Chris Rogers's Blog, page 15

November 15, 2015

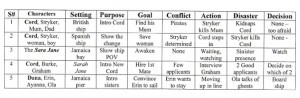

NAKED WRITING: Step Sheets

The longer the book, the more pieces to keep track of. Did I reveal the heroine’s former lover in chapter 6 or 8? What color was that horse?

One of the most useful tools I’ve developed for writing and editing is a simple chart that tracks my scenes. Not only does it provide an index for revisions later, it also helps me visualize the scenes yet to come.

I use a table or spreadsheet with nine columns, assigning a row for each scene. Rarely do I know in advance how every scene will play out. Some writers do. Ridley Pearson (author of the Lou Bolt series) creates all his scenes on 3”x5” cards before starting to write. For me, noodling too much plot detail dilutes my energy for the story.

What works for me is to project my Big Scenes onto separate rows… then I might sketch in a few scenes leading up to and away from the Big Scenes, but mostly I look at the scenes just ahead of wherever I’m writing at the moment.

• Column 1 is where I put the scene number for that row.

• Column 2 is for the characters present in that scene, with the POV character in bold.

• Column 3 is location.

• Column 4 is my purpose for writing that scene. Introduce a character? Show a particular conflict? Insert a clue?

• Column 5 is the POV character’s goal in the scene.

• Column 6 Indicates the conflict.

• Column 7 briefly describes the action that will take place.

• Column 8 indicates the disaster or reversal:

• Column 9 is the decision the character will make in reaction to what happens in the scene.

This decision directs the next Dramatic Unit in the POV character’s goal.

Start with just a few scenes, then build as you go. Or if you reach a sticking point and don’t have a stepsheet, scan your story scenes for the pertinent details and start one. Trust me, this makes writing and editing easier going forward.

November 14, 2015

NAKED WRITING: Your Sagging Middle

You reach the center point of your novel, 25 to 30 thousand words in to the expected word count, and the ideas dry up. It happens to most of us.

What seemed like a full-fledged novel at the beginning feels more like an extra long short-story. You plod along as you try to think of “one more complication” to entangle your characters. How do you stretch the material you’ve imagined for another 30 thousand words?

When I need to prop up a sagging middle, I revisit plot, character, and setting. But first I look at where I can raise the stakes and make the hero’s situation more desperate. Here are four possibilities:

1. Your hero achieves the first goal, only to discover the real goal or problem lies deeper. In Silence of the Lambs, Agent Starling’s interview takes a turn when Hannibal Lecter sends her to Raspail’s car, and she finds a body.

2. Your hero’s actions have an unexpected effect—either positive or negative works. Because Starling showed initiative, her supervisor invites her to help investigate.

3. Unexpected danger strikes close to home. Until now, the killer has taken women at random, but now the senator’s daughter is captured.

4. A supporter might withdraw, turns against the hero or die. Lecter ceases to be available.

In addition to these plot ideas, take a look at your 5 Big Scenes. Could any of these occur at the midpoint? If so, can more complications lead up to and away from it?

Take a fresh look at your hero and the setting. What important information hasn’t yet been thoroughly explored? Say there’s a lake. How does your hero handle water? Love it? Hate it? Fear it?

Death, of course, is one excellent way to inject fresh energy—and it doesn’t have to be literal. It can be the death of a mission, a plan, an idea, a belief. Maybe all these ideas together can give you another 30,000 words.

November 13, 2015

NAKED WRITING: Reversals

Some novelists prefer the screenwriters’ approach to writing scenes, which is slightly different from the Dramatic-Reflective—or Scene-Sequel—process we usually employ. You might want to try it.

A scene is a dramatic unit of time, but for screenwriters it also must occur in the same setting. Every movie scene usually requires an adjustment of cameras and/or lighting.

So a key practice of screenwriters is this: Whatever the situational attitude going into a scene, whether positive or negative, that attitude reverses at the end. Keep in mind that a scene in film often lasts only 30 seconds and rarely more than 7 minutes. So let’s again look at the famous Scarlett-Rhett scene.

It opens with Scarlett rushing down the stairs fearing that Rhett will leave and trying to stop him. After his “I don’t give a damn” line, he walks away, leaving Scarlett at the door crying. Then a close-up shows her saying to herself, “There must be some way to bring him back. I can’t think about this now, I’ll think about it tomorrow.”

So the scene opens with despair but ends with hope.

One famous scene from Jaws starts with Brody bored and argumentative as he throws dead fish into the water to attract a shark that won’t show itself. Then it does. Brody jumps and backs away into the cabin, where Quint is working. Afraid but now convinced, he says, “You’re going to need a bigger boat.”

That scene opens with doubt and ends with conviction.

Try this screenwriter technique and see if it works for you.

November 12, 2015

A Snippet from Here Lies a Wicked Man

“Told you to stay home and finish your breakfast.” Booker fished a granola bar from his jeans pocket, peeled off the foil wrapper, snapped the bar in half and tossed the larger piece for Pup to catch.

