David Wilson's Blog, page 2

March 16, 2018

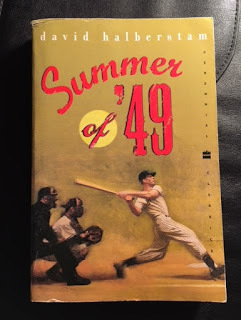

Halberstam captures the spirit of baseball from days gone by

BASEBALL

Baseball notes: Organizing a future column

by David Wilson

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Halberstam wrote several books that chronicled major events in America.

He was, in my mind, an artist that used words and stories rather than paint. And he put his work, not on canvas, but on the backdrop of history.

In two of his books (Summer of ’49 and October 1964) Halberstam does an excellent job of capturing the passion and pageantry of baseball, and in doing so he held up a photograph so that America could see what she looked like years ago. In 1949 the race to get to the World Series went down to the wire in both the American League and the National League.

Halberstam’s book begins: “In the years immediately following World War II, professional baseball mesmerized the American people as it never had before and never would again. Baseball, more than almost anything else, seemed to symbolize normalcy and a return to life in America as it had been before Pearl Harbor.”

The summer of 1949 was indeed amazing, as races in both leagues went down to the final day of the season.

In the American League, the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees fought it out for the pennant. In the National League, the heated competition was between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals.

The symmetry between the two leagues was amazing and Halberstam vividly provided the details.

In the end, in the American League the Yankees took first place with a 97-57 record. Boston was the closest second it could possibly be, with a 96-58 mark.

In the National League the numbers were the same. Brooklyn was 97-57. The Cardinals were second at 96-58.

So the Dodgers and Yankees made the Series an entirely New York affair, as they had done twice before, and as they would do four more times during the 1950s.

In his book October 1964, Halberstam tells of how the Yankees, at the end of their mid-century dynasty, met the up-and-coming St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series. Halberstam took a deep look in to the lives of players like Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Curt Flood, and simultaneously examined the social problems that they and all of America faced at that time.

For the baseball fan who likes to read, Halberstam has to be on your shelf.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on March 16, 2018 18:41

March 10, 2018

Baseball excerpt from the book Learning Every Day

BASEBALL

Learning Every Day has a section of insights and reflections from sports, with much to say about baseball. Here is an excerpt from page 76:

"I have always appreciated how baseball is interwoven in our country's history and culture.

To learn about baseball--its origins, its players, and the great cities that have served as baseball's stage--is to learn about America."

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Learning Every Day has a section of insights and reflections from sports, with much to say about baseball. Here is an excerpt from page 76:

"I have always appreciated how baseball is interwoven in our country's history and culture.

To learn about baseball--its origins, its players, and the great cities that have served as baseball's stage--is to learn about America."

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on March 10, 2018 06:59

Viewing baseball from the heart of the country

BASEBALL

Traditionally, if a person liked baseball and grew up in Arkansas, it was hard not to follow the Cardinals. This piece was originally published in newspapers on May 11, 2016

by David Wilson

St. Louis Cardinal baseball, over the course of its 124-year history, has developed a strong regional appeal that stretches in several states in the central part of the country, including Arkansas.

Part of the reason for that development is that in the earliest decades of major league baseball, St. Louis, as the westernmost team, was geographically situated to capture the attention of most of the Midwest.

It is understood that there is a growing interest in Northwest Arkansas with the Kansas City Royals, especially with their success in recent years, but the Cardinals simply have a longer relationship with Arkansans.

I grew up in Northeast Arkansas, where I learned of Cardinal baseball at a very young age by listening to Jack Buck, Harry Caray, (and later Mike Shannon) do the radio broadcasts of the games. I was probably three years old when I first remember hearing their voices give the count of balls and strikes on summer evenings.

My dad had the radio tuned to the Cardinal games because it was something he began as a boy living in rural Arkansas in the 1940s.

"We shelled beans and peas and listened to the ball game in the evening," my dad said. "We couldn't go to bed until all the beans and peas were shelled. We listened to Gabby Street and Harry Caray do the games. Gabby Street was the one they called 'The Old Sarge.'"

But my dad wasn't among the first in Arkansas to grow up listening to Cardinal broadcasts. In fact, it began as early as the 1920s when people started getting electricity and their first radio.

As far as Arkansas was concerned the Cardinals were not just the only game in town but the only game in the region.

Two different books by John Grisham (A Painted House and Calico Joe) provide insight in to how people in Arkansas followed the Cardinals and all of Major League Baseball during those decades.

