Stephen Roney's Blog, page 175

December 12, 2021

For Advent

\

Pope Francis Downplays Sexual Sin

Lust sleeps with Eros

Lust sleeps with ErosPope Francis has just caused more confusion over the faith. To reporters on a flight to Greece, he explained that sins of the flesh are not the most serious. Pride and wrath are worse.

One can understand where he is coming from: otherwise good people can easily be tempted into sexual sins. We all are.

But then, the same is true of pride, or wrath.

Francis is sometimes justified as a “pastoral” pope rather than a deep thinker, in order to justify his sometimes theologically dubious comments. But it is precisely on the pastoral side that his comments are a problem. The prime responsibility of a shepherd is to guide the sheep, not to let them wander. Directions must be clear.

Strictly speaking, there are only two kinds of sin: mortal and venial. Put as simply as possible, a venial sin is one that does not in principle turn away from God; a mortal sin is one that does. A sexual sin, like any sin, can be either—it is all in the intent and motive, not in the act itself. Accordingly, one cannot say that a sin against the sixth commandment is more or less serious, in itself, than a sin against another.

However, the traditional listing of the three temptations is “the world, the flesh, and the devil.” Our Lady of Fatima revealed to Saint Jacinta in visions of hell that “The sins which cause most souls to go to hell are the sins of the flesh.”

It is hard to reconcile this with what the Pope just said. Who you gonna believe, the Pope or the Virgin Mary?

I side with Jacinta and Mary. It is precisely because sins of the flesh are so tempting to good people that they are dangerous. Among sins, they are a “gateway drug.” This is why lust is one of the “Seven Deadly Sins”: not because they are worse in themselves than other sins, but because they are addictive. They become a settled vice, and a vice causes us to turn away from God altogether.

Francis’s comments are, to put the best possible face on them, unhelpful. Who does he serve here?

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

December 11, 2021

You Will Live Forever. Deal with It.

Friend Xerxes has made a declaration in his most recent column:

“Nor are we, as some like to believe, immortal souls temporarily housed in human bodies.”

He does not explain this claim.

To Christians, the Bible is a final authority. The Bible seems utterly definitive in saying this is exactly what we are.

“And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.”

But the Bible also agrees with all other ancient authorities. The pagan Romans and Greeks also held this to be so—that the soul goes on to an afterlife. The Egyptians, Chinese, and Hindus held it to be so. The native people of North America held it to be so. The aborigines of Australia held it to be so.

An appeal to authority is not definitive. But if you are going against all authority, the onus is on you to make your case. As Chesterton observed, you cannot tear down a fence simply because you do not understand why it is there. Nobody has the right to tear down a fence until they do understand why it is there. If you were to proclaim that there was no such place as Africa, you would need to explain why all the atlases are wrong.

Xerxes perhaps hints at an argument in the parenthetical comment, “as some like to believe.” This suggests that people believe in an immortal soul and an afterlife because they find it comforting. This is a familiar claim from Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins.

But why is it not at least as comforting to suppose that at death, consciousness simply ends? What sounds bad about eternal rest? This is the very goal of Buddhism: nirvana, “extinction.” It is the goal of Advaita Vedanta Hinduism: moksha, “release.”

The afterlife, on the other hand, Christian, pagan, Hindu, or Buddhist, implies judgement and just punishment. This cannot be comforting to those conscious of having done wrong. And, according to Christian teaching, we are all worthy of condemnation; nobody can assume salvation.

Remember Hamlet’s famous soliloquy.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep

No more; and by a sleep, to say we end

The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks

That Flesh is heir to? 'Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep,

To sleep, perchance to Dream; aye, there's the rub,

For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come..

It is he who denies the afterlife who is indulging in wishful thinking—whistling past the proverbial graveyard.

Beyond the voice of universal authority, there is empirical evidence—scientific evidence--here and now of the immortality of the soul.