The dog gulped down his treat then sat back on his haunches. Ears drooping, he whined comically.

“Give it a rest, you hairy-faced beggar. This piece is mine.” Booker bit the morsel in half and, with his free hand, ruffled the mutt’s fur.

Across the lake, sunlight glinted off a first-story window and reflected off the water. Almost time but not quite. He snapped a few more frames anyway.

After finishing the crunchy breakfast bar, Booker licked his sticky fingers then wiped them down his pants leg. He plucked a small stone from the sodden lake bank and watched the sunlight inch downward toward the pier. When it brightened a brass pelican at the foot of the steps, he lobbed the rock. It splashed through the water’s calm surface, spreading sun-sparkled ripples to lap the shore, adding movement to an otherwise static picture.

The perfect shot. This was the one Booker had set his alarm clock to catch. He triggered the remote—

Then three disasters struck like firecrackers on a string.

Pup barked and streaked toward the lake. In his eagerness to fetch, he sideswiped the tripod.

Booker grabbed for the camera. Mud-mired shoes threw him off balance. He landed on his butt, one knee wrenched painfully toward the rising sun.

The Nikon struck a rock, motor drive whirring like an angry wasp. The crunch of metal and glass made him wince.

“Hellfire, Pup!” He snatched at a clump of weeds to pull himself erect. “When I catch you, I’m going to roast you alive!”

Pup was busy paddling toward the pier, toward the wonderful thing Master had tossed for him to fetch.

The weeds tore loose in Booker’s hand.

Buy It Now Amazon and Kindle.

Death Edge 4

In her 4th Death Edge anthology, Chris Rogers visits a previous investigation team, serves up a new collection of wickedly entertaining characters, and debuts an amusingly devious story by author Chuck Brownman.

Readers who enjoy the darker side of humor, and life on the shadow’s edge, will find this collection wickedly entertaining. For a cleverly crafted read, look no further. You’ll finish this book sorry to see it end.

7 Soul-Shrieking Tales of Suspense

When an old tree dies, it coughs up history—The Grinning Bones

No one understands the walking dead better than a new mom—If Wishes Were Nightmares

A young emissary prepares for the ultimate negotiation—Never Go Home

A mild-mannered man finds courage in a coin—The ESC Choice

Love blossoms on a beach between strange bedfellows—My Parents Were Monsters

Wherever people compete for love, money or recognition, the Death Card may be found buried in the deck—Fury

A city-bred Texas Ranger discovers once again that country towns breed eerie versions of murder—Blood Sisters

Your Free Bonus—sneak a peek at the first chapter in Here Lies a Wicked Man, a Booker Krane mystery.

Buy It Now Amazon and Kindle.

Death Edge 3

In her third deliciously terrifying anthology, Chris Rogers sets loose a crafty bunch of characters – the good, the bad, and the horrible – explicitly for your entertainment. Readers who enjoy exploring the shadows lurking at the edge of ordinary life will be captivated by the wicked humor and evil doings withing these pages. You’ll finish the book hungry for more.

7 Teeth-Chattering Stories of Suspense

A woman new to country life learns that dead things are as natural as living. – Deer Corn

A man murders his neighbor over a pair of prize-winning hogs, and a special prosecutor considers the case a slam dunk. But is it? – Nailed

When super-acute hearing makes even the faintest sounds of human existence absolutely unbearable, where do you go? – Sounds of Silence

Injuries have a way of toughening up a person and teaching how not to be injured again. – Texas Dewberries Don’t Come Easy

A burglary ring outwits the police and successfully evades capture until they cross paths with the Gray Fox Patrol. – Clowning Around

A master passing on his skill and knowledge is as natural as grass, and a serial killer is no exception. – Blades of Starlight Glen

Bullies come in all sizes, and blood-curdling vicious beats “big” any day of the week. – Hammer

BONUS: You’ll find a portion of Chris Rogers’ long awaited cross-genre thriller, Emissary, inside.

Buy It Now Amazon and Kindle.

November 11, 2015

NAKED WRITING: Get Messy

Recently, I read The Representative, a political romantic suspense by Matt Minor. An excellent debut novel, but what I like most is that John David Dothan, freshman representative in the Texas Legislature, leads a messy life.

I quickly become bored with PERFECT story people–perfectly good, perfectly smart, perfectly evil, perfectly spiteful–you get the picture. Most of us in real life are not so carefully chiseled.

Yes, we should draw our characters succinctly, but focal characters, I think, need wiggle-room in their motivations.

When I study a menu, I’m motivated by how hungry I feel, what I want to spend, whether I feel sad and need comfort food, whether I feel like celebrating and deserve a treat and, if I’m dining with others, how much I want to impress them. Seeing my messy front yard, I weigh my guilt at neglecting it with my desire to finish the book I’m writing.

John David Dothan wants to do a great job as State Representative, but he’s plagued by feelings for three women– and he doesn’t want to be the guy who can’t control his passions.

