Seth Godin's Blog, page 253

March 23, 2011

Are you making something?

Making something is work. Let's define work, for a moment, as something you create that has a lasting value in the market.

Twenty years ago, my friend Jill discovered Tetris. Unfortunately, she was working on her Ph.D. thesis at the time. On any given day the attention she spent on the game felt right to her. It was a choice, and she made it. It was more fun to move blocks than it was to write her thesis. Day by day this adds up... she wasted so much time that she had to stay in school and pay for another six months to finish her doctorate.

Two weeks ago, I took a five-hour plane ride. That's enough time for me to get a huge amount of productive writing done. Instead, I turned on the wifi connection and accomplished precisely no new measurable work between New York and Los Angeles.

More and more, we're finding it easy to get engaged with activities that feel like work, but aren't. I can appear just as engaged (and probably enjoy some of the same endorphins) when I beat someone in Words With Friends as I do when I'm writing the chapter for a new book. The challenge is that the pleasure from winning a game fades fast, but writing a book contributes to readers (and to me) for years to come.

One reason for this confusion is that we're often using precisely the same device to do our work as we are to distract ourselves from our work. The distractions come along with the productivity. The boss (and even our honest selves) would probably freak out if we took hours of ping pong breaks while at the office, but spending the same amount of time engaged with others online is easier to rationalize. Hence this proposal:

The two-device solution

Simple but bold: Only use your computer for work. Real work. The work of making something.

Have a second device, perhaps an iPad, and use it for games, web commenting, online shopping, networking... anything that doesn't directly create valued output (no need to have an argument here about which is which, which is work and which is not... draw a line, any line, and separate the two of them. If you don't like the results from that line, draw a new line).

Now, when you pick up the iPad, you can say to yourself, "break time." And if you find yourself taking a lot of that break time, you've just learned something important.

Go, make something. We need it!

March 22, 2011

The triumph of coal marketing

Do you have an opinion about nuclear power? About the relative safety of one form of power over another? How did you come to this opinion?

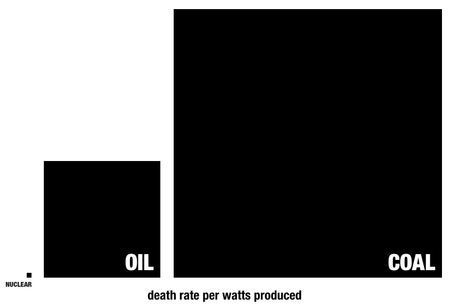

Here are the stats, and here's the image. A non-exaggerated but simple version of his data:

For every person killed by nuclear power generation, 4,000 die due to coal, adjusted for the same amount of power produced... You might very well have excellent reasons to argue for one form over another. Not the point of this post. The question is: did you know about this chart? How does it resonate with you?

Vivid is not the same as true. It's far easier to amplify sudden and horrible outcomes than it is to talk about the slow, grinding reality of day to day strife. That's just human nature. Not included in this chart are deaths due to global political instability involving oil fields, deaths from coastal flooding and deaths due to environmental impacts yet unmeasured, all of which skew it even more if you think about it.

This chart unsettles a lot of people, because there must be something wrong with it. Further proof of how easy it is to fear the unknown and accept what we've got.

I think that any time reality doesn't match your expectations, it means that marketing was involved. Perhaps it was advertising, or perhaps deliberate story telling by an industry. Or perhaps it was just the stories we tell one another in our daily lives. It's sort of amazing, even to me, how much marketing colors the way we see the world--our reaction (either way) to this chart is proof of it.

Un essaim de puces

To quote Sarah Jones, the market has become a swarm of fleas (it sounds better in French, for sure).

Short attention spans, flitting from place to place, a hit and run culture.

Marketers are more like circus ringleaders than ever before. Far better, it seems, to concentrate on the few (fleas) willing to slow down, the few willing to stop acting that way and actually pay attention and stick around.

March 21, 2011

Reject the tyranny of being picked: pick yourself

Amanda Hocking is making a million dollars a year publishing her own work to the Kindle. No publisher.

Rebecca Black has reached more than 15,000,000 listeners, like it or not, without a record label.

Are we better off without gatekeepers? Well, it was gatekeepers that brought us the unforgettable lyrics of Terry Jacks in 1974, and it's gatekeepers that are spending a fortune bringing out pop songs and books that don't sell.

I'm not sure that this is even the right question. Whether or not we're better off, the fact is that the gatekeepers--the pickers--are reeling, losing power and fading away. What are you going to do about it?

