Riana Everly's Blog, page 4

December 17, 2021

Some Christmas Magic – A New Book

I’ve been busy these last few weeks, but I’m thrilled to announce I have a new book out, a special story just for Christmas. It is called A Midwinter Night’s Dream, and it is available on Amazon and is free to read on Kindle Unlimited. I have posted about it at Austen Authors this week, but here is what I said.

https://www.austenauthors.net/a-midwinter-nights-dream-a-novel-and-an-excerpt/

When I sat down on November 1st to start my NaNoWriMo project, I never imagined I would have it completed and published within a month and a half. Usually I write quickly but then work slowly, interspersing other projects between each stage of the work-in-progress. But I had decided to write a Christmas story, and I wanted to have it out for lovely readers to enjoy before Christmas.

Oberon, Titania, with fairies dancing

Oberon, Titania, with fairies dancingWilliam Blake, c. 1785

My poor editor looked at me with horror in his eyes when I told him of my plans, but he dropped everything and came through. Rewriting ensued, followed by spell checks, grammar checks, a panicked final proofreading which (I hope) caught any remaining errors, and after a bit of a scramble, the novel is now available for purchase or for reading through KU.

But let me tell you a bit about it. I had so much fun writing my previous release, Much Ado in Meryton, that I thought I would tackle another Shakespeare/Austen combination. While A Midsummer Night’s Dream is not quite my favourite play, I have seen some fabulous performances of it and it brings back lovely memories. And as I thought about the play, and realized that Christmas was around the corner, a plot bunny hopped across the page and inspired me.

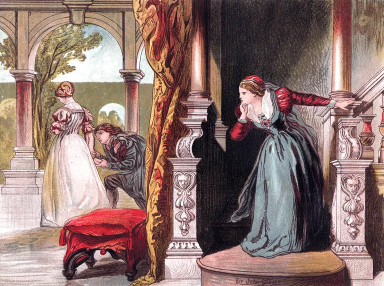

Helena and Demetrius

Helena and DemetriusIn A Midwinter Night’s Dream, the Darcys have been married for over a year and have an infant son. They are looking forward to their first Christmas together at Pemberley, having spent the previous year in London, when suddenly they are stuck with not one, but two houseguests. One of these is Prudence de la Pole, an old friend from Will’s childhood, now a young woman who is bored and is looking to make trouble. The other is Will’s cousin Colonel Richard Fitzwilliam, who is seeking to escape his mother’s matchmaking plans. Richard and Prudence were also friends once, but something happened that turned them against each other.

These are our Hermia and Lysander, Helena and Demetrius. And who steps in to take the part of Oberon with his magic love potion? Why, Mrs. Annesley, of course, with Georgiana as her tentative Puck. She delves deep into the ancient lore of Derbyshire’s mystical past to work her magic, but can she cast the right spell to bring Richard and Prudence together in time for Christmas? Or will her magic go horribly, disastrously wrong?

A Midwinter Night’s Dream is available at Amazon and is free to read on Kindle Unlimited. This link should take you to your country’s store: mybook.to/amidwinternightsdream

Here is an excerpt from A Midwinter Night’s Dream. I hope you enjoy it.

“I hope your sister is pleased. Georgiana was insistent that we not change too much.”

Will chuckled. Until they were married, Elizabeth had hardly heard him laugh at all, so serious was he. But marriage seemed to have eased some of the strictures he placed on himself, and he was, when in the right spirits, almost as quick to smile now as his friend Bingley.

“Georgie hardly remembers our mother, so young was she when she passed. She was concerned more about the idea of the room than the reality of it. From the times I have seen her sitting in here and smiling, I do not think her upset at all. We have a future to look forward to, all of us, and should not dwell in the past. Especially now.” His large hand came down to caress the sleeping baby’s downy head with a tenderness Elizabeth could never have imagined.

“The room is alive again, as is Pemberley, thanks to you.” He sat in silence for a few moments. She rested her head against his side, content in the warmth of his arms and lulled by the soft thrum of his heartbeat. She stifled another yawn. “Let me call Mrs. Cotton,” he echoed Mrs. Reynolds’ suggestion. “You look like you would do well to sleep a spell.”

“Not quite yet, Will. I have still not decided where to put the mistletoe. All of the other greenery will be well displayed on the ledges and the tables, but I cannot think where best to put the mistletoe. It is quite distracting me. Allow me to ponder it for a few minutes more, and then I shall yield up my beautiful burden,” she smiled down at her sleeping son, “and retire to my room for a rest.”

She closed her eyes and imagined the mistletoe, picturing the sprig of small yellowish leaves and waxy white berries. Georgiana had suggested hanging it from the lintel over the main doorway to the hall, but in her mind it looked… wrong. “If we place it there,” she gestured, “you will have to duck every time you enter the room.”

She was rewarded with another low chuckle. “Then I shall have to ensure that I am compensated for my troubles.” He kissed the top of her head again before she turned her face towards him and presented another part of her to kiss.

***

And here is another.

Elizabeth blinked away her sleepy memories and surveyed the scene now before her. Yes, the beautiful snow-bedecked fields still lay pure and white beyond the large window, the baby still slept in her arms, and she was still cuddled against Will’s side as Prudence batted her long lashes in Will’s direction. Will and Prudence might have shared memories of Christmases spent together in childhood, but Elizabeth was the one Will held in his arms; she was the one with his name. Soon Prudence would be gone, and there would be nothing to worry about.

