Stephen Roney's Blog, page 230

July 25, 2020

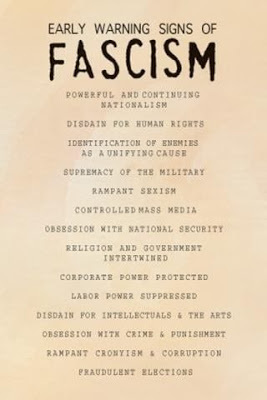

Early Warning Signs of Fascism

A left-tilting friend has posted on Facebook a familiar poster of “Early Warning Signs of Fascism,” as a warning against Donald Trump.

Our obvious first question ought to be, who says these are the first signs of fascism, and how credible is their opinion? As it is a poster, it offers no evidence or argument; just assertions. Nobody who has been taught how to think, or figured it out for themselves, should take this at face value.

Nobody seems to give a source; they seem to just see it in print, and so assume it must be true.

Such people would make ideal acolytes in an actual fascist state. A similar poster might list “Twelve Harms Done by the Jews.”

Some attribute it to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The USHMM denies this; they once sold the poster in their gift shop, but, interestingly, without explanation, have pulled it.

Scopes tracks it down to Laurence Britt, a businessman and amateur historian.

As an appeal to authority, this is pretty weak.

Among academics, there is really little agreement on what constitutes “fascism.” “Fascist” positions and policies are all over the map, and seem to show no core ideology.

Let’s look at Mr. Britt’s list.

1. Powerful and continuing nationalism.

On this at least, I think there could be general agreement. This is one reason fascism is so incoherent: the perceived interest of one nation will not be the same as the national interest of another state, so that fascisms in different countries can hold opposite views on any given issue. German fascism was, historically, in opposition to Austrian fascism, and for a time with Italian fascism. Similarly, on almost any given point of policy, different national fascist parties can be opposed.

But is Trump’s administration fascist by this measure? While it is nationalistic in comparison with other recent American regimes, it surely does not stand out as nationalistic in either world or historic terms. To the contrary; the US, and the West in general, have been moving in the opposite direction, towards “globalism.” Trump looks like a relatively mild popular reaction against this, but bringing the US closer to alignment with the world and historical norm. The same could be said of various “nationalist” movements in Europe.

This nationalism fails the stated test of being either powerful or continuous.

Nominally communist or socialist regimes are currently the most nationalistic: North Korea, China.

2. Disdain for human rights.

This seems fair as a description of fascism. Mussolini was openly opposed to liberal democracy as decadent, and to the doctrine of individual rights and individualism. The very symbol of the fasces emphasizes the group over the individual. Hitler’s Nazis obviously honoured no right to life.

Yet does this describe the Trump administration? What human rights has it opposed? Rather, Trump has been fairly vocal in supporting the right to life, the right to bear arms, freedom of conscience, and freedom of speech.

In world terms, the US is probably here too the one country furthest from fascism. Within the US, the current left is plainly more fascist than the right: they follow the fascists in emphasizing the group over individual rights. For an obvious example, they currently embrace the slogan “black lives matter,” and are violently opposed to the slogan “all lives matter.”

3. Identification of enemies as a unifying cause.

This is not obviously a core fascist characteristic; rather, it is a universal law of politics and social life. You can rally support to yourself by uniting the public against some scapegoat or imagined enemy. Animal Farm or Lord of the Flies offer literary examples.

And, at the same time, in many circumstances clear identification of the enemy can be a necessary and a deeply moral act. This is what Churchill did, in pinpointing Hitler as the enemy; and again in warning of an iron curtain falling on Europe. It is what the police do when they identify a murderer, and put up warnings in the post office.

Trump seems conspicuous in not playing this enemies game. He may berate this opponent or that, this group or that, and, the next time the matter comes up, make a point of praising them. Rather than rallying rage against an imaginary enemy or a scapegoat, he seems to do this as a negotiating tactic.

The classic current example of a group seeking to unite on the basis of a purely imaginary common enemy is “Antifa.” It is embedded in their name.

4. Supremacy of the military.

This is not true of Hitler’s Germany. The Nazis built up the armed forces, but this is not the same thing. They were also in ongoing conflict with the officer class. All soldiers were required to take a personal oath to Hitler. That’s subjugation, not supremacy. The military also exerted no authority over the civilian population.

Trump’s relationship to the military seems to be about the same as that of any other president. Funding of the military has gone up in real terms, held steady in GDP terms, and is broadly in line with historic trends.

5. Rampant sexism.

This is anachronistic. The term “sexism” was coined only in the Sixties. Relations between the sexes were not the hot button issue then they are today.

But the fascist record is not broadly one of opposition to what today would be called feminism. The very first point of the Manifesto of Piazza Sansepolcro, often considered the founding event of Italian fascism, was “vote and eligibility for women.” Mussolini wanted to require that a minimum proportion of the Italian legislature be women. His government prohibited firing women because of pregnancy or maternity leave. G.A. Chiurco wrote, in 1935, "The fascist state can't conceive the woman locked in her house."

