L.P. Ring's Blog, page 5

December 30, 2018

My Year of Good Reads

Closing in on the end of the indiscriminately determined 12 month period that was 2018 leads many of us to review what we’ve accomplished, what we came close to reaching, and that gym membership that we only used a half a dozen times after our January detox. One goal I set myself for the past year was to read a certain number of books.

Knowing myself well-enough to realise that I needed some form of counting system to keep me on track, I joined https://www.goodreads.com/ . I set myself the modest total of 26 books to read, did what I assumed was the done thing of adding a load of books I’d already read, and chose a book to start with – Neil Gaiman’s ‘American Gods’. I’m the kind of person who likes to have a few books for different moods, locations and social occasions (yes, I occasionally read at social occasions, the same way a lot of other people conduct microscopic examinations of their social media at meal times) so James Church’s ‘Corpse in the Koryo’ went up there too. Then I was set. Eleven months of reading awaited as I started on February 10 – either as I’m not beholding to the Gregorian calendar or because I am really unorganised in Januaries. You decide.

As the months galloped by, I utilised my Kindle, books I’d bought to read but still hadn’t, the Wellington City library and Unity Bookstore for suitable tomes. Being an aspiring crime writer, I obviously had my fair share of modern works and classics in that genre to read including Lee Child, Pierre Lemaitre, Ragnar Jonasson, Eric Ambler, Georges Simenon and Ross MacDonald. I boned up on my Hammett, discovered how James Ellroy is even better in print than at the movies, added to my knowledge of the wonderful James Sallis and dodged hard time with Edward Bunker. I tried to branch out beyond genre fiction as well by reading James Baldwin, Anais Nin, Norman Mailer, Christopher Isherwood, Margaret Atwood. I re-read and re-appreciated Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’. I decided to find out more about Ishmael by starting the one about the whale. And I quickly went beyond my target of 26. Upwards to thirty, to forty, to fifty. I posted the GoodReads review I wrote for Neverworld Wake by Marisha Pessl (my number 51). Finally, today, I hit 53 and 204% of my target for the year.

So how do I feel? Kind of dis-satisfied, truth be told. Maybe it’s me. Maybe my niche as a genre fiction devotee has put me against anything over 300 pages. Maybe it’s the world we now live in full of work and dinners with friends, cinemas and Netflix. Starting with ‘American Gods’ felt like a statement of intent. Go after the big boys, the longer works. Maybe I thought one of the 26 might be David Foster Wallace’s ‘Infinite Jest’ or Thomas Mann’s ‘The Magic Mountain’. But what actually happened was, subconsciously at first, but then extremely consciously, I started looking at the book total instead of focusing on the pages. Are five books of 200 pages each as valuable as one work clocking in at one thousand? They are if you are counting spines. Roberto Bolano’s ‘Monsieur Pain’ is certainly an interesting read, but it is 122 pages. And although I had bought and settled it on my bookshelf long before I set up my GoodReads account, it felt like cheating.

And I never did find out what happened to Ishmael as my progress counter for ‘Moby Dick’ stands at 35%. Although I have at least met the monster.

So the New Year arrives in a few hours and I have to decide on a new total. ‘The Magic Mountain’ and ‘Infinite Jest’ are both still a few yards away from where I’m typing. Settled within arms reach, however, is Graham Greene’s sharply insightful but slight on word count ‘The Quiet American’. I truly believe that from a quality perspective, I’ve read broadly, intently and well in 2018. But when GoodReads asks me for my target tomorrow, I’m going to take a little time before deciding on that number, with memories of last year’s total chasing running through my head. Maybe my bedside locker should have something with a bit more heft on it. Maybe I’ll take care of that right now.

A Good Read’s Year

[image error]Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

Closing in on the end of the indiscriminately determined 12 month period that was 2018 leads many of us to review what we’ve accomplished, what we came close to reaching, and that gym membership that we only used a half a dozen times after our January detox. One goal I set myself for the past year was to read a certain number of books.

Knowing myself well-enough to realise that I needed some form of counting system to keep me on track, I joined https://www.goodreads.com/ . I set myself the modest total of 26 books to read, did what I assumed was the done thing of adding a load of books I’d already read, and chose a book to start with – Neil Gaiman’s ‘American Gods’. I’m the kind of person who likes to have a few books for different moods, locations and social occasions (yes, I occasionally read at social occasions, the same way a lot of other people conduct microscopic examinations of their social media at meal times) so James Church’s ‘Corpse in the Koryo’ went up there too. Then I was set. Eleven months of reading awaited as I started on February 10 – either as I’m not beholding to the Gregorian calendar or because I am really unorganised in Januaries. You decide.

As the months galloped by, I utilised my Kindle, books I’d bought to read but still hadn’t, the Wellington City library and Unity Bookstore for suitable tomes. Being an aspiring crime writer, I obviously had my fair share of modern works and classics in that genre to read including Lee Child, Pierre Lemaitre, Ragnar Jonasson, Eric Ambler, Georges Simenon and Ross MacDonald. I boned up on my Hammett, discovered how James Ellroy is even better in print than at the movies, added to my knowledge of the wonderful James Sallis and dodged hard time with Edward Bunker. I tried to branch out beyond genre fiction as well by reading James Baldwin, Anais Nin, Norman Mailer, Christopher Isherwood, Margaret Atwood. I re-read and re-appreciated Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’. I decided to find out more about Ishmael by starting the one about the whale. And I quickly went beyond my target of 26. Upwards to thirty, to forty, to fifty. I posted the GoodReads review I wrote for Neverworld Wake by Marisha Pessl (my number 51). Finally, today, I hit 53 and 204% of my target for the year.