Everything would be fine. She was quite prepared for Prudence’s little quips and comments and would comport herself with the dignity that her station as Mrs. Darcy of Pemberley demanded. There was nothing that could trouble her now.

A footman appeared at the door and caught everyone’s attention with a discreet cough.

“A visitor has arrived,” he announced. “Colonel Richard Fitzwilliam.”

The footman disappeared back into the hall where his duties lay and another figure appeared in his place. This one was a man a little older than Will and not quite as tall, with the same dark hair and enough of a resemblance to mark him as kin.

Will twisted about in his place to face the door, pulling his arm from about Elizabeth’s shoulders and setting the baby to crying once more.

“Richard?”

“Will!” the newcomer boomed. “I do hope you have a room for me, because I have come to spend Christmas!”

To all who celebrate, I wish you a Merry Christmas, and to everyone I wish a wonderful and healthy 2022.

November 19, 2021

Some musings on my new book, and an excerpt

I’m just thrilled at the reviews and feedback I’ve been getting for my new novel, Much Ado in Meryton.

As much fun as it was to write, it is also, in some ways, the hardest book I’ve written. It’s a mash-up of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, and as such I needed to really emphasise the bristly relationship between Lizzy and Darcy, to bring them into line with Beatrice and Benedick.

Come and read what I had to say about it at Austen Authors, and read a couple of excerpts.

https://www.austenauthors.net/a-new-release-and-an-excerpt/

November 3, 2021

Much Ado about Much Ado

I am delighted to announce that my newest romance, Much Ado in Meryton, has been released!

I had so much fun writing this book. As much as I love Jane Austen, I love Shakespeare as well. His wit, inventiveness, and sheer snark are all but unequalled, and I could (and might) devote an entire article to his insults and come-backs. And so, when I first thought about writing a Pride and Prejudice / Much Ado About Nothing mash-up, it was no hardship at all for me to dive right in.

And what fun it was! I had read Shakespeare’s play several years ago, and have seen it performed on stage more recently, but I started my renewed exploration with a viewing of the fabulous 1993 movie. Kenneth Branagh, Emma Thompson, music by Patrick Doyle, that gorgeous Tuscan scenery… how could you go wrong? For all of Branagh’s foibles, he does theatre like this brilliantly, and this movie remains one of my favourites, just for the sheer beauty of it.

I then re-read the play, scribbling notes as I went, and indulged myself with a more modern take on the play, namely the BBC’s version for its ShakespeaRe-Told series from 2005.

This modern interpretation had some work to do, because parts of Shakespeare’s original plot – namely the storylines around Don John and Hero – don’t quite work in the modern world. This version is not perfect, but it did a really good job of recontextualizing elements of the play and it gave me a lot to think about.

Then, after one more read-through of the play and a pile of sticky notes, I started writing.

I know Pride and Prejudice really well and have read it and reread it so many times I feel I have plumbed a lot of its depths (although there is always something new in there, always something that other people discover that makes me say, “oh!”), but I really enjoyed an equally deep dive into the Shakespeare. Who were these people? Why did they react they way they did? What happened before the first scene that set Beatrice and Benedick off on their “merry war of words?” Why was Claudio both so keen to marry a girl he had hardly seen, but equally quick to distrust her even before he had said two words to her?

I do not have all of Shakespeare’s answers to these questions, but I created my own, and then set about adapting them to P&P. As I found with Teaching Eliza and Pygmalion, I was surprised at how well the two storylines fit together. There are clear echoes of Beatrice and Benedick in Lizzy and Darcy’s sparring, but I also discovered more than a thread connecting Jane and Bingley to Hero and Claudio.

Did I succeed? How will it all turn out? You will have to make up your own mind about that!

Much Ado in Meryton is now available in eBook and will soon be available in paperback at your favourite on-line bookseller.

September 27, 2021

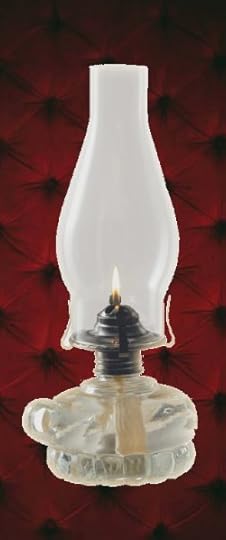

Tech Issues – Regency-Style

After a series of computer woes, I started wondering what tech issues might have plagued our Regency friends. Here is a short story for you.

***

Hunsford, Easter time, 1812

The door slammed behind Fitzwilliam Darcy as he blew into his bedchamber like a gathering storm. Thunder all but followed him into the room, and a frisson not unlike lightning crackled at the edges of his sight. The ewer on his washstand rattled in its place, and the windowpanes shook in their frames.

“Damned impertinent, headstrong girl!” he growled to the draperies. “Thankless, heartless… beautiful Elizabeth.” Fury and pain fought for supremacy in his heart and he collapsed into the large chair by the fire. She had refused him! Refused his offer of marriage! And not kindly either, but with angry words and a torrent of abuse that had rattled the foundation of his being. She ought to be grateful that he had lowered himself so much as to consider her, but instead of words of love and appreciation of his condescension, she had enumerated his every failing and fault, and had in turn accused him of a great many wrongs, some true and some quite mistaken. Did she really believe Wickham? Did she honestly take that man’s word over his own? Could she have so mistaken his good character in favour of the scoundrel’s lies?

The pain of rejection began to fade as the fury grew stronger. He could not let this lie. He must defend himself. He could think of only one way. A letter!

