M.V. Clark's Blog, page 2

March 13, 2018

On Reading about Prostitution

The working title of the next novel in The Splits Archive is Zombies in a Brothel and it spent several months being no more than that. This is because my knowledge of sex work was simply too meagre to write anything convincing.

I needed to research commercial sex. So I began by googling reading lists - I found this cracking one from Leeds University. Then I went to the British Library, which is the second largest in the world and holds every book published in the UK and Ireland.

Mind-blowingSitting in the hush of the BL with its high ceilings and rows of leather-topped desks, my mind was completely blown.

I realised that I had only the most basic understanding of sex work, determined by my own anxieties. For example, I’d absorped a famous statistic that around 70% of men visit prostitutes at least once in their life – and promptly suppressed it. That’s just too many men. That could be anyone- Dad, Grandpa, my teacher, the doctor.

As I read I was amazed to discover this figure is completely wrong. More recent research estimates that actually just 6% of men visit a prostitute once in their lives and only 1.5% visiting a prostitute more than once.

That’s much more dealable with. Hysteria be gone!

Also, although I knew that there is more than one kind of sex work, I’d taken a similar mental shortcut to many people. I’d condensed it all down into street-level prostitution and trafficking – very poor, coerced, possibly drug-addicted women controlled by violent pimps.

Now I was reading about the middle class sex-worker in the US. I was reading about Spanish road-side brothels where tired truck drivers stop for the company of other drivers as much as for sex. I was reading about women in rural shacks who cook a meal for their clients, iron their clothes and let them sleep the night.

Similarly, men who buy sex are a very mixed bag. Some just have an excess of sexual energy. Some have a fetish for buying sex. Some are unable to meet women in any other way. Some are stuck in a bad marriage. Some have no time for intimate relationships. Few if any of the reasons on this list signal a happy person living a well-rounded life, but nor do they sound that different from the unhappinesses of men who do not buy sex.

Sex and the SelfHowever, I wasn’t convinced by one of the main feminist defenses of prostitution, - namely that it’s patriarchal to insist that women see their sexuality as an intimate part of their selves.

For me, it’s human for sexuality to be enmeshed with our emotional depths. It’s not a very sexy thought at all, but our consciousnesses are constituted through touch and eye contact when we are babies.

The effect of separating the two is the same for men as for women. The patriarchy might reward women who say their sexuality isn’t part of their essential selves differently from men who say the same. But that’s quite distinct from how it makes men and women feel as human beings.

It’s obvious that some people – women and men - are able to make the separation more easily than others. I accept that the machine-like drive to reproduce has a life of its own. I can see that some people – both women and men – are able to, or even find it quite natural, to meet this need without the involvement of their emotions.

What about love?But the list of reasons why men go to prostitutes makes it clear most of them haven’t detached this need.

When you look at this list, you can’t help realising that even the coldest and creepiest commercial sex is actually about love. More precisely, it’s about love’s absence. Perhaps the odd well-brought-up sociopath can genuinely use prostitutes as a service. But most men invest more whether they’re conscious of it or not.

Take the two motivations that seem to have least to do with love. First, men who see commercial as a practical solution to give them more time for their career. After reading some case studies, it seems these men usually have an underlying depression (unless they are sociopaths, although there is an argument that sociopathy is actually a defense against mental disintegration).

Second, men with a fetish for commercial sex. By definition, they are substituting a thing they don’t really want for something they do. That’s the meaning of a fetish – a substitute for the real thing, which can then absorb your feelings about the thing you really want. Love, in other words.

Two different worlds?Nor do I buy the argument that marriage is just a socially acceptable form of prostitution. But I did begin to see that what happen in commercial sex is not in one universe while what happens in ‘normal’ sex is in another.

There can be tenderness in commercial sex, and there can be exploitation and hurt in ‘gift’ sex.

One prostitute I read about said she felt she was drawing love up out of the earth and sending it into her clients. I expect this is not the full story, but neither is it the full story when people say “I do”.

It was this woman’s words that finally convinced me sex work can illuminate our humanity rather than simply disgrace it. Just as well, seeing as I’m about to write a novel set in a brothel.

