Shannon Rampe's Blog, page 2

December 1, 2023

Microblog: NaNoWriMo 2023 Field Report

31,538 words! I call this #nanowrimo a win.

National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), the annual event in which aspiring authors around the world set out to write a 50,000-word novel in a single month, just wrapped, and writers everywhere are taking today to massage their wrists and take a breather (just kidding - I wrote another 1900 words today in addition to this blog post).

Instead of trying to write a 50,000-word novel, my goal this NaNo was to finish Act 2 of the novel I am already working on (titled "The Radiant and the Corrupt"), which I estimated was going to be a slightly more achievable but still substantive 30,000 words. (For the non-writers reading this, 20,000-25,000 words is roughly a hundred pages. So I was still looking at a target of 100-150 pages to write in November.

There was no reason for the insurgents to cause them harm, nor the Cult Militants for that matter, but Val had been in war-torn cities before; there was no reason or logic in a place like this. There was only mob rule, fear, and death. A younger Val would have marched through the city, ready to face whatever conflict his destiny brought him. Such hubris had nearly gotten him killed and had gotten others killed needlessly. There was enough death. He didn’t need to be the cause of more.-from "The Radiant and the Corrupt"

I managed to get words in almost every day, usually exceeding my 1000-words a day goal, and closed yesterday at just over 31,500 words. I did NOT finish Act 2, which, it turns out is going to require two more chapters to finish, but I should hit that milestone this weekend.

I also made an important structural realization about the novel this month. When I initially outlined the work, I had a huge story. After I completed Act 1 at more than 45,000 words, I was afraid this novel would be over 200,000 words long! A novel of that scale is not only incredibly difficult to sell to publishers, it's incredibly intimidating to try to write. But in a decision that I hope will make my agent much happier, I figured out a way to restructure the story into two more manageable volumes. So now instead of having 120k-150k still to write, I now probably have another 40k or so to reach the end of the first draft. Whew!

I want to give a shoutout to fellow NaNo writers Tanner and SpaghettiSyntax from the Frogpants Community who cheered me on this month. The best thing about NaNoWriMo is, without a doubt, the camaraderie it inspires among writers. Writing is a solitary, lonely business where you spend hours a day for weeks, months, and sometimes years working on something that no one else know anything about. During NaNo, we writers support each other on as we run this month-long marathon, and it feels great. Thank you Tanner! Thank you SpaghettiSyntax! And congratulations on you own writing accomplishments this month.

Finally, extra special thanks to Denise who kept me fed and sane during this month-long sprint. She also read the chapters as I produced them, provided constructive feedback, and listened to me alternate between gleeful excitement and confused dismay as I smashed my way through this story.

In closing, here's one more snippet of the (very raw) first draft for you to enjoy:

Patish shrugged. “Most of the time, I’m just a scout and a messenger. I know my place. Marduk is trying to change things for the better. I know she picked you. That makes you pretty amazing in my book.”

Inkosa felt wretched. Patish believed she was some kind of hero, a resistance fighter for Marduk. But it was a lie. She was no hero. She was just a scared, stupid girl. She’d done something terrible and now everyone else was paying for it.

Patish placed a hand on her arm. “Did I say something that upset you? I’m sorry.”

She shook her head, desperate to banish her feelings and just act normal. “It’s not you. I’m just not who you think I am.”-from "The Radiant and the Corrupt"

,Subscribe to my newsletter for updates on "The Radiant and the Corrupt" and other projects. Share this on social if you like it. And let me know what you think! Did you participate during #nanowrimo? Did you hit your goal? Will you keep going on your project now that the month is over? How did it feel?

November 16, 2023

DMing Dragon of Icespire Peak - Part 3

This blog series teaches new and returning Dungeon Masters how to run the Dragon of Icespire Peak (DoIP) Campaign from the D&D Essentials Kit and provides advice and guidance for being an effective DM. Check out Part 1 and Part 2 of this series.

Welcome to Part 3! At this point, you have gathered your players, run Session 0, created characters, made some initial notes about the campaign, PC backgrounds, and NPCs in town, and run your very first session. Congratulations! You’ve completed the most challenging parts of being a Dungeon Master. From here, it’s all fun!

In this part of the guide series, we’ll look at how to hook the players during the early levels of the campaign, identify the plot threads that will develop later in the campaign, and discuss some of the quests.

Recap From Session 1In Session 1, hopefully your party found their way to Phandalin, met some of the townsfolk, and completed one of the three starter adventures. If they didn’t make it all the way through the first adventure, that’s fine, too. It just means you might have a bit more work to do for Session 2 since the party will have several options presented and you’ll have to prepare for all of them.

After the first Job Board adventure is completed, make sure the party gains a level. This will do a lot to increase their survivability in the early levels!

Make sure after you complete the first session, you spend a bit of time making notes on what happened.

Did the PCs seem particularly interested in any of the NPCs in Phandalin? Perhaps someone they are suspicious of or someone they particularly want to help? How did the PCs get to Phandalin? Did anything interesting arise as a result? How do the PCs know each other? How did they interact with one another during the session? Did any relevant PC background info come up during the session?Capturing notes like this after each session will provide you with additional tools in later sessions to develop a narrative that is compelling and feels special and unique for your party.

Campaign Structure – The Early CampaignLet’s review the structure of the campaign as written. Per the campaign guide, the party should complete two of the jobs listed on the Job Board, at which point, you give them access to three additional quests. After two of these are completed, three final quests go onto the Job Board.

There are several quests presented in the adventure that never appear on the Job Board. The party won’t stumble across any of these until at least the fourth sessions – or perhaps later. The only one you might want to look at is the Shrine of Savras quest, since the party could conceivably stumble across this as soon as Session 4.

The Job Board structure never tells you to remove incomplete quests, but I would recommend that you take them down after a session or two. This gives the impression that—unlike a video game—this world moves and changes over time. Doing every side quest before pursuing the main quest like in a video game isn’t always an option in D&D. The players will feel like their choices are more meaningful. They’re choosing between one quest and another.

Also, as we discussed in part 2 of this guide, the Job Board gives players a nice feeling of agency in deciding what quests to choose, but you can choose to leave quests off the Job Board if you don’t like them or if you want to focus your players’ attention on one or two quests in particular.

The Job Board is the advertisement for adventure, but which adventure will the PCs choose? As-written, there’s no real reason for the party to pick one adventure over another because they’re disconnected and don’t have any story elements to make them narratively significant. You’re going to change that.

Much like the first session, you want to look at what the players gave you during Session 0 and especially during your first session. You made notes about which NPC they liked or disliked. Make sure that NPC has an opinion about which quest they should go on next. You could have that NPC offer an additional reward for a particular quest, or you could connect one of the quests to one of the PCs backstories.

Here are a few ideas you can borrow to narratively spice up the early game quests:

Dwarven Excavation

Toblen Stonehill is acting as an agent for Halia Thornton and is trying to buy up all of the gold mines in the region. He sees the excavation site from the Dwarven Excavation Quest as prime real estate. The only problem are those pesky dwarves, Dazzlyn and Norbus. If the PCs make sure they “disappear,” he’ll cut them in on a share of the profits. Replace Dazzlyn or Norbus with a NPC from one of the PC’s backgrounds – a cousin or brother or old friend. Replace the shrine to Abbathor with another evil god—preferably one directly opposed to one of the PCs. Be sure that one of the townsfolk mentions this evil shrine being uncovered by two foolish dwarves.Umbrage Hill

Adabra Gwynn can be an acolyte of whatever god the party might be interested in supporting – Chauntea is fine but many other gods could serve just as well. If the party manages to scare off or bargain with the manticore from Umbrage Hill, it should make an unexpected return appearance later in the adventure, as a friend or foe depending how the first encounter plays out. If the party is looking for a merchant in town that sells magic items, potions, scrolls, and the like, you can give Adabra this role, which will encourage the PCs to develop a positive relationship with her and allows you to leverage her as an important NPC in later adventures.Gnomengarde

Replacing one of the NPCs in Gnomengarde with someone from the PCs background is a good way to setup this quest. Korboz’s madness is said to be triggered by a mimic attack. Instead of the mimic specifically, the madness could have been triggered by dragon fear incited by the white dragon Cryovain, establishing early on the harm the dragon is having on the region. You can also seed a clue in Gnomengarde to one of the secondary quests later in the adventure—for example, the party might stumble across an old map with the symbol of Savras on it (DC 15 Religion or History to recognize).With each quest, try to create narrative hooks and connection points like this. Doing so will help to create a broader sense of purpose for the PCs rather than just go kill the monster and get gold as a reward.

