiving didn't really get started until after the Civil War. James wrote a history of that holiday for the Guardian in 2016:

Sarah HaleWe owe our modern holiday to a writer named Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor, novelist and poet (she penned “Mary Had a Little Lamb”).... In her first novel, 1827’s Northwood, Hale devoted multiple chapters to Thanksgiving; at one point, the character Squire opines that Thanksgiving will eventually be celebrated “on the same day, throughout all the states and territories” and “will be a grand spectacle of moral power and human happiness, such as the world has never yet witnessed."

[Hale] took over Godey’s Lady’s Book, which she grew into America’s most popular periodical. Though she insisted that Godey’s remain apolitical, each year Hale would advocate in the magazine’s pages for a New England-style Thanksgiving holiday to be “celebrated throughout the whole country on the same day”. She also wrote to every state governor each year asking that a Thursday in November (sometimes the third, often the last) be dedicated to Thanksgiving.

Many southern politicians were less than enthused. Governor Henry Wise of Virginia wrote back in 1856 that the “theatrical national claptrap of Thanksgiving” was merely a mask to aid “other causes”. By other causes, Wise meant abolition. He knew Thanksgiving was a Trojan horse; cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie would get the northerners through the front door, and they’d soon be spreading their “claptrap” throughout the slaveholding south.

That same year, the Evening Star in Washington DC, along with other southern newspapers, complained that Thanksgiving was an attempt to replace the “legitimate Christian holiday” of Christmas with a secular day where “an astonishing quantity of execrable liquor will be guzzled”.

Still, by 1863, Hale had convinced Abraham Lincoln to declare a Day of National Thanksgiving, though it would not become a true national holiday until Franklin D Roosevelt signed it into law in 1941.

* * *Abraham Lincoln actually declared Thanksgiving Day twice.

In the words of the original proclamation, issued in October 1863 and actually written by Secretary of State William Seward, the former senator from and governor of New York:

In the words of the original proclamation, issued in October 1863 and actually written by Secretary of State William Seward, the former senator from and governor of New York:I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.However, this was actually Lincoln's second Thanksgiving proclamation of the year. On July 16, he had issued the following proclamation (again, likely by Seward):

Now, therefore, be it known that I do set apart Thursday, the sixth day of August next, to be observed as a day for National Thanksgiving, praise and prayer, and I invite the people of the United States to assemble on that occasion in their customary places of worship, and in the form approved by their own conscience, render the homage due to the Divine Majesty for the wonderful things He has done in the Nation's behalf, and invoke the influence of His Holy Spirit, to subdue the anger which has produced, and so long sustained a needless and cruel rebellion; to change the hearts of the insurgents; to guide the counsels of the Government with wisdom adequate to so great a National emergency, and to visit with tender care, and consolation throughout the length and breadth of our land, all those who, through the vicissitudes of marches, voyages, battles and sieges, have been brought to suffer in mind, body or estate, and finally to lead the whole nation through paths of repentance and submission to the Divine will, back to the perfect enjoyment of union and fraternal peace.(FYI: That's one sentence.)

The first Thanksgiving of 1863, August 6, was celebrated with proper solemnity. As the New York Times noted the next day, "The National Thanksgiving was observed throughout the City yesterday by an almost entire abstaining from secular pursuits. The stores throughout were closed, and there appeared to be a very general desire to unite in the purposes of the day -- Thanksgiving and Praise. Very many of the churches were open, where proper observances were had, and each was crowded to overflowing." What they were praising and/or hoping for was continued Union success; with the Union victory at Gettysburg in July, many hoped that tide of the war had finally turned in favor of the North.

Of course, on the minds of New Yorkers would have been the fighting closer to home -- the Civil War draft riots -- which had waged on the streets less than a month earlier. However, it is unclear if the riots played any role in the Thanksgiving commemorations.

Having celebrated Thanksgiving in August, why did Lincoln then proclaim another one in November? The declaration for this second Thanksgiving seems little different from the first; there had been no major Union victories in the meantime for which the nation could express thanks; and Lincoln's proclamation doesn't make any ties to harvest festivals, the Pilgrims, or any of the things we now firmly associate with the holiday.

* * *Happy Thanksgiving! If you are looking for a great gifts this holiday season, Inside the Apple and Footprints in New York look great on anyone's shelves!

