Stephen Roney's Blog, page 248

March 25, 2020

A Journal of the Plague Year

A beautiful spring day. A day of superlatives. India is in the largest lockdown/quarantine in history. Wall Street had its biggest one-day surge since 1933. The US just passed the largest spending bill in human history.

Oxford University has released a study arguing that, for all we know, the fatality rate for coronavirus is low. They theorize that fifty percent of Britons may already have been exposed. If so, the proportion of deaths is quite small.

I think this is delusional thinking. If fifty percent of the UK population has already been infected with only 433 deaths, how do you explain that Italy, with about the same population, has 7,000 deaths. That would mean almost 1000% of Italy must have been infected. Excuse my Italian, but is my math that bad?

I don’t know what they’re doing about testing in the UK, but Canada and the US are in effect doing random sampling now, and they are finding when they do test random samples, only a small percentage test positive for the virus.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 25, 2020 13:01

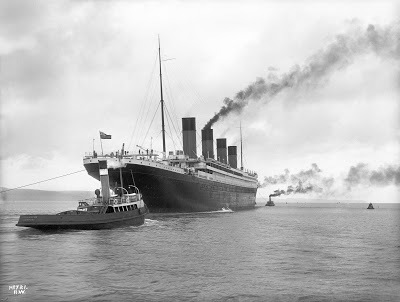

Cruising with Coronavirus on the Ship of Fools

One wants to believe that the clear and present crisis would bring us all together, forgetting our differences as we face, as humanity, a common enemy. As we all sing to one another from our balconies.

One wants to believe. Sadly, that is not the real world. It would be pleasant indeed if all our differences were due to simple misunderstandings, and all along we just needed more good will on both sides. But if it were so, we would be pretty dumb not to have done that long ago, without the crisis. People do not rape and murder over some silly misunderstanding.

The crisis is instead making our differences sharper, clarifying the distinction between sheep and goats. The good people are showing how good they are, doing what is necessary, even taking great personal risks, to help others more vulnerable. But the bad people are showing how bad they are, exploiting the crisis.

Unfortunately, some of those bad people are at high levels in government. The Democrats in the US Congress have taken the need for emergency legislation as an opportunity to force through 1,400 pages of measures largely unrelated to the crisis. Measures that could never pass a vote in the Senate as currently constituted, and cannot possibly be debated or even seen in time for a vote. In effect, they have put a gun to the heads of all Americans, to subvert democracy and seize power.

In Canada, the problem is with the sitting government. They took the parallel emergency bill as an opportunity to rush through the power for themselves to spend, tax, and borrow for the next 21 months without reference to parliament. This is, in effect, the suspension of the Canadian system of government and the seizure of dictatorial powers, by a minority government. It is only too reminiscent of Hitler’s legislation after the Reichstag fire.

In both countries, it looks as though the malefactors are now backing down. But aside from the mendacity of the original proposals, it seems they are delusional. They do not seem to grasp that we are all in this together; they do not seem to grasp that what they are doing will discredit them if they ever have to go before the people again.

A basic law of the universe: people who are confirmed malefactors tend to be delusional as well. You almost have to be, because to consistently choose the wrong, you need to somehow trick your own conscience.

The left have been mad as hatters for some time. A story widely circulated only a day or so ago blamed Trump because a couple drank aquarium cleaner in hopes of immunizing themselves against the virus. Someone in my Facebook feed claims that Trump has murdered everyone in the US who has died of coronavirus. Young people are licking toilet seats, and putting the video online. Reports come from Britain of people slashing ambulance tires, or running up and coughing in the faces of old people. A boomer friend asserts that, having grown up in the fifties, he is immune—the many childhood diseases he suffered through have given him all the antibodies he will need.

A lot of people are in denial here.

Perhaps Joe Biden is the reigning example: a symbol of it all. He’s been deliberately propped up on all sides to take the Democratic nomination, despite the growing public evidence that he is becoming senile. Faced with this alarming fact, the Democratic establishment continues to do nothing.

Even though doing nothing now dooms them in November, or the entire nation in January.

If a truth is unpleasant, they will just deny it. And they will even respond aggressively to anyone who asserts it.