Speaking of gold…

Shopping and Gold SinksMost of the quests in DoIP reward the players with gold, but the shops in town don’t carry anything interesting besides mundane items. Adabra sells potions of healing, but that’s it.

I would highly recommend you enlist Adabra Gwynn or someone else to sell not just healing potions, but other minor magical items as well. You can have a rotating list of these that change every few days of game time. This gives the party something to spend their hard-earned cash on.

I do recommend taking shopping time “offline” though – your game time is precious and spending it having players pour over equipment lists isn’t the best use of your time or theirs. Instead, just have players equip and update their character sheets before the next game session.

After the players complete a few quests, you should offer then a home base in Phandalin. There are many ruins in town, including Tresendar Manor (described in Lost Mine of Phandelver) that Townmaster Harbin Wester might offer to the party for a discounted sum of gold.

Having a base of operations will not only give them something to spend money on, more importantly, it will help to strengthen the players’ feelings towards Phandalin. They’ll start to think of it as a home, a place to be protected.

That way, when you threaten Phandalin later in the campaign (cue maniacal DM laughter), the players will be really motivated to defend it!

Final Tips

Final TipsFirst up, during the first three or four sessions, don’t worry too much about the broader narrative arc you’re building. Trust yourself that it will come together as things move forward. Just try to seed lots of interesting hooks and narrative connection points and see what your players pick up on. Don’t try to force anything – let them decide what’s important. As the campaign progresses, you can start to reinforce their decisions by leaning into their choices and building towards a crisis that’s intimately connected to the threads they chose to follow, but you don’t need to worry about what that is now. Just let the game flow and see where it takes you!

Second: always remember as well that nothing in the campaign is set in stone until your players see it at the table. You may have decided that Toblen Stonehill is greedy and conniving, but perhaps one of your PCs misinterprets Toblen’s behavior as being altruistic and your party seems to like this. There’s absolutely nothing stopping you from changing Toblen on the fly. Or maybe you plan for the party to visit Butterskull Ranch where they’ll learn about the Shrine of Savras from a strange old hermit. But the party never decides to go to Butterskull Ranch. You can just move that old hermit somewhere else.

Don’t be afraid to change details of the campaign on the fly to suit the needs of the game. Your players don’t know when you change things. In their minds, the world they’re exploring just is. As long as you don’t tell them you changed something to achieve a particular outcome (and you shouldn't), they’ll just assume that’s how it was supposed to be all along.

Final tip – when the PCs return to Phandalin after each quest, make sure to show small changes. Have the important NPCs in town start to recognize them. Change the inventory of the shops. Introduce new NPCs or have others leave. By showing a few small changes like this, it will help to create the sense that the world the PCs are exploring is a living, breathing place, particularly if those changes are connected to the quests or the PCs decisions.

Keep Crushing It!I hope you are having a great time running Dragon of Icespire Peak. Make sure to lean into the parts that are the most fun for you as well. As the DM, you are a player as well and this should feel like fun, not work or stress. If you find that you get stressed by improvising, then spend extra time in advance of the game making some notes and reviewing maps and take advantage of building a campaign notebook. If pre-game prep feels like work, then try minimizing your prep using the Lazy DM method.

Final ThoughtsWhat happened during your first few sessions? Do you have questions about how to handle specific encounters? Advice for other DMs? Ideas for where your campaign will go from here? Post your questions, thoughts, and feedback in the comments below, and share this blog on Facebook, Reddit, or Discord.

If you want more D&D tips, articles on sci-fi and fantasy, and a free story, be sure to subscribe to my newsletter at https://www.shannonrampe.com/signup.

November 9, 2023

The Third Rail in Red Rising

Note: the following blog post contains spoilers for Pierce Brown's Red Rising. If you prefer a spoiler-free review, check out the in-line Goodreads review below.I have been thinking about the popular sci-fi novel Red Rising by Pierce Brown this week, having recently finished reading it.

Red Rising succeeds at a lot of things: the worldbuilding is deep and intricate but fed to you at a place that is easy to digest and the terraformed Martian setting is interesting. The pacing, particularly in the later half of the book, is excellent, pivoting between well-written action scenes and slower-paced dramatic scenes between characters filled with narrative tension that pull you rapidly towards the end of the book.

Equally, there are plenty of things to criticise. The opening act of the book is almost laughably derivative of the Hunger Games. The society based on characters being born into different colors (reds, pinks, browns, all the way up to golds, the best of the best) was lacking in nuance or subtlety as presented. It's too easy to apply our real-world social orders onto this society in ways that are overly simplistic. There are also arguments to be made that Darrow, the protagonist, is a bit of a "Mary Sue" (a character who is good at everything, despite having little reason for their abilities), though personally I found that Darrow's competency in some areas was balanced by his lack of diplomacy and understanding of other characters earlier in the book.

However, the thing I wanted to talk about here that I found interesting was what makes Darrow a compelling character, both how Brown succeeded and how he failed in the novel. Early in the book, the author establishes that Darrow's wife Eo reveals to Darrow the vile truth of the society which they belong to, where Reds like them slave away in ignorance and poverty unaware that the Golds live above them on the surface of Mars in a paradise. She is then promptly hanged for her crime by the Archgovernor, himself a Gold. Darrow, a Red, is predictably sad and angry, and this compels him to join a resistance group known as the Sons of Ares who seek to overturn the rigid society where Golds sit at the top and Reds sit at the bottom.

Lisa Cron, in her book Story Genius, explains that one of the strategies to create a truly compelling protagonist is to ensure there is some traumatic or transformational event in their backstory that establishes a powerful belief or drive within the character that will continue to influence their actions and decisions later in life. When this belief comes into conflict with the events of the story, it puts pressure on the character to act in ways that propel the story in interesting directions. Cron calls this the "third rail," referring to the electrified third rail that powers a subway or tram. I think it's a great concept and in many books it can create truly compelling characters where we root for the character to do one thing to solve their problems but their fears or false beliefs drive them to do another thing.

Brown tries to establish Eo's death as a third rail for Darrow, but for me it completely fell flat. Throughout the book, Darrow repeatedly laments how he misses Eo or how he remains angry with her for the events that transpire in the opening scenes. But instead of creating narrative tension or causing me to care about Darrow, I just groaned and rolled my eyes. Why was Darrow's third rail dead for me as a reader?

A few things come to mind. First is that Darrow and Eo are sixteen. They are married, but little more than children, and only married a short time. While I believe that a young Darrow would indeed be traumatized by the death of his young wife, I, a 40-something reader, found it much harder to buy into the notion that Darrow was deeply motivated or compelled by Eo's actions and ultimately her killing. This is because partly they're so young, but mostly because there's so little time shown with Eo that we get no sense of Darrow and Eo's relationship. Eo comes off as little more than a cardboard cutout of a character.

Darrow is also remarkably ignorant, selfish, short-sighted, and unaware, completely acceptable traits in a sixteen year-old. But again, I found it difficult to see such a naive and selfish kid motivated to suddenly try to change the world; an act that requires vision, motivation, and self-sacrifice. Finally, I personally think that motivating a character by killing their loved one is cheap. It's like showing off how evil a villain is by having them kill a dog. It's an age-old trope, particularly when it comes to male protagonists.