He pulled himself upright and stomped over to the writing desk by the window. His head hurt. His back ached. His throat was as dry as dust. He went to the pitcher to pour himself a glass of water and then sat down to compose his letter.

“Sir?” His valet appeared in the doorway. “May I be of assistance?”

Blast the man. Monroe was an excellent valet, always at hand, and with a fine talent for cravats, but at this moment Darcy wanted nothing more than to be alone. Well, perhaps a cup of coffee would help. He could send Monroe to the kitchens and achieve both aims at once.

He swung around to make his request, but in his agitation his elbow struck the full glass of water, knocking it over and spilling the contents all over the desk. The paper was soaked.

“Allow me, sir.” Monroe was at hand in a moment, but the damage was done. The entire short stack of fine paper was a ruin. It would dry in time, and Aunt Catherine could easily afford more, but he needed paper, and needed it now.

Darcy shoved back from the desk to stand. Something cold trickled down his leg. Blast it again. He had spilled some of the water on his trousers. And these were his good ones too, that he had worn specially to make a good impression on Elizabeth as he offered her more than she ever ought to expect. The cold water ran down his leg and into his boot.

“Coffee. I shall be in the library. I must attend to some correspondence at once.”

“Yes sir.”

Without bothering to change, Darcy stormed through the hallways of the great house. The library was on the far side of the courtyard to the rooms where his aunt was entertaining her guests, that silly parson and his plain and too-sensible wife, with his cousins at her side. They would not hear him here. He could write his rebuttal in peace.

He found a new stack of paper and took it over to the large table. What now? The lamp would not light. His candle would never give sufficient light for what needed to do. He tried the flint again, but the wick would not light. The oil reservoir must be empty. He would ask Monroe to attend to it when he arrived with the coffee. He sighed and picked up the brass lamp.

Was that something inside, blocking the oil from reaching the wick? As he moved, the glass chimney shifted from its collar. Somebody had not secured it properly! Some silly maid, or… oh no! There had been oil in the lantern after all. His sleeves were covered in the viscous and foul-smelling substance, and irrevocably stained as well, he suspected. He groaned and ran a hand through his hair…

Oh blast and damnation. He had oil on his hand as well, and now his hair was a slimy, smelly mess. He groaned. Well, there was nothing to it, but to go on with his task. He could change later.

He managed to light the oil lamp and settled into his chair. That top sheet of paper would have to do as a towel. He wiped his hands on it until they were as clean as he could manage, and then reached for the ink well. There were some quills in the drawer, and a knife, and he set about fixing a pen.

Now he could set his mind to his task. “Be not alarmed, madam,” he wrote, the fury somewhat dampened by the water stains on his trousers and oil on his coat sleeves. He wrote in anger at first, and then with more care and deliberation. He must acquit himself of these baseless accusations, or at least explain his actions. Could Jane Bennet really care for his friend Bingley? Had he been wrong? Unthinkable… and yet…

He completed his first draft. There, in black and white, he laid out his every dealing with that cur Wickham, and even divulged the sorry story of his sister’s involvement with that accursed man. Surely Elizabeth must believe him now. The anger had faded and become resignation and fatigue. He would find a way to get the letter into her hands. But first he must write out a good copy. This one, covered in notes and crossed out words and phrases, the letters so rushed as to be almost illegible, would never do.

He reached for more paper.

“Your coffee, sir.” Monroe stood at the door with a silver tray in his hands.

“Yes, put it on the table. I shall manage.” The valet did as requested and disappeared into the dark hallways. Darcy stood and massaged the back of his neck, which had grown stiff as he wrote. What…? Oh blast. More oil, now on his neck and his cravat. He should just remove his neckcloth, but he was a gentleman, the grandson of an earl, and could never be seen in such deshabille outside of his personal rooms. He would wash later.

He poured his coffee and raised the delicate china up to his lips.

“I forgot to say, sir, your cousin is looking for you.”

Monroe appeared from nowhere. Caught unaware, Darcy’s hand jerked and coffee sloshed over the side of the cup and down the cravat he still wore. He let out another groan, unsure whether he was more upset about the new stain or the loss of the precious black liquid. His eyes fluttered closed and he sighed.

At last, somewhat fortified with the remainder of the coffee, he returned to the desk to write out a good copy of his letter. His pen was quite worn down, and he must repair it before attempting to write anything he would show to another. He found the knife again and set to work.

“There you are, Will. Aunt Catherine has been all in a bother wondering where you were and why you did not appear at dinner.”

The knife slipped, stabbing into his thumb. He let out a yelp.

“Damn you, Richard!” Of all the moments for his cousin to appear, why this one?

“Good God, Darce, you’re bleeding. It looks bad.”

Darcy looked down at his thumb. Richard was right. This was not small nick, but a rather serious cut. He stared at the welling blood, his mind quite unable to determine what to do about it.

In a moment Richard was at his side. “Here, your handkerchief. Let me wrap it for you.” Yes, as a military man, Richard knew how to deal with minor wounds. He took Darcy’s handkerchief from his pocket and tore off a strip, which he wrapped around the bleeding digit. “That should hold. I’ll find Monroe and call for some bandages.”

“No, please do not. This will suffice. I must finish this letter in peace.”

His cousin’s eyebrows rose.

“It is… That is… Never mind. Just leave me in peace.”

“If you wish. But do look after that thumb, Darcy. The blood is seeping through the cloth already.’

Darcy sighed again and wiped his forehead. “Very well.”