The Nazi record in Germany was different. They tended to emphasize the importance of motherhood, for sustaining the race. But they were also comfortable with women, like Leni Riefenstahl or Hanna Reitsch, in high public positions, running concentration camps, and in the military.

6. Controlled mass media.

This seems misplaced on a list of “early warning signs.” Fascists did not have the means to control the media before the came to power. They were active and enthusiastic journalists; Mussolini himself was a journalist. But this does not amount to control.

Fascist regimes certainly took control of mass media as a standard practice once they came to power.

Already in power, Trump has made no moves to control the media.

While the “legacy media” does seem to move in lockstep, this seems to be a case of a cadre, similar to the early fascists, of active and enthusiastic journalists. Significantly, they actually seem to be united against Trump.

7. Obsession with national security.

As a description of the Italian Fascist or the German Nazi regimes, this seems off point. Their concern was not with defending their borders, with security, but with invading other countries. The charge of “obsession with national security” could more reasonably be levelled against Churchill or De Gaulle.

Is Trump interested in invading other countries? It seems the reverse; he seems to be making efforts to pull troops back from foreign involvements.

8. Religion and government intertwined.

This again does not seem to be the proper phrasing. After all, religion and government are constitutionally intertwined in the United Kingdom, modern Germany, or in the Scandinavian countries, without these being considered fascist countries. It would be better to say “religion subservient to government.” As Mussolini put his essential creed: “everything within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.” It is a matter of who gets to call the shots.

There is no sign of Trump trying to make religion knuckle under to the demands of the state in America. The obvious example of this in the world today is China.

But it is also a broad tendency on the American left, not strong on recognizing conscience rights.

9. Corporate power protected.

As phrased, this is false. In fact, Fascist Italy nationalized more industry than any other nation but the Soviet Union. While Nazism or fascism left other corporations standing, and even protected their markets and profits from competition, they removed all power from their ownership or management. Corporations allowed to remain in business were treated like arms of the state, obliged to do what the government required. This was the fascist understanding of socialism.

Trump could be accused of doing this in a small way by invoking the Defense Production Act; but this is recognized as legitimate in any democracy in a state of national emergency—just as the French army commandeered the taxis of Paris for the Battle of the Marne.

More generally, Trump has been aggressive in reducing government regulations on business. This increases the decision-making power of corporate ownership or management, and, at the same time, reduces their protection from competition. It is the opposite of the fascist programme.

The classic contemporary example of a regime operating on this fascist basis is China.

10. Labour power suppressed.

The fascist treatment of labour or the corporations was parallel; one cannot have been “protected,” and the other “suppressed.” The Nazis made protecting and advancing the rights and interests of the workers one of its main policy objectives; but the unions, like the corporations, became organs of government. Workers were expected to do what the government ordered.

There is no parallel with the Trump administration; except that Trump, like the fascists, claims to make the interests of working people his primary concern. The modern parallel is again the Chinese regime, in terms of unions becoming arms of the state.

11. Disdain for intellectuals and the arts.

This is the biggest howler on the list. Fascism began as an artistic and intellectual movement, which then moved into politics. Gabriele d’Annunzio, poet, journalist, and playwright, set up the first fascist regime, with himself as Duce, in Fiume. Fascism as an intellectual movement had clear antecedents in Nietzsche, Darwin, and Marx. It was more or less the application of the currently fashionable intellectual trends to practical politics. William L. Shirer, in Germany at the time, noted that the Nazi party was especially strong and popular on university campuses.

A significant number of prominent intellectuals and artists of the day supported the fascists: Ezra Pound, Martin Heidegger, Luigi Pirandello, Knut Hamsun, Thomas Wolfe. Hitler, of course, considered himself an artist; Mussolini wrote and published short stories.

Trump’s opinion on intellectualism and the arts is less clear. He has a reputation as a vulgarian. He does oppose tearing down statues.

12. Obsession with crime and punishment.

The Nazis, and Mussolini’s blackshirts, were characterized in their earlier days not by any appeal to law and order, but by criminal activities and brawling in the streets. Rather than a government of settled laws, fascism embraced the “leadership principle.” It gave license to some to freely do things that would have been crimes in most other countries. Rather than calling for social peace and order, it called for “Mein Kampf” and the greeting “Seig Heil.”

Concern with crime, and with public order, is a characteristic instead of traditional conservatism. Which, Shirer noted, was the one group consistently opposed to fascism.

Trump does not seem to be in favour of rioting or gang violence. This puts him in opposition to fascism. The obvious modern advocates and practitioners of Storm Trooper tactics are groups like Antifa and Black Lives Matter.

Trump is also no hard-liner on crime and punishment. He often boasts of his “prison reform,” which moves in the opposite direction.