A Painted House opens this way: "It was a Wednesday, early in September 1952. The Cardinals were five games behind the Dodgers with three weeks to go, and the season looked hopeless. The cotton, however, was waist-high to my father, over my head, and he and my grandfather could be heard before supper whispering words that were seldom heard. It could be a 'good crop.' ''

Calico Joe was about a young baseball player from the town of Calico Rock in north central Arkansas. He made a tremendous impact as a rookie with the Chicago Cubs and one of the subplots was how the people in Calico Rock and the surrounding area had trouble rooting for the Cubs when their hearts were always with the Cardinals.

Of course, the book is a work of fiction, but Grisham captured precisely the feeling of Arkansans about baseball.

Once during a radio broadcast in the 1980s, I remember Mike Shannon talking to someone in the booth who had never visited Arkansas.

"You've never been to Arkansas?" Shannon asked. "Oh, that's great Cardinal country."

And he's right. For at least four generations, anyone in Arkansas who cared about baseball kept up with the Cardinals.

And they still do. Even though we live in an age in which one can follow any major league team anywhere (through the modern miracles of the internet and ESPN), the Cardinals remain the main draw throughout the region.

In the heart of the United States, it's a part of our history, a part of our culture, and who we are.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Traditionally, if a person liked baseball and grew up in Arkansas, it was hard not to follow the Cardinals. This piece was originally published in newspapers on May 11, 2016

by David Wilson

St. Louis Cardinal baseball, over the course of its 124-year history, has developed a strong regional appeal that stretches in several states in the central part of the country, including Arkansas.

Part of the reason for that development is that in the earliest decades of major league baseball, St. Louis, as the westernmost team, was geographically situated to capture the attention of most of the Midwest.

It is understood that there is a growing interest in Northwest Arkansas with the Kansas City Royals, especially with their success in recent years, but the Cardinals simply have a longer relationship with Arkansans.

I grew up in Northeast Arkansas, where I learned of Cardinal baseball at a very young age by listening to Jack Buck, Harry Caray, (and later Mike Shannon) do the radio broadcasts of the games. I was probably three years old when I first remember hearing their voices give the count of balls and strikes on summer evenings.

My dad had the radio tuned to the Cardinal games because it was something he began as a boy living in rural Arkansas in the 1940s.

"We shelled beans and peas and listened to the ball game in the evening," my dad said. "We couldn't go to bed until all the beans and peas were shelled. We listened to Gabby Street and Harry Caray do the games. Gabby Street was the one they called 'The Old Sarge.'"

But my dad wasn't among the first in Arkansas to grow up listening to Cardinal broadcasts. In fact, it began as early as the 1920s when people started getting electricity and their first radio.

As far as Arkansas was concerned the Cardinals were not just the only game in town but the only game in the region.

Two different books by John Grisham (A Painted House and Calico Joe) provide insight in to how people in Arkansas followed the Cardinals and all of Major League Baseball during those decades.

A Painted House opens this way: "It was a Wednesday, early in September 1952. The Cardinals were five games behind the Dodgers with three weeks to go, and the season looked hopeless. The cotton, however, was waist-high to my father, over my head, and he and my grandfather could be heard before supper whispering words that were seldom heard. It could be a 'good crop.' ''

Calico Joe was about a young baseball player from the town of Calico Rock in north central Arkansas. He made a tremendous impact as a rookie with the Chicago Cubs and one of the subplots was how the people in Calico Rock and the surrounding area had trouble rooting for the Cubs when their hearts were always with the Cardinals.

Of course, the book is a work of fiction, but Grisham captured precisely the feeling of Arkansans about baseball.

Once during a radio broadcast in the 1980s, I remember Mike Shannon talking to someone in the booth who had never visited Arkansas.

"You've never been to Arkansas?" Shannon asked. "Oh, that's great Cardinal country."

And he's right. For at least four generations, anyone in Arkansas who cared about baseball kept up with the Cardinals.

And they still do. Even though we live in an age in which one can follow any major league team anywhere (through the modern miracles of the internet and ESPN), the Cardinals remain the main draw throughout the region.

In the heart of the United States, it's a part of our history, a part of our culture, and who we are.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on March 10, 2018 06:48

March 9, 2018

Learning from one of the best

WRITING

Note: In the spring of 1981 I first read the book On Writing Well by William Zinsser. Since that time, I got a new copy each time a new edition came out and read it again. It is the best I can recommend on communicating effectively in writing. I have written about Zinsser on several occasions, and the following piece was printed in the Jefferson City News Tribune on March 18, 2012:

by David Wilson

Last week in this space we discussed the importance of students having opportunities to learn to write well. By practicing writing, students develop a skill essential for success and can enhance their learning in any subject area.

