Leiah Moser's Blog, page 5

November 1, 2017

Why No Jewish Narnia?

So way back in the day, when I was still living in Tulsa, OK and had maybe just converted to Judaism, my rabbi handed me a copy of the (then relatively new) Jewish Review of Books. In this particular issue was an article by Michael Weingrad entitled “Why There Is No Jewish Narnia.” I read it. It bothered me. It still does.

This article is not without its issues. At the very least Weingrad’s understanding of Fantasy seems overly reductionist, placing undue emphasis on romantic nostalgia for a vanished feudal past as a central and essential element of the genre. But while it might be a useful exercise for a later time, I’m not here today to critique the article itself, because it’s not really the article itself that I take issue with.

It’s the title.

When I read the article all those years ago, I initially misread the title. Rather than “Why There Is No Jewish Narnia,” I thought it said “Why Is There No Jewish Narnia?” A subtle difference, but an important one, because it underscores how Weingrad approaches the question as if it were already answered, as though taking it for granted that there are good reasons why Jewish culture has produced so few notable works of fantasy. That’s what bothers me.

Underlying all of this is a set of assumptions about what Judaism is and what it can be, a set of assumptions that were outdated and inaccurate back in the 60’s and 70’s and which continue to be so to this day – that Judaism is “this-worldly” rather than “other-worldly,” that it is somehow more inherently rationalistic than Christianity, that elements of magic, the supernatural, and above all mythology are foreign to it. The fact is that these elements of Jewish self-understanding are ultimately derived from the 19th-century Wissenschaft des Judentums movement, representative of the efforts of members of the newly-formed class of German Jewish academics to cast Judaism in a light that would be more palatable to the rationalistic mainstream German academic culture. In pursuit of this goal, historians like Heinrich Graetz cast the history of Judaism a particular light, downplaying the deep importance of mysticism and mythology to the development of Judaism as a religion. The fact that Hasidic Judaism, grounded in a version of medieval kabbalah radically reformulated to be accessible to the masses, was developing in eastern Europe into one of the most successful religious movements in Jewish history, was apparently too insignificant to have been worth their notice.

Today, despite the work of such noteworthy researchers into the field of Jewish mysticism as Gershom Sholem and Moshe Idel, the idea of Judaism as an essentially rationalistic and “this-worldly” faith is still with us. But this way of looking at ourselves seems deeply limiting to me. It strikes me as ignoring not only a fundamental aspect of the history of our civilization, but of our own spiritual being. In order to be a healthier, more complete people, I think we need to come to terms with the mystical side of ourselves, and of our religion, which to this day still tends to be ignored. I also happen to think that the most powerful way of exploring this less-than-adequately-acknowledged side of Judaism may be through the medium of fantasy fiction.

I’ve thought about Weingrad’s article from time to time over the years, and more than once I’ve wondered why it bothers me so much. I think at last I may have an answer – because in reality the title doesn’t strike me as a bare statement, nor as a question calling out for scholarly inquiry. To me, it feels much more personal than that. It feels like a challenge. In that light, the answer to the question, “Why is there no Jewish Narnia?” seems laughably simple.

It is because I haven’t finished writing it yet.

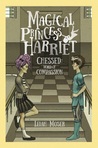

Next post: Introducing Magical Princess Harriet

October 18, 2017

Podcast!

I had the honor of being featured in the inaugural episode of #trending Jewish, a new podcast being put out by the Reconstructionist movement. I had a great time recording this with Bryan and Rachel. In the episode we talk about the importance of Talmud as a source of inspiration for rethinking Jewish life in the 21st century, the union of analysis and emotion, and the potential of using electronic music in a liturgical context. Plus, a few tunes by yours truly! I’d highly recommend giving it a listen.

October 8, 2017

Back Again (and a prayer for Sukkot)

Well, once again it has been quite a while since I posted anything here. A lot has happened in the last two years, to be sure – graduated, became a rabbi, got married… I’m a step-parent now. For real. But there will be time enough to hash all that out. For now, this is what I have to say: For those of you out there who actually read this thing, I apologize for letting it languish for so long. Due to one thing and another, for a long time I wasn’t certain that I actually had anything to say. Now, I’ve decided that I do. So stay tuned, I guess. In the meantime, here’s what I’ve been praying this year for Sukkot:

Beloved God, often are you praised as the one who settled our wandering ancestors in the land of your promise, but how often do we praise you for commanding Abraham and Sarai to abandon house and home for a life of wandering? Often are you praised as the maker of peace; how often do we praise you as the one who unsettles the mind and brings disquiet to the heart? Contentment, security, comfort – we crave these things above all else, and so we beg you for them when we don’t have them and praise you for them when we do. And yet, what is it that you ask of us? To “go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” (Genesis 12:1)

In our generation many of us have only a tenuous connection to the soil, and so it may seem paradoxical to us that this the season of harvest rejoicing was also for our ancestors the time of deepest anxiety. Giving thanks for the sustaining bounty of the earth, they also prayed like hell for the life giving rains that might or might not come this year. This then was the essence of your promise – to take us out of slavery in a land of security watered by the never-ceasing Nile and to grant us freedom in a land whose rocky heights are forever dependent on the rains of heaven. So goes the psalm:

Place not your trust in human benefactors

In human beings without power to save

Their spirit leaves, they go back to the ground

On that day their plans are lost

Happy is the one with the God of Jacob for a help

Whose hope is in the Lord our God

Dear one, you know what we are like. In unsettled times it is hard for us not to dig in, to retrench, to close the gates and bar the doors and wait for the storm to pass regardless of who might knock without, looking for shelter. This, we know, is the way of humanity, but it is not your way, and so you command us at this time of year to leave the security of our homes, to camp out in temporary shelters like the refugees we are and were and ever will be, to welcome in every guest.

And so, in this the season of our insecurity, we pray to you not for comfort, but for clarity; not for complacency, but for compassion; not, above all else, for security, but for the disquiet of the heart that drives us out into the world to do your work.