13. Rampant cronyism and corruption

This is also misplaced. Fascism came to power in Italy or in Germany largely on a promise to stamp out cronyism and corruption. Mussolini promised to “make the trains run on time.” Hitler ran on an image of personal incorruptibility. The new ideal of the national good and the good of the whole was supposed to end the perceived rampant cronyism and corruption of the times.

Fascism turned out not to be effective in this regard, and fascist officials, given the opportunity, were indeed often corrupt; but it seems more accurate to say that it failed to prevent cronyism and corruption than that it caused it.

Is Trump guilty of rampant cronyism or corruption? Charges of cronyism and corruption are levelled against most administrations; notably against Joe Biden, the certain Democratic nominee to run against him.

14. Fraudulent elections.

Fraudulent elections are significantly more common than are regimes we would generally call fascist. They are also the norm in communist or most Third-World regimes. And Hitler first came to power in what seems to have been a reasonably fair election.

Voter fraud and fraudulent elections are an eternal problem, but not one associated especially with either fascism or Donald Trump. “Russian collusion” turned out to be an unsubstantiated allegation.

The Republicans routinely charge Democrats of election fraud; the Democrats routinely charge Republicans. No doubt sometimes they are right.

Conclusion: Donald Trump has nothing to do with fascism. The case is stronger for the modern American left, and especially strong for seeing the current government of China as, essentially, fascist.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 25, 2020 09:49

July 24, 2020

GPT-3

You may have heard some hype on GPT- 3. It’s a new Artificial Intelligence program based on the web as corpus. You can type in almost anything, and it will respond with something appropriate. You can ask it to write a term paper, or translate a text from another language, or write a blog post, or a poem, or a story.

Okay, don’t get too excited--or alarmed. It can do this in a superficial sense, but what it generates is still, inevitably, nonsense. Making it only an amusing toy.

For example, asked to write an opinion piece, its logic is incoherent.

The human prompt is shown below in bold, then GPT-3’s response:

The following is a blog post from Slate Star Codex about the value of free speech and civility in a democratic society.

Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night

By Scott Alexander

There’s a concept that comes up often in debates about free speech called “shouting fire in a crowded theater”. The basic idea is that you can’t just say whatever you want whenever you want – especially if it’s likely to cause panic. And the reason for this is obvious: panic leads to violence, and violence hurts people. If you are causing panic, then your right to free speech ends where the other person’s right to not get hurt begins.

But this isn’t really true. If shouting fire in a crowded theater were illegal, then there wouldn’t be any actual fires in theaters, would there? How could there be? If everyone knew that shouting fire would get them thrown in jail, then they’d all keep quiet when they smelled smoke – and thus there would never be any fires at all. The only way someone could shout fire is if they were lying – but lying is also illegal. So if shouting fire in a crowded theater were illegal, then theaters would never burn down, and no one would ever die from a fire.

The way I see it, the phrase “shouting fire in a crowded theater” should be replaced with “yelling ‘there’s an angry mob coming with torches and pitchforks’ in a theater”. This doesn’t sound quite as catchy, but it has the advantage of being true. And this matters because the whole concept of free speech is based on people getting the facts right. If you’re going to shout fire in a crowded theater, then you need to actually have seen a fire – not just heard about one from someone else. You need to have checked that there really is a fire before you warn everyone else that there’s a fire. Otherwise you’re just causing panic for no reason – and that’s not free speech, that’s just yelling “boo” in a crowded theater.

Asked to write a short story, it cannot offer a coherent plot.

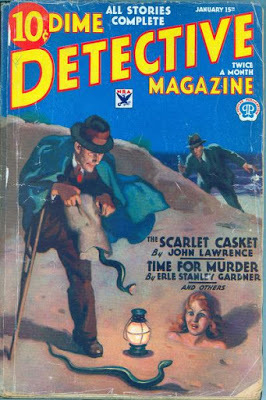

Below is a screenplay for a film-noir hard boiled detective story by Raymond Chandler about the boy wizard Harry Potter:

“Harry Potter”

By Raymond Chandler

Harry Potter, Private Eye.

Scene: A small dingy office, early morning, furniture of the Salvation Army store variety. Sordid atmosphere. Harry Potter, in ratty tweed suit, unpressed shirt, and unshined shoes, sits behind the desk looking haggard, rumpled, and embittered. In one corner of the office a torn shade rattles at the wind gusts outside. Harry has one long index finger on the butt of a .38 and he broods over a photograph. The photograph shows a gorgeous blonde wearing an evening gown. She is holding a cocktail in one hand and looking pensively at a cigarette in the other. A tear adorns her cheek. Harry looks at her for a long moment, sighs, then puts his gun down and stands. He straightens his clothes, scratches his head, then with more resolution turns around, picks up his pistol, and leaves the office. He passes through the front room and looks out the dirty window. An old woman is washing the sidewalk outside with a mop. A young man in a double breasted gray suit is leaning against the building. Harry sighs again and goes out the door. He walks up to the young man and without ceremony punches him in the jaw.