So how do I feel? Kind of dis-satisfied, truth be told. Maybe it’s me. Maybe my niche as a genre fiction devotee has put me against anything over 300 pages. Maybe it’s the world we now live in full of work and dinners with friends, cinemas and Netflix. Starting with ‘American Gods’ felt like a statement of intent. Go after the big boys, the longer works. Maybe I thought one of the 26 might be David Foster Wallace’s ‘Infinite Jest’ or Thomas Mann’s ‘The Magic Mountain’. But what actually happened was, subconsciously at first, but then extremely consciously, I started looking at the book total instead of focusing on the pages. Are five books of 200 pages each as valuable as one work clocking in at one thousand? They are if you are counting spines. Roberto Bolano’s ‘Monsieur Pain’ is certainly an interesting read, but it is 122 pages. And although I had bought and settled it on my bookshelf long before I set up my GoodReads account, it felt like cheating.

And I never did find out what happened to Ishmael as my progress counter for ‘Moby Dick’ stands at 35%. Although I have at least met the monster.

So the New Year arrives in a few hours and I have to decide on a new total. ‘The Magic Mountain’ and ‘Infinite Jest’ are both still a few yards away from where I’m typing. Settled within arms reach, however, is Graham Greene’s sharply insightful but slight on word count ‘The Quiet American’. I truly believe that from a quality perspective, I’ve read broadly, intently and well in 2018. But when GoodReads asks me for my target tomorrow, I’m going to take a little time before deciding on that number, with memories of last year’s total chasing running through my head. Maybe my bedside locker should have something with a bit more heft on it. Maybe I’ll take care of that right now.

November 3, 2018

Ross MacDonald’s Ethical Sleuth

[image error]

‘I don’t know what justice is… truth interests me, though.’

Making his first full novel appearance in 1949’s The Moving Target, Lew Archer perhaps best of all epitomised the old Raymond Chandler edict that detective stories feature the ‘plausible actions of plausible people in plausible situations’. Perhaps Chandler’s is not the most inspiring or lyrical of mantras, but it was a call to display characters warts and all that would have found plenty of credence in Ross MacDonald’s California-set crime novels. Over a series of 18 books, former police officer Archer often walks a thin line: beaten and imprisoned by crooks, barely tolerated by the police, maligned by the people he is seeking to help. But he has a commitment to truth, and will often see that truth out even if it’s to his detriment. Archer’s code is about discovering what is right, doing as much as he can to set it so, but ultimately allowing people to live their own way. Even in ensuring that benefit comes to those that are deserving but completely ill-equipped to use such advantages wisely. In that, he is a far more understanding and empathetic character than either Hammett’s Continental Operative or Chandler’s Philip Marlowe.

Archer’s world encapsulates everything from the filthy rich to the destitute of street corner hustlers and trailer park trash. The corruption he sees is often based in the very foundations of how the rich acquired their wealth – inherited money and land or latterly oil often a key ingredient in MacDonald’s plots even from the environmentally unconscious 1950s. The difference between the rich and poor in Archer’s world is so often a case of luck, with invariably a tragic flaw in either the make-up of an individual or the family background contributing to what will be – without Archer’s assistance – an inevitable fall. By the time the case is over, while some balances may have been achieved, the reader will know as well as Archer himself that trouble is still just around the corner. The world has been righted as far as Archer can, and almost like Alan Ladd’s iconic Shane, he will walk away and allow those remaining to do what they can for themselves.

Throughout his books, MacDonald regularly made use of his literary background as only a graduate student who had immersed himself in the works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge could have. Lauded at the time by such luminaries as William Goldman and Eudora Welty, MacDonald continues to have a dedicated fan-base on both sides of the pond, influencing the works of James Ellroy, Jonathan Kellerman and Michael Connelly in the States while the Irish writer John Banville sees MacDonald as an artist capable of ‘ingenuity and subtlety’. The Archer novels also offer a telling glimpse of a California changing rapidly even as society becomes more stratified. The richer will remain so irrespective of their faults, the poor will continue to struggle whether in the presidency of Harry Truman or Gerald Ford. Archer will watch all this with as unjaundiced an eye as possible, a man who has a ‘private conscience; a poor thing but (his) own’.

Check out: The Drowning Pool, The Galton Case, The Ivory Grin, Sleeping Beauty.

September 30, 2018

The True Detective

[image error]

From Edgar Allen Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin and Wilkie Collins’s Sergeant Cuff through Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot, the typical detective was known for observation and careful thinking, utilising arcane knowledge and ‘little grey cells’ to catch the criminal and set everything to rights. By the 1930s, the Golden Age of detective fiction had not only brought us Christie’s Poirot, but also the gentleman detective Lord Peter Wimsey (Sayers), Ngaio Marsh’s Inspector Roderick Alleyn and a slew of other (both amateur and professional) detectives. Across the pond though, in a far tougher, more urbanised and less privileged world, a different type of detective was knocking heads, dodging bullets and chatting up dames. And the progenitor of these was a World War One veteran who had left school at 13.

