Seth Godin's Blog, page 69

October 6, 2017

If you can't see it, how can you make it better?

It doesn't pay to say to the CFO: These numbers on the P&L aren't true.

And arguing with Walmart or Target about your market share stats doesn't work either.

You can't make things better if you can't agree on the data.

Real breakthroughs are sometimes accompanied by new data, by new metrics, by new ways of measurement. But unless we agree in advance on what's happening, it's difficult to accomplish much.

If you don't like what's happening, an easy way out appears to be to blame the messenger. After all, if the data (whether it's an event, a result or a law of physics) isn't true, you're off the hook.

The argument is pretty easy to make: if the data has ever been wrong before, if there's ever been bias, or a mistake, or a theory that's been improved, well, then, who's to say that it's right this time?

"Throw it all out." That's the cowardly and selfish thing to do. Don't believe anything that makes you look bad. All video is suspect, as is anything that is reported, journaled or computed.

The problem is becoming more and more clear: once we begin to doubt the messenger, we stop having a clear way to see reality. The conspiracy theories begin to multiply. If everyone is entitled to their own facts and their own narrative, then what exists other than direct emotional experience?

And if all we've got is direct emotional experience, our particular statement of reality, how can we possibly make things better?

If we don't know what's happened, if we don't know what's happening, and worst of all, if we can't figure out what's likely to happen next, how do take action?

No successful organization works this way. It's impossible to imagine a well-functioning team of people where there's a fundamental disagreement about the data.

Demand that those you trust and those you work with accept the ref's calls, the validity of the x-ray and the reality of what's actually happening. Anything less than that is a shortcut to chaos.

October 5, 2017

Defining authenticity

For me, it's not "do what you feel like doing," because that's unlikely to be useful.

You might feel like hanging out on the beach, telling off your boss or generally making nothing much of value. Authenticity as an impulse is hardly something to aspire to.

It's not, "say whatever is on your mind," either.

Instead, I define it as, "consistent emotional labor."

We call a brand or a person authentic when they're consistent, when they act the same way whether or not someone is looking. Someone is authentic when their actions are in alignment with what they promise.

Showing up as a pro.

Keeping promises.

Even when you don't feel like it.

Especially when you don't.

October 4, 2017

The pre-steal panic, and why it doesn't matter

When I started as a book packager, there were 40,000 books published every year. Every single book I did, every single one, had a substitute.

Every time we had an idea, every time we were about to submit a proposal, we discovered that there was already a book on that topic. Someone else had 'stolen' my idea before I had even had it.

The only topics I invented that had never been published before were books I was unable to sell.

No one expects you to do something so original, so unique, so off the wall that it has never been conceived of before. In fact, if you do that, it's unlikely you will find the support you need to do much of anything with your idea.

Your ideas have all been stolen already.

So, now you can work to merely make things that are remarkable, delightful and important. You can focus on connection, on making a difference, on building whole solutions that matter.

Isn't that a relief?

October 3, 2017

Change is a word...

for a journey with stress.

You get the journey and you get the stress. At the end, you're a different person. But both elements are part of the deal.

There are plenty of journeys that are stress-free. They take you where you expect, with little in the way of surprise or disappointment. You can call that a commute or even a familiar TV show in reruns.

And there's plenty of stress that's journey-free. What a waste.

We can grow beyond that, achieve more than that and contribute along the way. But to do so, we might need to welcome the stress and the journey too.

October 2, 2017

"You're doing it wrong"

But at least you're doing it.

Once you're doing it, you have a chance to do it better.

Waiting for perfect means not starting.

October 1, 2017

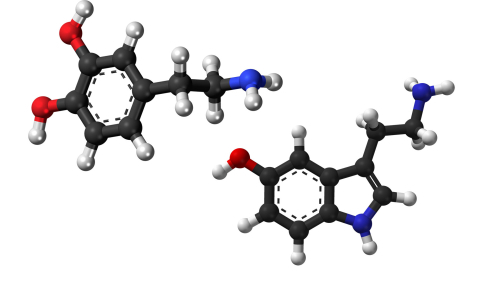

The pleasure/happiness gap

Pleasure is short-term, addictive and selfish. It's taken, not given. It works on dopamine.

Happiness is long-term, additive and generous. It's giving, not taking. It works on serotonin.

This is not merely simple semantics. It's a fundamental difference in our brain wiring. Pleasure and happiness feel like they are substitutes for each other, different ways of getting the same thing. But they're not. Instead, they are things that are possible to get confused about in the short run, but in the long run, they couldn't be more different.

