Lawrence Block's Blog, page 24

April 7, 2012

Your chance to own a piece of Bernie

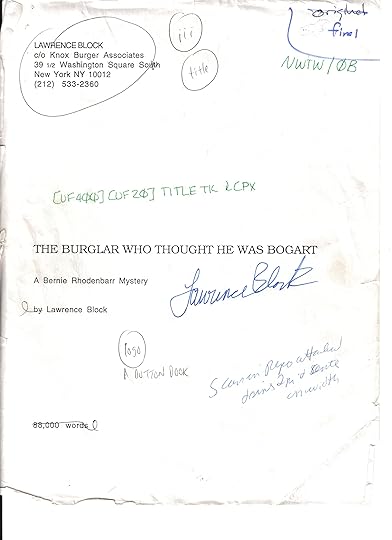

In 1977, Bernie Rhodenbarr made his debut in Burglar's Can't Be Choosers. In 1995, he had his seventh appearance in The Burglar Who Thought He Was Bogart. And eight years later, in late 2003, a woman in O'Fallon, Illinois, bought the original manuscript of Bogart.

In 1977, Bernie Rhodenbarr made his debut in Burglar's Can't Be Choosers. In 1995, he had his seventh appearance in The Burglar Who Thought He Was Bogart. And eight years later, in late 2003, a woman in O'Fallon, Illinois, bought the original manuscript of Bogart.Last fall, I'm sorry to report, she passed away. And last week her daughter got in touch, and we arranged that I'd find a new owner for the manuscript. I've just posted it on eBay, with a minimum opening bid of 99¢.

If you're a collector, well, note that this is a unique item, the copy-edited manuscript that went to the printer and was returned to me after publication. It's signed on the title page, and there are pencil corrections throughout. I've been assured that I could best monetize the item by donating it (or even selling it) to a university library, but I'd much rather it go to someone who wants to own it rather than disappear into an institution's archives.

If you're a collector, well, note that this is a unique item, the copy-edited manuscript that went to the printer and was returned to me after publication. It's signed on the title page, and there are pencil corrections throughout. I've been assured that I could best monetize the item by donating it (or even selling it) to a university library, but I'd much rather it go to someone who wants to own it rather than disappear into an institution's archives.There's no reserve on this. The high bidder gets it, period. But I have a feeling it's going to run you more than 99¢...

Here the link.

Published on April 07, 2012 11:50

April 5, 2012

Getting By on a Writer's Income

Recently, to give you all a taste of one of the new books for writers I ePublished in 2011, I posted a Writer's Digest column of mine ("Writing, Always Writing") from The Liar's Companion. Enough of you responded enthusiastically to prompt me to Do It Again.

So here's a piece that originally appeared in 1981 in an annual publication, Writer's Yearbook. Dated references notwithstanding, I'd have to say it's held up well. The points it makes seem as valid as ever, and the concerns it addresses have certainly not gone away.

I was grateful for the opportunity to include it in The Liar's Bible, and I'm happy to share it here...

GETTING BY ON A WRITER'S INCOME

A writer, James Michener has said, can make a fortune in America. But he can’t make a living.

I think the point is good. It’s hardly a secret that a few people get rich every year at their typewriters. The same media attention that 50 years ago lionized a handful of writers as important cultural leaders now trumpets the income of a comparable handful. The tabloid reader knows nowadays about paperback auctions and movie tie-ins and multi-volume book contracts with sky-high advances and elevator clauses.

Balanced against this image of the writer as fortune’s darling is a similarly glamorous picture of the unsuccessful writer starving in an airless garret, eating baked beans out of the can and pawning his overcoat to buy carbon paper. The poor blighter’s starving for his art, and he’ll either go on starving in pursuit of his pure artistic vision until they lay his bones in potter’s field, or else he’ll suddenly break through to literary superstardom, and the next we’ll see of him he’ll be at poolside sipping champagne and snorting lines with the Beautiful People.