He managed to repair the pen and then went to refill the empty ink well with his still greasy fingers, just as a spark from his still-burning candle touched the oily paper he had pushed aside.

~~~

Several hours later, Elizabeth Bennet was walking through the paths by Rosings when a figure approached her from a grove, holding out something in his hand that looked like a letter.

“Mr. Darcy!”

Her voice must have betrayed her shock. Never had she seen him like this. Gone was the perfectly attired, assured, and arrogant man. This creature who stood before her was almost pathetic. His trousers had a water stain that dripped all down one leg (not that a lady ever looked at a gentleman’s legs, ever), and his coat sleeves seemed dark at the cuffs. Was he wearing the same clothing as the previous evening, when he had so insulted her with his pathetic proposal? Had he not slept? It seemed not. His eyes were heavy and shadowed, and the shadow of an unshaved beard traced his jaw. There was something on his cravat – was it coffee? – and smudges of blood and grease decorated his brow. But the large ink stains on his shirt cuffs and collar, the burned fabric of his waistcoat, and the soot marks down his cheeks, were the most remarkable of all these imperfections. What on earth had happened? For a moment, she felt a twinge of… sympathy?

“I have been walking in the grove some time in the hope of meeting you. Will you do me the honour of reading that letter?” His voice, usually so haughty and refined, shook, and she wondered if he were fit enough to stand.

She took the letter out of instinct, but then stopped. “Are you well, sir?”

He wavered in place. “I am…” he stumbled.

Elizabeth reached out an arm to catch him before he lost his balance, and the letter fell from her hand. A gust of wind caught the envelope and blew it away in the direction of the stream, where it sank into the bubbling waters.

“Oh no!” Now she was alarmed. Mr. Darcy had gone white. Was he going to swoon?

“Come and sit, sir. And while we are seated, perhaps you can tell me what was in that note that you seemed to have to great trouble to write to me. I promise I shall listen with all attention.”

She held onto his hand as she led him to the bench a short distance away. Was that the trace of a smile on his ragged face? A glimpse of hope in his eyes? Perhaps he had something to say that she ought to hear, after all.

You can also read this story on Austen Authors: https://www.austenauthors.net/technical-issues-regency-style/

August 29, 2021

Literature and Discovery – L’Anse aux Meadows

We were recently in Newfoundland on holiday, and we decided to make the grand trek up the Great Northern Peninsula to L’Anse aux Meadows. Here, at the end of the known world (well, it felt like it), where the road ends and the ocean begins, is a remarkable site: the only known Viking settlement in North America.

A recreation of the large house at L’Anse aux Meadows

A recreation of the large house at L’Anse aux MeadowsPhoto by Riana Everly

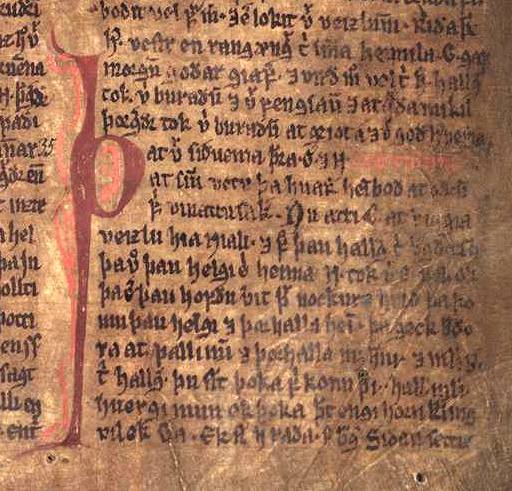

The tale behind the discovery of this site is almost as remarkable as the settlement itself. It began not with an artifact, but with a story. Much like Heinrich Schliemann, who believed the text of the Iliad was more than pure myth, the discovers of this amazing site found fact in the old Norse sagas. These tales, the Vinland Sagas, told of the voyages of Leif Erikson and his crew, who sailed west from Greenland in search of timber and wealth.

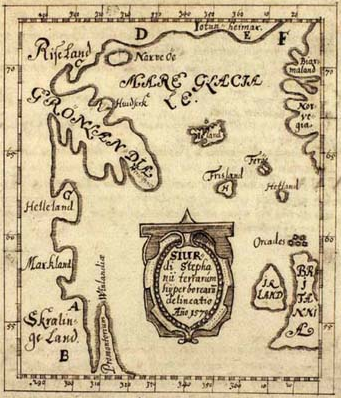

The Vinland Sagas are really two independent Icelandic texts dating from the early 13th century, with different accounts of Norse voyages to Vinland some 200 years before. After establishing colonies in Greenland, these explorers cast their eyes further west, where they discovered more untamed land. Furthest to the north was Helluland, across the Davis Strait from Greenland (possibly Baffin Island). Further south was Markland (generally considered to be Labrador), rich with the trees that Greenland so sorely lacked. And then, south of that and far more hospitable, was Vinland.

Latinized map from c. 1590 showing locations from the sagas

Latinized map from c. 1590 showing locations from the sagasFrom The Saga of the Greenlanders

From Chapter 1

They sailed for another two days before sighting land once again. They asked Bjarni whether he now thought this to be Greenland. He said he thought this no more likely to be Greenland than the previous land — ‘since there are said to be very large glaciers in Greenland’.

They soon approached the land and saw that it was flat and wooded. The wind died and the crew members said they thought it advisable to put ashore, but Bjarni was against it. They claimed they needed both timber and water.

From Chapter 3

There was now much talk about voyages of discovery. Leif, the son of Erik the Red, of Brattahlid, went to Bjarne Herjulfson, and bought the ship of him, and engaged men for it, so that there were thirty-five men in all… Now prepared they their ship, and sailed out into the sea when they were ready, and then found that land first which Bjarne had found last. There sailed they to the land, and cast anchor, and put off boats, and went ashore, and saw there no grass. Great icebergs were over all up the country, but like a plain of flat stones was all from the sea to the mountains, and it appeared to them that this land had no good qualities. Then said Leif, “We have not done like Bjarne about this land, that we have not been upon it; now will I give the land a name, and call it Helluland.” Then went they on board, and after that sailed out to sea, and found another land; they sailed again to the land, and cast anchor, then put off boats and went on shore. This land was flat, and covered with wood, and white sands were far around where they went, and the shore was low. Then said Leif, “This land shall be named after its qualities, and called Markland (woodland.)” They then immediately returned to the ship. Now sailed they thence into the open sea, with a northeast wind, and were two days at sea before they saw land, and they sailed thither and came to an island which lay to the eastward of the land, and went up there, and looked round them in good weather, and observed that there was dew upon the grass; and it so happened that they touched the dew with their hands, and raised the fingers to the mouth, and they thought that they had never before tasted anything so sweet.