The coronavirus, I still keep hearing, is no worse than the flu.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 25, 2020 08:00

March 24, 2020

A Journal of the Plague Year

Took my exercise stroll up to the corner to check whether the supermarket had instituted special shopping hours for the elderly and disabled. They had: 8-9 am, Tuesday and Friday. That should be a convenience, since there was a longer lineup to get in this time, even early in the morning. Perhaps half a block, with the shopping carts.

A bus went by with no passengers.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 24, 2020 08:31

A Journal of the Plague Year

Yesterday, back-to-back announcements from Boris Johnson in the UK, Doug Ford in Ontario, and Donald Trump in the US. Johnson was belatedly, but firmly, shutting everything down. No gatherings of more than two people. Ford was shutting all non-essential businesses.

And Trump was talking about getting people back to work.

Without his medical officer Fauci present, he was speaking more expansively of the hoped-for chloraquine treatment. He called it possibly “a gift from God.”

My notes say “evidence of the hand of God.” I’m not sure if those are Trump’s words, or my own.

Because I see evidence still of the hand of God. I previously thought it might be meaningful that the virus hit in China, where it is apt to destabilize an anti-religious government; and in a millenarian cult in South Korea, probably killing it. And in Iran, with an unstable Pharisaic regime that has been causing trouble in the region. Yet it was mysteriously sparing other countries. In hitting Europe hard, it seems to be targeting the “open-borders” concept of the EU.

Now it is in the US. In the US, where is the outbreak concentrated so far? In New York City, and along the West Coast. This is the heartland of the Democratic Party. Of more relevance, although the two overlap, this is the heartland of the postmoderns, the intersectionals, the woke.

At the same time, the various reactions to the virus seem to separate the sheep from the goats.

I think there is still room to suspect this is the hand of God.

If the chloraquine treatment does prove effective, and rolls out soon, this feels like the best divine end game. Like deus ex machina, a sunbeam breaking through the clouds.

In his speech, Trump seemed to give an explanation for the mystery I have mentioned here several times: why the virus seems to have largely spared several nations close to China. The Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, all should have been harder hit, but, until recently, seemed largely exempt. It looked to me and others as though it were related to climate. And Trump apparently thinks so too; but in an indirect way.

It is, he suggests, because they are malarial regions.

As a result, their hospitals and pharmacies stock a supply of chloraquine. It is used to treat malaria. Italy or Iran did not. Hearing of early success with the drug—as I did myself, on the internet, from Thailand—doctors were perhaps prescribing it for the cases they encountered. The cases tended to clear up quickly, and this reduced the time during which folks were infectious. So, less spread.

If things are starting to get out of hand now even in these countries, that kills the climate hypothesis, but does fit the chloraquine one. They have probably now depleted the local supply of the drug, and are unable to get more in, giving growing international demand.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 24, 2020 06:18

March 23, 2020

A Journal of the Plague Year

A friend with an Iranian wife confirms that Iranians are touchy-feely on greeting, like Italians. They kiss three times on the cheek, and embrace.

This seems to reinforce my thesis that the greater severity of the virus in Iran and Italy has to do with the dose you get at first exposure. A good argument for social distancing. You might get it from surfaces or air transmission still, but it is likely to be a mild case.

And reassuring in terms of the risks in Canada. Canadians are reserved.

Premier Ford was just on the television mandating the closure of all non-essential businesses, and extending the school closures. His health minister reassured everyone that they had ample medical supplies. Does that mean for what’s happening now, or what will be happening in two weeks?

Liquor stores remain open. Some are kvetching, but I think it is the right call. Some people are going to need that, at this of all times.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 23, 2020 11:47

Pluralism and Indifferentism

Mary is commonly shown with a serpent at her foot. Here Guan Yin baptizes a dragon at hers.

Mary is commonly shown with a serpent at her foot. Here Guan Yin baptizes a dragon at hers.William Lane Craig, of whom I am a huge fan, says that the biggest challenge for Christian apologetics today is “pluralism.” By this he means what Catholics call “indifferentism”: that all religions are equally true.