First, it is all but conclusively proven by some “Near Death Experiences” that consciousness continues after physical death, and in the absence of detectable brain activity. There are also examples of people with virtually no brain tissue who nevertheless are conscious and can function normally—suggesting that consciousness is not dependent on the physical brain. The brain may only be, more or less as Descartes suggested, a conduit between consciousness and the physical world, more or less as the eye or hand is. Second, “ghost stories” are common all over the world: encounters with disembodied souls. Many are purely empirical accounts: people see things, people hear things, people feel things. If we do not accept these claims, or accept the simplest explanation for them, isn’t it often only for the unscientific reason that they do not fit materialist preconceptions? They are common all over the world: encounters with disembodied souls. And note that we do not, on the whole, find ghost stories comforting. Believing in an afterlife is not wish fulfilment. Our most natural reaction is fear.

Hamlet suggests the analogy of sleep and dreams. We know that consciousness persists when the senses shut down in sleep. Why wouldn‘t it persist in physical death, when the senses shut down permanently? We all have the experience of consciousness continuing without our physical senses. By contrast, do any of us have any kind of empirical experience of ceasing to exist?

In our experience, sensed objects die or decay or disappear, but thoughts do not. I see a hummingbird at my feeder. After a few minutes, he is gone. Nevertheless, I am still able to see a hummingbird in my mind. Everything is immortal in memory, in thought form: sensations, thoughts, emotions, urges. We may no longer feel the emotion. We may no longer consent to the idea. Yet we can still summon them to consciousness; we are aware of them.

You might object that memories too fade over time. Perhaps this is what Buddhists are counting on. But is it true? Over time, we may have trouble retrieving a particular memory; but it does seem it is always still there somewhere. The taste of a madeleine, as Proust relates, can bring it all back vividly. A smell, a familiar melody—returning to a place. Wilder Penfield could stimulate vivid memories with electric probes.

So it looks as though all things, once created, continue to exist forever in some metaphysical place, the “storehouse memory,” or “storehouse consciousness,” to use the Buddhist phrase. This is perhaps also where abstract eternal concepts reside: the truths of mathematics or logic, the concept of justice, moral good and evil, beauty, truth, and so forth. Plato’s realm of ideal forms, the Bible’s Kingdom of Heaven.

Berkeley pointed out that this realm is more immediate, clear, and certain than the physical world. The existence of the physical world is a mere hypothesis, and an unnecessary one. As Christians, we hold it to be real, on authority. Most cultures do not.

We are immortal souls, temporarily housed in human bodies. At the end of time, we will again be housed in physical bodies, but perfected ones.

December 10, 2021

Modern Parenting Styles

An example essay in the text from which I am teaching seems to have no concept of teaching values or ethics. It classifies parents as either “lenient” or “disciplinarian.” But the only point it sees for “discipline” is “safety and protection of the children.” No thought that learning discipline prepares a child to deal with adversity, to be independent, to achieve success through deferred gratification, or to restrain their instincts out of respect for the rights of others.

Perhaps worse, the essence of discipline is presented as not being permitted to play outside or make friends outside the family. These are a perfect way to prevent a child from learning ethics, or discipline, or how to deal with adversity. They are examples of treating a child like a possession. They are narcissistic on the part of the parent.

But the “lenient” style of parenting, as given, won’t teach ethics either. It is described as just letting the child do as they like, including howling in a crowded theatre.

Either of these “parenting styles” is child abuse. Yet they are presented as the only alternatives, and neither is condemned.

More evidence that our civilization has lost its bearings. Its bearings are its ethics.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

December 9, 2021

What Dreams May Come

John Singer Sargent

John Singer SargentOne argument against the proposition made here recently that dreams are visions of an eternal world, in which we will live after death, is that most of us have both good and bad dreams. So are we bound for heaven, or hell? Shouldn’t good people have only good dreams, and bad people only nightmares?

But that would not be useful. If one had only good dreams, one might stop making an effort. And one might seek death, life by comparison seeming unbearable.