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on November 22, 2018 09:16

October 25, 2018

Postcard Thursday: The Erie Canal

I've got an old mule and her name is Sal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

She's a good old worker and a good old pal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

We've hauled some barges in our day

Filled with lumber, coal, and hay

And every inch of the way we know

From Albany to Buffalo

-- From "Low Bridge Everybody Down" aka "Erie Canal"

from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

On October 26, 1825, one of the most important engineering feats of the 19th century was completed with the opening of the Erie Canal. A cannon was fired in Buffalo to mark the moment. Then, a series of cannons along the canal and the Hudson River had been set up for the occasion and as each gunner heard the shot, he fired his own; in 90 minutes the news passed, cannon to cannon, along the waterway to New York City.

Ten days later, New York's governor, DeWitt Clinton, stood on the deck of a packet boat anchored off Sandy Hook and poured a barrel of water from Lake Erie into the Atlantic Ocean. This "wedding of the waters," as it came to be known, was the symbolic completion of the Erie Canal, the most important waterway of its day and the engineering project that once and for all sealed New York's fate as the most important commercial city in America.

An entire chapter of Footprints in New York is dedicated to Governor (and NYC mayor) Clinton, the unsung hero of 19th-century New York politics. As we write in the book, Clinton

Prior to the canal's opening, it was cheaper to bring goods from Liverpool to New York than to haul them overland from Illinois. Once the canal was finished, not only did New York have access to plentiful raw materials from the Midwest, finished products could now also speed to the heartland, opening up new markets for the city's burgeoning manufacturing base. By the time of the Civil War, New York's control over shipping was so complete that nearly all the cotton being shipped from the south to Europe was being sent out of New York harbor rather than directly from southern ports.

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

She's a good old worker and a good old pal

Fifteen years on the Erie Canal

We've hauled some barges in our day

Filled with lumber, coal, and hay

And every inch of the way we know

From Albany to Buffalo

-- From "Low Bridge Everybody Down" aka "Erie Canal"

from the collection of the New-York Historical Society

from the collection of the New-York Historical SocietyOn October 26, 1825, one of the most important engineering feats of the 19th century was completed with the opening of the Erie Canal. A cannon was fired in Buffalo to mark the moment. Then, a series of cannons along the canal and the Hudson River had been set up for the occasion and as each gunner heard the shot, he fired his own; in 90 minutes the news passed, cannon to cannon, along the waterway to New York City.

Ten days later, New York's governor, DeWitt Clinton, stood on the deck of a packet boat anchored off Sandy Hook and poured a barrel of water from Lake Erie into the Atlantic Ocean. This "wedding of the waters," as it came to be known, was the symbolic completion of the Erie Canal, the most important waterway of its day and the engineering project that once and for all sealed New York's fate as the most important commercial city in America.

An entire chapter of Footprints in New York is dedicated to Governor (and NYC mayor) Clinton, the unsung hero of 19th-century New York politics. As we write in the book, Clinton

was the most important politician of his generation—perhaps the most important politician New York has ever had—which, considering the company, is quite an achievement.

Clinton was New York’s junior senator; then, he served ten one-year terms as the city’s mayor between 1803 and 1815. Later, as governor, he oversaw the building of the Erie Canal, the biggest engineering project of its day, which radically transformed New York’s economy. Had Clinton carried the state of Pennsylvania in the election of 1812—which he nearly did—he would have been president of the United States, and might have brought a quick resolution to the war with Great Britain.

Clinton’s influence is incalculable. From expanding trade through the Erie Canal to overseeing the real estate revolution embodied in the city’s rigid grid plan, the effects of Clinton’s years in politics are still felt today by every New Yorker.

On November 4, 1825, in a ceremony for dignitaries and the press, Governor Clinton poured a small cask of water into the Atlantic Ocean. An artist captured the moment: Clinton stands on the edge of a barge, the miniature cask grasped in his hands, as the water—collected ten days earlier in Lake Erie—gracefully cascades into the sea.

Prior to the canal's opening, it was cheaper to bring goods from Liverpool to New York than to haul them overland from Illinois. Once the canal was finished, not only did New York have access to plentiful raw materials from the Midwest, finished products could now also speed to the heartland, opening up new markets for the city's burgeoning manufacturing base. By the time of the Civil War, New York's control over shipping was so complete that nearly all the cotton being shipped from the south to Europe was being sent out of New York harbor rather than directly from southern ports.