Asked to write poetry or a song lyric, the lines do not cohere to tell a story or to make a larger statement, and there is no consistent rhythm and no rhyme.

Below is a pop song by Taylor Swift about the boy Wizard Harry Potter.

“Harry Potter”

By Taylor Swift

Harry’s got glasses

He’s got those bright green eyes

Girls are always screaming

‘Cause he’s got that Potter hair

Even when he’s super stressed

He’s still got those supersonic cheekbones

I’m not surprised they made a movie

‘Cause I’d watch him anytime

Oh, yeah, Harry, baby, you’re my favorite character

I’d walk a thousand miles

To get to see you and

Harry, Harry, you’re so fine

My girly parts all tingle

When you smile that smirk

I’d love to be your girl

No rhythm, no rhyme, no coherent thought. Kind of like modern poetry, actually.

But one thing it can do, and it is kind of creepy.

Say what you want in standard English sentences, and it can write code. Any kind of code.

https://twitter.com/i/status/1282676454690451457

The code that it puts out may not be elegant or efficient. But still, for most people’s needs—writing code may soon be no more or less than writing proper, unambiguous English.

That may kill an entire profession, that until yesterday was the hottest and fastest growing around.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 24, 2020 13:22

The Case for Hydroxychloraquine

https://www.foxnews.com/media/hydroxychloroquine-could-save-lives-ingraham-yale-professor

https://www.newsweek.com/key-defeating-covid-19-already-exists-we-need-start-using-it-opinion-1519535

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 24, 2020 12:15

July 23, 2020

Are the Schools the Root of All Evil?

Scott Adams is the cartoonist who does “Dilbert.” He has nothing to do with education. Today, however, on his YouTube channel, he declared his conclusion that all our current problems, which seem to him as to me to be spinning out of control, are really just one problem: teachers’ unions.

As I understand him, he makes two points. First, the mobs out tearing down statues and looting are demonstrating that they have not learned how to think: at best, their actions are not addressing their real problems. They seem like children having a tantrum, smashing their toys, demanding that some adult step in and make everything right. If the problem is racism, as they commonly say, nothing they are doing is addressing the problem.

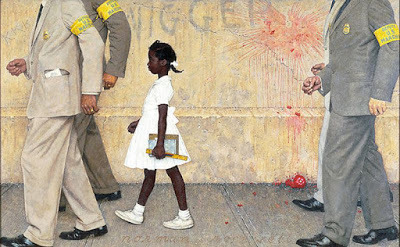

Second, all the current anger over “racism” is deluded. As the system is currently set up, a young black man with a good education actually has better opportunities than a young white man. Government and corporations are climbing over one another to hire him. Therefore, the problem is education—getting those young black men the skills to make then hireable. Better schools, especially in poor and in black neighbourhoods, would fix this supposed “racism.”

And by the way, didn’t we always think this? Remember desegregation? That was primarily desegregation of schools. Getting the black kids into the same schools as the white kids was supposed to end the problem. It was deficits in education that were holding blacks back.

Instead, now the schools are failing black kids and white kids equally.

And Adams sees all attempts to make the problem better blocked by teachers’ unions.

So, he concludes, the solution is to ban the teachers’ unions.

I agree with him that the teachers’ unions should be banned. I agree that if they were, education would quickly improve, and the costs would go down.

But I also think the problem is bigger than he realizes. Get rid of them, and we could experiment with other approaches. But we would also have to get rid of teacher certification, and the teachers’ colleges. Because, given the current state of educational theory, we still would have no idea how to make schools better. The academic field of “education” is bankrupt.

For that matter, all academic fields in the social sciences, and now most of the humanities, are bankrupt.

The deeper problem comes from the consecration of science as our new religion, beginning in the nineteenth century, and reaching the schools in the early twentieth century. On the model of science looking at the physical world, humans were redefined as objects. And schools were redesigned as factories.

I agree with Adams that education is critical. The essential task of civilization is education: passing on the culture to the next generation. Our system of education is clearly not now passing on the culture. This means, within a few short generations, civilizational death. And we have been failing to pass on the civilization for at least a couple of generations now. It should be no wonder that suddenly all the systems seem to be failing. The civil service can no longer be relied upon; the press can no longer be relied upon; the church hierarchy can no longer be relied upon; the academy can no longer be relied upon; the courts can no longer be relied upon; the parliaments can no longer be relied upon; even things like dictionaries are no longer reliable, as the meanings of words change rapidly for political advantage. Everyone is suddenly pursuing what they see as immediate self-interest.

It is also striking how almost everything we see now in the media, in academics, in civil discourse, is based on simple logical fallacies. Nobody indeed knows any longer how to think; for nobody is taught how to think in the schools—the one skill everyone needs.

But since people were redefined as objects, the implicit assumption must be that thought itself is impossible, or purely an illusion. Machines can’t think.