Life gets messy.

In my own debut novel, Bitch Factor, 1998, Dixie’s desire to lock away bad guys conflicts with her desire to spend Christmas with her family. It galled her to know the man who killed Betsy was running free while the family sat with an empty chair at the Christmas table this year.

Dixie’s feelings mess with her decisions—but readers will relate to your heroes more if you show the strong passions that mess with their lives. Equally important, characters with strong passions make us better writers as we decide how they’ll deal with their messy lives.

November 10, 2015

NAKED WRITING: Dramatizing Conflict

I used to cringe when someone said my scene needed more conflict. “Why do characters always have to be arguing or fighting?” Then I realized there are all sorts of conflict. We engage in conflict from the moment we rise each morning with an insistent bladder. That’s urgent conflict, especially if the bathroom’ occupied.

Verbal conflict may be a name-calling battle, or it can be much more subtle and still have impact. It might be two or more characters openly expressing opposing views, or …

• expressing similar views—but the body language or internal talk doesn’t match.

• agreeing on one matter while silently disagreeing on a different matter.

• trying to reach agreement amid auditory, physical or emotional distractions.

Physical conflict might be two or more characters engaged in physical combat, or…

• one person menacing another who won’t retaliate.

• one or more persons engaged in a physical activity while under duress—like climbing a shaky ladder to rescue an animal or digging his own grave.

• a character engaged in a physical activity while another creates distraction.

Situational conflict occurs when your character is faced with…

• a flat tire at 80 miles per hour on the freeway.

• a bomb that must be detonated to save lives.

• a new job with unrelenting demands.

• a new puppy that hasn’t been house trained.

Emotional conflict revolves around a character’s desire or fear and can take place entirely in the mind. Perhaps your character…

• has two options, each equally attractive or devastating.

• has reached a point of no return and must find fortitude to move on.

• is faced with a surprise that turns everything around.

• encounters past lies that negate former beliefs.

When you think about the many possibilities, putting you characters in conflict can be fun.

November 9, 2015

NAKED WRITING: Unforgettable Scenes

The famous “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” scene in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind takes about 2 minutes on the screen or 3 pages in the 884-pg book.

The Shower Scene in Psycho, one of the most famous death scenes in film, lasts about two minutes, from when Marion steps into the shower until the bloody water has drained away. Two minutes on the screen equals about two pages in screenplay jargon. In a film that lasts 2 hours (with credits), it’s quite small.

In the novel, Robert Bloch allotted less than 1-1/2 pages out of 223 to that scene. Imagine how many viewers have watched it since 1960. Rated among the greatest films of all time, Psycho raked in $50 million at the box office then spawned three sequels, a remake, and a TV series.

Imagine—a couple of well-written pages in your story might create the memorable moment that makes it a bestselling novel and a blockbuster film. Every Dramatic Scene conforms to the same simple format: a character wants something, is faced with conflict, and either loses, wins but with problems attached, or loses and gains problems anyway.

Marion wants to take a shower, but a killer wants her dead. She fails to complete her shower and will never take another. That’s pretty final.

Scarlett wants Rhett to stay with her, but Rhett’s had enough of her obsession with Ashley Wilkes. He leaves, and now she has absolutely no one.

The practice of following this simple format—Character with Goal + Conflict = Disaster or Reversal—will guide you from point to point in telling your story and give you the best chance of writing your own unforgettable scene.

November 8, 2015

NAKED WRITING: Cue Your Reader

You’re reading a book… and notice a bit of repeated action or dialogue. or maybe it’s visual—a strange-looking rock or a woman’s red scarf—and you know… it will be important later in the plot.

When “later” comes… you discover you were right. You feel a small.. satisfaction—and a stronger connection to the story.

Clever writers use selective repetition to give a story resonance. It’s a bit like the musical refrain we enjoy in a song.

In a story appearing in Death-Edge 3: 7 Teeth-Chattering Stories of Suspense, a man avoids killing a spider. Instead he scoops the spider up, carries it outside and releases it. That particular characteristic becomes important later in the plot. In Death Edge 2: 7 Bone-Chilling Stories of Suspense—a story titled “Fresh”—a man stabs a woman 26 times. That number is repeated often and proves important at the end.

The stories became reader favorites in the 4-book series, and I used selective repetition in both… though in slightly different ways.

With the spider, a man’s character trait of “do no harm” is first shown by his actions. Then it’s emphasized in dialogue that transpires as his wife teases him. And since the story takes place in the wife’s viewpoint, we know how she feels about his soft-hearted nature. Later we see, hear, and feel other indications of the man’s nature.

Conversely, in the story “Fresh”, the phrase—26 times—is repeated exactly, providing a clue in the murder case. When you want readers to fully understand a selective repetition, use all the senses. When you want it noticed but… not quite understood… employ only one or two senses.

In any case, early in the story is the time to cue your readers to what you want them to notice.