My complete and total lack of belief in the third rail of the book almost drove me to abandon it. I didn't though, and I'm glad. The second half of the book was far more interesting. Here, Darrow develops complex relationships with the other kids at the school - real relationships that have depth and complexity rather than the underdeveloped, barely-shown relationship with Eo. It's here that the story gets its power: Darrow's friendship with Cassius, whose brother Darrow was forced to murder; his struggles against Titus, a violent sociopath whom Darrow puts to death in a way that weakens his standing with the others; his relationship with Mustang, who causes him to continually question her motives and his own feelings. It's the relationships with these characters, and others, that make Red Rising such a compelling story. I hope that in subsequent books the author continues to leverage such compelling character relationships to drive the story forward. If so, it should be a great series to follow.

What did you think of Red Rising? Did you buy into the third rail of Eo's death motivating Darrow? Were there other elements of the book that hooked you or turned you off? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it on the social platform of your choice. I love new readers!

I write science fiction, fantasy, and science fantasy. I also write about science fantasy, tabletop RPGs, books, culture, and more. If you want more content like this, check out my other blog posts and sign up for my newsletter.

October 26, 2023

Microblog: The Architecture of Reignition

One of the things I love about fantasy and sci-fi (and science fantasy) is how prominent a role setting plays in establishing the theme, tone, and feel of a story. Lord of the Rings would not be so magical without the sparkling waterfalls and leaf-shaped architecture of Rivendell, nor would Blade Runner feel so manic and oppressive without the towering neon billboards or the seemingly endless rain.

The setting of the story Reignition from my collection When Stars Move & Other Stories is the ancient city of Ith, a city that was intended to be as much a feature in the story as Karma and the Order of Uln. I set out to create a place that would make Karma, and by extension the reader, feel small, powerless, and insignificant. It is a city of machinery: hulking steam vents spill damp air, clattering funiculars are used to carry people up from the lowest levels of the city, while the wealthy race through the upper levels of the city in autocarriages. What room is there in such a place as this for a simple teenage girl?

Ith is built layer-upon-layer, with the poorest in the oldest, lowest levels and the wealthiest on top. I imagine a city built into a sort of ravine with each layer constructed atop the one beneath it, darkening the sky above. This layering was inspired by my visits to cities such as Valencia and Paris, place where you can literally descend below the surface of the city into layers below once inhabited by Visigoths and even beneath those layers, ruins left behind by Romans. Places where new layers are built atop the old, one after the other. The only difference in Ith is that the old layers remain in use. In Reignition, the layers of Ith are also representative of power and influence. Those who sit in the upper layers look down upon those below, quite literally!

These architectural elements come together to create a sense that Karma is powerless, that she is meant to be a victim of the world she was "reignited" into. And when she defies her superiors and seeks to uncover the truth, not only is she putting herself at risk, but she is standing up against a system that is literally built to oppress her.

If you haven't read Reignition, be sure to grab a copy of When Stars Move & Other Stories. And if you were fascinated by that world, you'll be delighted to learn that I have a whole novel set in Karma's world: Gods of Sky and Dust.

Be sure to sign up for my newsletter and follow me on socials to learn more about my writing and to be the first to hear when Gods of Sky and Dust is published!

October 19, 2023

On Space Wizards and Laser Swords

Online communities are filled with discussion of subgenres like the aptly-named romantacy and YA dystopia. So why is no one talking about the popularity of science fantasy, a subgenre that includes heavy hitters like Star Wars and Final Fantasy?

What We Talk About When We Talk About Space Wizards

What We Talk About When We Talk About Space WizardsIf we’re going to talk about science fantasy—and it’s a topic I love to talk about—we first have to define what it is.

Science fantasy is, as evidenced by the name of the subgenre, a story that includes both science fiction and fantasy elements. It’s a subgenre that may be nearly as old as science fiction itself, since the earliest authors didn’t discriminate in the same way many do today.

There are science fantasy stories that sit firmly in the middle—stories like Jack Vance’s Tales from the Dying Earth, or video games like Torment: Tides of Numenara, or even Star Wars. Then there are works that sit closer to the science fiction side or the fantasy side.

Dune is a classic example of the former. On the surface, it appears to be a science fiction story leaning hard into ecological sci-fi (one of the earliest books to do so), bioengineering, eugenics, space travel, and a rich and detailed history that has recognizable ties to our present world. But it also has mystical prophecies, the ability of the main character to foresee the future, superhuman powers gained by the spice mélange, and a feudalistic society that is reminiscent of much western fantasy.

On the example of a fantasy tinged with science fiction elements, we can look at the Final Fantasy series of video games. Each game in the series features magic powers, monsters, fantastic worlds, and prophecies—all classic tropes of fantasy. Some of the settings are medieval/feudalistic while others are futuristic or steampunk, however all of them feature a clear focus on fantasy elements. Prevalent in many of the games, however, are elements apparently plucked from science fiction: robots, giant machines, even cars and other technological vehicles.

Science Fantasy AscendantScience fantasy is more popular than ever, largely thanks to Star Wars, in my opinion. With mystical powers like the Force and literal laser-swords, Star Wars clearly includes a heavy dose of fantasy elements in with its X-Wings and Wookies.

The generation that grew up on Star Wars and Nintendo games, and passed that love onto their children, have turned our culture into one where science fantasy stories are as commonplace and popular as sitcoms and dramas.

It isn’t just Star Wars and Final Fantasy that have boosted the popularity of the subgenre. The release of the Dune: Part 1 film in 2021 was a triumph, finally bringing a classic science fantasy novel to the big screen in a way that succeeded commercially and culturally (unlike the flawed but fantastically stylized David Lynch film from 1984 or the sadly anaesthetised made-for-SyFy miniseries released in 2000). Dungeons & Dragons, which has distant roots in science fantasy, saw a huge boost in popularity with the onset of the Pandemic and the appearance of online virtual tabletops. The enormous popularity of comic book adaptations to film and TV should also count, since these stories commonly blend contemporary fantasy—superpowers—with common science fiction themes like invading aliens, time travel, and more.

Worlds of Robotic Sorcerers and AI DemigodsWhat draws me in most powerfully in science fantasy stories is always the worldbuilding. The way in which science fictional and fantastic elements are blended to create deep and rich worlds can be truly fascinating and original.

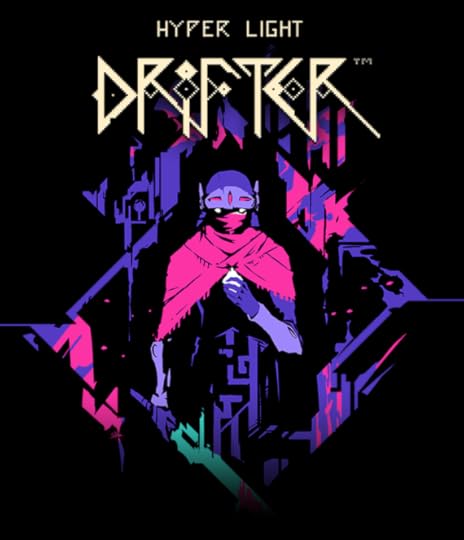

One great example is a little indie video game called Hyper Light Drifter released in 2016 by Heart Machine. It’s a 2d pixel-art action RPG influenced by early Zelda games with an incredible soundtrack by Disasterpeace. The protagonist is an energy-sword wielding hero suffering from an unknown disease of the heart. Controlled by you, they explore a world of ancient ruins, fallen giant robots, corrupted computers, and monoliths inscribed with forgotten languages that must be collected in order to progress through the game.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is a beautiful and haunting anime film released in 1984. It’s a tale of the dangers of the ravages of war and environmental catastrophe set thousands of years after a nuclear apocalypse, when civilization has reformed into small kingdoms like the Valley of the Wind and wild, dangerous places like the Toxic Forest.