Creator of The Continental Operative and Sam Spade, Samuel Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961) was writing short fiction before he hit 30. Farming his own experiences – both good and ill – as a Pinkerton’s detective for inspiration, his hard-boiled crime stories for pulp publications such as Black Mask were the template on which later detectives like Philip Marlowe (Raymond Chandler and Lew Archer (Ross MacDonald) were based.

The Continental Op, making his first appearance in 1923, was unnamed, often working alone or as the leader of a small group of detectives, and answerable to a callous, hard-headed boss referred to as ‘the Old Man’. Collecting a set of short stories based around the fictional town of ‘Poisonville’, Hammett’s first novel – 1929’s Red Harvest – has the Op enter a world where worker’s rights and liberty mean nothing before big business and money. The Op is hired by a local industrialist to clean up a city riven by different criminal gangs that had originally been invited to the town by the industrialist himself to break up a union strike. Hammett’s sympathies – ones which would later get him into trouble in McCarthyite America – for the workers of the city are clear, and the novel has often been compared in plot to work like Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo.

Sam Spade made his first appearance in the iconic hard-boiled novel The Maltese Falcon before appearing in a few later short stories. Told in third person as opposed to the first person narrative of the Continental Operative novels and stories, Spade is more the idea of what detectives want to be – tough, streetwise, fearless lady-killers – than what they actually are. Both the Continental Op and Sam Spade are hard men, men of action who are more at home with criminals, gangster’s molls and other low-lives. But the Op seems set to do the right thing where he can – for workers as much as heiresses – and is a lot closer morally to the man Hammett himself probably was as a detective.

With Hammett following the maxim of offering relatively little by way of physical description, what the Op looked like was generally left to the reader’s imagination. The Dain Curse suggests to us a man who has little left, now far away from any youthfulness and perhaps closer to a physical, unfeeling shell than what he wants to be. Life has slipped through his fingers. What’s left is “a monster without any human foolishness”, someone who can play both gangsters and corrupt cops off each other, but still have enough goodness in him to save an heiress and help ween her off a morphine addiction.

While the Continental Operative was the character Hammett turned to most in his writing, it’s Sam Spade who is most remembered – primarily for the portrayal of Humphrey Bogart as the wise-cracking detective. Later in life Hammett found his communist sympathies put under the microscope and was jailed for contempt of court after he refused to name names.

Inspiration eluded him as he got older and his health began to fail, and the volume of work he created in the 1920s and early 30s was never reached again. However, in the Op and Spade characters were the seeds from which Chandler, Spillane and MacDonald created the hard-boiled style of detective who populated so many film noir from the 1930s. But in Hammett’s world, the Continental Op was a man who fought for what was right, fought for the underdog, but was often alone in the world. The American answer to The Golden Age of crime is heavily populated with gun-totting wise guys, but in many ways Hammett created the fairest of them.

September 16, 2018

Five Writing Inspirations

[image error]

The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

Philip Marlowe is called to the wealthy General Sternwood’s home to help with sorting out a blackmailer. This simple opening leads the private detective through a labyrinthine plot involving pornography, gambling and murder in Los Angeles, with Marlowe battling gangsters, jealous lovers , and avoiding cops who seem bent on getting his licence from him. It also brings him closer to not only Sternwood but also the General’s two daughters – the clinical, calculating Vivian and the wild, unpredictable Carmen.

Chandler’s hero (or anti-hero) is the perfect template for the Noir detective – not dirty enough to give into temptation, but also battling against authority. The writer’s focus on style and atmosphere brought us one of the greatest detectives of all time in Philip Marlowe along with a 1930s version of the Tarantino puzzler ‘Who killed Nice Guy Eddie?’ in ‘Who killed General Sternwood’s chauffeur’? But it isn’t even as much about the plot – although the denouement is typically satisfying – as it is the protagonist and the tawdry universe that he inhabits; he’s never a villain, but not clean enough to be one of the angels.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

Richard Papen is even more an outsider than any noir detective. Where the detective is a loner by choice, Richard craves friendship and to be part of something. Where the detective is full of wisecracks and confidence, Richard struggles to have even normal conversations and is almost constantly excluded. He can’t fit in at school, is a disappointment to his father at home and initially struggles in the cloistered world of the upper-class Vermont College to which he’s escaped.

This lonely narrator thrills at being brought into the social circle of the Classics professor Julian Morrow and his ephemeral, other-worldly students. Yet he never seems that more accepted by the group than the much reviled and intellectually inferior Bunny Corcoran. With nods to Greek Tragedy and Fredrich Nietzsche, there are also echoes of the murderers Leopold and Leob’s obsession with the perfect murder. Tartt’s story has the narrator Richard tell us the ‘what’ within the first pages. It’s the ‘why’ – and that oh-so terrible conclusion – that are so important.

Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World by Haruki Murakami

Told in two divergent universes, Hard-boiled Wonderland’s narrator is a carrier and encryptor of information who finds himself helping an ageing scientist experimenting with sound removal devices in a laboratory hidden beneath Tokyo. At the same time, the narrator of ‘The End of the World’ finds himself trying to get permission to remain in a city. This means giving up on his shadow, which is cut away from him and banished to an area outside the city.

The focus switches between chapters with the narrator in ‘Hard-boiled’ encountering a selection of femme fatales, old authority figures and two thugs named Junior and Big Boy that wouldn’t be out of place in any pulp thriller. At the same time, ‘The End of the World’ is a dream-like world with the narrator existing in a walled-in city and jumping to the tune of the Gatekeeper. Between these two worlds, the central character(s) must find a way to survive, with the clock ticking inexorably towards his demise. Part, noir, part cyber-punk, part fantasy, Murakami’s 1985 novel wears its influences on its sleeve, with favourites like Raymond Chandler and William Gibson front and centre.

The Redbreast by Jo Nesbo

Nesbo’s Harry Hole series of novels has become hugely successful in recent years with the hard-living, harder-working misanthrope battling his way through a range of cases, corrupt fellow cops and unsympathetic authority figures. The Redbreast was the first book by Nesbo that I read but the plot – where Harry has to work a case with its roots back in Norway’s involvement in World War II – really spoke to me. The comparison between modern day neo-Nazis and people from Norway’s past who were sympathetic to the German cause not only hits upon my interest in history, but also on how some political groups will take any opportunity to spread discord. Add in an interesting sub-plot about police corruption and a possible political assassination and you’ve got a stirring mix of mayhem and murder to keep the readers as on-their-toes as Hole himself .

And one non-fiction:

On Writing by Stephen King

I remember discovering that an acquaintance of mine (later good friend) was interested in writing. We chatted for a few minutes about different authors, stuff we were interested in, and then he leaned in and asked me – ‘So, have you read Stephen King’s On Writing?’ King is one of the undisputed masters of genre fiction; his story of making the luxury purchase of a hairdryer for his wife once he sold the paperback rights to Carrie has gone down in writing folklore, but the part-autobiography / part writing manual is one of the first books any aspiring writer can read.

The road to hell may not exactly be paved with adverbs, but there is a lot of golden advice as well as some heartening stories in here as King describes the battles he went through to make it a published author. Then there is the advice. Read a lot. Write a lot. Don’t overdo the descriptions. I’ve bought a ton of writing books over the years, many with nuggets of wisdom in them, but none that offers as much as King’s memoir does.

September 1, 2018

Does (your book) size matter?

[image error]

“Call me Ishmael” is one of the most famous opening lines in American literature. The protagonist, a green hand newly hired as a seaman on the Whaler Pequod, finds himself on board a vessel captained by the monomaniacal Captain Ahab – a man recently crippled by a notorious white whale that goes by the name Moby-Dick. The novel was published in 1851 to decidedly mixed reviews, and at a dollar-fifty for a bound edition – there was also a three-volume edition available – (about U.S. $37 in today’s money) it was a price most shoppers could ill-afford. That it would go onto become one of the most feted novels in American fiction would be a fact probably both gratifying and surprising to its author Herman Melville, who only saw a few thousand copies sold in his lifetime and had been largely forgotten as a writer when he died in 1891.

Moby Dick is not an easy read either in volume or in style. Weighing in at about 600 pages (still less than The Brothers Karamazov or War and Peace), the book delves into such issues as religion in society, the existence of class in America, and multiculturalism of the sea-faring community among other things. It devotes chapters to describing different places and people, long sections to explain the different aspects of sailing, even a chapter on the different types of whales that the Pequod’s crew might hunt.

We are near a quarter in before we meet the antagonistic Captain Ahab, find out his goal for the voyage. It is – bar an ominous warning by a former seaman – the first time the reader gets any real feel for what action is ahead. Add to these considerations the near poetic prose, stylistic flourishes and the well-crafted symbolism and the reader is left with a lot to unpack.

It’s well-worth the effort, and yet. Melville had already had successful publishing experiences with other sea-faring adventures and would have hoped to have done financially well from a novel which took him 18 months to write. Such structure and devices would not, he would have hoped, have stopped the typical reader of his era from enjoying his work. But nowadays, what authors – particularly self-published ones – could expect widespread sales from such a complex work?

For every The Luminaries (just over eight hundred pages) or Infinite Jest (near a thousand with foot-notes) there are potentially hundreds of novels that will settle for somewhere around the 300 to 400-page mark. Among last year’s better / best sellers, literary fiction’s The Miniaturist and the latest Lee Child was just under four hundred pages. It isn’t just a question of how much the writer can produce (and how effective the narrative can run), but also how much attention and time a reader can pay to a book.

With self-publishing, that is even more the case. Romance has long been recognised as the top genre in e-books, with self-publishing super-star H.M. Ward’s first novel Damaged weighed in at around 340 pages before the sequel reached three hundred and twenty. From there, she started the hugely successful Ferro Family series where the typical novel doesn’t break two hundred.