The validity of both of these images notwithstanding, most of the writers I know have never gotten rich but have always gotten by. This has certainly been the case with me. I have, to be sure, had good years and bad years. I had a couple of years when I made more money than I knew what to do with—although I always thought of something—and I had other years, and rather more of them, when I might have switched to another line of work had there been anything else for which I was qualified.

I did live in a garret once, in a rather pleasant area under a sloping roof atop a barbershop in Hyannis, Massachusetts. For a couple of weeks I subsisted solely on peanut butter sandwiches and Maine sardines, and I wrote a short story every day, one of which ultimately became my first sale. (The room was $8 a week, the sardines were 15¢ a can, and I got a hundred bucks for the story...)

Click here to read the rest...

So here's a piece that originally appeared in 1981 in an annual publication, Writer's Yearbook. Dated references notwithstanding, I'd have to say it's held up well. The points it makes seem as valid as ever, and the concerns it addresses have certainly not gone away.

I was grateful for the opportunity to include it in The Liar's Bible, and I'm happy to share it here...

GETTING BY ON A WRITER'S INCOME

A writer, James Michener has said, can make a fortune in America. But he can’t make a living.

I think the point is good. It’s hardly a secret that a few people get rich every year at their typewriters. The same media attention that 50 years ago lionized a handful of writers as important cultural leaders now trumpets the income of a comparable handful. The tabloid reader knows nowadays about paperback auctions and movie tie-ins and multi-volume book contracts with sky-high advances and elevator clauses.

Balanced against this image of the writer as fortune’s darling is a similarly glamorous picture of the unsuccessful writer starving in an airless garret, eating baked beans out of the can and pawning his overcoat to buy carbon paper. The poor blighter’s starving for his art, and he’ll either go on starving in pursuit of his pure artistic vision until they lay his bones in potter’s field, or else he’ll suddenly break through to literary superstardom, and the next we’ll see of him he’ll be at poolside sipping champagne and snorting lines with the Beautiful People.

The validity of both of these images notwithstanding, most of the writers I know have never gotten rich but have always gotten by. This has certainly been the case with me. I have, to be sure, had good years and bad years. I had a couple of years when I made more money than I knew what to do with—although I always thought of something—and I had other years, and rather more of them, when I might have switched to another line of work had there been anything else for which I was qualified.

I did live in a garret once, in a rather pleasant area under a sloping roof atop a barbershop in Hyannis, Massachusetts. For a couple of weeks I subsisted solely on peanut butter sandwiches and Maine sardines, and I wrote a short story every day, one of which ultimately became my first sale. (The room was $8 a week, the sardines were 15¢ a can, and I got a hundred bucks for the story...)

Click here to read the rest...

Published on April 05, 2012 18:05

March 31, 2012

If you'd like to vote for Matthew Scudder...

...now's your chance. A Drop of the Hard Stuff has been shortlisted for a Spinetingler award, and the polls are open right now. It's pretty simple, you just click here, scroll down through the categories, and vote as the spirit moves you. Scudder's in the "Legend" category, limited to authors of nine or more books. You can vote for him, or you can vote for one of his competitors. Wisconsin residents would probably welcome the opportunity to vote for Fighting Bob La Follette, but there doesn't seem to be a write-in option.

The Scudder novels have probably had more than their fair share of awards over the years, but one for A Drop of the Hard Stuff would certainly be welcome, as the book continues to sell well. It's newly available in trade paperback, the eBook edition has been reduced in price to a much more palatable $9.99, and the Mulholland Books hardcover is still a strong seller almost a year after its original publication. Amazon and Barnes & Noble have discounted the hardcover to $14.12, which is less than the list price of the paperback, so if you've somehow managed to resist owning a copy, well, maybe it's time to surrender to the inevitable...