March 5, 2018

Oscar Horrors - only queers allowed : Title Fright 12, Oscars Special

Why Rebecca (1940) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991) won Best Picture but Get Out (2017) did not.

Oscar Horrors - only queers allowed.

Why Rebecca (1940) and The Silence of the Lambs (1991) won Best Picture but Get Out (2017) did not.

February 27, 2018

Coming of Rage - Carrie vs Raw : Title Fright 11, Women in Horror Month Special

It's all about the teenagers this week. By the end of the show I'd talked myself out of this being a 'wimmins' episode.

Coming of Rage - Carrie vs Raw

It's all about the teenagers this week. By the end of the show I'd talked myself out of this being a 'wimmins' episode.

February 23, 2018

Guts Reaction - Eyes of My Mother

***SPOILER FREE***

A lot of reviewers have said Eyes of My Mother (2016) has elements of torture porn. Now I HATE torture porn, but I loved this film.

What gives? Well, torture porn has two key aspects - first mutilation of the body, and second, taking pleasure in mutilating the body. I'm not sure Eyes of My Mother really qualifies.

It's set on a remote US farmhouse where a Portuguese immigrant family lives quietly (or are they exiled? They certainly have the wary quality of people who have experienced trauma). The mother is a former surgeon and teaches her daughter to dissect eyes.When their lives are shattered by a violent tragedy, things take a very strange turn and a number of horrific acts are committed, albeit off-screen.

But I don't think the perpetrator takes any pleasure in these acts - she's childlike, almost infantile, she doesn't actually understand what she's doing.

Eyes of My Mother did push me out of my comfort zone - it was so disturbing I had pause it and look up the rest of the plot on Wikipedia to check I wasn't going to regret watching it. That's never happened before.

But I loved the sense of this calcified Portuguese timewarp in the middle of the US, this old, sad energy of an immigrant past that's never really been left behind.

Some reviews say the ending was disappointing, but I thought it was incredible. It conveyed beautifully the inevitability of the lead character's behaviour, like the return of a musical fate motif at the climax of an opera.

Yes, opera. Poetry too. There was all kinds of high art in this horror film. All bad and old and no good, but absolutely stunning.

February 20, 2018

On Being a Clive Barker Virgin

I’ve been saying for a while that if loving horror is an orientation, I’ve only just come out of the closet. I denied myself a lot of wonderful horror writing for years because of this and I’m only now catching up.

First came Shirley Jackson and The Haunting of Hill House, which I've blogged about here.

Then I was preparing for my YouTube show Title Fright 10: Curious Cruelty, which pits Hellraiser against Candyman. I felt I should at least read The Hellbound Heart and The Forbidden, on which they are based respectively. So I opened my first ever Clive Barker book.

Clear, cool and lyrical, with riveting and stunningly relevant plots, they could have been written yesterday, or even in ten years time.

They were also much more frightening than I expected. When I got to that famous line in The Forbidden....

‘I am rumour,’ he sang in her ear. ‘It’s a blessed condition, believe me. To live in people’s dreams; to be whispered at street-corners; but not have to be. Do you understand?’

…it bowled me over. It was as if Candyman was transcending his fictional status by owning it as his chief characteristic. It was as if he had stepped off the page into my reality, and I got a tremor in my gut that is the absolute holy grail of any horror fan.

Good as the film Candyman is, it doesn’t quite manage that.

It’s ridiculous that it’s taken me this long to get into Barker, but I’m seeing my glass as half full - there can’t be many horror fans at my age who can jump in fresh to his oeuvre.

As they say, it’s never as good as the first time.

February 19, 2018

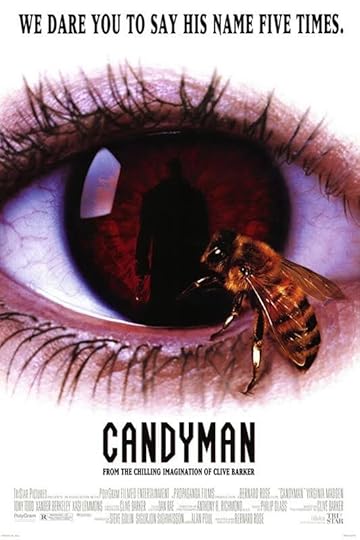

Title Fright - Hellraiser vs Candyman

Clive Barker is a specialist subject and I'm no expert , but these to films are dear to my heart and I had to go there.