From Eirik the Red’s Saga

From Chapter 4

Leif set sail as soon as he was ready. He was tossed about a long time out at sea, and lighted upon lands of which before he had no expectation. There were fields of wild wheat, and the vine-tree in full growth. There were also the trees which were called maples; and they gathered of all this certain tokens; some trunks so large that they were used in house-building.

From Chapter 9

Karlsefni proceeded southwards along the land, with Snorri and Bjarni and the rest of the company. They journeyed a long while, and until they arrived at a river, which came down from the land and fell into a lake, and so on to the sea. There were large islands off the mouth of the river, and they could not come into the river except at high flood-tide. Karlsefni and his people sailed to the mouth of the river, and called the land Hop. There they found fields of wild wheat wherever there were low grounds; and the vine in all places were there was rough rising ground. Every rivulet there was full of fish. They made holes where the land and water joined and where the tide went highest; and when it ebbed they found halibut in the holes. There was great plenty of wild animals of every form in the wood.

But these are stories, legends, fiction, are they not? Researchers Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine Ingstad thought not. There were sufficient details in the sagas, references to plants and animals and geographic formations to lead the Ingstads to focus on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland as the probable site of the settlement. They surveyed the territory and began asking around: Did anybody know of some unusual land formations in the area, something that probably wasn’t formed by Mother Nature.

The remains of a house at L’Anse aux Meadows, recovered in sod after excavations were complete

The remains of a house at L’Anse aux Meadows, recovered in sod after excavations were completeIn 1960 someone had something to tell them. George Decker, a resident of the small fishing village L’Anse aux Meadows led them to an area the locals called the “old Indian camp,” where children played among the low regular mounds, just a few inches high but still distinct. To an archeologist’s eye, these grass-covered shapes weren’t just mounds in the earth, but the remains of houses.

Archaeological excavations began the next year. From 1961 to 1968 they carried out seven excavations of the remains of eight buildings. The excavations showed that the houses were originally made of sod that rested on a frame, the same construction found in Iceland and Greenland at the time of the settlement, about 1000CE. Other evidence was collected as well. In the baking pit of one house they found an oil lamp and a spindle wheel; in another a fragment of a bone needle for knitting, and in another a bronze pin with a ring-shaped head that the Norse used to pin their coats. There was also slag from smelting and forging iron, as well as the iron nails and rivets used in boat building. This was ample evidence to assert that this had been a Scandinavian settlement.

Norwegians Land in Iceland in 872, by Oscar Wergeland, 1877

Norwegians Land in Iceland in 872, by Oscar Wergeland, 1877As a writer, this real-life story really resonated. The sagas are literature, to be sure, but history as well. The fanciful stories held more than a thread of truth, and open-eyed scholars chose to approach them as real accounts, leading to a wonderful discovery. Although, as historical fiction authors, we do not seek to record historical events for their own ends, this is perhaps a lesson that we can bring the past to life. Perhaps when we do our research and make it sing in our stories, we can shine a little light on a little piece of the past that will let the explorers and archeologists forge their own paths and find even more things that we had never imagined.

And so here is to the sagas, here is to the Vikings, and here is to the Ingstads and everyone who searched for truth in literature. Raise a cup of mead with me, and perhaps a glass of good sweet Vinland wine.

The excerpts from the sagas were taken from the following translations:

The Saga of the Greenlanders, from The Norse Discovery of America, Arthur Middleton Reeves, 1906

Eirik the Red’s Saga, Rev. John Sephton, 1880

August 27, 2021

Austen Authors – Travels and a Cover Reveal

We have been away on an actual holiday, and I have a new book on the horizon. Read my post at Austen Authors for all the news, including a cover reveal for Much Ado in Meryton, coming soon!

https://www.austenauthors.net/recent-travels-and-a-cover-reveal/

Western Brook Pond, Gros Morne

Western Brook Pond, Gros Morne Green Point, Gros Morne

Green Point, Gros Morne Recreated sod house at L’Anse aux Meadows

Recreated sod house at L’Anse aux Meadows Sunset at Twillingate

Sunset at Twillingate Ferryland

Ferryland Excavations at the Colony of Avalon

Excavations at the Colony of Avalon Twillingate harbour

Twillingate harbour St. John’s

St. John’s

August 4, 2021

Ye Gods! Austen in August

I’m delighted to be part of this year’s Austen in August. This is a month of guest posts, roundtable conversations, give-aways, and all things fun and Austenesque at The Book Rat. I decided to pen a short story for readers to enjoy. It’s a bit – or a lot – silly, and hopefully a lot of fun.