True, those who commit evil are more likely to have nightmares. MacBeth, having murdered Duncan, speaks of “these terrible dreams that shake us nightly.” Lady MacBeth sleepwalks, acting out her sense of guilt. We treat others well so that we sleep soundly at night.

On the other hand, some good people too seem plagued by nightmares.

The point is presumably to warn us that something is wrong. It may be that we have done evil, and are bound for the pit unless we repent. Or it may be that evil is being done to us, and that we must do something to protect ourselves from it. This, after all, is what bodily pain is for.

To know which requires a careful consideration of the dream.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

December 7, 2021

Butterfly Dreams

In the 4th century B.C., Chuang-tzu asked the question. “Am I a man who dreamt last night of being a butterfly, or am I a butterfly dreaming I am a man?”

Has anyone satisfactorily answered this question?

Descartes asks himself the same question:

“At this moment it does indeed seem to me that it is with eyes awake that I am looking at this paper; that this head which I move is not asleep, that it is deliberately and of set purpose that I extend my hand and perceive it; what happens in sleep does not appear so clear nor so distinct as does all this. But in thinking over this I remind myself that on many occasions I have in sleep been deceived by similar illusions, and in dwelling carefully on this reflection I see so manifestly that there are no certain indications by which we may clearly distinguish wakefulness from sleep that I am lost in astonishment. And my astonishment is such that it is almost capable of persuading me that I now dream.”

We pinch ourselves to see if we are awake. But of course this does not work. It should be entirely possible to pinch ourselves in a dream.

Descartes ultimately resolves the question by proposing that God, being by definition all-good, would not delude us; and so what we perceive as clear and distinct must be the reality. And we perceive daily reality, he says, more clearly and more distinctly than we do our dreams.

But does this work?

To begin with, is it obvious that we experience our daily lives more clearly and distinctly than we do our dreams? Or is this just our perception when we are awake? How clearly do we remember how clear and distinct our dreams were, when we are awake? For that matter, how clearly do we remember how clear and distinct our daily life is when we are dreaming? Aren’t dream worlds perfectly clear and distinct while we dream, and our “real” daily life, if we are aware of it at all, vague and distant?

And even if this is so, even if dreams are less clearly perceived than the turnips we had at lunch, doesn’t Descartes’s own logic argue that the world of dreams is also real? Others can lie to us; we can lie to ourselves, causing delusions. We can misinterpret what we see, and mistake a reflection for an oasis. But dreams come neither of our own free will or from others. Nor do they involve the interpretation of some sense perception, introducing human error. While we might also misperceive this or that in a dream, why would God allow them to systematically deceive us?

By Descartes’s logic, he would not. And I do not think anyone else has ever given a batter response to Chuang-tzu. If we accept the world of our senses as real, as referring to a real place, we apparently must accept that the world we perceive in our dreams is also real, referring to a real place. God would not so deceive us.

Most human cultures, at all times and places, have accordingly assumed so. Dreams are either the language in which God talks to us, or they are a window into a real, objectively existing spiritual realm. Or both.

This explains the fact that the images that appear to us in dreams are not arbitrary, but predictable. Although dragons do not occur in the sensed world, the dragon is familiar to cultures all around the world. So is the phoenix, the unicorn, the sea monster, and so forth. Wherever the Greeks or Romans conquered, they had no trouble identifying the local gods as versions of their own gods. Jung traced the same motifs in the dreams of his Zurich patients and in ancient texts from India and elsewhere. He called these archetypes, but never gave a clear and consistent account of where they came from. The structure of the brain?

Why not see them, with Plato, as ideal forms, eternally existent in the spiritual realm?

When Jesus said “the Kingdom of Heaven is within you,” or “among you,” was he referring to its imaginative perception in dreams? Are we given a foretaste of the afterlife, both heaven and hell, in our dreams? Is this where we will live after the physical world fades away, just as it is where we live every night, when we lose consciousness of the physical world around us?

