Iain Cameron's Blog, page 2

June 27, 2018

Publishers are paying writers a pittance

An interesting article from the Guardian 27/06/18

Philip Pullman, Antony Beevor and Sally Gardner are calling on publishers to increase payments to authors, after a survey of more than 5,500 professional writers revealed a dramatic fall in the number able to make a living from their work.

The latest report by the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS), due to be published on Thursday, shows median earnings for professional writers have plummeted by 42% since 2005 to under £10,500 a year, well below the minimum annual income of £17,900 recommended by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Women fare worse, according to the survey, earning 75% of what their male counterparts do, a 3% drop since 2013 when the last ALCS survey was conducted.

Based on a standard 35-hour week, the average full-time writer earns only £5.73 per hour, £2 less than the UK minimum wage for those over 25. As a result, the number of professional writers whose income comes solely from writing has plummeted to just 13%, down from 40% in 2005.

The median income of the writers surveyed – including part-time and occasional authors – has declined in real terms to £3,000 a year, down 33% since the last survey in 2013, and 49% since the first ALCS report in 2005. Professional writers are defined as those who dedicate more than half their working hours to writing.

Pullman, Beevor and Gardner claim the crash in number of professional writers is threatening the diversity and quality of literary culture in the UK. They lay the blame at the door of publishers and online booksellers, which over the same period have failed to share a greater slice of their rocketing profits. In 2016, UK publishers’ sales of books and journals rose 7% to £4.8bn, a trend repeated in 2017 as UK books sales alone passed the £2bn mark. Since 2005, Amazon’s global turnover has risen from $8.49bn (£6.4bn) to $177.87bn.

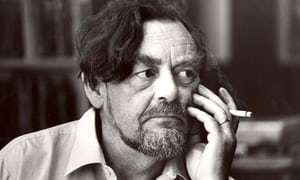

“The word exploitation comes to mind,” said Pullman, bestselling author of the His Dark Materials series and president of the Society of Authors. “Many of us are being treated badly because some of those who bring our books to the public are acting without conscience and with no thought for the future of the ecology of the trade as a whole … This matters because the intellectual, emotional and artistic health of the nation matters, and those who write contribute to the task of sustaining it.”

Amanda Craig, whose latest book, The Lie of the Land, was published in 2017, said: “Women invariably do the majority of childrearing, which can mean they have 15 years or more of lower earning, particularly in something like fiction, which demands such a lot of concentration,” she said.

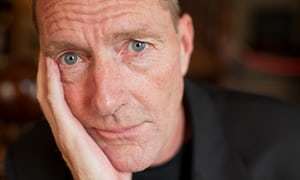

Decline in earnings is threatening diversity among writers, says Stalingrad author Antony Beevor. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Decline in earnings is threatening diversity among writers, says Stalingrad author Antony Beevor. Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Beevor, author of breakout bestseller Stalingrad, echoes Pullman’s concerns, adding that non-fiction authors face a particular problem if they have little money to fund their research. “Stalingrad took four years’ work, which was funded by publishing deals from the UK and abroad,” Beevor said. “I had tried writing part-time in the evening, but you are too knackered at the end of the day and I couldn’t do it.”

He added that the decline in earnings threatened the diversity among writers and would favour economic advantage over talent. “We need professional writers, because otherwise only those with other sources of income will be able to write.”

Nicola Solomon, chief executive of the Society of Authors, criticises publishers and Amazon for not sharing a greater percentage of their booming profits with the people who supply their raw material. “What concerns us is that during the same period that we see authors’ earnings plummet, the large publishers are seeing their sales rocket,” she said.

Solomon estimates that payment of authors accounted for a mere 3% of publishers’ turnover in 2016. “The industry pays so little for the raw material. Publishers talk about diversity then pay lip service to sustaining writers’ careers. They have a responsibility to see that authors are properly paid and their earnings do not go down,” she added.

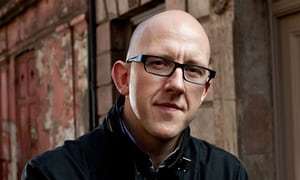

‘When I started you could still make an okay living from writing’ … Sally Gardner. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

‘When I started you could still make an okay living from writing’ … Sally Gardner. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the Guardian

“When I started you could still make an okay living from writing. You can’t do that now,” said Sally Gardner, whose bestselling novel Maggot Moon won the Carnegie medal and Costa children’s book award, but came 20 years after her first book.

As a result, she said, the ability of authors to craft their ideas over years and write books that tackled important questions had been seriously undermined. “Now the publishing business wants bestselling novels at whatever cost, but to develop talent and great writing you need patience, encouragement and financial support,” she added.

Publishers being risk-averse had led to a situation where celebrity authors were leaving others with a smaller pool of money to compete for, Gardner added. As a result, authors were finding it harder to get novels that asked big questions into print.

Tony Bradman, children’s writer and chair of the ALCS, said there would be long-term consequences to the underfunding of writers. “It is shortsighted in business terms to say it doesn’t matter [if we have few professional writers], just throw money at the big names and it will work,” the Dilly the Dinosaur creator said. “If they don’t work, where are the authors to replace them?”

The 2018 ALCS survey covers writers from fields including stage and screen, but authors appear to fare worse than their counterparts in the creative arts. “If I had to rely on being a novelist, I would be skint,” said Jonathan Harvey, a novelist who supports his books with a day job as a playwright – his latest is the Dusty Springfield musical called Dusty – and as head scriptwriter for Coronation Street.

“It wasn’t until my 11th book that I started to get royalties,” he said. “How many people can afford to go that long without money from another source?” In contrast, he continues to earn 8%-10% of box office receipts from new productions of his debut play, Beautiful Thing, which opened in 1993.

“Authors are not a special case, deserving of more sympathy than many other groups,” said Pullman. “We are a particular case of a general degradation of the quality of life, and we are not going to stop pointing it out, because we speak for many other groups as well.”

May 1, 2018

Top Writers Choose Their Perfect Crime

On Beulah Height by Reginald Hill

Val McDermid

This is the perfect crime novel. It’s beautifully written – elegiac, emotionally intelligent, evocative of the landscape and history that holds its characters in thrall – and its clever plotting delivers a genuine shock. There’s intellectual satisfaction in working out a plot involving disappearing children, whose counterpoint is Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder. There’s darkness and light, fear and relief. And then there’s the cross-grained pairing of Dalziel and Pascoe. Everything about this book is spot on.