Please click on over to read all about Lizzy, Darcy, and a couple of wayward Ancient Greek gods. There’s a give-away too.

http://www.thebookrat.com/2021/08/ye-gods-short-story-giveaway-from-riana-everly.html

July 30, 2021

Shakespeare and Austen

Today is my day to post at Austen Authors. I have a new novel in the works, a mash-up of Pride and Prejudice and Much Ado About Nothing, and it seemed natural to take a look at what Austen herself thought of the Bard.

You can read the original post here:

https://www.austenauthors.net/shakespeare-and-austen/

And I’ll post the text here:

Shakespeare and AustenIf you were asked to name two famous English writers, chances are pretty good that the list would include William Shakespeare or Jane Austen – or possibly both! They lived two centuries apart, but their fame and influence has been long-lasting and global. Austen herself grew up during an age when Shakespeare’s work was established in the repertoire of the day, but also when his work was coming under scrutiny, and she addresses these issues in her writing.

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, and over his lifetime he wrote at least 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and a handful of other poems and works. I won’t discuss the various theories about the true author of these works here. They are interesting, but for Jane Austen, at least, there was no question that Shakespeare was Shakespeare.

Shakespeare was successful as a playwright and actor during his lifetime, but was considered as just one of a number of talented writers of his age. His true fame was to come about a century after his death. Indeed, during his lifetime he published his sonnets but not his plays. They were intended for performance, not for posterity, and his troupe took pains to keep the scripts out of the hands of rival acting companies. Even then, piracy was a problem for authors!

During the years between his death in 1616 and Austen’s lifetime, his reputation grew. By the end of the seventeenth century he was acknowledged as a brilliant writer, and while his style fell in and out of favour, his works were popular on the English stage. His true meteoric rise, however, came after the Licensing Act of 1737. This Act of Parliament required that all new plays be approved and licensed by the Examiner of Plays, who assisted the Lord Chamberlain. The purpose was simple: to control and censor what was being said about the government on stage, for parodies and satire were scathing and very popular. Since this act applied only to new plays intended for public performance, a return to older works was always safe. Consequently, in the second half of the eighteenth century, a quarter of the plays performed in London were by Shakespeare.

But Shakespeare’s reputation wasn’t entirely golden. Even as his fame rose, so did the voices of the critics. Performance scripts often deviated from the folio edition (or editions, for there is no urtext of the plays) and endings were sometimes changed to better suit the sensibilities of the times. More importantly, the puns and double entendres that bring such life to the plays were looked down upon and some editions expunged them from the texts, although by the late 18th century they were mostly back. The only holdout of note was Thomas Bowdler, whose reworkings of the plays deserves another post at another time.

By the time Jane Austen was writing her own great works, there was a bit of a split between the Shakespeare of bawdy plays and the Shakespeare of refined high poetry. Austen herself references this in Mansfield Park, when the Bertrams and their friends start planning their own theatricals.

Henry Crawford sets out the popular notion of Shakespeare, the man of the stage.

“I once saw Henry the 8th acted, —-Or I have heard of it from someone who did—I am not certain which. But Shakespeare one gets acquainted with without knowing how. It is part of an Englishman’s constitution.”

Edmund, on the other hand, presents the scholarly side of things.

“No doubt, one is familiar with Shakespeare to a degree,” said Edmund, “from one’s earliest years. His celebrated passages are quoted by every body, they are in half the books we open and we all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions…”

Emma Woodhouse would probably gravitate more to Henry Crawford’s take on the Bard, as someone everyone has heard of without really studying his works. She explains to her friend Harriet that,

“When Miss Smiths and Mr. Eltons get acquainted—they do indeed—and really it is strange; it is out of the common course that what is so evidently, so palpably desirable—what courts the pre-arrangement of other people, should so immediately shape itself into the proper form. You and Mr. Elton are by situation called together; you belong to one another by every circumstance of your respective homes. Your marrying will be equal to the match at Randalls. There does seem to be a something in the air of Hartfield which gives love exactly the right direction, and sends it into the very channel where it ought to flow.

The course of true love never did run smooth—

A Hartfield edition of Shakespeare would have a long note on that passage.”

In Sense and Sensibility, the Dashwoods are devotees of Shakespeare and his plays, because it appears they were reading Hamlet together, as is seen in this passage.

It was several days before Willoughby’s name was mentioned before Marianne by any of her family; Sir John and Mrs. Jennings, indeed, were not so nice; their witticisms added pain to many a painful hour;—but one evening, Mrs. Dashwood, accidentally taking up a volume of Shakespeare, exclaimed,

“We have never finished Hamlet, Marianne; our dear Willoughby went away before we could get through it. We will put it by, that when he comes again…But it may be months, perhaps, before that happens.”

“Months!” cried Marianne, with strong surprise. “No—nor many weeks.”