The Scudder novels have probably had more than their fair share of awards over the years, but one for A Drop of the Hard Stuff would certainly be welcome, as the book continues to sell well. It's newly available in trade paperback, the eBook edition has been reduced in price to a much more palatable $9.99, and the Mulholland Books hardcover is still a strong seller almost a year after its original publication. Amazon and Barnes & Noble have discounted the hardcover to $14.12, which is less than the list price of the paperback, so if you've somehow managed to resist owning a copy, well, maybe it's time to surrender to the inevitable...

Click here to read the rest of this post...

The Scudder novels have probably had more than their fair share of awards over the years, but one for A Drop of the Hard Stuff would certainly be welcome, as the book continues to sell well. It's newly available in trade paperback, the eBook edition has been reduced in price to a much more palatable $9.99, and the Mulholland Books hardcover is still a strong seller almost a year after its original publication. Amazon and Barnes & Noble have discounted the hardcover to $14.12, which is less than the list price of the paperback, so if you've somehow managed to resist owning a copy, well, maybe it's time to surrender to the inevitable...

The Scudder novels have probably had more than their fair share of awards over the years, but one for A Drop of the Hard Stuff would certainly be welcome, as the book continues to sell well. It's newly available in trade paperback, the eBook edition has been reduced in price to a much more palatable $9.99, and the Mulholland Books hardcover is still a strong seller almost a year after its original publication. Amazon and Barnes & Noble have discounted the hardcover to $14.12, which is less than the list price of the paperback, so if you've somehow managed to resist owning a copy, well, maybe it's time to surrender to the inevitable...Click here to read the rest of this post...

Published on March 31, 2012 08:14

March 28, 2012

Speaking tonight, free admission!

Quick eleventh-hour reminder: I'll be talking at the Salmagundi Club, a very pleasant venue at 47 Fifth Avenue, at 6:30 this evening. Free admission. If you're in town and couldn't get tickets for Book of Mormon, come by and say hello. Details here: http://lawrenceblock.wordpress.com/lb...

Published on March 28, 2012 08:31

March 26, 2012

Writing, always writing...

In 1976 I began a monthly instructional column on fiction writing for Writers Digest, and kept at it for fourteen years. Two books, Telling Lies for Fun & Profit and Spider, Spin Me a Web, grew out of that job, and they're both still in print many years and editions later.

But it wasn't until last year that I gathered up my later WD columns and made two Open Road eBooks out of them. Having noted that Telling Lies consistently outsold Spider by a factor of four or five to one, I called the new books The Liar's Bible and The Liar's Companion. They've had a good reception, and Open Road has since made them available as trade paperbacks.

But it wasn't until last year that I gathered up my later WD columns and made two Open Road eBooks out of them. Having noted that Telling Lies consistently outsold Spider by a factor of four or five to one, I called the new books The Liar's Bible and The Liar's Companion. They've had a good reception, and Open Road has since made them available as trade paperbacks.

Still, it's clear that many fans of Telling Lies are largely unaware of the two new books. I can tell you that if you like Telling Lies you're apt to find Bible and Companion at least as valuable, that they're very much of a piece with the earlier work, that the only real difference is that they were written by a fellow who'd lived a few more years, written a few more books, and possibly learned a thing or two in the process.

I wonder, though. Instead of trying to draw you a picture, suppose I give you a couple thousand words?

So here's a sample column, one of the first chapters in The Liar's Companion. It appeared in the magazine in 1987. If you like it, well, I'll probably post additional chapters here from time to time. Or I suppose you could always cut to the chase and buy the book...

So here's a sample column, one of the first chapters in The Liar's Companion. It appeared in the magazine in 1987. If you like it, well, I'll probably post additional chapters here from time to time. Or I suppose you could always cut to the chase and buy the book...

WRITING, ALWAYS WRITING

Man must work from sun to sun.

Woman’s work is never done.