Although Hill’s roots were firmly in the traditional English detective novel, he brought to it an ambivalence and ambiguity that allowed him to display the complexities of contemporary life. He created characters who changed and developed in response to their experiences. I urge you to read this with a glass of Andy Dalziel’s favourite Highland Park whisky.

• Insidious Intent by Val McDermid is published by Sphere.

The Damned and the Destroyed by Kenneth Orvis

Lee Child

My formative reading was before the internet, before fanzines, before also-boughts, so for me the “best ever” is inevitably influenced by the gloriously chanced-upon lucky finds, the greatest of which was a 60 cent Belmont US paperback, bought in an import record shop on a back street in Birmingham in 1969. It had a lurid purple cover, and an irresistible strapline: “She was beautiful, young, blonde, and a junkie … I had to help her!” It turned out to be Canadian, set in Montreal. The hero was a solid stiff named Maxwell Dent. The villain was a dealer named The Back Man. The blonde had an older sister. Dent’s sidekicks were jazz pianists. The story was patient, suspenseful, educational and utterly superb. In many ways it’s the target I still aim at.

• The Midnight Line by Lee Child is published by Bantam.

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

Ian Rankin

Does this count as a crime novel? I think so. Dickens presents us with a mazey mystery, a shocking murder, a charismatic police detective, a slippery lawyer and a plethora of other memorable characters – many of whom are suspects. The story has pace and humour, is bitingly satirical about the English legal process, and also touches on large moral and political themes. As in all great crime novels, the central mystery is a driver for a broad and deep investigation of society and culture. And there’s a vibrant sense of place, too – in this case, London, a city built on secret connections, a location Dickens knows right down to its dark, beating heart.

• Rather Be the Devil by Ian Rankin is published by Orion. Siege Mentality by Chris Brookmyre is published by Little, Brown.

The Hollow by Agatha Christie

Sophie Hannah

This is my current favourite, in its own way just as good as Murder on the Orient Express. As well as being a perfectly constructed mystery, it’s a gripping, acutely observed story about a group of people, their ambitions, loves and regrets. The characters are vividly alive, even the more minor ones, and the pace is expertly handled. The outdoor swimming pool scene in which Poirot discovers the murder is, I think, the most memorable discovery-of-the-body scene in all of crime fiction. Interestingly, Christie is said to have believed that the novel would have been better without Poirot. His presence here is handled differently – he feels at one remove from the action for much of the time – but it works brilliantly, since he is the stranger who must decipher the baffling goings on in the Angkatell family. The murderer’s reaction to being confronted by Poirot is pure genius. It would have been so easy to give that character, once exposed, the most obvious motivation, but the contents of this killer’s mind turn out to be much more interesting …

• Did You See Melody by Sophie Hannah is published by Hodder.

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

SJ Watson

I first came to Rebecca, published in 1938, with one of the most recognisable first lines in literature, not knowing exactly what to expect. That it was a classic I was in no doubt, but a classic what? I suspected a drama, possibly a romance, a book heavy on character but light on plot and one I’d read and then forget. How wrong I was.

It is a dark, brooding psychological thriller, hauntingly beautiful, literature yes, but with a killer plot. I loved everything about it. The way Du Maurier slowly twists the screw until we have no idea who to trust, the fact that the title character never appears and exists only as an absence at the heart of the book, the fact that the narrator herself is unnamed throughout. But, more importantly, this thriller is an exploration of power, of the men who have it and the women who don’t, and the secrets told to preserve it.

• Second Life by SJ Watson is published by Black Swan.

Mystic River by Dennis Lehane

James Lee Burke

To my mind this is the best crime novel written in the English language. Lehane describes horrible events with poetic lines that somehow heal the injury that his subject matter involves, not unlike Shakespeare or the creators of the King James Old Testament. That’s not a hyper-bolic statement. His use of metaphysical imagery is obviously influenced by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Mystic River is one for the ages.

• Robicheaux by James Lee Burke is published by Orion.

The Expendable Man by Dorothy B Hughes

Sara Paretsky

Author Sara Paretsky for Arts. Photo by Linda Nylind. 15/7/2015.

Author Sara Paretsky for Arts. Photo by Linda Nylind. 15/7/2015.Today, Hughes is remembered for In a Lonely Place (1947) – Bogart starred in the 1950 film version. My personal favourite is The Expendable Man(1963). Hughes lived in New Mexico and her love of its bleak landscape comes through in carefully painted details. She knows how to use the land sparingly, so it creates mood. The narrative shifts from the sandscape to the doctor, who reluctantly picks up a teen hitchhiker. When she’s found dead a day later, he’s the chief suspect, and the secrets we know he’s harbouring from the first page are slowly revealed.

Hughes’s novels crackle with menace. Like a Bauhaus devotee, she understood that in creating suspense, less is more. Insinuation, not graphic detail, gives her books an edge of true terror. She’s the master we all could learn from.

• Fallout by Sara Paretsky is published by Hodder.

Killing Floor by Lee Child

Dreda Say Mitchell

What is it about any particular novel that means you’re so engrossed that you miss your bus stop or stay up way past your bedtime? A spare, concise style that doesn’t waste a word. A striking lead character who manages to be both traditional and original. A plot that’s put together like a Swiss watch. Child’s debut has all these things, but like all great crime novels it has the x-factor.

In the case of Killing Floor that factor is a righteous anger, rooted in personal experience, that makes the book shake in your hands. It’s the story of a military policeman who loses his job and gets kicked to the kerb. Jack Reacher becomes a Clint Eastwood-style loner who rides into town and makes it his business to dish out justice and protect the underdog, but without the usual props of cynicism or alcohol. We can all identify with that anger and with that thirst for justice. We don’t see much of the latter in real life. At least in Killing Floor we do.

• Blood Daughter by Dreda Say Mitchell is published by Hodder.