This certainly isn’t the case with all authors – fellow romance titan Barbara Freethy continues to hit at around the 300-page mark – but writing shorter, leaner releases does seem to be the way to go. Turn to my preferred genre – crime and police procedurals – and the three hundred number or under comes up again. J.F. Penn of the Creative Penn website specialises in shorter, fast action books at an affordable price while much-hyped newcomer Matthew Farrell’s debut What Have You Done just makes the three hundred pages again.

So is shorter better? For self-published writers with a day-job there is definitely a limit to how much we can put into a book. Pages spent on characterisation, scene description and the minutiae of the world our characters live in are things our readership might only have limited time and patience for. However, in an era where the post-500 page novel is dropping out of sight, markets and tastes might be a great opportunity for authors. The market itself could be said to be creating tastes, and the tastes are at the moment for shorter, sharper fiction.

In addition, websites like Good Reads almost make reading a competition with yourself, where you can say you’ll read a number of books at the start of the year and see if you can make that number. This makes novels like Roberto Bolano’s Monsieur Pain at only 140 pages an opportunity for a quick-read as well as an opportunity to show off your knowledge of South American authors. And you’ll still have time for the latest dramas on Netflix or to watch the latest instalment of the Marvel Universe.

We might just have to put those nineteenth century classics aside for now. But for our own writing, we might also think carefully about how much time we can put into our own works. Not to mention, how much money we will charge for them.

August 23, 2018

Oh Mandy: Panos Cosmatos’s sophomore feature is an Evil Dead for the new millennium. But it’s also so much more.

[image error]

Red Miller (Nicolas Cage) and Mandy Bloom (Andrea Riseborough) are living a quiet, hermit-like wilderness existence in 1983 rural America. He cuts down trees, glowers intently and knocks back any attempts at friendship from his colleagues. All he wants to do in a typical evening is get home, watch some TV, eat some food and curl up in bed with his girlfriend where they can talk about each other’s favourite planet. She reads fantasy novels, labours over illustrations and helps make ends meet by tending counter at a local shop.

These are two people – both clearly damaged – who are happy as they are and don’t want anyone else disturbing their left-of-field yet idyllic existence. So when Mandy catches the eye of Charles Manson wannabe and ‘Jesus freak’ Jeremiah Sand (Linus Roache), the only real certainty is that their tranquil lives are set for utter destruction. Sand, supremely confident and utterly convinced that only adding Mandy to his tribe can complete him, sets his chief acolyte the task of kidnapping her. When she turns down his advances – giggling at both his musical ability and his manhood – Sand turns crazy, taking his fury out on the pair. Idyllic existence shattered, the bereft Red has nothing left to do but take revenge on those who have destroyed his perfect world. We viewers are set for an hour of near relentless action.

Nicolas Cage isn’t often the man to call if looking for subtlety. Thinking of his best work – Wild at Heart, Kick-ass, Face-off, Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant – the viewer encounters over-active, wild-eyed, kid on a jug of coffee type of performances. So when Panos Cosmatos wanted a chainsaw wielding, feral, vengeance-seeking mad-man as the focus of his second feature, Cage would have been near the top of his list. That Cage delivers completely on this is a sign that beneath all the jokes and memes (not the bees), Cage is one of the few actors out there who a director can truly depend upon to cut loose. The man is a bullet-proof legend, travelling from film-set to film-set in search of the perfectly tailored role. Often in recent years that role has proven elusive, but Mandy is the perfect film foil to show what can happen with a director encourages Cage to embrace all he can be.

The plot is relatively simple. Boy meets girl. Boy loses girl in a helter skelter-style attack on home and hearth. Boy goes on a vengeance-soaked rampage to punish those responsible. But amid that last hour of ultra-violence there is a scene told in flashback which details Red and Mandy’s first meeting. How she recognised something special in him and how he reacted to that knowing look on her face. It’s a near-perfect moment showing how Cage’s anchorless, seemingly-lost Red suddenly realises there is someone out there for him; there is a world for this taciturn emotionally-stunted American male beyond chugging down beers and nodding along to rock music in a bar. In scenes such as that, Mandy shows itself to be a lot more than just a gonzo violence-fueled rampage or exploitation homage like Hobo with a Shotgun or The Green Inferno. While there is an almost constant sense that this world is one drenched in a hypnotic, LSD-laced nightmare where real world logic and behaviour has no place, Cage and Riseborough’s relationship anchors the movie without allowing it to degenerate into Death Wish style shenanigans. Bruce Campbell once said in reference to Evil Dead that ‘Once the horror starts, don’t let it let up’ and once Red and Mandy’s world is attacked, the pace is largely kept fast and furious. But in a few vital scenes like that first meeting, there is an eye in the storm that allows us to see an extra depth to Cage’s Red. It’s in those moments that Cosmatos’s film really shows its heart, and shows why it should probably be on many critic’s film of the year lists.

August 9, 2018

Ryu Murakami’s Piercing hits the big screen with Nicolas Pesce’s ‘horror-comedy’ adaptation

Check into a hotel room, call an escort service that specialises in S&M, procure a call-girl and kill her. What could be simpler?

Picture a man standing over a crib. He’s staring down at the tiny, helpless occupant. But there’s something not quite right; he looks concerned, worried about something. Then you see the ice-pick in his hand. Just as start squirming at the possibility of where this will lead, a voice drags him from his thoughts. It’s his barely-awake wife, wanting to know what he’s doing.