Nor, of course, is there any longer such a thing as right and wrong. There is only wanting, and then trying to get.

There is only looting or smashing things.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 23, 2020 16:45

July 20, 2020

A Message from Singapore

"Americans - why is the mask thing even an issue? It’s not political. It’s for the safety and health of all. Stop being idiots and wear a damn mask! Everyone does in the developed East/Southeast Asian countries - it’s the law and 99.99% of the people are happy to comply. Guess what - the curve is flattened and cases have dropped by a large amount in the developed countries here (SG, TW, NZ, MY, TH, JP, KR, HK, even your worst enemy CN) big time. Day to day life is *almost* back to normal. Restaurants and bars are open, shops and salons are open, schools are open/kids are in school, amusement parks and most playgrounds are open, hospitals have capacity for the sick, not too many are dying. We all wear masks here and it works! Why are you letting the virus defeat you?"'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 20, 2020 16:43

Good News on Coronavirus?

In his profoundly understated English way, Dr. Joseph Campbell seems to be excited by this new research.

It suggests that immunity to COVID-19 lasts at least seventeen years.

It moreover suggests that some portion of the population is already immune.

This seems to be from prior exposure to some other virus that caused no or trivial symptoms.

Put this together, and it suggests that 1) an effective vaccine stands a good chance of rendering this vuris extinct. 2) we may be closer to "herd immunity" than we realize. possibly the maggic number is now as low as 20% for new infections. 3) there may be a natrural and safe vaccine already out there, just like cowpox was for smallpox, if we can just figure out what the prior infection was that caused this common immunity.

From a BBC story:

"Most bizarrely of all, when researchers tested blood samples taken years before the pandemic started, they found T cells which were specifically tailored to detect proteins on the surface of Covid-19. This suggests that some people already had a pre-existing degree of resistance against the virus before it ever infected a human. And it appears to be surprisingly prevalent: 40-60% of unexposed individuals had these cells."

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 20, 2020 16:42

The Parable of the Wheat and the Tares

The Devil sowing tares.

The Devil sowing tares.Jesus proposed another parable to the crowds, saying:

“The kingdom of heaven may be likened

to a man who sowed good seed in his field.

While everyone was asleep his enemy came

and sowed weeds all through the wheat, and then went off.

When the crop grew and bore fruit, the weeds appeared as well.

The slaves of the householder came to him and said,

‘Master, did you not sow good seed in your field?

Where have the weeds come from?’

He answered, ‘An enemy has done this.’

His slaves said to him,

‘Do you want us to go and pull them up?’

He replied, ‘No, if you pull up the weeds

you might uproot the wheat along with them.

Let them grow together until harvest;

then at harvest time I will say to the harvesters,

“First collect the weeds and tie them in bundles for burning;

but gather the wheat into my barn.” – Matthew 13.

Yesterday’s mass reading began with this parable.

Few ever seem to notice that parables always include something that, on the surface, makes no sense.

Any amateur gardener should see it. Nobody allows the weed to grow in their garden or their field until harvest. Weeding is the crucial chore in gardening. If they do not take over altogether, untended weeds will stunt the crop. And make it difficult to harvest.

The gods must be crazy.

The householder does not want the weeds pulled up because his servants might not be able to see the difference between weeds and wheat. Yet he assumes that the eventual harvesters will have no trouble doing so: first they will collect the weeds for burning, then gather the wheat. This is aggressively illogical.

When we see such things, we should assume we are being required to take a closer look; things are not as they appear.

Jesus gives a partial explanation to his apostles:

“He who sows good seed is the Son of Man,

the field is the world, the good seed the children of the kingdom.

The weeds are the children of the evil one,

and the enemy who sows them is the devil.

The harvest is the end of the age, and the harvesters are angels.

Just as weeds are collected and burned up with fire,

so will it be at the end of the age.

The Son of Man will send his angels,

and they will collect out of his kingdom

all who cause others to sin and all evildoers.

They will throw them into the fiery furnace,

where there will be wailing and grinding of teeth.

Then the righteous will shine like the sun

in the kingdom of their Father.

Whoever has ears ought to hear.”

So the wheat is the good people, and the weeds are the bad people, and the field is the world. And the question addressed is, why does God allow the evil to prosper? Why not just strike them with a lightning bolt?

It cannot be that his servants cannot identify them. For who are his servants in this parable? Not mortal followers: those are the good seeds. The servants must be angels; he identifies them as angels at the harvest. There is no question that God knows all the time who the evil people are. There is no question that he has the power to tell the angels who they are.

But doing so, it would seem, would “uproot the wheat along with them.”

How so? It cannot be in the conventional sense; it cannot be in the literal sense. It is that the wheat cannot be wheat without the weeds.

The weeds are “all who cause others to sin and all evildoers.” The evil will thrive in this world, as weeds will in an unweeded field. If they did not, there would be no temptation for anyone to do evil.