The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler

Benjamin Black (John Banville)

The Long Goodbye is not the most polished, and certainly not the most convincingly plotted, of Chandler’s novels, but it is the most heartfelt. This may seem an odd epithet to apply to one of the great practitioners of “hard-boiled” crime fiction. The fact is, Chandler was not hard-boiled at all, but a late romantic artist exquisitely attuned to the bittersweet melancholy of post-Depression America. His closest literary cousin is F Scott Fitzgerald.

Philip Marlowe’s love – and surely it is nothing less than love – for the disreputable Terry Lennox is the core of the book, the rhapsodic theme that transcends and redeems the creaky storyline and the somewhat cliched characterisation. And if Lennox is a variant of Jay Gatsby, and Marlowe a stand in for Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald’s self-effacing but ever-present narrator, then Roger Wade, the drink-soaked churner-out of potboilers that he despises, is an all too recognisable portrait of Chandler himself, and a vengefully caricatured one at that. However, be assured that any pot The Long Goodbye might boil is fashioned from hammered bronze.

• Prague Nights by Benjamin Black is published by Viking.

Love in Amsterdam by Nicolas Freeling

Ann Cleeves

Although Nicolas Freeling wrote in English he was a European by choice – an itinerant chef who roamed between postwar France, Belgium and Holland, and who instilled in me a passion for crime set in foreign places. He detested the rules of the traditional British detective novel: stories in which plot seemed to be paramount. Love in Amsterdam (1962) is Freeling’s first novel and it breaks those rules both in terms of structure and of theme.

It is a tale of sexual obsession and much of the book is a conversation between the suspect, Martin, who’s been accused of killing his former lover, and the cop. Van der Valk, Freeling’s detective, is a rule-breaker too, curious and compassionate, and although we see his investigative skills in later books, here his interrogation is almost that of a psychologist, teasing the truth from Martin, forcing him to confront his destructive relationship with the victim.

• The Seagull by Ann Cleeves is published by Pan.

L aidlaw by William McIlvanney

Chris Brookmyre

I first read Laidlaw in 1990, shortly after moving to London, when I was aching for something with the flavour of home, and what a gamey, pungent flavour McIlvanney’s novel served up. A sense of place is crucial to crime fiction, and Laidlaw brought Glasgow to life more viscerally than any book I had read before: the good and the bad, the language and the humour, the violence and the drinking.

Laidlaw’s turf is a male hierarchy ruled by unwritten codes of honour, a milieu of pubs and hard men rendered so convincingly by McIlvanney’s taut prose. “His face looked like an argument you couldn’t win,” he writes of one character, encapsulating not only the man’s appearance but his entire biography in a mere nine words.

This book made me realise that pacey, streetwise thrillers didn’t have to be American: we had mean streets enough of our own. It emboldened me to write about the places I knew and in my own accent.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Laura Lippman

I’m going to claim Lolita for crime fiction, something I never used to do. But it has kidnapping, murder and – it’s important to use this term – rape. It also has multiple allusions to Edgar Allan Poe and even hides an important clue – well, not exactly in plain sight, but in the text of, yes, a purloined letter. And now we know, thanks to the dogged scholarship of Sarah Weinman, that it was based on a real case in the United States. (Weinman’s book, The Real Lolita, will be published later this year.)

Dorothy Parker meant well when she said Lolita was a book about love, but, no – it’s about the rape of a child by a solipsistic paedophile who rationalises his actions, another crime that is too often hidden in plain sight. Some think that calling Lolita a crime novel cheapens it, but I think it elevates the book, reminds us of the pedestrian ugliness that is always there, thrumming beneath the beautiful language.

• Sunburn by Laura Lippman is published by Faber.

The Moving Target by Ross Macdonald

Donna Leon

Ross Macdonald, an American who wrote in the 60s and 70s, has enchanted me since then with the beauty of his writing and the decency of his protagonist, Lew Archer. I envy him his prose: easy, elegant, at times poetically beautiful. I also admire the absence of violence in the novels, for he usually follows Aristotle’s admonition that gore be kept out of the view of the audience. When Archer discovers the various wicked things one person has done to another, he does not linger in describing it but makes it clear how his protagonist mourns not only the loss of human life but also the loss of humanity that leads to it.

Macdonald’s plotting is elegant: often, as Archer searches for the motive for today’s crime, he unearths a past injustice that has returned to haunt the present and provoke its violence. His sympathy for the victims is endless, as is his empathy for some of the killers.

• The Temptation of Forgiveness by Donna Leon is published by William Heinemann.

The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins

Nicci French

With The Woman in White (1859-60) and The Moonstone (1868), Wilkie Collins basically invented the thriller form. The first features a woman wandering out of the fog, madness, stolen identity, one of the great villains – Fosco, corpulent, witty, with pet mice in his pockets – and a strong, unfeminine heroine with a moustache. The Moonstone has a world weary detective, an apparently unsolvable crime and a story told from multiple points of view. Pedants might point out that Poe was a co-inventor (and an earlier one).They might also point out that after an extraordinary psychological duel between Marian Halcombe and Fosco in the first half of the book, Collins almost seems to lose interest. And that the solution in The Moonstone is an outrageous cheat. No matter. Those of us writing in the form are still in his debt – and we’re still reading and rereading his uncanny and glorious books.

• Sunday Morning Coming Down by Nicci French is published by Penguin.

The Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle

Sam Bourne (Jonathan Freedland)

The trouble with a classic, especially one as frequently adapted as this, is you can lose sight of the original. And yet, looming over the Cumberbatches and Rathbones, there lives my own personal Sherlock Holmes, the one who took shape when I read the story as a schoolboy. No matter how many film or TV versions I come across, none can match the thrill of that first encounter.

And there’s a reason why producers and directors keep returning to Baskerville Hall. The book is a perfectly executed crime story: red herrings dropped in just the right places, a location full of mist and menace, a tangle of family secrets, the murderer’s apparently ingenious plan and, at the centre, an enigmatic, eccentric and brilliant detective. It is a recipe for pleasure that made me gasp as a child – and it’s never stopped working.

• To Kill the President by Sam Bourne is published by HarperCollins.

A Fatal Inversion by Barbara Vine (Ruth Rendell)

Erin Kelly

Summer 1976: student Adam inherits an isolated Suffolk house from a distant uncle. The bohemian commune he dreams of goes horribly wrong. Ten years later, the bodies of a woman and child are discovered in the hall’s animal cemetery. But which woman? Whose child?