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on October 25, 2018 08:41

October 18, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Melville's Whale

site for processing whale oil, AntarcticaOn October 18, 1851, a novel called The Whale by Herman Melville was published in England. It would come out in America about a month later under the title Moby Dick and would become a landmark of 19th-century American literature. (Though not immediately -- the first edition was a failure.)

site for processing whale oil, AntarcticaOn October 18, 1851, a novel called The Whale by Herman Melville was published in England. It would come out in America about a month later under the title Moby Dick and would become a landmark of 19th-century American literature. (Though not immediately -- the first edition was a failure.)Melville was born in Lower Manhattan and -- when he wasn't working on square-rigged sailing ships -- spent most of his life in the city.

"There now is your insular city of the Manhattoes, belted round by wharves as Indian isles by coral reefs—commerce surrounds it with her surf. Right and left, the streets take you waterward…. Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip, and from thence, by Whitehall, northward. What do you see?—Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries."

-- Herman Melville, Moby Dick

For years, there was a bust of Melville inset into the wall behind 17 State Street, a 1988 office tower built by Emory Roth & Sons in the Financial District. The bust marked the spot (sort of) where Melville was born at 6 Pearl Street.

However, a recent renovation of the plaza has erased the Melville memorial. Do any readers know what happened to the bust? We've reached out to the leasing agent for the building, but so far have not heard back.

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on October 18, 2018 09:47

October 11, 2018

Postcard Thursday: The DAR

On October 11, 1890, the Daughters of the American Revolution was founded. The organization was created as part of a wave of patriotic sentiment that gripped America after the Civil War. It was also, quite frankly, a way for white, native-born women to remind immigrants that America had literally been created by the ancestors of the DAR.

James walked around Lower Manhattan this year looking for plaques and markers that the DAR (and other, similar organizations) had placed around the Financial District to remind people of the area's Revolutionary history. You can read that story in Curbed at

https://ny.curbed.com/2018/3/28/17168160/new-york-city-walking-tour-historic-guidebooks-1909.

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on October 11, 2018 07:57

September 27, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Wall Street

For nearly four centuries, the lower tip of Manhattan has been defined by Wall Street, the path of which was originally marked by a nine-foot-high wooden palisade.

James digs deep into the the street's history for Curbed NY in his most recent feature story, which you can read here: https://ny.curbed.com/2018/9/26/17900962/wall-street-new-york-city-history.

* * *

REMINDER: On Sunday, October 7, at 11:00AM, we will be guiding a tour of Gilded-Age New York. All the details are at http://blog.insidetheapple.net/2018/0.... There are only a few spots left at just $15 a piece -- book now!

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on September 27, 2018 08:46

September 12, 2018

Postcard Thursday: The Death of General Wolfe

The Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West.

The Death of General Wolfe by Benjamin West.On September 13, 1759, Major-General James Wolfe died during the Siege of Quebec in the French and Indian War (aka the Seven Years War). Wolfe's heroic victory won the war for Britain, allowing it to seize most of Atlantic Canada, and made Wolfe both a martyr to the cause and an instant celebrity.

The most famous commemoration of Wolfe's death on the Plains of Abraham is Benjamin West's painting (above), now in the National Gallery of Canada. But New York had its own memorial to General Wolfe, an obelisk that was erected in Greenwich Village at the end of what came to be known as "Obelisk Lane" or "Monument Lane."

The General Wolfe monument at Stowe.

The General Wolfe monument at Stowe.Very little is known about the memorial. Some think that it was based on a similar obelisk erected in Stowe in Buckinghamshire, England, by Lord Temple, which still stands today. But this is just speculation. Indeed, if it weren't for a few old memoirs and a couple of maps, we wouldn't know that the monument existed at all.

Montressor Map, ca. 1765-1766.

Montressor Map, ca. 1765-1766.The obelisk was likely erected soon after Wolfe's death, probably in 1762 by Robert Monckton. Monckton was Wolfe's second in command at Quebec and in 1762 he became royal governor of the Province of New York. He lived in Greenwich Village, in a house owned by Admiral Peter Warren, which stood only a few minutes walk from the monument.

The obelisk appears on the Montressor map of 1765-66, where a "Road to the Obelisk" leads to a spot just east of Oliver De Lancey's farm marked "Obelisk Erected to the Memory of General Wolf [sic] and Others."