William Zinsser is a lifelong journalist and nonfiction writer who has much to say along these lines.

His classic book On Writing Well has been through multiple editions and sold more than a million copies. It is a cherished favorite, not just for writers, but for educators, for students, for those in business, and for anyone who wants to clearly communicate.

Zinsser began his career in 1946 at the New York Herald Tribune. His resume includes free-lance work for several magazines, authoring 18 books, teaching at Yale University, and in more recent years, writing a weekly blog.

He writes with clarity about how writing should be a tool for conveying ideas.

His book Writing to Learn, published in 1988, has a number of insights worth examining.

Zinsser contends that if you can think clearly, you can write clearly, about any subject at all. That’s good news for students who shy away from writing projects, as well as for teachers who aren’t accustomed to teaching writing skills in their area of expertise.

Zinsser has a vast experience in the craft of writing, but has also helped colleges implement writing across the entire curriculum.

Teaching writing in all subject areas is important, he said, because writing itself is important to individual success.

“Far too many Americans are prevented from doing good useful work,” he wrote, “because they never learned to express themselves. Contrary to general belief, writing isn’t something that only ‘writers’ do; writing is a basic skill for getting through life.”

Many individuals, both students and adults, approach writing with some apprehension because they are not used to doing it, but Zinsser said writing is simply “thinking on paper.”

When students write and re-write, it forces them to think and re-think.

Zinsser wrote, “…in the national furor over ‘why Johnny can’t write,’ let’s not forget to ask why Johnny also can’t learn. The two are connected. Writing organizes and clarifies our thoughts.”

Zinsser makes some very good points, and they must be considered in the discussion about how American schools can improve.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Note: In the spring of 1981 I first read the book On Writing Well by William Zinsser. Since that time, I got a new copy each time a new edition came out and read it again. It is the best I can recommend on communicating effectively in writing. I have written about Zinsser on several occasions, and the following piece was printed in the Jefferson City News Tribune on March 18, 2012:

by David Wilson

Last week in this space we discussed the importance of students having opportunities to learn to write well. By practicing writing, students develop a skill essential for success and can enhance their learning in any subject area.

William Zinsser is a lifelong journalist and nonfiction writer who has much to say along these lines.

His classic book On Writing Well has been through multiple editions and sold more than a million copies. It is a cherished favorite, not just for writers, but for educators, for students, for those in business, and for anyone who wants to clearly communicate.

Zinsser began his career in 1946 at the New York Herald Tribune. His resume includes free-lance work for several magazines, authoring 18 books, teaching at Yale University, and in more recent years, writing a weekly blog.

He writes with clarity about how writing should be a tool for conveying ideas.

His book Writing to Learn, published in 1988, has a number of insights worth examining.

Zinsser contends that if you can think clearly, you can write clearly, about any subject at all. That’s good news for students who shy away from writing projects, as well as for teachers who aren’t accustomed to teaching writing skills in their area of expertise.

Zinsser has a vast experience in the craft of writing, but has also helped colleges implement writing across the entire curriculum.

Teaching writing in all subject areas is important, he said, because writing itself is important to individual success.

“Far too many Americans are prevented from doing good useful work,” he wrote, “because they never learned to express themselves. Contrary to general belief, writing isn’t something that only ‘writers’ do; writing is a basic skill for getting through life.”

Many individuals, both students and adults, approach writing with some apprehension because they are not used to doing it, but Zinsser said writing is simply “thinking on paper.”

When students write and re-write, it forces them to think and re-think.

Zinsser wrote, “…in the national furor over ‘why Johnny can’t write,’ let’s not forget to ask why Johnny also can’t learn. The two are connected. Writing organizes and clarifies our thoughts.”

Zinsser makes some very good points, and they must be considered in the discussion about how American schools can improve.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on March 09, 2018 18:20

March 6, 2018

You don't have to like baseball to enjoy spring training!

BASEBALL

Column published in newspapers on March 7, 2018

by David Wilson

My Dad loved watching St. Louis Cardinal baseball but my Mom didn’t like it much.

But somehow, they made the marriage work.

In recent decades Dad had a Cardinal game on television almost every night and every weekend.

Mom sat with him in the living room, and I could say that she suffered in silence, but actually, she wasn’t always silent about it.

I told Mom once that she and Dad should go to Florida during March and watch the Cardinals in spring training.

“Oh I can’t do that—” she said.