That, at least, is how they put it in the bad old days of sexism and long hours. Now, what with union contracts and feminism, not to mention the around-the-clock shifts facilitated by electrification, the old rhyme simply won’t stand up. How can we update it, to produce a suitable bromide for our times?

Mere mortals work from 9 to 5.

A writer works when he’s alive.

Well, it rhymes and it scans, but I can’t say I’m crazy about it. There ought to be a better way to convey in verse the idea that the writer’s work never ceases. Perhaps we’ll take another stab at it in a little while. Meanwhile, let’s examine not the rhyme but the reason...

Click here to read the rest of the post...

But it wasn't until last year that I gathered up my later WD columns and made two Open Road eBooks out of them. Having noted that Telling Lies consistently outsold Spider by a factor of four or five to one, I called the new books The Liar's Bible and The Liar's Companion. They've had a good reception, and Open Road has since made them available as trade paperbacks.

But it wasn't until last year that I gathered up my later WD columns and made two Open Road eBooks out of them. Having noted that Telling Lies consistently outsold Spider by a factor of four or five to one, I called the new books The Liar's Bible and The Liar's Companion. They've had a good reception, and Open Road has since made them available as trade paperbacks.Still, it's clear that many fans of Telling Lies are largely unaware of the two new books. I can tell you that if you like Telling Lies you're apt to find Bible and Companion at least as valuable, that they're very much of a piece with the earlier work, that the only real difference is that they were written by a fellow who'd lived a few more years, written a few more books, and possibly learned a thing or two in the process.

I wonder, though. Instead of trying to draw you a picture, suppose I give you a couple thousand words?

So here's a sample column, one of the first chapters in The Liar's Companion. It appeared in the magazine in 1987. If you like it, well, I'll probably post additional chapters here from time to time. Or I suppose you could always cut to the chase and buy the book...

So here's a sample column, one of the first chapters in The Liar's Companion. It appeared in the magazine in 1987. If you like it, well, I'll probably post additional chapters here from time to time. Or I suppose you could always cut to the chase and buy the book...WRITING, ALWAYS WRITING

Man must work from sun to sun.

Woman’s work is never done.

That, at least, is how they put it in the bad old days of sexism and long hours. Now, what with union contracts and feminism, not to mention the around-the-clock shifts facilitated by electrification, the old rhyme simply won’t stand up. How can we update it, to produce a suitable bromide for our times?

Mere mortals work from 9 to 5.

A writer works when he’s alive.

Well, it rhymes and it scans, but I can’t say I’m crazy about it. There ought to be a better way to convey in verse the idea that the writer’s work never ceases. Perhaps we’ll take another stab at it in a little while. Meanwhile, let’s examine not the rhyme but the reason...

Click here to read the rest of the post...

Published on March 26, 2012 20:39

March 24, 2012

No, I won't give you a blurb. Here's why:

Sometime next month I'll sit down with

The Cocktail Waitress,

an unpublished novel by James M. Cain. Hard Case Crime's Charles Ardai, who's published many worthy novels (not a few of them mine), unearthed Cain's manuscript, edited it with his characteristic sensitivity, and will publish it this fall.

I expect to enjoy it. But, like it or not, I'm sure I'll give it a blurb.

It's been around fifteen years—maybe closer to twenty—since I stopped giving blurbs. I made the decision for a couple of reasons. First, I was getting more manuscripts and galleys than I could possibly have read, even if I did nothing else, even if I were a certified graduate of Evelyn Wood's speed-reading school. Giving blurbs, after all, is like feeding pigeons, and every time you say something nice about somebody's book, five more editors add you to their list of prospects, and ten more ARCs turn up in the mail.

Nor did I want to be stuck with the choice of saying something nice about a book I didn't care for or indicating my dislike of the thing to its editor or author. The only way to avoid that particular no-win situation is to steer clear of the whole business. Hence, no blurbs.

