Michael A. Stackpole's Blog, page 2

March 17, 2015

High Intensity Writing Workshop No. 6

Despite the fact that this will be one of the shorter exercises, it’s one of the most important you can use to develop characters and their unique voices. Previously I’ve had you work on dialogue so you could avoid the “he said” tags which make dialogues choppy. By the end of this exercise you’ll understand how to construct a character’s voice so well that there will seldom be any doubt who is speaking.

Dialogue consists of a number of a variety of components:

Vocabulary: The number of words you know is a function of age and education. The longer you’ve been around, the more you study and read, the more words you know. The King James Bible has a vocabulary of somewhere around 8,000 words of English. Shakespeare’s plays, written at the same time, uses over 36,000 words—a fair number of them invented by the Bard himself. The more words you use, the longer they are and, in English, the more that come from Latin roots, the more educated, erudite and intelligent you sound.

Sentence Length: as with words, the longer the sentence, the more educated the person sounds Children tend to put together sentences with roughly as many words as their age. Their sentences may seem longer because instead of a period, they tend to punctuate them with the word “and,” but functionally they’re very short. Mood also affects sentence length. A perfectly brilliant character who is angry may answer a request with the word “fine,” for example. In this case, that single word does a lot of heavy lifting.

Jargon: professions, clubs, hobbies and other social groups all have their own words and phrases for things. The proper use of specialized language marks not only a character’s membership in those groups, but often the era when they entered the group. A Viet Nam vet might refer to a helicopter as a “chopper,” while a Gulf War or Iraq war vet will likely call the same machine a “helo.” This sort of stuff is best learned either by experience in the group you’re writing about, or a lot of research including interviews with members of that group.

Words from a foreign language which a character, as a native speaker of that language, might insert into a dialogue, should be written in Italics. For example, “Bonjour and welcome to Maison D’oughnuts.”

Regionalisms: The Dictionary of American Regional English points out that in America we have all sorts of words which are standards in various pockets of the country. In much of the south, for example, if you want a carbonated beverage, you ask for a Coke. Elsewhere it’s a soda or soft drink or tonic. To broaden things, Australian English and American English have lots of words and expressions that don’t match with the British version of the language; and both British and Australian English have their own regional variants. Just how you write what a character calls something can tag that character’s background.

Dialect: Before 1960, writers often would render some dialogue in dialect. “Take dat guy out, youse guys, and do what you gotta do.” This is a mild example, but points out three problems with dialect that have curbed its usage. First, the writer has to misspell words on purpose, and deliberately mangling the language by rendering things phonetically is tough—especially remaining consistent with it. Second, and far more important, putting dialect into the mouth of a character can be classist and racist. The above example, for example, could be construed to denigrate individuals of certain ethnic groups and criminal classes. Third, most readers don’t like wading through dialect. It is, really, a foreign language and really slows down a book.

Generally speaking, correct use of jargon, including quirky phrases or the occasional foreign word, suffices to reveal aspects of a character’s background.

Take a look at the following sentences. Read them aloud to yourself, then quickly jot a note describing who the speaker is and anything you can glean about the speaker.

1) I say, pardon me, but would you happen to have any Gray Poupon?

2) No, daddy, the yellow kind.

3) Whoa, dude, wanna leave a little mustard for the rest of us?

4) Need anything else, hun? Mustard, maybe?

5) Now, when I was your age, all we ever had on hot dogs was mustard, and that was only when my grandfather took me to the boardwalk in the summer.

6) I put my name on that mustard, now someone’s used it all up. What the hell?

7) For the sophisticated palate, a Reisling usually pairs well with picnic fare, as the crisp yet sweet flavor contrasts gently with spices like mustard.

Clearly the sentences are linked by a theme. All of them are addressing an aspect of mustard usage. Each is appropriate for different characters, and each tells us specific things about the characters. If we were to use each sentence as a basic model for how a particular character speaks, shaping whole dialogues in that voice would be easy.

The Exercise

Take any simple sentence—perhaps an advertising slogan or, as with #4 above, something a waitress said to me at lunch—and rephrase it for different characters. Try the appropriate wording for insolent teen, confused senior citizen, arrogant but not terribly bright person, extremely bright but poorly socialized person, a gentle, helpful soul, an exhausted server at a restaurant and an excited college student.

Write out each rewording for five sentences. Once you’ve done that, offer a second selection that shows how they would respond if they were furious, and a third if they were ecstatic.

You’ll end up with fifteen sentences for each character. You get bonus points if you also generate a “catch phrase” for the speaker. From the examples above, the use of “Whoa, Dude” and “What the hell” would be (weak) examples of a catch phrase.

Please feel free to share some of the more interesting results in the comments below.

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

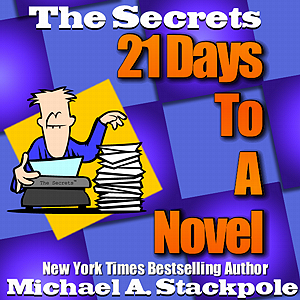

I’m really enjoying writing and sharing these exercises. I hope you’re finding them useful. I really want to thank everyone who has retweeted the notices, and especially those who have turned around and bought something out of my online store, like 21 Days to a Novel. The fact that these exercises caught enough of your interest for you to invest in your writing is a great incentive for me to continue.