Rendell was best known for her Chief Inspector Wexford procedural novels but it’s the standalone psychological thrillers she wrote as Barbara Vine that have me by the heart. A Fatal Inversion is arguably the definitive Vine: set partly in the past, substantial in theme and language as well as length. Not a classic whodunit but who-was-it-done-to, ingeniously plotted using flashback and switching viewpoints to constantly wrong-foot the reader.

It is a murder investigation, but seen from the suspects’ viewpoint rather than the detective’s. This is the kind of crime I like to read (and write). This book has it all; murder, suspense, sex, property porn and a last-page twist that still makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up.

What set Rendell apart was an underpinning of perfect psychological plausibility. She understood better than anyone I’ve ever read how petty obsession can spiral into violence. Rendell dealt in Middle England rather than the marginalised, with loss of control rather than premeditation. The violence is sparing and all the more chilling for it, letting readers’ imaginations do the real dirty work.

• He Said/She Said by Erin Kelly is published by Hodder.

A Quiet Flame by Philip Kerr

Abir Mukherjee

It was a tragedy when Kerr, one of my heroes, passed away earlier this year. He was a prodigious talent, but he’ll be best remembered for his fantastic antihero, Bernie Gunther, an investigator in Nazi Germany and in the postwar period. I love novels with an ambiguous, conflicted protagonist and, for me, Gunther is the gold standard. My favourite is A Quiet Flame, in which Bernie finds himself in Argentina, alongside a bunch of unsavoury characters including Adolf Eichmann. Bernie is tasked with hunting down a serial killer targeting young girls in a method very similar to another crime he investigated back in Berlin.

• A Necessary Evil by Abir Mukherjee is published by Vintage.

The Talented Mr Ripley by Patricia Highsmith

Sabine Durrant

It’s slightly cheating, choosing Ripley, because he comes with five novels, not one, and they are all equally gripping, tantalising and psychologically fascinating. Across the Ripliad, our hero matures – his weird, glinting, almost masochistic relationship with guilt twists and mutates – but it is in The Talented Mr Ripley that he first crosses the Rubicon from conman to psychopath. Ripley, having befriended and then taken on the identity of rich, idle Dickie, ducks and dives across Italy, using his wits to outrun the consequences of his actions and the devil of his own nature. Highsmith’s writing is deceptively simple – as when a smile is “deliberately hurled” across a table. But it’s her understanding of psychology that makes the novel so great. Like all the best confidence tricksters, Ripley reads people, each nervous twitch, each self-regarding simper, using every moment of weakness for his own gain. Highsmith does the same with the reader. She draws in your sympathies (Ripley’s right, isn’t he? How aloof and superior this character is), so that when the bludgeon comes out, half a page later, you are somehow complicit in the crime. Chilling perfection.

• Take Me In by Sabine Durrant is out from Mulholland in June.

Crim e and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Graeme Macrae Burnet

Crime and Punishment is kingpin of the crime fiction prison yard. It’s a teeming, Rabelaisian sprawl, but from the moment Raskolnikov leaves his garret and sets off towards the Kokushkin Bridge it grabs the reader by the lapels. The murder scene, when it comes, is at once farcical, horrifying and enthralling. Raskolnikov is by turns irascible, compassionate, mean-spirited and astute. He infuriates, and commits heinous crimes, but Dostoevsky still contrives to make us root for him.

Of course, it is no whodunnit. Instead, in common with much of the greatest crime fiction, its fascination lies in the exploration of the machinations of the mind of a killer – it’s concerned with the psychological impact of the crime rather than the unravelling of a mystery. The big questions it asks are those of guilt, free will and redemption and it’s this ambition that makes it not only the greatest crime novel, but perhaps the greatest of all novels.

• The Accident on the A35 by Graeme Macrae Burnet is published by Contraband.

A Place of Execution by Val McDermid

Susie Steiner

This book is as close to perfection as I’ve come across. Structurally it’s extremely tightly woven and as psychological suspense, it pretty much has everything. Remote rural community harbouring secrets? Check. Dual time narrative – the original crime investigation of 1963 and current day? Check. Intrepid female lead, uncovering the truth? Check. Killer twist? Check. Ruth Rendell agreed it was “one of the best detective stories I’ve read”.

I read it a long time ago, before I became a crime writer myself, yet when I think about it now, it seems more like a classic novel than a contemporary one. What stays in the mind is the Peak District community of Scarsdale, the investigator as outsider trying to permeate its secrets. And the sheer quality of the writing.

• Persons Unknown by Susie Steiner is published by Borough.

A Perfect Spy by John le Carré

Jeffery Deaver

Seamlessly blending piercing psychological drama, solid procedural and geopolitical thriller plotting, le Carré tells his tales in a breathtaking style he manages to make both muscular and elegant. A Perfect Spy is perhaps the best fictional examination of a father-son relationship penned to date. And his dissection of American foreign policy (in any number of his works) should be required reading in the US state department.

• The Burial Hour by Jeffery Deaver is published by Hodder.

Gorky Park by Martin Cruz Smith

Jacob Ross

It was Cruz Smith’s Arkady Renko series that showed me the possibilities of “voice” and “character attitude” in crime writing and how those two elements can be brought together to create a truly memorable novel. In Gorky Park we are navigating the edgy, fractious world of cold war Moscow. There is something wonderfully distinctive about the Russian detective’s way of being and seeing. I am struck by the precision and insight in his interactions with others and himself and that honed cynicism that is never moralistic or judgmental. As Michael Connelly pointed out, “a crime novel – like any story – succeeds or fails on the basis of character”. Renko confirms this for me every time. It is an incredible feat of character portrayal.

• The Bone Readers by Jacob Ross is published by Peepal Tree.