“Wait a minute Mom,” I said. “It won’t be like going in to St. Louis and fighting the crowds to see a game. You will be around a different group of people, including a bunch of retired folks. And the weather won’t be like sitting in the heat and humidity of St. Louis in July. It will be pleasant.”

Mom was listening.

“Just go with Dad for one game,” I continued. “Heck, you don’t even have to watch it. You could just sit by him at the game and enjoy the weather and read.”

“And then,” I said, “after the game you could go do whatever else you want to do in Florida.”

As I described the possibilities to Mom I couldn’t help but think of a book called Spring Training by William Zinsser.

Zinsser was a great writer, and he spent time with the Pittsburgh Pirates during spring training in Florida in 1988.

The Pirates were an up and coming team and Zinsser—being the great writer he was—showed us a unique look at their spring development.

Zinsser wasn’t a sports writer, but it didn’t matter. When he wrote about spring training he did it better than any sportswriter could.

The idea of going to spring training may not appeal to you, but if you read Spring Training it might.

My Mom didn’t protest when I suggested that they go to Florida, but unfortunately they never made it to spring training. Dad had a rough time the last couple of years he was alive. He couldn’t just travel any time he wanted.

I do not, however, feel bad that they didn’t see a Cardinal game in spring training.

They got to visit many places, including Hawaii, Las Vegas; Savannah, Georgia; New Orleans; San Antonio; New Mexico; Arizona; San Diego; and yes, even Florida when they were younger (but not during spring training).

They did a lot together, but watching the Cardinals in the Florida sunshine wasn’t one of them.

Spring training is going on now, and I would love to go some year myself.

I would also like to have an extended stay in Arizona.

I’ve always said if money were no object that I would spend January through April in Arizona every year.

If I can’t do that, I’ll at least try to do two weeks there some year soon.

Arkansas is a great state and a great place to live, but to be honest, Arkansas doesn’t have much for me this time of the year.

And I’ll also check out Florida’s spring training before I get to the point that I can’t, like my Dad was during his last couple of years.

I’m going to do it for Dad. And for Mom. And for me.

Whether you make a trip like that is entirely up to you. But I think you should.

Even if you are like my Mom and don’t like baseball. You can go to the game and soak up the sun and read a good book.

Maybe Zinsser’s Spring Training.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on March 06, 2018 20:15

March 1, 2018

Learning Every Day by David Wilson, EdD

Published on March 01, 2018 19:50

February 28, 2018

EDUCATION: Will schools provide what students need?

EDUCATION

An excerpt from the book Learning Every Day by David Wilson, available on Amazon.com.

Students tell us school is boring and doesn’t have a direct connection to real life. Businesses say many graduates aren’t prepared for the working world. Universities frequently tell us high school graduates cannot successfully begin college level work. And media outlets often report American students are not keeping up with their counterparts in many industrialized countries. Clearly, changes are in order.

The entire picture, however, isn’t bleak. In schools throughout the country, educators have begun to look at research, collect data, and make decisions about practices that will get the best results.

Many schools are becoming more flexible in every area and there is a great opportunity for improvement.

And improve they must.

Making the changes to support what today’s students need will require communities all across the country to support a school model very different from the schools of the last 100 years. The biggest question is, will they?

An excerpt from the book Learning Every Day by David Wilson, available on Amazon.com.

Students tell us school is boring and doesn’t have a direct connection to real life. Businesses say many graduates aren’t prepared for the working world. Universities frequently tell us high school graduates cannot successfully begin college level work. And media outlets often report American students are not keeping up with their counterparts in many industrialized countries. Clearly, changes are in order.

The entire picture, however, isn’t bleak. In schools throughout the country, educators have begun to look at research, collect data, and make decisions about practices that will get the best results.

Many schools are becoming more flexible in every area and there is a great opportunity for improvement.

And improve they must.

Making the changes to support what today’s students need will require communities all across the country to support a school model very different from the schools of the last 100 years. The biggest question is, will they?

Published on February 28, 2018 18:34

Will schools provide what students need?

EDUCATION

An excerpt from the book Learning Every Day by David Wilson, available on Amazon.com.

Students tell us school is boring and doesn’t have a direct connection to real life. Businesses say many graduates aren’t prepared for the working world. Universities frequently tell us high school graduates cannot successfully begin college level work. And media outlets often report American students are not keeping up with their counterparts in many industrialized countries. Clearly, changes are in order.

The entire picture, however, isn’t bleak. In schools throughout the country, educators have begun to look at research, collect data, and make decisions about practices that will get the best results.

Many schools are becoming more flexible in every area and there is a great opportunity for improvement.