Craig rejects the claim that all religions are equally valid, reasonably enough, because they directly contradict each other. Islam, for example, condemns the Christian idea of the Trinity as idolatry, shirk: God is one. Buddhism denies the existence of a soul. Hinduism worships many gods. They cannot, therefore, all be true.

Objection, as Thomas Aquinas would say: I argue that if God exists, he is not going to allow us to be led astray. He is the good shepherd. He is not going to reveal truth only to the Europeans, or only to the Jews, and abandon everyone else. He is not going to penalize you for being born in Africa instead of Israel. The fundamental truth must be available to all.

Therefore, all major religions must at least be fundamentally true.

There is evidence that God has done this, too. How else explain the uncanny similarities among religions, on matters not subject to rational deduction. Why does every culture have a story of the Great Flood? Why does every culture have dragons, although they do not exist in nature? Why the uncanny similiarity in iconography between Mary in the West and Guan Yin in the East? How were the Romans or the Greeks able to identify their own gods worshipped far afield, wherever they conquered?

If they disagree on some point, as of course they do, there are several possibilities. One may be wrong, and the other right; but this point is not essential to salvation. Personally, I would put the Muslim or Protestant prohibition on images in this category: it is wrong, but as images are only a means to an end, not using them is not critical. I would hold the Buddhist or Hindu practice of vegetarianism morally superior to Christian or Muslim dietary rules; but not enough so to lose anyone’s salvation.

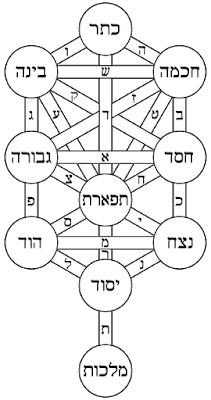

Or one may misunderstand what the other is really saying. Recently, Catholic and Lutheran authorities seem to have come to this conclusion regarding their different terminology over the Eucharist. I think this accounts as well for the Muslim disagreement with the Christian Trinity. The Muslims think this means three gods; yet Christians would find that interpretation appalling. Muslims speak of ninety-nine names of God; Jews speak of ten emanations of God. Some are personified. Is that so different? Are they, too, polytheists?

The ten emanations of God.

The ten emanations of God.So too with Christian criticism of Hinduism as polytheistic. Only a terminological difference, I believe. Hinduism believes in one “Godhead,” Brahman, which appears in many manifestations, “gods.”

Or they may be responding to different issues. For example, the obvious differences between Buddhism and the other major world religions can be accounted for by understanding Buddhism’s prime concern as psychological, rhetorical, rather than philosophical. Christian or Buddhist morality seems more personal, Jewish or Muslim more social, in its concerns.

When there is an apparent conflict among the major faiths, it is useful, and perhaps our duty, to look more carefully, and decide why. But even this cannot be of critical importance; God would not make salvation available only to the smarter among us. Sincere adherence to any major faith—I’m inclined to say any faith, so long as it is sincere―ought to be sufficient.

Craig points out a second common argument for asserting that all religions are equal: that God by his nature is beyond human understanding. Therefore, it is absurd to suggest that any religion has the real scoop: “God is not Christian.” Christianity cannot contain him. In effect, the argument is that all religions are false.

This is the argument by which I conclude that Christianity is superior. God IS Christian.

The argument is perfectly sound, so far as it goes, and is asserted by Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism almost as presented here: God is beyond human understanding.

But the fact that we cannot comprehend God is not decisive. It is not up to us. A loving and all-powerful God would want to reveal himself to us. Whether the image he offers us is comprehensive is not relevant: it is his chosen image, and he, being God, knows best. But, being God, we must also assume that he is capable of making it comprehensive, too.

Not wanting to abandon us, wanting us to know him, this is what he must have done. Sometime, somewhere.

Christianity asserts that he has expressed himself to us as Jesus Christ.

Buddhism, Judaism, or Islam offer no rival claimants. Hinduism does, with its concept of the avatar: Krishna, Rama, and others.

But Krishna or Rama seem literary characters, existing only in the mind’s eye, unrelated to any period in history or known historical persons or events.

Jesus, on the other hand, has clear historical warrant for his physical existence. As Craig has argued, there is even good historical warrant for his resurrection. This makes him, at least, a more comprehensive and definitive manifestation of the divine.