Silence of the Grave by Arnaldur Indriðason

Yrsa Sigurðardóttir

Jar City was the first Icelandic crime novel to become a critical and commercial success. Published in Icelandic in 2001 (and translated into English by Bernard Scudder in 2006), Silence of the Grave is the second in the series, and proved Arnaldur Indriðason to be one of the world’s finest contemporary crime fiction writers. The book centres on the investigation into the origins of a skeleton found at a building site. This is intriguing enough to keep one glued to the pages, as is the flawed yet endearing protagonist, the policeman Erlendur. But it is a second storyline – which revolves around domestic abuse and its effect on the family involved – that really elevates the novel. It is heart wrenching, agonisingly disturbing and so utterly convincing that one feels present in this horrible household.

• The Reckoning by Yrsa Sigurðardóttir is out from Hodder in May.

The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M Cain

Denise Mina

An amoral drifter arrives at a truck stop looking for food or work and meets his soulmate, the wife of the cafe owner. The sultry self-loathing of the protagonist is mirrored by the woman and they begin a cruel, careless affair and devise a plan to murder her husband. The staccato first person delivery gives the book a thrilling, urgent tone. Neither of the central characters is given a back story and their motives are base. So far, so pulp noir, but Cain does something extraordinary within that. They are redeemed by their loyalty to each other. It takes an hour to read but you’ll never forget it

• The Long Drop by Denise Mina is published by Vintage.

Gorky Park by Martin Cruz Smith

Mick Herron

This is the high-water mark of the genre, for me. Martin Cruz Smith took a familiar trope – a good man trying to keep his head down and do his job, despite the corruption all around him – and made something entirely fresh, entirely new. What begins as a murder mystery becomes a cold war thriller unlike any that preceded it, and if the label “game-changer” had existed back in the 80s, here it would have found its perfect fit. Gorky Park is perhaps the most humane thriller I’ve ever read, offering a fascinating glimpse of a society in slow-motion collapse, and its thrills never pall with rereading; every time the snow starts to melt, revealing those three corpses within earshot of the skating rink, I’m hooked again. The key to its success is its hero, Arkady Renko: brave, lonely and utterly sympathetic. “He’s a good instrument. I work better when I’m working with him,” Smith once said. We could all use such tools.

• London Rules by Nick Herron is out from John Murray in August.

• The Theakston Old Peculier crime writing festival, with Lee Child as programming chair, is at The Old Swan, Harrogate, 19-22 July. harrogateinternationalfestivals.com.

April 17, 2018

Why thrillers are leaving other books for dead

Taken From The Guardian 15/04/18

For years, crime fiction titles have topped the bestseller lists and library lending tables. That sales of the genre have now overtaken general fiction, as revealed at the London Book Fair last week, comes as no surprise to its readers, practitioners, critics and industry professionals.

We’ve always recognised its reach, dynamism, integrity and, increasingly, diversity. Yet its rise, and indeed acceptance, is still a mystery to some, with any number of narratives seeking to understand the phenomenon. This is about as helpful as trying to define exactly what makes a bestseller a bestseller, and, perhaps more important, how to spot the next big thing. At best it’s a lucky amalgamation; so many factors come into play. Being in the right place at the right time, with the right idea, and talent, might be one answer. But how the hell do you come up with the right idea?

There are reasons, however, why the crime genre is so effective as a fictional narrative form, often well away from the glitz of the charts, and why it translates brilliantly on to the screen, both small and large. And there is a growing critical sense as to why it’s so popular now. This has little to do with the old idea, now resurfacing, that in times of uncertainty we seek comfort, redemption and resolution; a place where good triumphs over evil and order is restored. Classic detective fiction, which came to the fore between the world wars, was built on those ideals, along with some very rigid and peculiar rules dreamed up by writers such as Ronald Knox and SS Van Dine.

As any serious writer knows, rules are there to be broken. No artist wants to be bound, or dictated to. This doesn’t mean that writers should ignore basic narrative concepts of purpose, pace and plot. Or, of course, character. I talk to my crime fiction students a lot about “menace and motivation”; simply, having characters want things, and then having things put in their way.

Readers, and viewers, like to be engaged, excited even. Writing something entertaining has an attraction, maybe missed by those who believe that if something is wildly popular it is less culturally worthy or intellectually challenging. Raymond Chandler, in his polemical 1950 essay The Simple Art of Murder, railed against Dorothy L Sayers, who suggested there was such a thing as a “literature of expression” and a “literature of escape”. His riposte was that “everything written with vitality expresses that vitality; there are no dull subjects only dull minds”.

Crime fiction has always been broad, with current parallels. A course we run at the University of East Anglia begins with a study of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express and James M Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, both from 1934. They couldn’t be more different. One is an absurd “locked room” whodunnit, the other a chilling first-person confession from someone awaiting execution. Effectively, crime fiction split, taking a tidy, restorative Christie, or unruly, apocalyptic Cain path.

Crime fiction in its broadest sense has always been hugely influential, particularly among so-called “literary” writers. William Faulkner compared Georges Simenon to Chekhov. WH Auden adored Christie and Sayers. André Gide was an admirer of Patricia Highsmith, Albert Camus based The Stranger on The Postman Always Rings Twice, while Eleanor Catton drew on Cain’s Double Indemnity for her Man Booker prize-winning The Luminaries. Martin Amis’s novella Night Train is a homage to Elmore Leonard.

John Banville (another Man Booker winner), who writes crime fiction under the pseudonym Benjamin Black, has said that the “modernist experiment is over”, and the literary novel is “in the doldrums”, whereas crime fiction reasserts the traditional literary values of “plot, character and dialogue”. Banville’s reception among the crime-writing fraternity got off to a difficult start when he suggested at a festival that he wrote his crime fiction quickly, and his literary fiction slowly, inadvertently implying that it was easier.

While the essence of writing crime fiction might come down to speed and fluency, crafting and control are vital. It’s not easy and few do it really well. A crime novel that works is as taut as a drum. Plus, readers can quickly sniff out a fraud – someone writing up or down, or for the money, and it’s now a very competitive market.

Approaching the right idea and themes seems to depend as much on prescience as talent. Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl was instrumental in determining the popularity of what’s become known, thanks to Julia Crouch, as “domestic noir”. This is a development of the psychological thriller, which has its roots in early 19th-century gothic tales such as the satirical Northanger Abbey (interestingly reimagined by Val McDermid, one of this year’s Man Booker judges).