And improve they must.

Making the changes to support what today’s students need will require communities all across the country to support a school model very different from the schools of the last 100 years. The biggest question is, will they?

An excerpt from the book Learning Every Day by David Wilson, available on Amazon.com.

Students tell us school is boring and doesn’t have a direct connection to real life. Businesses say many graduates aren’t prepared for the working world. Universities frequently tell us high school graduates cannot successfully begin college level work. And media outlets often report American students are not keeping up with their counterparts in many industrialized countries. Clearly, changes are in order.

The entire picture, however, isn’t bleak. In schools throughout the country, educators have begun to look at research, collect data, and make decisions about practices that will get the best results.

Many schools are becoming more flexible in every area and there is a great opportunity for improvement.

And improve they must.

Making the changes to support what today’s students need will require communities all across the country to support a school model very different from the schools of the last 100 years. The biggest question is, will they?

Published on February 28, 2018 18:34

75 years ago during World War II: A two-part report

HISTORY

The following article appeared in newspapers on Feb. 21, 2018:

by David Wilson

In the second scene in the 1970 academy award-winning movie Patton, one gets a gruesome view of the results of a severe American defeat.

The scene depicted Kasserine Pass in Tunisia, North Africa during World War II.

Amidst the smoldering ruins of tanks and other armored vehicles, local Arabs were looting the valuables from the bodies of dead American soldiers.

American officers arrived in jeeps to survey the damage. They fired several rounds of ammunition in to the air, causing the looters to flee before they could pilfer more items.

Actor Karl Malden, playing the part of the General Omar Bradley, sadly scanned the scene. After such a humiliating American defeat at the hands of the Germans, there were lessons to be learned and changes that needed to be made.

The Battle of Kasserine Pass took place Feb. 19-25, 1943.

That was 75 years ago.

By all accounts, Americans were simply not prepared for their first major confrontation with Germany in World War II.

American soldiers lacked fighting experience, and they needed better leadership. In addition, the Allied command structure was inefficient and was too cumbersome to make prompt battlefield adjustments.

In head-to-head combat, German tanks were far superior to the American M-3 Lee and M-3 Stuart tanks that were widely used in the early-going in North Africa. Even when the larger American Sherman tanks were put in to the fight, they were still not the equal of German armor.

To make matters worse, the German effort in the North African countries was coordinated by a brilliant battlefield technician in General Erwin Rommel.

General Bradley wrote of the loss at Kasserine in his memoirs entitled A Soldier’s Story.

Bradley had been sent by General Dwight D. Eisenhower to investigate the matter and to report back.

In interviews with officers and noncoms, Bradley was told that the Germans were a strong adversary, but that the real reason for the loss was that the Americans simply hadn’t seen combat. He also learned that many of the officers no longer had confidence in the leadership of General Lloyd Fredendall.

Furthermore, the command structure was ineffective, and almost every last soldier knew it.

Historian Carlo D’Este wrote that one soldier quipped, “Never were so few commanded by so many from so far away.”

While no one blamed the loss entirely upon leadership, Eisenhower relieved Fredendall and replaced him with a hard-charging general.

In the movie Patton, the actor portraying General Bradley said, “Up against Rommel what we need is the best tank man we’ve got, somebody tough enough to pull this outfit together.”

“Patton?” one officer asked.

“Possibly,” Bradley replied.

The officer grinned. “God help us.”

In 1943 General George S. Patton was already known as a capable but flamboyant leader.

By the time the war was over in 1945, people would understand all too well that Patton was a man with shortcomings. But more importantly, the entire world would know that Patton had a gift for unleashing an army’s fury upon the enemy, and that gift helped the Allies secure victory in Europe.

The American failure at Kasserine Pass made it possible for Patton to step in and demonstrate his leadership ability. He soon got an important American win at El Guettar in Tunisia in March and April of 1943.

After American forces had been mauled by the Germans at Kasserine, El Guettar gave them the opportunity to bounce back. It was there, under Patton, that they got their first victory over Germany.

Patton himself would tell you that he was destined for greatness, with or without the American defeat at Kasserine, and he would be right.

But 75 years ago, an embarrassing defeat forced Americans to regroup—and in the midst of the largest war in history—they began their long march to victory.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Part 2:Further reflections on the war in North AfricaThe following article was originally published in newspapers on Feb. 28, 2018

Author Patrick Lencioni, an expert in establishing healthy dynamics at work, wrote in his book The Advantage that businesses, organizations, and individuals must make adjustments in the face of setbacks.