I think it is the obvious assumption.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

December 5, 2021

The Way We Weren't

Marguerite de Bourgeouys sculpture, downtown Montreal

Marguerite de Bourgeouys sculpture, downtown MontrealI am currently forced to homeschool my daughter. It is just as well. We’ve been going through the prescribed text for Canadian history together. It’s alarmingly bad.

Most recently, it includes a chapter of detail about everyday life in New France. This is, to begin with, not a proper subject for history. We have apparently forgotten why we study history in the first place: to learn the lessons of the past. People’s everyday lives do not, on the whole, provide such lessons, for they had little chance to make choices that might alter the course of history. History properly has to do with matters of government policy, for the most part. Life lessons are important too, no doubt, but these we get from tales of saints and heroes and villains; not the lives of average persons in aggregate.

As to government policy, the book asserts, several times, that the French government saw their North American colony as something to exploit “to make the home country rich.” They did this through the mercantile system, forcing the colony to trade with the motherland. This seems a distortion of history. It should go without saying that a colony needed to pay for itself—that the cost of defending and administering it must not be higher than it returned in taxes. But there is every evidence that the French government saw themselves as also being in North America for the benefit of the natives: in order to convert them to Catholic Christianity and teach them how to improve their lives. And the mercantile system equally committed the mother country to trade with the colonies; trade is not exploitation.

As to the lives of ordinary people, the book goes on at some length over just how exploitative the seigneurial system was, whether there was class mobility, and how large was the pre-conquest middle class. Such class analysis tends to presuppose Marxism; otherwise it is of little interest. In any case, the written records are not sufficient to draw any conclusions. It is all conjecture tainted by political agendas. And such an excursus kills any narrative flow; it is the narrative flow that makes history interesting.

The text also diverts from any narrative continuity to point out that torture was used in the Quebec courts—30 times over a century. It goes into the methods in some detail. This may entertain adolescent boys, but it is not relevant to history. It seems little more than an opportunity to gossip unfavourably about our ancestors.

As is the two pages spent on slavery in New France. This seems disproportionate for a practice that was more common almost everywhere else except continental Europe, and which had no economic impact in New France. It seems mostly, again, a chance to find fault with our ancestors.

The book is openly hostile to Catholicism. It suggests that the average habitant was really more pagan than Christian, because “Canadian children heard tales of flying canoes, werewolves, and encounters with the devil.” Even though the same could be said of Canadian children today, or children at any time or place.

Most disturbing to me is that the book spends only a half a page on women in New France, under the segregated subhead “Women in the Workplace.” It is not just that this ignores the work of women in the home, despite the concentration on ordinary people and ordinary lives. It also omits much of the history I read and heard as a student in Quebec half a century ago. Then, we knew of Madeleine de Vercheres, who defended almost single-handed against an Iroquois attack; of Marie de l’Incarnation, who founded the first school on the continent; Margeurite de Bourgeouys, who co-founded Montreal, built the first church, and started the first school; Jeanne Mance, who started the first hospital, which grew to a string of hospitals across Eastern Canada; Marie-Marguerite d'Youville, who built the first orphanage and hospice, the origins of the Canadian social security system; and St. Kateri Tekakwitha.

Now all we get is brief sentences about some woman running a mill, or continuing their husband’s business after his death.

Why this radical devaluation of women? In part, I imagine, because it is now politically incorrect to say anything that sounds good about Catholics or the religious; and most of these women were nuns. In part, I imagine, because it is politically incorrect to admit that women had important roles before Betty Friedan. They were supposed, after all, to be oppressed.