This is a stance many writers adopt sooner or later. A rush of blurbish generosity is a not uncommon response to success, and both Stephen King and Mario Puzo were at one point accused of never having met a book they didn't like. I never knew Mr. Puzo, so can't guess what he did or didn't read and did or didn't like, but I've had enough contact with Steve King to doubt he ever blurbed a book he didn't care for. He takes his responsibilities too seriously for that. But he's always been an avid reader, and his enthusiasms are considerable...

Click here to read the rest

I expect to enjoy it. But, like it or not, I'm sure I'll give it a blurb.

It's been around fifteen years—maybe closer to twenty—since I stopped giving blurbs. I made the decision for a couple of reasons. First, I was getting more manuscripts and galleys than I could possibly have read, even if I did nothing else, even if I were a certified graduate of Evelyn Wood's speed-reading school. Giving blurbs, after all, is like feeding pigeons, and every time you say something nice about somebody's book, five more editors add you to their list of prospects, and ten more ARCs turn up in the mail.

Nor did I want to be stuck with the choice of saying something nice about a book I didn't care for or indicating my dislike of the thing to its editor or author. The only way to avoid that particular no-win situation is to steer clear of the whole business. Hence, no blurbs.

This is a stance many writers adopt sooner or later. A rush of blurbish generosity is a not uncommon response to success, and both Stephen King and Mario Puzo were at one point accused of never having met a book they didn't like. I never knew Mr. Puzo, so can't guess what he did or didn't read and did or didn't like, but I've had enough contact with Steve King to doubt he ever blurbed a book he didn't care for. He takes his responsibilities too seriously for that. But he's always been an avid reader, and his enthusiasms are considerable...

Click here to read the rest

Published on March 24, 2012 18:44

March 20, 2012

We pretend to write. . .

At the invitation of the indispensable John Kenyon, I wrote a piece on narrative experimentation for Grift Magazine, the landmark first issue of which has just appeared. Here's a taste of my contribution:

Sometime in the late 1960s I began to feel uneasy about the whole notion of the novel. I’d been writing them for a decade or so, and my rate of production was such that I must have produced well over 100 of the little rascals. The sheer force of numbers may have had something to do with my discontent, which manifested in a sense that the novel was essentially artificial.

I mean, here’s this voice, in the first or third person, and it’s nattering away at you, and why should you believe it, or pay it any attention? Here’s this book with Edgar Allan Pomander’s name on the cover, and it’s being narrated by a character named Henry David Thornton, and where’d he come from?

It was, to be sure, deceitful. H. D. Thornton was but a figment of E. A. Pomander’s imagination, and the story he passed off as his own was sheer fabrication on Pomander’s part. But let us be clear: it wasn’t the deceit that bothered me, or the artifice.

What troubled me was that it was insufficiently deceptive. In the last days of the Soviet Union, a laborer summed up the way the system functioned: “We pretend to work,” he said, “and they pretend to pay us.” Well, our characters pretended to tell their stories, and our readers pretended to believe them. This voluntary suspension of disbelief is of course the compact between reader and writer upon which all fiction depends, and I was fine with that. But while we were pretending, why not pretend that the book was something more than a novel? Why not let it pretend to be an actual document?

That’s how the novel began. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, generally considered to be the first English novel, recounts the titular heroine’s story in the form of letters to her sister, and Richardson’s later novels were similarly epistolary in structure. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is a novel in the form of a journal, while A Journal of the Plague Year, which reads like a contemporary journal, is actually a complex historical novel.

But I didn’t go back that far for inspiration. While I was chafing at the whole notion of the novel, I read a couple of books that made me interested in the notion of novel-as-fictional-document. One, Mark Harris’s Wake Up, Stupid!, was epistolary, but in a very different fashion from Pamela, consisting as it did of the letters to and from the protagonist. It was also hysterically funny, with one elaborately set up gag hinging on the missing letter on one character’s typewriter, all resolved in an epistle in which he recounts a tearful meeting with a lover: “And all night long we cried and cried and cried and ucked and ucked and ucked.”