Both are cultural constructs. Both respond not only to direct, physical inputs (chemicals, illness) but more and more, to cultural ones, to the noise of comparisons and narratives.

Marketers usually sell pleasure. That's a shortcut to easy, repeated revenue. Getting someone hooked on the hit that comes from caffeine, tobacco, video or sugar is a business model. Lately, social media is using dopamine hits around fear and anger and short-term connection to build a new sort of addiction.

On the other hand, happiness is something that's difficult to purchase. It requires more patience, more planning and more confidence. It's possible to find happiness in the unhurried child's view of the world, but we're more likely to find it with a mature, mindful series of choices, most of which have to do with seeking out connection and generosity and avoiding the short-term dopamine hits of marketed pleasure.

More than ever before, we control our brains by controlling what we put into them. Choosing the media, the interactions, the stories and the substances we ingest changes what we experience. These inputs lead us to have a narrative, one that's supported by our craving for dopamine and the stories we tell ourselves. How could it be any other way?

Scratching an itch is a route to pleasure. Learning to productively live with an itch is part of happiness.

Perhaps we can do some hard work and choose happiness.

[HT to the first few minutes of this interview.]

September 30, 2017

Looking for a friend (or a fight)

If you gear up, put yourself on high alert and draw a line in the sand, it's likely you'll find the enemy you seek.

On the other hand, expecting that the next person you meet will be as open to possibility as you are might just make it happen.

September 29, 2017

Facing the inner critic

Part of his power comes from the shadows.

We hear his voice, we know it by heart. He announces his presence with a rumble and he runs away with a wisp of smoke.

But again and again, we resist looking him in the eye, fearful of how powerful he is. We're afraid that like the gorgon, he will turn us to stone. (I'm using the male pronoun, but the critic is a she just as often).

He's living right next to our soft spot, the (very) sore place where we store our shame, our insufficiency, our fraudulent nature. And he knows all about it, and pokes us there again and again.

As Steve Chapman points out in his generous TEDx talk, it doesn't have to be this way. We can use the critic as a compass, as a way to know if we're headed in the right direction.

Pema Chödrön tells the story of inviting the critic to sit for tea. To welcome him instead of running.

It's not comfortable, but is there any other way? The sore spot is unprotectable. The critic only disappears when we cease to matter. They go together.

We can dance with him, talk with him, welcome him along for a long, boring car ride. Suddenly, he's not so dangerous. Sort of banal, actually.

There is no battle to win, because there is no battle. The critic isn't nearly as powerful as you are, not if you are willing to look him in the eye.

September 28, 2017

The crisp meeting

A $30,000 software package is actually $3,000 worth of software plus $27,000 worth of meetings.

And most clients are bad at meetings. As a result, so are many video developers, freelance writers, conference organizers, architects and lawyers.

If you're a provider, the analysis is simple: How much faster, easier and better-constructed would your work be if you began the work with all the meetings already done, with the spec confirmed, with the parameters clear?

Well, if that's what you need, build it on purpose.

The biggest difference between great work and pretty-good work are the meetings that accompanied it.

The crisp meeting is one of a series. It's driven by purpose and intent. It's guided by questions:

Who should be in the room?

What's the advance preparation we ought to engage in? (at least an hour for every meeting that's worth holding).

What's the budget?

What's the deadline?

What does the reporting cycle look like--dates and content and responsibilities?

Who is the decision maker on each element of the work?

What's the model--what does a successful solution look like?

Who can say no, who can change the spec, who can adjust the budget?

When things go wrong, what's our approach to fixing them?

What constitutes an emergency, and what is the cost (in time, effort and quality) of stopping work on the project to deal with the emergency instead?

Is everyone in the room enrolled in the same project, or is part of the project to persuade the nay-sayers?

If it's not going to be a crisp meeting, the professional is well-advised to not even attend.

It's a disappointing waste of time, resources and talent to spend money to work on a problem that actually should be a conversation first.

September 27, 2017

The under (and the over) achiever

It doesn't matter what the speed limit is. He's going to drive five miles slower.

And it doesn't matter to the guy in the next car either... he's going to drive seven miles faster.

It's not absolute, it's relative.

The person wearing the underachiever hat (it's temporary and he's a volunteer) will get a C+ no matter how difficult the course is. And the person who measures himself against the prevailing standard will find a way to get an A+, even if he has to wheedle or cut corners to get it.

When leading a team, it's tempting to slow things down for the people near the back of the pack. It doesn't matter, though. They'll just slow down more. They like it back there. In fact, if your goal is to get the tribe somewhere, it pays to speed up, not slow down. They'll catch up.

Seth Godin's Blog

- Seth Godin's profile

- 6535 followers