And as for Catherine Morland from Northanger Abbey, her transformation from unassuming tomboy to a heroine worthy of adventure was guided in part by Shakespeare.

And from Shakespeare she gained a great store of information—amongst the rest, that—

“Trifles light as air,

“Are, to the jealous, confirmation strong,

“As proofs of Holy Writ.”

That

“The poor beetle, which we tread upon,

“In corporal sufferance feels a pang as great

“As when a giant dies.”

And that a young woman in love always looks—

“like Patience on a monument

“Smiling at Grief.”

Scholars have also spent a great deal of time finding Shakespearean influences in Austen’s works. In the 1870s, critic Richard Simpson likened Persuasion to Twelfth Night, particularly the passage where Anne Elliot talks to Captain Harville about women’s constancy. “Miss Austen,” he wrote, “must surely have had Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night in mind while she was writing this novel.”

Contemporary scholar Nina Auerbach sees influences of Hamlet in Mansfield Park, both of which pivot around the aborted performance of a play within a play, and she likens Fanny to Hamlet himself, both disgusted with what they see but reluctant to act. And Roger Gard compares the conversation between Fanny and John Dashwood at the beginning of Sense and Sensibility to King Lear’s daughters, who plot to strip their father of all his comforts. Others have likened Emma to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with all the misguided matchmaking, and Pride and Prejudice to Much Ado About Nothing.

It is the last of these that intrigues me because my current work-in-progress is exactly this: A mashup of these two great works. The bickering between Beatrice and Benedick maps so beautifully onto the antagonism between Elizabeth and Darcy, it was a book crying to be written. I am not the first to attempt this by any means, and nor shall I be the last, but I had a great deal of fun as I explored the texts to write my version.

Here is an excerpt from my story, with the provisional title of Much Ado in Meryton. I hope to have it ready for publication by September 2021.

***

On one particular evening towards the end of October, they were all gathered in Mrs. Robinson’s parlour for an evening’s amusement at cards and games. The Robinsons were a family of comfortable if not excessive means, their lands bordering upon those of Netherfield. Mr. Robinson had offered his assistance in any matters which Bingley required, and hoped to be a good neighbour to the newcomer. It was therefore to Mr. Bingley’s advantage, as well as personal satisfaction, to befriend the man and his family, and he was present at every event held in that house.

Elizabeth and Charlotte were sitting on the settee with Miss Margaret Robinson, talking about some diverting if quite inconsequential matter, when Mr. Bingley and his party arrived. All rose and a series of bows and curtseys ensued, with one remarkable exception. Mr. Darcy most definitely did not offer any manner of salutation to Elizabeth. He bowed to Charlotte and muttered appropriate words to Miss Margaret, and quite ignored her very existence. It was the Cut Direct if ever she had seen one. She gaped after him as he walked on.

“I was correct, it seems,” she observed for any ears that happened to be near, “when I presumed Mr. Darcy to be no gentleman.”

To which, Mr. Darcy surprised her by turning to speak directly to her for the first time since the night of the assembly. “How fortunate then, Miss Bennet, that you are no lady to care.” He turned his back and began to move into the room.

“How happy that his purse is full then, for the man himself is an empty pocket.”

He turned once more and glared at her. “How happy that we are so distant from Egypt, lady, for your tongue is more venomous than all the asps in the Nile.”

“Darcy!” Mr. Bingley was at his side in a trice. “What are you doing? This is most unlike you. I know you have a hot temper at times, but I have never heard you speak to a lady like this. You were the one who told me always to take the higher path. What is this? Come away at once.”

Darcy sniffed and stuck his nose up into the air and walked away without another word, Bingley hissing into his ear. That man’s back was his best side, to be sure!

“Lizzy?” Charlotte’s voice was concerned. She waited until the two men had passed beyond hearing. “Is it wise to make an enemy of such a man as this? I have long known you to be impertinent, but never cutting. You were quite cruel. Has he injured you so gravely?”

Elizabeth sighed. “There is something about him that turns me into a termagant. His every word is like a cat clawing at my legs, calculated to annoy and cause grief. And I am not the only one in Meryton who seems to dislike him. I do not believe he has uttered two friendly words to anybody in the neighbourhood since he arrived, save Mr. Bingley and his sisters. And Mr. Bingley is so open and friendly a man. I wonder that they should be friends at all, they are so very different.

Charlotte clucked her tongue. “That they are! Two more different men it is hard to imagine. Mr. Bingley is so determined to like everybody that he, in turn, is sure of being liked wherever he appears. Whereas Mr. Darcy is so determined to be dissatisfied with everything and everyone that he continually gives offence. They are a strange pair indeed.”

“Just as we are, Charlotte,” Elizabeth laughed.

July 7, 2021

Butter Tarts: A Sweet Bite of Canadian History

Last week was Canada Day, and as a foodie with a sweet tooth, I celebrated by making butter tarts. But I’m also a history geek, so a recipe wasn’t enough for me. I needed to know where these little morsels of sugary delight came from. And so, down the rabbit hole went I, and this is what I found.

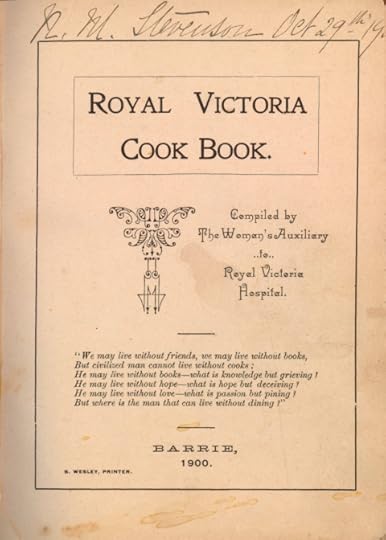

The front page of

The front page of The Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital Cookbook