It would all have been a terrible miseducation for my daughter.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

December 4, 2021

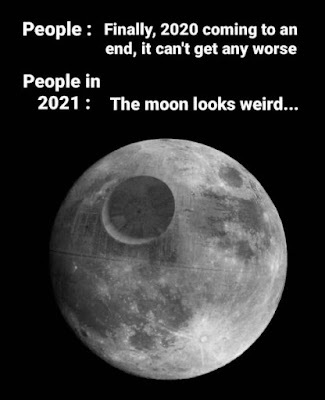

A Few Reasons for Hope

Back in early 2020 we joked about how 2020 was one piece of incredibly bad news after another. And we looked forward to 2021 taking over. But 2021 has probably been worse than 2020—notably in number of covid deaths. And the bad news keeps coming.

Here are a few hopeful thoughts:

Crisis tends to precipitate change.

1. In France, a presidential election cycle is beginning. Macron, the incumbent, is a centrist. His two closest rivals are both on the right. And not the centre right, not Gaullists; on the “far right,” people The Economist used to refer to as “thugs.” The “far right” candidates may not win, but the discussion and the issues have changed. The argument always used to be between the Gaullists and the Socialists. The Socialists are pretty much out of the picture.

2. In Britain, we have seen Brexit and the historic defeat of a left-leaning Labour Party in the last general election. Even if Boris Johnson is squishy, he faces competition from the right, from Nigel Farage and UKIP, as well as from the left. If those right of him do not have a presence in parliament, Farage demonstrated in the last European election that this could soon change, if they grow dissatisfied.

3. In the USA, the Democrats narrowly won the last election cycle; but the polls show their popularity now extremely low. It is not just Joe Biden who looks as though he could not get re-elected. Kamala Harris is almost as unpopular. The current cold shower of leftist policies may inoculate the States from voting left for some time to come. Just as it was unlucky for the Republicans to be in power when the Great Depression hit, or in the 2008 financial crisis. Trump himself should have been reelected, had it not been for Covid. Now the Democrats probably own it, and more.

4. The shakiness of the Chinese economy may be bad news for the world’s markets, and may cause recession or depression. That’s the bad news. But it may also cause the regime to fall. That would be much more significant good news. China under the current regime is the main threat to freedom and to world peace. It is more than a little perverse to worry about a bad Chinese economy.

5. There is a chance that the new Omicron variant of covid is milder—we do not know yet. If it is milder, it may be to our benefit that it out-competes more dangerous strains. If it is not milder, the next strain may be. We may settle down to a covid that is no more dangerous than the seasonal flu.

6. The left is fighting back harder and harder, and making more and more outlandish claims and demands. They are more obviously simply denying truths we can all see for ourselves. This feels like the final act. “First they ignore you. Then they mock you. Then they fight you. Then you win.” The left is spending quickly any moral capital they once claimed. As it gets harder for good people and for intelligent people to be on the left, people may soon be ashamed to admit they are on the left, for fear of scorn or ridicule. When this happens, and it feels close, it is over.

7. The left is now in a position, thanks to political correctness and open denial of realities, of finding humour hostile. As a result, Saturday Night Live is no longer funny; Gutfield is. Stephen Colbert is no longer funny. Steven Crowder is. Nobody hears from The Onion any longer. It is now always the Babylon Bee. When it is no longer fun to be on one side, the other side wins. We saw this in the Sixties when the funny stuff was all on the left: National Lampoon, Month Python, George Carlin, Lenny Bruce. It was the best evidence that the right was intellectually bankrupt then. Now it shows the positions have flipped.

8. More and more public personalities who used to be on the left, or whom we assumed to be on the left, are now moving to or coming out as rightist. Dr. Oz is one recent example. When he announced for the Senate, I automatically assumed it was for the Democrats. He was Hollywood, and he was Oprah. Not so. He was a closet Republican. Tim Poole has stopped insisting he is on the left. Joe Rogan sounds more right wing. Jon Stewart sounds more right-wing. Jimmy Dore sounds more right-wing. People are walking away. I suspect that soon it will not be cool to be on the left.