Gone Girl is every bit as dark and disturbing, and knowing – critically, socially and politically – as Flynn’s previous two novels, Dark Places and Sharp Objects. Paula Hawkins’s The Girl on the Train is also extraordinarily dark and disturbing, and adapted successfully on to the big screen.

Neither landmark books, nor their many imitators, are what you’d call comforting. One of their main appeals is the fact that they make you feel uncomfortable; that they invade your headspace, adding drama, fear and anxiety. They sweep you away from the everyday. They heighten your senses, and they surprise, not least because they are tackling a world we thought we knew intimately.

That crime fiction can still accommodate neat police procedural, dark psychological thriller and everything between, above and beyond (and there are some very interesting crime, horror and speculative fiction crossovers emerging), while continuing to develop and being ever more popular, suggests it’s the fictional form of our times.

It could still, however, look far wider. A new wave of talented and ethnically diverse crime writers includes Winnie M Li, Jacob Ross, Leye Adenle and Amer Anwar. Work from India, Nigeria, Singapore, South Korea and Brazil is gaining global attention. Film and TV adaptations might travel further and faster than the book, but the fundamental concept of crime drama is the same: life and death. Murder, as Chandler acknowledged in his essay, is serious business. It’s the telling, the understanding, that changes.

Henry Sutton is a senior lecturer in creative writing at UEA and director of the MA Crime Fiction. His novel, Time to Win, written under the pseudonym Harry Brett, is published in paperback on 26 April by Corsair

March 17, 2018

Val McDermid on Trump and Treasure Island

The author on poetry for Donald Trump, the crime novel that most influenced her – and why she wishes that she had written Treasure Island

The book I am currently reading

I am one of the judges for this year’s Man Booker prize, so it would be extremely indiscreet of me to reveal what I’m currently reading, except that it’s a novel published in the current period of eligibility.

The book that changed my life

Many books have had a profound impact on me but Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics transformed the way I read and also the way I live. It was my first encounter with feminism, and a radical approach to literary criticism. It felt like an explosion inside my head.

The book I wish I’d written

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. It has everything: archetypal characters, atmospheric settings, a terrific story and evocative prose. And an open ending – Long John Silver is still alive, there’s still more treasure to be found. What a gift for the reader’s imagination.

The book that influenced on my work

William McIlvanney’s Laidlaw was the first crime novel I’d read that dealt with the lives of people I recognised. They spoke in the speech rhythms I’d grown up hearing, theirs were the concerns of ordinary people. It showed me that it was possible to write crime fiction that was rooted in my reality. And it’s as fresh and inspirational today as it was 40 years ago.

The book that changed my mind

I’d always been scornful of fantasy until I read my first Terry Pratchett novel, Mort, the fourth in the Discworld series. That began a love affair that continued until his untimely death. Clever, satirical and bursting with extraordinary creativity, they never grew stale.

The book that is most underrated

Anything by Josephine Tey. She is admired by crime writers but too few readers have discovered her talents.

The last book that made me cry

Close Your Eyes by Michael Robotham. The eighth of his Joe O’Loughlin novels delivers a sucker punch at the end that reduced me to tears. Good series fiction makes us invest in characters and care about their fate.

The last book that made me laugh

The Beautiful Poetry of Donald Trump by Robert Sears. I have composed my own accompanying haiku:

Poetry of Trump –

We keep it in the toilet.

It helps us perform.

The book I couldn’t finish

It goes against my Scottish Presbyterian upbringing, but life is too short to waste on books that don’t engage my heart or mind. So I regularly transfer books to the charity shop pile because they haven’t earned a place on my shelves.

The book I give as a gift

Scotland the Dreich by Alan McCredie. It’s funny and it’s an antidote to the romantic image that’s so often propagated of my country.

The book I’d most like to be remembered for

I have to believe the best is still to come. So, the one after the one I’m writing now. Or the one after that.

March 5, 2018

Audiobooks Are Like Buses…

Hot on the heals of releasing Red Red Wine on audiobook (see this Blog 10/01/18), One Last Lesson will be published in audiobook form in a few days time, 08/02/18. One Last Lesson is the first book in the DI Henderson series and being a bit shorter than Red Red Wine in audiobook terms, (8 hours length versus nearly 10 hours for Red Red Wine) it’s cheaper at £14.87. It is narrated by Dave Gillies, a Glasgow-based producer, composer and voice-over artist.

If you are not a member of Audible and you like audiobooks, it costs £7.99 per month in the UK. For this, you receive a free audiobook to start, which you can keep, and then you can download a new audiobook once a month. Members also receive discounted offers. You can sign up through the Amazon website. If, for example, you would like to download One Last lesson, click here and then click on the bar at the far right, Start Your Free Trial.

February 12, 2018

Top 10 books about the Scottish Highlands and Islands

I could resist posting this – by Kerry Andrew from the Guardian, 07/10/18.

I’ve been obsessed with the Scottish Highlands and Islands since first going there on a family holiday at the age of 10. Its remote, rugged landscape has pulled me back most years since, whether to stay in the remote Moor of Rannoch hotel – where the nearest village is 13 miles away – or camping in Glen Coe and Glen Nevis .

To me, it’s the most beautiful place on Earth, but to ignore its raw, forbidding nature would be wrong. It’s a real place, and real people live there. My novel, Swansong, throws a 20-year-old English student into a disquieting world; it draws on a West Highlands version of a folk ballad, but is as much inspired by the real people I’ve encountered there as by the jaw-dropping scenery and often endless rain.

In fact and fiction, these books shine different lights on Scotland’s distant north.

1. The Crow Road by Iain Banks

With one of the best opening lines of any novel (“It was the day my grandmother exploded”), Iain Banks’s book follows a large, eccentric family, the McHoans, as the slightly feckless student Prentice plays detective within his own family to explain the disappearance of his uncle Rory. Set mostly in the West Highlands in the early 90s, there are plenty of familiar tropes here – whisky, ceilidhs, Uncle Fergus’s huge country pile – but just as many idiosyncrasies, from the looming Gulf war to the Cocteau Twins, a struggle between religion and atheism, and a massive, cement installation on the Isle of Jura. It’s a warm, witty and ultimately very poignant book.