“People in a healthy organization, beginning with the leaders,” he wrote, “learn from one another, identify critical issues, and recover quickly from mistakes.”

And as you may have read here last week, that is basically what happened with American military forces who were fighting on the other side of the Atlantic 75 years ago.

Americans suffered a terrible defeat at the hands of Germany at Kasserine Pass in North Africa, but the leadership—under General Dwight D. Eisenhower, General Omar Bradley, and General George S. Patton—quickly determined what was wrong and set out immediately to make changes.

We cannot always make the assumption that principles that work in a business in the 21st century worked equally as well 75 years ago and brought success on battlefields on the other side of the world.

It’s just not that simple.

But there are some parallels.

In the 1970 movie entitled Patton, actors George C. Scott (who played Patton) had a telling conversation with actor Karl Malden (who played General Bradley).

Patton: Tell me Brad, what happened at Kasserine?

Bradley: Apparently everything went wrong.

Patton: I understand we had trouble coordinating the air cover.

Bradley: The trouble was no air cover. There’s one other thing I put in my Kasserine report. Some of our boys were just plain scared.

Patton: That’s understandable. Even the best fox hounds are gun-shy the first time out.

Patton: You wanna know why this outfit got the hell kicked out of ‘em? A blind man could see it in a minute. They don’t look like soldiers, they don’t act like soldiers, why should they be expected to fight like soldiers?

Bradley: You’re absolutely right. The discipline is pretty poor.

Patton: Well, in about 15 minutes we’re gonna start turning these boys in to fanatics. They’ll lose their fear of the Germans. I only hope to God they never lose their fear of me.”

After that Patton went to work, and while he shouldn’t get all of the credit for turning things around, at the very least, he was a strong catalyst.

The Americans had been beaten soundly at Kasserine, but no matter what the reasons were for the defeat, there rested within most soldiers a fierce determination to come back strong.

Ernie Pyle was a Pulitzer prize winning journalist who wrote stories about the common soldier in World War II.

He was in North Africa and knew all about Kasserine, but he still believed in the American effort.

“You need feel no shame nor concern about their ability,” he wrote. “There is nothing wrong with the common American soldier. His fighting spirit is good. His morale is okay. The deeper he gets into a fight, the more of a fighting man he becomes.”

The modifications in the Allied effort brought great results.

The Americans—along with the British—would eventually run the German armies completely out of the continent of Africa.

After that, the Allies took Sicily, and then Italy, and then began gearing up for a massive invasion of the mainland of Europe.

During the early days of America’s involvement in World War II, Germany controlled almost all of Europe, but the American military had learned much from its opening defeat 75 years ago.

And while there were many battles still to be fought, Americans had gained valuable battlefield experience. Furthermore, America itself was pouring more men and materials in to the fight.

They wouldn’t stop fighting in Europe until Hitler was dead and all of Germany capitulated.

Erwin Rommel, possibly the best of Germany’s generals, wrote that the American response at Kasserine was crucial.

“In Tunisia,” he said, “the Americans had to pay a stiff price for their experience, but it brought rich dividends.”

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

The following article appeared in newspapers on Feb. 21, 2018:

by David Wilson

In the second scene in the 1970 academy award-winning movie Patton, one gets a gruesome view of the results of a severe American defeat.

The scene depicted Kasserine Pass in Tunisia, North Africa during World War II.

Amidst the smoldering ruins of tanks and other armored vehicles, local Arabs were looting the valuables from the bodies of dead American soldiers.

American officers arrived in jeeps to survey the damage. They fired several rounds of ammunition in to the air, causing the looters to flee before they could pilfer more items.

Actor Karl Malden, playing the part of the General Omar Bradley, sadly scanned the scene. After such a humiliating American defeat at the hands of the Germans, there were lessons to be learned and changes that needed to be made.

The Battle of Kasserine Pass took place Feb. 19-25, 1943.

That was 75 years ago.

By all accounts, Americans were simply not prepared for their first major confrontation with Germany in World War II.

American soldiers lacked fighting experience, and they needed better leadership. In addition, the Allied command structure was inefficient and was too cumbersome to make prompt battlefield adjustments.

In head-to-head combat, German tanks were far superior to the American M-3 Lee and M-3 Stuart tanks that were widely used in the early-going in North Africa. Even when the larger American Sherman tanks were put in to the fight, they were still not the equal of German armor.

To make matters worse, the German effort in the North African countries was coordinated by a brilliant battlefield technician in General Erwin Rommel.

General Bradley wrote of the loss at Kasserine in his memoirs entitled A Soldier’s Story.

Bradley had been sent by General Dwight D. Eisenhower to investigate the matter and to report back.