Piercing the Ryu Murakami novel and the Nicolas Pesce film both begin in similar ways. Masayuki Kobayashi exists in mid-1990s Japan. Reed (Christopher Abbott) lives in some unknown American city at an undesignated time – though the lack of the more modern technological trappings of society keep us guessing as to its era. Both men have an itch they cannot scratch. Both men decide that the way to scratch that itch is to go to a nondescript down-town hotel, hire a call-girl – Chiaki / Jackie – from an S&M club, and stab her to death. It’s a bit of an extreme itch, but it’s either the baby or the call-girl.

Why isn’t it the wife? In Murakami’s novel, Masayuki’s wife is painted as a wholesome mother who has even managed to forge a career from home by offering baking lessons. Murakami takes his time over her description – her smell, her students, their first meeting in an art gallery and life together, the expensive baking table set up for her business . All this even though she’ll be barely heard of again once Masayuki manages to get a few days free-pass to walk on an assignment at the down-town hotel. This woman is a million miles from the prostitute-girlfriend that our stab-happy new friend finds himself increasingly remembering – the only time previously he indulged in his piqueristic fetish.

Little is shown of Reed’s wife. Her presence is simply to explain how Reed has ended up a father and seemingly well-domesticated norm who can’t just bring a prostitute home to butcher. Is Reed driven by a need to stab a specific type of woman or is his focus on a practitioner from S&M simply a means to an end – he can tie them up easily enough without betraying his true motives? That leaves us wondering if this is an obsession that must be quelled or a box-ticking exercise of a man not yet sure of what he wants. Whatever his triggers are – the film only makes a brief allusion to them later – they are what drives him to meet a girl like Jackie (Mia Wasikowska).

While the book explains in depth both Masayuki and Chiaki’s inner demons, these things manifest in the film without any initial explanation. Masayuki’s sufferings as a child and his (implied) follow-up toxic relationship with an older prostitute are pock-marked throughout the book’s narrative. Even the choice of an ice-pick is a nod to Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct, a film Kobayashi watches with his wife. No reference is made to this slightly bizarre weapon of choice in Pesce’s film. Perhaps it’s a symbol of the murkiness underlying Reed’s domestic existence? That’s for the audience to discuss.

Both Masayuki and Chiaki are the products of abusive homes – a topic explored in other Murakami works such as Audition. Where that book (alongside Takashi Miike’s film version) offers room for a feminist slant on the vengeful Asami’s treatment of the widower Aoyama and all the men who have betrayed her , the lack of any background on how Jackie has gotten to be a worker at an S&M club potentially robs us of that. Reed wants to murder a call-girl – preferably given his experiments with drugs – a helpless one. The necessarily fucked-up call-girl – with a fortuitous penchant for self-mutilation – is supplied. There is room here for a shift in the power dynamics, but the lack of a background for either individual leaves a hollowness in the film. Pesce may be trying to keep the protagonists on even terms by denying us access to either of their backgrounds, but he removes the impending sense of doom that Murakami ably shows; these runaway trains of dysfunctionality are barrelling towards each other, and we have a seat on the platform.

The indoor-setting allows a relatively painless geographical translation from Japan to America for Pesce’s adaptation – the globalisation of tastes mean cheap hotel rooms in one country are much like another. The time scale difference of two decades might be slightly more difficult to overcome for a modern audience. While Masayuki scribbles everything in a notebook, Reed’s decision to do so – although making a later plot point easier to explain – seems at odds in the 21st century. If you were planning a murder and dismemberment, would you keep the details in a notebook anyone could read? Pesce reduces modern mod-cons where he can to try and overcome this flaw. In an additional quirk, Like Tarantino with his grindhouse nods, Pesce makes a stylistic attempt with introduction credits that ape 1970s exploitation flicks and adds soundtrack flourishes such as music from Dario Argento’s 1982 horror Tenebre. Without explicitly stating this film isn’t set in the here-and-now, there are signals – almost knowing winks – there for the audience to pick up on.

Ultimately, Piercing the movie is one of those ‘close but no cigar’ moments where a director manages to change the scene of a work and even more or less work out the era differences but then screws about with the novel’s plot and time-line enough to spoil the experience. By emphasising the two-hander nature of the film, Pesce tries to focus everything on his protagonists, but these sacrifices are a pyrrhic victory – we will focus on Reed and Jackie because we have no other choice, not because we should. The source material keeps us focused on Masayuki and Chiaki because they are worth our squeamish fascination – the flashbacks to their appalling family lives add to this. Their pasts create a salaried worker who will obsess over what sound a slashed Achilles tendon might make and a call-girl who will muse over what drug dosage is necessary to incapacitate a man. But in offering us only a slither of Reed’s background (Jackie is seemingly just fucked up and in need of love), we can see a hint of how Reed will remain in his veritable hamster-wheel but not the reasons for it. That only leaves us with an inconsequential black comedy instead of a work that really tries to answer questions about who some of us are and why we do what we do. Not so much a case of lost in translation then, but more a case of left on the cutting room floor?