The Ratzer Plan, ca. 1766-77The Ratzer Plan of the city -- issued in 1766 or 1777 -- shows a similar road, calling it "The Monument Lane." If you are familiar with this part of Greenwich VIllage, that lane is now Greenwich Avenue, which runs northwest from Sixth Avenue just south of Christopher Streets. However, many other small streets in the Village were once considered part of the lane. As the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society wrote in their annual report of 1914:

The Ratzer Plan, ca. 1766-77The Ratzer Plan of the city -- issued in 1766 or 1777 -- shows a similar road, calling it "The Monument Lane." If you are familiar with this part of Greenwich VIllage, that lane is now Greenwich Avenue, which runs northwest from Sixth Avenue just south of Christopher Streets. However, many other small streets in the Village were once considered part of the lane. As the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society wrote in their annual report of 1914:Monument Lane began at the present Fourth Avenue and Astor Place and ran westward along the present Astor Place; thence to Washington Square North about 100 feet west of Fifth Avenue, where it crossed a brook called at various times Minetta Brook, Bestevaer's Kill, etc.; thence to the present Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Lane; thence along the present Greenwich Lane to Eighth Avenue between Thirteenth and Fourteenth Streets, where it intersected the now obsolete Southampton Road; thence northward about 150 or 200 feet farther, where it terminated at the Monument.Tracing those roads today, it seems likely that the road probably incorporated what today is Washington Mews and MacDougal Alley, just north of Washington Square, roads that have long been thought to be Native American trails. Indeed, it would not be at all surprising to discover that all of Monument Lane existed long before Europeans settled the area that would come to be known as Greenwich Village.

No one is entirely sure when the monument to General Wolfe was taken down and by whom, but by the time the next map of Manhattan was drawn, ca. 1773, the monument is gone and references to Monument Lane disappear soon thereafter. Some speculate that Oliver De Lancey, a loyalist, destroyed the monument when his lands were confiscated by the Americans after the war, but it seems more likely that the obelisk was already long gone by that time.

(This post was adapted and updated from an earlier blog entry.)

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on September 12, 2018 09:13

August 23, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Trinity's Real Estate Holdings

looking up Wall Street at Trinity Church

looking up Wall Street at Trinity ChurchYesterday, James had a feature in Curbed NY about the history of Trinity Church's real estate holdings in Lower Manhattan. By the end of the nineteenth century, Trinity had become the second-largest land owners in New York City, but much of what they owned in the area now know as Tribeca was actually in terrible shape. Trinity was called out by the local press as one of the city's biggest slumlords and it became a huge scandal.

(This area has been in the news recently because Disney is going to be building a new headquarters on some of Trinity's land in what was once the center of this slum.)

The whole story is fascinating:https://ny.curbed.com/2018/8/22/17764064/trinity-church-real-estate-history-hudson-square.

an artist's rendition of what the original Trinity looked like ca. 1698

an artist's rendition of what the original Trinity looked like ca. 1698* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on August 23, 2018 07:35

August 9, 2018

Postcard Thursday: An Assassination Attempt Caught on Camera

On August 9, 1910, the mayor of New York, William Jay Gaynor, posed for photos on the deck on the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. He was about to embark on a vacation to Europe, and as he stood on deck he was approached by J.J. Gallagher, a former municipal dock worker who had been fired about a month earlier. Gallagher shot the mayor at close range--just as New York World photographer William Warnecke snapped the picture above. Gallagher was immediately subdued. When asked why he'd done it, Gallagher said simply: "He took away my bread and meat. I had to do it."

Mayor Gaynor, a native of the village of Oriskany in Oneida County, was best known as a jurist, having been appointed to State's Supreme Court in 1893 and the Appellate Division in 1905. Tammany Hall Democrats, disappointed by their two-term standard bearer, George B. "Max" McClellan, picked Gaynor to run in 1909. Gaynor handily defeated the Republic/Fusion candidate, Otto T. Bannard, in part because Republican votes were siphoned off by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst who ran as an independent.

Instead of appointing Tammany Hall cronies to fill vacancies at City Hall, however, Gaynor instituted broad-reaching civil service reforms and was a champion of extending the new IRT subway.

Though the bullet lodged in Mayor Gaynor's throat, he made a relatively speedy recovery. (Gallagher, meanwhile, was tried, found insane, and sent to an asylum in Trenton, New Jersey.)

In 1913, Gaynor received the backing of a reform coalition to run for a second term as mayor. (Tammany Hall wanted nothing more to do with him.) On September 3, he left for Europe on the SS Baltic and six days later, he died in a deck chair of a heart attack; it is unclear whether or not Gallagher's assassination attempt had weakened the mayor and contributed to his death. Gallagher was never tried with murder--he had died at the Trenton asylum a few months earlier.