Butter tarts, for the uninitiated, are a quintessentially Canadian pastry, similar to pecan pie without the pecans. They are small pastries with a single short crust and a slightly runny sugary filling that is crunchy on top from the baked sugar. Some have raisins, some do not. This seems to be a greater national divide than English/French. However, both sides seem willing to talk out their differences over coffee.

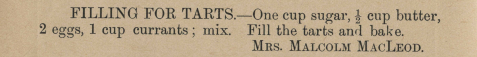

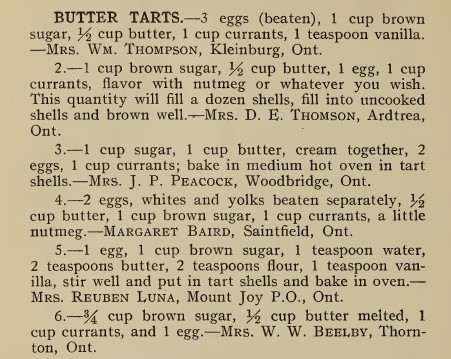

The first recorded recipe for butter tarts is found in The Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital Cookbook from Barrie, Ontario, published in 1900. This recipe, like so many from its day, is more description than direction.

“One cup sugar, ½ cup butter, 2 eggs, one cup currants; mix. Fill the tarts and bake.”

From page 88 of The Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital Cookbook (Barrie, 1900)

From page 88 of The Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital Cookbook (Barrie, 1900)The woman who provided this recipe, Mrs. Malcolm MacLeod, presumed the baker knew how to make the tart shells and how long to bake them, a reasonable enough assumption for the times. The Medieval recipes I have don’t give anything close to precise directions. “Cook till done” seems to be about as exact as they get.

From p.240 of the Canadian Farm Cook Book (Toronto, 1911)

From p.240 of the Canadian Farm Cook Book (Toronto, 1911)Versions of butter tarts were printed in newspapers over the next decade and the recipe was included in the Canadian Farm Cook Book from 1911. In this volume, these treats are actually called butter tarts (unlike the generic “filling for tarts” from 1900) and there are 6 versions of the recipe, contributed by women from across Ontario. Either this dessert had become very popular over the preceding decade, or else the recipe was out there in world, just waiting for Mrs. MacLeod to submit her version for the Royal Victoria Hospital’s book. My guess is the former, and this is why.

Although we don’t see a published recipe until 1900, the story of these treats goes back a lot further. It is thought that butter tarts saw their origin in the mid 1600s with the filles du roi. These “daughters of the king” were a group of about 800 young unmarried French women who were actively recruited and whose immigration to the New World was sponsored by Louis XIV between 1663 and 1673. This program was designed to strengthen the colony of New France by encouraging marriage, family formation, and the birth of lots of French children on North American soil.

These women, as one might imagine, were resourceful people. They brought with them their traditional French recipes, but had to adapt them to whatever was available in their new home. Sugar pie (tarte au sucre) might have been one of these recipes, with a filling including sugar (often including maple syrup), flour, butter, salt, vanilla, and cream. If you want to try these, here’s a recipe that looks nice and simple: https://www.recettes.qc.ca/recettes/recette/tarte-au-sucre-193810 Time and experience, and a possible lack of some of these rich ingredients, transformed this French and Quebecois dessert into the butter tarts I’ve been playing with.

Arrivée des filles du Roy à Québec, reçues par Jean Talon et Mgr Laval, vue par Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale (1872-1845).

Arrivée des filles du Roy à Québec, reçues par Jean Talon et Mgr Laval, vue par Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale (1872-1845).I have a work-in-progress, a completed draft in need of a good edit or five, that takes place in Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in 1815. At one point in the story, my main character brings some treats to a friend. Perhaps I’ll let her bring some butter tarts. It certainly seems like the right pastry at the right time.

For my own experiments, I tried a few recipes. Butter tarts are supposed to be a bit runny, but I like mine of the firmer side. I ended up liking a recipe from the New York Times, but I tweaked it a bit to my tastes, because that’s what I do! I found the ratio of pastry to filling too high, and rather than cutting down the amount of pastry, I doubled the filling. I also played with some of the proportions of ingredients.

My creation

My creationHere’s what I ended up with. This recipe has a lower proportion of butter and egg to the sugar, and far fewer raisins or currants. See if you prefer this or Mrs. MacLeod’s version from 1900.

RECIPE

Butter Tarts

Makes 12 tarts

Ingredients

For the pastry

1 ½ cups flour (191g)Pinch of salt½ cup cold butter¼ cup ice water1 egg yolk1 tsp white vinegarFor the Filling (this is doubled from the original recipe to make a deeper tart)

¼ cup raisins (optional)2 cups packed brown sugar½ tsp fine sea salt½ cup soft butter2 tsp vanilla extract2 large eggsInstructions

Make the pastry in the normal manner, adding water till the consistency is right. Chill in the fridge. Roll out and cut into 12 disks. Press into muffin tins. Chill till ready to use.If including raisins: Cover the raisins in hot water to plump until ready to use. Then drain.In a bowl, combine the sugar and salt, then beat in the butter by hand. Add the vanilla and egg and mix well till combined. Don’t use an electric mixer or you’ll get too much air in the mixture.Add a few raisins to each pie shell. Spoon equal amounts of the filling over the raisins, so each shell is about half full.Preheat oven to 425F and bake for 15-20 minutes, depending on how firm you want the filling. Longer baking time yields a firmer filling. Loosen the tarts from the muffin tin. Let cool a bit.July 3, 2021

Sally Lunn Buns

It was my week to post at Austen Authors, and I decided to explore some of the culinary delights of Regency Bath. Check out my post there to see what I thought about Sally Lunn Buns.

https://www.austenauthors.net/sally-lunn-buns-a-bath-treat/