Today on Title Fright we’re putting the original Hellraiser (1987) up against the original Candyman (1992).

Hellraiser was directed by Barker himself, and stars Doug Bradley as Pinhead. When a pleasure seeker follows his appetites to their limits, he draws down a punishment that ensnares his entire family.

Candyman was directed by Bernard Rose and stars Tony Todd in the title role. When a curious academic explores urban myths in the ‘hood, she awakens the ghost of a murdered slave.

Just a reminder, this is not a review, it’s a Title Fright. There won’t be plot summaries, and there will be spoilers.

THE WEIGH IN

Let’s compare the films - are they a good match?

Parallel 1 Curiosity.

The engine behind both stories is curiosity. Frank in Hellraiser is desperate to know what lies within the Lemarchand Box – what new realm of pleasure it can reveal to him. Helen in Candyman is obsessed with finding the source of the Candyman legend.

Parallel 2 Portals

In both films, a door is opened to a horrifying supernatural world. It is typically Barkeresque for there to be a magical realm alongside ours full of oddly liberating horrors, whether accessed by opening a box or by urban legend.

Parallel 2 ambiguous villains

Both the Cenobites and Candyman fulfill a morally ambiguous function within the narrative. They are terrifying, sure. The Cenobites are completely pitiless, for example they don’t differentiate between those that call them on purpose and those that call them by mistake. Candyman kills innocent people and steals babies.

But the Cenobites also restore order to the world. They do this by taking Frank – an even greater aberration than they are in some ways - back to their realm.

Similarly, Candyman occupies a kind of moral high ground. He’s a consequence of an even greater aberration than himself - racism. His pursuit of Helen is payback for history.

LET THE FRIGHT BEGIN

Let’s get them in the ring!

Round 1 – Taboo

Hellraiser tackles the taboo of unbounded human desire. This is explicitly sexual in Barker’s original book, The Hellbound Heart, where it’s spelled out that Frank opens the box in search of erotic pleasure. Similarly, Julia helps Frank because she’s sexually infatuated with him.

The taboo that Candyman deals with is race. It’s an incredibly bold and direct foray into the complexities of this issue in modern America.

As an academic ethnographer in a position of white privilege, Helen has been exploiting the culture of poor black people. When Candyman comes to life he doesn’t just haunt her, he frames her as a murderer of black people, turning her whiteness into her biggest problem.

This allows us to confront things that even now, over a quarter of a century after the film was made, are still hard to talk about.

I call this round for Candyman.The taboo of race is far harder to tackle than that around pleasures of the flesh. Additionally, it breaks all sorts of meta-taboos about how race should be portrayed in film – no equating blackness with evil, no interracial relationships, respect white people’s viewing pleasure. It also, incidentally, deals with desire as well. It’s incredibly brave, it doesn’t shrink away from any taboo.

Round 2 – Scale

Hellraiser takes place in a small suburban house and revolves around a single family. It’s very British, very insular, very claustrophobic. Nobody is a victim of circumstance, there’s no broad sweep of history. Just petty venality and benighted personalities. There’s no backstory for any of the characters, except perhaps Frank, but it seems he was born bad.

I’m not minimising Hellraiser. The Cenobites are remarkable and unforgettable – they are the film’s cruel conscience, the cold superego that finally provides a boundary. But Hellraiser’s about horrors that come from within – our own wilder desires.

Candyman, on the other hand plays out on the big expansive social and historical canvas of race in the US. It’s just a bigger film.

I call this round a draw. I don’t think one is better than the other. Hellraiser may be a kitchen sink horror, and Candyman an epic. But both do their thing beautifully.

Round 3 – Translation

Barker wrote and directed Hellraiser. It was based on his own original novel The Hellbound Heart which he wrote intending to turn it into a film. It’s his vision all the way, transferred faithfully from book to screen. This accounts, I think, for its formal elegance – it’s magical in its perfection.