The worldbuilding doesn’t get more elegant, fantastic, or dense than in Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun series, a quartet of novels set so far in the future that the sun will soon burn out and a new sun will be born. Wolfe, like Tolkien, invents his own language to describe this world in are unfathomably distant future, but he presents the world to us through a mysterious protagonist who rarely reveals the whole truth about his motives or intentions. I plan to cover this masterpiece in its own blog piece later this year.

In many of my favorite examples, it’s the sense of the passage of time that is the connecting thread.

Sprawling histories and lost secrets stretch out inside my imagination and fill it with ancient halls, corroded spaceships, and wars that upend entire worlds. It’s a theme that’s often present in my own science fantasy stories. In When Stars Move, Anusha finds a robot that’s been buried for a hundred years, the world passing it by from one day to the next. In my novel Gods of Sky and Dust, Varick and Anias go on a quest with another robot, Aion, to find out what happened to the vanished gods of their world, the Skylords. And in my current work-in-progress, The Radiant and the Corrupt, the catastrophe that unfolds in Inkosa’s life was set into motion with events that transpired on a distant planet more than two thousand years before her birth.

This fascination with ancient histories was born out of my interest in the history of our own world. Ancient civilizations that existed hundreds or even thousands of years ago died out and disappeared, leaving behind structures and ruins like the Colosseum, Machu Picchu, the Temple of Artemis, the Great Serpent Mound, Ephesus, and many more. Our planet is dotted with places like this where you can go and touch a distant, mysterious past with your own hands. Visiting such places begs a profound series of questions—what happened to those people? How did their civilization fall? How was our own born from that? Will our civilization one day collapse? And who or what will rise from its ashes to build something new?

The Question at HandAt the beginning of this blog, I posed the question, why is no one talking about science fantasy when it’s clearly so popular? I believe there are a variety of reasons.

First, the term “science fantasy” originally appeared in the 1940s in very pulpy, planetary romance-type stories (think Buck Rogers and Forbidden Planet). It carried a certain stigma that was hard to escape. Even fantasy authors carried this stigma that didn’t plague the more “serious” science fiction authors. The legendary Anne McCaffrey, for example, insisted on being called a science fiction writer even though her work clearly spans genres.

Fortunately, most of the genre bias distinction has faded (though it still exists—there remain readers who look down on genres they don’t read as somehow “inferior”), at least in terms of science fiction and fantasy.

In video games, where science fantasy is quite common, distinctions of narrative genre are largely unimportant. No one talks about Starcraft being a “science fiction” game or The Legend of Zelda being a “fantasy” game. Video games are categorized more by gameplay elements (real-time strategy, open world adventure, etc.) than by setting or narrative tropes, so the distinction of science fantasy is simply not remarked upon.

In the end, I suspect that the discussion of science fantasy is overlooked mostly because the subgenre has become so commonplace that it isn’t remarkable in its sudden popularity, as opposed to newer subgenres such as cozy fantasy or solarpunk.

I also think that the genre conventions of what makes something a “sci fi” story or a “fantasy” story are very blurry at the edges. Are psychic powers science fiction or fantasy? What about time travel? Laser swords? The fact is, science fantasy stories can almost always be considered science fiction or fantasy, and thus they are often lumped into the wider genres. We often have an intuitive sense, based on how we define our own ideas of genre, whether a narrative should be lumped into science fiction or fantasy. For stories like Foundation, it’s pretty easy to call it science fiction (though there are a few fantasy-like elements in there), and with works like Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light or Chronicles of Amber they’re largely considered fantasy, even though they contain varying degrees of SF elements. But some narratives, like Star Wars, sit firmly on the middle line and cause heated debates over whether they are science fiction or fantasy.

It comes down to how you personally define the genres and the bounds of the genres. But really, we need to acknowledge that there is a grey area, and that grey area is called science fantasy, and it’s an amazing playground that is worth exploring in fiction, comics, games, films, and TV.

What do you think? What are your favorite science fantasy narratives? Is Star Wars fantasy or science fiction? Add your thoughts to the comments below.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it on the social platform of your choice. I love new readers!

I write science fiction, fantasy, and science fantasy. I also write about science fantasy, tabletop RPGs, books, culture, and more. If you want more content like this, check out my other blog posts and sign up for my newsletter.

October 12, 2023

Microblog - The Cutting Room Floor

One of the toughest things to do in writing is cutting words you love and leaving them behind. When I undertook to restructure and rewrite my current work in progress, The Radiant and the Corrupt, I had to discard 4 entire chapters, some of which contained some very entertaining writing. Maybe some of these pieces will slip back into the final text in a different form, but for now I thought I'd share with you a brief scene that got left behind in the dank recesses of my hard drive.

It was best to be asleep when crossing a threshold, but sometimes that wasn’t an option. And sometimes you awoke during a crossing.

Once, when he was around ten years old, Gen had been very sick. Feverish for three days, they told him later. All he remembered was existing in a delirious fugue that seemed to go on endlessly. Waking and sleeping were inseparable. His whole universe was chills and body-aches and the spinning timelessness of senseless thoughts that ran loops around one another, starting where they began so that there was neither beginning nor end.

That was what crossing the threshold was like as Su Li carved a hole in reality and slipped out of it, passing into that other that existed outside the physical bounds of the universe, which was called the Unbounded Realm. It was a place of infinite space and time, of seething horror and transcendent beauty, a place where greater intelligences and outer gods who lacked form and agency within the physical bounds of the universe could subsume and consume infinite territory into their beings. It was an impossibility, and its impossibility dictated that things from the physical universe should not exist there. Could not exist there.

At least, not for very long.

Which was acceptable, since Su Li did not dwell in this otherness any longer than necessary to fully exit the physical universe. Using the same unfathomable machinery of her gate-drive, she carved a hole in unreality and slipped through, back into the physical universe, hundreds of light years from where they had existed only seconds before.

However, those few seconds existed only in the physical universe; time didn’t exist in the same sense in the Unbounded Realm, or at least it didn’t feel like it. Which is why laying in a passage creche, fully conscious, Gen found himself lost in a fugue of waking dreams, maddeningly imprecise and circular, each thought-form leading back into itself like a snake eating its own tail.

The ship…Su Li…the cave beneath…the Castle…subterranean floors hidden for a millennium…an oath…a screaming voice…a Spirit of Grace…blood dripping from a blade…passing through a doorway…flight…a doorway…a gateway…passage through a gate…a ship with a gatedrive…the ship…Su Li…the cave beneath…the Castle…

And so on, ad infinitum, until the madness was over. Visions without coherence but weighted with significance that left Gen inevitably saddened and confused by the sense that he had failed to grasp something important.

He sat up, sweating and shaking. He didn’t vomit anymore. He’d been through the experience enough times that his body was accustomed to it at least. He took a drink of water and wiped the sweat from his brow.

“Passage completed,” Su Li said. “Gateway closed. Welcome to Lhusan.”

Thanks for reading! If you like weird stories of talking spaceships and dead gods, be sure to sign up for my newsletter. And if you like this excerpt, please share it on social media!

September 27, 2023

Microblog - The World of Anusha & Stan

With the release of the print version of When Stars Move & Other Stories, there's been a renewed interest from readers in the title story. This is a setting and characters I hope to return to one day, and I've outlined more stories with them. ell me more about Anusha and Stan, you cry. Well, without further ado, here is some lore about the setting of When Stars Move.

The world is a magical place!

The world is a magical place!In the world in which Anusha and Stan live, not only is magic a real force, but the stars in the sky literally move. There are three major regions featured in the world of Anusha and Stan, each with their own magic. And each of the cultures of these regions interpret the significance of the movement of the stars in different ways.

Tyros is where Stan was forged (in a manufactory called "Standard Engineering Works"). The Tyrosi are masters of engineering and trade and have learned the secrets of infusing arcane energy into machines to give them life and even sentience. In Tyros, each family believes its fate is tied to that of a star; the position of the stars influences how different families rise or fall in political and social significance within the society. They are led by the Polemarch Alexandr II.