Click here to read the rest of the post...

Sometime in the late 1960s I began to feel uneasy about the whole notion of the novel. I’d been writing them for a decade or so, and my rate of production was such that I must have produced well over 100 of the little rascals. The sheer force of numbers may have had something to do with my discontent, which manifested in a sense that the novel was essentially artificial.

I mean, here’s this voice, in the first or third person, and it’s nattering away at you, and why should you believe it, or pay it any attention? Here’s this book with Edgar Allan Pomander’s name on the cover, and it’s being narrated by a character named Henry David Thornton, and where’d he come from?

It was, to be sure, deceitful. H. D. Thornton was but a figment of E. A. Pomander’s imagination, and the story he passed off as his own was sheer fabrication on Pomander’s part. But let us be clear: it wasn’t the deceit that bothered me, or the artifice.

What troubled me was that it was insufficiently deceptive. In the last days of the Soviet Union, a laborer summed up the way the system functioned: “We pretend to work,” he said, “and they pretend to pay us.” Well, our characters pretended to tell their stories, and our readers pretended to believe them. This voluntary suspension of disbelief is of course the compact between reader and writer upon which all fiction depends, and I was fine with that. But while we were pretending, why not pretend that the book was something more than a novel? Why not let it pretend to be an actual document?

That’s how the novel began. Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, generally considered to be the first English novel, recounts the titular heroine’s story in the form of letters to her sister, and Richardson’s later novels were similarly epistolary in structure. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is a novel in the form of a journal, while A Journal of the Plague Year, which reads like a contemporary journal, is actually a complex historical novel.

But I didn’t go back that far for inspiration. While I was chafing at the whole notion of the novel, I read a couple of books that made me interested in the notion of novel-as-fictional-document. One, Mark Harris’s Wake Up, Stupid!, was epistolary, but in a very different fashion from Pamela, consisting as it did of the letters to and from the protagonist. It was also hysterically funny, with one elaborately set up gag hinging on the missing letter on one character’s typewriter, all resolved in an epistle in which he recounts a tearful meeting with a lover: “And all night long we cried and cried and cried and ucked and ucked and ucked.”

Click here to read the rest of the post...

Published on March 20, 2012 12:04

March 13, 2012

The Shifting Sands of Time

Not long ago I reacquired the print and electronic rights to three Matthew Scudder novels that had gone out of print. With the capable assistance of my friends at Telemachus Press, I've brought them out as eBooks, and over the past several weeks they've received a heartening reception on Amazon, Kindle and Smashwords. (Apple takes a little longer, but in a week or so you'll find them there as well.)

And, in a matter of weeks, they'll also be available as handsome trade paperbacks, similar in format to The Night and the Music. But this is not the time to ballyhoo those editions. I'll do so relentlessly when the time comes, but now I want tell you instead about the persistent endurance of a noisome textual error.

I spent all of today proofreading the PDF file of A Stab in the Dark, the fourth Scudder novel, the book that introduces Jan Keane, the book where Scudder is first faced with the notion that his drinking just might be problematic. Arbor House published it in 1981, and it has been reprinted in a slew of paperback editions by a batch of publishers.

Today was my third reading of the book in the past couple of months. I wrote it long before I had a computer, but it wasn't necessary to have an OCR scan of the text, as I managed to obtain a digital file. That file, however, was of the UK version, with bits of dialogue surrounded by ' and ' rather than " and ". This can be changed by means of a global-search-and-replace, but what you wind up with requires a good going-over, as there's a lot that can go wrong. (You ain"t seen nothin" yet, folks.)

Click here to read the rest...

And, in a matter of weeks, they'll also be available as handsome trade paperbacks, similar in format to The Night and the Music. But this is not the time to ballyhoo those editions. I'll do so relentlessly when the time comes, but now I want tell you instead about the persistent endurance of a noisome textual error.