Ryu Murakami’s Piercing is translated by Ralph McCarthy and available from Penguin Books.

Nicolas Pesce’s Piercing was recently shown at the New Zealand International Film Festival.

August 3, 2018

Roger Corman’s lost classic The Intruder: As relevant now as in 1962

[image error]

In 1962, Roger Corman, after putting his own money in as part of the financing, started on a three-week shoot of the Charles Beaumont novel The Intruder in Missouri. The film, starred a young Canadian actor named William Shatner as the newly arrived troublemaker Adam Cramer who arrives by bus in the fictional town of Southern town of Caxton. It is a town at odds with the upcoming school de-segregation, with many unhappy at the idea of whites and blacks co-existing but unsure about what to do next. Cramer is a born opportunist and a man willing to stoke that dissatisfaction for his own personal gain. What will happen over the next few days will have massive consequences for many in the town.

The film is set just after the Little Rock Nine incident when soldiers were called to help African-American students enter the Central High School. Across the South, real-life populists and segregationists like George Wallace were coming to prominence, using the issue to reach disaffected voters willing to vote on one-issue. Indeed Wallace – elected Governor of Alabama for the first time in 1963 – would soon have his own ‘Little Rock’ moment trying to stop 3 African-American students from completing their enrolment at the University of Alabama (the event is referenced in Bob Dylan’s ‘The Times They Are a-changin’). He eventually stood down after an executive order from President John F. Kennedy. In addition, the Ku Klux Klan had seen a revival in numbers after almost having faded into insignificance in the 1940s. They would go so far as to bomb a church – killing four young girls – in 1963 in a crime that would go unpunished for a decade and a half. It was in the beginnings of this fevered and violent atmosphere that Corman took on Beaumont’s book – even casting the author in a minor role as the school’s principal.

Whether Cramer is truly a racist or not is difficult to say. He certainly says some shocking things in his speeches, although whether he’s just identified a niche where he can gain populist support – many now say the same of Wallace – is certainly a possibility. This is suggested when another guest at the hotel where he stays seems to see through him, referring to Cramer as not having a bad pitch and possessing technique – “we’re both selling something.” But does he really believe in the conspiracy theories about Russians and Jews that he spouts?

There’s a scene a third of the way through the film where Shatner gives a speech before the townsfolk. Emboldened by support from the wealthy and successful owner of the local paper, Shatner rails against segregation, calling it a communist plot and designed by the enemies of America – including naming a Supreme Court Justice (a Jew, Shatner intones) as aiding the plot. When he’s challenged on how he knows this, he refers to a shady-sounding organisation and name-checks Moscow funding. Of course, this was a time long before the internet and social media. A time when politicians had to be careful of falsehoods as they could be easily checked for accuracy and de-bunked later.

Cramer goes on to paint (what is for the towns-people) a frightening picture of a world in which they will be the underclass. In which they will be beholding to the minority. It’s a stylishly delivered speech and Shatner knows his crowd and how to reach them. Facts are nowhere near as important as the feelings he can inspire. Before the night is over, a family will be stopped and threatened by a mob while driving through the main street. This level of violence is acceptable to Cramer. Soon after, a church will be bombed and the preacher killed – in a tragic case of life echoing art in Birmingham, Alabama with the aforementioned killing of the girls only two years later. That shows that perhaps Cramer’s populist rabble-rousing has gone too far, but he doesn’t pay enough attention; he’s drunk on power and unwilling or unable to give it up. But the sheen of sweat on top of his brow and the hunted look in his eyes when he detects he’s losing control says enough of how far he is willing to go. How much does this man believe in his hate? Maybe only as far as it will get him.

Ultimately, Adam Cramer will be proven a coward – a man only interested in wielding power but unable to control the crowd he exhorts into rising at the first sign of a challenge – he also panics when a mob attacks a local newspaper editor, leaving the man blind in one eye. The tipping point comes when a lie threatens to bring consequences far out of his control, and faced with the truth of that lie, the townspeople melt away, leaving Cramer alone and friendless. What shouldn’t be forgotten, however, is that the towns-people are willing enough to follow Cramer and go far beyond his limits. In the end the truth was enough to quench their thirst for violence. Whereas then, at least in fiction, the truth seemed to ultimately matter to enough, a modern crowd might act differently. In these times, with other versions of Cramer, the truth seems to be both more pliable and to matter less than the side people are rooting for. For a crowd willing to operate on feelings above all else, the results can be far worse than anything seen in a movie theatre. Though the results can be seen on news channels clearly enough.

The Intruder struggled to find a distribution deal upon release and gradually faded into obscurity, for a long time holding the unwanted mantle of being the only Roger Corman directed film not to make a profit. However, Corman for years under-lined the importance of making a drama which refused to shy away from its tough subject matter, and Shatner gives one of his very best performances as the villainous Cramer. It’s shocking to hear the words coming out of Shatner’s mouth at times, perhaps even more so given how his later work make us see the man as a hero; he’s Captain Kirk, T.J. Hooker or the rascally lawyer Denny Crane, not a race-baiting cowardly hypocrite only out for his own glory and self-aggrandisement. For Shatner’s performance alone, The Intruder deserves to be watched. However, in times such as these, there is a lot more to consider than just Shatner’s performance as the villainous Cramer. In this film there are enough people to stand up for what is right, and few enough areas for others to hide in. But with the modern era having some even more Teflon than Cramer, the story The Intruder tells is, unfortunately, as relevant now as it was then.