So the good can only be the good, can only grow to be wheat, if they are exposed to and can survive the weeds without becoming weeds. The point is that with souls it is the opposite of with wheat.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 20, 2020 11:48

July 19, 2020

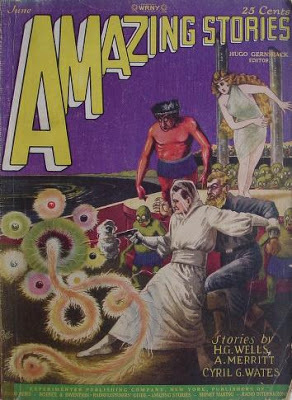

Pulp Fiction

Like a dog intent on a squirrel up a tree, linguists have been trying in recent years to figure out just how it is we read. Their conclusions, predictably for the social sciences, are either outright wrong or common sense. Nevertheless, the obvious facts they have stumbled over in their charmingly pedantic way offer some useful tips for writers.

They find we do not read letter by letter, or word by word, or even sentence by sentence. We no doubt do as we need to, but we also read by pattern recognition. We anticipate what comes next.

A famous example is the phrase:

Valleyfield in the

the spring.

Most people will read that without the second “the.”

Or this example:

It deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe

Who knew? Besides everybody. But have we as writers thought through what this means?

Kintsch and van Dijk (you can’t beat the Dutch as academics; in my experience, they stand a half a sliced door above the rest) suggest that this is also true at higher levels: at the level of the paragraph or, in editing terms, at the structural level.

This is the appeal of genre writing. If writing is a tool to communicate, genre writing is the best writing, because the predictability allows us to dispense with the more mechanical parts of reading, and concentrate on the meaning.

If we are reading a medical paper, for example, that is following the conventions of that form, we can extract what we need efficiently. Or a technical manual; or a news story. We can read it at a higher cognitive level; less of our attention needs to be occupied by annoying little individual words and letters and sentence constructions.

This is the opposite of what most writers, most editors, and most writing instructors currently profess. Recall George Orwell’s famous advice, in “Politics and the English Language”: “Never use a word or phrase you are accustomed to seeing in print.” We look down our bespectacled noses at genre writing. Genre writing is for hacks and dummies. Romance novels, cowboy stories, detective novels, comic books. Pulp fiction.

There’s a collection online, at the Internet Archive.

But myths are also highly generic—more so that these modern forms. And myths express the deepest thoughts of most cultures. Poetry is more generic, has more rules, than prose; Shakespeare preferred the sonnet, a highly mannered medium. And he was a decent writer. Classical Greek tragedy, surely as deep as any writing, followed strict rules approaching a ritual performance, Aristotle’s “three unities.” For a more prosaic example, philosophical writing is always concerned with clearly defining terms, and then using them consistently. Each philosophical essay may amount to its own genre, but it follows strict rules so that the thought is not obscured by any unnecessary novelties.

That heavily generic writing also works for low-level readers simply shows that its communicative value is absolute. For the marginally literate, or for children listening to a fairy tale, it works for all the same reasons that it works with Aristotle and Shakespeare: it allows them to assimilate the information efficiently, to participate in the story or the emotion or the idea, without getting bogged down by the mechanics of reading, in which they may be unskilled.

And for all the rest of us, generic writing is the most enjoyable, for exactly the same reason. We can get fully engaged in the story, and with our own imagination, without being distracted.

Introducing some unnecessary novelty is like letting the boom microphone appear in the shot; it kills the willing suspension of disbelief.

Orwell is close to having a point, with his cliché against cliché. The problem is not the use of a stock, familiar phrase. The problem is that, when a phrase becomes too familiar, it starts being resorted to unthinkingly, and so without meaning or even incorrectly. That is what grates, and what impedes communication. Every night is not “a dark and stormy night.” But if you want to tell the tale of a haunted house, then it ought to be.

Every once and again, some writer comes out with something generic and good, violating all the academic norms by following all the norms, and makes a big splash. That’s what JK Rowling did with Harry Potter. That’s Stephen King. That’s JRR Tolkien and Lord of the Rings. That’s Star Wars; that’s Indiana Jones. These do not experiment with or violate norms, or treat them ironically; they follow them well. And readers appreciate it.

For a narrative, genre allows us to enter more fully into the fully imagined world.

The fact that “sophisticated,” “serious” writers do not write this way goes a long way towards explaining why reading has become less popular. We have forgotten what good writing is, and are instead self-righteously scribbling inferior stuff, interesting only to other writers. Good writing is, by definition, what is easy and enjoyable to read.

We have stumbled into this because, beginning at about the start of the 20th century, certainly by the 1920s, we came to idolize science as the crown and measure of all things. Accordingly, we got the notion that good writing should be like science, or like technology. James Joyce declared himself “the greatest engineer who ever lived.” Strunk and White compared an essay to a machine.