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

March 13, 2015

Rogue One

It’s a bit of a shock, but also kind of fun, to find your Twitter feed blowing up because of a blockbuster announcement. Yesterday the news came out that the first Star Wars™ stand alone movie would be Rogue One. I can’t tell you the thrill that ran through me with the news. I don’t think I’ve stopped grinning like a fool since I first read about it.

There are a bunch of questions that have popped up, and I want to answer them as best I can. But, first, one thing really needs to be done.

Thank you!

Everyone has been unbelievably kind in their comments about my novels, including Entertainment Weekly. I loved writing those books and the time I got to spend in the universe. Marrying the comics and novels was a blast, second only to working with Timothy Zahn, Peet Janes and Aaron Allston. Every time I see a member of the 501st wearing a flight suit with a red stripe, I have to smile; and having boxes of action figures of my characters show up at the door is like having Santa visit at random.

But the reason Rogue One is getting made has nothing to do with my novels. The only reason the movie will be made is because of your reaction to and reception of the novels. The way you embraced them and the characters opened a whole new realm within the GFFA. Before you latched on to the eclectic collection of pilots, Star Wars™ was all princesses, pirates, droids and Jedi. Everyone else was expendable set dressing.

Let me share a secret: back when Rogue Squadron came out, no one (except for me) thought it would hit the New York Times Bestseller list. No one. We were off into unexplored territory, so when it hit, folks were stunned. And then, the week when The Krytos Trap was coming out, an obscure writer named Stephen King had five novels on the NYT list. Five! And everyone at Bantam was sure that the X-wing series’ Cinderella run was over.

And yet, because of you, The Krytos Trap knocked a King book off the list!

Without your support and enthusiasm, no one ever would have noticed the Rogues, and we’d not be waiting for this movie. So, again, thank you!

On to questions:

1) Has any reached out about having me write more X-wing novels? As of today, no. That’s a decision Disney and Del Rey and Lucasfilm will make, and probably after there’s a script in hand.

2) Has anyone at Marvel reached out about having you script an X-wing comic? Same answer as above. Writing the comics for Dark Horse was a blast, and I’d happily write more. What folks want is going to depend on how they want to develop the property.

3) Are you going to be asked to write the script? Nope. Hollywood uses scriptwriters to write scripts. While I’ve written scripts in the past, I’m not known for it. This project is so high speed they’re putting the best people on it.

4) Do you have any inside info on the movie? No. For this project, and Ep 7, I’ve actually been keeping myself spoiler free. I’ve not even watched trailers. I want to go into the theatre the same way I did in 1977 to watch A New Hope.

5) Who would you like to see play [fill in name pilot here]? Whomever the casting directors think is best for the part.

6) Do you have any secret wishes for Rogue One? Well, this is hardly a secret, since I’ve mentioned it numerous times at conventions. I wish the producers would hire Timothy Zahn and me (and I included Aaron when he was still with us) to be pilot extras in the film. Kill us off horribly, doesn’t matter. Or, since this film is set later, I’d love to be cast as a pilot instructor, with a uniform that has the name Horn on the breast in Aurbesh.

The reasons for this are simple. First, it would be a blast to visit the set and be part of the production. Second, it would complete a cycle. Tim and I were able to portray Talon Kaarde and Corran Horn respectively for cards in the Decipher Star Wars™ CCG. Being able to portray again characters that we created, or characters within a portion of the universe that we helped explore, would be a blast. Third, it would be a fun in-joke for readers, and a nice homage to the old EU.

Fourth, Tim and I could then go to conventions and not have to lug books to sell. We could just have photos of ourselves from the movies and sell those.

As I said above, I can’t tell you how thrilled I am to hear this news. It reconfirms for me the power of your love for the Rogues. I’ll be watching for news of the movie, and I’ll add new posts when/if I am able about any details I learn.

This movie will be about the Rogues, but it’s being made because of you. Thank you, and pass the popcorn.

March 11, 2015

High Intensity Writing Workout No. 5

This week’s workout expands a great deal on what you did in HIWW No. 4 because it’s all about character. Last week I had you creating a basic character, listing out a handful of facts about her, generate some goals and story ideas, then go back and change one fact. From there you got to deal with the consequences of that change.

This week things are going to be a bit more radical and are directly applicable to books you’ve written or are in the process of developing and writing. This exercise (or the pieces of it) provides a great way to generate some characters on the fly—whether you’re working from an existing character, or a character template. By character template I mean a rough model of what a character from that species/culture/era/profession is assumed to be like—the average Joe, if you will, for that sort of person.

The idea for this exercise comes from two sources. Almost thirty years ago, at the World Fantasy Convention in Tucson, AZ; Stephen R. Donaldson gave a talk in which he noted that in genre fiction, most characters tend to be a reflection of the main character. They mirror or distort aspects of him. Steve also noted that in non-genre fiction, the characters tend to mirror aspects of their world/environment—they become avatars of aspects of their society.