Therefore, while all religions are true, there seems solid reasons to believe Christianity is the gold standard.

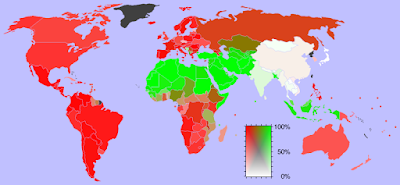

World distribution of the two largest faiths, Christianity (red) and Islam (green).Now go back to our premise, that God would not withhold the truth from anyone. It follows that he should also historically favour the spread of the faith that offered the most efficient path to salvation. Other faiths may endure because they are more efficient for those raised to a specific culture or set of circumstances. Islam, for example, might be better tailored to Arab sensibilities. Its allowance of polygamy makes practical sense in a desert environment. Conversely, it is virtually impossible to follow the fasting rules for Iftar above the Arctic Circle.

World distribution of the two largest faiths, Christianity (red) and Islam (green).Now go back to our premise, that God would not withhold the truth from anyone. It follows that he should also historically favour the spread of the faith that offered the most efficient path to salvation. Other faiths may endure because they are more efficient for those raised to a specific culture or set of circumstances. Islam, for example, might be better tailored to Arab sensibilities. Its allowance of polygamy makes practical sense in a desert environment. Conversely, it is virtually impossible to follow the fasting rules for Iftar above the Arctic Circle.Accordingly, the simple fact that Christianity is the largest and most widely distributed of world faiths seems further evidence that it is right—and not merely by the ad populum illusion. On this one issue, God has reason to be pulling the levers behind the scenes.

I am not at all keen on missionary activity directed at followers of some other major faith. Doing so seems a waste of effort. Adherents of other faiths must be fine so long as they are sincerely following it. Jesus himself says so: if a Jew cannot be a good Jew, he cannot be a good Christian. The proper mission field is among those who have fallen away, or who are despondent, or have no faith.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 23, 2020 06:42

March 22, 2020

A Journal of the Plague Year

Out on my daily rambles, I do not really see much—since I am practicing social distancing, and so no going in any shops that might still be open. I do see that others are not practicing social distancing—not keeping the suggested two metres apart. I see them standing around in small groups, and often blocking exits and entrances so that others cannot possibly keep their distance.

I note with concern that the local laundromat has closed due to the virus. How are people going to do their laundry? Should be okay for me; there are machines in my building. And, at worst, I have enough clothes to go without a laundry for several weeks. Especially if I am not going out.

There are still, it seems to me, some mysteries surrounding the coronavirus.

Why did it seem to spare the tropics for a time? It is now apparently spreading in the tropics as well, but at least it seemed to stall for a time.

And why does the death toll seem so much higher in Italy or Iran than in Taiwan or Korea?

Why are some young people with no underlying comorbidities dying? While others barely have any symptoms?

It might be that how bad a dose you get depends on how heavy the initial exposure is. Italians, after all, are a lot more touchy-feely than Koreans or Chinese. You meet a friend, you hug.

I don’t know about Iranians.

If this is right, it seems a second good reason for the “social distancing” regime. It may not only reduce the number of cases, but reduce the severity.

If you’re going to get it, good idea to try to make it a light dose, and out the other side.

I hear people saying that the world will never be the same again. I don’t know, how much changed because of the Spanish flu? But some things may change.

Perhaps our existing school and university system. Everyone is about to learn about studying and teaching online. It is intrinsically cheaper and more convenient; are we going to go back to the old way?

If we learn online, we will be able to choose the best course and the best teacher for each subject; that’s surely a big advantage. Hard to go back after that to our little silos. The costs of the old way were already spiraling beyond sustainability anyway.

Globalization and open borders are another likely casualty. We now see the need to keep essential supply chains at home, or at least with reliable allies. We see the need to have doors on our countries as well as on our homes.

Some have said the EU has already, in effect, fallen apart, as the countries in the Schengen zone have closed their borders to each other.

Some worry about governments expanding powers to handle the emergency, and whether that power will be easily relinquished later. On the other side of the ledger, a lot of government regulations suddenly look unnecessary and annoying.