So literature should, like technology, be undergoing constant improvement. It must not rely on the tried and true. It must, like science, always be “experimental.”

Art does not work like that. That makes as much sense as inventing your own alphabet. Experiments might be useful in the writer’s private study, or among artists, but art as a whole does not progress. It is tied to eternal truths, eternal truths of human nature, and eternal things do not change. The tools of communication are relatively incidental, and the only issue is that they are clearly comprehended by both author and audience. There is a point at which that cannot be improved upon, and it can never be improved upon unilaterally. “Experiments” cannot work in actual communication, because any unexpected novelty reduces communication for the reader.

There may be times at which you want to inhibit communication in order to make a point; to jolt the reader out of a familiar and false way of thinking. But this will be the exception, not the rule.

James Joyce is a magnificent writer in detail. Nevertheless, he is unreadable.

Genre writing is the way to go.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 19, 2020 07:41

The Iconoclasts Zero in on Catholic Churches

https://aleteia.org/2020/07/17/catholic-churches-across-u-s-suffer-week-of-vandalism-and-arson/

https://www.ncregister.com/daily-news/satanic-symbol-painted-at-church-in-new-haven-parish-where-knights-of-colum

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 19, 2020 05:39

July 18, 2020

A Chronicle of China Dying

Things are seldom what they seem.

Things are seldom what they seem.What is China up to?

There is much talk these days of “Thucydides’ trap,” the idea that a dominant power inevitably comes into conflict with an emerging power; and so the US must inevitably go to war with China. Some go further, and suggest that China will inevitably overtake the US for dominance, and within our lifetimes.

That is not what I see happening. To begin with, by this thesis, it should be the US that is getting bellicose. I see China rattling the sabres, not the US. Further, if China’s rise is inevitable, the last thing China should want to do is to take any risk of provoking war—a war now is the only thing that might stop them, by reshuffling the deck.

Instead of a rising power, I smell dead meat.

This smells instead to me like what happened with Nazi Germany, and what happened to the Soviet bloc. Neither of which fit into Thucydides’ little mouse trap. If anyone ever did.

To my mind, and my reading of history, a war is at least as often the thrashing about of a power that feels itself in trouble.

Like Austria-Hungary, the relatively impoverished and senile power that actually started World War I. Or the Confederate States of America, an agrarian slaveholding society seeing itself threatened by the growing industrialization and the growing population of the anti-slavery North. Or Japan entering World War Two, calculating that they needed to grab a source of oil or soon die. Or Hitler invading the Soviet Union, probably for the same reason.

But as for Hitler, let’s back up a few years. Hitler’s government, in the 1930s, performed what looked like economic miracles for a prostrate Germany. Just as China’s government seems to have done since 1990. Just as Stalin seemed to do for Russia in the 1950s. Unfortunately, Nazi Germany in the 1930s was an economy run as a Ponzi scheme, printing money and hiding the real books, and Hitler understood that he could only keep the whole thing from collapsing by, first, confiscating the wealth of the Jews, and, second, invading and confiscating the wealth and labour of other lands. Czechoslovakia, then Poland, then… So war was inevitable; it was baked in the cake.

Outwardly, everyone seemed to think the economy of the Soviet Bloc was growing and competing with the West right up until the year it fell. Before it suddenly fell, many of not most Western intellectuals assumed the Soviet Bloc was on the brink of supplanting the West. Even such a right-winger, and such a savvy right-winger, as Henry Kissinger, who when he became Secretary of State compared himself to Metternich, as someone charged with trying to sustain a declining empire.

Yet the Soviet Union fell, apparently, because the government ran out of money. They could no longer afford to try to control or financially support their satellites. They could no longer afford to keep up with the USA in an arms race. And once the dust settled, the Russian economy was revealed to be significantly smaller than the economies of such second-tier powers in the West as Italy.

Might the same thing be happening to the Chinese Communist government? Their development indeed appears to be fast—but so did Nazi Germany’s. They have been sinking a great deal of money into armaments in order to mount a credible competition with the US. They have evidently been spending a lot of money to subvert prominent people in other parts of the world, and spending hugely on their “belt and road initiative” to buy influence abroad. There have been vast flashy infrastructure projects, high-speed trains and giant dams and the like. Just like Hitler with his Berlin Olympics and celebrated system of autobahns. Is it all an attempt to impress without real substance behind it? There have been entire cities constructed which, rumor has it, have been in the end abandoned and left to rot.

We do not know what is real, because, like Nazi Germany or the Soviets, the accounting for all of this has not been public. But surely, if it were real, there would be no reason not to trumpet the actual figures.

In theory, the Chinese economy should not work. Like that of the old Soviet Union, it lacks incentives. The joke then was “we pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.” While China has to some extent gone “free market” there is still a heavy burden of government, taxation, and systemic favouritism towards government-run businesses, so that hard work and enterprise is not well-rewarded. In theory, central control is also going to be less efficient in allotting funds and resources than are free markets. To put it plainly, Chinese-style central planning has never worked elsewhere. It has only appeared, for limited periods, to work.