At roughly that same time, while working for Flying Buffalo, Inc., I spent a fortune (at least $30 which, at that time, was a fortune) on a business white paper that talked about methods for creating new products. I have found the methodology useful, especially when stuck in the middle of a story. (I’d credit the paper and author if I still had it, but I lent it to a friend and it’s never made its way back to me.)

The white paper suggested that to create a new product, one merely needs to look at an existing product and do one or all of the following:

1) Swap black for white

2) Turn it inside out

3) Turn it upside down

I know, all that for $30.

Fact is, the methodology has worked for me down through the years. In combining the two things we can create characters who are relatable to the main character (or exemplars of his society) and create instant points of tension. Let me expand on how this works for characters.

Swap black for white. With characters I look at swapping positives for negatives, or strengths for weaknesses or conviction for uncertainty. Clearly, if you have a pristine, pure, noble Paladin-esque character as your protagonist, creating someone who has been around, who gives in to vices, who can be cruel or craven, provides you with a nice contrast. If they aren’t enemies but, instead, have to work together, there’s plenty of opportunity for them to help each other grow. In the case of a villain, keeping the same traits as the hero, but skewing his goals and letting the ends justify any means to attain them, you get the shadow version of the hero. That has tons of great oppositional points to play with.

Turn it inside out. This point shouldn’t be taken literally. I think of this as making secrets public, and taking a public aspect and hiding it. Also, taking a fact the character holds to be true and making it false, or vice versa. One character’s source of shame could be the source of another character’s glorious notoriety. For example, a man whose family secretly made a fortune bootlegging now has to deal with a person who has unabashedly made tons of money through criminal activities, though he now claims he’s gone legit. This particular trick is great to use in the middle of a story, where the transformation happens to your main character, presenting her with a problem that she has to deal with. (News that she had a conviction for smuggling drugs could become public and cause a scandal; or an old confederate could be blackmailing her to keep it quiet.)

Turn it upside down. This aspect is where you apply the idea of a reversal of fortune. I did this in my novel In Hero Years… I’m Dead. The character Nicholas Haste (Nighthaunt) was a wealthy playboy socialite who saw his parents murdered in front of him when he was a youth. Leonidas Chase (Doctor Sinisterion) was the poor son of a couple whom he saw murdered in front of him as a youth, who was raised by a felonious uncle. Nick and Leonidas suffered the same trauma, but because of their circumstances, had entirely different life experiences.

Any and all of these techniques can be applied broadly, or to tiny aspects of the character. As noted above, if you use them to differentiate a character from the societal norm, you instantly have a rebel or outsider or outlaw or outcast, which is a great starting place for creating secondary characters.

This general technique also applies to pushing characters into worlds that have long been established. There are four story types/circumstances that can be applied to any character you want to inject into a situation:

1) Fish out of water (complete inability to cope with current circumstances).

2) Square peg, round hole (uncomfortable/hostile fit in current circumstances).

3) Innocents Abroad (utterly clueless about current circumstances).

4) Man Beneath Mask (appears to fit, but secretly is at odds with current circumstances).

To make any of the above ideas work, the author just has to ask:

1) Why is this so?

2) How does it manifest?

3) What are the personality aspects/facts that cause this to be true?

In answering these questions, you’ll generate all sorts of conflicts and the key points for growth. If you were to look at Luke Skywalker from A New Hope (an Innocents Abroad story) and answer the questions, you’d get:

1) He’s a farm boy whose only combat experience is killing rodents in a speeder.

2) Can’t fight, knows nothing of politics or history, thinks killing DeathStar will be easy.

3) He’s naive, he doesn’t trust himself or the Force, sees only the good in folks.

The answers to 2 and 3 provide you with challenges that need to be addressed in the story. He needs to learn to fight, to trust the Force, and to learn what’s really up with the politics in the GFFA. And, by the end of A New Hope he’s managed to make inroads on all of these points.

The Workout:

Take any character you’ve created, or any main character from a story you like, and apply the techniques above to create three alt versions of that character. Then, using the second set of techniques, thrust one of these newly created characters into a world and list out the growth points for that character so you can resolve the conflicts with her immediate circumstances.

Do this for three characters and you’ll master the techniques. Creating new characters and finding stories for them should be a snap after that.

Please feel free to share some of the more interesting results in the comments below.

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

I’m really enjoying writing and sharing these exercises. I hope you’re finding them useful. I really want to thank everyone who has retweeted the notices, and especially those who have turned around and bought something out of my online store, like 21 Days to a Novel. The fact that these exercises caught enough of your interest for you to invest in your writing is a great incentive for me to continue.

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

March 4, 2015

High Intensity Writing Workout No. 4

A lot of writers—especially beginning writers—choose to believe that writers fall into one of two camps: Plot-based writers and Character-based (or Organic™) writers. The problem with this view is that it suggests that one can have plots without characters and vice versa. And, I suppose, this is true in a general sense; but not in cases where the writers are writing top-notch stories.