The Sultanate of Arak is known for its mastery of alchemy as well as its fine fabric crafts. Arak is a monotheistic theocracy in which the priesthood is influential, able to influence even powerful Sultans such as Anusha's father. This power is derived from the astronomer-priests, a caste who specialize in reading the position of the stars which they interpret as the word of God. Through such pronouncements, they wield spiritual as well as political influence in Arak.

Finally, there is the Middle Kingdom, a setting not featured in When Stars Move. The Middle Kingdom consists of dozens of providences that fall under the sway of the Imperial Bureaucracy, led by the Immortal Emperor. The emperor is centuries old, kept "alive" through ancient sorceries and alchemical elixirs imported from Arak. The providences are home to nature spirits and hungry ghosts. In the Middle Kingdom, scholars and hermits see the spirits of the Celestial Court in the movement of the stars, using their movements as a method to predict the future. But the viziers with true power and influence ignore the warnings and pronouncements of the shamans from distant villages.

This is the world in which Anusha and Stan inhabit! One day, maybe you'll see their journey from Arak to the Middle Kingdom in search of a home where they can be free, only to get caught between imperial politics and the fate of the entire world!

September 20, 2023

Science Fantasy - Tales of the Dying Earth

A faded red sun fills the sky...Ancient ruins sparkle and groan in a muted landscape...Forbidden and forgotten technology lies hidden deep in underground tombs...Wizards channel magic through intense concentration and arcane utterances...This is Jack Vance's Tales of the Dying Earth

The namesake of the "Dying Earth" subgenre, Tales of the Dying Earth is one of the most important influences in the science fantasy genre.

This volume is actually a collection of four short "Dying Earth" books. The first, The Dying Earth, was published in 1950. The Eyes of the Overworld, the second volume, was published in 1966. The final two volumes, Cugel's Saga and Rhialto the Marvelous were first published in 1983 and 1984, respectively. Now, these four works are generally collected together in a single volume.

The earlier works are considered "fix-ups," or novels comprised of interconnected short stories, while Cugel’s Saga and Rhialto the Marvelous contain longer stories that one could consider proper novels.

The Dying Earth stories are set in the far-distant future Earth, at a point where our sun is nearly burned out, the moon is gone and magic has become a force that exists in the world. Civilization has fallen to ruin and monsters roam the land. The characters wrestle with strange powers and stumble upon bizarre technology from ages past.

Jack Vance isn’t the first author to write stories set so far in the future that the sun is burning out and our civilization is long turned to dust, but his work did name the subgenre. Earlier far future “dying earth” stories include works by Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, and H.G. Wells, among others.

StyleNotably, Dying Earth stories are different from apocalyptic stories. Apocalyptic stories deal with the threat of individual and societal survival in the face of catastrophe. Dying Earth stories, by comparison, exist so far in the future that our current history is lost to the dust of time.

In Dying Earth stories, the setting establishes the tone and style – sort of romantic, melancholy, strange, and esoteric.

The wizards of Grand Motholam fled like beetles under a strong light; the lore was dispersed and forgotten, until now, at this dim time, with the sun dark, wilderness obscuring Ascolais, and the white city Kaiin half in ruins, only a few more than a hundred spells remained to the knowledge of man. Of these, Mazirian had access to seventy-three, and gradually, by stratagem and negotiation, was securing the others. - Jack Vance, ,Tales of the Dying Earth

Jack Vance is a master of this tone. His writing is descriptive and evocative. The characters and the plots reinforce the themes of civilization crumbling, of history being lost to time.

Vance’s prose is interesting, painting these elaborate, detailed scenes but populating them with shallow, facile characters who are far more interested in their own selfish lives than in the rich history that surrounds them.

“I categorically declare first my absolute innocence, second my lack of criminal intent, and third my effusive apologies.”- Jack Vance, ,Tales of the Dying EarthInfluences

Vance's Dying Earth stories were hugely influential. In terms of obvious major influences, the most immediate comparison can be made to Gene Wolfe's masterpiece, ,The Book of the New Sun, which I hope to cover in a future blog post. Many of the ideas birthed by Vance are nurtured and brought to maturity by Wolfe. But Gene Wolfe is far from the only major author to be influenced by Jack Vance. Michael Chabon and Dan Simmons both count him as an influence as well.

For a more popular influence, we only need to look at Dungeons and Dragons. In D&D, wizards learn magic by studying ancient tomes. This is done by spending hours each day memorizing esoteric phrases and gestures. A wizard can only memorize a certain number of magical spells per day varying by their level of mastery and doing so takes intense levels of concentration. Once the wizards casts a spell, it is wiped from their memory. The wizard can only cast the spell again after resting and spending more time imprinting the details of the spell into their mind once again.

This system, first invented by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in the very first edition of Dungeons & Dragons, is lifted straight from Vance’s Dying Earth stories. It’s even known as “Vancian magic” because that's how Jack Vance described wizards and their magic.

The Numenara tabletop role-playing game from Monte Cook Games, which is also the featured in the video game Torment: Tides of Numenara, is heavily influenced by the Dying Earth stories of Jack Vance. One of the notable likenesses is the ways that ancient technological artifacts are used like magic.

My ThoughtsThese are not the most sophisticated stories, but they can be a lot of fun to read if you know what to expect. They’re adventure stories if you boil them down. They’re about thieves and outcasts searching ancient ruins, stumbling upon a wizard’s lair, and trying to escape unscathed.

Vance presents a mystical, mysterious world, and you can just see the edges of our own history sometimes peeking out from underneath, making you the reader feel like you know more secrets than the characters do.

I think that’s one of the fun things about Dying Earth stories, is seeking the connections between this strange future and the one we live in now.

It's worth being aware, too, that these stories are products of their time and thus contain stereotypes that wouldn't fly today. Female characters are underdeveloped or objectified, something unfortunately common at the time. And the character development in these stories is lacking – particularly the earlier stories are primarily pulp adventure yarns that feel more contemporaneous with Edgar Rice Burroughs or E.E. Doc Smith.

Borrowing IdeasTales of the Dying Earth is a goldmine of ideas for authors, GMs, players, and other creatives who like science fantasy.

Cugel the antihero is a model for an interesting main character or player character in a TTRPG. He thinks highly of himself but he is truly a scoundrel, selfish, short-sighted and greedy. It is only by his luck and wits that he gets out of situations. A sort of proto han-solo in a fantasy setting, Cugel stumbles from one adventure to another, finding himself deeper in trouble each time.

Unique cultures – Vance fills the Dying Earth stories with a seemingly endless variety of cultures. Each place seems to have its own strange religion, legal system, economy, and social and cultural practices. Any one of these could be the setting of a story or book; Vance crams them all together to make something truly strange. As a worldbuilder or game master, there are literally dozens of setting ideas here for the borrowing.

Magic as strange and powerful – Too often in fantasy stories, we see magic painted in one of two ways – either magic is a system operating under detailed rules, as seen in Brandon Sanderson’s books, or magic is an unknowable, mystical theme that serves the whims of the story, as in fairy tales or Miyazaki films. Vance presents something different – a powerful force that is inexplicable but nevertheless that selfish, power-hungry men seek to exert control over. One could conceive it as a metaphor of humankind trying to exert control over nature, but setting this aside, the idea of magic as a force that is beyond control or understanding is a compelling and exciting one that could make its way into any number of stories or games.

ConclusionJack Vance’s Tales of the Dying Earth is one of the most influential collections in the dying earth subgenre, and an important book in the genre of science fantasy. If you love adventure stories, or if you are just interested in experiencing the roots of the dying earth subgenre, it’s a collection worth checking out. However, the stories are pretty simplistic and the writing suffers from some outdated stereotypes and ideas. If this is a big turn-off for you, you might not want to spend your time trying to get into this.