This should also give a boost to the practice of working from home; everyone will have developed systems to do it, and had some practice. As with schools and universities, it is a cheaper and more convenient alternative; for workers and for businesses.

If we begin more often to work at home, this diminishes the value of living in cities. In which real estate was already becoming insupportably expensive.

Cities now also suddenly seem unhealthy. They are virus sinks.

Cities may begin to shrink. This will not help their housing markets, of course.

With the value of the internet demonstrated in this crisis, there may be a push to guarantee internet access to everyone, as we now consider it essential that everyone have access to electricity and running water.

And, as I noted previously, we are getting to stress test our societies and governments. We may clean house as a result.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 22, 2020 11:49

Another Pandemic Altogether

It is hard, in the midst of a historic pandemic, to write about anything other than the coronavirus. About which, unfortunately, I have no expertise to offer. But there is another virus, more dangerous, to which I have recently been exposed.

The subject my student is studying in her grad program, “Critical Pedagogy,” is a Marxist take on “constructivism.” It is the dominant philosophy now in all branches of “education,” from kindergarten through the ed schools, up to doctoral level, and far enough afield from there to include the language schools.

The basic premise is that knowledge is “constructed,” as opposed to discovered. Learning is, in the words of the present paper, “a process of collaboratively constructed knowledge.”

It follows that the teacher cannot actually teach anything. The paper criticizes traditional education for seeing students as “empty agents who receive knowledge from teachers.” An image often used is of the learner as a passive empty glass that the teacher, in the bad, old way, is filling up with knowledge.

This sounds good. But that is not how traditional education worked at all. Genuinely traditional education means the Socratic method—that is, asking questions to provoke the student to think, rather than feeding him facts. And Bacon’s scientific method: don’t take anyone’s word for it, do the experiment. Nor is this true only of the West. Confucius said, “I show a student one corner of the problem. If he cannot discover the other three corners himself, I have no more I can do for him.” His collected sayings, which we call “The Analects,” model this method. Nothing is said plainly; they all require consideration and interpretation. They are hints.

Jesus did the same, of course, with parables. He might well be ranked as a third great teacher.

Traditional education used this method precisely because they did not see truth or reality as an arbitrary construct. Plato, our source for Socrates, understood all knowledge as innate; we are born with it, or we could not recognize it in the sensory world. Accordingly, all the teacher need really do is jar the memory.

But even without this “Platonic” view, which Confucius clearly shared, so long as objective reality exists in any form, the teacher’s job remains to teach the student how to reason, how to learn, how to discover things for himself.

Traditional education, accordingly, taught debate, logic, rhetoric, parliamentary procedure, mathematics, and the scientific method: ways to think, ways to arrive at knowledge.

Constructivism yanks this rug right out from under the enterprise. If, as it asserts, all truth is arbitrary, there is nothing at all to teach or to learn. One simply decides what one wants to be true. No role here for education at all. No role for anything but pouring things into empty vessels—indoctrination.

For of course, in a classroom, each individual student cannot be allowed to make their own reality; those realities will conflict. So what is one to do?

Here’s where the “collaborative” bit comes in. The stock constructivist response is that everyone in class must agree on the same reality.

This is at best a stopgap—the students will, sooner or later, need to leave the classroom, and their shared reality will not conform with the equally arbitrary shared reality of any given larger group.

But even within the class, on what basis, given that all realities are arbitrary, is one proposed reality to be preferred to another? On what basis does one come to a consensus?

Critical pedagogy, and constructivism generally, masks this with an implicit appeal to democracy: it is decided by majority vote. This is, in philosophical terms, the ad populum fallacy: majority opinion is no indication of truth. But even that is irrelevant; if truth itself is arbitrary, the only basis for preferring majority over minority truth in the first place is might makes right: the majority has the power to suppress the minority if it dissents.

It is significant that constructivism never gives any thought to parliamentary procedure or to how consensus is to be arrived at. For after all, if all realities are arbitrary, there is simply no room for debate. The biggest bully gets their way.

Of course, in a real constructivist classroom, it is the teacher who has ultimate power. It is the teacher’s chosen reality that will prevail, under the guise of “consensus.”