We also know that Chinese demographics ought about now to be hitting a wall. China’s rise was based on cheap labour, and, thanks in some part to the “one-child policy,” China is due to be running out of cheap labour. In theory, they might make a successful transition to a consumer-based and high-skills economy; Japan did before them; Korea did before them; Taiwan did before them. But notice that, at the moment they made this transition, Japan, Korea, or Taiwan also shifted from command economies to liberal democracies. Nobody has ever developed to this high-skills, consumerist level before without throwing off autocracy and central planning.

The Chinese Communist Party might have taken this route. They chose against it at Tiananmen, and have not looked back. They have since systematically suppressed civil society, necessary for such a transition: the Christian churches, the mosques, Falun Gong. No autocracy now means no CCP.

We further know that China has taken a big economic hit recently: first because of the trade war with Trump’s US; then thanks to the coronavirus and the shutdown it required; now also because their markets are also in a coronavirus slump; and other nations are either talking about or enacting “decoupling.”

Skim milk masquerades as cream.

Skim milk masquerades as cream.Keep all this in mind, and their lunge to assume full control of Hong Kong might appear to be about more than mere power. Hong Kong has a great deal of real wealth—audited and substantial. Might it be that, just as Hitler decided to confiscate the considerable assets of the Jews, or Philip IV of France decided to cancel his debt to the Templars by declaring the order illegal, the CCP wants or needs to commandeer the assets of Hong Kong and its banks for government purposes to keep things ticking over for a few more years?

It may very well not work, and in the meantime the move has probably hurt China’s trade prospects further. But this may indicate just how desperate the Chinese government is. All they can afford to think of, perhaps, is meeting the next payroll, the next mortgage payment.

They have, at the same time, been putting Uyghurs, Falun Gong, and others in camps, just as Hitler did the Slavs or the Jews. For the Nazis, this was explicitly planned as a money-making proposition: slave labour. Might it be so for the Chinese government too? Along with a cash stream from organs harvested from prisoners for transplants. China has been fingered as the ultimate source of the recent flood of dangerous opioids in North America. Might their motivation be, not just, as commonly assumed, to subvert American society, but to make some fast cash, by whatever means necessary? This, after all, is the motive of the Mexican drug cartels themselves; and of the many individual drug dealers in Canada and the USA. There is more money in selling drugs than in most things.

China has also been accused of counterfeiting US bills, and slipping them into circulation. Isn’t the intent most likely to be the same as for domestic counterfeiters—to literally make some fast cash, rather than the more abstract and unlikely goal of subverting the US financial system?

The Chinese government simply cannot really be the eternal fountain of credit and hard coinage it is imagined to be.

But a shortage of money in government is apparently not the only problem.

Why, at this moment, is China making threats against all their neighbours? Just as they are marching into Hong Kong, they are upping the ante over the South China Sea, a move that alienates and threatens a coalition of nations, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, the US, Japan, and Australia. As if these were not enough enemies to deal with, they also provoke India over their border. And declare their rightful ownership of Vladivostok.

This is, as diplomatic or as military strategy, insane. Suppose even that, like Hitler, the CCP figured they needed to confiscate some more assets to survive. Then you would not provoke a big fish like India. You would pick the runt of the litter, like Poland, and try to isolate them.

But it sounds just like Nicolai Ceausescu, in the days and hours before his regime fell. He wrapped himself in the Romanian flag, and insisted that if his countrymen could not all stand together behind their government, national sovereignty was at risk.

This worked for Ceausescu for years, ever since the Russian tanks rolled into Prague in 1968. But now that the Warsaw Pact had fallen apart, it no longer worked. Without this external threat, his support had disappeared, and all he could do was unsuccessfully flee for his life.

The Chinese Communist Party seem to be making the same calculation. They are in desperate need of external enemies. Financially crippled, the economic reckoning beginning, they are no longer able to provide the steadily improving living standards that had sustained them in power domestically by a kind of social contract. As an alternative, they feel they need to play this dangerous game, to encourage the idea that China is surrounded by threats on all sides. So all good Chinese must put aside their misgivings and support the government.

There is a real danger they may provoke a war in order to make this stick. But they obviously do not want a real war. They seem to have calculated that they would lose any war, even with a minor power like Taiwan or Vietnam. Otherwise, they would do as Hitler did, and try to divide and conquer. Instead, they need and are trying to provoke a Cold War, purely for propaganda purposes.

This in itself looks unsustainable, since it requires increasing military expenditures. It was, many argue, the burden of such an arms race that scuppered the Soviet Union.

It all suggests that the PRC is actually now just trying to survive week by week, month by month, perhaps not even year by year. They alone have seen the real figures, and they believe they have no future.

'Od's Blog: Catholic and Clear Grit comments on the passing parade.

Published on July 18, 2020 13:25