This week’s exercise is designed to make this point fairly apparent. I’ll run an example, then provide you with a clean set of instructions.

The first step in all this is to create a character. Don’t waste a lot of time on this. It’s okay if the character is rather shallow. Like Sylvester, my character. (All I know about him is that his name is Sylvester and, apparently, he is male (or self-identifies as male).) To this I’ll had a handful of facts:

1) He enjoys non-team sports for participation.

2) He was raised Catholic but has since lapsed.

3) He’s not adventurous where food is concerned—meat and potatoes (burger and fries) are his preference.

4) He’s single, doesn’t date much and certainly not seriously.

5) He works a third-shift job in a food supply warehouse, noon to midnight, four days a week.

Looking at those facts, Sylvester doesn’t seem very remarkable. Of note, he appears to be a bit of a loner. That could be due to his job, since he works very odd hours so probably doesn’t have time to connect with friends. He likely runs or swims or bikes to keep fit. His lack of a dating life may also go to his job status, since his schedule isn’t likely to fit well with those of most women he meets.

Once you’ve generated that handful of facts, I need you to create three other things pertaining to your character. Create two short term goals (6 months or less completion) and a long term goal (a year or more for completion).

For Sylvester we have:

A) (short term) His brother is getting married, so he would like to find someone nice to take to the ceremony so the family won’t think he’s a loser.

B) (short term) He’s decided to take a class or two because he thinks he’s in a rut and wants to break out of it.

C) (long term) Wants to get a new job, white collar job, and have a career.

It’s pretty easy to see that his goals, if accomplished, would significantly change his life circumstances. He’d meet more people, become more social, might find a soulmate, might return to religion, clearly would ditch his horrid schedule, have more money and probably would have a much nicer life.

At this point I’m pretty sure you’re beginning to run scenarios for stories through your brain. Sly takes a class, meets a young woman who’s very attractive, but his efforts to woo her falter since he’s too white-bread when it comes to choosing restaurants. He makes an effort to try new things. She goes to the wedding. His family hates her, her family hates him, so together they work hard at the classes, fall in love, get good jobs and tell all the evil people in their lives to die in a chemical fire.

That’s probably the lowest-hanging fruit on the story tree, but it fits with all of the above and alters Sly’s life experience. At the end of the story his goals are accomplished and facts 3-5 are certainly no longer true. 1 and 2 are up for grabs, but certainly could be altered completely in the course of the story.

Now, back to the important part of this exercise. Look at the five facts about Sly. Change one. For example, we’re going to change No. 1. Instead of non-team sports, he loves playing team sports. He’s rough and tumble. He plays flag-football as an adult, maybe in a rugby league, and there’s the Saturday game with his buddies from high school at the Y from 4-5 pm.

That’s not much of a change, but it might change his goals. The long term goal, for example, might evaporate or face resistance because his basketball buddies also have blue collar jobs and wouldn’t want him getting above his station. (Well, above them.) That sort of attitude likely would kill his short term goal of taking classes, too. I’m also going to guess that because he’s only doing team sports for exercise, and has the grueling schedule he does, that he might have put on a few pounds—especially since burgers and fries come with beer after a game.

So, we’ll switch the classes short term goal to “lose 20 lbs,” which will make him a better athlete and might make it easier to find a date for his brother’s wedding. And with the wedding there, and his friends determined to preserve the past by never growing up, his longer-term goal will be to grow-up. (This supposes that his current life chafes a bit (in comparison, perhaps, with the wonderful life his brother has?).)

The new goal list, then is:

A) (short term) His brother is getting married, so he would like to find someone nice to take to the ceremony so the family won’t think he’s a loser.

B) (short term) Drop twenty pounds.

C) (long term) Wants to figure out what he’s going to do with the rest of his life, and start down that path.

If you take a look at where we are now, the story is more personal, more tightly focused and driven by his dissatisfaction with his life. He has his brother as an example of what he could attain were he to apply himself. He has his buddies who aren’t growing up and don’t want him to grow up. Definitely a coming of age/change of life story.

The immediate story idea that comes to mind for him which will connect all of those dots is that Sly gets into a yoga class at the Y, but it’s not going to make him lose weight. The instructor, an attractive woman who has rejected all the other guys on the team when they’ve taken a run at her, suggests that if he wants to lose weight, he’s going to have to work hard. He accepts the challenge. She says she’ll help him, but wants something in return: there’s a group of kids in the youth league that play on Saturday morning who just lost their coach. He takes that job on, she’ll train, help coach and so on. Things heat up between them, he chooses the kids team over his buddies; the instructor joins him for the wedding, it’s all good. And, through working with the kids, he finds he really likes coaching and helping others, so he finds his direction in life.

It’s key that you notice how such a simple change in Sly, when examined for consequences, generates new stories. The first isn’t completely foreign to the second, but they’re certainly not the same. And if we go back and change Sly’s job from four-twelves, to a sixty hour a week job with an investment bank, where he’s risen well beyond anyone he knows, things can flip again. Or if he’s very religious instead of lapsed, and has learned an unsavory secret about his brother’s intended. One simple adjustment to the facts reshapes the character, and reshapes the stories told about that character.