If you like science fantasy, consider checking out one of my books. When Stars Move & Other Stories contains a science fantasy story called "Reignition" in which the main character is brought back to life using esoteric technology to serve the cult of the god of the dead. I expanded that setting into what would become a full length novel, the as-yet-unpublished Gods of Sky and Dust.

If you are interested in science fantasy, writing, games, or worldbuilding, you've come to the right place! Be sure to sign up for my newsletter for more.

Finally, share your thoughts in the comments! What do you think about Jack Vance's stories? What are your favorite science fantasy books, movies, or games?

July 18, 2023

DMing Dragon of Icespire Peak

This blog series teaches new and returning Dungeon Masters how to run the Dragon of Icespire Peak Campaign from the D&D Essentials Kit and provides advice and guidance for being an effective DM. Check out Part 1 of this series here.

Campaign Structure and Main Story

Campaign Structure and Main StoryBy now, you hopefully have a group of players, you’ve read over the adventure, and you’ve run or are about to run your Session 0. Which means you hopefully have a decent idea of what kind of characters your players want to run and what their backgrounds are going to be. Now it’s time to start planning out your first adventure and thinking about the broader campaign!

In Dragon of Icespire Peak, the party arrives in the town of Phandalin which has recently come under threat from a white dragon that has taken up residence in the nearby mountains. The arrival of this dragon has disrupted monsters and factions in the region, causing a bunch of problems to crop up, which the characters will deal with as individual quests.

There is a local “job board” which displays up to three quests at a time. The party gets to select which quest they will pursue, which then takes you to a different location in the region. This presents the central structure of the campaign – choose a job from the board, complete it, return to collect a reward, and select a new quest. There are three tiers of quests – as the party completes the earlier quests and gain levels, the second tier of quests become available. These quests are more challenging but offer bigger rewards. Finally, a third tier of quests becomes available. Then as the culmination of the adventure, the party will face down the dragon, Cryovain.

The job board format presents a nice structure around which to run a new campaign. It presents bite-sized quests that are easy to tackle and digest. As the DM, you only have to prep a single quest at a time. And the players only have to figure out how to clear the monsters out of the local mines or deal with a marauding manticore rather than figuring out all the steps needed to stop an evil demigod from taking over the world. The job board format also offers the players a lot of agency – the party gets to choose what direction the story goes within the framework of a few options. They are less likely to feel “railroaded” into one choice, but their choices aren’t infinite, either.

However, the biggest weakness of this structure is that there really isn’t much of an overarching story. Cryovain is a distant threat – it’s not like the dragon is actively plotting to take over the town. The various quests individually are interesting but are largely disconnected from one another. This leaves the campaign without a strong narrative thread, which, depending on what kind of game you envision running, might leave you a little bit dissatisfied.

...the biggest weakness of this structure is that there really isn’t much of an overarching story. Cryovain is a distant threat...

Fortunately, you’ve found this blog. Here, you’re going to learn how to incorporate a strong central narrative into the Dragon of Icespire Peak Campaign while still leveraging all the good structural stuff that’s already there, like player choice, the job board, and fun adventures. Strap in, cause you're about to learn how to invent a story out of thin air.

Narrative of Icespire PeakThere are three ways you can layer in a narrative to Dragon of Icespire Peak. I encourage you to consider all three approaches if you want to have a memorable and dramatic campaign story. But you don’t have to – you can stick with just one approach (or none, if you’re satisfied running the module as-written).

Leverage Character BackgroundsThis is my favorite approach to creating story because you don’t have to do the work! The players have done most of the heavy lifting for you. They’ve told you what kind of story they want to experience – they even wrote it down on their character sheets!

You remember that Session 0, right? The one where you asked each of the players to come up with a background and a reason for why their character is in Phandalin? It’s time to put that background to work.

Review the characters’ backgrounds and reasons for traveling to Phandalin and the Sword Coast. Then look over the quests in the campaign as well as the characters, deities, factions, and areas referenced in campaign. Look for connections, even if they are close. Once you spot one, think about how the character’s background or reason could tie directly to that element of the campaign in a way that presents a problem for the character to solve.

Some possible connection points include: the Harpers, the Zhentarim, the religions of Talos, Tymora, Savras, or Chauntea, the various townsfolk, Lord Neverember, and more!

For example, suppose one of the characters is searching for a lost sibling who was last seen in the Phandalin region. The character is likely to ask around town to see if anyone has seen this person. You don’t want to let them resolve the situation immediately, because that wouldn’t be very interesting – instead, you want to present problems the character must overcome in order to find the missing sibling. Maybe a diplomacy or investigation check might reveal that the sibling was in town a few weeks ago but left with a trade caravan some time back. The caravan is due back in Phandalin in a week’s time.

Now the PC has a reason to stay in or around Phandalin. You have just taken the first step of connecting the character to the adventure and the town.

To continue the example, suppose after the characters complete a couple of quests (and level up), the trade caravan returns to Phandalin. It turns out that the sibling traveled with the caravan to Falcon’s Hunting Lodge (an important location in the campaign). And conveniently, there is also a quest on the job board to go to Falcon’s Hunting Lodge. And so on, until you reach a point where the character finally rescues their missing sibling from the clutches of some evil half-orc cultists or a white dragon.

Importantly, you don’t need to figure out all the details of this character-specific quest now. Just find the initial hook or connection point and go from there.

One caveat: some players may not bother to come up with important background quests. They might just have traveled to Phandalin for fame and glory. This is fine! Some players have more fun discovering what’s important to their characters as they play. But if you’re spending time focused on those PCs who have well-developed backstories or compelling connection points, the players who are just there for adventure might feel left out. Therefore, it’s important to develop situations, problems, even quests where their characters can play a significant role. See below for ways you might make this happen.

For more on factions in the region and other potential connection points to the character backgrounds, check out the Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide published by Wizards of the Coast.

Develop the TownsfolkAs-written, Phandalin is a pretty dull place. All the of the NPCs presented in the story are flat, one-dimensional characters. Each of them exists only to relate “tales” to the characters that point them towards side quests that may not show up on the town board, or to sell them things.

The two most interesting characters as-written, are Townmaster Harbin Wester, who has become a shut-in, and Halia Thornton, who runs the miner’s exchange and who is only interesting because she’s an agent of the Zhentarim who, according to the campaign guide is “working slowly to bring Phandalin under her control.” Unfortunately, we never hear another iota about her.

Whether or not you choose to build quests around these characters, I’m going to strongly encourage you to take a little bit of time to flesh out the NPCs in town a little bit more. The PCs are going to spend a lot of time in Phandalin, talking to NPCs, and you’ll have a lot more fun roleplaying if those townsfolk have some personality and their own agendas.

Therefore, I highly recommend you make a few notes about each NPC the party is likely encounter. I want you to come up with three traits: what is one thing that the character wants? What is one interesting personality characteristic? And how does this person feel about outside adventurers? That last trait is interesting because it is likely to evolve over the course of the campaign.

Simply answering these three questions for the named NPCs in town is likely to give you a lot more to go on both in connecting to characters’ backstories as well as in establishing narrative tension.

Let’s go back to Halia Thorton. An agent of the Zhentarim, you say? Those are bad guys! She could recruit the players and turn them into allies, only for them to discover later they’ve been working to advance an evil agenda. Or they could discover exactly how Halia Thorton is trying to take over the town (and who in town is trying to stop her).

Again, as you’re thinking through these narrative ideas, look for ways they might connect to the existing locations in the adventure. Maybe she’s trying to take over all the gold mines in the region and so wants the party’s help in securing some of the locations.

In any case, having some interesting characters who want different things and who may even be opposed to one another will create lines of tension in Phandalin. Some NPCs will become the party’s allies, some will become enemies.