Very few New York City mayors are honored in our parks, but if you happen to be in Brooklyn Heights, head to Cadman Plaza where you'll find the handsome Gaynor Memorial by Adolph Weinman. (Weinman is best known in New York for his statue Civic Fame which stands atop the Municipal Building on Centre Street.)

Very few New York City mayors are honored in our parks, but if you happen to be in Brooklyn Heights, head to Cadman Plaza where you'll find the handsome Gaynor Memorial by Adolph Weinman. (Weinman is best known in New York for his statue Civic Fame which stands atop the Municipal Building on Centre Street.)* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on August 09, 2018 10:33

July 26, 2018

Postcard Thursday: Poe's Lost Home

There's a story in the newly revamped Gothamist/WNYC today about the efforts to have Walt Whitman's sole remaining New York City home landmarked.

(You can read it at http://gothamist.com/2018/07/26/walt_whitman_brooklyn_home.php)

This brings to mind the similar efforts to save Edgar Allan Poe's only Manhattan home, a townhouse at 85 Amity Street (today's West 3rd Street) in Greenwich Village. Today that same block houses the Poe Study Center, but that building isn't Poe's original home.

As we write in Footprints in New York:

85 Amity Street (left) and the Poe Study Center (right); courtesy of the New York Preservation Archive Project

85 Amity Street (left) and the Poe Study Center (right); courtesy of the New York Preservation Archive Project

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

(You can read it at http://gothamist.com/2018/07/26/walt_whitman_brooklyn_home.php)

This brings to mind the similar efforts to save Edgar Allan Poe's only Manhattan home, a townhouse at 85 Amity Street (today's West 3rd Street) in Greenwich Village. Today that same block houses the Poe Study Center, but that building isn't Poe's original home.

As we write in Footprints in New York:

The Poes lived nine places in the city, seven of them in just a two-year period.... Having published “The Raven” in the New York Evening Mirror in January 1845, Poe set to work at 85 Amity Street revising the poem for The Raven and Other Poems, published that November. He also began his series “Literati of New York City” while residing at 85 Amity, and may have written the bulk of “The Cask of Amontillado” at the boardinghouse too.

By the dawn of the twenty-first century this was the only Poe home in Manhattan still standing. With that in mind, it’s logical to assume it would have merited at least some consideration by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. But in 2000, the commission declined to even hold a hearing. On one hand, this seemed ironic—back in 1969, when creating the Greenwich Village Historic District, the commissioners cited Poe as one of the literary figures whose residence made the neighborhood historically important. Yet, at that time, they had not extended the landmark district’s boundaries the one block necessary to include the Poe house. Three decades later, the commission was not going to raise NYU’s considerably powerful ire by revisiting that decision. Not everyone agreed that the house was worth saving. Kenneth Silverman, a Poe scholar employed by NYU, pointed out that the building had been so significantly altered since 1845 that Poe wouldn’t even recognize it as his own home. He had a point: The stoop had been removed, and the lower floors turned into commercial space. Arched window frames replaced the Greek Revival originals; an incongruous tiled awning jutted out between the second and third stories.

85 Amity Street (left) and the Poe Study Center (right); courtesy of the New York Preservation Archive Project

85 Amity Street (left) and the Poe Study Center (right); courtesy of the New York Preservation Archive Project

What’s more maddening than the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s decision—or, more accurately, their abdication from making a decision—is what NYU did next. In an eleventh-hour move to placate the community, they agreed to rebuild the facade of Poe’s house as part of the new building, install the home’s staircase inside, and provide a room for Poe readings and events. No one was ecstatic about this, but it was better than nothing.

Instead, what people got was worse than nothing. The scaffolding came down...in October 2003 to reveal an ersatz Poe home. Nothing had been preserved; nothing had been rebuilt. It wasn’t even in the right spot.

“Unfortunately, there was not enough of the original bricks to use on the full facade,” an NYU associate dean told the New York Times. “What we did instead was save a portion of them, and put a panel inside the room of the original bricks.”If what happened to Poe house happens to Walt Whitman's Brooklyn home, we may find in the future that the original structure has been torn down and some simulacrum put in its place to note the historic importance of the spot. Is this sort of commemoration useful or necessary? That's a deeper question that preservationists and historians have been grappling with for centuries.

* * *

Want to hear more about NYC history?Inside the Apple has recently been released for the first time as an audio book!Visit Amazon or Audible to download today

Footprints in New York: Tracing the Lives of Four Centuries of New Yorkers

Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City

Published on July 26, 2018 09:46