Candyman too is based on Barker’s writing – a short story called The Forbidden, which is set in the housing projects of Liverpool occupied by the white British working class. But it’s been changed. When English director Bernard Rose, who also wrote the screenplay, took it on as a film project, he moved it to the US and made Candyman black.

So it’s a series of translations – from book to screen, from writer to screenwriter, from Liverpool to Chicago, from class to race.

Significantly, a white British director translates the stories of black Americans. During development, Rose went to Cabrini Green, the housing project where Candyman is set. It was by talking to residents that he learned about the derelict apartments, the backless medicine cabinets and the urban myth of Bloody Mary, who kills you after you say her name a number of times.

In his essay The Demon of Racial History, Antonis Balasopoulos says Candyman pulls in two directions – a progressive direction that deconstructs white priviledge and a more reactionary, conservative, racist direction. The progressive element is the way in which Helen’s academic objectivity is revealed to be the real ‘fairy-tale’, a luxury made possible by privilege.

The reactionary aspect is that the social reality of black lives is ‘transcoded’ (this is the Balasopoulos uses, I thought it was interesting because it sounds a bit like translation). It’s transcoded into a more manageable trope for white people, a figure from the bourgeois gothic imagination - a hook-handed monster.

Candyman gains a strange sort of indeterminacy from all this I think, a messiness that is absent from Hellraiser.

I call the translation round another draw. Hellraiser is a note-perfect rendition of one man’s vision, whereas Candyman is a fractured, cacophonic rendition of multiple viewpoints refracted through a very diverse set of minds. Both great in their different ways.

Round 4 - Control

Another way of contrasting the two films is to consider Barker’s ongoing theme of blowing open the door between the real and the imagination, creating a literary microcosm of the ‘further reaches of experience’ he ascribes to the Lemarchand Box.

I was lucky enough to get my hands on Endless Laceration, an essay by Daniel Pietersen which will appear in the forthcoming Thinking Horror: A Journal of Horror Philosophy Volume 2. Pietersen says that Hellraiser ‘reconfigures’ our whole understanding of horror – it’s not a deviation from the norm, it’s a permanent condition with no end. Not unlike the way we are trapped with ourselves.

You could probably get a similar feeling from reading about serial killers, but I know I’d much rather watch Hellraiser, because even if there’s no end to it, it does at least go back inside the box. Barker is in consummate control of the door that he opens and the way we explore the world that lies beyond. It’s an exquisitely composed, perfectly safe journey to a very unsafe place.

Whereas the portal that is blown open by Candyman opens onto such a volatile world - the whole sweep of racial politics in the US. And the film can’t contain it.

This, I think, is why the end of the film – when Helen not only saves the black baby on behalf of the black community, but also becomes a new ‘Candyman’ - is so unsatisfying. As Elizabeth Erwin, writing for Horror Homeroom puts it, “Are we to equate the motivations of Helen, who has been slighted by her husband, with the motivations of Candyman, who has been lynched?”

I call the control round for Hellraiser. Hellraiser takes you to hell, and it brings you back changed, but it does at least bring you back. Candyman dumps you into a much more dynamic and complex hell, and leaves you there, with a sour taste in your mouth and a feeling that the film has lost its way.

IT’S A DRAW!

In Hellraiser, the monsters are inside us. Barker knows exactly what he’s doing and he takes us through a cathartic encounter with them.

In Candyman the horror is much more out of control. The story doesn’t end properly because, in a film so explicitly about racism made by white people, how can it? It’s deeply flawed but rescued by the fact that it literally opens a forbidden box – questions of race and class – in a way that opens up new possibilities for understanding ourselves and our place in the world. Very Barkeresque, at the end of the day.

As to which film is better, I just can’t call it. These are both terrific films and personal favourites of mine. Both the Cenobites and Candyman stay with us. They even exact a kind of affection, because like a lot of horror villains, they embody something true but unspoken that’s liberating to acknowledge.

Can you help me? Can you call it?

Curious Cruelty - Hellraiser vs Candyman : Title Fright 10, Clive Barker Special

Clive Barker is a specialist subject and I'm no expert, but these to films are dear to my heart and I had to go there.

Clive Barker's Sweet Suffering

Clive Barker is a specialist subject and I'm no expert, but these to films are dear to my heart and I had to go there.