The Workout:

Just follow the steps. Lather, rinse, repeat five times, changing one fact each time. It doesn’t matter which fact you change. You might only change one, taking it darker or lighter with each step.

Step One: Create a character and list five facts about him or her.

Step Two: Create a simple profile of this character based on those facts.

Step Three: Create two short term goals and one long term goal that this character would realistically pursue.

Step Four: Briefly sketch out a story or two that achieves all the goals and incorporates (or alters) the five facts.

Step Five: Alter one of the facts, then follow Steps Two-Five again.

At the end of five passes through this process, you should have five different characters, about whom you could write many different stories. Understand that those simple adjustments are exactly the kind of thing that happens during the process of writing. It’s been my experience that when a character develops as the story is written, the story becomes the stronger for it. This process isn’t something to fear, it’s something to embrace. Sure, it may complicate revisions as you bring the old stuff up to speed with the new, but the story will be so vibrant and entertaining, you’ll be overjoyed you went with the changes.

Please feel free to share some of the more interesting results in the comments below.

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

I’m really enjoying writing and sharing these exercises. I hope you’re finding them useful. I really want to thank everyone who has retweeted the notices, and especially those who have turned around and bought something out of my online store, like 21 Days to a Novel. The fact that these exercises caught enough of your interest for you to invest in your writing is a great incentive for me to continue.

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

February 25, 2015

High Intensity Writing Workout No. 3

This exercise harkens back to what we covered in High Intensity Writing Workout No. 1. You’ll be using some of the skills you developed there to get through this workout.

One “problem area” (to keep the workout metaphor working) for most writers early on in their careers involves tunnel vision. Whether working from notes or an outline, they focus in on the factoid they need to get across, and stay locked in on it no matter what else might come up.

For example, the outline says that Cliff and Sally are on a second date, and it’s supposed to go horrendously badly. Cliff really wants to get Sally to try out some cool favor of ice cream at some chain place. He insists. Sally gets stiffer and colder, then reminds him that not only has he forgotten that she’s lactose intolerant, but she’s gluten-free and, on top of that, she hates multi-national chains. She even had “buy local” as an interest of hers on Tinder, where they met, for crying out loud. He doesn’t listen to her, and she hated putting up with that stuff with her ex, and she’s not about to do that now with him.

Okay, pure disaster. Worse than a disaster. This is a dating atrocity. And, the fact is, I’m fairly certain, if the writer does that scene any justice, Cliff and Sally ain’t having a third date. In fact, they’re both going home and destroying any evidence of a first and second date.

But, if we back up a little bit, and are flexible, other aspects of the characters might open up. And by “other aspects,” I mean things that the writer may not have even guessed about the characters.

Thus, Cliff and Sally are walking along and he sees the ice cream place. He looks longingly. She notices and asks what’s the matter. He explains that co-workers had raved about the flavor of the month and he’d forgotten about it until just that moment. Then he quickly adds, “But I know you don’t do ice cream, and wouldn’t be caught dead in there, so it’s cool.”

(At this point, we’re off script as far as the outline is concerned. Beyond this point, for some writers, all that exists are dragons…)

Sally looks up at him, slipping her hand through the crook of his elbow. “It’s okay. You can have ice cream. I’m not the diet police.”

“No, look, it’s important to me, since we’re out together, that we do things together. I don’t think you want to sit and watch me eat ice cream.”

“I can think of better things to do, true.” She smiled. “But I’m getting the impression that ice cream is kind of important to you.”

Cliff sighs. “Okay, promise me you won’t hate me or anything, right?”

“I promise.”

“Okay.” He exhaled slowly. “When I was a kid I played Little League Baseball. We weren’t the Bad News Bears, we were the Morbidity and Mortality Newsletter Bears. We couldn’t have won if Ebola wiped out the rest of the league. We practiced with a tee, and most of us struck out.”

“You were bad. Got it.”

“But my grandfather, after every game, he would load us all up in this old van and take us out for soft-serve. And when we finally did win a game—it got called on account of a tornado, so we only won by an Act of God—we got Sundaes.” Cliff gave her a sheepish grin. “Other folks drown their sorrows in beer, celebrate with Champagne. For me it’s a cone, or something with sprinkles.”

Sally glanced down for a moment, then nodded toward the ice cream store. “So, being out with me, cone or sprinkles?”

The first of the two things you’ll want to notice here is that we didn’t make the date a disaster. Frankly, disasters are easy to manufacture. Having Cliff and Sally get closer means that any disaster will be something the readers feel more acutely. It’s the difference between readers thinking Cliff is going reveal himself to be an insensitive clod and fearing he’ll reveal himself to be an insensitive clod. In this latter case, the readers are invested in him, and in seeing the two of them get together, which is what you want.

The second thing is this: the conversation appears to be about ice cream, but it’s really not. Cliff is revealing a vulnerability. You can imagine, from the above, that his childhood wasn’t perfect. His grandfather appears to be his custodial parent, he drives an old van so they likely didn’t have much money, and Cliff hung out and played with lots of kids who were losers (at sports, anyway). Just in that story about Little League you’ve hinted at tons of things which can later get worked back into the story, like having teammates—no longer losers—show back up in his life when he most needs the support.