I spent all of today proofreading the PDF file of A Stab in the Dark, the fourth Scudder novel, the book that introduces Jan Keane, the book where Scudder is first faced with the notion that his drinking just might be problematic. Arbor House published it in 1981, and it has been reprinted in a slew of paperback editions by a batch of publishers.

Today was my third reading of the book in the past couple of months. I wrote it long before I had a computer, but it wasn't necessary to have an OCR scan of the text, as I managed to obtain a digital file. That file, however, was of the UK version, with bits of dialogue surrounded by ' and ' rather than " and ". This can be changed by means of a global-search-and-replace, but what you wind up with requires a good going-over, as there's a lot that can go wrong. (You ain"t seen nothin" yet, folks.)

Click here to read the rest...

Published on March 13, 2012 18:53

March 9, 2012

The Dachshund in the Fenster

It's been a while since I've posted, but not for lack of interest in communicating with y'all. My cherished companion and I have just returned from a small-ship cruise of the Indian Ocean, from Mauritius to Zanzibar, tarrying along the way in Reunion, Madagascar, Mayotte and the Comoros. It was a part of the world I'd long wanted to see, and it didn't disappoint.

I'm occasionally asked if my relentless globetrotting is in aid of my work. Since most of my books are set in New York, the answer would seem to be self-evident. While I did set Tanner on Ice in Burma, not long after our return from that country, I can assure you I didn't have that in mind while we were over there. (I never figured I'd write anything more about Tanner, let alone send him off to Burma. Go know.)

My travel is for pleasure. No doubt it's for other things as well—a shift of perspective, a break from routine, the alluring illusion of enlightenment—but it's emphatically not for research. Why would I want to ruin a pleasant experience by writing about it?

Yet I will write about the cruise, and soon. For the past two and a half years I've been contributing a monthly column to Linn's Stamp News, and I suspect my next column will concern the philatelic history of several of the places we visited. It seems appropriate; these are countries I've long known only through the medium of stamp collecting, and it's interesting to me the way travel and philately tend to inform each other. Considering that three of our ports of call in Madagascar—Ile Ste. Marie, Diego Suarez, and Nossi-Be—were all individual stamp-issuing entities for a time in the 19th Century, I don't think I'll have much trouble filling a column...

Click here to read the rest.

I'm occasionally asked if my relentless globetrotting is in aid of my work. Since most of my books are set in New York, the answer would seem to be self-evident. While I did set Tanner on Ice in Burma, not long after our return from that country, I can assure you I didn't have that in mind while we were over there. (I never figured I'd write anything more about Tanner, let alone send him off to Burma. Go know.)

My travel is for pleasure. No doubt it's for other things as well—a shift of perspective, a break from routine, the alluring illusion of enlightenment—but it's emphatically not for research. Why would I want to ruin a pleasant experience by writing about it?

Yet I will write about the cruise, and soon. For the past two and a half years I've been contributing a monthly column to Linn's Stamp News, and I suspect my next column will concern the philatelic history of several of the places we visited. It seems appropriate; these are countries I've long known only through the medium of stamp collecting, and it's interesting to me the way travel and philately tend to inform each other. Considering that three of our ports of call in Madagascar—Ile Ste. Marie, Diego Suarez, and Nossi-Be—were all individual stamp-issuing entities for a time in the 19th Century, I don't think I'll have much trouble filling a column...

Click here to read the rest.

Published on March 09, 2012 16:46

February 16, 2012

Matthew Scudder's eVailable!

It's been some time now since three of the Matthew Scudder titles went out of print. I got the rights back, and am very happy to announce that A Stab in the Dark, A Walk Among the Tombstones, and A Long Line of Dead Men are now eVailable, expertly formatted for ePublication by my friends at Telemachus Press and tricked out with handsome new covers to match the one on The Night and the Music...

Click here to read the rest

Click here to read the rest

Published on February 16, 2012 17:27