It's a cultural instinct to wait to get picked. To seek out the permission and authority that comes from a publisher or talk show host or even a blogger saying, "I pick you." Once you reject that impulse and realize that no one is going to select you--that Prince Charming has chosen another house--then you can actually get to work.

If you're hoping that the HR people you sent your resume to are about to pick you, it's going to be a long wait. Once you understand that there are problems just waiting to be solved, once you realize that you have all the tools and all the permission you need, then opportunities to contribute abound.

No one is going to pick you. Pick yourself.

March 20, 2011

Idea tourism

It's possible for a tourist to visit Times Square in New York City, see nothing new or unexpected, and leave the city unchanged.

Same with the Eiffel Tower in Paris or a shopping mall in Dubai. Tourism doesn't always open your mind, but when it works the way it supposed to, it sure does.

Which brings us to the notion of idea tourism.

It's possible to do a drive-by of some of the big ideas of science or politics or technology and see only what you want to see. I don't think there's a lot of point in that. If you want to truly understand Darwin, then go to a lab and do some experiments. If you want to understand a gun lover, go to a shooting range for an afternoon. If you want to see how social networking will actually change the way ideas spread, go use it. Intensely, and with a purpose in mind.

Only when we try the idea on for size and actually use it do we understand it. With more ideas offering visitation rights than ever before, learning how empathize with an idea is critical.

March 19, 2011

Better than it sounds

Mark Twain said that Wagner wrote music that was better than it sounds.

It's an interesting way to think about marketing. Is your product better than it sounds, or does it sound better than it is?

We call the first a discovery, something worthy of word of mouth. The second? Hype.

March 18, 2011

Coughing is heckling

The other night I heard Keith Jarrett stop a concert mid-note. While the hall had been surprisingly silent during the performance, the song he was playing was quiet and downbeat and we (and especially he) could hear an increasing chorus of coughs.

"Coughs?," you might wonder... "No one coughs on purpose. Anyway, there are thousands of people in the hall, of course there are going to be coughs."

But how come no one was coughing during the introductions or the upbeat songs or during the awkward moments when Keith stopped playing?

No, a cough is not as overt or aggressive as shouting down the performer. Nevertheless, it's heckling.

Just like it's heckling when someone is tweeting during a meeting you're running, or refusing to make eye contact during a sales call. Your work is an act of co-creation, and if the other party isn't egging you on, engaging wth you and doing their part, then it's as if they're actively tearing you down.

Yes, you're a professional. So is Jarrett. A professional at Carnegie Hall has no business stopping a concert over some coughing. But in many ways, I'm glad he did. He made it clar that for him, it's personal. It's a useful message for all of us, a message about understanding that our responsibility goes beyond buying a ticket for the concert or warming a chair in the meeting. If we're going to demand that our partners push to new levels, we have to go for the ride, all the way, or not at all.

March 17, 2011

Protecting the soft spot

We all have one. Or more than one. It's that place where we can get hurt, the one we seek to defend.

For some people, it's a boss calling us out in front of our peers. For someone else, it's an angry customer. For someone else, it's being confronted with a problem you can solve--but that the effort just seems too great.

The key question is this: how much does the act of protecting the soft spot actually make it more likely you will be hurt?

It turns out that the more you angle yourself, the harder you work to protect the soft spot, the more likely it is that you'll get hurt.

All the time and effort you put into ducking and hiding and holding and avoiding might be sending the market a signal... the irony of your effort is that it's probably making the problem worse.

March 16, 2011

Kraft singles

Here's a ubiquitous food that succeeds because it's precisely in the center, perfectly normal, exactly the regular kind. No kid whines about how weird they are.

If you're Kraft, this is a good place to be. Singles mint money. My friend Nancy worked on this brand. It's a miracle.

If you're anyone else, forget about becoming more normal than they are, more regular than the regular kind. That slot is taken.

Most mature markets have their own version of Kraft Singles. The challenge for an insurgent is not to try to battle the incumbent for the slot of normal. The challenge is to be edgy and remarkable and to have the market move its center to you.

March 15, 2011

Live in New York City

One of my favorite events is coming up April 11th.

I'll be spending the day at the Fabulous Helen Mills Theatre in New York. Tickets go on sale today.

This is a live, ad-lib event, driven completely by your questions and issues and opportunities. It's limited to just a hundred tickets, and it always sells out.

If you type in the discount code: sethsentme you'll save another 10%.

PS if you haven't seen the new book yet, it's been on the Amazon top 100 for the last two weeks--the most successful book launch we've ever done. There's even a 52 pack. Thanks for spreading the word.

Seth Godin's Blog

- Seth Godin's profile

- 6535 followers