Writing and developing a story is a cyclical process. You develop what you can, then start writing. What you write will expand on or subtract from or completely alter bits and pieces stuff you developed. You make changes, account for the consequences of those changes, and keep writing. The cycle starts again.

The cool thing is that when you allow for the story to change and find a path which is true and interesting for the characters, it will be more interesting for you and for the reader. This sort of organic development adds a lot of energy and depth to stories.

The Workout:

I want you to find/make up some random bits of dialogue. Eavesdrop on a conversation at a coffee shop, pull a line from a book or a movie (or Cliff and Sally’s conversation), or yank something from a news story. You can start with one or two, but probably need to follow this exercise through a half-dozen to get where the idea is comfortable.

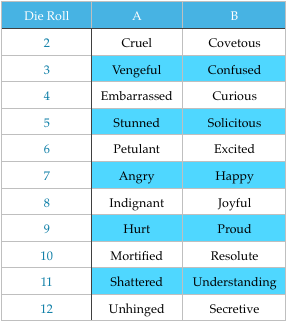

The chart to the left is a remnant of my game designer training. You can pick an emotion/aspect off it, or roll two six-sided dice to generate a result. You can choose which column, A or B, you want to start with, but if you roll doubles (same result on both dice) you switch. Whatever descriptor you get, you use to characterize the sentence with an attribution tag.

Let’s say our sentence is “I really wanted chocolate ice cream.” I roll the dice and come up with angry. So I write:

Cliff pounded his fist into the wall. “I really wanted chocolate ice cream.”

From there, you run the dialogue for another 5-6 lines, hitting a back and forth exchange. For each new line, you roll the dice and characterize the new line with that emotion. In this case I roll an 8 and get “Indignant.”

Sally lifted her chin. “That is chocolate. From Ice Castle. A month ago you said that was the best chocolate ice cream you’d ever had.”

“It is?” Blood drained from his face. He stared at the spoon and the half-melted glob on it. “But it doesn’t taste like chocolate. Not even close.”

Her expression froze. “I can smell the chocolate from here, and a woman at the store, she tasted a sample and said it was better than sex.”

Cliff sat down hard, the spoon clattering in the bowl. “What’s wrong with me? I haven’t had a problem like this since…” He swallowed hard. “Oh my God, they didn’t get all of the tumor.”

(The random roll results after Indignant were: mortification, stunned and stunned.)

While this example went dark fast, if we’d started on the happy track, or maybe with something on the top or bottom of the chart, we’d have been off into entirely different territory. Regardless, until I got those dice rolls, I didn’t know poor Cliff had had a brain tumor. Or someone could have been working black magick on him, or an Alien larva could have been eating its way through his brain or…. But, having discovered that fact, now I deal with it.

Once you’ve run five lines, start with another emotion and see where that conversation goes. You may only need to do it twice per sentence to get the idea, but four times ought to really let you master the concept.

So, go ahead and give the exercise a try. And keep that chart handy. If you’re working on a story, a random roll of some dice might get you thinking in new directions. Just having someone react angrily to something that shouldn’t make anyone angry will get the juices flowing. Better yet, when you think you’ve written yourself into a corner, a shift like this will show you there’s a lot more possibilities out there.

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

February 18, 2015

High Intensity Writing Workout No. 2

One of the goals of any good writing is to pack a lot of information into as few words as possible. The biggest culprit in preventing this is the verb “to be.” The reason is simple: the verb is the lowest-common verb—it applies almost anywhere. But it is weak and flabby and applied too broadly. In writing I prefer to use it only when I’m trying to describe [current state of existence].

I do my best to eliminate the verb “to be” as much as possible in my books and stories. That’s not always easy to do since, sometimes, you do want to describe something’s current state of existence. Dialogue is also an exception to this drive. That’s not to say I still don’t try to cut the word out of dialogue, but using “to be” is part of dialogue. People just speak that way.

Here are some examples of what I try to eliminate:

1) Passive constructions. Most editors hate passives, so eliminating them is a good thing to do. Passive occurs when the object of the verb appears in a sentence before the subject.

Passive: The ball was hit by the bat.

Active: The bat hit the ball.

Dynamic: The bat smashed the ball

In eliminating “to be” we get rid of the passive construction, as you can see with the active example. The Dynamic example occurs because we find a more descriptive verb to substitute for the rather generic hit.

2) Lazy construction: One of the greatest overuses of “to be” is in description. The sentence, “The car was red,” is perfectly good and true. The car’s state of existence, as refers to color, is accurately describe as red. But we don’t need a verb there.

If we eliminate “to be” we get “The red car…” This isn’t a sentence, since it lacks a verb. So we build it out with “The red car sped around the corner.” Chances are very good that this one sentence would have been built out of the following paragraph: “The car was red. It was going fast. It took the corner quickly.” Granted, that’s how a 7 year old would write it. An adult might well expand on our simple example with “The red car screeched around the corner, smoke billowing from its tires.” Much more visual, and even auditory, for one less word than our little paragraph.