Roger Corman’s The Intruder is available on DVD and on Netflix.

July 29, 2018

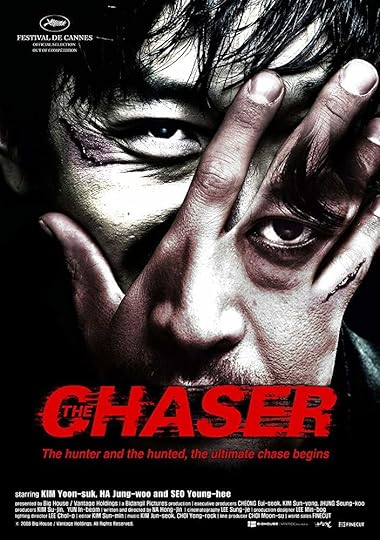

The Chaser (Chugyeokja) – a two-hour thrill ride that encapsulates the Korean police thriller

Director Na, Hong-jin’s debut feature showed the depth among Korean directors in the thriller genre. Park, Chan-wook’s Oldboy and Bong, Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder had already brought the Korean thriller into the spot-light, both highlighting the under-bellies of Korean society and the police’s inability to address issues in a society that to the outsider looks largely safe. Much like Bong’s afore-mentioned second feature, Na took inspiration for his film from a horrifying real-life case. Loosely based on the murderer Yoo, Young-chul’s crimes in Seoul a few years before, this 2008 film allowed Na and his co-writers to create a world in which police incompetence and hubris leaves little protection for those at risk. In a society where the lines between honesty and dishonesty are often blurred, someone refusing to follow kow-tow to society’s implicit rules can operate between those lines with little fear of being stopped.

Om Joong-ho (Kim Yoon-seok) is a disgraced cop turned pimp who is losing money and employees. Some of these women, he suspects, are running out on him for pastures greener, and it is something he wants stopped. Having sent one of his ‘girls’ to a job in the suburbs, he begins to suspect that perhaps this customer may be a rival pimp and decides to confront him. By the film’s end he has taken on the title role of the film – becoming the eponymous Chaser – as he seeks to track down a violent killer who preys on sex-workers and the elderly indiscriminately.

That a pimp could be a film’s hero says a lot about the world that the film portrays. While Kim, Yoon-seok plays it typically straight as a down-on-his-luck protagonist that really has good in him if it can be uncovered, villain Je Yeong-min (Ha Jung-woo) has no redeeming characteristics. From very early on it is clear that Kim’s pimp is out of his depth – his former colleagues don’t respect him any more than the few ‘girls’ he still protects. Against this he face against his will a vicious, gleeful force of nature who will destroy anything in his path. Many people say that the best villains are the ones who could have (i) gone good or bad – Michael B. Jordan in Black Panther or (ii) might even see themselves as a hero – Gene Hackman in Unforgiven. Ha’s killer is neither of these things. He sees the world as something to serve himself and luxuriates in every grinning act of violence he commits. This is an echo of the film’s inspiration – serial killer Yoo, Young-chul once said in answer to why he committed his crimes that “women shouldn’t be sluts, and the rich should know what they’ve done”. It’s a vicious railing against society’s ills that only seeks to trash at the surface for physical pleasures without actually pausing to wonder at root causes. It’s a characteristic which allows the director to construct a world where almost everyone is a villain and even daylight only brings a grey tint to proceedings.

The typical South Korean thriller motifs of useless cops, women being badly treated jostle alongside the chase itself. In addition, there is a nod to how rich and influential citizens are consistently protected to the detriment of others. In this film’s case the capital’s mayor requires so much protection (from protesters brandishing faeces) that the police aren’t able to investigate Je Young-min properly. He’s released even after admitting to killing nine people due to the lack of physical evidence – the police dismiss the character’s claims due his suspected mental health, another issue that is rarely addressed effectively in Korea. This is one of a few instances where critics point to contrivances that allow the film to continue, but the point made on mental health is a solid one. The real nub of why this happens may be in just how little some in Korean society think of the law enforcement officials of South Korea. Cops are almost always portrayed as either incompetent or weak, with a few mavericks – a possible nod to the ex-cop turned pimp – responsible for keeping society from dropping off the edge of a cliff into the East Sea. In a society where everyone is expected to conform, the maverick is both an inconvenience and the only one who can get things done.

If you can look beyond the occasional head-shaking piece of plot, The Chaser is one of the tautest, fastest thrillers to come out of South Korea in the last ten years. It certainly represented a fantastic calling card for director Na who has since brought us the crime drama The Yellow Sea and supernatural thriller The Wailing. For me, it also encapsulates why thrillers are among the very best genres out there for story-telling. Na can give us a fantastic, edge of the seat thrill-ride, allow Ha, Jong-woo to give a break-out, award-winning performance as the psychotic villain, and also reminding us of the problems that Korean society faces. For a debut feature it is a near tour-de-force.