2. The Outrun by Amy Liptrot

An impressive debut memoir by the Orcadian Amy Liptrot, who unflinchingly details a decade of addiction in London and her move back home to recover. It is not an easy retreat. The “outrun” is the name of the rough pastureland on her parents’ farm, a place on the edge of things. The islands are windswept and bleak, and it’s often achingly lonely – she ends up moving to the tiny island of Papa Westray to monitor corncrakes – but the landscape works its way in. The environment is deftly sketched, from the winter moons to greylag geese and a night-snorkelling excursion. There’s huge vulnerability here, answered by Liptrot’s bloody-mindedness and Orkney’s magic.

3. Corrag by Susan Fletcher

A historical novel set around the Glencoe massacre of 1692, in which three dozen members of the MacDonald clan were brutally slaughtered by William III’s redcoats. It is told from the perspective of Corrag, a young woman regarded as a witch who is incarcerated in Inveraray after the event, and by the Jacobite priest who is sent to interview her. Fletcher’s prose is shimmering, particularly when she writes about Corrag’s relationship with the natural world.

4. Girl Meets Boy by Ali Smith

A typical book by one of our wonderfully atypical writers, full of her usual play of language and her treatment of profound subjects with the lightest and most dazzling of touches. It transposes the myth of Iphis from Ovid’s Metamorphoses to modern-day Inverness, takes ecology, consumerism and gender fluidity along for the ride, and is (spoiler alert) a gay love story with a happy ending.

5. A Last Wild Place by Mike Tomkies

Mike Tomkies left his job as a Hollywood journalist to build his own cabin in Canada, before coming to the West Highlands and writing nine books about living among its wildlife. This, his best-known book, details a year in Wildernesse, his home by Loch Shiel. The house was accessible only by boat or on foot, and there he lived, off-grid, in the company of his alsatian, Moobli. Perhaps not the most lyrical example of nature writing, it is nonetheless a gripping account of the dramatically shifting seasons spent close to golden eagles, pine martens and wildcats – and is as much about his own struggle for survival as those of the creatures he observes.

6. Under the Skin by Michel Faber

This dark, eerie novel is set in the bleak north-east of Scotland, where humanoid alien Isserley cruises the A-roads looking for well-built, single male hitchhikers to drug and take back to her home planet. To go into the details of why would be to lessen the chilling and rather stomach-churning impact of the reading experience. It’s as much a satire on human consumption, business and the environment as it is a fist-in-mouth read.

7. Love of Country: A Hebridean Journey by Madeleine Bunting

Too often we think of Britain as a singular landmass, but we are the British Isles, Madeleine Bunting reminds us as she embarks on a search to understand some of our most distant outposts. It’s not an exhaustive journey but a closer look at a few of them, including Lewis, Iona and St Kilda. She captures the magnetism of these islands, how they have inspired some of our best-known culture – George Orwell, JM Barrie, Robert Louis Stevenson – and played an essential role in history and trade. It’s beautifully written, and as much about the people that have populated these wild places as the landscapes themselves.

8. An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Folk and Fairy Tales by Theresa Breslin and Kate Leiper

A sublime collection of folk stories, with water kelpies, selkies, fairy folk, brownies and brave wrens among the tales from the Highlands. (There are also several from the Borders.) Theresa Breslin’s pristine, sparkling retellings are accompanied by enchanting illustrations from Kate Leiper.

9. The Sopranos by Alan Warner

Most of Alan Warner’s books are set in “the Port”, a fictionalised version of his native Oban. Here, a vibrant bunch of teenage girls from the town, who possess both excellent singing voices and vividly ribald lives, cause merry havoc on a choir trip to Edinburgh. The convent schoolteachers are no match for their admirable drinking and shagging, and there is real heart at the centre of it all. It captures this age group brilliantly, from their wardrobes to their language.

10. Natural History in the Highlands and Islands by F Fraser Darling

A classic from 1947, part of the Collins New Naturalist Series. Philosopher-naturalist F Fraser Darling worked for most of his life in the West Highlands, and made deep studies of the behaviour of its red deer and grey seal populations. This is an intensive and ecologically minded study of the flora and fauna of the north of Scotland, with some beautifully evocative lists of vegetation, if you like that sort of thing. A good thing to have in your pocket on your next trip.

January 10, 2018

The First DI Henderson Audiobook!

The first audiobook to be released in the DI Henderson crime series is published today. The 5th novel to be released, Red Red Wine, is read by Scottish actor, Joshua Manning. I auditioned many narrators for the part, but only Josh captured the essence of the voice I had in my head. He also did a great job on all the other characters in the book: the Swedish ferry boss, Yorkshire-born DI Edwards and the London villains.

The audiobook is available on Amazon through their Audible subsidiary, but unfortunately price setting is out of my hands. If you sign up to Audible, which you can do on the Amazon website, the first audiobook you download is free.

You can find the audiobook and listen to a sample here:

December 8, 2017

Best Thrillers and Crime Books 2017

It’s that time of year again, the ‘Best Of’ season – why should crime fiction be any different? This is the Daily Telegraph’s take on the best thriller and crime books of 2017.

A Legacy of Spies by John le Carre. Peter Guillam, a former colleague of George Smiley has retired to Brittany when he receives a letter summoning him to London. Somebody must pay for the mistakes of the past, why not him? Classic Le Carre. Amazon review average 4.3.

Into the Water by Paula Hawkins. Jules’s sister Nel is found drowned in a body of water known locally as the Drowning Pool, but Jules knew she would never jump. The story is told from a dozen viewpoints which many readers found difficult to follow. It was always going to be a problem following up a phenomenal success like The Girl on the Train. Amazon review average 3.4.

The Dry by Jane Harper. Tensions rise as Australia suffers its worst drought for over a century, and they boil over when three members of the Hadler family are found murdered. Policeman Adam Falk returns to the town to attend the funeral of his boyhood friend, but they shared a hidden secret that threatens to bubble again to the surface. Amazon review average 4.5.

The Long Drop by Denise Mina. The author re-stages one of the Peter Manuel murders, crimes which terrorised Glasgow in the 1950s. Manuel was convicted of seven murders and hanged in 1958. The book is part-fiction, part-fact and takes you into the mind of a serial killer. Amazon review average 4.3.