3) Distancing: A sentence like “The man was writhing on the ground,” is perfectly good, save that adding “to be” eliminates the immediacy of what’s going on. Now, if the narrator is the sort of person who would distance himself, that’s fine. Or if circumstances put her in a position where she would distance herself, that’s also fine (as if she were at a distance, using binoculars or a closed circuit TV system, or is reviewing video of a previous act). In the cases where we want the reader right in there, though, eliminating “to be” makes things more immediate.

Distant: The man was writhing on the ground.

Immediate: The man writhed on the ground.

Intimate: The writhing man’s motion churned blood and dust into ochre mud.

True, Distancing and Lazy Construction are actually the same deal, but the use of another verb in there complicates things and provides more solutions in the former situation.

The workout for this week is simple. Take any story or a chapter of same that you’ve written, and go through and eliminate* the verb “to be.” Print the piece out and just circle all the times you use it. You can even use your computer to count the instances of is/was/be/been in the sample before you do any editing, and again after you make the changes. Substitute the most dynamic verb or most intimate construction you can. Don’t worry about the piece seeming overwritten–leaning it back out again will be easier than building it up.

Though your overall word count won’t increase too much, what you’ll find is that your text is much richer. Your readers will be getting more bang for their buck, which provides the kind of value which will bring readers back time after time.

*This exercise could be seen as a contravention of my dictum that you should never rewrite before you finish a piece. So, use a piece that you’ve finished. Or, in spotting the use of “to be” in a current work, use that as a teaching tool to get you to eliminate the word as you go forward. With a bit of practice, you’ll clip “to be” without thinking about it even as you lay down the first draft.

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

February 10, 2015

High Intensity Writing Workout No. 1

Because I’ve started teaching online writing classes through Arizona State University’s Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, I’ve been having to put together exercises to help students understand and master a variety of techniques.

One of the things I’m pretty much death on is using he said/she said or their variants in dialogue. I learned long ago, from the very talented Hugh B. Cave, that dialogue tags made dialogue very choppy. In addition, dialogue tags don’t engage the reader. They tell the reader what to think, which means the readers aren’t required to do any processing of the situation. Dialogue tags also tend to be breeding grounds for adverbs, which can lead to incredibly purple prose. Most importantly, if each character has a characteristic way of talking, the tags become an annoying redundancy.

I am aware that a lot of writers maintain that dialogue tags like “he said” are so common to be invisible to the readers. I have to ask, then, why use them? (The answer is that we’re paid by the word…) While I like money as much as any other writer, I prefer a higher information-to-word ratio in my writing. It really lets me have more going on, and to bury more material to connect up with later on.

Take a look at these two writing samples, one written with dialogue tags, one with attribution text.

Dialogue Tags:

“How is it you’re here?” Hank demanded.

“You couldn’t think I wasn’t going to make an effort to be here.” Sally replied.

“You can’t stop me,” Hank said adamantly. “My mind’s made up.”

“I can try,” Sally sighed. “If I fail, then I can support you.”

“Things are going to get very messy,” exclaimed Hank.

“Tell me something I don’t know,” Sally chuckled sadly.

“You aren’t going to like it,” he told her angrily.

“You can’t frighten me off,” she counter defiantly.

“Remember the woman you saw me with?” Hank asked.

“The redhead?” she replied.

“Yeah. Back when I told you I wasn’t married, I lied,” he sneered. “She’s my wife!”

Attribution tags:

Hank’s head whipped around. “How is it you’re here?”

Sally glanced down, refusing to meet his gaze. “You couldn’t think I wasn’t going to make an effort to be here.”

“You can’t stop me. My mind’s made up.”

“I can try.” She hugged her arms around her middle. “If I fail, then I can support you.”

Hank shook his head. “Things are going to get very messy.”

“Tell me something I don’t know.”

His eyes narrowed. “You aren’t going to like it.”

Her chin came up and she stared him straight in the eye. “You can’t frighten me off.”

“Remember the woman you saw me with?”

“The redhead?”

“Yeah. Back when I told you I wasn’t married, I lied.” His hands curled into fists. “She’s my wife.”

Compare the two samples. It’s best done if you read them aloud. I think you’ll notice two things.

1) The dialogue tags really cut into the flow of the first sample. They slow it down with information you don’t need.

2) The second sample flows more easily. In addition it’s much richer. When you look at the first line, it should be fairly clear that Sally has come up behind Hank, surprising him. Her response, in not meeting his gaze, betrays her being shy or ashamed; yet later she looks him in the eye, when he’s trying to get her to go away. And that last line, his hands curling into fists, what is he feeling? Anger? Frustration? Sorrow that he’s bound to this other woman, when he’d really rather be with Sally, but honor and duty demand he deals with her? In general, that second sample provides the reader with a lot more information to help shape the world and the characters.