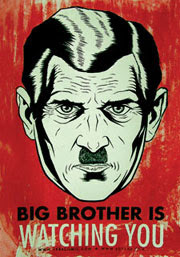

One begins to see why constructivism in various forms has become so popular among teachers. It gives them the most absolute power possible over the students in their class, and imposes no actual obligations on them to do anything they do not choose to do. It makes the classroom model a totalitarian dictatorship of Orwellian dimensions.

It is interesting, and alarming, that the essay my student was assigned was actually authored by two professors at the Islamic Azad University in Iran. That suggests how pervasive this ideology is: it dominates even in a supposedly Islamist university in a supposedly theocratic state.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 22, 2020 06:16

March 21, 2020

A Journal of the Plague Year

I recommend Scott Adams’ YouTube channel for the best current take on the crisis. Adams is reassuring.

Adams suggests the US government may be talking less hopefully about chloraquine than the known facts warrant.

They may not have enough of it yet. They do not want patients beginning to demand chloraquine while they are rationing it to the cases where it seems most needed.

And there is the risk that, if they knew there was something like a cure, people would prematurely start breaking quarantine and lockdown, swamping the system.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 21, 2020 15:12

Critical Pedagogy and Jack the Giant Killer

One of my graduate students is taking a course in “Critical Pedagogy.”

The name does not reveal the true subject: it is the systematic assertion that teachers should devote all their in-class efforts to promoting revolution against the system, rather than teaching the assigned subject. What Jordan Peterson refers to as “cultural Marxism.”

My student cited a typical thesis in this subject: “Jack and the Beanstalk” told from the perspective of the giant.

Interesting, because I only recently saw the same trick in an assigned textbook for young learners: “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” from the perspective of the wolf.

This reveals a core appeal of such ideological approaches. They make it easy to write a thesis. You just take any classic text, and do a “feminist view,” or a “Freudian view,” or a “structuralist view” or whatever. It is purely formulaic, mechanical. It takes no talent or insight; it is like filling in the blanks on a form.

It also explains why these ideological fads fade: after a while, you need a new ideology, or you run out of thesis topics. They come, they go, and no new knowledge nor insight into the works is generated.

The idea behind reading “Jack and the Beanstalk” from the giant’s point of view is no doubt to subvert cultural norms and show the violence inherent in the system. Jack, after all, is a murderer and a thief.

But this is working from the false assumption that Jack was ever considered a hero.

There is nothing new or transgressive about seeing an apparent villain in a fairy tale as a hero, as the suggested thesis topic does with the giant. This is the basic plot, for example, of “Beauty and the Beast.” “Rumpelstiltskin” hinges on an apparent hero turning out to be a villain. The tales school us in trying to see things from all perspectives.

We see an example in “Jack and the Beanstalk” itself. A pedlar trades five beans for Jack’s cow. We as listeners of course assume, as Jack’s mother does, that he is a con artist. But it turns out the beans really are magic. He was a good guy after all.

Is the tale prejudiced against giants?

Clearly not; the giant’s wife, the giantess, is a sympathetic character.

So it is obviously part of the original story that one is supposed to see things from the giant’s viewpoint as well as Jack’s. Jack’s moral position is meant to be ambiguous. He is a “trickster,” a figure familiar in folklore of all lands.

Why there are such stories, in all cultures, is an interesting issue. It might make a good thesis.

It might also make a good thesis to consider the moral questions raised. They are not simple. Is Jack justified in stealing because of his need? Is Jack justified because the giant is a cannibal? Is the giant’s wife betraying her husband, or is it her duty to protect a stranger? What determines the real value of a bean or a cow? On what grounds can we judge a voluntary exchange either fair or unfair? Is Jack justified by self-defense in killing the giant pursuing him? Even though the giant is trying to recover stolen property?

All fascinating questions, that the story is skillfully and deliberately raising.

All missed by this “critical pedagogy approach,” which comes at the tale from the novel and rigid perspective that the giant must be supposed to be right in whatever he does.

Because, hey, he is the giant, he is rich and powerful. And might apparently determines right.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on March 21, 2020 07:11