9. It looks as though the Supreme Court might, by summer, overturn or restrict Roe v. Wade. While this would make no immediate difference even in the USA, it would be a heavy blow to the argument that abortion is a human right, accepted in Canada and perhaps elsewhere largely on the American model.

10. In the end, you cannot hold back the avalanche of information on the Internet.

Hope this helps.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

December 3, 2021

Happily Ever After?

Do you recognize the person in this picture?

Do you recognize the person in this picture?Nobody seems to get fairy tales.

A text from which I am currently teaching uses Cinderella as a hook. “Almost everyone knows how the story of Cinderella ends, but do people actually think about how she spent her days before she met the prince?”

Suprisingly, at least to me, few students seem to find the answer obvious. Even though without it, without Cinderella’s initial state of neglect and abuse, there is no story. Even though it is made her and the story’s defining characteristic: “Ella-in-the-cinders.” Everyone seems to think of her only as the happily-ever-after princess, in a princess gown.

But my text itself seems not to get it. It goes on to comment, “If someone had asked Cinderella what chores she did not particularly like, she probably would have answered, ‘Why none, of course. Housework is my duty.’” As though she was perfectly content with sleeping in the cinders while her sisters went to the ball.

Why this weird blindness to what is, primarily, a tale of child abuse?

So, indeed, are most fairy tales. Snow White’s mother wants to kill her and eat her. Beauty’s father allows her to do all the work, while her two sisters abuse her relentlessly. Then he expects her to give up her life for his. Hansel and Gretel’s parents abandon them twice to be eaten by wolves. Rapunzel’s parents trade her for a mess of potage, then her stepmother locks her in an exitless tower.

Yet nobody seems to notice. Over time, most fairy tales have been sanitized, supposedly to remove anything that would upset small children. The violence is taken out, and any sexual innuendo. Witches or trolls may be too scary. Yet the abuse tends to remain, as though no one notices it—although, to be fair, it is so central to the stories that they would probably be meaningless without it.

It is not just child abuse which seems to be invisible in storyland. Jesus’s parables, too, are invariably misinterpreted. For example, nobody seems to notice the critical point of “The Good Samaritan”—although it is also apparent in its common title. It is not just the obvious point that it is good to do good; it is that the one person who did good was a Samaritan. After thieves had done evil, and a priest and a Levite ignored it.

The parable of the Prodigal Son I have seen similarly misinterpreted, even though the point is again in the standard title. Some apparently think that it is all about condemning the one son for wanting to leave the family farm.

In the Parable of the Talents, nobody seems to notice that the servant who is praised for good stewardship has made the money by lending at interest—prohibited by the Mosaic Law.

Although not a parable, the story of the woman taken in adultery is a similar case. Everybody seems to insist that Jesus overlooks the sin of the woman caught in adultery. He does not; he calls her out for it, and tells her to go and sin no more. The point is that he is not prepared to stone her to death, to give up on her.

My friend Xerxes, quoting some Protestant theologian, recently asserted that Jesus’s parables on the Kingdom of Heaven were really about the value of friendship. Heaven was being a friend to all. None of this nonsense about sheep and goats.

It occurs to me that there is a common thread here. It is a general denial of evil. We refuse to see evils committed in front of us; we pretend they do not exist.

To do so, to wash our hands and ask, with Pilate, “what is truth?” is itself the ultimate evil. Anyone might do an evil act. But to categorically deny the existence of evil is to crucify Christ in the flesh.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.

So You Thought It Was Over?

[image error] Is there really a bat in here?

Two bits of troubling information on Covid. First, confirmation that people who have previously had Covid can be reinfected with the Omicron variant. Second, 80% of a sampling of white-tail deer have or have had Covid. So Covid now has an “animal reservoir” from which to re-emerge forever in new variants, even if we eliminate it in the human population.

Pandora’s box is well and fully open now.

But as with Pandora’s box, one hope remains: that Omicron will be milder in its effects.

'Od's Blog: Catholic comments on the passing parade.