In interviews with officers and noncoms, Bradley was told that the Germans were a strong adversary, but that the real reason for the loss was that the Americans simply hadn’t seen combat. He also learned that many of the officers no longer had confidence in the leadership of General Lloyd Fredendall.

Furthermore, the command structure was ineffective, and almost every last soldier knew it.

Historian Carlo D’Este wrote that one soldier quipped, “Never were so few commanded by so many from so far away.”

While no one blamed the loss entirely upon leadership, Eisenhower relieved Fredendall and replaced him with a hard-charging general.

In the movie Patton, the actor portraying General Bradley said, “Up against Rommel what we need is the best tank man we’ve got, somebody tough enough to pull this outfit together.”

“Patton?” one officer asked.

“Possibly,” Bradley replied.

The officer grinned. “God help us.”

In 1943 General George S. Patton was already known as a capable but flamboyant leader.

By the time the war was over in 1945, people would understand all too well that Patton was a man with shortcomings. But more importantly, the entire world would know that Patton had a gift for unleashing an army’s fury upon the enemy, and that gift helped the Allies secure victory in Europe.

The American failure at Kasserine Pass made it possible for Patton to step in and demonstrate his leadership ability. He soon got an important American win at El Guettar in Tunisia in March and April of 1943.

After American forces had been mauled by the Germans at Kasserine, El Guettar gave them the opportunity to bounce back. It was there, under Patton, that they got their first victory over Germany.

Patton himself would tell you that he was destined for greatness, with or without the American defeat at Kasserine, and he would be right.

But 75 years ago, an embarrassing defeat forced Americans to regroup—and in the midst of the largest war in history—they began their long march to victory.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Part 2:Further reflections on the war in North AfricaThe following article was originally published in newspapers on Feb. 28, 2018

Author Patrick Lencioni, an expert in establishing healthy dynamics at work, wrote in his book The Advantage that businesses, organizations, and individuals must make adjustments in the face of setbacks.

“People in a healthy organization, beginning with the leaders,” he wrote, “learn from one another, identify critical issues, and recover quickly from mistakes.”

And as you may have read here last week, that is basically what happened with American military forces who were fighting on the other side of the Atlantic 75 years ago.

Americans suffered a terrible defeat at the hands of Germany at Kasserine Pass in North Africa, but the leadership—under General Dwight D. Eisenhower, General Omar Bradley, and General George S. Patton—quickly determined what was wrong and set out immediately to make changes.

We cannot always make the assumption that principles that work in a business in the 21st century worked equally as well 75 years ago and brought success on battlefields on the other side of the world.

It’s just not that simple.

But there are some parallels.

In the 1970 movie entitled Patton, actors George C. Scott (who played Patton) had a telling conversation with actor Karl Malden (who played General Bradley).

Patton: Tell me Brad, what happened at Kasserine?

Bradley: Apparently everything went wrong.

Patton: I understand we had trouble coordinating the air cover.

Bradley: The trouble was no air cover. There’s one other thing I put in my Kasserine report. Some of our boys were just plain scared.

Patton: That’s understandable. Even the best fox hounds are gun-shy the first time out.

Patton: You wanna know why this outfit got the hell kicked out of ‘em? A blind man could see it in a minute. They don’t look like soldiers, they don’t act like soldiers, why should they be expected to fight like soldiers?

Bradley: You’re absolutely right. The discipline is pretty poor.

Patton: Well, in about 15 minutes we’re gonna start turning these boys in to fanatics. They’ll lose their fear of the Germans. I only hope to God they never lose their fear of me.”

After that Patton went to work, and while he shouldn’t get all of the credit for turning things around, at the very least, he was a strong catalyst.

The Americans had been beaten soundly at Kasserine, but no matter what the reasons were for the defeat, there rested within most soldiers a fierce determination to come back strong.

Ernie Pyle was a Pulitzer prize winning journalist who wrote stories about the common soldier in World War II.

He was in North Africa and knew all about Kasserine, but he still believed in the American effort.

“You need feel no shame nor concern about their ability,” he wrote. “There is nothing wrong with the common American soldier. His fighting spirit is good. His morale is okay. The deeper he gets into a fight, the more of a fighting man he becomes.”

The modifications in the Allied effort brought great results.

The Americans—along with the British—would eventually run the German armies completely out of the continent of Africa.

After that, the Allies took Sicily, and then Italy, and then began gearing up for a massive invasion of the mainland of Europe.

During the early days of America’s involvement in World War II, Germany controlled almost all of Europe, but the American military had learned much from its opening defeat 75 years ago.

And while there were many battles still to be fought, Americans had gained valuable battlefield experience. Furthermore, America itself was pouring more men and materials in to the fight.

They wouldn’t stop fighting in Europe until Hitler was dead and all of Germany capitulated.

Erwin Rommel, possibly the best of Germany’s generals, wrote that the American response at Kasserine was crucial.

“In Tunisia,” he said, “the Americans had to pay a stiff price for their experience, but it brought rich dividends.”

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on February 28, 2018 18:23

February 25, 2018

Assessment motivates students

EDUCATION

Changing how we think in schools

A very relevant article originally published on Jan. 22, 2012

by David Wilson

Years ago when I was teaching junior high students, we took official grades on some student work but not on others.

If student work was not graded, it still had great value when it was used as student practice or as classroom review.

One day, some students said if the work didn’t have a grade attached to it, then they weren’t doing it.

It was an excellent moment for a good classroom conversation, and we had one at that time.

I said, “Wait a minute everyone. Why are we here anyway? Are we here to learn or are we here to collect numbers to put in the grade book?”

From that point on our conversation went well. The students generally agreed they were in school to learn, but for years in school their efforts had been paid for with points.

That was their experience, and they were conditioned to expect it would always work that way.

Today, that trend continues in most classrooms, because the idea of all work having a numerical grade attached to it is ingrained in education.

It is not, however, considered the best recommended practice.

A number of school districts have embraced the idea of creating quality assessments through strategies known as Assessment for Learning (AFL), as opposed to simply doing assessment of learning after a unit of instruction.

When explored this thoroughly when I was a part of the administrative team at Jefferson City High School in Jefferson City, Missouri.

Assessment for learning requires a shift in thinking among educators. It also requires training, collaboration, and experimentation in each class.

Rather than doing assessment to collect grades, assessment for learning is set up to use assessment to provide feedback to students, parents, and teachers, and to use that information to tailor learning to meet each student’s needs.

Assessment for learning also provides increased student motivation because students can assess their own efforts, allowing them to see what they’ve done right, where they can improve, and where they go from there.

Students are like any of us. They are motivated by being provided the right information, believing what they are doing is important, feeling successful, and being in control of what they are doing. Assessing for learning helps with all of that.

Research has demonstrated that utilizing ongoing assessment in class greatly motivates students and increases academic achievement.

We can be thankful that educators are dedicated to making such changes for the better. It is hard work but it can be done, and is well worth the effort.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Changing how we think in schools

A very relevant article originally published on Jan. 22, 2012

by David Wilson

Years ago when I was teaching junior high students, we took official grades on some student work but not on others.

If student work was not graded, it still had great value when it was used as student practice or as classroom review.

One day, some students said if the work didn’t have a grade attached to it, then they weren’t doing it.

It was an excellent moment for a good classroom conversation, and we had one at that time.

I said, “Wait a minute everyone. Why are we here anyway? Are we here to learn or are we here to collect numbers to put in the grade book?”

From that point on our conversation went well. The students generally agreed they were in school to learn, but for years in school their efforts had been paid for with points.

That was their experience, and they were conditioned to expect it would always work that way.

Today, that trend continues in most classrooms, because the idea of all work having a numerical grade attached to it is ingrained in education.

It is not, however, considered the best recommended practice.

A number of school districts have embraced the idea of creating quality assessments through strategies known as Assessment for Learning (AFL), as opposed to simply doing assessment of learning after a unit of instruction.

When explored this thoroughly when I was a part of the administrative team at Jefferson City High School in Jefferson City, Missouri.

Assessment for learning requires a shift in thinking among educators. It also requires training, collaboration, and experimentation in each class.

Rather than doing assessment to collect grades, assessment for learning is set up to use assessment to provide feedback to students, parents, and teachers, and to use that information to tailor learning to meet each student’s needs.

Assessment for learning also provides increased student motivation because students can assess their own efforts, allowing them to see what they’ve done right, where they can improve, and where they go from there.

Students are like any of us. They are motivated by being provided the right information, believing what they are doing is important, feeling successful, and being in control of what they are doing. Assessing for learning helps with all of that.

Research has demonstrated that utilizing ongoing assessment in class greatly motivates students and increases academic achievement.

We can be thankful that educators are dedicated to making such changes for the better. It is hard work but it can be done, and is well worth the effort.

David Wilson, EdD, is a communications director and former high school principal. His book Learning Every Day is available on Amazon.com. You may email him at ledauthor@gmail.com.

Published on February 25, 2018 16:26