The Exercise:

I want you to take the raw material below (the same sentences I used) and add attribution tags that round it out. In the samples I used, Hank and Sally are, presumably, peers and perhaps romantically involved. But you get to decide what their relationship is. Imagine that dialogue if Hank is 21, and Sally is his mom. Or that Sally is 33 years old, and Hank is her 60 year old father. Or they’re brother and sister, and this redhead would be Hank’s second wife. Or swap it around, Sally starts the dialogue, and the redhead is her wife.

Go ahead, do the exercise, and then paste your version into the comments below. For reasons far to numerous to mention (and most having to do with legalities), I won’t be critiquing the results. (If you want me to critique your work, you can apply for the Your Novel Year program at Arizona State and get into the classes I’m teaching.) If you choose to comment on anyone else’s samples, be gentle and constructive.

Raw material.

“How is it you’re here?”

“You couldn’t think I wasn’t going to make an effort to be here.”

“You can’t stop me. My mind’s made up.”

“I can try. If I fail, then I can support you.”

“Things are going to get very messy.”

“Tell me something I don’t know.”

“You aren’t going to like it.”

“You can’t frighten me off.”

“Remember the woman you saw me with?”

“The redhead?”

“Yeah. Back when I told you I wasn’t married, I lied. She’s my wife.”

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

October 27, 2014

Don’t Miss These Deals!

The folks at Storybundle.com have put together two bundles where you get to set the price for what you buy. And these are smoking deals.

First up in the Nanowrimo writing package. This is an incredible value. For the $20 I’d ask for my 21 Days to a Novel, you get ten writing books by some of the best writing instructors in the business—including my 21 Days To A Novel. Every time I look at this package, I wish I could have somehow sent it to myself 25 years ago. Not only will you get instruction in the craft of writing by stunningly great writers, but also get clued into the business demands that all writers face now. If you are thinking of a career, this is the best package you could ever buy to get yourself started, and for only $20!

Next is the Urban Fantasy bundle. Ten books, ten great authors, a wealth of urban fantasy stories. This bundle goes for $20 as well, which a 60% discount off retail for the books. My Tricknomancy is included in the mix, as well as work by Kevin J. Anderson, Jim Butcher, P. N. Elrod and Carole Nelson Douglas. Half the books in this collection are exclusive to it, so this is a once in a lifetime opportunity.

Please, check these deals out, and get the word out about them (RT, please). These are two great deals that you don’t want to miss.

July 31, 2014

My Latest Book: The Crusader Road

The Crusader Road is my latest book. It’s my first venture writing fiction in the Pathfinder™ universe. I had a lot of fun writing the book, and I think it turned out pretty well. If you want an unbiased opinion on that issue, you can read the review at Roqoo Depot.

One of the most interesting bits of writing the book for me was the fact that one of the main characters is Jerrad, a thirteen year old young man who is rather slight for his age and no where near the heir to the heroic tradition established by his father. I’ve written young men before, but none quite so young and none so far from when I was their age. It isn’t that its hard to remember back then, but that the issues I faced when thirteen were decidedly different than the ones Jerrad faces. When I was his age, my biggest trauma was trying to choose between buying lunch the cafeteria or saving the money to buy the new Doc Savage novel. While that is an important issue, Jerrad isn’t worrying about eating lunch as much as being eaten for lunch.

I really enjoyed being able to root around in the Pathfinder™ universe. It’s a really intriguing setting. If I had a gaming group, I’d definitely be running adventures in that world. It has an eclectic mix of elements that really appeals to my sense of the heroic in fantasy, but allows just enough exotica to make the setting something I can have fun exploring.

Roqoo Depot also interviewed me about writing the book. You can read that article here. I’m already scheduled to do two signings for the book at the Paizo booth at Gencon: 8/15 11AM-12PM and 8/17 11AM-12PM; though if you catch me otherwise at the show I’d be happy to sign.

July 18, 2014

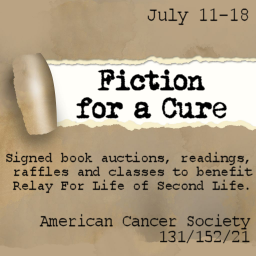

Fiction For A Cure: Friday Line-up

Fiction For A Cure, which is a mega-event in the Relay For Life of Second Life’s fundraising campaign for the American Cancer Society, wraps up today. We have two incredibly special events to finish the drive.

At 3 PM PDT/Second Life time, New York Times bestselling author Diana Gabaldon will join us for a reading. Yes, that Diana Gabaldon. She agreed to give us an hour between coming off her author tour and the ComiCon hoopla concerning the Starz Outlander series. In addition, she’s donated two signed books for the live auction.

At 6 PM PDT/Second Life Time, we’ll hold our Live auction. You definitely want to hit the link just to take a look at all the fantastic things that authors have donated to the fundraising effort. I’ll be hosting the live auction, and this is the perfect chance to start or fill out your book collection. Even better, you can get a head start on your holiday shopping.

If you can’t make the auction, but would still like to help the effort, you can go directly to our fundraising page to make a donation. Your support is very much appreciated.

But, really, you want to join us. The live auction features incredibly rare items you’ll likely not see again. Your money goes for a great cause, and you get fantastic rewards for helping out.