Critically, you don’t need to answer all these questions at the outset. Just answer the three questions about each character: what do they want, what’s one personality characteristic, and how do they feel about outside adventurers. Then, once you start playing and the PCs begin interacting with these characters, you’ll have some guidelines on how to react and how to roleplay them. The players will find them to be interesting and will naturally begin to develop feelings about them – maybe they really like Toblen Stonehill but come to distrust Harbin Wester and his insistence on hiding in the Townmaster’s Hall. What’s behind that door he hides behind, anyway? Just like with backgrounds, you’re letting the players do most of the work here. Let them clue you in on what they find interesting. Then you can flesh out those characters and their problems more as the campaign develops.

If you want some additional background on the NPCs, check out the Lost Mines of Phadelver campaign from the original D&D Starter Set, which talks more about some of the NPCs in Phandalin. You may have access to it as part of your D&D Beyond account if you have one – it was free there for a while.

Threaten Phandalin

You won’t want to do too much with this at the beginning of the campaign, because an immediate threat to the survival of the town is something that first or second-level characters won’t be able to deal with. But it’s important to start thinking about this because this is really what the dragon is – an outside threat to the town.

You might choose to have other threats, chiefly because there’s no particularly strong reason for the dragon to be the central villain (the “big bad evil guy” or BBEG, in some parlance) of the campaign.

Thanks to the fact that you spent time to flesh out the NPCs, the PCs are going to develop relationships over the course of the campaign. They’ll have some NPCs they care deeply about, some who they see as enemies, and some who are simply useful allies. You’re going to leverage these feelings later in the campaign by threatening Phandalin, either with the dragon or with some other threat.

Presenting a direct threat to Phandalin brings a crisis to the campaign that it is lacking. The players arrive in this rustic mining town and do a bunch of quests to help out, but to what end? Developing relationships in town and then protecting the town from an existential threat is a compelling, gripping climax that will leave the PCs feeling like the heroes of Phandalin and will give the players a well-deserved sense of accomplishment.

Again, you don’t need to figure this out now, but rather just know that there will be an existential threat to the town, and you should start looking for it as the campaign progresses. Maybe Cryovain is going to decide that Phandalin is too much of an annoyance and it’s going to come attempt to destroy the town or kill some important townsfolk. Maybe the Zhentarim decide Halia Thornton isn’t doing enough and it’s time to take a firmer hand. Maybe the Talos Anchorites that keep popping up have organized the orcs and ogres in the region and launch a full-scale assault on the town with the aid of the Talos Avatar Gorthok.

See what develops. See what the PCs focus on. And look for opportunities to make connections to the existing campaign quests. Whatever this existential threat is, connecting it to other quests in the campaign will help to ensure that those quests feel meaningful and important in the long run, rather than just busy-work.

Considering Cryovain

Considering CryovainThe Young White Dragon Cryovain is presented as a central villain in the campaign, but the most story we get is the idea that the arrival of the dragon has disturbed other monsters in the region and that’s why all these quests are popping up. The campaign presents a random chart for locations where Cryovain may pop up.

This is a nice idea, but never ensures that the PCs will encounter Cryovain. Instead, I recommend that you use some narrative tricks to make Cryovain feel like a threat. Every couple of adventures, make sure the PC’s are finding evidence of the threat that Cryovain presents. Maybe they come across the frozen carcass of a half-eaten owlbear. Maybe they pass by a farmhouse that’s been destroyed, the people missing. Maybe they see the beast from a distance. Maybe while they’re camping, the dragon passes overhead, chilling everyone with dragon fear.

Keeping the dragon present ensures that no one ever forgets – there’s a big ass monster out there and it’s making problems!

Starting the AdventureFor the first adventure, work with the players to figure out how the characters arrived in Phandalin and if they know each other. For my campaign, we decided that the PCs were working as caravan guards on a supply caravan coming from Neverwinter. We even had giant spiders attack the caravan before we reached Phandalin, giving the party an opportunity to test out their skills in combat.

Once in Phandalin, give the PCs an overview of the town and its key locations. Allow them to interact a bit with the different NPCs and pay attention to who they connect to. Make sure to point out the job board and the starting quest(s) attached to it.

One thing I would recommend doing is having the different NPCs in town talk about the specific quests associated with the job board. For example, if the PCs ask around about buying healing potions, you could reveal that the herbalist and midwife Adabra Gwynn lives on Umbridge Hill, but she hasn’t been back to town for a while. The Townmaster has even posted a reward for someone willing to go check on her. Or perhaps Toblen Stonehill mentions over a mug of ale about the two treasure-hunting dwarves Dazlyn and Norbus who went looking for an old excavation, suggesting greedily that if the pair “disappeared,” the ruins they went to claim would be up for grabs.

The townsfolk can even talk about characters or threats from other quests that won’t appear on the job board until later, such as referencing orc raiders or marauding wererats. As mentioned, the module offers you rumors that you can roll randomly, and these can be useful later in the module to signal specific locations you want the characters to visit, but I like to make it feel more organic than a random roll.

By presenting the quests not just with signs on a job board, but with connections to the townsfolk, you will begin to make the PCs feel invested in the quests and the town of Phandalin and you’ll start to make Phandalin feel like a real place rather than a video game quest hub.

Suggestion: Start with a Single QuestOne of the biggest hurdles with starting to run Dragon of Icespire Peak as a DM is that you have to do all this reading and prepping the townsfolk, and then, because there are three possible quests the PCs can choose from, you have to be prepared to run any one of the three. You don’t want the players looking at the quests on the board and saying, “Let’s do this gnome thing” and you have to say “Sorry gang, I didn’t prep that one. Can you pick one of the others instead?”

So, if you want to make life a little easier on yourself, don’t put all three quests on the board at once. Just put one there! You can still have the townsfolk talk about the other quests, then when the PCs return from the first adventure, they’ll see the quest and they’ll remember the NPC mentioning something about that, which makes you look really, really clever! And then you only have to prep a single quest, and because it’s the first adventure and the players don’t really know what it’s about yet, they won’t feel railroaded. Instead, they’ll feel like they’re taking the hook and seeing where it leads.

Which is exactly how this campaign should feel.

One Final NoteRemember, the PCs are still only first level. They are squishier than a rotten kobold. A single solid hit or a crit from a monster is likely down them or possibly kill them. I’m not going to tell you to fudge rolls – how you handle stuff like that is down to part of your DMing style, and it’s something you need to figure out with your party. BUT, it’s worth knowing how lethal the starter adventures are and thinking about some ways of managing the threat a little.

The PCs are squishier than a rotten kobold.

For the Umbrage Hill quest, the manticore is a really challenging fight for first level characters, especially given that the beast can fly and gets multiattack. It also has a solid attack roll bonus, a fat bag of hit points, and does decent damage. It can definitely kill a first-level character or two before it gets taken down.

The adventure notes that the manticore was driven from its home by Cryovain and that the party can negotiate with it. The monster stat block indicates that the creature is intelligent and speaks Common. You can prompt this idea of negotiation by having the manticore talking when the PCs arrive at the location. It can be outside, threatening Adabra Gwynn and telling her how hungry it is and how it would satisfied with just a leg. This could prompt the PCs to negotiate with it or threaten it, perhaps bribing it with some rations or making a deal to hunt down another animal.

Alternately, you could have the monster simply fly off when threatened. You can describe the beast as looking particularly scrawny and hungry, or wounded from a prior battle. When the PCs engage, don’t make the manticore fight to the death. Instead, once the creature reaches half or fewer hit points, have it fly away, maybe sending a spray of tail spikes at them as it departs. This is the sensible way for the monster to behave anyways. (It’s not like fighting to the death is a great idea when you’re losing!)

For the Dwarven Excavation quest, it’s worth noting that ochre jellies are immune to slashing damage. The first time a PC hits it with a slashing weapon, be sure to use the creature’s Split ability and be sure to indicate that the attack didn’t seem to deal any damage. I would recommend that wherever the PCs encounter the ochre jellies, that you indicate there are a couple of old clubs, staves, or other blunt weapons lying about.