He Said/She Said by Erin Kelly. Laura and Kit are keen followers of eclipses. They attend an eclipse festival in Cornwall where they witness a rape. As the story progresses, the author muddies the water at some points leaving you sympathetic for the victim and at others, sympathetic to the ‘protagonist.’ Amazon review average 4.1.

Spook Street by Mike Herron. Jackson Lamb is a pen pusher at Slough House, home of MI5. They are known as ‘slow horses’ former spies put out to pasture in the hope they will resign. Sparkling dialogue. Amazon review average 4.8.

Defectors by Joseph Canon. Simon Weeks, a New York publisher has the opportunity to publish the memoirs of his brother, a defector to the KGB. He can’t resist as he wants to know why his brother defected. A moody spy novel, recreating well the paranoia that pervaded Russia in the early 1960s. Amazon review average 3.8.

Traitor in the Family by Nicholas Searle. Bridget is married to Francis, an IRA terrorist and is expected to keep her mouth shut. On a mission to blow up an electricity sub-station, her husband is betrayed and sent to prison. Is this Bridget’s chance to escape? Francis is released under the Good Friday Agreement and seeks his betrayer, but will his search result in the death of both of them? Amazon review average 3.9.

The Spy’s Daughter by Adam Brookes. Disgraced spook, Philip Mangan gets a shot at redemption when he tries to help a teenage girl, a mathematical genius, evade the clutches of Chinese military intelligence. This completes the Mangan trilogy, a modern spy classic. Amazon review average 4.6.

You Don’t Know Me by Imran Mahood. The novel takes the form of a monologue delivered to a jury over 10 days by a young black man defending himself on a murder charge. Using street dialogue, it immerses the reader into London gang culture. Praised for its originality. Amazon review average 4.2.

Good Me, Bad Me by Ali Land. Annie’s mother is a serial killer and when she hands her over to the police, she hopes for a new start in life. With the trial looming, Annie will be forced to appear, but does she know more than she’s letting on? Amazon review average 4.3.

The Pictures by Guy Bolton. Set in 1930s Hollywood, it follows a morally dubious fixer as he tries to smooth over the suicide of a producer. A routine job proves anything but and forces the fixer into making a decision; should he do exactly as the studio wants, or follow his new resolve to go straight? Amazon review average 4.4.

Sirens by Jospeh Knox. Detective Aidan Waits is searching for a missing teenager, daughter of a Manchester politician. The book leads the reader on a gritty trawl through Manchester’s drug culture, and even Detective Waits isn’t averse to sampling some of their merchandise. Amazon review average 4.1.

October 24, 2017

What Inspired Me To Write Night of Fire?

When I finished reading Anne Cleeves’s book, Black Raven, it got me thinking. Why doesn’t the place where I live and set my DI Angus Henderson novels, Sussex, have a major celebration like Up Helly Aa? This is the annual Viking celebration on the Shetland Islands, a colourful parade through the streets of Lerwick and the ritual burning of a Viking boat on the shore. Such a large and public event would not only be a wonderful background for a novel, but it would also become one its main characters. Then it hit me. The annual Bonfire Night celebration in Lewes.

Guy Fawkes and his confederates, as every British schoolchild knows, tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605, in a plot to kill the protestant King James I and restore a Catholic monarchy. On the anniversary of the plot, 5th November, Britain celebrates this event with fireworks and bonfires, and hard to believe, this has been the case almost without a break since 1605. Nowhere is this celebrated with more exuberance than the Sussex town of Lewes.

Nestling under chalk cliffs, Lewes is an archetypal Sussex county town with grey stone buildings, narrow streets, an austere Victorian prison and the remains of a Norman castle. The town is nowhere near as brash as its westerly neighbour, Brighton, and doesn’t resemble a holiday resort for the elderly like its easterly neighbour, Eastbourne With a population of less than 20,000, it’s a minnow compared to its two flanking neighbours, but punches above its weight by housing the offices of East Sussex County Council and the headquarters of Sussex Police.

On the evening November 5th and in front of over 80,000 people, the town comes alive with music and a long procession of pirates, Civil War cavaliers, North American Indians to name a few, each carrying lighted torches, dragging tar barrels and pulling a cart containing an effigy. Standing four to five metres tall, the effigies are often based on well-known politicians with recent events providing no shortage of material. Popular choices have included the Pope, Sepp Blatter and Jeremy Clarkston. Guy Fawkes also makes an appearance and once the procession is over, he and the statesmen and any irritating television presenters, are placed on a bonfire and set alight to whoops of delight from a boisterous crowd.

The procession, the costumes and the construction of the effigies are the responsibility of seven Lewes Bonfire Societies, a tradition harking back to the 1850’s. Fiercely protective of their identities and ideas, there is little interaction between them as all seven try to outdo the others by putting on the best show of the night.

When I first attended the celebrations, it wasn’t long since I’d moved to Sussex from Glasgow, a city where religious bigotry was prevalent, as epitomised by the city’s top football teams. At the ritual burning of the effigies at Lewes, I was astonished to hear condemnations of the Pope and Catholicism, but soon realised the revellers were merely mimicking the prejudices of 17th century England, and not trying to incite religion hatred among their audience. At least at that late hour of the evening, it is hoped the children who lined the streets to cheer the Bonfire Societies walking past are now safely tucked up in bed.

Read a synopsis of Night of Fire by clicking the Home page on this website.

September 12, 2017

New Book!

Yes, the new book is out!

Called Night of Fire it is now available to pre-order until 5th October when it will be published in Kindle and paperback.

Here’s a short preview:

The Bonfire Night procession moving slowly down Lewes High Street in Sussex is being watched by thousands of onlookers. DI Henderson is in the crowd, but he can’t shake from his mind the murder of a Bonfire Society member days earlier when he was found burned to death.

With most of the evidence destroyed by fire, the DI is forced to trawl through the victim’s life, looking for clues. A former friend, Guy Barton, soon comes to the fore, as not only was he involved in a fight with the victim, the victim was also having an affair with his wife.

With no conviction in sight, the case is about to be shelved when new evidence is unearthed. It leads Henderson to the real culprit, but pushes him and DS Walters into the gun sights of a deranged killer.

To find out more and to buy, click on the link: