R.M. Archer's Blog, page 6

July 30, 2024

Realm Makers Recap – 2024

After years of putting it on my list of annual goals… I finally made it to Realm Makers.

I’ll admit, it wasn’t exactly what I was expecting. It was very scheduled, which I should have expected, and this made it a lot more class-heavy and a lot less people-focused. But some of that is in what you do with it; when I go back, I’ll try to hold the schedule more loosely and prioritize conversation more highly.

I did get to meet so many people that I’ve known online for ages but had never seen face-to-face! There’s photographic evidence of most of those meetings.

I also got to meet Shannon Dittemore, Lindsay Franklin, and Nadine Brandes! (Sadly, I was quite tired that night and you can’t tell how excited I was to meet Nadine.)

Shannon was lovely to meet and learn from; I attended her class on developing characters and also got to sit with her for lunch on Thursday, so I got to learn a lot from her and you will be seeing posts inspired by things she said!

There were also people I missed and didn’t say hi to, Candace Kade and Jenna Terese chief among them, whom I’ll have to seek out next time.

The sessions were, overall, helpful and encouraging! There were some things I questioned or would have done differently, but I really appreciated the emphasis on going out as God’s co-creators, creating with Him and taking dominion under Him as He commanded. (I did notice the term “dominion” was never used, the “dominion mandate” was never referenced, but I wonder if that’s more common in certain circles and less commonly used overall than I realized?)

I came away with a somewhat mixed view of the Christian writing community. On the whole, it was great to see such a focus on bringing Christian creatives together, on combating the splintering of artistic Christian communities that I’ve seen happening, and on creating with God and for His glory. There were also some weak spots, some compromises, some places where I wondered (not for the first time) if there are any Christian publishers I would actually be fully comfortable partnering with. But I also heard from authors and agents who were really solid, authors I’m happy to call friends, authors I would collaborate with any day of the week and I’m really excited to see succeed. The Christian writing community just is a mix, I think, just as the Church is, and I hope that we see weak areas strengthened and strengths used to their full God-given potential for His glory.

I owe great thanks to Sarah Grimm for her mentorship. Brief though our session was, it helped a lot to remind me I don’t have to listen to every “should” and to get me thinking about other false ways I was thinking about my projects. (I’ll be talking about that more in an email on Friday, so sign up to the newsletter if you’re interested in hearing some of the thoughts I’m reworking and what it means for my primary writing projects!)

I also owe thanks to Janeen Ippolito for taking time to talk to me about worldbuilding, look over the one-page summary of my worldbuilding book, and give advice on how to strengthen the idea. (Also to Allen Arnold just for saying he liked my title. That was reassuring as it was an experimental title chosen because I knew my behind-the-scenes title was too vague!)

Also, multiple people surprised me with how much I had impacted them. One friend came up to a table where I was sitting with a bunch of authors I’d been super excited to meet because they’re awesome and I was somehow the one she seemed most excited to meet?? I was certainly not expecting that much excitement over little ol’ me, but she’s a delightful friend and it was so lovely to finally meet her and hang out with her throughout the conference.

Sarah Rodecker and I got a picture together with her book Escape from Mathebos because I was her editor and helped make it happen, which is still crazy to think about. I can’t believe I’ve helped facilitate multiple publications now and books I’ve edited are on bookshelves and available for people to read and enjoy. (Obviously not all the credit is mine! The authors I’ve worked with have had amazing stories and I’ve been so privileged just to get to help them refine those stories so that they’re all the more powerful for readers!)

A third friend shared with me how much my Preptober Prompts event helped her find her writing style and write some of her favorite work, which made me squeal because what?? That event was that instrumental to people??

A fourth friend immediately introduced me to someone at her table and talked up my worldbuilding stuff just because I was standing there.

Each instance was so amazing and humbling, and I’m so grateful to God for letting me see the impact He’s worked through me. Some of it still doesn’t feel like it’s sunk in as real.

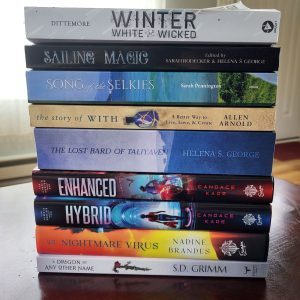

I bought books! I mean, how could you not, at Realm Makers. Winter White and Wicked came in before Realm Makers–I was about halfway through during the conference–and I came home to my copy of The Nightmare Virus, but everything else on the stack was purchased at Realm Makers. I limited myself almost entirely to books I’d already been planning to buy at some point anyway, with a couple exceptions.

I feel like I would be remiss not to mention my costume for the Awards Banquet. It was not one that anyone I ran into recognized, sadly but not unexpectedly. Any guesses?

Answer: Claudia Donovan from Warehouse 13. (If you haven’t watched the show yet, go do that. It’s amazing.)

Will I go to Realm Makers next year? I don’t know yet. It’s a couple hours closer, which is a point in its favor, and I do want to return to Realm Makers and I’d love to meet up with these author friends again sooner rather than later; but it extends over both Saturday and Sunday next year and I’m not sure if I’ll be ready to go again for a consecutive year, as it can be pretty overwhelming and attending once did leave me with mixed feelings about it as a whole. So we’ll see what the Lord orchestrates!

In the meantime, I’m settling back down to my writing and doing my best to keep in touch with the authors I met and preserve everything I learned so I don’t lose it–and so that some of it can benefit you, as well. If you’re interested in hearing more of those things I learned as I share them, I recommend subscribing to the newsletter! There are some things I’ll be sending there exclusively, and everything I post on the blog is shared there as well, so it’s the best place to go in order to not miss anything.

Comment below if you also attended and share some of your experience! If you haven’t attended before, would you in the future? Are there any other writing conferences you’ve attended and enjoyed? I’d love to hear from you!

The post Realm Makers Recap – 2024 appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

July 23, 2024

Book Review: World-Building from the Inside Out by Janeen Ippolito

There are a few reasons I don’t usually review craft books: 1) I don’t read that many, 2) I don’t feel equipped to review most of them, and 3) I’m more likely to lump them into a resource round-up and have a brief summary that contains most of my opinions on them and thus not feel like a full review is necessary. But this one is a worldbuilding book, so I feel equipped to comment on it, and I have enough thoughts to fill out a review (plus, I’m not doing another round-up any time soon).

This book has been on my TBR/wishlist for years, and what finally prompted me to pick it up was research into comparative titles for my own worldbuilding book. It’s really hard to find worldbuilding books that are really focused on the worldbuilding craft rather than being some sort of workbook, but this one is, so that was point 1 in its favor. Point 2 was reading the introduction and finding the premise focused around “cultural worldview” (which was actually in bold)! So I grabbed a copy for research. I will acknowledge upfront that the nature of my reasons for reading the book make it hard not to think about it in terms of comparisons between this book and mine, but I’ll do my best to be fair in my assessment.

What is World-Building from the Inside Out about?

Go to the heart of your world and build it well!

Memorable world-building enhances story, attracts readership, and sells books! Find the core of your science fiction or fantasy people and instill your narrative with universal themes and concepts derived from real-world cultures.

-Explore different religions and governments with concise entries that include ideas for plot and character development

-Develop key aspects of your society without getting caught up in unnecessary details

-Learn how the deeper effects of appearance and location can enhance your narrative

World-Building From the Inside Out challenges you to go deep and build fantastical worlds that truly bring your story to life!

The first thing that stood out to me about this bookwhen it arrived is how small it is; there are only about 60 pages of content to this book. The descriptions of it as a “primer” or “quick reference guide” are the most accurate. Janeen really does focus on the bare basics of each topic she covers in an effort to keep authors out of the weeds of “worldbuilder’s disease” as much as possible. If that’s what you’re looking for, this is the best I can recommend in terms of craft books.

Unfortunately, in some places it felt like this emphasis on simplicity cut out all nuance and turned things unrealistically black-and-white, which I believe can easily hurt the worldbuilding process and its support of themes and storytelling. There were also a number of places I felt the author’s bias on a topic came through very clearly, skewing the perception of certain worldbuilding options that could be used in more interesting ways. The appendix (chapter) on education felt especially narrow, and the government chapter had some inaccuracies in the way it defined certain systems along with a very American bias. Some bias is unavoidable, I know, but it made the options come across as very stereotyped. Again, if something very basic is what you’re looking for, this book might still be a helpful tool to start off with.

Another thing I noticed, as a side-effect of how brief Janeen kept the book, was that some of the organization was a little odd. When you only have a few chapters focusing on core topics, I guess you have to fit some smaller things in somewhere even if it’s not a perfect fit with the overarching topic. For example, the chapter on naming had a handful of points thrown in about language on a more general level, and “capitalism” started off the list of government structures despite being an economic system.

The strongest portions of this book, in my opinion, were the introduction, the chapters on art/media, the technology chapter, and the naming chapter. These felt the closest to the heart of the book’s premise and the most neutral in terms of how questions and options were presented (vs. the evident bias in some other chapters).

The book’s biggest weaknesses were, I think, largely side-effects of the focus on something simple and stripped-down for authors who need just the bare basics for a first draft. Some places felt like they’d been stripped down too far and key elements had been lost, the organization felt fudged in places, and a few points needed more research behind them. But if you’re an author who doesn’t want to get sucked down the worldbuilding rabbit hole and you’re looking for an introduction to the idea of building a culture around the idea of a cultural worldview, this is a decent primer.

The post Book Review: World-Building from the Inside Out by Janeen Ippolito appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

July 9, 2024

Book Review: Magnify by Stefanie Lozinski

It’s book review time again. Today we’re looking at Magnify, the first book in Stefanie Lozinski’s Storm & Spire series.

What is it about?

The dragons have fled the skies.

A noble House is clinging to life.

The God of gods is rising.

As the Envoy of the Four Kingdoms, Wes has had his purpose decided since birth: sacrifice the treasures of the people to the dragon gods, and they will keep Kaveryth safe.

For five years, he’s been forced to watch his Kingdom fall into ruin while carrying an unbearable grief of his own. The Elders insist that they must continue to be faithful to the Dracodei, but Wes is beginning to doubt that their protectors are holding up their end of the bargain.

Despite his misgivings, he continues to fulfill his duty—until he meets a misunderstood dragon who offers him a choice for the first time in his life.

Will he have the courage to make the sacrifice that truly matters?

Storm & Spire is a young adult Christian fantasy series, perfect for readers who enjoy fast-paced storytelling, fantastical lands, and devious dragons.

Review

Let’s get my biggest difficulty with this book out of the way first: the pacing. All of my struggles with this book came down to how quickly things moved along, from character development to choices made and events unfolding to learning about the world, everything felt like watching the world pass through a car window while you’re driving down the interstate. Nowhere did it feel like we got to settle in one place and really learn about what was happening, get a solid feel for the world, or process things with the character. Even when the characters were forced to sit and think, their thoughts didn’t seem to have a believable flow but a rush toward the conclusion the author wanted them to reach. This book wasn’t given breathing room, and I think every aspect suffered as a result.

That said, I think this could have been a great book had it been given that breathing room. The characters are foundationally solid and their arcs could have been really impactful given more time to develop, it seems like the politics and other worldbuilding elements were well thought through and just needed more time to be clearly explained through the story, and the themes of doubt and faith could have been really strong with the character arcs drawn out to better complement them. All of the pieces were definitely there, and I wouldn’t go so far as to say I didn’t enjoy this book, but I wish that everything had been given time to be fully explored and smoothed out into something that flowed better and was easier to follow.

One thing I did particularly appreciate was the subject of arranged marriage in this book; it has clear reasons behind it within the world (one thing that was well-explained in terms of worldbuilding), the match is clearly a good one–and the characters admit as much, and the main character’s reasons for struggling with the arrangement are more reasonable than “I don’t love you” or even “I’m in love with someone else.” Both parties take their responsibilities to their people seriously and are willing to prioritize the well-being of others over their own convenience, and I love to see that–especially in the commonly self-centered YA category.

Overall, this was not a bad book, it just needed more space to grow more naturally.

3 stars

Have you read this book? What did you think? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Want more book reviews and other bookish content delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up to the reading list below!

The post Book Review: Magnify by Stefanie Lozinski appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

July 2, 2024

5 Tips for Developing Character Quirks

One of my most popular blog posts is about five details that help bring characters to life. The first item on that list is character quirks, which I wasn’t very good at when I first wrote that post. While I’m still not a character quirk expert, I have learned a lot over my past couple of WIPs. Hopefully some of these tips and tricks I’ve learned will help you too!

First, let me define what I mean by “character quirks.” These are the little habits your character has in how they interact with the world around them and with other characters. Things they might not even be aware of, but that bring them to life and make them feel like real people by not only adding general flavor to their interactions but also communicating their deeper character traits through these smaller details. These are the little details you might pick up on to discover that a character is anxious or confident or was a musician or… whatever. As with character voice, these are the details that spring from deeper truths about your character, but these are the physical details vs. those that come through in the way they speak and describe things.

1. Start with the basicsSome of the easiest quirks to develop will be those that spring most directly from who a character is: their goals, motivation, confidence level, outlook on the world, etc. These are the easiest to draw from stereotypes or inherent habits based on one’s personality. For example, confident characters are more likely to casually take up space while more insecure characters might close in on themselves; characters who are very driven to focus on their goal and nothing else might always beeline through a crowd, while more easily distracted characters may find themselves talking to half the people along their route before they reach their destination; etc.

These core elements of your character can give you a starting point, but they may be only that. Knowing that your confident character is likely to take up more space than the shy one doesn’t tell you how the confident character takes up space or how the shy one hides in plain sight. The confident character might stand with her hands on her hips, have better posture, always put a leg up on a piece of furniture while she’s talking, sit in places she’s not supposed to, invade personal space, move around a lot, engage with every element of the setting around her, etc.; the shy one might slouch, curl up in a ball or keep her legs crossed when sitting, hide her hands in her sleeves, hide behind her hair, keep to the corners of the room, be very still through scenes, sit under blankets more, keep furniture between her and others in a room, etc. (And which quirks your character takes on will likely be influenced by other elements of their character, as well, including their appearance and choice of clothing, sense of propriety, general history and previous relationships, etc.)

By looking at specific examples of how people behave when they see themselves or others a particular way, and taking the rest of your character into account around that, you can start to piece together quirks for your character.

2. Look at their backgroundBackground can influence quirks based on other things, but it can also be a starting place in itself. For example, a character with a lot of experience in law enforcement will have very different quirks from a character who grew up in a cushy middle-class neighborhood. Someone with law enforcement training might always be watching for suspicious activity, while someone used to safety might only seek out the nearest clothing store.

A character’s background can influence their bearing and posture, willingness to try certain new things, what they do or don’t notice about people and/or their surroundings, etc. For example, the daughter of a seamstress or tailor might be very aware of the fashion choices of those around her and be able to glean a lot about someone based on how they dress; a thief may be very aware of security cameras or watchmen anywhere they go; a nobleman or politician may always be watching out for ways they can influence people in conversations and stay on their good side; etc.

Your character’s background can affect many aspects of their present character, and quirks are no exception. Have fun tapping into the goldmine of backstory when considering your character’s quirks!

3. Borrow from friendsReal people are full of quirks, and while you obviously don’t want to turn your characters into copies of people you know or be rude in your portrayal of their quirks, you can borrow traits from friends here and there–especially the positive traits.

A number of the character quirks present in Calligraphy Guild were borrowed from people I know. For example, bringing everything back around to God, giving off protective vibes without really trying, getting over an argument before you know it’s been resolved, etc. I mixed and matched, finding that certain characters were suited to quirks from multiple people, and multiple quirks from the same person were better suited to multiple different characters.

If borrowing quirks from friends seems awkward, you can also draw from yourself! This is a little trickier because it’s harder to be aware of your own quirks sometimes, but working to notice these things–or asking others to point out your quirks–can be another way to gather ideas for character quirks and make use of them as they suit your characters.

4. Practice observingFriends aren’t the only people you can observe for quirks–movies and TV shows are great to observe, too. By noticing how actors play their characters and what quirks they give them, you can get a great idea of how to endow your own characters with fitting mannerisms. For a somewhat extreme but thus easy-to-observe example, the main character of the show Perception is a paranoid schizophrenic professor; he carries a messenger bag with him everywhere, but instead of carrying it by its strap across his body he always clutches it to his chest. A viewer could easily assume that 1) he’s concerned about the bag or something out of it being snatched, so he wants it close, and 2) it may be comforting to clasp an object close and keep one’s arms close to the body (common insecure body language). It’s a quirk that reveals something about the character.

You can also practice simple people-watching in a café, library, etc. You don’t necessarily have to use the exact quirks you pick up, but observing a range of possibilities can help inspire further ideas when you create and write new characters. Perhaps you notice someone fiddling with the cord of their earbuds in the library and this inspires you to give your character a nervous habit of rolling the chain of the necklace she always wears between her fingers.

5. Use PinterestPinterest is such a useful tool for worldbuilding, character development, tone-setting, inspiration, etc., etc. I’ve picked out a lot of quirks for the characters of Lightning by looking at the Pinterest boards I built for them. Erika absolutely “makes eye contact with security cameras to assert dominance” (a quote pin from her board). I had several pins saved for Alaric that showed some sort of pressure against his palms (pressing a thumb against his palm, pressing his hands against a railing, etc.), so that became one of his anxious quirks. Because Pinterest is a visual medium, it’s especially good for figuring out quirks of body language, but text-based pins can also communicate quirks (like the security camera quote). If you’re struggling to develop your character’s quirks and you’ve created a Pinterest board for them, try studying the pins you’ve saved and looking for patterns!

There are my top five tips for developing character quirks. What have you found useful for developing character quirks? Which of these methods is your favorite?

Still feel like your character is lacking depth or uniqueness? Check out the Character Voice Questions worksheet to get at the heart of who your character is and how to communicate that heart!

The post 5 Tips for Developing Character Quirks appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

June 25, 2024

Book Review: Winter’s Maiden by Morgan L. Busse

Morgan Busse is an author who has come up numerous times over the years I’ve been in the online Christian writing world and a handful of her books have made it onto my TBR, but her upcoming Winter’s Maiden was the first of her books that inspired me to apply for an ARC. To my surprise, I got one, so today I’m here with my review!

(Required disclaimer that though I received a free copy to review, the following opinions are my own.)What is Winter’s Maiden about?

Warrior. Survivor. Daughter of the North.

From the moment she is born, Brighid fights to survive in the wastelands of Nordica as a clanless one. But when a new power arrives offering a trial to join the Nordic warriors, Brighid enters, hoping to rise above her station. Soon she becomes one of their fiercest fighters and joins the war against the south.

Kaeden carries the blood of the ancient Eldaran race in his veins but turns away from his heritage after the death of his parents. Years later, he is called back to his homeland and invited to be a healer for the southern forces. With the help of an old mentor, the power inside of him starts to awaken. However, his life is turned upside down when a mighty warrior of the Nordic forces is captured.

As Kaeden interacts with the enemy, he discovers there is a darkness behind the Nordic Wars, one that is manipulating the people of the north. But who will believe him? And is there a power strong enough to break the hold of this hidden adversary? Or will the world burn in the flames of war?

The first few chapters of this book really hooked me. We’re introduced to Brighid and the midwife Elphsaba who takes her in, and the midwifery scenes were excellent. Very vividly written, powerful, and great for establishing the characters and some of Brighid’s abilities. Once that was all established and the story moved on, however, the writing seemed much less consistently vivid and the depth of the characters’ perspectives was largely lost. There seemed to be a lot more telling than showing in the style of the writing, with a lot of areas feeling skimmed-over and a lot of developments attributed to characters without seeming to be earned on the page.

There were a number of scenes that did feel very cinematic, like I could vividly imagine how they might have played out in a movie very well, but that fell a little flat on the emotions in writing. They had not only the same level of imagery as a movie scene, but also the same level of distance (in a book that seemed to be intended to have a deep POV).

The characters were interesting in concept and clearly had interesting struggles, but they weren’t as compelling on paper as I would have liked because it felt like there was so little depth to the way they were written. That said, they were interesting enough for me to follow through an entire book while I was in an overall reading slump, so the writing certainly could have treated them worse.

I did wish we saw more of Gurmund; I found his POV chapters to be some of the most compelling, after the first few chapters with Brighid, and I would have loved to see more of his struggle with the other hjars and how he handled that; it felt like he sort of disappeared after the halfway point.

Kaeden, meanwhile, was a large part of the reason I picked up this book in the first place–I was interested in his role as a healer and seeing that play out, plus he’s mentioned in 2/3rds of the blurb–but as I neared the halfway point and he hadn’t shown up I actually started to wonder if I had confused this with another book. He doesn’t enter the story until just past the halfway point, and I didn’t feel that he got the same sort of establishment to his character that Brighid did; his “refusal of the call” felt very inconsequential on multiple occasions and I would have liked to see more of his struggle play out with more meaningful reluctance along his arc, as well as meeting him earlier in the book. The elements of the world that are introduced with him, however, I found to be some of the most interesting of the book!

Sadly, the worldbuilding–another reason I was interested in Winter’s Maiden–fell prey to the same lack of depth in the writing; the world itself was interesting, but didn’t feel well-explored in the way it was written. I did enjoy the spiritual parallels employed and how they were portrayed, and Brighid’s abilities were always interesting to see. I would have been interested to see more about the core conflict of the story established before it became a full war, because the motivations felt unclear to me. But overall the plot made sense, even if it had its weak spots.

Overall, this was a fine read. It only took me a few days to read despite my reading slump, so it has that going for it, and I do think that conceptually it’s a great book; I just wish that the writing had put more flesh on those concepts.

Rating: 3.5 stars

Want to get future reviews delivered straight to your inbox, along with edifying book recommendations and other bookish posts? Sign up below!

The post Book Review: Winter’s Maiden by Morgan L. Busse appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

June 18, 2024

Book Review: Silk by E.B. Roshan

Some of you may recognize E.B. Roshan’s name from when I reviewed her book Orchidelirium last year. Today I’m reviewing her upcoming MG graphic novel Silk, and I’d like to thank Ms. Roshan for allowing me to review another of her works!

(Required disclaimer that though I received a free copy to review, these opinions are my own.)What is Silk about?

Farz and his family are Silki-charmers; they follow the giant, spiderlike creatures known as “Silkis” through their jungle home, harvesting their precious silk. It’s been their family’s tradition for generations. But Silkis can be dangerous and not everyone wants them around. Farz may be ready to try a different life, but he doesn’t want the Silkis to disappear forever.

I’ll start off by saying I think Silk has a really interesting underlying story, working through how to handle changes in industry, especially when there’s a family tradition to uphold in the middle of it. This was part of what drew me in to reading it in the first place, and I do think it’s a strong story with a strong theme.

Most of my critiques of Silk come solely from its format. This is a graphic novel, but it felt like it was written in a way that would have been more fitting for a non-visual short story format. As a graphic novel, it felt very text-heavy rather than feeling like it utilized the visuals of its frames to full effect–especially as there were a handful of frames that seemed very repetitive, where we saw a character’s thoughts and later saw them communicating these thoughts to other characters with the same or very similar visuals as a backdrop. Graphic novels are a hard format to balance between text and visuals, so I think the skew is totally natural, but I would have liked to see the visuals leaned into more and used to greater effect.

That said, I do think that the visual design of the world was interesting–especially when it comes to the humanoid species that inhabit it. Their markings did seem a bit busy in black and white, but that’s a matter of preference and it was never so busy that it became unclear what was what within a frame. I’d definitely be curious to see more of these characters and their species in the future!

What immediately drew me to this story was the concept of the world and the family legacy idea tying into its silk industry, and I do think all of that was handled well. The world was visually interesting enough to warrant the format, the development of the silkis was interesting, the interactions between the characters were believable and compelling–especially between the main character Farz and his sister Diljin–and I think the theme was done well. While I would have liked to see a bit more visual depth and perhaps a bit more time spent developing the ideological clash between the siblings, I’m glad I read Silk and I look forward to more graphic novels from Ms. Roshan in the future!

Rating: 3 stars

Want to get future reviews delivered straight to your inbox, along with edifying book recommendations and other bookish posts? Sign up below!

The post Book Review: Silk by E.B. Roshan appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

June 11, 2024

Birth Rites & Celebration in Fantasy

As I promised in my last post about death (and funerary customs), this week I’m flipping things around and talking about new life! Birth rites and celebrations, to be specific (and not to be confused with birthday celebrations, which I covered a few weeks ago). So, without further ado, let’s look at how your culture might handle births and new babies!

Birth ItselfThis may be more or less relevant depending on what your story calls for, what characters are involved, and even whether your characters are human/oid or not, but it may be helpful to determine what the atmosphere of a birth is like in this culture.

First of all, think about who might be present for a birth. Is the father involved or kept out of the room? Are any relatives called? Is a midwife or doctor present? Is a religious official called right away?

Who is present will be somewhat dependent on where births usually take place. Are they expected to take place at a hospital or other place of medicine, or are they generally just at home? Depending on how nitty-gritty you want to get, you might consider whether there are any common pain-killers administered during birth or if women have all-natural births. (Some of these factors will depend on your culture’s view on medicine and the natural design of things.)

Birth might look very different if your culture doesn’t have live birth at all because their species lays eggs, for example, instead. In this case, birth may be considered to occur at the time of hatching and those beyond the mother and child may have very little to do with it. In cases like these, most of your attention may fall to the other considerations in this post due to nature as much as relevance.

NamingOne important thing to consider when a new character is born is how they receive their name (and when and from whom). Characters might receive their name at birth–whether their name is decided upon birth or has already been chosen beforehand–or may not receive their names until a dedication ceremony (which we’ll get to shortly) or even later. Some cultures may give names based on birth order or other in-born traits, in which case naming is probably quite simple and automatic upon birth.

If names are given by the parents, then they may be selected at or before birth and are likely used around the home immediately, but may or may not be announced to those outside the household until a dedication ceremony. If names are bestowed by a religious or political official, the family may use a nickname until the child’s legal name has been given with ceremony.

Some cultures may give children multiple names, whether with different meanings or for different uses. Some cultures may, for example, offer a name to be used in public and another name to be used around family and close friends. Some may have additional names that almost no one knows because names are thought to give power over the one named. For cultures where multiple names are common, different names may be given by different people and/or at different times.

You may also consider what names are generally expected to mean in this culture. Some cultures may choose names based on sound alone, others might select based on meanings that are important to families, others may refer to one’s place in society or one’s perceived destiny, others may indicate one’s familial ties and/or birth order, etc. Knowing these expectations can also allow you to break them as appropriate and write believable responses to this break in tradition.

Dedication RitesNot every culture will have something in this category, but you’ll likely want to at least ask if your culture has some sort of rite dedicating a new child to a religion or societal purpose, or simply announcing their birth to the community. Announcement ceremonies may fall more into the next category we’ll talk about, so for now we’ll focus on cultures in which new children are dedicated to a faith or to a specific purpose within their society.

Dedication to a religion might look like a baby dedication, an infant baptism, the offering of a child to work in a place of worship, or something else to similar effect. This would obviously involve the parents and the religious leaders–whether of their town or of the greater clergy of their religion–and may also include extended family and/or the greater faith community. There might be a sacrifice involved–to redeem a child or as a thank offering–a vow made by the parents and/or faith community, a blessing given to the child, a prophecy made, an immersion or anointing or some other symbol of what’s being given to the child or expected of them as they grow, etc.

Dedication to a certain societal role might look somewhat similar, though obviously civil leaders would be involved and religious leaders may or may not be. A new child might be assigned to a particular job; a particular type of job; a particular area of the town, region, etc.; in situations where children are distributed by the government rather than by birth perhaps they’re even assigned to a particular family after birth. In cultures where strength is important, a baby may be tested to gauge their current and future strength. As usual, the precise workings of such a ceremony will be shaped by what your culture values.

If your culture has either sort of dedication ceremony, consider what this means for your character in the long-term. What are the binding effects of such a ceremony? Are there guarantees of the blessings given? Is the child expected to grow up a certain way? What are the consequences if they try to veer from their destiny or assigned place in society? In short, can these rites be broken/rebelled against later in life and, if so, what are the consequences?

Celebration and HonorAs a last consideration directly related to the baby, think about how a new birth might be celebrated. Are there parties thrown to celebrate new births? If so, who is involved? What does the party entail? Are there gifts given, special foods eaten (perhaps related to fertility, healing, growth, etc.), decorations set aside for such an occasion?

Think about whether this is the same for every child or if these celebrations differ from one child to the next in a family. Perhaps the firstborn has greater honor, for example, or perhaps there are certain numbers that are sacred to this culture or a number of children a family is expected to bear in order to be considered “fruitful” or “accomplished” and celebrations are more distinct when these numbers are reached.

The style of celebration may also differ from family to family–based on differing values or means–or based on social class, religious background, etc.

Care for the FamilyLastly, think about how care for a new baby may extend to their family as a whole. Does this culture have anything akin to baby showers, to help the family accumulate the things they need for the new baby? Are meals brought to grant the mother a break following the birth? Are gifts given informally? Are older children welcomed into others’ homes or watched over by visiting friends and relatives to let the mother focus on the newest sibling? Are friends and relatives willing to tend to the house while the family focuses on their relationships with one another and adjusting to an additional member of the household?

The level of support that a family receives may depend on what this culture views as the community’s responsibility, what it views as the family’s responsibility, and how it views family as a whole. Joyful support may be much more common in a culture that values children, and may even increase as a family grows; while a culture that sees children as a burden or distraction may leave families to do more on their own and support may even taper off as a family has more children.

Births are an exciting thing, and new babies can add a lot more to a story–and characters’ lives–than seems to often be explored. Tell me in the comments: What are your favorite books that include new babies? Have there been births in any of your books?

Not sure how to develop a cohesive worldview for your culture that explores what’s important to you? Sign up to the newsletter and get access to a full worksheet of Worldview Focus Questions!

The post Birth Rites & Celebration in Fantasy appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

May 14, 2024

Creating Fictional Funerary Customs

Today’s topic might seem somewhat morbid, but it’s one that may be important if you plan to kill off any significant characters. (Don’t worry; I’ll be balancing it out by talking about the ceremonies surrounding new births next week!) If your character dies (or is thought to die), how is that handled in your world? How does your culture view death? That’s what we’ll be getting into today.

Cultural View of DeathThe first thing to determine is how your culture views death. Is death seen as an injustice, something against nature? Do they view it as being stolen away from the world or an eternal existence being cut short? Are characters viewed as being taken up by the gods when they die, for good or ill? Is death seen as honorable, whether as a whole or in certain contexts–such as through sacrifice for the character’s nation or religion? Is it seen as the natural mark of having fulfilled a life-long purpose? Does this culture have any concept of a resurrection or reincarnation after death?

Generally, this will boil down to two questions: Is death viewed as a negative, positive, or neutral occurrence? And what is believed to happen to those who die (in the immediate and in the long-term)? The answers to these two questions will influence pretty much everything else.

Another important question to ask in this context is what this culture believes about the body and soul, and how closely they’re believed to be connected–if at all. A culture that believes bodies have no purpose once the spirit leaves them will likely treat their dead very differently than a culture that believes a soul will one day return to its body or that the two are entirely inseparable (or one that doesn’t believe in souls at all).

Handling the BodyOnce you’ve developed your culture’s underlying beliefs about death, you can think about how they’re likely to handle the body of one who has died. Are they likely to burn the body as an offering to gods? Bury it intact to await a later resurrection? Give it to the sea to be reclaimed? Cremate the body so that it can be divided among beloved places or loved ones?

This is a question in which the relation of body and spirit will likely be a crucial point. If bodies and souls are never separated, a mariner culture might seek to return body and soul to the sea spirits they believe in while a culture that believes in keeping the deceased with their family might cremate them and divide the ashes; in a culture that believes souls return to their bodies, bodies may be buried, mummified, or otherwise kept whole and/or preserved (whether they’re preserved or merely kept whole may depend on whether they believe the body will be reused exactly as-is or if it will be remade and glorified); a culture that believes the body serves no purpose after death because it’s been abandoned by the spirit might burn the body or otherwise “dispose of” it, or might instead preserve it in a mummified state and/or coffin for the sake of remembrance.

You might also consider what would be thought of as dishonorable ways to handle a body. Maybe that mariner culture avoids land as much as possible, and being encased in it (buried) is a means of trapping a body forever and seen as a great punishment or dishonor. Or maybe cremation is considered desecration in a culture that believes souls will one day return to their bodies (this might even lead to a belief in ghosts as the spirits that have no bodies to return to, in certain cultures). This can also lead to some significant culture clash if two neighboring cultures–or an immigrant from some other culture and the culture they live in now–have vastly different ideas of how a body should be properly respected!

Memorialization might also look different from culture to culture. Some might mark graves–whether to honor those buried or for the practical purpose of avoiding trying to bury someone else in an occupied plot–others might keep artwork of the deceased in the homes of loved ones and otherwise not mark their identities, yet others might have entire elaborate tombs or coffins–perhaps filled with their most prized possessions either to preserve them or send them along with the deceased.

Handling the SpiritWe obviously touched on this somewhat in the previous section, but your culture’s customs may have additional elements that are specifically focused on properly seeing off the spirit of the deceased. Perhaps there is a custom designed to help send the spirit off to the afterlife–or merely symbolize that journey for those still alive; perhaps there is a memorial service allowing the deceased’s loved ones a chance to say goodbye; perhaps the deceased’s spirit must be set at peace in order to keep them from haunting their loved ones or their home, so any last tasks must be completed by the deceased’s loved ones soon after their death.

In Virilia, for example, those who die are thought to join the gods in the stars. Because of this, memorial services include a lantern-release ceremony that represents the deceased’s spirit rising to join the stars.

Care of the FamilyLastly, consider the effects of a character’s death on the family left behind. Is there a time of fellowship and encouragement after funerary ceremonies? Are meals and other general needs tended to by the community for a period after a relative’s death? How are families cared for after the death of a relative? Or are they expected to simply carry on with ordinary life after the deceased has been put to rest? What additional responsibilities fall on the family of the deceased after their death–whether the deceased’s everyday work or unfinished business? Do they have any support from the community in this additional work?

Think about how widows and orphans might be taken care of after a character dies. Are widows expected to remarry (whether it’s expected to be a relative of their deceased husband or simply a new husband from elsewhere in the community)? Are orphaned children taken in by other relatives, other members of the community, or an orphanage?

There you have the most critical considerations for funerary customs if you’re intending to kill off a character (or if you just want to be prepared for the possibility if the story calls for it). Have you ever killed off a character before? What is the strongest character death you’ve seen in a book, show, movie, etc.? (Warehouse 13, for me. If you know, you know.) Comment below!

Not sure what your culture’s values are yet or how to shape them effectively so they can inform these and other customs? Check out the worldview focus questions in the resource library!

The post Creating Fictional Funerary Customs appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

May 7, 2024

Worldbuilding on a Small Scale

Most of the time I write about how to build whole, sweeping settings and deeply nuanced cultures… but what if all you need for a story is a single town, a school, etc.? What do you prioritize when you’re worldbuilding on a small scale instead of an epic scale? That’s what we’re going to talk about today.

Core cultureFirst, as with larger cultures, you’ll need to determine the core of this town’s (or region’s, school’s, etc.) culture. What are the core values of this locale? Do they have any collective goals?

Are there any key sub-cultures to be aware of? (e.g. Hogwarts has an overall culture of learning and defense against evil, but each of the houses has their own unique sub-culture in addition.) What are each of their core values and goals?

And where are your primary characters supposed to fit into this culture and/or its sub-cultures?

DissonanceWith the core culture of the place determined, you can focus on what would clash with this culture. Where would conflict arise? This might be from some of these existing sub-groups (e.g. Slytherin causing problems at Hogwarts), a new group of outsiders with their own dissonant values (e.g. a town taken hostage by a group of bandits in a Western), or your main character themselves (e.g. the big city girl who returns to the small town in a Hallmark movie).

In any case, you want to stir up conflict. If your main character is the source of this dissonance, if they feel out-of-place in this culture, that can be an excellent source of internal conflict as well as external conflict (such as the city girl seeking individual success who is thrust back into a context of building up community, the academic pushed into a setting where they must put their knowledge to use in the real world, the character unfamiliar with social cliques who must find their place in a highly cliquish environment, etc.) But maybe your character is the hero preserving the culture’s main values from outsiders who want to destroy it, or they’re learning to balance the distinctions between sub-cultures as they sit on the fence between them (also good for internal conflict).

DetailsOnce you’ve established the foundational culture of the setting and at least one source of conflict, you can focus on the details to make your setting meaningful to the characters and vivid to readers.

Think about what your character would be doing in this setting. Do they have a job? Are they helping to plan an event or defend the setting? Is their goal to build relationships or learn something new? What do they do in their down time here? How does the setting shape their everyday life?

Consider the characters who would be around your main character. Who are their friends? Influences? Superiors? Do they have a love interest? How do these characters fit in with the culture you’ve established, and how do they challenge your character or reinforce the character’s existing ideas?

What are the most notable locations in this setting? Is there a gazebo in the center of town where the character likes to hang out? Is the school library a common location for strategy meetings or study sessions? Is town hall or the clan’s castle a recurring location? Where does your character live or sleep? Who do they associate with each key location?

And lastly, how does the setting feel? What is its overall aesthetic? Is it academic, astonishing, cozy, earthy, etc.? How can you shape the details of dress, food, architecture, etc.–as well as the behavior of the characters–to convey this feeling to the reader?

While you can build a small-scale setting with all the same depth as a grander-scale world (as almost a mini-version of a broader world), all you really need are the foundational values and the details that bring the setting to life.

Want to learn more about these foundational elements of worldbuilding, especially using details to convey depth without fleshing out everything underneath? Check out the Worldbuilding Toolbox!The post Worldbuilding on a Small Scale appeared first on Scribes & Archers.

April 30, 2024

Fantasy Cuisine & Mealtimes

Are you tired of feeding your characters generic medieval fare? Do you need to figure out who should be eating first or how food should be served up in your mealtime scenes? Are you just curious to see your world through the eyes of a foodie? Then this is the right post for you. I’ll be getting into what your characters eat, why they do or don’t eat the things that they do or don’t eat, and how meals look in your world. Let’s get started!

Food AvailabilityThe first and most obvious question to ask about food in your world is what your characters have access to. What edible plants and animals can be found in their geographical context? Beyond that, what edible plants and animals can be traded in from neighboring or even distant cultures? For that matter, what foods can be transported in your world once they’ve already been prepared? Do your cultures trade recipes at all?

Likewise, what foods are not available to this culture? Do they lack the equipment, ingredients, or recipes to make certain things? Are there plants that refuse to grow in their climate? Animals they don’t have the skill to husband? Knowing what they don’t have can be just as instrumental in shaping a fictional cuisine as knowing what they do have.

Food Prep OptionsOnce you know what ingredients your characters have at their disposal, you’ll also need to determine what sort of equipment they have on hand for storing, preserving, and preparing food. Do they have means of keeping things cool? If so, how cool? Does the same method work year-round or can they only keep things cold during certain times of year?

Do they cook things the traditional way–over heat–or are they prevented from using this method for some reason (because they live on boats, their climate is too cold for warmth to last long, they’re a species that can’t handle heat, etc.)? If they can’t use heat, do they have to age everything? Do they eat a lot of fermented foods? Do they freeze foods to eliminate germs instead? Do they even know/care about germs, or do they simply eat things raw?

Of course, some cultures may also use a mix of these methods–some foods may be heated, while others may be chilled, fermented, or eaten raw. In some cases, obviously, this will depend on the nature of the food in question; in others, it will be a matter of preference. More creative or experimental cultures may try the same foods with several different preparation methods to find out which ones are best–whether for flavor or health. Their priorities as a culture will dictate their priorities here (a scientific or health-focused culture will be more worried about eating well and eliminating threats to health, while cultures that value creativity or variety might simply be looking for as many ways to eat different things as possible)–as will their beliefs about food, specifically, which we’ll get into next.

Beliefs Around FoodOnce you know the breadth of the options available to your culture in a technical sense–the ingredients and equipment/skills they have at their disposal–you can look into how these options are shaped by your culture’s view of food on a spiritual and philosophical level.

The most broad consideration in this vein will be to think through what your culture sees as the purpose of food (or what 2-3 purposes they see food as serving, primarily). Do they see it only as a means to an end, fuel for their lives? Does it have spiritual meaning, a physical reflection of the way that people need to be spiritually nourished? Is it an art form? A tool for fellowship and hospitality? Is it an element of worship? Is food seen as a pleasurable thing to indulge in? The answer to this question will affect the breadth of what is eaten and how.

Next, consider whether there are any restrictions on what is seen as edible in this culture–beyond what is literally edible vs. inedible. Are certain plants or animals seen as “unclean”? Is the culture vegetarian? Pescatarian? Vegan? Are these guidelines seen as coming directly from a deity, or are they inferred from other values the deity has given them? (E.g. a culture that is anti-violence might see hunting as violent and thus be largely vegetarian, even if their deity hasn’t given them a directive not to eat meat.)

Lastly, are there any foods seen as sacred or otherwise special in this culture, set aside for particular purposes, contexts, or days? Are there foods set aside for birthdays, weddings, festivals, or religious ceremonies? Do particular combinations of foods mean something specific? Does this culture have ways of communicating through their food or the way their meals are laid out? Which leads us to…

Mealtimes & Mealtime EtiquetteHere we get beyond what your characters eat and into the details of when and how they eat. The most obvious thing to start with is to determine how often your characters have meals. They might be like hobbits, eating seven meals a day; they might have the American count of three; they might have one smaller meal and one larger meal; or they might only have one large meal per day. How often your characters eat will depend on a few things: how much they need to eat (particularly an important consideration for non-humans), their cultural view of the function of food (as previously discussed), and the depth of their understanding of nutrition (how their bodies respond to food when it’s spaced out vs. all at once, how they handle fasting, etc.). Cultures that see food as a mere necessity might have just one or two meals so they can get eating out of the way, or they might not have any set times because they just eat when they need to. Cultures that see it as a communal activity (and value community) might have more frequent meals as a means of drawing together families and communities–and granting more frequent opportunities for hospitality. Cultures that view it as an art form might have only one or two meals a day because it takes a while to prepare food to perfection. Other cultures may operate on a model of intermittent fasting, they might have one smaller meal in the morning to prepare characters for the day and a larger one in the evening to celebrate a good day’s work with family and friends, etc.

This ties in with the next question, which is: How are different meals set apart, if at all? Are there meals that are seen to serve a merely utilitarian function, while others are viewed as religious or communal? Are all meals family meals, or are some meals “every man for himself” and others designated to be spent with family? Are people in this culture expected to be ready to welcome strangers in for any meal (in a culture that values community and charity, for example), or can they be more relaxed and prepared only for their own families or expected guests?

What does it look like for your characters to prepare for a meal? What dishes and utensils are used, and how are they laid out before a meal? Does shifting their placement have meaning? (For example, in cultures where you can communicate that you’re finished or that you would like more of a certain dish by arranging your dishes and utensils a particular way.) Are there any ways to snub guests (or hosts) in the placement of dishes, which should generally be avoided? Is it expected that hosts and/or guests will wash their hands before a meal (or their faces or their feet, for that matter)? Are certain activities prohibited during a meal (such as singing, burping, placing elbows on the table, etc.)? On the flip side, is anything expected of those at a table together (such as passing dishes, exchanging stories, keeping silence, saying a prayer, etc.)? Is etiquette the same for adults and for children, or are there two different sets of expectations depending on a character’s age?

How are meals served? Does this culture generally use a buffet style, family style (passing dishes around), or plated ahead of time model? Are there guidelines for the order in which people are served at the table (does the oldest or youngest person go first, or are guests given preference, etc.)? Who generally does the serving (servants, the lady of the house, the head of the house, the children of the host, everyone serves themselves, etc.)?

Beyond the order in which food is served, what is the order of who may eat first? Are both orders the same? Can one’s place be forfeited (say, if a child reaches for the food before it’s been properly blessed and served are they moved to the end of the line) or can one be brought up in the line (say, if the host wishes to give special honor to a particular guest)?

Communal MealsNext, I want to bring up meals that are specifically communal and how etiquette does or doesn’t differ in these contexts. Some meals may be central to a community–think of things like block parties or celebrations that a whole community participates in around a meal. How do the rules of a meal change or stay the same? Are there changes made to simplify logistics? Or are logistics adjusted to accommodate the same types of etiquette?

Say you’ve decided that the head of a household says the blessing over a meal and gets to be served their food first. For community meals, does this privilege move upward to the head of the community, followed by the heads of household, then trickling down as usual? Or are tables set up for each household? Or does each table seat a few households, and the eldest head of household eats first at his table, followed by the others in age order? There are lots of variations you can explore from just one set of etiquette.

Meals to commemorate special events and holidays might also have different rules from the usual. Etiquette may be more formal (or more relaxed), or it might be changing for particular characters (if, for example, the celebration is for a coming-of-age ceremony or a new year and characters are moving out of childhood etiquette into adult etiquette). Certain foods may be enjoyed that aren’t on other occasions, special dishes may be brought out, special attire might be expected at the table, etc.

Religious meals have a whole new set of considerations, because these are likely symbolic and might even be perceived as sharing a meal with a deity. These meals might be taken more rarely and will likely have distinct requirements from other meals in terms of how they’re administered, by whom, and to what purpose. Distinct etiquette will likely flow out of this–though in some cases the etiquette may be largely parallel if the culture views all other meals as reflective of these sacred meals. Religious meals may hold symbolic meaning–reminders of particular religious events, for example–or may be seen as communion with a deity following a sacrifice, or mere fellowship with fellow believers and/or the deity/deities themselves.

Fasting and FamineLastly, I want to talk about the absence of food, starting with intentional absence of food (fasting) before getting into inadvertent absence of food (famine).

The first question is whether this culture sees fasting as a thing to do. Is it something they do for health reasons, religious reasons, or to share experiences with those battling famine? Or do they see it as ridiculous because food is a necessity that you shouldn’t withhold from yourself? If they do fast for one reason or another, how frequently do they do so? Is fasting something that’s done together as a community (either on a routine basis or as part of a particular, infrequent observance like Lent), or is it a private matter? Are both considered appropriate in different contexts?

How does this culture handle supplying food to those who have none? Do they have any equivalent to a soup kitchen–whether organized by a civil or religious body? Are members of the community expected to extend hospitality and feed those in need “on their own time”? Are scraps and fragments left at harvest time so that those who have need may gather? Are fields open to those who need to harvest food for themselves in general? Does this culture even care, or if this not an issue that they have addressed? (In some cultures at certain times, it might not be something they need to consider at all.)

What are the causes of famine in this culture’s part of the world? Do pests come through and destroy crops or infect livestock? Are natural disasters prone to destroy food supplies? Does this culture not tend to its soil well and thus have poor yield? Are they unskilled at raising their livestock, so they lose a lot of what meat or animal byproducts they would be able to use?

When famine does hit, are there any hardier sources of food that remain? What is left behind that they have to get creative with so they don’t get sick of it during droughts, blights, and other times of famine? (These might be crops or animals, depending on the needs of what they grow and raise.)

Lastly, where does this culture turn during a famine? What neighbors can be turned to when they have no food left? Who has better crops, more reliable weather, or stronger livestock and is willing to provide this culture with what they need? What is this extra food worth to this neighboring culture; what trades are agreed upon in these seasons?

This post was particularly question-heavy, but I’d love to hear in the comments which of these considerations most piqued your interest and what you’re most excited to work on next!

Want guidance on fleshing out the core elements of your culture, including its natural resources and core values? Sign up below to get the printable worldbuilding checklist, as well as a FREE 2-week mini-course to walk you through each item in more depth!

The post Fantasy Cuisine & Mealtimes appeared first on Scribes & Archers.