You may also want to clue the PCs into the fact that the ochre jellies are very slow. A clever party will quickly realize that they can simply stay out of the monsters’ movement zone and attack them with ranged attacks and spells.

Also, look out for that explosive trap. If multiple PCs are downed, rather than kill them, just rule that they are knocked unconscious and the dwarves Dazlyn and Norbus dragged them out of the ruin after hearing the explosion. This now presents a new narrative opportunity as it puts the PCs in the dwarves’ debt.

Back to PhandalinOnce the PCs have completed the first quest, they’ll likely return to Phandalin to collect their reward. Be sure to indicate what quests are on the board and try to get a sense from them of which quest they’d like to tackle next. This will give them a sense of choice but also by having them pick the quest before you end the first session, you will know which quest to prepare for the next session!

That’s a Wrap!

You did it, you’ve run your first adventure and begun the Dragon of Icespire Peak Campaign. Feel good about yourself! You have taken the first step on a grand adventure and you’ve already accomplished the most difficult part… you got started.

More ResourcesThere are some terrific guides out there on Dragon of Icespire Peak, including some great advice for specific adventures. Additionally, the Dragon of Icespire Peak subreddit has lots of great discussion, tips, and resources for quests that you can take advantage of. Here are a few links I recommend you check out.

Running Dragon of Icespire Peak from the D&D Essentials Kit | Sly Flourish Dragon of Icespire Peak DM Guides | Bob World Builder Dragon of Icespire Peak SubredditFinal Thoughts

How did your first session go? Do you have questions about how to handle specific encounters? Advice for other DMs? Post your questions, thoughts, and feedback in the comments below.

If you like this article, please share it with your friends and subscribe to my newsletter at https://www.shannonrampe.com/.

April 22, 2023

Dungeon Mastering Dragon of Icespire Peak

This series is intended to introduce running Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) games as a new or returning Dungeon Master (DM) through the Dragon of Icespire Peak campaign provided in the D&D Essentials Kit.

Whether you’re preparing to be a DM for the first time, someone who wants to one day become a DM, are someone (like me) who returned to the DM Screen after many years, or just a DM looking for advice on running the Icespire Peak campaign, this blog series is for you!

Throughout the series, I’ll present tips for planning, expanding, and running the campaign. I’ll have campaign-specific advice and also best practices and suggestions on being the best DM you can be. Every DM has a different style, so not all of my suggestions will work for you, but it’s my hope that every DM who reads this series can take something away from it. This series is principally written for those playing in person, but most of this guidance applies to games run online using a virtual tabletop (VTT) as well.

If you enjoy this blog, please consider subscribing to my newsletter to learn more about my writing. You can support me by sharing my work or by purchasing one of my short story collections, both available on Amazon Kindle.

Getting Ready to Be a DM

Getting Ready to Be a DMWhat You Need to Know

If you’ve decided to take on the role of DM, chances are it’s because you love creating stories and worlds. Maybe you’ve been enchanted by the way another DM wove a story in a game you played in, and you wondered, “I wonder if I can do that?” The answer is, of course you can!

You might assume that, to get started, you need dice (true), players (true), an adventure (true, but you can make one on your own if you like), and a complete and comprehensive knowledge of the rules of Dungeons and Dragons (hint: this is the false one).

In fact, very few DMs are true masters of the rules. Instead, we become really good at adjudicating situations within a loose framework. You can always look up the correct ruling later, but it’s more important to keep the game flowing than to look up every single rule at the table. This ability to adjudicate on the fly is actually BETTER than knowing all the rules, because there are situations that will inevitably arise in your games where there exist no formal rules for how to handle, and being able to improvise a ruling on the fly will show your players that you are truly master of the game.

Here’s a list of the things you actually need to understand, all of which are covered in the basic rules:

How attack rolls, ability checks, and saving throws work How Advantage and Disadvantage work What a difficulty class (DC) is, and the difference between DCs (hint, easy = 10, moderate = 15, difficult = 20, adjust to your liking) How to read a monster stat block How to create a character (you won’t need to create one, but your players will, and it helps if you can answer questions)In addition to these rules, there’s an excellent section of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, Chapter 8: Running the Game, which has some solid advice. However, most of it is very situational. Still, I do recommend reading the sections on Table Rules, Rolling the Dice, and Using Ability Scores. These sections together will teach you a lot about adjudicating situations when you don’t know the actual rule.

How to Find Players

While it is possible to play solo, D&D is best as a social experience, so you’re going to need to find players. If you already have players, great! If you want to put together a group, here’s an article I wrote on how to do it.

There is lots of good advice on running great D&D games on SlyFlourish.com, but one I’ll point out here is an article on finding and maintaining a D&D group: https://slyflourish.com/finding_players.html

Choosing an Adventure

We’re assuming for this series that you’re planning to run Dragon of Icespire Peak from the D&D Essentials Kit, which we’ll talk about more, below. However, you can also create your own adventures. Check out this great video from Matt Colville on running your first adventure.

Like me, you may have chosen the D&D Essentials Kit and the Dragon of Icespire Peak campaign because the idea of building your own adventures sounded too time consuming or overwhelming. And what I will share with you is that both creating your own adventure and running a published adventure both require some work, but of slightly different types, and both approaches can be fun and don’t have to be too time-consuming.

The focus of this blog series will be specifically on using Dragon of Icespire Peak, but I will be suggesting a lot of ways to customize the campaign and make it your own, so I would still encourage you to check out that Matt Colville video as well as any of a number of articles on Sly Flourish’s website.

Planning the CampaignDragon of Icespire Peak is a relatively short campaign that will take characters from level 1 to level 6 or 7 and can be completed in 4-6 months depending on your play frequency and other factors. Our group had 6 players, we played 3 hours a week and the campaign took us just under 5 months to complete. The campaign is set in the Forgotten Realms, setting of the recent Dungeons & Dragons movie, many popular novels by R.A. Salvatore and other authors, as well as many well-known video games such as the Baldur’s Gate series. If you don’t know anything about the Forgotten Realms, it’s not a problem, but there are some factions you can leverage the flesh out your campaign if you don’t mind doing a little Googling or checking out the Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide.

The campaign is set in the mining town of Phandalin near the Sword Coast. It’s the same setting as the shorter introductory campaign Lost Mines of Phandelver. In Dragon of Icespire Peak, a white dragon has recently moved into the region, and it’s causing all sorts of problems and, surprise, the town is in need of adventurers to help solve local problems. On top of this, worshippers of Talos, god of storms and destruction, are causing problems in the region. The campaign is made up of a bunch of short adventures, some of which are connected and some are not. Characters will complete quests for the town before ultimately having to deal with Cryovain, the white dragon, and this campaign’s big bad evil guy (BBEG).

You should read the section on Running the Adventure and I also recommend skimming the Location Overview for each adventure just to familiarize yourself with the campaign. You don’t need to read each adventure in detail at this point. We’ll do a deeper dive into the structure and content of the campaign in the next article for this series, but up front it’s important to consider some the bigger picture question: what kind of game do you want to run?

To answer this question, you should jot down some notes to yourself to answer the following questions:

Do you want to run a game that is more gritty and feels like the stakes are high? Or will it be more lighthearted? What kinds of play do you want at the table? What is off limits? It is more important to have a satisfying narrative arc or for the players to feel like the world is realistic? Or somewhere in the middle? When are you willing to “fudge” a die roll? Are there any house rules you want to adopt? Any specific rules around character creation?It’s helpful if players create characters who would want to get involved in the campaign you’re running, rather than characters who have nothing to do with the world. (For example, if one of your players creates a character whose heart is set on traveling the planes, they have no real reason or motive to participate in this campaign.) So it’s vital that you tell the players what the campaign is about. You’ll do this by creating a 1-page Campaign Overview.